Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Epos. Word, Narrative and The Iliad

Hochgeladen von

Alvah GoldbookOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Epos. Word, Narrative and The Iliad

Hochgeladen von

Alvah GoldbookCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Epos: Word, Narrative and the "Iliad" by Michael Lynn-George

Review by: James P. Holoka

The Classical Journal, Vol. 86, No. 1 (Oct. - Nov., 1990), pp. 81-82

Published by: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3297927 .

Accessed: 23/06/2014 09:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Classical Association of the Middle West and South is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Classical Journal.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.46 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JOURNAL

THECLASSICAL 81

mask'sauthenticity."Schliemannin his reportpublishedin the Greekpress claims that

the corpse found underthe other gold mask from GraveV (not the mask itself) "very

much resembles the image which my imagination formed long ago of wide-ruling

Agememnon." Did the genuine masks lack what Schliemannin Mycenae calls "fea-

tures . . . altogetherHellenic"? Was the "AgamemnonMask" created accordingly?

But in that case one would have expected this mask to have been "found" later-

perhapsconsiderablylater-than the others. Traill'sown examinationof the evidence

shows that this was not so.

The minutedamagethat would be caused by the scientific tests desiredby Trailland

Caldermight be justified. But they must supply evidence, not suspicions, before their

theories are accepted.

J. K. ANDERSON

Universityof Californiaat Berkeley

Epos: Word,Narrativeand the "Iliad." By MICHAEL LYNN-GEORGE. Atlantic High-

lands, N.J.: HumanitiesPress International,1988. Pp. xii + 302. $35.00.

Lynn-George'sbook (originallya 1984 Cambridgedissertation)blends literaryanal-

ysis with metacriticalphilippic. He exposes theoreticaldeficiencies in particularpre-

vious critical perspectivesby offering his own readingsof various passages, themes,

etc. The analysis throughoutis broadly deconstructiveand often proceeds on a high

level of abstraction.This is not a book for the novice; readersdesiring criticaldescrip-

tion of the epic couched in a more conventionalidiom of explicationwill do betterto

turnto recent books by, for example, Camps, Griffin, Redfield, or Schein.

In the first part of his book, "Between Two Worlds," Lynn-George explains at

(excessive) length Erich Auerbach'snow venerablecharacterizationof Homeric epic

narrativeas a processionof phenomenain an absolutespatialandtemporalforeground.

He then elucidates passages (e.g., the Teichoskopia)and themes (e.g., the boule of

Zeus) thatdefy Auerbach'ssimplificationof the poem. Thus, the imperfectiveaspectof

the verb in the phraseDios d' eteleieto boule in II. 1.5 contributes"the force of a vast

indefiniteness. .... It producesa plan and a process withoutend, a plan which has no

defined goal and a process which has no specified telos. . . . At the same time it ...

emerges as havingalreadybegun in an indefinitepast, a time withoutlimit priorto 'the

first time' of narrative,an eternitywhich opens across the bordersof this entry into

story, which is itself anythingbut a simple event" (p. 38).

In the second section, "The Epic Theatre:The Languageof Achilles," both Milman

and Adam Parryare the whipping boys. The author again reveals how a theoretical

construct,in this case orality,falsifies the complex realitiesof the narrative.He targets,

in particular,Milman Parry'sreduction of formulaic language to metrical filler and

concomitant diminishing of semantic content. The central problem is, in Lynn-

George's view, our beguilementby the notion of Homer's simplicity and rapidity,an

entrenchedcriticalfable convenuesince MatthewArnold. By attributingthese qualities

to the circumstancesof oral performance,Parryobstructeda more "active and produc-

tive considerationof the possibilities created by words" (p. 80). Lynn-Georgethen

shows what a criticalmethodfreed from such theoreticalrestrictionsmay achieveby an

analysis of the embassy scene of II. 9. Forexample, Odysseus'omission of elements of

Agamemnon'soriginal offer to Achilles is shown to entail "a process of difference,

fixity and movement, preservationand loss" (p. 92) to which Achilles is somehow

sensitive and reactive in his own choice of words. As for Adam Parry'swell-known

accountof the dynamicsof "The Languageof Achilles," Lynn-Georgesees in it only

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.46 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

82 OCTOBER-NOVEMBER

1990

an unwarrantablesegregationof Homericnarrativefromothergreatworksof literature.

"If they [the Parrys]had examined the broadercontext of literature. . . they would

have found that no concerns are more common in literaturethan those by which they

sought to isolate the peculiarityof Homericepic" (p. 98). The struggleof a character

against the conventions of his language is not unique to Homer, nor is it a mark of

linguistic limitationsimposed by an oral poetics.

In his third section, "MortalLoss and Epic Compensation,"Lynn-Georgeattacks

the misconceptionsof a more hoary critical dogma-Analysis. Focusing specifically

on Denys Page's discussion of plot inconcinnitiescenteringon the amnesiaof Achilles

respecting the events of Book 9, he detects a richly elaboratedtheme of "loss and

recompense." A sophisticatedmanagementof conflicting temporalrelationsis again

disclosed: "This altercationin time persists well beyond book ix in the structuringof

the epic narrative.The rift betweenAchilles and the Achaiansshapes the narrativethat

follows with its prolongeddivergencebetween Achilles' continuingexpectation, after

book ix, of an Achaiansupplication,and the Achaianestimationthat such an approach

has alreadybeen made, rejected, and thereforeabandoned. . ." (p. 167).

Part4 of the book, "The Homeless Journey,"is less polemical in orientation,or at

any rate less narrowlydirectedagainst any one critic or school of criticism. It offers

furtherillustrationsof the advantagesof an approachto the text that takes more fully

into account the complexities and the depths (even of paradox) that inform it. For

instance, Lynn-Georgedemonstratesthat "Achilles is placed between the two fathers

Peleus and Priam(xxiv.540-2). In relatingtwo fathers,and in his reflectionon his own

relationto the two, Achilles links them in their grief caused by his simultaneousand

opposed roles ... 'not caringfor' / 'giving care to.' At the same time Achilles resists

any single identity in a speech which sets the two fathersapartin the differencesof

their shareddestiny .. ." (pp. 246-47).

One cannot in a short space detail more than a few of the hundredsof individual

interpretationsLynn-Georgemakes. The readermay,of course, questionthe validityof

discrete critical analyses and even of his overall argumentfor temporaland linguistic

complexity in the epic. Those allergic to deconstructionwill dislike his methods in

general. And, too, the author impedes his argumentsby hideous sentence-structure

(with subordinateclauses nested many levels deep), gratuitousrhetoricalcapers (es-

pecially chiasmus),and aberrantwordchoice. Still, the theoreticalorientationthrough-

out is salubriously "anti-foundational,"markedby a profoundskepticism regarding

doctrinaireapproachesto the Homeric poems. Hence the impatience with literary

critical (and historical) distinctions ascribingto texts of one traditionan exclusively

"surface"meaningand level of intent, but to othersdepth and intricacy.Preconceived

notions of authorship-autonomous vs. traditional,single vs. multiple, oral vs. liter-

ate--are laid bare as debilitatingcritical ideologies deserving no place in the elucida-

tion and adjudicationof artistryin a given text. Lynn-Georgecarefullyavoidsexclusive

claims of insight for his own method: "The Homeric critic works with uncertainties,

where the known is interwovenwith . . . the unknown, perhaps foreverbeyond the

reappropriationwhich makes of history the conquest of time and meaning" (p. 274).

Homeriststolerantof unconventionalapproachesto the Iliad will find much of value

here, in termsboth of textualexplicationand of metacriticaljudgment.

JAMESP. HOLOKA

EasternMichigan University

This content downloaded from 185.2.32.46 on Mon, 23 Jun 2014 09:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Letteratura IngleseDokument35 SeitenLetteratura IngleseLoris AmorosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theater of Fact PDFDokument4 SeitenTheater of Fact PDFCarina CoráNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Darkness of the Present: Poetics, Anachronism, and the AnomalyVon EverandThe Darkness of the Present: Poetics, Anachronism, and the AnomalyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Melammu Project: Ðthe Epic of Gilgamesh and The Homeric EpicsñDokument7 SeitenThe Melammu Project: Ðthe Epic of Gilgamesh and The Homeric EpicsñKaveh Karimi100% (1)

- Smith RhetoricPresencePoets 1985Dokument25 SeitenSmith RhetoricPresencePoets 1985Cry VandalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rice UniversityDokument13 SeitenRice UniversityJARJARIANoch keine Bewertungen

- Loveday Alexander - Fact, Fiction and The Genre of ActsDokument20 SeitenLoveday Alexander - Fact, Fiction and The Genre of ActsNovi Testamenti FiliusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notices: Reality. (Papersfrom The Norwegian Institute at Athens3.) Pp. 178Dokument110 SeitenNotices: Reality. (Papersfrom The Norwegian Institute at Athens3.) Pp. 178yasmineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myth and Method by Laurie L. Patton and Wendy DonigerDokument4 SeitenMyth and Method by Laurie L. Patton and Wendy DonigerAtmavidya1008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Humanities Research AssociationDokument4 SeitenModern Humanities Research AssociationrimanamhataNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Reading Medieval PersonificationDokument15 SeitenThe Art of Reading Medieval PersonificationНанаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dictionary of Narratology, And: Who Says This? The Authority of The Author, The Discourse, and The ReaderDokument4 SeitenDictionary of Narratology, And: Who Says This? The Authority of The Author, The Discourse, and The ReaderLiudmyla Harmash100% (1)

- Narrative and Storytelling For ArchaeoloDokument4 SeitenNarrative and Storytelling For ArchaeoloPaccita AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- ICW Book Forum On Science Fiction: Balay Kalinaw, UP Diliman, 19 April 2017Dokument14 SeitenICW Book Forum On Science Fiction: Balay Kalinaw, UP Diliman, 19 April 2017John Lou Caspe0% (1)

- Universality or Priority The Rhetoric oDokument28 SeitenUniversality or Priority The Rhetoric oLuana Teixeira Barros LuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miriam Fernandez SantiagoDokument12 SeitenMiriam Fernandez SantiagoChiara FenechNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedrich Schlegel and The Myth of IronyDokument27 SeitenFriedrich Schlegel and The Myth of IronyDustin CauchiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allegory and The Origins of PhilosophyDokument43 SeitenAllegory and The Origins of PhilosophyLina Randazzo75% (4)

- Review F. GRAF The Greek MythologyDokument9 SeitenReview F. GRAF The Greek Mythologymegasthenis1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lovecraft 1Dokument23 SeitenLovecraft 1nandan71officialNoch keine Bewertungen

- MASTRONARDE Euripidean Tragedy & TheologyDokument60 SeitenMASTRONARDE Euripidean Tragedy & Theologymegasthenis1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Does The New Testament Imitate - Professor Dennis R. MacDonaldDokument915 SeitenDoes The New Testament Imitate - Professor Dennis R. MacDonaldAlma Slatkovic100% (1)

- Preface / XviiDokument2 SeitenPreface / XviiMagali BarretoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artº Reflections Historiography Holocaust - M MarrusDokument25 SeitenArtº Reflections Historiography Holocaust - M MarrusMichel HacheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eckbert, El Rubio2Dokument20 SeitenEckbert, El Rubio2AlfredoArévaloNoch keine Bewertungen

- J. Hillis Miller's Virtual Reality of Reading: Kur T Fosso and Jerry HarpDokument16 SeitenJ. Hillis Miller's Virtual Reality of Reading: Kur T Fosso and Jerry HarpAlexander Masoliver-AguirreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alber - Moreness and LessnessDokument23 SeitenAlber - Moreness and LessnessMacarenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Domaradzki ClassicalWorld 2017Dokument25 SeitenDomaradzki ClassicalWorld 2017umitNoch keine Bewertungen

- University of California PressDokument30 SeitenUniversity of California PressBe TiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpretation of Absurdity by IntertextualityDokument5 SeitenInterpretation of Absurdity by IntertextualitySînziana Elena MititeluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canlitreviews,+CL145 Reading (Guth) 1Dokument21 SeitenCanlitreviews,+CL145 Reading (Guth) 1amel agency agencyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal-Reconstruction in Critical TheoryDokument4 SeitenJournal-Reconstruction in Critical TheorysemarangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextDokument19 SeitenLodge - Analysis and Interpretation of The Realist TextHumano Ser0% (1)

- (Greek Studies) Casey Dué - Homeric Variations On A Lament by Briseis-Rowman & Littlefield (2002)Dokument153 Seiten(Greek Studies) Casey Dué - Homeric Variations On A Lament by Briseis-Rowman & Littlefield (2002)camilajourdan.uerjNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Myth and Poetics) Gregory Nagy - Greek Mythology and Poetics-Cornell University Press (1992)Dokument368 Seiten(Myth and Poetics) Gregory Nagy - Greek Mythology and Poetics-Cornell University Press (1992)Gianna StergiouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ekfrasis 0Dokument10 SeitenEkfrasis 0Marcela RistortoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)Dokument27 SeitenAllen, W. - The Epyllion - TAPhA 71 (1940)rojaminervaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1988 Richard Levin. Feminist Thematics and Shakespearean Tragedy. PMLA 103.2 (1988) 125-138. JSTORDokument15 Seiten1988 Richard Levin. Feminist Thematics and Shakespearean Tragedy. PMLA 103.2 (1988) 125-138. JSTOR蕭煌元(Patrick 109540036)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fictional Worlds - Thomas G. PavelDokument97 SeitenFictional Worlds - Thomas G. PavelSerbanCorneliu100% (8)

- Athena and TelemachusDokument17 SeitenAthena and Telemachusaristarchos76Noch keine Bewertungen

- G New Historicism Cultural MaterialismDokument22 SeitenG New Historicism Cultural MaterialismElyza CelonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petronian Society NewsletterDokument29 SeitenPetronian Society NewsletterAgustín AvilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2014, Ulysses and Poetics of Cognition, Patrick Colm HoganDokument267 Seiten2014, Ulysses and Poetics of Cognition, Patrick Colm HoganAndika WildanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Realism MiddlemarchDokument31 SeitenRealism MiddlemarchRitika Singh100% (1)

- Greek Mythography in The Roman World by ALAN CAMERON: January 2006Dokument8 SeitenGreek Mythography in The Roman World by ALAN CAMERON: January 2006Luca ClaudiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern Humanities Research Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Modern Language ReviewDokument3 SeitenModern Humanities Research Association Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Modern Language ReviewakunjinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 Liminality and The Short Story (Book) AnnotationsDokument7 Seiten04 Liminality and The Short Story (Book) AnnotationsJose MojicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anne Williams - Natural Supernaturalism - 1985 PDFDokument25 SeitenAnne Williams - Natural Supernaturalism - 1985 PDFWinterPrimadonnaTG100% (1)

- Bill Brown. Introduction Textual MaterialismDokument6 SeitenBill Brown. Introduction Textual MaterialismRoberto Cruz ArzabalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature and Science (Aldous Huxley)Dokument134 SeitenLiterature and Science (Aldous Huxley)Alcila Abby100% (1)

- Poetics Aristotle PaperDokument35 SeitenPoetics Aristotle PaperprosochesatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homerique FolkloreDokument27 SeitenHomerique Folklorealexia_sinoble776Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading and Writing - Intertext - Learning ModuleDokument9 SeitenReading and Writing - Intertext - Learning ModuleChrisha Mae AriasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greek Literature ReviewDokument8 SeitenGreek Literature Revieworlfgcvkg100% (1)

- Did Aristarchus of Samothrace Influence Homeric VulgateDokument11 SeitenDid Aristarchus of Samothrace Influence Homeric VulgateAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dividing HomerDokument12 SeitenDividing HomerAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- A New Papyrus Commentary On The IliadDokument6 SeitenA New Papyrus Commentary On The IliadAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (Rec.)Dokument4 SeitenScholia Graeca in Homeri Iliadem (Rec.)Alvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reciprocities in HomerDokument40 SeitenReciprocities in HomerAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zeus in The Iliad and in The Odyssey. A Chorizontic ArgumentDokument3 SeitenZeus in The Iliad and in The Odyssey. A Chorizontic ArgumentAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Divine Epiphanies in HomerDokument28 SeitenDivine Epiphanies in HomerAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Geloion in The IliadDokument12 SeitenTo Geloion in The IliadAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Timeline of Homer's Iliad PDFDokument1 SeiteTimeline of Homer's Iliad PDFAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Homeric Caesura and The Close of The VerseDokument40 SeitenOn The Homeric Caesura and The Close of The VerseAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Concept of Plot and The Plot of The IliadDokument9 SeitenThe Concept of Plot and The Plot of The IliadAlvah GoldbookNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Financial ExpertDokument16 SeitenThe Financial ExpertVinay Vishwakarma0% (1)

- FRP Topic Integrated Marketing Communications, Internet AdvertisingDokument18 SeitenFRP Topic Integrated Marketing Communications, Internet AdvertisingPrashant SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Films That Sell Moving Pictures and AdveDokument169 SeitenFilms That Sell Moving Pictures and AdveAlek StankovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fill in The GapsDokument4 SeitenFill in The GapsRajeev NiraulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christina Bashford, Historiography and Invisible Musics Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century BritainDokument71 SeitenChristina Bashford, Historiography and Invisible Musics Domestic Chamber Music in Nineteenth-Century BritainVd0Noch keine Bewertungen

- R. M. Ballantyne: The Coral IslandDokument4 SeitenR. M. Ballantyne: The Coral IslandValentina VinogradovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ian SomerhalderDokument4 SeitenIan SomerhalderAysel SafarzadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOP - MassEdit For NIOS 6.8.6Dokument12 SeitenSOP - MassEdit For NIOS 6.8.6Fahmi YasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carbon Alloy SteelDokument2 SeitenCarbon Alloy SteelDeepak HoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Walmart Failure in GermanyDokument4 SeitenWalmart Failure in GermanyAnimesh VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A.I (Alien Invasion) Guard: Android-Based Tower Defense GameDokument16 SeitenA.I (Alien Invasion) Guard: Android-Based Tower Defense GameMeyoor OneacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Golden Dawn - The Invoking Pentagram Ritual of AirDokument2 SeitenGolden Dawn - The Invoking Pentagram Ritual of AirFranco LazzaroniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mattiace: KaitlynDokument1 SeiteMattiace: Kaitlynapi-549332125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fingerstyle Guitar - Fingerpicking Patterns and ExercisesDokument42 SeitenFingerstyle Guitar - Fingerpicking Patterns and ExercisesSeminario Lipa100% (6)

- Parsons Aas Graphic Design 08Dokument18 SeitenParsons Aas Graphic Design 08mushonzNoch keine Bewertungen

- North African Music 2Dokument24 SeitenNorth African Music 2NessaladyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negative AgreementDokument5 SeitenNegative AgreementIrfan HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Table of Electrical Resistivity and ConductivityDokument2 SeitenTable of Electrical Resistivity and ConductivityRajendra Patil0% (1)

- Thought Paper: "Miseducation of The Filipino People" by Renato ConstantinoDokument1 SeiteThought Paper: "Miseducation of The Filipino People" by Renato ConstantinoReynie Ann Sanchez TolentinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Restaurant Dinning HallDokument2 SeitenA Restaurant Dinning HallEvanilson NevesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rime WorksheetsDokument7 SeitenRime WorksheetsMargaret PickettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Archie: Best of Harry Lucey, Vol. 2 PreviewDokument11 SeitenArchie: Best of Harry Lucey, Vol. 2 PreviewGraphic Policy50% (2)

- Final Paper - Final DraftDokument7 SeitenFinal Paper - Final Draftapi-487250493Noch keine Bewertungen

- R. Paulin, Great ShakespeareansDokument212 SeitenR. Paulin, Great ShakespeareansrobertaquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- QUARTER PAST FOUR CHORDS by Avriel and The Sequoias @ PDFDokument1 SeiteQUARTER PAST FOUR CHORDS by Avriel and The Sequoias @ PDFEd RekishiNoch keine Bewertungen

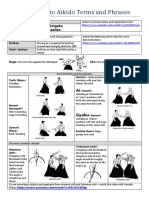

- A Short Guide To Aikido Terms and Phrases PDFDokument2 SeitenA Short Guide To Aikido Terms and Phrases PDFProud to be Pinoy (Devs)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Top CheatsDokument22 SeitenTop CheatsGautham BaskerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Google Chrome: Melissa Brisbin Cherry Hill Public Library (856) 903-1243Dokument65 SeitenGoogle Chrome: Melissa Brisbin Cherry Hill Public Library (856) 903-1243Mihai SpineiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tort NessDokument1 SeiteTort NessMonica CreangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ept - Reading Comprehension2Dokument4 SeitenEpt - Reading Comprehension2Carina SiarotNoch keine Bewertungen