Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

T

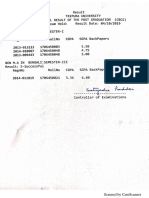

Hochgeladen von

Rahul Kumar SenCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

T

Hochgeladen von

Rahul Kumar SenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

A ‘FRAIL MEMORIAL’ OF AN ‘ARTLESS TALE’ BY AN ‘UNLETTER’D

MUSE’ FOR THE ‘UNHONOUR’D DEAD’: A READING OF GRAY’S

"ELEGY WRITTEN IN A COUNTRY CHURCHYARD"

Jayanta Banerjee (M.Phil.)

Ph.D Scholar,

Department of English

West Bengal State University, Barasat

West Bengal

&

Guest Lecturer

Sri Ramkrishna Sarada Vidya Mahapitha Hooghly

West Bengal, India

Abstract

In this paper, I want to read Elegy Written in the Country Church-Yard (1751) as

a help guide for the students who are in the beginning phase of their course of

English literature. As we see, this elegy of Gray, usually, is included in the Under

Graduate syllabi of Universities. Grays’ Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard

has a special reservation for students of English literature for more than one

important reasons. Primarily, beginning from the Anglo-Saxon Age, it is one the

most sorted elegies in the whole English literature. Secondarily, Gray’s Elegy is

given as a sample specimen to acquaint the students with the Age of Transition,

an age that succeeds the Age of Neo-Classicism and precedes the great Age of

Romanticism. And again, this Elegy of Gray, is read as an elegy for the people, of

the people and by the people because this elegy blurs the generic convention of

the term ‘elegy’ which had previously been a tool to commemorate the ‘hall of

fame’. In addition, this ‘Elegy’ has controversies regarding its date of

composition and occasion as well. Even Gray’s ‘Elegy’ has been the locus of the

New Critics like Cleanth Brooks who discussed the structural elements of it

beautifully. So, in this paper, I have tried to read Gray’s Elegy Written in a

Country Church-Yard under all the aforesaid rubrics giving special focus on its

quality to celebrate the standpoint of the ‘rude forefather’.

Key words: Elegy, Transitional Poem, Nature, Democratic Sentiment, Transience

of life, Immortality, Common Man, Subalternity, Historiography.

General Introduction to Elegy:

Greco-Roman in origin, transplanted into modern European terminology, an elegy was used to

refer to any poem composed in elegiac distich (a couplet alternating dactylic hexameter and

pentameter). At that time elegy was a type of metre not a type of form. Different subjects like

death, love, war – were dealt with in elegies. This was also employed for epitaphs. From the

English Renaissance period, ‘elegy’ or ‘elegie’ has typically been used to a type of reflective

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

639

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

poem that registers a lamentation of the elegist over the loss of someone or something. The

English people liberated ‘elegy’ from being a type of metre and gave it a status of a type of

poem, a genre. There are few overlapping inexplicit cousin terms of elegy, like – complaint,

dirge, lament, monody and threnody which only made the elegy a type of poetry more specific

and definite as a genre. As for its accepted definitions, the strictest one came from S.T. Coleridge

who departicularized the definition by disconnecting elegy from its occasion of any particular

death. He said, ‘elegy is the form of poetry natural to the reflective mind.’ There are literary

masters who opine, loosely, that an elegy is a brief lyric of mourning, a direct utterance of

personal bereavement and sorrow and its basis is absolute sincerity of emotion and expression.

From the so-called Anglo-Saxon Period to the modern times, we find as the most essential

quality of an elegy is its mournfulness. The Greek word elegos means song of mourning. Most

often in a philosophical and speculative way. An elegy is then a lamentation through

introspection and reflection. Nature mostly plays a vital role. Sometime as background,

sometime as foreground, nature is shown to show either sympathy (empathy) to the general

drama of loss and pain of the elegist. In the Anglo-Saxon era, the two great poems – The Seafare

and The Wanderer with the powerful description of nature showed the resigned melancholy of

the Old English people. Later, we see a spasmodic outpouring of sublime sorrow throughout the

centuries. Thomas Gray’s Elegy , alongwith Milton’s Lycidas (1637) mourning the death of

Edward King, Shelley’s Adonais (1821) on John Keats, Tennyson’s ‘In Memorium’ (1833-50) on

the death of Arthur Henry Hallam and Arnold’s Thyrsis (1867) on Arthur Hugh Clough – are

few of the all times’ famous elegies in English literature. All of the five elegies save Gray’s one

are commemorations over their (famous) friends. It is in the elegy of Gray, we come across death

of a common man as the central issue. Usually the elegist praises the virtues of his friend and

often focuses on the evanescent nature of our glorious deed on earth and on how fate plays an

uncertain role in an uncertain world. Elegies end, usually finding solace in divine calculation of

human action and resigning to the divine justice, however bitter the justice may initially seem to

embrace. Then, the elegist always makes a common profit with the readers by unburdening a

personal loss through the psychological process of re-creation.

PUBLICATION, OCCASION AND EDITION:

Readers of Gray’s Elegy always confront with few controversies integral to the editions and

emendations of the text. It still haunts the literary persons that what and why had the poem been

revised and corrected so many times. To be very specific, there begins a search of records by the

critics and scholars to settle the exact date of composition as well as regarding the original

version of the Elegy. If we consider few of Gray’s events in his life, comments, letters to his

friends (vice-versa), these would not be totally a waste of time and absurdity of method. As is

said, Gray had a recluse sort of personality and he was melancholy’s favourite child. Gray lost

his father in 1741. Richard West died in 1742. The most accepted views regarding the occasion

of the poem is the death of West in 1742. But, Gray’s editor cum friend Mason mentioned in his

Memories that, “I am inclined to believe that the ‘Elegy’ was begun, if not concluded at this

time.” Taking his opinion something factual, we can say that, Gray might have been started

Elegy during his annual stay at Stoke Poges. Then, in 1746, Gray wrote an interesting letter to a

friend Wharton. Where he wrote, “The Muse, I doubt, is gone, and has left me in far worse

company; if she returns, you will hear of her.” Which means, what he started, if he started at all,

writing in 1742 was not completed even in the autumn of 1746. Gray’s most reliable friend

Walpole wrote, “The Churchyard was posterior to West’s death at least three or four years.” This

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

640

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

statement, again, confirms the assumption that the project began around 1746 at Stoke Poges but

Gray was rather tentative in his course of writing. Another death, the death of his aunt Mary

Antrobus in November 1749 intensified the grief even more so that the poet could complete his

elegy and ultimately parceled it to Walpole with a letter on June 12, 1950. In that very letter,

Gray wrote to Walpole that, “I have been here a few days… Having put an end to a thing whose

beginning you saw long ago, I immediately send it to you.” Then Gray’s Elegy was not a mere

poem, rather it was a poem-project written during a period of time i.e. 1746-1750.

Before Robert Dodsley printed the Elegy for publication, Walpole circulated the

manuscript to several of his friends to testify the acceptability of the long poem. Apart from their

friends, it was highly appreciated and impressed a wide class of readers. Its immediate success

and “all copies sold out” condition forced Dodsley to reprint five successive editions in the first

year of its publication. And the more reprints got available the more changes we see in the

words, lines and stanzas in the original version. In addition, Gray had ‘the misfortune of having

for an editor William Mason who conceived it his duty to publish, not what Gray wrote, but what

he thought Gray ought to have written.’(Sampson: 434). Thus, a great piece of literature had to

undergo, from its very inception, so many phases of fluxes. The result is that, it lost its inherent

structural and thematic beauty and the fixity which it had at the hand of its creator.

Interestingly, such a long poem which took almost four years to complete may generally

lead the readers to head-scratching over the genuineness of the original version of text and the

true occasion behind it. Thematically, Gray’s Elegy is an occasional verse. And usually, Richard

West’s death in 1742 is claimed to be the seedbed of this celebrated elegy. But, between 1741

and 1750, as I have stated earlier, Gray’s life had been the unhappy witness of three successive

deaths. The deaths of his father, of his friend and of his aunt. So, without factual record, it would

be signally unwise to say that West’s death is the only occasion and the Youth referred to in the

poem is West. Since there is critic like Joseph Foladore who strongly opposes the idea of

identifying the Youth with West (Joseph was even against identifying the Youth with Gray

himself). Foladore supports himself by saying that, “Attempts to make either West of Gray the

subject of the Elegy invariably pauperize the poem and reflect profoundly on the author’s artistic

intelligence.” (1968.112-113). Actually, it seems to me that Gray was always keen to write

something which would suite to his mind in subject matter and temperament. As is generally

said, Gray tried to finish a poem, the begging of which Walpole saw much earlier. And a scrutiny

over the gradual increment of the autobiographical elements of Gray from three in the first

edition to nine in the later versions of the Elegy obviously deflated the singularity of the Elegy’s

occasion.

According to the Eton College manuscript, Stanzas Wrote in a Country Churchyard was

the title which Gray had originally given to the poem. It was of 22 stanzas. And, it was after the

suggestion of Mason that Gray thoroughly revised the poem and extended it to 32 stanzas.

History has very few examples where a creative genius is led by an editor to extend a finished

product. This extension severely hurts the coherence of the poem and reveals the ‘discordia

concord’ on the part of the poet himself. Two other available manuscripts are preserved in -

Pembroke College and the British Museum. Regarding the revision and expansion, D.C. Tovey

commented in a most derogatory vein in his entry on “Gray” in The Cambridge History of

English Literatur (Vol.-X) that, ‘how pitilessly the poet exercised every stanza which did not

minister to the congruity of his masterpiece.’ More autobiographical elements were forged. The

names of Cato, Tully and Caesar were wiped out to accommodate romanticism (bypassing the

classicism) and revolutionary visionaries, such as Milton, Cromwell were inserted. Graham

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

641

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

Hough commented in The Romantic Poets (1967) that, ‘In the Elegy Gray finds the complete

expression of his private despairs and frustrations, yet the whole perfectly and unobtrusively

place in a wider field of reference.’ The additional three stanzas of the ‘epitaph’ also invited

mush harsh remarks from even Gray’s admirers. W.S.Landor thinks it to be ‘a tin kettle tied to

the poem’s tail.’

Gray’s Elegy: A Reading:

The generally accepted opinion of the critics and readers of Thomas Gray is that Gray’s

development as a poet can be said to be a rhetorical development of English poetry from neo-

classicism to romanticism via the Age of Transition. Beginning with few fragmentary Latin

pieces in didactic vein, Gray came out as a confirm poet only after his father’s death in 1741. His

odes, for which he is still given the status of one of the two best representative poets of the

Eighteenth century, are the Ode on the Spring and the Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton

College. Both came in 1742. The other representative poem of the era is Oliver Goldsmith’s The

Desserted Village. Gray’s two ‘sister odes’ – The Progress of poesy and The bard – are also kept

in the same basket as the finest fruits of his poetic maneuver.

Thomas Gray grew with time. The ebb and flow, touch and go of his relationships

ultimately brought out the best Gray with the passage of time. Taciturn in nature, he was a man

of quality rather than quantity. We frequently hear about his friends, especially about the

‘quadruple alliance’ (Wallpole also confessed his surprise that in spite of having few women

associations, Gray remained a lifelong bachelor). The other three are, two friends from Eton-

Horace Walpole (son of England’s first modern Prime Minister), Richard West (grandson of

Bishop Burnet) and the third is Thomas Ashton. As history records, Richard West was a scholar

with occasional flickering of poetry and had a bent over melancholy. His premature death in

1742 gave Gray the shock and the heirship to the additional melancholy of his dead friend. So,

Gray became a melancholy maniac and stipped himself completely in writing. In his letters to

Richard West, Gray frequently wrote about his congenital melancholy. In a letter written on

December 20, 1735, Gray wrote, “When you have seen one of my days, you have seen a whole

year of my life; they go round and round like the blind horse in the mill, only he has the

satisfaction of fancying he makes a progress and gets some ground.” And on August 22, 1737, he

wrote, “Low spirits are my true and faithful companions; they get up with me, go to bed with me,

make journeys and returns as I do.” He had a very introspective self-consciousness. We come to

know of this from another letter to West from Gray describing the peculiarity of his own

melancholy. Gray stated that,

“ Mine, you are to know, is a white Melancholy, or rather Leucocholy for

the most part; which though it seldom laughs or dances, nor even amounts

to what one calls Joy or Pleasure, yet is a good easy sort of a state, and ca

ne laise de s’amuser. The only fault of it is insipid, which is apt now and

then to give a sort of Ennui, which makes one form certain little wishes

that signify nothing.” (May 27, 1742)

Gray’s best poetic output and the most popular elegy in English Literature, The Elegy

Written in a Country Church-Yard is a perfect fusion of the dignity of subject matter and the

habitual elevation of his craftsmanship. This Elegy is unique in more ways than one. Primarily,

the 18th century audiences were passing through a society which was full of city bred,

fashionable and pompous beaus and belles. It is through this elegy; Gray had extended his

sympathetic flavor from a famous personae in the Augustan city centre to a ‘rude forefather’ of a

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

642

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

small ‘hamlet’. Which is why Gray remains the preeminent precursor of Romanticism, an age

tempered by democratic sentiment and remembered for rural affiliation. It is in the Elegy we can

concur Lyle Glazier’s belief that ‘Each rude forefather of the hamlet has become a type of

mankind. There is thus a double Everyman in the poem – the poet observer, who is Everyman

still alive and reflecting about death, and each rude forefather, who is Everyman already dead

and underground.’

The Elegy starts in the hovering stillness of a dying day. The melancholy-stricken elegist

muses over the life and living of the poor and tries to recover their wispy traces of history from

the grave of time. Nature remains as the befitting background in the opening section of the poem.

Within stanzas 1 to 3, the elegist sets the tone, atmosphere and the back ground of the elegy. As

Graham Hough observes, “Gray is here far less concerned with nature as an object of

contemplation than with the readers- the readers whom he wishes to lull into a resigned,

acquiescent, summer-evening frame of mind.” (The Romantic Poets.14) All of the actions

filtered through the poetic consciousness are either a ‘parting day’, a ‘weary’, ‘homeward’

ploughman or a world which seals up the days’ activities. In the chiaroscuro of the falling dusk,

the day light fades away, everything seems to a pause. The ‘solemn stillness’ of the ‘parting

day’, the ‘droning flight’ of the beetle and the ‘drowsy tinkling’ of the ‘distant folds’ restore the

poet to melancholy and reflection. True to the spirit of a Graveyard poet, Gray finds the

graveyards of the Stoke Poges Church vicinity (where he himself is now buried) as the congenial

locale to reflect on the transience of life. So, the poet begins to muse ‘upon the conditions of

rural life, human potential, and mortality.’(Ousby.291). In stanzas 4 and 5, Gray confirms that

the theme of his elegy would be for those whose ‘narrow cells’ (graves) under the ‘rugged elm

trees’ are not decorated with ‘marble vault’ and no ‘storied urn’ is there to record the life and

living of the rustics. From stanzas 6 to 21, Gray describes the happy bygone days of the ‘rude

forefathers’ of the village as well as of the common folk of the village. Stanza 22 and 23 are deep

revelations of human psychology that the poor and rich alike, all men wish to be remembered

and honoured by their kith and kin. Then there comes a poet shifting, the poet speaker addresses

the story of a village poet in stanzas 24 to 29. Then comes the most controversial ‘Epitaph’

which describes the unfortunate tale of an obscure youth of humble birth, yet to his ‘fame’ and

‘fortune’. Thus, Gray has tried to registere a moral of living as well as of dying.

Within its 32 stanzas, the Elegy depicts a collage of the prospects of the simple and

common man of a village, the death of a village poet (arguable Richard West or Gray himself).

To quote Cleanth Brook from his The Well Wrought Urn (chapter:6), “ For readers who insists

that great poetry can make use of ‘simple eloquence’ – a straightforward treatment of ‘poetic’

material, free from any of the glozings of rhetoric – “Elegy Writted in a Country Churchyard”

must seem the classical instance.” In the same sentence, he continues that “And by the same

token, the ‘Elegy’ would appear to be the most difficult poem to subsume under the theory of

poetic structure maintained in this book.”(Brook.85) Infact, Brook’s reading of the Elegy is

structural or formal. Brushing away all the ‘fallacious’ biases as well as the socio-historical

teasing that makes a text vulnerable , Brook pondered on the fact that, the personifications of

“Ambition”, and “Grandeur” are ‘ironies’. And the whole poem is a ‘classical instance’ to read

under “Irony as a Principle of Structure”. The Elegy is an ironical description of the country

churchyard, the graveyard for the poor villagers in contrast to the Abbey where the fortunate and

the famed are buried. The elegy is tensed with effective binarisms. The life, living and funerals

of the rich have been contrasted with the life, living and funerals of the poor. ‘Storied Urn’ and

‘animated bust’ of the West Minister Abbey are sharply contrasted with ‘neglected spot’ and

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

643

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

‘lowly bed’ of the village graves. The ‘rude forefathers of the small hamlet’ are contrasted with

the ‘ambition and pride’ of people of high ancestry (‘heraldry’). Gays says, -

Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

Elegy (l.13-16)

Raising a question about Brooks’ reading of Gray’s Elegy as a ‘Storied Urn’ that ‘None

of Brooks arguments explain what exactly are the reasons for the Elegy’s claim to greatness’,

Tutun Mukherjee in her resourceful book The Chicago Critics (1991) takes recourse to

R.S.Crane, another New Critic. She says that, “Crane’s explanation is that what is represented in

the poem as its content ‘primarily constitutes the Elegy as a complete and ordered serious lyric

productive of a special emotional pleasure rather than simply a statement of thought’ ”. She

continues that, “Crane calls the poem an imitative lyric of moral choice representing a situation

in which a virtuous sensitive young man of humble birth confronts the prospect of his death

while still to ‘fame and fortune unknown’ and eventually after much disturbance of his mind

reconciles himself to his probable ‘fate’ ” (The Chicago Critics.49)

Again, it can be said that the poem elegizes the fate of the simple and common people in

particular and the loss of the agrarian community life on the wake of urbanization, in general.

Gray depicts a life which is rural and more settled. ‘Leadership’ of family was an accepted way

of life. Gender-wise distribution of labour based on individual skill in meeting the both ends of

life as well as for the betterment of their community was never questioned. It was a life when

critics bothered least about gender-stereotyping that woman would look after busily the domestic

duties and responsibilities (“As busy House Wife Ply her evening cares”) and men folk are the

master of the outside world.

The most moving undercurrent of the Elegy is that Gray’s Elegy strongly pleads for the

people who, mostly, after life’s fruitful toil embrace the grave silently and remain unsung. The

poor villagers who are, forever, laid in their narrow cells are least remembered by the posterity.

Gray appeals that the well off, in whose memories trophies are made on their tombs- equally

come to the ‘bending sickle’ of Shakespeare to meet the inevitable hour. Gray says, -

Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

The short and simple annals of the poor.

Elegy (l.29-32)

Because all the course of life, however fruitful or gorgeous it may seem, lead but to the

grave. And once, death draws the curtain on the stage, neither ‘storied urn’, nor ‘Honour’ nor

Falttery’ nor any ‘animated bust’ can bring back the ‘fleeting breath.’

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust,

Or Flatt'ry soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

Elegy (l.41-44)

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

644

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

The elegist warns “Ambition’, ‘Grandeur’, ‘heraldry’, ‘power’, ‘Beauty’ and ‘wealth’ not

to mock these poor rustics of the little hamlet. Grandeur is not to smile at the ‘short and simple

annals of the poor’. Properly speaking, as said by Brook, of course, the poor do not have

‘annals’. Kingdoms have annals, and so do kings, but the peasant does not. The choice of the

term is ironical, and yet the ‘short and simple’ records of the poor are their ‘annals’ – the

important records for them. Almost two hundred and fifty years ago, Gray had the mind and

sensibility to think of such a ‘history’ that was not the register of the powerful alone. And that

history had to have included the fringe elements; the left out section of the society- was

something what we now called ‘subalternity’ as well as deconstructive historiography.

Aristotle, the ideal student of the ideal teacher of an ideal republic once remarked that

‘Povery is the parent of revolution and crime’. Gray has shown, in much contrary to the aforesaid

philosopher’s dictum, that in spite of having tolerated deprivations of many kinds, the poor never

revolted against the establish system nor do they take recourse to the short-cut crimes that

poverty usually breeds.

As for his Classicism, Gray has the same classical concern with perfection of form as

Pope had. The line ‘The Ploughman homeward plods his weary way’ is said to have caused Gray

hours of trouble. How should it be written? ‘The Ploughman homeward…’ or ‘The homeward

ploughman …’ or ‘Homeward the ploughman…’ or ‘The weary ploughman…’ or ‘Weary, the

ploughman…’ Gray did, infact, as said by Anthony Burgess in Engish Literature (1987) “expend

great trouble on the polishing off his verse, and the Elegy’s easy flow is the result of hard work

more than inspiration.” In every stanza we meet lines that have passed the test of time and

became part of the Englilsh language’s reservoir, sounding almost Shakespearian in their

familiarity, Spenserian in its mellifluousness. But Gray had nothing of the swiftness and fluency

of the great Elizabethan. Every effect was worked for, and Gray deserves his success.

In course of pleading the case for the poor very much like a jury, Gray has elegized the

theme by categorically using ‘death’, ‘chill penury’ and ‘lot’ by personifying each of them. Gray

has shown ‘death’ as a great leveler for all – the have nots and the have lots, ‘chill penury’ as a

repressor and the ‘lot’ (luck) as circumscriber of the poor’s progress. Readers are affirmed that

had they not been poor, they even could have become either a poet (‘celestial fire’), a potent king

(‘rod of empire’) or a gifted musician (‘living lyre’). By using the quantifier ‘some’ before the

proper nouns- Hampden, Milton, Cromwell Gray has only extended the potentials of the poor to

become famous.

Thus, throughout the text, Gray has scattered a philosophy on the art of living as well as

of dying. His metaphysical dispositions leads him to become a votary of the Latin adage,

memento mori (‘remember that you have to die’) and the Biblical monition that ‘from dust we

have come and to dust we would return.’ To establish the case for the poor,Gray used theological

doctrines such as beauty and vanity of earthly life is a hindrance to spiritual salvation, where as

honesty and poverty are good towards immortality of the soul.

Large was his bounty, and his soul sincere,

Heav'n did a recompense as largely send:

He gave to Mis'ry all he had, a tear,

He gain'd from Heav'n ('twas all he wish'd) a friend.

Elegy (l.125-128)

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

645

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

Conclusion:

One of the reasons of the poem’s being loved even after almost two hundred fifty years later is

that it appeals to that mood of self-pity which is always ready to rise in all of us. ‘ The short and

simple annals of the poor’ and ‘ Full many a flower is born to blush unseen’ will bring tears to

the eyes of the toughest and least poetical of men, because they feel that, given the chance, they

could have risen higher in the world. They have not risen high, and here is a poet to lament it

and to comfort them by saying that it does not matter: ‘The paths of glory lead but to the grave.’

To conclude, we can say that, there is left almost no literary master who does not leave a

comment in Gray’s elegy. Few were hostile and few favourable. It only testifies that Elegy has

always been included in the personal canon of any reader of British literature. The most popular

among the opinions is the critical hostility from Johnson, who charged Gray of Whiggism and

depreciated Gray’s adjectival coinage of the word “honied” from its noun “honey”(both

Shakespeare and Milton used it, though).Readers frequently quotes Johnson’s ultimate

appreciation of the Elegy which he ‘rejoiced to concur with the common reader’. Another fact

that confirms the popularity of the elegy that by the end of the 60s of the 20th century, more than

200 imitations and parodies of the Elegy became available in England and America. Not to

mention, its translations into various other languages such as Dutch, German, Greek, Hebrew,

Latin, Spanish and Russian. As I have told earlier, it is the single most poem, after any piece of

Shakespeare, which provide us with so many useful quotations – literary, philosophical,

metaphysical and moral. As a human being, Gray had tremendous height of magnanimity and

prudence. He never wanted to expose his erudite to public. He refused the laureateship in

succession to Colley Cibber only to pay homage to the prestigious laureate-lineage of Shadwell,

Tate, Rowe and Laurence Eusden and wanted it to be crowned more aptly by William

Whitehead. Another academic assignment which Gray bypassed was the Regius Professorship of

Modern History at Cambridge. Along with these, Gray had the perseverance like a student. He

worked diligently in the newly opened British Museum from 1759 to 1761 on the Old English

manuscripts for his intended project of writing the history of English Poetry. George Sampson

ends the entry on Thomas Grey in his The Concise Cambridge History of English Literature

(1995) by stating, “Gray’s projected history of English poetry was never written. The loss is

ours, for his sympathy with the early poets was intense. In his love for the old and his adventures

into the new, he anticipates an age that was to develop both his romantic instincts and his

classical restraint.”(434).As for the permanence as a piece of art, David Kennedy rightly

observes, ‘The elegy remains the urn that is never finally completed but is perpetually being

‘storied’ in front of audience.’(Kennedy. Elegy.2009.)

Works cited:

Abrams, M.H. A glossary of Literary Terms. Singapore : Harcout Asia PTE LTD,

2006. Print.

An Anthology: Poems, Plays and Prose, the University of Burdwan: University

Press, 2005. Print.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well Wrought Urn: Studies in The Structure of Poetry.

Methuen, London: University Paperbacks,1968.Print.

Burgess, Anthony. English Literature: A Survey for Students. Hong

Kong:Longman.1987.Print.

Cuddon, J.A. ed. A dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. Delhi : Maya

Blackwell Boaba House, 1998. Print.

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

646

Research Scholar ISSN 2320 – 6101

www.researchscholar.co.in

An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations Impact Factor 0.998 (IIFS)

Hudson, William henry. An Introduction to the study of Literature. Calcutta :

Radha Publishing House, 2002. Print.

Huogh, Graham. The Romantic Poets. London: Hutchinson and Co.

Ltd.1976. Print.

Kennedy, David. Elegy. London and New York: Routledge, The New Critical

Idiom.2009.Print.

Miyashita, Chuji. “A Note on Thomas Gray’s Elegy.” Htotshubashi Journal of arts

and sciences,7(1): 26-33.Web.<http//hdl.handle,net.10086/4391>

Mukherjee, Tutun. The Chicago Critics: An Evaluation.Delhi India: Academic

Foundation. 1991.Print.

Murfin Ross, Supriya M. Ray. The Bedford Glossary of Critical and Literary

Terms. Boston: Bedford/st. Martin’s, 2003. Print.

Ousby, Ian.Ed. The Wordsworth Companion to Literature in Englis.

Britain:Wordsworth Reference,1992.Print.

Raghunathan, Harriet.Ed. Johnson, Gray, Goldsmith Poets of the mid-eighteenth

century. Delhi:Worldview Publications,2007. Print.

Starr, Herbert W. Twentieth Century Interpretations of Gray’s ‘Elegy’:A

Collection of Critical Essays.New Jeresy: Prentice-Hall.1968.Print.

Vol. 3 Issue II May, 2015

647

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- M.K Naik - A History of Indian English Literature-Sahitya Akademi (2009)Dokument367 SeitenM.K Naik - A History of Indian English Literature-Sahitya Akademi (2009)Akhilesh Roshan83% (6)

- Fields of VisionDokument383 SeitenFields of VisionYuliia Vynohradova100% (19)

- Ruth Morello & A. D. Morrison (Ed.), Ancient Letters. Classical and Late Antique Epistolography PDFDokument392 SeitenRuth Morello & A. D. Morrison (Ed.), Ancient Letters. Classical and Late Antique Epistolography PDFAnonymous hXQMt5100% (1)

- Nietzsche DictionaryDokument369 SeitenNietzsche DictionaryDrMlad100% (24)

- I Lliad Odyssey Epic PlaysDokument81 SeitenI Lliad Odyssey Epic PlaysAbygaile AldanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strengths and Limitations of The Research DesignsDokument9 SeitenStrengths and Limitations of The Research DesignsrishiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eight Maxims of StrategyDokument2 SeitenEight Maxims of StrategyKalkiHereNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Search of Psychic Reflection of A Poet: A Psychoanalytical Study of "Ulysses" by Alfred TennysonDokument7 SeitenIn Search of Psychic Reflection of A Poet: A Psychoanalytical Study of "Ulysses" by Alfred TennysoncoubakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elizabeth Browning ThesisDokument5 SeitenElizabeth Browning Thesislizharriskansascity100% (2)

- The Printed Reader: Gender, Quixotism, and Textual Bodies in Eighteenth-Century BritainVon EverandThe Printed Reader: Gender, Quixotism, and Textual Bodies in Eighteenth-Century BritainNoch keine Bewertungen

- The University of Chicago Press Speculum: This Content Downloaded From 130.208.37.218 On Mon, 05 Dec 2016 14:38:07 UTCDokument5 SeitenThe University of Chicago Press Speculum: This Content Downloaded From 130.208.37.218 On Mon, 05 Dec 2016 14:38:07 UTCNicolas Jaramillo GomezNoch keine Bewertungen

- EssayDokument5 SeitenEssayhamza asifNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Reading Medieval PersonificationDokument15 SeitenThe Art of Reading Medieval PersonificationНанаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Charm and National Spirit of English LiteratureDokument6 SeitenCharm and National Spirit of English LiteratureAcademic JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poetics of A.K RamanujanDokument7 SeitenPoetics of A.K RamanujanAgrimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speakers and AbstractsDokument65 SeitenSpeakers and AbstractsPip Osmond-WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anna Westerstahl Stenport - Locating August Strindberg's Prose - Modernism, Transnationalism, and Setting-University of Toronto Press (2010)Dokument224 SeitenAnna Westerstahl Stenport - Locating August Strindberg's Prose - Modernism, Transnationalism, and Setting-University of Toronto Press (2010)narineh.kasparianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black and White: The "Anglo-Indian" Identity in Recent English FictionVon EverandBlack and White: The "Anglo-Indian" Identity in Recent English FictionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Connecting Cultures, Hong Kong Literature in English, The 1950sDokument21 SeitenConnecting Cultures, Hong Kong Literature in English, The 1950sbrucefanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Analysis of Allusions and Symbols in The Poem "The Wasteland" by Thomas Stearns EliotDokument6 SeitenCritical Analysis of Allusions and Symbols in The Poem "The Wasteland" by Thomas Stearns EliotDanyal KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- FandomDokument16 SeitenFandomElusinosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper On Kenneth Clark NudeDokument2 SeitenPaper On Kenneth Clark NudeCata Badawy YutronichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subhāṣitaratnakoṣa, Ingalls (TRL.) 1965 PDFDokument625 SeitenSubhāṣitaratnakoṣa, Ingalls (TRL.) 1965 PDFMiguelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Language As Living Form in Nineteenth Century Poetry - Armstrong, Isobel PDFDokument232 SeitenLanguage As Living Form in Nineteenth Century Poetry - Armstrong, Isobel PDFNones NoneachNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts of Dying: Literature and Finitude in Medieval EnglandVon EverandArts of Dying: Literature and Finitude in Medieval EnglandNoch keine Bewertungen

- 147.amrita BhattacharyyaDokument17 Seiten147.amrita BhattacharyyaRicha DaimariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moral Values Reflected in "The House On MangoDokument24 SeitenMoral Values Reflected in "The House On MangoDina WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steiner, George. Grammars of CreationDokument13 SeitenSteiner, George. Grammars of Creationshark123KNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Complete Correspondence of Hryhory Skovoroda: Philosopher And PoetVon EverandThe Complete Correspondence of Hryhory Skovoroda: Philosopher And PoetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commonwealth LiteratureDokument13 SeitenCommonwealth LiteratureimuiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- East West Cultural Relations in Ama Ata Aidoos Dilemma of A GhostDokument8 SeitenEast West Cultural Relations in Ama Ata Aidoos Dilemma of A GhostAthanasioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper-Critical Theory The Primacy of The Reader Seminar Paper Submitted To The Pre - Doctoral Department of EnglishDokument7 SeitenPaper-Critical Theory The Primacy of The Reader Seminar Paper Submitted To The Pre - Doctoral Department of EnglishramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modernism in English LiteratureDokument61 SeitenModernism in English LiteratureDanear Jabbar AbdulkareemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Talat Rafi Raza KhanDokument10 SeitenTalat Rafi Raza Khan123prayerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment Khadija Batool: Introduction: What Is Comparative Literature Today?Dokument15 SeitenAssignment Khadija Batool: Introduction: What Is Comparative Literature Today?shah hashmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Literature A BookDokument180 SeitenComparative Literature A BookYuliana Ratnasari100% (2)

- About Us: Archive: Contact Us: Editorial Board: Submission: FaqDokument2 SeitenAbout Us: Archive: Contact Us: Editorial Board: Submission: FaqDr. Pratap Kumar DashNoch keine Bewertungen

- David, 2005, The Task of The Loving TranslatorDokument22 SeitenDavid, 2005, The Task of The Loving TranslatorBarbara MahlknechtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anime Guida Al Cinema D Animazione GiapponeseDokument24 SeitenAnime Guida Al Cinema D Animazione GiapponeseCarmela ManieriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zen and English PoetryDokument13 SeitenZen and English PoetryJosé Carlos Faustino CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Trees in Shakespeare TolkienDokument121 SeitenThe Role of Trees in Shakespeare TolkienMarcos NevesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canonical Dead White European Male: Brown TypeDokument8 SeitenCanonical Dead White European Male: Brown Typeanon_179587Noch keine Bewertungen

- Criticism After Romanticism, 1: Moral Criticism: June 2016Dokument9 SeitenCriticism After Romanticism, 1: Moral Criticism: June 2016Ebrahim BaboojiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final-Module-21st-Century-World-Literature G111Dokument23 SeitenFinal-Module-21st-Century-World-Literature G111forrecoveryemailaccNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Differentiation Theory of Meaning in Indian LogicDokument126 SeitenThe Differentiation Theory of Meaning in Indian Logicpaya3100% (2)

- Intrinsic and Extrinsic ApproachesDokument3 SeitenIntrinsic and Extrinsic ApproachesFaiyaz Khan100% (2)

- M. J. Clarke, B. G. F. Currie, R. O. A. M. Lyne Epic Interactions Perspectives On Homer, Virgil, and The Epic Tradition Presented To Jasper Griffin by Former PupilsDokument456 SeitenM. J. Clarke, B. G. F. Currie, R. O. A. M. Lyne Epic Interactions Perspectives On Homer, Virgil, and The Epic Tradition Presented To Jasper Griffin by Former Pupilsfill100% (2)

- God's Exiles and English Verse: On The Exeter Anthology of Old English PoetryVon EverandGod's Exiles and English Verse: On The Exeter Anthology of Old English PoetryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wolfgang Iser - A Companion - Ben de Bruyn - Companions To Contemporary German Culture 1, 2012 - de Gruyter - 9783110245516 - Anna's ArchiveDokument284 SeitenWolfgang Iser - A Companion - Ben de Bruyn - Companions To Contemporary German Culture 1, 2012 - de Gruyter - 9783110245516 - Anna's ArchiveMarcelo CordeiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laura, Versus The Dark Lady, A Comparative Study of Shakespeare and Petrarch's Sonnets PDFDokument9 SeitenLaura, Versus The Dark Lady, A Comparative Study of Shakespeare and Petrarch's Sonnets PDFGlobal Research and Development ServicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Poetics of Poesis: The Making of Nineteenth-Century English FictionVon EverandThe Poetics of Poesis: The Making of Nineteenth-Century English FictionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To LiteratureDokument10 SeitenIntroduction To LiteratureXimena EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Passage To India AnalysisDokument18 SeitenA Passage To India AnalysisbibaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Aurobindo: A Forward-Looking Traditionalist by Peter HeehsDokument11 SeitenSri Aurobindo: A Forward-Looking Traditionalist by Peter HeehsindianscholarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stylistics Analysis of Holly Thursday I by William BlakeDokument7 SeitenStylistics Analysis of Holly Thursday I by William BlakeTipu Nawaz AuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Study of The Essays of Sri Aurobindo GhoshDokument205 SeitenA Critical Study of The Essays of Sri Aurobindo Ghoshketan kathane100% (1)

- Interview With Prof. YasminDokument9 SeitenInterview With Prof. YasminRanga ChandrarathneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey: A Legacy to the WorldVon EverandLaurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey: A Legacy to the WorldW. B. GerardNoch keine Bewertungen

- 35 PDFDokument327 Seiten35 PDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBBU M.A Eng SyllabusDokument19 SeitenMBBU M.A Eng SyllabusRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBBPGFN100476: Form Submission DateDokument1 SeiteMBBPGFN100476: Form Submission DateRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDFDokument242 SeitenPDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slet Philosophy Paper-IDokument13 SeitenSlet Philosophy Paper-IRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waiting For Godot PDFDokument39 SeitenWaiting For Godot PDFAnonymous M1dOSGTqeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romantic Poetry1Dokument4 SeitenRomantic Poetry1Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17 Chapter-2 PDFDokument27 Seiten17 Chapter-2 PDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fulltext02 PDFDokument24 SeitenFulltext02 PDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ej 1080326Dokument4 SeitenEj 1080326Ebrahim Mohammed AlwuraafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 7 A 38 A 6473 C 47 DDokument24 SeitenEd 7 A 38 A 6473 C 47 DRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 Dr. Baburam Swami1Dokument8 Seiten13 Dr. Baburam Swami1Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- All For Love ResearchDokument9 SeitenAll For Love ResearchRadwaAhmed100% (1)

- 06 - Chapter 3Dokument43 Seiten06 - Chapter 3Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passions Made of Nothing But The Finest PDFDokument8 SeitenPassions Made of Nothing But The Finest PDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 - Chapter 4Dokument76 Seiten08 - Chapter 4Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16 ReferencesDokument5 Seiten16 ReferencesRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1869 1 1873 1 10 20170312Dokument5 Seiten1869 1 1873 1 10 20170312Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 43032664Dokument82 Seiten43032664Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 02 Content PDFDokument1 Seite02 Content PDFRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ben 63 2380Dokument1 SeiteBen 63 2380Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 - Chapter 4Dokument58 Seiten10 - Chapter 4Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13 SummaryDokument24 Seiten13 SummaryRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07chapter 4Dokument16 Seiten07chapter 4Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 199 491 1 PBDokument5 Seiten199 491 1 PBRahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 2 ET V1 S1 - Introduction PDFDokument12 Seiten11 2 ET V1 S1 - Introduction PDFshahbaz jokhioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Love Across The Salt DesertDokument2 SeitenLove Across The Salt DesertRahul Kumar Sen100% (1)

- Love Across The Salt DesertDokument6 SeitenLove Across The Salt DesertTal Aggarwal50% (4)

- English - 2017Dokument6 SeitenEnglish - 2017Rahul Kumar SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Egyptian Origin of Greek MagicDokument8 SeitenEgyptian Origin of Greek MagicAdrian StanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Game Theory: Matigakis ManolisDokument46 SeitenIntroduction To Game Theory: Matigakis ManolisArmoha AramohaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tiainen Sonic Technoecology in The Algae OperaDokument19 SeitenTiainen Sonic Technoecology in The Algae OperaMikhail BakuninNoch keine Bewertungen

- 235414672004Dokument72 Seiten235414672004Vijay ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Group Assignment: in A Flexible-Offline ClassesDokument28 SeitenA Group Assignment: in A Flexible-Offline ClassesRecca CuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines Public SpeakingDokument4 SeitenGuidelines Public SpeakingRaja Letchemy Bisbanathan MalarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roles and Competencies of School HeadsDokument3 SeitenRoles and Competencies of School HeadsPrincess Pauline Laiz91% (23)

- 3rd and 4th Quarter TosDokument2 Seiten3rd and 4th Quarter TosMary Seal Cabrales-PejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern CartographyDokument3 SeitenModern CartographyJulie NixonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics A1Dokument6 SeitenEthics A1dedark890Noch keine Bewertungen

- Future Namibia - 2nd Edition 2013 PDFDokument243 SeitenFuture Namibia - 2nd Edition 2013 PDFMilton LouwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quantitative Research Questions & HypothesisDokument10 SeitenQuantitative Research Questions & HypothesisAbdul WahabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Letting Go of The Words: Writing E-Learning Content That Works, E-Learning Guild 2009 GatheringDokument10 SeitenLetting Go of The Words: Writing E-Learning Content That Works, E-Learning Guild 2009 GatheringFernando OjamNoch keine Bewertungen

- SQ4R StrategyDokument2 SeitenSQ4R StrategyRelu ChiruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fear and Foresight PRTDokument4 SeitenFear and Foresight PRTCarrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nieva Vs DeocampoDokument5 SeitenNieva Vs DeocampofemtotNoch keine Bewertungen

- A3 ASD Mind MapDokument1 SeiteA3 ASD Mind Mapehopkins5_209Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1881 Lecture by William George LemonDokument12 Seiten1881 Lecture by William George LemonTim LemonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elliot Self HandicappingDokument28 SeitenElliot Self HandicappingNatalia NikolovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service BlueprintDokument10 SeitenService BlueprintSam AlexanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bible Parser 2015: Commentaires: Commentaires 49 Corpus Intégrés Dynamiquement 60 237 NotesDokument3 SeitenBible Parser 2015: Commentaires: Commentaires 49 Corpus Intégrés Dynamiquement 60 237 NotesCotedivoireFreedomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ideas To Make Safety SucklessDokument12 SeitenIdeas To Make Safety SucklessJose AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zealot by Reza Aslan, ExcerptDokument19 SeitenZealot by Reza Aslan, ExcerptRandom House Publishing Group86% (7)

- Social Science 1100: Readings in Philippine History: Instructional Module For The CourseDokument15 SeitenSocial Science 1100: Readings in Philippine History: Instructional Module For The CourseXynNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Problem of EvilDokument13 SeitenThe Problem of Evilroyski100% (2)

- 2022 City of El Paso Code of ConductDokument10 Seiten2022 City of El Paso Code of ConductFallon FischerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anthropocentrism 171003130400Dokument11 SeitenAnthropocentrism 171003130400Ava Marie Lampad - CantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar Slides HRM Application Blanks Group 1Dokument13 SeitenSeminar Slides HRM Application Blanks Group 1navin9849Noch keine Bewertungen