Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Arkansas Works Opinion

Hochgeladen von

Law&CrimeOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Arkansas Works Opinion

Hochgeladen von

Law&CrimeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

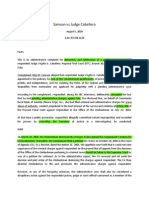

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 1 of 19

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

Argued October 11, 2019 Decided February 14, 2020

No. 19-5094

CHARLES GRESHAM, ET AL.,

APPELLEES

v.

ALEX MICHAEL AZAR, II, SECRETARY, UNITED STATES

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES IN HIS

OFFICIAL CAPACITY, ET AL.,

APPELLANTS

STATE OF ARKANSAS,

APPELLEE

Consolidated with 19-5096

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

(No. 1:18-cv-01900)

Alisa B. Klein, Attorney, U.S. Department of Justice,

argued the cause for federal appellants. With her on the briefs

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 2 of 19

2

were Mark B. Stern, Attorney, Robert P. Charrow, General

Counsel, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and

Brenna E. Jenny, Deputy General Counsel.

Leslie Rutledge, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney

General for the State of Arkansas, Nicholas J. Bronni, Solicitor

General, Vincent M. Wagner, Deputy Solicitor General, and

Dylan L. Jacobs, Assistant Solicitor General, were on the brief

for appellant State of Arkansas.

Ian Heath Gershengorn argued the cause for plaintiff-

appellees. With him on the brief were Jane Perkins, Thomas

J. Perrelli, Devi M. Rao, Natacha Y. Lam, Zachary S. Blau, and

Samuel Brooke.

Kyle Druding was on the brief for amici curiae American

College of Physicians, et al. in support of plaintiffs-appellees.

Edward T. Waters, Phillip A. Escoriaza, and Charles J.

Frisina were on the brief for amici curiae Deans, Chairs, and

Scholars in support of plaintiffs-appellees.

Judith R. Nemsick, Jon M. Greenbaum, and Sunu Chandy

were on the brief for amici curiae Lawyers Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law, et al. in support of appellees and

affirmance.

Before: PILLARD, Circuit Judge, and EDWARDS and

SENTELLE, Senior Circuit Judges.

Opinion for the Court filed by Senior Circuit Judge

SENTELLE.

SENTELLE, Senior Circuit Judge: Residents of Kentucky

and Arkansas brought this action against the Secretary of

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 3 of 19

3

Health and Human Services. They contend that the Secretary

acted in an arbitrary and capricious manner when he approved

Medicaid demonstration requests for Kentucky and Arkansas.

The District Court for the District of Columbia held that the

Secretary did act in an arbitrary and capricious manner because

he failed to analyze whether the demonstrations would promote

the primary objective of Medicaid—to furnish medical

assistance. After oral argument, Kentucky terminated the

challenged demonstration project and moved for voluntary

dismissal. We granted the unopposed motion. The only

question remaining before us is whether the Secretary’s

authorization of Arkansas’s demonstration is lawful. Because

the Secretary’s approval of the plan was arbitrary and

capricious, we affirm the judgment of the district court.

I. Background

Originally, Medicaid provided health care coverage for

four categories of people: the disabled, the blind, the elderly,

and needy families with dependent children. 42 U.S.C.

§ 1396-1. Congress amended the statute in 2010 to expand

medical coverage to low-income adults who did not previously

qualify. Id. at § 1396a(a)(10)(A)(i)(VIII); NFIB v. Sebelius,

567 U.S. 519, 583 (2012). States have a choice whether to

expand Medicaid to cover this new population of individuals.

NFIB, 567 U.S. at 587. Arkansas expanded Medicaid coverage

to the new population effective January 1, 2014, through their

participation in private health plans, known as qualified health

plans, with the state paying premiums on behalf of enrollees.

Appellees’ Br. 14; Gresham v. Azar, 363 F. Supp. 3d 165, 171

(D.D.C. 2019).

Medicaid establishes certain minimum coverage

requirements that states must include in their plans. 42 U.S.C.

§ 1396a. States can deviate from those requirements if the

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 4 of 19

4

Secretary waives them so that the state can engage in

“experimental, pilot, or demonstration project[s].” 42 U.S.C.

§ 1315(a). The section authorizes the Secretary to approve

“any experimental, pilot, or demonstration project which, in the

judgment of the Secretary, is likely to assist in promoting the

objectives” of Medicaid. Id.

Arkansas applied to amend its existing waiver under

§ 1315 on June 30, 2017. Arkansas Administrative Record

2057 (“Ark. AR”). Arkansas gained approval for its initial

Medicaid demonstration waiver in September 2013. In 2016,

the state introduced its first version of the Arkansas Works

program, encouraging enrollees to seek employment by

offering voluntary referrals to the Arkansas Department of

Workforce Services. Dissatisfied with the level of

participation in that program, Arkansas’s new version of

Arkansas Works introduced several new requirements and

limitations. The one that received the most attention required

beneficiaries aged 19 to 49 to “work or engage in specified

educational, job training, or job search activities for at least 80

hours per month” and to document such activities. Id. at 2063.

Certain categories of beneficiaries were exempted from

completing the hours, including beneficiaries who show they

are medically frail or pregnant, caring for a dependent child

under age six, participating in a substance treatment program,

or are full-time students. Id. at 2080–81. Nonexempt

“beneficiaries who fail to meet the work requirements for any

three months during a plan year will be disenrolled . . . and will

not be permitted to re-enroll until the following plan year.” Id.

at 2063.

Arkansas Works included some other new requirements in

addition to the much-discussed work requirements. Typically,

when someone enrolls in Medicaid, the “medical assistance

under the plan . . . will be made available to him for care and

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 5 of 19

5

services included under the plan and furnished in or after the

third month before the month in which he made application.”

42 U.S.C. § 1396a(a)(34). Arkansas Works proposed to

eliminate retroactive coverage entirely. Ark. AR 2057, 2061.

It also proposed to lower the income eligibility threshold from

133% to 100% of the federal poverty line, meaning that

beneficiaries with incomes from 101% to 133% of the federal

poverty line would lose health coverage. Id. at 2057, 2060–61,

2063. Finally, Arkansas Works eliminated a program in which

it used Medicaid funds to assist beneficiaries in paying the

premiums for employer-provided health care coverage. Id. at

2057, 2063, 2073. Arkansas instead used Medicaid premium

assistance funds only to help beneficiaries purchase a qualified

health plan available on the state Health Insurance

Marketplace, requiring all previous recipients of employer-

sponsored coverage premiums to transition to coverage offered

through the state’s Marketplace. Id. at 2057, 2063, 2073.

On March 5, 2018, the Secretary approved most of the new

Arkansas Works program via a waiver effective until

December 31, 2021, but with a few changes. He approved the

work requirements but under the label of “community

engagement.” Id. at 2. The Secretary authorized Arkansas to

limit retroactive coverage to thirty days before enrollment

rather than a complete elimination of retroactive coverage. Id.

at 3, 12. He also approved Arkansas’s decision to terminate the

employer-sponsored coverage premium assistance program.

Id. at 3. The Secretary did not, however, permit Arkansas to

limit eligibility to persons making less than or equal to 100%

of the federal poverty line. Id. at 3 n.1, 11. Instead, the

Secretary kept the income eligibility threshold at 133% of the

federal poverty line. Id. at 3 n.1, 11.

In the approval letter, the Secretary analyzed whether

Arkansas Works would “assist in promoting the objectives of

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 6 of 19

6

Medicaid.” Id. at 3. The Secretary identified three objectives

that he asserted Arkansas Works would promote: “improving

health outcomes; . . . address[ing] behavioral and social factors

that influence health outcomes; and . . . incentiviz[ing]

beneficiaries to engage in their own health care and achieve

better health outcomes.” Id. at 4. In particular, the Secretary

stated that Arkansas Works’s community engagement

requirements would “encourage beneficiaries to obtain and

maintain employment or undertake other community

engagement activities that research has shown to be correlated

with improved health and wellness.” Id. Further, the Secretary

thought the shorter timeframe for retroactive eligibility would

“encourage beneficiaries to obtain and maintain health

coverage, even when they are healthy,” which, in turn,

promotes “the ultimate objective of improving beneficiary

health.” Id. at 5. The letter also summarized concerns raised

by commenters that the community engagement requirement

would “caus[e] disruptions in care” or “create barriers to

coverage” for beneficiaries who are not exempt. Id. at 6–7.

In response, the Secretary noted that Arkansas had several

exemptions and would “implement an outreach strategy to

inform beneficiaries about how to report compliance.” Id.

The new work requirements took effect for those aged 30

to 49 on June 1, 2018, and for those aged 20 to 29 on January

1, 2019. Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d at 172. Charles Gresham

along with nine other Arkansans filed an action for declaratory

and injunctive relief against the Secretary on August 14, 2018.

The district court on March 27, 2019, entered judgment

vacating the Secretary’s approval, effectively halting the

program. Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d at 176–85. In its opinion

supporting the judgment, the district court relied on Stewart v.

Azar, 313 F. Supp. 3d 237 (D.D.C. 2018) (Stewart I), which is

the district court’s first opinion considering Kentucky’s similar

demonstration, Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d at 176. In Stewart I,

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 7 of 19

7

the district court turned to the provision authorizing the

appropriations of funds for Medicaid, 42 U.S.C. § 1396-1, and

held that, based on the text of that appropriations provision, the

objective of Medicaid was to “furnish . . . medical assistance”

to people who cannot afford it. Stewart I, 313 F. Supp. 3d at

260–61.

With its previously articulated objective of Medicaid in

mind, the district court then turned to the Secretary’s approval

of Arkansas Works. First, the district court noted that the

Secretary identified three objectives that Arkansas Works

would promote: “(1) ‘whether the demonstration as amended

was likely to assist in improving health outcomes’;

(2) ‘whether it would address behavioral and social factors that

influence health outcomes’; and (3) ‘whether it would

incentivize beneficiaries to engage in their own health care and

achieve better health outcomes.’” Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d

at 176 (quoting Ark. AR 4). But “[t]he Secretary’s approval

letter did not consider whether [Arkansas Works] would reduce

Medicaid coverage. Despite acknowledging at several points

that commenters had predicted coverage loss, the agency did

not engage with that possibility.” Id. at 177. The district court

also explained that the Secretary failed to consider whether

Arkansas Works would promote coverage. Id. at 179. Instead,

the Secretary considered his alternative objectives, primarily

healthy outcomes, but the district court observed that “‘focus

on health is no substitute for considering Medicaid’s central

concern: covering health costs’ through the provision of free or

low-cost health coverage.” Id. (quoting Stewart I, 313 F. Supp.

3d at 266). “In sum,” the district court held:

the Secretary’s approval of the Arkansas Works

Amendments is arbitrary and capricious because it

did not address—despite receiving substantial

comments on the matter—whether and how the

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 8 of 19

8

project would implicate the “core” objective of

Medicaid: the provision of medical coverage to the

needy.

Id. at 181. The district court entered final judgment on April

4, 2019, and the Secretary filed a notice of appeal on April 10,

2019.

This case was originally a consolidated appeal from the

district court’s judgment in both the Arkansas and Kentucky

cases. The district court twice vacated the Secretary’s approval

of Kentucky’s demonstration for the same failure to address

whether Kentucky’s program would promote the key objective

of Medicaid. Stewart v. Azar, 366 F. Supp. 3d 125, 156

(D.D.C. 2019) (Stewart II); Stewart I, 313 F. Supp. 3d at 274.

On December 16, 2019, Kentucky moved to dismiss its appeal

as moot because it “terminated the section [1315]

demonstration project.” Intervenor-Def.-Appellant’s Mot. to

Voluntarily Dismiss Appeal 1–2 (Dec. 16, 2019), ECF No.

1820334. Neither the government nor the appellees opposed

the motion. Gov’t’s Resp. (Dec. 18, 2019), ECF No. 1820655;

Appellees’ Resp. (Dec. 20, 2019), ECF No. 1821219.

Although the Secretary has considerable discretion to

grant a waiver, we reject the government’s contention that such

discretion renders his waiver decisions unreviewable. The

Administrative Procedure Act’s (APA) exception from judicial

review for an action committed to agency discretion is “very

narrow,” Citizens to Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401

U.S. 402, 410 (1971); see also Dep’t of Commerce v. New York,

139 S. Ct. 2551, 2568 (2019), barring judicial review only in

those “rare instances” where “there is no law to apply,”

Overton Park, 401 U.S. at 410 (internal quotation marks and

citation omitted). The Medicaid statute provides the legal

standard we apply here: The Secretary may only approve

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 9 of 19

9

“experimental, pilot, or demonstration project[s],” and only

insofar as they are “likely to assist in promoting the objectives”

of Medicaid, 42 U.S.C. § 1315(a). Section 1315 approvals are

not among the rare “categories of administrative decisions that

courts traditionally have regarded as committed to agency

discretion.” Dep’t of Commerce, 139 S. Ct. at 2568.

Additionally, the government asked that we address “the

reasoning of the district court’s opinion in Stewart and the

underlying November 2018 HHS approval of the Kentucky

demonstration,” and second that we vacate the district court’s

judgment against the federal defendants in the Kentucky case

Stewart II, 66 F. Supp. 3d 125. Gov’t’s Resp. 1–2. The

appellees opposed both of those additional requests.

Appellees’ Resp. 1–4. We granted the motion to voluntarily

dismiss but declined to vacate the district court’s judgment

against the federal defendants in Stewart II. As to the

government’s first request, we do not rely on the Secretary’s

reasoning in the November 2018 approval of Kentucky’s

demonstration when considering the Secretary’s approval of

Arkansas’s demonstration.

“We review de novo the District Court’s grant of summary

judgment, which means that we review the agency’s decision

on our own.” Castlewood Prods., L.L.C. v. Norton, 365 F.3d

1076, 1082 (D.C. Cir. 2004). Therefore, we will review the

Secretary’s approval of Arkansas Works in accordance with the

Administrative Procedure Act and will set it aside if it is

“arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not

in accordance with law.” 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A); see also C.K.

v. New Jersey Dep’t of Health & Human Servs., 92 F.3d 171,

181–82 (3d Cir. 1996) (applying the arbitrary and capricious

standard of review to a waiver under § 1315); Beno v. Shalala,

30 F.3d 1057, 1066–67 (9th Cir. 1994) (same); Aguayo v.

Richardson, 473 F.2d 1090, 1103–08 (2d Cir. 1973) (same).

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 10 of 19

10

An agency action that “entirely failed to consider an important

aspect of the problem, offered an explanation for its decision

that runs counter to the evidence before the agency, or is so

implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view

or the product of agency expertise” is arbitrary and capricious.

Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass’n of U.S., Inc. v. State Farm Mut.

Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29, 43 (1983).

II. DISCUSSION

A. Objective of Medicaid

The district court is indisputably correct that the principal

objective of Medicaid is providing health care coverage. The

Secretary’s discretion in approving or denying demonstrations

is guided by the statutory directive that the demonstration must

be “likely to assist in promoting the objectives” of Medicaid.

42 U.S.C. § 1315. While the Medicaid statute does not have a

standalone purpose section like some social welfare statutes,

see, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 601(a) (articulating the purposes of the

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program); 42 U.S.C.

§ 629 (announcing the “objectives” of the Promoting Safe and

Stable Families program), it does have a provision that

articulates the reasons underlying the appropriations of funds,

42 U.S.C. § 1396-1. The provision describes the purpose of

Medicaid as

to furnish (1) medical assistance on behalf of

families with dependent children and of aged, blind,

or disabled individuals, whose income and

resources are insufficient to meet the costs of

necessary medical services, and (2) rehabilitation

and other services to help such families and

individuals attain or retain capability for

independence or self-care.

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 11 of 19

11

Id. In addition to the appropriations provision, the statute

defines “medical assistance” as “payment of part or all of the

cost of the following care and services or the care and services

themselves.” 42 U.S.C. § 1396d(a). Further, as the district

court explained, the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of health

care coverage to a larger group of Americans is consistent with

Medicaid’s general purpose of furnishing health care

coverage. See Stewart I, 313 F. Supp. 3d at 260 (citing Pub.

L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119, 130, 271 (2010)). The text

consistently focuses on providing access to health care

coverage.

Both the First and Sixth Circuits relied on Medicaid’s

appropriations provision quoted above in concluding that

“[t]he primary purpose of Medicaid is to enable states to

provide medical services to those whose ‘income and

resources are insufficient to meet the costs of necessary

medical services.’” Pharm. Research & Mfrs. of Am. v.

Concannon, 249 F.3d 66, 75 (1st Cir. 2001) (quoting 42 U.S.C.

§ 1396 (2000)), aff’d, 538 U.S. 644 (2003); Price v. Medicaid

Dir., 838 F.3d 739, 742 (6th Cir. 2016). Similarly, the Ninth

Circuit relied on both the appropriations provision and the

definition of “medical assistance” when describing Medicaid

as “a federal grant program that encourages states to provide

certain medical services” and identifying a key element of

“medical assistance” as the spending of federally provided

funds for medical coverage. Univ. of Wash. Med. Ctr. v.

Sebelius, 634 F.3d 1029, 1031, 1034–35 (9th Cir. 2011).

Beyond relying on the text of the statute, other courts have

consistently described Medicaid’s objective as primarily

providing health care coverage. For example, the Third

Circuit succinctly stated, “We recognize, of course, that the

primary purpose of medicaid is to achieve the praiseworthy

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 12 of 19

12

social objective of granting health care coverage to those who

cannot afford it.” W. Va. Univ. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 885 F.2d

11, 20 (3d Cir. 1989), aff’d, 499 U.S. 83 (1991). Likewise, the

Supreme Court characterized Medicaid as a “program . . .

[that] provides joint federal and state funding of medical care

for individuals who cannot afford to pay their own medical

costs.” Ark. Dep’t of Health & Human Servs. v. Ahlborn, 547

U.S. 268, 275 (2006); see also Virginia ex rel. Hunter Labs.,

L.L.C. v. Virginia, 828 F.3d 281, 283 (4th Cir. 2016) (quoting

Ahlborn in the section of the decision explaining the important

aspects of Medicaid).

The statute and the case law demonstrate that the primary

objective of Medicaid is to provide access to medical care.

There might be secondary benefits that the government was

hoping to incentivize, such as healthier outcomes for

beneficiaries or more engagement in their health care, but the

“means [Congress] has deemed appropriate” is providing

health care coverage. MCI Telecomms. Corp. v. Am. Tel. &

Tel. Co., 512 U.S. 218, 231 n.4 (1994). In sum, “the intent of

Congress is clear” that Medicaid’s objective is to provide

health care coverage, and, as a result, the Secretary “must give

effect to [that] unambiguously expressed intent of Congress.”

Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S.

837, 842–43 (1984).

Instead of analyzing whether the demonstration would

promote the objective of providing coverage, the Secretary

identified three alternative objectives: “whether the

demonstration as amended was likely to assist in improving

health outcomes; whether it would address behavioral and

social factors that influence health outcomes; and whether it

would incentivize beneficiaries to engage in their own health

care and achieve better health outcomes.” Ark. AR 4. These

three alternative objectives all point to better health outcomes

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 13 of 19

13

as the objective of Medicaid, but that alternative objective

lacks textual support. Indeed, the statute makes no mention of

that objective.

While furnishing health care coverage and better health

outcomes may be connected goals, the text specifically

addresses only coverage. 42 U.S.C. § 1396-1. The Supreme

Court and this court have consistently reminded agencies that

they are “bound, not only by the ultimate purposes Congress

has selected, but by the means it has deemed appropriate, and

prescribed, for the pursuit of those purposes.” MCI

Telecomms., 512 U.S. at 231 n. 4; see also Waterkeeper All. v.

EPA, 853 F.3d 527, 535 (D.C. Cir. 2017); Colo. River Indian

Tribes v. Nat’l Indian Gaming Comm’n, 466 F.3d 134, 139–

40 (D.C. Cir. 2006). The means that Congress selected to

achieve the objectives of Medicaid was to provide health care

coverage to populations that otherwise could not afford it.

To an extent, Arkansas and the government characterize

the Secretary’s approval letter as also identifying transitioning

beneficiaries away from governmental benefits through

financial independence or commercial coverage as an

objective promoted by Arkansas Works. Ark. Br. 14, 37–42;

Gov’t Br. 24–25, 32. This argument misrepresents the

Secretary’s letter. The approval letter has a specific section

for the Secretary’s determination that the project will assist in

promoting the objectives of Medicaid. Ark. AR 3–5. The

objectives articulated in that section are the health-outcome

goals quoted above. That section does not mention

transitioning beneficiaries away from benefits. The district

court’s discussion of the Secretary’s objectives confirms our

interpretation of this letter. It identifies the Secretary’s

alternative objective as “improv[ing] health outcomes.”

Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d at 179. There is no reference to

commercial coverage in the Secretary’s approval letter, and

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 14 of 19

14

the only reference to beneficiary financial independence is in

the section summarizing public comments. In response to

concerns about the community engagement requirements

creating barriers to coverage, the Secretary stated, “Given that

employment is positively correlated with health outcomes, it

furthers the purposes of the Medicaid statute to test and

evaluate these requirements as a means to improve

beneficiaries’ health and to promote beneficiary

independence.” Ark. AR 6. But “[n]owhere in the Secretary’s

approval letter does he justify his decision based . . . on a belief

that the project will help Medicaid-eligible persons to gain

sufficient financial resources to be able to purchase private

insurance.” Gresham, 363 F. Supp. 3d at 180–81. We will not

accept post hoc rationalizations for the Secretary’s decision.

See State Farm, 463 U.S. at 50.

Nor could the Secretary have rested his decision on the

objective of transitioning beneficiaries away from government

benefits through either financial independence or commercial

coverage. When Congress wants to pursue additional

objectives within a social welfare program, it says so in the

text. For example, the purpose section of TANF explicitly

includes “end[ing] the dependence of needy parents on

government benefits by promoting job preparation, work, and

marriage” among the objectives of the statute. 42 U.S.C.

§ 601(a)(2). Also, both TANF and the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP) condition eligibility for benefits

upon completing a certain number of hours of work per week

to support the objective of “end[ing] dependence of needy

parents on government benefits.” 42 U.S.C. §§ 601(a)(2),

607(c) (TANF); 7 U.S.C. § 2015(d)(1) (SNAP). In contrast,

Congress has not conditioned the receipt of Medicaid benefits

on fulfilling work requirements or taking steps to end receipt

of governmental benefits.

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 15 of 19

15

The reference to independence in the appropriations

provision and the cross reference to TANF cannot support the

Secretary’s alternative objective either. The reference to

“independence” in the appropriations provision is in the

context of assisting beneficiaries in achieving functional

independence through rehabilitative and other services, not

financial independence from government welfare programs.

42 U.S.C. § 1396-1. Medicaid also grants states the “[o]ption”

to terminate Medicaid benefits when a beneficiary who

receives both Medicaid and TANF fails to comply with

TANF’s work requirements. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 1396u-1(b)(3)(A). The provision gives states, therefore, the

ability to coordinate benefits for recipients receiving both

TANF and Medicaid. It does not go so far as to incorporate

TANF work requirements and additional objectives into

Medicaid.

Further, the history of Congress’s amendments to social

welfare programs supports the conclusion that Congress did

not intend 42 U.S.C. § 1396u-1(b)(3)(A) to incorporate

TANF’s objectives and work requirements into Medicaid. In

1996, SNAP already included work requirements to maintain

eligibility. 7 U.S.C. § 2015(d)(1) (1994). Also in 1996,

Congress passed the Personal Responsibility and Work

Opportunity Reconciliation Act, which replaced Aid to

Families with Dependent Children with TANF and added

work requirements. Personal Responsibility and Work

Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-193,

sec. 103, § 407, 110 Stat. 2105, 2129–34. At the same time, it

added 42 U.S.C. § 1396u-1(b)(3)(A) to Medicaid. Id. at sec.

114, § 1931, 110 Stat. at 2177–80. The fact that Congress did

not similarly amend Medicaid to add a work requirement for

all recipients—at a time when the other two major welfare

programs had those requirements and Congress was in the

process of amending welfare statutes—demonstrates that

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 16 of 19

16

Congress did not intend to incorporate work requirements into

Medicaid through § 1396u-1(b)(3)(A).

In short, we agree with the district court that the

alternative objectives of better health outcomes and

beneficiary independence are not consistent with Medicaid.

The text of the statute includes one primary purpose, which is

providing health care coverage without any restriction geared

to healthy outcomes, financial independence or transition to

commercial coverage.

B. The Approvals Were Arbitrary and Capricious

With the objective of Medicaid defined, we turn to the

Secretary’s analysis and approval of Arkansas’s

demonstration, and we find it wanting. In order to survive

arbitrary and capricious review, agencies need to address

“important aspect[s] of the problem.” State Farm, 463 U.S. at

43. In this situation, the loss of coverage for beneficiaries is an

important aspect of the demonstration approval because

coverage is a principal objective of Medicaid and because

commenters raised concerns about the loss of coverage. See,

e.g., Ark. AR 1269–70, 1277–78, 1285, 1294–95.

A critical issue in this case is the Secretary’s failure to

account for loss of coverage, which is a matter of importance

under the statute. The record shows that the Arkansas Works

amendments resulted in significant coverage loss. In Arkansas,

more than 18,000 people (about 25% of those subject to the

work requirement) lost coverage as a result of the project in just

five months. Ark. Dep’t of Human Servs., Arkansas Works

Program 8 (Dec. 2018),

https://humanservices.arkansas.gov/images/uploads/011519_

AWReport.pdf. Additionally, commenters on the Arkansas

Works amendments detailed the potential for substantial

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 17 of 19

17

coverage loss supported by research evidence. Ark. AR 1269–

70, 1277–78, 1285, 1294–95, 1297, 1307–08, 1320, 1326,

1337–38, 1341, 1364–65, 1402, 1421. The Secretary’s

analysis considered only whether the demonstrations would

increase healthy outcomes and promote engagement with the

beneficiary’s health care. Id. at 3–5. The Secretary noted that

some commenters were concerned that “these requirements

would be burdensome on families or create barriers to

coverage.” Id. at 6. But he explained that Arkansas would have

“outreach and education on how to comply with the new

community engagement requirements” and that Centers for

Medicare and Medicaid Services could discontinue the

program if data showed that it was no longer in the public

interest. Id. The Secretary also concluded that the “overall

health benefits to the [a]ffected population . . . outweigh the

health-risks with respect to those who fail to” comply with the

new requirements. Id. at 7. While Arkansas did not have its

own estimate of potential coverage loss, the estimates and

concerns raised in the comments were enough to alert the

Secretary that coverage loss was an important aspect of the

problem. Failure to consider whether the project will result in

coverage loss is arbitrary and capricious.

In total, the Secretary’s analysis of the substantial and

important problem is to note the concerns of others and dismiss

those concerns in a handful of conclusory sentences. Nodding

to concerns raised by commenters only to dismiss them in a

conclusory manner is not a hallmark of reasoned

decisionmaking. See, e.g., Am. Wild Horse Pres. Campaign v.

Perdue, 873 F.3d 914, 932 (D.C. Cir. 2017) (critiquing an

agency for “brush[ing] aside critical facts” and not “adequately

analyz[ing]” the consequences of a decision); Getty v. Fed.

Savs. & Loan Ins. Corp., 805 F.2d 1050, 1055 (D.C. Cir. 1986)

(analyzing whether an agency actually considered a concern

rather than merely stating that it considered the concern).

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 18 of 19

18

True, the Secretary’s approval letter is not devoid of

analysis. It does contain the Secretary’s articulation of how he

thought the demonstrations would assist in promoting an

entirely different set of objectives than the one we hold is the

principal objective of Medicaid. In some circumstances it may

be enough for the agency to assess at least one of several

possible objectives. See Fresno Mobile Radio, Inc. v. FCC,

165 F.3d 965, 971 (D.C. Cir. 1999). But in such cases, the

statute lists several objectives, some of which might lead to

conflicting decisions. Id.; see also Melcher v. FCC, 134 F.3d

1143, 1154 (D.C. Cir. 1998). For example, in both Fresno

Mobile Radio and Melcher, the statute at issue included five

separate objectives for FCC to consider when creating auctions

for licenses, including “the development and rapid deployment

of new technologies,” “promoting economic opportunity and

competition,” and the “efficient and intensive use of the

electromagnetic spectrum.” 47 U.S.C. § 309(j)(3). In Fresno

Mobile Radio, we recognized that these objectives could point

to conflicting courses of action, so the agency could give

precedence to one or several objectives over others without

acting in an arbitrary or capricious manner. Fresno Mobile

Radio, 165 F.3d at 971; see also Melcher, 134 F.3d at 1154;

Rural Cellular Ass’n v. FCC, 588 F.3d 1095, 1101–03 (D.C.

Cir. 2009) (explaining that an agency may not “depart from”

statutory principles “altogether to achieve some other goal”).

The crucial difference in this case is that the Medicaid statute

identifies its primary purpose rather than a laundry list. The

primary purpose is

to furnish (1) medical assistance on behalf of

families with dependent children and of aged, blind,

or disabled individuals, whose income and

resources are insufficient to meet the costs of

necessary medical services, and (2) rehabilitation

USCA Case #19-5094 Document #1828589 Filed: 02/14/2020 Page 19 of 19

19

and other services to help such families and

individuals attain or retain capability for

independence or self-care.

42 U.S.C. § 1396-1. Importantly, the Secretary disregarded

this statutory purpose in his analysis. While we have held that

it is not arbitrary or capricious to prioritize one statutorily

identified objective over another, it is an entirely different

matter to prioritize non-statutory objectives to the exclusion of

the statutory purpose.

III. CONCLUSION

Because the Secretary’s approval of Arkansas Works was

arbitrary and capricious, we affirm the district court’s judgment

vacating the Secretary’s approval.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- United States v. Dighera, 10th Cir. (2007)Dokument4 SeitenUnited States v. Dighera, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- St. Mary's Academy Vs CarpitañosDokument2 SeitenSt. Mary's Academy Vs CarpitañosKeneth Wilson VirayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Trafficking Smugling ProcDokument36 SeitenHuman Trafficking Smugling ProcHasenNoch keine Bewertungen

- D.2.1 Samson Vs Judge Caballero Case DigestDokument2 SeitenD.2.1 Samson Vs Judge Caballero Case DigestAlejandro de LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- PalemidtermsDokument19 SeitenPalemidtermszarah08Noch keine Bewertungen

- United States v. McCabe, 4th Cir. (2005)Dokument3 SeitenUnited States v. McCabe, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ricarze Vs Court of AppealsDokument5 SeitenRicarze Vs Court of AppealsQueenie BoadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer in Administrative Law by Atty SandovalDokument23 SeitenReviewer in Administrative Law by Atty SandovalRhei BarbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Evidence Admissibility: Introduction To Forensic ScienceDokument40 SeitenLaw of Evidence Admissibility: Introduction To Forensic ScienceRoxanne Torres San PedroNoch keine Bewertungen

- En ConsultaDokument3 SeitenEn ConsultaMJ PerryNoch keine Bewertungen

- ABAKADA Guro v. PurisimaDokument95 SeitenABAKADA Guro v. PurisimaKRIZEANAE PLURADNoch keine Bewertungen

- 245 Legal Office Procedures R 2014Dokument6 Seiten245 Legal Office Procedures R 2014api-250674550Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sachin and ANR V. Jhabbu Lal and ANR Case AnalysisDokument7 SeitenSachin and ANR V. Jhabbu Lal and ANR Case AnalysisParbatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of The Criminal Defence LawyerDokument5 SeitenThe Role of The Criminal Defence LawyerSebastián MooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamDokument16 SeitenCRIM LAW 1 Midterm ExamMichyLG100% (4)

- Mercado - Assignment 2Dokument8 SeitenMercado - Assignment 2Sophia Ysabelle Mercado (sophie)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample ManifestationDokument2 SeitenSample ManifestationChevrolie Maglasang-IsotoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atizado vs. PeopleDokument1 SeiteAtizado vs. PeopleRieland CuevasNoch keine Bewertungen

- CALAUS vs. BUYA, ARIZALA-Falsification of Public Document, Theft, Estafa - RESOLUTIONDokument8 SeitenCALAUS vs. BUYA, ARIZALA-Falsification of Public Document, Theft, Estafa - RESOLUTIONNafiesa ImlaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victim Impact StatementDokument108 SeitenVictim Impact StatementJanet Tal-udanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Julito Sagales V. Rustans Commercial G.R. No. 166554 FactsDokument2 SeitenJulito Sagales V. Rustans Commercial G.R. No. 166554 FactsKing Monteclaro MonterealNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4.digested Manliclic v. CalaunanDokument3 Seiten4.digested Manliclic v. CalaunanArrianne ObiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR No 99026Dokument5 SeitenGR No 99026Cherry UrsuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO Vs Aquino Case DigestDokument2 SeitenWHO Vs Aquino Case DigestMaria Cherrylen Castor Quijada100% (3)

- 3) 342 Scra 20Dokument25 Seiten3) 342 Scra 20LoveAnneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gomez v. CA GR No. 127692 March 10 2004Dokument6 SeitenGomez v. CA GR No. 127692 March 10 2004Joseph John Santos RonquilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alfonso V PasayDokument3 SeitenAlfonso V PasayNikki Estores GonzalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Pedro C. Quinto Alejo Mabanag Tomas B. TadeoDokument5 SeitenPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendants-Appellants Pedro C. Quinto Alejo Mabanag Tomas B. TadeomenggayubeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reciprocal ObligationsDokument6 SeitenReciprocal ObligationsSolarEclipp CandelansaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic vs. Yu - Res JudicataDokument9 SeitenRepublic vs. Yu - Res JudicataJennyNoch keine Bewertungen