Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Copyright Wex

Hochgeladen von

Abdur Rauf RahmaniOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Copyright Wex

Hochgeladen von

Abdur Rauf RahmaniCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

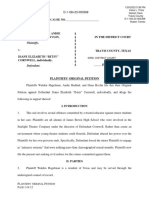

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 1

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey

1909 Act 1976 Act 1988 Berne Agreement

prior to 1/1/78 1/1/78 to 2/28/89 3/1/89 to today

Copyright Requires: Requires: Required prior to 3/1/89.

Notice 1. © symbol or “Copyright” or 1. © symbol or “Copyright” or • Notice option from 3/1/89, but

Requirement “Copr.” or else © forfeited. “Copr.” or else © forfeited. may affect monetary recovery as D

2. Year of the work’s first 2. Year of the work’s first may claim innocent infringement.

publication publication

3. Name of the owner of the 3. Name of the owner of the ©.

©. abbreviations may suffice abbreviations may suffice

Specific locations: No specific location for © notice

• printed matter must appear

on title page or one

immediately following.

date of publication/registration

Duration of 28 years and 28 year renewal 1) Life of author + 50 years Life of author + 50 years

copyright 2) Anonymous/Pseudonymous:

§302 75 years from first publication or

100 years from date of creation,

whichever shorter.

3) Joint works: Last surviving

author’s death + 50 years

Duration of • Prior to 2/15/72 only • From 1/1/78 - current life of

sound protected by state statute and author + 50 years

recordings common law and unaffected

fixed by 1976 Act until 2047

§301(c) • From 2/15/72 through

12/31/77 has 28 year © and

47 year renewal (75 years)

• From 1/1/78 - current life of

author + 50 years

Duration of • All works created but not If works are published before

works ©/published before 1/1/78 will 2002, © protection lasts until

created but be protected until 12/31/2002 12/31/2027 (50 years from

not published per §302. Failure to publish 12/31/77)

before 1/1/78 before 2003 will result in

forfeiture of renewal rights.

§303

• If works are published before

2002, © protection lasts until

12/31/2027 (50 years from

12/31/77)

Duration of Works published from 1/1/50

works will be in their first term of ©

published protection in 1978. Renewal is

during and to be done in the 27th year,

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 2

after 1950 some time after 12/31/77 and

and before within 1976 Act. 47 years

1/1/78 renewal term, 75 total.

• 1st term: 28 years

• Renewal Term: 47 years

Works in Works in second term sget 19

second term extra years tacked on,

as of 1/1/78 protected until 12/31/2005

Forfeiture: Easy to do by any Forfeiture may be cured for

simple omission. No forfeiture omission per § 405(a)(2) when:

if: 1) the work is registered within

• accidental omission when 5 years of publication; and

the owner attempts to comply 2) owner makes reasonable

• omission without consent of effort to add notice to all

© owner unmarked copies sold in the

US.

• 28 years with the ability to

renew for an additional 28

years for total of 56 years

from the time of publication

• Several laws were passed

by Congress extending older

copyrights to terms totaling 75

years.

© begins at C/L state protection exists. • State C/L protection exists but

Federal protection at time of is extinguished with fixation in

publication tangible expression.

• Federal Protection from first

fixation in tangible expression.

Requirements §301

for © 1. Must be fixed in tangible

protection medium of expression per

§106.

2. Must come within the subject

matter of copyright per §§ 102

& 103

When is a 1. Investitive publication: • §101: dissemination to the

work when owner invests himself of public, but not limited &/or

published? federal statutory protection. unauthorized, nor public

2. Divestitive Publication: that performance.

which owner divested himself

of state C/L protection.

• court hates forfeiture and

usually tried to find some

protection for an injured

owner.

May © owner NO. May have to bring suit

bring suit against © office to obtain © if

before not approved initially.

registration?

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 3

Duration: All copyrights end last day of the calendar year of expiration.

e.g. © April 10, 1972, under 1909 act renewal is up to December 31, 2000.

Anonymous §302(c): If a creates a work in 1978 as work for hire, published in 1980, the work goes into PD in

2055.

Joint Works §302(b): A and B create joint work in 1980. A dies in 1990 and B in 2000. Copyright enters the PD

in 2050.

Death Records § 302(e): Year of death is most important and kept by the Register of Copyrights and creates a

presumption of death taking effect 75 years after publication, 100 years after creation, whichever is less. The

Register may certify a report that there is no indication of the author’s existence or had died within the previous

50 years.

Duration of Copyright Works Created But Not Published or Copyrighted Before 1/1/78: §303. All works created

but not copyriighted/published before 1/1/78 will be protected until 12/31/2002 per §302. Failure to publish

before 2003 will result in forfeiture of renewal rights. If works are published before 2002, © protection lasts until

12/31/2027 (50 years from 12/31/77). 12/31/2002 will be s significant date.

e.g. A owns © on letter sent to B in 1911. A dies in 1927 is never published. Copyright lasts until 12/31/2002. If

letter is published before 2003 © is extended another 25 years to 12/31/2027. (Note this is 50 years from

12/31/77).

Summary:

Published or copyrighted before 1/1/78:

75 years (28+47 years)

Unpublished:

Life of author + 50 years. All unpublished works on 1/1/78 will last through 2002, and if subsequently published,

through 2027.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 4

I. REQUIREMENTS FOR PROTECTION

• Once the work has fallen into PD during the period that governs, the subsequent Act will not retrieve the work

from the PD. e.g. any work published without copyright notice prior to 1/1/78 will be PD despite the fact that the

Berne Convention of 1988 would have allowed it to be protected without notice.

• Modern law requires © notice only on commerciably appreciable units e.g. wallpaper with squares may

require © notice on each square, but modern rule probably requires © notice only for each unit that is smalles

amount sold so as to have at least one © symbol on it.

Hasbro v. Sparkle Toys - p. 540

Facts: Takara, Japanese toymaker, designed and manufactured toys in Japan without a trademark. Japan

did not require a trademark, and 213,000 toys were manufactured in Japan as such. Takara sold the

rights to Hasbro which manufactured the toys in the US under a trademark they registered for Takura as

author and Hasbro as copyright claimant. Sparkle copies the Transformers that contain a US copyright

charging them to be PD due to invalid copyright.

Issue: Can the omission of a copyright notice on a product be cured?

Holding: Yes, P. A © owner has 5 years from date of publication to make a reasonable cure.

D Sparkle argues Takara’s manufacture of Transformers without the © symbol injected the product into

the PD.§ 405(a) that the omission of notice from copies of a protected work may be excused or cured

under certain circumstances, in which case the copyright is valid from the moment the work was

created, just as if no omission had occurred. § 405(a)(2) allows a person who publishes a

copyrightable work without notice to hold a kind of incipient copyright in the work for 5 years

thereafter. If the omission is cured in that time through registration and the exercise of “a reasonable

effort, to add notice to all copies that are distributed to the public in the US after the omission has

been discovered.” This is how the 1975 Act allows greater flexibility than the 1909 Act.

Court states rule that even with deliberate omissions, such as takara’s, there is a 5 year cure option. In

addition, all Hasbro had to do was make reasonable effort to cure product manufactured in the US, not the

product released by Takara in Japan.

1. Registration:

• Informal procedure where applicant can rite informal appeal if denied.

Original Appalachian Artworks v. The Toy Loft - p. 556

Failure to supply the © office with information that may be relevant or may jeopardize an application’s

approval may make a subsequently granted license invalid.octrine of “unclean hands.” Finding the

omission were not fraudulent and no intent to deceive, therefore no forfeiture of the ©.

Reasons to register:

1. Registration is not a condition of copyright protection and may be done at any time during © term.

a. § 1976 Act offers incentives to register:

• cure is allowed only for works registered within 5 years after the publication without notice.

• §410(c) limits prima facie effect of registrations made within 5 years of the work

• § 412 provides no awards of statutory damages or attorney’s fees for any infringement before

effective date of registration or any infringement of copyright commenced after first

publication of the work and before the effective date of its registration unless registered within

3 months after first publication of the work.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 5

2. Prior to 3/1/89, §411(a) of 1976 Act required filing before a suit could be brought for works published in the

US. Works published in foreign countries of Berne Convention did not have to be registered to bring suit (a

compromise before the signing of the Convention).

• Deposit: Deposit must be made of a copy of the work within 3 months after receiving written demand

from the Copyright Office.

• Secure Tests: Copyright may be given to standard exams like the bar, and may be returned after the

exam to prevent others from retreiving the questions.

2. Statutory Subject Matter

A. §102 requires (1) originality and (2) fixation in a tangible form.

1. Originality: Left undefined so a s to allow courtsto define and change the standard of what meets the

criteria for originality with the changing times. This standard does not include novelty or ingenuity,

merely origination of the work with the author.

2. Fixation in Tangible Medium of Expression:

• medium may be known now or later developed, form is immaterial as long as semi permanent

medium.

• Fixation is sufficient if the work can be perceived, reproduced or otherwise communicated either

directly or with the aid of a machine. What is made is an original that is fixed, and copies of the

original that can be distributed.

• §301 Unrecorded performance is not fixed, and isonly subject to state C/L or statutory protection,

but not eligible for Federal statutory protection under §103.

§101 fixation includes:

a. If there has been an authorized embodiment ina copy or phonorecord and if that

embodiment is sufficiently stable to permit the work to be perceived, reproduced, or

otherwise communicated for a period more than the transitory duration.

b. Live broadcasts that is being recorded for the first time is treated as if it was a prerecorded

broadcast of a motion picture.

B. Categories of Copyrightable Works

• Illustrative and not limitative, allowing flexibility to include other types of works.

1. Literary works: Does not make qualitative judgments of the work, and may include catalogs,

directories, or factual references.

2. Pictoral, graphic, and sculptural works: §113: Does not make qualitative judgments of the work, and

includes any craftsmanship but not their mechanical or utilitarian aspects as per Mazer. Only those

features that can be identified seperately from the utilitarian use will be protected.

a. e.g. A two dimensional painting on product is seprately identifiable, but the shape of a lampp is not

seprate from the utilitarian use. Therefore a drawing of a fixture may be copyrighted, but not the

specific style of its work in relation to its utility.

a. Mazer v. Stein

Design of a useful article shall be considered a pictorial, graphic or sculptural work only to the extent that

such design incorporates features that can be identified separately from, and capable of existing

independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article. Held that the patentability of statutes, fitted as lamps

or unfitted, does not bar copyright as works of art. The copyright protects originality rather than novelty or

invention—conferring only the sole right of multiplying copies. Thus respondents may not exclude others

from using statuettes of human figures in table lamps; they may only prevent use of copies of their

statuettes as such or as incorporated in some other article. Finite number of shapes as applied to

functional/utilitarian nature.

3. Motion pictures and audiovisual works

• Three elements:

i. series of images

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 6

ii. capability of showing the images in successive order

iii. impression of motion when the images are thus shown.

• Includestapes, video disks and other media, but not:

a. unauthorized live performances/telecasts

b. live telecasts not simultaneously fixed during transmission

c. filmstrips and slidesets that are useful but incapable of being shown in succession creating an

impression of motion.

4. Sound recordings

In any fixed medium such as tapes, records, CDs,

5. Musical works

6. Dramatic works

7. Pantomimes and choreographic works

C. Other Rules

§ 102(b): Nature of Copyright

Copyright only extends to expressions of ideas, not any particularidea, procedure, process, system,

principle or discovery, despite the fact that it is embodied in a work.

§103. Compilations and Derivative Works

• © in a new version only extends to that additional work that has been added to the original

protected or PD work.

• Derivative work: A recasting , transforming or adapting of one or more preexisting works.

• Characters of Fiction: As per J.. Hand in Nichols v. Universal: The less developed the characters,

the less they can be copyrighted; that is the penalty the author must bear for marking them too

indistinctly.

Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.

Ordinary, wrongful appropriation is shown by proving “substantial similarity” of copyrightable expression.

Copyright in play cannot be limited literally to text, else plagiarist could escape by immaterial variations.

Question is whether part is so substantial, and therefore not “fair use” of copyrighted work. When

plagiarist does not take a block out of situation but abstract of whole, decision is more troubling. In

plays, great number of patters on increasing generality will fit equally as more of incident is left out.

There is point where abstraction = idea = uncopyrightable.

• Architecture: protected under §102 and includes overall form as well as plans and drawings.

• Labels: Phrases are not © and labeling usually falls into unfair competition and trademarking.

• Obscene Works: Copyright protects works and the government does not pass judgment whether

they are of sufficient moral and literary value, or it would be unconstitutional.

• US Government: May purchase and hold rights to a © but work done by its employees as part of

their official duties are not considered protectable by ©.

• Works not subject to ©:

a. Short phrases, slogans, mere typographic ornamentations

b. Ideas, plans, methods, but manner of expression is copyrightable.

c. Blank forms, time cards, graph paper, diaries, bank checks and other generic order forms

d. Common property such as standard calendars, height/weight charts, tape measures,

schedules of sporting events or other tables taken from public documents.

3. Original Expression

Supplement from book

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 7

Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures - p. 573

Real life: woman poisons lover in love triangle. Cause-celebre with books published, etc.. Play made based on it with

key things changed, woman poisons lover in love triangle with stricknine in coffee and is revealed through family

association. Movie made substantially similar to play. In its broader outline, a play is never copyrightable. However,

a play may be with out using the dialogue. Speech is only small part of dramatists means of expression. Dramatic

significance of the scenes here was recited almost to the letter. While much of picture owes nothing to the play, it is

enough substantial parts were lifted from the plot and court awarded a percentage of movie proceeds to playwright

attributable to the play’s success.

Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing - p. 573

Facts: Wallace hired P Bleistein to do a lithograph to promote his circus and it included his picture and some other

scenes from the circus. After D Donaldson made reduced copies , P sued for copyright infringement. while it is

possible they may have been used properly for Wallace, the issue is as follows.

Issue: Are chromolithographs designed for advertising purposes not eligible for copyright protection?

Holding: P, no. “A picture is none less a subject of copyright that is used for an advertisement. Copyright was not

limited to the fine arts. Outside both copyright law and competence of courts to assess artistic merits of original

creations.” To hold otherwise would set up the judiciary as an arbiter of artistic quality which it is not equipped to do

so.

Note: There could be a seeming paradox. A better replication, one that is produces far more deftness of

hand, may be guilty of © infringement because it copies the original. A clumsy copy , on the other hand,

may prove to be too crude to constitute a copy and is not an infringement.

Note: This was decided in the opposite in Alva, where P received © protection for an exact replication in

miniature of a Rodin sculpture in the PD. That work was held as constituting sufficient originality, espeially

with the great work that went into it, yet in Tomy, who made three-dimensional works out of the two

dimensional characters, the court ruled that it didn’t take much skill to do so. In Batlin the court did nopt

grant a © for a plastic replica of a cast iron Uncle sam bank in the PD because it was said not to constitute

suffient originality or skill. The plastic model had differed in size and details, yet it seems as though the ©

office is pushing works to embody expressive differences rather than PD copies. In Alfred Bell the court

ruled that a painter’s mezzotint engravings of paintings by the masters were copyrightable because they

exhibited expressive differences. The court says little more than one cannot copy a work.

Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone - p.581

Rule: A factual copilation is eligible for copyright if it features an original selection or arrangement of facts, but the

copyright is limited to the particular selection or arrangement. In no event may the copyright extend to the facts

themselves.

Facts: Rural telephone was a monopoly telephone service that produced a telephone directory in areas it serviced as

a condition of its monopoly status. D Feist offered to pay for the use of D’s directories but was denied. D Feist

subsequently copied at least 1,300 entries and used them in D’s compilation, which included an accumulation of

regional phone books. P sues that D could not copy its work for its directory.

Issue: Is copyright protection extended to a mere compilation of facts?

Holding: D, NO. Facts are not copyrightable unless the compilation of facts contains a modicum of originality such as

an original selection or arrangement. The rerquisite level of creativity required is extremely low. Here the directory

was typical, listing telephone customers by last name and providing address and phone number, all of which are

bare facts and could be copied the same way a street map is factual. The facts are public domain and are available

to every person. Preesident Ford could not stop others from copying the bare facts historical facts from his

autobiography, but he could prevent others from copying his subjective descriptions and portraits of public figures.

Notes: The court rejects the “sweat of one’s brow” theory as copyright’s purpose is to promote the progress of the arts

and sciences, not to reward the labor of authors. Originally the court required the subsequent copier of bare facts to

go out in the streets and perform the same factual compilation. The court requires three items for a compilation to

contain sufficient originality and to be copyrightable:

i. collection and assembly of preexisting facts

ii. selection, coordination and arrangement of those materials

iii. the creation, by virtue of the particular selection, coordination or arrangement, an “original” work of authorship.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 8

• §103 explains that the granted copyright protects only the author’s original contributions, not the facts or information

conveyed. Copyright only protects the elements that owe their origin to the compiler - the selection, coordination and

arrangement of facts.

• A comprehensive listing of 18,000 baseball cards, divided into 5,000 premium cards and 13,000 common cards was

copyrightable because of the creativity and judgment of choosing the premium cards.

• Financial Information v. Moody’s: Moody’s was allowed to copy cards that contained 5 financial five facts that were

available on each card.

• Maps: Not copyrightable unless sufficiently unique. All factual information is available in the public domain.

Improvement in scale, accuracy, and undiscovered landmark’s are sufficient original for © protection.

• Case reports: West was allowed © protection from Lexis’ use of West’s page numbers for its pagination of West’s

reports which was copyrightable. Callaghan v. Meyers extended the protection to title-page, table of cases,

headnotes, statement of facts, etc..

• Functional Works: Some rules and instructions are not copyrightable because the subject matter is too narrow, as are

standard form contracts.

Miller v. Universal City Studios - p. 591

Rule: Factual information is in the public domain and each has the right to avail himself of the facts. The amount of

time spent researching the facts is irrelevant.

Facts: P Miller wrote a book about an unsuccessful, notorious Georgia kidnapping that occurred in the 70s, and

employed over 2,500 hours of research. D Universal approached Miller about purchasing the rights to the book, but

when negotiations never consummmated, D produced a TV movie about the event. P sues D and screenwriter for

copyright infringement.

Issue: Can the product of research of facts be copyrighted?

Holding: D NO. The product of research is not copyrightable as ideas and facts are not copyrightable. © law embodies

the notion that facts are in the PD and can be used by anyone. The expressions of facts may be copyrightable, and

here the judge misled the jury with the incorrect staement that the labor of research is protected by copyright.

Notes: Factual information is in the public domain. Each has the right to avail himself of the facts contained in P’s

book and to use such information, whether correct or incorrect in his own book.

• Even interpretations - correct or incorrect - of factual events are not copyrightable as theories. An alternate theory of

the Watergate incident or who killed JFK is not copyrightable.

Hoehling v. Universal Studios (“Hindenberg”)

P wrote book “Who destroyed the Hindenberg?” as a factual account in an objective reportorial style,

the premise of his extensive research that the Hindenberg had been deliberately sabotaged by a

member of its crew in order to embarrass the Nazis. 10 years later the theory and some facts were

used in a movie. Held no copyright protection to the idea and theory as historical information is

Factual and in the public domain. Each has the right to avail himself of the facts contained in P’s

book and to use such information, whether correct or incorrect in his own book.

Toksvig (Hans Christian Anderson): Historical research is not copyrightable. P wrote an extensive

biography on Hans Christian Anderson with great effort into certifying the details. D copied 24

specific passages and literally translated them into Danish. Court held no copyright exists for

historical fact which is PD and can be collected by any member of the public, although it is

questionable whether the aliteral translation is copyrightale. here it was not.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 9

B. RIGHTS AND REMEDIES

a. The nature of copyright

Baker v. Selden - p.600

Rule: Where the use of an idea requires the copying of the work itself, such copying will not constitute infringement.

On the other hand, if the copying does not involve the use of the art but instead its explanation, then such copying

will constitute an infringement.

Facts:P Baker introduced a book that was an essay to his new system of bookkeeping followed by forms to put the

accounting system to use. The columns on a page were arranged to so the operation of a day or week was

available on a single page. D Baker brought out that acheived the same result but used different forms. P Selden

argues his forms are copyrightable.

Holding: D. The forms are a utilitarian tool for using a noncopyrightable system. Only the author’s unique explanation

of the system is copyrightable. If the system were allowed to be copyrighted the author would have a monopoly on

the system. Copyright is based on originality, not novelty and protects the explanation, not the use of the system

explained.

Notes: This case implies that there are instances that copying is permissible. This is a fallacious assumption that there

is only one written expression of an idea - which is why case law has allowed copying of a contract because it was

for use rather than explanation. Morrissey v. Proctor & Gamble allowed word-for-word copying of contest

instructions, even though more than one form of expression was available, because only a limited number of forms

of expression were possible.

• Some later discussion yields that it is possible that when plans are specific, such as architectural, copyright protects

as it is not a plan for the general public as is an accounting system.

Russell v. Price - p. 604

Rule: The copyright holder of a play may sue one for the unauthorized use of a film that is public domain and a

derivative work based upon the play.

Facts: In 1913, George Bernard Shaw copyrighted the play "Pygmalion." In 1938, MGM produced a film version,

whose copyright protection they did not renew 28 years later in 1966, and it became public domain. The play's

copyright was renewed in 1941, 28 years later, and was granted renewal for 47 years until 1988. In 1975, P

exclusive copyright holders of the film through the play, sued D for renting out copies of the film without

authorization.

Holding: The copyright holder of an original work can sue an unauthorized user of a derivative work that is PD and

uses parts of a copyrighted work. The © on a derivative work only includes the added value to the work which is the

only part of the work that is © and owned outright by the owner of the derivative work. The original concepts and

expressions of the original © work still remain the property of the original owner. When the works are too tightly

bound within each other it is possible that even when a derivative work's copyright expires, the work cannot be used

because too much of its component contains protected works of the original copyright.

Notes: Rohaur is a case with different results that are confined to their special facts.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 10

b. Statutory Rights

• §106. Exclusive Rights in Copyrighted Works

Five fundamental rights of copyright owners, subject to §§ 107-118:

• Numbers i-iii all are usually violated at one time.

i. Reproduction

• The right to reproduce material where the work is duplicated, transcribed or imitated, or simulated

in a fixed form from which can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either

directly or with the aid of a machine."

• For a work to be reproduced it must be sufficiently permanent or stable to permit to be perceived,

reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than a transitory duration."

ii. Adaption

• Derivative works: Exclusive right to prepare may overlap right of reproduction, as some

infringement may take place in intangible form such as a ballet or pantomime or play.

• Violation of copyrighted work occurs in a derivative work when:

- it must be based on a copyrighted work

- a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, etc. or any other form in which way a work

may be recast, transformed, or adopted.

- a detailed commentary on a work inspired by another work is not infringement.

iii. Publication

• The right to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or

other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending.The © owner would have the right to

control the first public distribution or his work.

iv. Performance

§106(4) extends to "literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, and motion pictures and

other audiovisual works and sound recordings."

• Exclusive right of public performance is expanded to include not only motion pictures on video

tape, film and disk, but slides aswell.

• Examples of performance:

- singer performing in public

- broadcasting network is performing when he or she sings a song

- cable television when it transmits the network broadcast

- when an individual plays a phonorecord or tunes in a radio

• Performance may be accomplished using a machine or other device

• Performance is public if:

(i) the performance takes place at a place open to the public or at any place where a

substantial number of persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social

acquaintances is gathered; or

(ii) a performance is transmitted or communicated to a place defined in (i) or to the public, by

means of any device where the members of the public are capable of receiving the

performance or display receive it in the same place or in seperate places and at the same

time or different times.

• Routine meeting of business and government are excluded as the numbers are not substantial.

• Performance in public place may also include wired transmission, and any method

v. Display

• §106(5) gives exclusive right to show a copyrighted work or image of it to the public.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 11

Compulsory Licenses

The Copyright Royalty Tribunal is a creation of the 1976 Act and was set up to administer the five compulsory

licenses. It:

i. Sets statutory royalty rates for all compulsory licenses

ii. Settles disputes concerning distribution of monies collected for cable television and jukebox

performances.

• It is more practical to have a standard method in which to have set prices rather than ongoing

negotion by all interested parties. Most couldn't afford the extensive litigation and negotiation

required for such agreements.

1. Cable Transmissions - §111

• Establishes compulsory license for secondary tramnsmissions by cvable TV systems. A cable system

retransmits a primary signal from a local affiliate into a "secondary signal" to consumers and is liable for

compulsory fees.

2. Phonorecords - §115

• ¢2.75 / work or ¢.5 / minute of playing time or ¢2 per every record manufactured.

3. Jukeboxes - §116

• 1909 Act exempted jukeboxes as not a public performance for profit unless charge is incurred and

reproduction/rendition then occurs.

• $8 / jukebox

4. Public Broadcasting - §118

• nondramatic musical, literary, pictoral and graphic works for use by public broadcasters. Rate to be

determined by the tribunal.

5. Satellite Retransmissions §119

• How compulsory licenses work:

1. As per §115, a phonorecord or non-dramatic musical work is distributed to the public by the © owner

with his right to make first distribution.

2. Thereafter, compulsory license provisions are triggered and the musical work is fair game to anyone

wishing to make independent uses for resale, subject to the compulsory license. In other words, once

party A records their song and it is out on record or other medium, party B can make their own

recording of the song and pay a compulsory license to do so. B must pay statutory royalties.

3. Obtaining a compulsory license: Notice of Intention must be sent to the license owner before filing for

a compulsory license.

• Appliesonly to non-dramatic musical works; it cannot be obtained for a recording of an opera, motion

picture soundtrack, medley of tunes from a Broadway show, etc.. To use dramatic works one must

negotiate with the © owner.

• Purpose of distribution of use of compulsory recordings must be for private use.

• First distribution of the work must have been mmade and authorized by the license owner.

• A substantially modified use must be approvaed by the owner of the work as a derivative work. Non-

conformance may result in a forfeiture of the compulsory license.

• A person is not entitled to compulsory licenses for musical works for the purpose of making an

unauthorized duplication of a musical sound recording originally developed and produced by

another.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 12

• §114(b): Infringement of a sound recording (not musical works)

(1) reproduction via mechanical means

(2) rearranging, remixing, or altering it in some fashion via mechanical means.

• Illustration: B can imitate without permission the sound and style of A's recording of Irving Berling songs without

infringing A's reproduction and adaptive rights in sound recording. B has not infringed the the © in sound

recording,however B may be infringing the copyright by reproduction and adaption right by making the

unauthorized recording.

• Right of Public Display §106(5): Right odf display is limited to public displays (as per the definition of

public) and is considered displayed or performed when transmitted (as per definition of transmission).

• §109(c) Public Display of an Owned Copy

An owner of a copy of a © work, or original, may display that work. He may even charge admission and

display it within the place the copy is located, but he may not broadcast it elsewhere.

• Projection of more than one image at a time may not be shown even at the place of the copy, to

protect the owner's rights, and transmission over television or other media would likewise constitute

an infringement.

Library Photocopying: §108: Allowed for scholarly purposes unless it is systematic and is a substitute for

purchase or subscription. The library collection must be open to the public and

i. The copy reproduced must be a single copy.

ii. It must be made without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage.

Columbia Pictures v. Redd Horne - p. 619

Facts: D Redd Horne operated a video cassette rental outlet. In addition, it offered a service where patrons could view

videotapes in small groups in booths for roughly $5. D did not obtain copyright authorization and P Columbia

Pictures brings copyright infringement suit claiming "unauthorized public performance."

Holding: P. a video rental outfit may not exhibit videos to the public as per §106 of the Copyright act. A videocassette

falls within the definition of an audiovisual work. The First Sale Doctrine is not a defense as per §109(a) since all it

has to do is with the free alienability of rights of selling/renting the item. The court says there is no rental as the

tapes never left the store, nor were they ever in the custody of customers. Since playing a videocassette will result in

a sequential showing of a motion picture's image, it constitutes a performance under §101. The court read the

definition in the statute of what constitutes "publicly" in the disjunctive. To constitute public performance:

(i) the performance takes place at a place open to the public or at any place where a substantial number of

persons outside of a normal circle of a family and its social acquaintances is gathered; or

(ii) a performance is transmitted or communicated to a place defined in (i) or to the public, by means of any device

where the members of the public are capable of receiving the performance or display receive it in the same

place or in seperate places and at the same time or different times.

• The court read that if a place is public, it does not matter how large or small the audience is. If the same copy of a

given work is repeatedly played different members of the public, even at different times, this constitutes public

performance.

Notes: Broadcasting may apply to limited public transmissions such as sending videos to private hotel rooms or

subscribers of a cable service. However, private viewing ina hotel of a videocassette which is not broadcast would

not constitute a public performance if the recipients constitute an ordinary number of people in circle of family or

acquantance. D's hotel rooms could be rented out by members of the public, but become private when a guest takes

it and it may no longer be considered public. There is no exact formula as to size requirements for public

performance.

• The definition of t"transmit" under §101 for further transmission means a communication device and medium such as

radio waves or through coaxial cables, beyond the place of origination. It does not mean physical transport of the

tape or item accross town.

Springsteen v. Plaza Roller Dome - p. 625

Facts: D Plaza Roller Dome operated a roller rink and adjacent miniature golf course. D paid for license for roller rink

and claimed they thought it covered the golf course.The course had 6 small speakers with a very unsophisticated

sound system, very similar to a home system, and covered a 7,500 foot area with radio music. ASCAP brought a

suit for copyright violation from unlawful transmissions.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 13

Holding: D. Court cites 20th Century v. Aiken and uses the Aiken Exemption which states that there is an exemption

of copyright law for small business establishments, or else it would result in a regime of copyright law that would be

unenforceable and inequitable. Aiken held that a small fast food shop (640 square feet) which had 4 small ceiling

speakers and an installed radio, did not fall into performance, but rather the streowner fell into the listener/viewer

category. Not only would it be impossible to enforce a © rule in all such establishments and bars, but it would be

inequitable as it is a single public rendition of the work and to exact tribute would be to go far beyond what is

required for the economic protection orf copyright owners. Here, the speakers were of low quality such that only

standing next to them would produce any real meaningful sound, as well as the fact that the noise level was

sufficiently high in the outdoor course. - despite the much larger size of the area.

Notes: §110(c) exempts from liability:

Communication of a transmission embodying a performance or display of work by the public reception of a

transmission on a single receiving apparatus of the kind commonly used in private homes, unless:

(i) a direct charge is being made to hear the transmission

(ii) the transmission thus received is further transmitted to the public.

• The P argued with Gap Stores, a case where every Gap in the country was sued for infringement, as the Aiken case

was said to be the outer limits of what would not constitute infringement. In addition, Gap is a multimillion dollar

establishment that could afford such licensing fees and not a small establishment like Aiken, and had a well

equipped recessed sound system.

Mirage Editions v. Albuquerque A.R.T. - p. 632

Facts: P Mirage was exclusive publisher of a book of color prints of a famous artist. D was commercially engaged in

transferring the prints to ceramic tile, by cutting out the prints from the book. P sues for infringement. D claims right

of First sale and that it does not fall within the meaning of §101 which defines a derivative work as one that is a form

in which the work is "recast, transformed, or adapted."

Holding: P as a person cannot commercially transfer works onto other surfaces without authorization. The work in

question is a derivative work

Notes: In C.M. Paula v. Logan (1973) the court found that transferring greeting cards on plaques was permitted by the

First Sale Doctrine as it was not specifically adapted and each card was purchased by D who had the right to sell it.

Vicarious Libaility and Contributory Infringement: Parties may be held liable when they advertise or

promote advertising or dissemination of information about the sale of infringing items when they have

knowledge of the infrignerments. Concept is of knowingly participating in a tortious activity. Sony case

illustrates contributory infringement, aiding in the infringement process, and liability will be found only

when there is no substantive use for the product for non-infringing purposes. Vicarious liability will be

found when it is not unfair to do soeven when D had no actual knowledge of the infringing behavior.

• ASCAP: American Society for Composers, Authors and Publishers: A non-profit association to pool the

non-dramatic performance rights in members' musical compositions for licensing. ASCAP would give

blanket licensing and would give blanket licensing, and collect and enforce roylty collections. Radio and

television networks are major sources of ASCAP licencees. BMI is a rival. Both are governed by anti-trust

regulations.

Fair Use: §107

• privilege in others than the owner of a © to use the copyrighted material in a reasonablke manner

without his consent, notwithstanding the monopoly granted to the owner by the copyright.

• Applied where a finding of infringement would either be unfair, or would undermine the progress of

science and the useful arts.

A. Allows limited use of the work in the general scope of fair use for the following, not all inclusive

categories:

i. criticism

ii. comment

iii. news reporting

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 14

iv. teaching (and multiple copies for classroom use)

v. scholarship

vi. research

• Examples of fair use: quotation of passages in scholarly work, illustration or clarification of

author's observations, use in parody of part of the work, summary and/or brief quotations in a

news report, library reproduction to replace a damaged copy,

B. Four factors of Fair Use to be applied to the facts of every case

i. the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is

for non-0profit educational purposes;

ii. the nature of the copyrighted work;

iii. the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

iv. the effect of the use on the potential market or value of the copyrighted work.

• Theories

a. Productive Use theory is that the use uses the work to make a more valuable product such as a

news report or critical report. To copy a record so as not to buy it is a non-productive use

(reproductive) and prohibited.

b. Case by Case determination: Illustrated in Sony Betamax case, as each facts have specific

characteristics that may qualify a use not as infringement but as a fair use of the work.

Sony v. Universal City Studios - p. 644

Rule: If a product in question is capable of significant noninfringing uses then the manufacturer cannot be held liable

for contributory infringement by associtaion.

Facts: In 1970s Sony introduced the Betamax videocassette recorder which enabled users ot record homeTV

programs. Several copyright holders sued D Sony for copyright infringement by its consumers by contributory

infringement. Therefore there are substantial noninfringing uses of the Betamax and Sony is therefore not a

contributory infringer.

1. The recording and copying of significant PD and permissible programs make the recorder a useful and

noninfringing device. Mr. Roger's Neighborhood is one such example of a significant TV show that is proper to

record, as well as numerous other educational materials.

2. Time Shifting uses were accepted by most © owners and in addition, no damages were shown as a result of

the time shifting activities.

Notes: What is important is to not that the use was for non-commercial purposes, and licensing agreements were

impossible. Sony could not approximate and pay for any potential infringements. In addition, the courts decided not

to be in a position to make law and left it for legislature to decide issues on compulsory licenses.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 15

OVERVIEW

COPYRIGHT PATENT TRADEMARK

Protects: “Expression/art” Protects: “Invention/ Protects:

Key concept: Originality application/process” “Identification”

Time to obtain: >6 mos. Key concept: novelty Key concept:

Cost to obtain: $20 Time to obtain: 2 yrs. distinctiveness

Length of protection: life + 50 yrs. Cost to obtain: $2000 Time to obtain: 1 yr.

Length of protection: 17 yrs. Cost to obtain:

$1500

Length of protection:

perpetual

COPYRIGHTS

1. FUNDAMENTALS

What Is A Copyright?

Protection which gives owner exclusive right to do and authorize others to do following (17 U.S.C.A. §106):

Exclusive right to reproduce work.

Exclusive right to prepare derivative works (e.g. translations, abridged versions).

Exclusive right to distribute copies of the work to the public by sale/rental.

Exclusive right to perform the work publicly (e.g.: music, plays, dances, pantomimes, motion pictures).

Exclusive right to display the work publicly (e.g.: paintings, sculptures, photographs).

2. CREATION, OWNERSHIP & DURATION OF COPYRIGHT

When Does Copyright Occur?

PRIOR TO 1976 COPYRIGHT ACT AFTER 1976 COPYRIGHT ACT

No copyright until the work was published with a copyright Work is considered created when fixed in

notice. a medium. 17 U.S.C.A. § 102(a)

Ownership

Ownership is vested initially in the author (17 U.S.C. §201(a)). Generally vested in creator. Special cases,

author may be commissioner or employer or creator.

Ownership of copyright is distinct from ownership of material object in which work is embodied (17 U.S.C.

§202). Absent written assignment, transfer of object or original doesn_t convey copyright an transfer of

copyright conveys no right to object (17 U.S.C. §202).

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 16

AUTHORS Immediately upon creation of work in fixed form (17 U.S.C. §201(a)).

EMPLOYEES & Employer is considered author and owner of copyright (17 U.S.C. §201(b)).

CERTAIN WORKS FOR “Work made for hire” is:

HIRE A work prepared by an employee within the scope of his employment;

or,

Work specially ordered/commissioned for use as a contribution to a

collective work, motion picture or other audiovisual, translation,

supplementary work as a compilation, instructional text, test or

answers or as an atlas IF parties expressly agree in writing that work

shall be considered made for hire.

Definition of employee requires inquiry into following factors:

skill required

source of tools and instrumentalities

location of work

duration of relationship between the parties

method of payment

hired party_s discretion over when and how long to work

regular business of the hiring party

employee benefits

tax treatment of party.

INDEPENDENT Almost never employees and therefore must have a written work for hire

CONTRACTORS agreement to qualify as such. Community for Creative Non-violence v.

Reid

CONTRIBUTORS In collective work, each author retains copyright to own contribution. If

joint work, entitled to equal percentages of ownership unless agreed

otherwise

ASSIGNEES Author may assign rights to another. Must be written and signed by

transferor (17 U.S.C. §204). Recordable (17 U.S.C. §205).

Notice

PRIOR TO MARCH 1, 1989 AFTER MARCH 1, 1989

Copyright notice must appear on published work before it No notice is required by law to copyright

could be protected. Must be affixed to copies in way that a work. Still advisable (17 U.S.C. §§401-

gives reasonable notice of copyright. Must use 6).

Symbol ©/”copyright”/”copr.”

Year of first publication of work

Name of copyright owner.

Registration Is Not Required

Registration permissive but not required. (17 U.S.C. §408(a)) However, registering confers following

benefits:

Prerequisite for filing infringement action (17 U.S.C. §411).

Required in order to be eligible for an award in an infringement action (17 U.S.C. §504(c)). One cannot

bring suit for © infringement unless there is a valid, registered ©.

Provides prima facie evidence of ownership and validity of copyright (17 U.S.C. §410(c)).

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 17

Duration

WORKS CREATED BEFORE WORKS CREATED AFTER

JANUARY 1, 1978: JANUARY 1, 1978:

28 years with the ability to renew for an additional 28 years If one author, life of the author + 50

for total of 56 years. Several laws were passed by years. 17 U.S.C.A. § 302(a)

Congress extending older copyrights to terms totaling 75 If two or more authors = life of last

years. surviving author + 50 years.

If work for hire/anonymous work/

pseudonymous work = 75 years from

publication or 100 years from creation

whichever is shorter. 17 U.S.C.A. §

203(a)(b)(d)

3. COPYRIGHTABLE SUBJECT MATTER

Works Where Copyright Can Arise

LITERARY WORKS Those works other than audiovisual works, expressed in words,

numbers, or other verbal or numerical symbols (e.g.: novels, nonfictional

works, poems, articles, essays, directories, advertising, catalogs,

speeches, and computer programs). Medium is unimportant. (17 U.S.C.

§101)

MUSICAL WORKS Note difference between composition and performance. 1976 Act allows

registration of musical work regardless of medium. Lyrics without music

are literary works (e.g.: music and accompanying lyrics).

DRAMATIC WORKS (e.g.: plays, operas, scripts, screenplays, and accompanying music).

PANTOMIMES & Not inclusive of social dance steps or simple routines. Must be fixed by

CHOREOGRAPHIC filming, diagramming, or notation.

WORKS.

PICTORIAL, GRAPHIC, & Distinction between “applied art” (which are protectable) v. “Industrial

SCULPTURAL WORKS designs” (which aren_t because should get design patent). 17 U.S.C.

§101. Commercial work is also copyrightable unless it consists solely of

a trademark or slogan.

“A picture is none less a subject of copyright that is used for an

advertisement. Copyright was not limited to the fine arts. Outside both

copyright law and competence of courts to assess artistic merits of

original creations.” Bliestein v. Donaldson Lithography Service

MOTION PICTURES & (e.g.: movies, videos, and film strips). any audio-visual display produced

OTHER AUDIOVISUAL by a computer program is fixed in a tangible medium readable by a

WORKS machine and can be copyrighted even though the computer program

producing the display is not copyrighted.

SOUND RECORDINGS Works that result from the fixation of a series of musical. Spoken or other

sounds regardless of the medium in which they are embodied. (17

U.S.C. §101)

Prior to February 15,1972, there was no protection for sound recordings.

After February 15, 1972, included recorded music, voice, and sound

effects. Goldstein v. California.

ARCHITECTURAL Includes overall form of a building as well as arrangement of spaces and

WORKS elements of design. Doesn_t include individual standard features like

common windows, doors, and other staple building components. Also

includes architectural plans. (Architectural Works Copyright Protection

Act of 1990).

DIRECTORIES, “Compilation” is a work formed by collecting and assembling preexisting

COMPILATIONS, & materials or by selecting, coordinating or arranging data in such a way

DERIVATIVE WORKS that the work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship (17

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 18

U.S.C. §101). Protection extends only to original material contributed by

author (17 U.S.C. §103(b)). Protectable because of the selection,

coordination and arrangement of items within. Copyright of a factual

compilation is “thin.” Subsequent compiler is free to use the facts

contained in another_s publication to aid in preparing competing work,

so long as work does not feature the same selection and arrangement.

Feist.

“Collective work”: work in which a number of contributions constituting

separate, independent works are assembled as a collective whole. (17

U.S.C. §101) Form of compilation in which materials collected are

individually copyrightable.

“Derivative work”: work based on one/more preexisting works (e.g.:

translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion

picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgement,

condensation or other form in which work may be recast, transformed, or

adapted. Also includes, editorial revisions, annotations, or elaborations,

(17 U.S.C. §101)

Resulting wok must fall into one of nine categories. (17 U.S.C. §102)

New copyright extends only to original contribution of new author.

Doesn_t include any right to preexisting material. (17 U.S.C. §103(b))

Works Where Copyright Cannot Arise

WORKS YOU OWN A Ownership of copy does not confer any rights to the copyright in the work.

COPY OF: You own the copy, but you cannot enjoy any of the other exclusive rights

of the copyright owner

WORKS IN THE PUBLIC Available for anyone to copy with no limit. Includes works never

DOMAIN copyrighted, expired copyrighted works, works by U.S. government.

See also Plaintiff_s Issued Copyright Invalid.

Idea/Expression Dichotomy

Copyright does not give author right to idea disclosed. Extends only to the expression of the idea (17

U.S.C. §102(b)).

“Merger doctrine”: idea and expression are indistinguishable. Scope of this expression is very limited,

sometimes to virtually verbatim copying. Baker v. Selden, Atari, Inc. v. North American Phillips Consumer

Electronics Corp. For protection of the underlying idea, procedure, etc., the owner must rely on

patent/trademark laws.

Baker v. Selden (distinction between a copy and a use)

Copyrightability of accounting system was at issue. USSC held that since defendant_s books were

arranged differently than original author, it was not infringement to use principles/ideas expounded by

original author. Clear distinction between book and art which it is intended to illustrate. Idea = patent.

Note that written systems and forms generally fail to satisfy requirements of patent system too.

Since all are free to borrow idea, very little copyright protection is afforded to original author of similar

system of accounting/business methods. As result, numerous fields of have very little protection other than

against literal copying.

Morrissey v. Proctor & Gamble Co.

Copyright attaches to a form of expression. With respect to box-top contests, when the manner of expression

of the rules incidental to an uncopyrightable game merges with the idea of the contest itself, copyright is not

appropriate.

Apple Computer, Inc. v. Formula International Inc.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 19

The copyright status of the written rules for a game or a system for the operation of a machine is unaffected

by the fact that those rules direct the actions of those who play the game or carry out the process. That the

words of a program are used ultimately in the implementation of a process, should in no way affect their

copyrightability.

If other programs can be written or created which perform the same function as Apple_s operating system

program, then that program is an expression of the idea and hence copyrightable. Thus Apple seeks to

copyright only its particular set of instructions, not the underlying computer process.

Utilitarian-Nonutilitarian (Functional-Nonfunctional) Dichotomy

Purely utilitarian are not subject to copyright protection. To extent not utilitarian, there is no reason to deny

copyright protection.

Why? Patent protection is reserved to works of utility. Because copyright protection lasts longer and is

granted on very minimal showing of originality, courts try to keep borders well-defined and clear.

Mazer v. Stein

Design of a useful article shall be considered a pictorial, graphic or sculptural work only to the extent that

such design incorporates features that can be identified separately from, and capable of existing

independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.

Held that the patentability of statutes, fitted as lamps or unfitted, does not bar copyright as works of art.

The copyright protects originality rather than novelty or invention—conferring only the sole right of

multiplying copies. Thus respondents may not exclude others from using statuettes of human figures in

table lamps; they may only prevent use of copies of their statuettes as such or as incorporated in some

other article.

Finite number of shapes as applied to functional/utilitarian nature.

As Idea And Expression Merge Or As Utility And Nonutility Narrow, Court Is Faced With Choice

Between Two Decisions:

Where inseparable, there could be no protection.

Where so inseparable, protection should not be completely denied.

Originality

Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service Co.

An author can claim copyright as long as created it himself, even if a thousand people created it before

him. “One man_s alone.” Originality does not imply novelty; it only implies that claimant did not copy it from

someone else.

Work must possesses some minimal degree of creativity. Test doesn_t incorporate novelty or nonobviousness

standard. Very low level of creativity required—some creative spark no matter how crude, humble or

obvious.

Amsterdam v. Triangle Publications, Inc.

Schroeder v. William Morrow & Co.

Originality requirement varies according to whether ideas/information are substance of underlying work.

“Sweat theory of copyright” Demands that author demonstrate the investment of some original work in the

final product. Directories, compilations, etc. are copyrightable only if author has invested original effort into

product.

Originality requirement varies according to whether there is any “form” or “style” to underlying work. When

form is minimal/absent, all that is copyrighted is information. Originality (if any) is supplied by the

investment of original labor by he second author. Impossible to infringe directories where there is no

form/style aside from raw data.

Alfred Bell & Co. v. Catalda Fine Arts, Inc.

Source of subject didn_t originate with reproducer but with original author. Nevertheless, copyrightability is

well established. Copyrightability is based on fact that copyist originated reproduction, if nothing else.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 20

Underlying subject matter is not protected. Copyist is protected from those that may want to reproduce the

reproduction instead of the original. Note, however, that copyist must demonstrate that he has contributed

something to final reproduction. (Originality = distinguishable or substantial variation between original and

reproduction)

Financial Information, Inc. v. Moody_s Investors Service, Inc.

Copyright Act does provide for protection of compilations. Here there were five only facts per card. Did

some minor research to find facts, but little independent creation involved. There was insufficient proof of

independent creation to render Daily Bond Card copyrightable.

West Publishing Co. v. Mead Data Central, Inc.

West publishing takes cases arranges them in geographical reporter system. Arrangement that West

produces through process is the result of considerable labor, talent, and judgment. Arrangement easily

meets modicum of intellectual-creation standard. Protection not given to numbers for own sake, but

because access numbers gives to West_s system of arranging otherwise uncopyrightable material.

West_s case arrangements, an important part of which is internal page citations, are original works of

authorship entitled to copyright protection.

Fixed In A Tangible Form

1976 Copyright Act protects all works of authorship from moment fixed in tangible form, be it film, paper,

tape, hard disc, or any other human or machine readable format. (18 U.S.C. §101)

Works is “fixed” in tangible medium when is sufficiently permanent or stable to permit it to be perceived,

reproduced or otherwise communicated for a period of time more than transitory duration. (18 U.S.C.

§101)

4. COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT

To Claim Infringement, There Must Be:

Ownership of

Copyrightable subject matter

That the defendant has substantially copied

Without any justifiable defense.

Ownership Of

For examples of ownership, see above.

Copyright registration is prima facie evidence of ownership copyright (17 U.S.C. §204).

Copyrightable Subject Matter

For examples of copyrightable, subject matter see above.

For examples of noncopyrightable subject matter, see “Plaintiff_s Issued Copyright Invalid” below.

Mirage Editions, Inc. v. Albuquerque A.R.T. Co.

Protection of derivative rights extends beyond mere protection against unauthorized copying to include the

right to make other versions or, perform, or exhibit the work. Appellant by stripping Naegles from book and

mounting them on ceramic tile, made derivative work. “First sale doctrine” applies only to particular copy

which appellant has purchased and nothing else. Does not bar appellee_s infringement claims. Derivative

works right remain s unimpaired by sale of book.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 21

That The Defendant Has Substantially Copied

DIRECT EVIDENCE Defendant either is caught in the act or admits to copying.

CIRCUMSTANTIAL Copying may be inferred where defendant had both access and the work

EVIDENCE is substantially similar to copyrighted work. Sid & Marty Kroft Television

v. McDonald_s Corp.

To prove access a plaintiff has only to establish that the defendant

had the opportunity to see the work. Kenbrooke Fabrics Inc. v.

Holland Fabrics, Inc.

To prove that works are substantially similar, plaintiff must

demonstrate similarity of idea and expression. Two step process for

determining substantial similarity.

Extrinsic test: objective test where court examines the type

of work involved, the materials and the subject matter and

setting for the object. If found similar or identical, proceed to

step #2. Kroft.

Intrinsic test: “whether ordinary reasonable person would fail

to differentiate between the two works or consider them

dissimilar by reasonable observation.” Narell v. Freeman.

Test is satisfied if the “total concept and feel of the works”

are substantially similar Data East. Must dissect similarities

rather than dissimilarities. Alioti v. R. Dakin & Co. Is the

accused works so similar to the plaintiff_s work that an

ordinary, reasonable person would conclude that the

defendant unlawfully appropriated the plaintiff_s protectable

expression by taking material of substance and value. Take

into account that copyright laws preclude appropriation of

only those elements that are protected by copyright. Atari.

Idea v. Expression. Mazer.

Gaste v. Kaiserman (“Feelings”)

Appellee composed and published song for movie. Because copiers rarely caught red-handed, copying

has traditionally been proven circumstantially by proof of access and substantial similarity. Though

publisher of appellee claimed he had never heard/seen song, he owned company which had contract with

appellant = reasonable opportunity for access.

In some cases similarities between works are so extensive and striking, without more, as to justify an

inference of copying and to prove improper appropriation. Evidence as whole must preclude any

reasonable possibility of independent creation. Such existed in this case. Note that music has limited

range and finite number of elements. Striking similarity must extend beyond themes that are trite or

derived from common source.

Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp.

Real life: woman poisons lover. Cause-celebre with books published, etc. Play made based on it with key

things changed. Movie made substantially similar to play. In its broader outline, a play is never

copyrightable. However, a play may be with out using the dialogue. Speech is only small part of

dramatists means of expression. Dramatic significance of the scenes here was recited almost to the letter.

While much of picture owes nothing to the play, it is enough substantial parts were lifted.

Arnstein v. Porter

To prove infringement, plaintiff must demonstrate that defendant_s copied his work and that he “improperly

appropriated” his expression.

Plaintiff_s legally protectable interest is not his reputation as a musician but his interest in the potential

financial returns from his compositions which derive from the lay public_s approbation of his efforts. The

question, therefore, is whether defendant took from plaintiff_s works so much of what is pleasing to the

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 22

ears of lay listeners, who comprise the audience from which such popular music is composed, that

defendant wrongfully appropriated something which belongs to the plaintiff.

Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.

Ordinary, wrongful appropriation is shown by proving “substantial similarity” of copyrightable expression.

Copyright in play cannot be limited literally to text, else plagiarist could escape by immaterial variations.

Question is whether part is so substantial, and therefore not “fair use” of copyrighted work. When plagiarist

does not take a block out of situation but abstract of whole, decision is more troubling. In plays, great

number of patters on increasing generality will fit equally as more of incident is left out. There is point

where abstraction = idea = uncopyrightable.

Saul Steinberg v. Columbia Pictures Industries. (“Moscow on Hudson”)

Definition of substantial similarity: whether the average lay observer would recognize the alleged copy as

having appropriated from the copyrighted work. Posters had striking stylistic relationship. In this case

while not all scenes identical, many could be mistaken for another. Original picture hung in artist_s office.

Where striking similarity and no evidence of creation independent of the copyrighted source justifies

summary judgment.

Whelan Associates, Inc. v. Jasow Dental Laboratories

There is substantial similarity and hence infringement when there is literal copying of elements of computer

programs provided those elements are expression not ideas. However, in determining whether there is

substantial similarity in the non-literal (non code) aspects of a computer program, the courts are split on

protection for separating protectable expression from unprotectable ideas.

WHELAN ASSOCIATES, INC. v. JASLOW DENTAL COMPUTER ASSOCIATES

LABORATORIES INTERNATIONAL, INC. v. ALTAI, INC.

(“SINGLE IDEA RULE”) (ABSTRACTION-FILTRATION-

COMPARISON TEST)

Liberal infringement standard: the purpose or function of More conservative: views the program as

the work is the work_s idea; everything that is not a combination of constituent structural

necessary to the purpose or function is part of the parts and examines each part, as

expression of the idea. opposed to the program as a whole, to

separate protectable expressions from

unprotectable ideas, and to compare the

protectable expressions with the accused

work.

Without Any Justifiable Defense

For examples of defenses, see below.

5. DEFENSES TO COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT

Plaintiff_s Issued Copyright Invalid

WORKS THAT HAVE NOT BEEN

FIXED IN TANGIBLE FORM

TITLES, NAMES, MOTTOES, e.g.: book titles, company names, group names, pen names,

SLOGANS, WORDS OR pseudonyms, product names, phrases, mottoes, slogans,

PHRASES catchwords, advertising expressions

IDEAS, METHODS, In no case does copyright protection for an original work of

PROCEDURES, AND SYSTEMS authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system,

method of operation, concept, principle or discovery, regardless

of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrate or

embodied in such work.

(17 U.S.C. §102(b)) Apple Computer, Inc. v. Formula

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 23

International Inc.

PLOTS, THEMES, HISTORICAL Basic plot of a story cannot be protected, only the words in which

EVENTS the story is told.

MERE FACTS & COMMON e.g.: calendars, height and weight charts, rulers, or other Lists of

INFORMATION information—can own design but not information.

“Sweat of brow theory”: For many years courts held that

collection that took time and labor to collect (e.g.: lists of

certain persons_ names and addresses) were entitled to

copyright protection.) See Feist Publications v. Rural

Telephone Services: USSC reversed stating that collections

of mere facts cannot be copyrighted. Collection of names

and addresses took no creativity to compile/alphabetize.

Copyright only work for something that took creativity. See

also Financial Information, Inc. v. Moody_s Investors Service,

Inc.: Facts may not be copyrighted. To grant putting copyright

protection based merely on “sweat of the author_s brow”

would risk putting large areas of factual research off-limits

and threaten the public_s unrestrained access to information

Producers of “fact works” have long anticipated copying and

insert into their works phone, arbitrary elements. The blatant

copier copies these phony elements and thereafter is hard

pressed to argue that he took only the “unprotected

elements.” Inadvertent errors of fact or typographical errors

perform a similar role in other cases.

SIMPLE RECIPES & LISTS OF As opposed to a more detailed recipe and compilation.

INGREDIENTS

FORMS, SYSTEMS, CONTEST Where there is some creativity, may be entitled to protection.

BLANKS, AND TESTS However, provided much less protection than other works. Courts

are reluctant to grant protection where work seems coexistent

with underlying idea. (e.g.: blank checks, scorecards, report

forms, order forms, address book, columnar pad, time cards,

graph paper, account books, and diaries). Baker v. Selden

HISTORY Historical facts are in the public domain and not copyrightable,

even though an overall historical work is protectable. A.A.

Hoehling v. Universal City Studios

“SCENES A FARE” Stock or standard literary devices (“incidents, characters or

settings which as a practical matter, indispensable, or at least

standard, in the treatment of a subject”) are not copyrightable.

Hoehling

GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS

TYPE FACES Subject matter (alphabet) is so limited and finite as to preclude

copyrightability

UTILITARIAN OBJECTS If object is designed merely to work in a certain way, design

cannot be copyrighted. Should be covered by patents.

Hoehling v. Universal Studios (“Hindenberg”)

Factual information is in the public domain. Each has the right to avail himself of the facts contained in

plaintiff_s book and to use such information, whether correct or incorrect in his own book. Refuses to

subscribe to the view that an author is absolutely precluded from saving time and effort by referring to and

relying upon prior published material. Thus all allegations rest upon material that is noncopyrightable as a

matter of law.

Property of Michael M. Wechsler

Copyright, Trademark & Patent Survey 24

Your Use Constitutes Exception To Plaintiff_s Copyright

FAIR USE “Equitable rule of reason” which may prevent liability for an unauthorized

use of a work (17 U.S.C. §104). (1976 codification of common law)

Factors considered:

Purpose and character of use (commercial v. Nonprofit);

Nature of the work;

Amount or substantiality of the portion used in relation to the

copyrighted work as a whole; and

Effect of the use upon the potential market for or the value of the

work. This is considered the primary factor. Stewart v. Abend.

Examples of fair and unfair use:

Parody: legal to copy part of a work in a parody of it. Acuff-Rose

Music, Inc. v. Campbell

Limited use: no hard and fast rules. Depends on nature of work. Even

extremely small amount can be illegal if it is “heart of work” Harper &

Row, Publishers v. Nation Enterprises.

Comparative Advertisement: if done in manner generally accepted in

the advertising industry, does not copy essence, and has no

commercial impact. Triangle Publications, Inc. v. Knight-Ridder

Newspapers, Inc.

Unpublished works: not as great a right to use unpublished works as

there is for published works.

Libraries and Archives: libraries are allowed much greater rights to

make copies of copyrighted materials for their own use.

Educational use: more likely to be considered fair use if it is for an

educational purpose. But see Marcus.

PUBLIC Exceptions include:

PERFORMANCES Face to face systemic teaching in nonprofit educational institution (all

types)

Instructional broadcasting (nondramatic literary and musical works)

Religious services (nondramatic literary and musical works)

Nonprofit performances with no admission fee and where no objection

from owner (nondramatic literary and musical works)