Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Ecology of Human Performance

Hochgeladen von

MariqnOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Ecology of Human Performance

Hochgeladen von

MariqnCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A

person does not exist in a vacuum; the, physical

The Ecology of Human environment as well as social, cultural, and tem-

poral factors all innuence behavior Taken to-

Performance: A gether, those factors that operate external to the person

are identified as context for the purposes of this article.

Framework for Each person's contextual experience is unique, although

many elements are shared among persons.

Considering the Effect Consider the unique way that adults talk to young

children. They may change the tone of their voices, care-

of Context fully select their words, bend down to make themselves

smaller, or use gestures that animate the conversation.

Adults make these adartations hecause they recognize

Winnie Dunn, Catana Brown, Ann the importance of context when talking to young chil-

dren, such as the level of the child's communication skills

McGuigan or how the child might feel about talking to a big person.

lise of these ada[Jtive strategies by an adult speaking at a

work meeting would be considered inaPrropriate be-

Key Word: environment

cause the context of a work meeting dictates other com-

munication methods. The same need for contextually se-

lected behavior exists in manv realms of daily life. A

in theon' and in practice, conte.A·t (as an area o/con- Catholic who attends services at a synagogue derives dif-

cern to occupational therapists) has not receh'ed the ferent meaning from the experience than does herjewish

same attention as per/ormance components and per- friend. When a family eats at a fast-food restaurant, a

formcmce areas. The Ecologr 0/ Human Per/ormance different repertoire of behaviors may he sanctioned than

serves as a framework for considering the effect 0/ if that same family went to a restaurant with menus at the

context. Context is described as a lensFoln Ichich per- table. Context influences behavior and performance in

sons view their world The interrelations!llp a/person many ways; disciplines that address human behavior

and context determines which tasksfall within the

must consider the effect of these contextual features on

person's performa nce range. The Ecology of iiu man

target behaviors.

Performance framework provides guidelines/or en-

compassing context in occupational therajJJ' theory. A recurring theme in the occupational therapv litera-

practice, and resectrch. ture is the concert that environment (i.e., context) is a

critical factor in human performance. Despite this em-

phasis. the potential contribution of contextual features

in evaluation and intelvention relative to performance

components and performance aceas has ceceived little

attention. For example, occupational therapy has manv

assessment~ that examine muscle strength. social skills.

vestibular function, dressing, or use of leisure time. How-

evec, contextual features such as the physical qualities of

an environment, the cultural background of the person,

or the effect of friendships on performance are often

missing fcom assessment tools tvpicallv used in occupa-

tional thecapy. The Ecologv of Human Performance

(EHP) framework has been developed hv the occupation-

Winnie Dunn, PhD. om FAOTA is Pmfessot' and Chair, Occupa- al therapv faculty members at the Cniversity of Kansas in

tional Therapy Euucation. 3033 Rohinson, Universitl of Kan- response to the lack of consideration for the complexities

sas Medical Center, 3901 Rainhow Boulevard. Kansas Citl·. of context. The framework provides a structure for think-

Kansas 66160-7602. ing of context as a kev vaciahle in assessment and inter-

Catana Brown, 1\01 CHI" is A'isisrant Professor, Occupational vention planning, while elucidating the inherent dangers

Thet'apy Education, Univet'sitv of Kansas Medical Center, Kan- in examining perfocmance out of context.

sas City, Kansas. Ecology is concerned with the interrelationships of

organisms and their environments. Occupational therapv

Ann McGuigan. PhD is Assistant Pmfessor. Occupational Ther-

is interested in the interrelationship of humans and their

apy Education. Universitv of Kansas Medical Center. Kansas

contexts and the effect of these relationships on perform-

City, Kansas.

ance; hence this ft'amework is entitled the Ecologv of

Tbis article /l·U.\' acceptedfor PlliJIicutlOn '/aimeliT ]9. 199-1 Human Performance.

Tbe American Journal of Occupational Tberapy 595

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

The EHP framework provides guidelines directed at affect and are affected by their Context. Although the

including contextual features in occupational therapy re- interactional relationship between person and environ-

search and practice (Mosey, 1992). It draws from occupa- ment is of primary importance to environmental psychol-

tional therapy and social science knowledge to contribute ogists, none has described this process as completely as

a compJemenrary per:;pecrive of ecological prlnciples. As Bruner (1989). He developed the concept of transacrional

a framework, it delineates and defines the relevant con- contextuaJism as a process in which the person con-

cepts and describes relationships among variables. It pro- structs the self in the context of the environment. For

vides direction for the development of specific frames of example, a child who grows up in a large family develops

reference concerned with context or the reexamination a different construction of self than a child who grows up

of existing frames of reference and their attention to con- without siblings.

text. The following literature review acknowledges the Lawton's conceptualization of environment more

major contribution of others in the development of this closely resembles that of the EHP than do those of other

framework and provides the groundwork for understand- environmental psychologists. He presented a broader

ing the EHP. concert of environment that includes the personal, su-

prapersonal, and social as well as the physical (Lawton,

1982). Applying Murray's (1938) concept of environmen-

Relevant Literature from Social Science

tal press to the physical environment, Lawton (1982) de-

The EHP framework is founded on and synthesizes the veloped an ecological model of aging that describes the

work of scholars in several disciplines who have consid- dynamics of ecological change, competence, and environ-

ered the interaction between person and environment. mental press in which a person's environment affects

Much of the original work was conducted by environmen- perceptions of competence. In this model, behavior is

tal psychologists who examined the interrelationshir of thought to be "a function of the competence of the indi-

the physical environment and human behavior or experi- vidual and the environmental press of the situation"

ence. In environmental psychology, persons are consid- (p. 43).

ered to be interdependent with their immediate environ- Hall (1983) and Zerubavel (198]) have examined the

ment; the focus of research is on the interaction of the concept of time as an aspect of environment. Both con-

physical elements of a rerson's immediate environment sidered time as context. Hall portrayed time as a factor

with behavior (Holahan, 1986; Wicker, 1979). that is different when persons live it and when they con-

Although the EHP framework shares this emphasis sider it. He argued for a contextually bound, culturally

on examining the interdependent relationship between idiosyncratic, realistic concept of time. Zerubaval asserted

the person and the physical environment, it expands the that time is a major parameter of environment and that

concept of context-environment to include physical, tem- the two must mesh to produce a meaningful gestalt.

roral, social, and cultural elements. Employing a broader Csikszentmihalyi (1990) described "flow" experiences in

definition of environment allows researchers to make ex- which persons are so immersed in a selected task that

rlicit those elements that have frequently been left im- they are unaware of the passage of time. These authors'

plicit by the environmental psychologists. For example, discussions of time as context provide excellent examples

Wicker (1979) described the effect of settings on behavior of the im portance of considering time to be a com ronent

and detailed how behavior might be modified to be ap- of context.

propriate for a particular environment. Implicit in his Several issues have been raised by those who have

analysis is the assumption of a shared concept of the considered the relationship of environment to behaVior.

external environment. The use of context in the EHP Many authors have distinguished between the rheno-

framework balances the emphasis on the external envi- menological and physical nature of the environment. The

ronment presented in environmental psychology and EHP recognizes the role played by both. Gibson (1986)

suggests that the researcher-practitioner consider what discussed both these aspects in his consideration of the

the environment means to the person. relation between ecological context and visual percep-

Hart (1979) conceptualized the environment as an tion. He suggested that the environment is both physical

instrument of socialization. He presented the concept of and phenomenological in that persons perceive objects

environmental competence as the "knowledge, skill and in the environment by the affordances they offer. The

confidence to use the environment to carry out one's own environment-context is meaningful to the person by

goals and to enrich one's experience" (p. 343). Like other what it offers or allows the person. The EHP framework

environmental psychologists, he emphasized that the incorporates this interrretive phenomenological per-

process of learning about self and the environment is spective in its consideration of the relationship between

interactional and he limited the concept of environment the person and context.

to the physical environment. Developmental psychologists have also examined

The idea that context and person are interactional is the effect of environment on behavior. For the most part,

fundamental to the EHP. It is assumed that persons both they have emphasized social aspects of environment.

596 July 1994, Volume 48, Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Bronfenbrenner's (1979) ecological model for human physical, social, and phenomenological experience.

development applied an ecological systems model to The concept of environment in theoretical occupa-

human development It presented a system of social tional therapy literature is typically explained from two

relationships that provided the context for child develop- positions. In one, the environment is described primarily

ment. Bronfenbrenner also developed the concept of as a tool employed by the therapist in the intervention

ecological validity, in which he argued that research was process. For example, Llorens (1970) defined occupa-

nor valid unless it was grounded in context. The EHP tional therapy intervention as the provision of environ-

framework might enable professionals to consider ments that assist persons whose developmental cycle has

whether therapeutic intervention could be valid if it were been disrupted, Fidler and Fidler (1978) explained that

nor grounded in context. persons develop skills and mastery through interaction

Vygorsky (1978) also examined the contribution that with the human and nonhuman environment. She appre-

social environment makes to development. Wertsch ciated the individuality of this in teraction and recognized

(1985) summarized Vygorsky's principles by describing the influence of social and cultural norms, King (1978)

how context could affect development in the theory of described intervention as the use of the environment to

the zone of proximal development. For Vygotsky, the elicit adaptive responses.

zone of proximal development was the distance between In the other position, the relationship of the environ-

a child's actual development and a higher level of poten- ment and the per-son is char-acterizec! from the perspec-

tial development. Vygorsky argued that intervention dur- tive of gener-al systems theor-y, The application of gener-al

ing periods of sensitivity might allow the child to develop systems theory to occupational ther-apy has facilitated the

to a higher level than might have otherwise occurred, that understanding of person and environment interaction,

is, an alteration of the child's regular context could affect Reilly (1962) was the fir-st to apply the constr-ucts of gener-

development , al systems theory and to include the r-ules of hier-archy as

The importance that the EHP framework places on organizing principles. The person and envir-onment ar-e

context is consistent with the emphasis placed on ecology ther-efore viewed as interdependent, interacting through

and context by Auerswald (1971), Auerswald's work on a system of input, output, and feedhack.

ecological epistemology was among the earliest applica- General systems thcor-y and hierarchical stl"Uctures

tions of an ecological perspective to therapeutic interven- provide a framework for the Model of Human Occupation

tion, He argued that the processing of information from a (Kielhofner- & Burke, 1980) The components of the envi-

holistic ecological perspective should replace simpler lin- ronment ar-e identified as objects, per-sons, and events

ear cause-and-effect thinking in therapeutic intervention that again interact with the person in an open system.

He identified a keynote of this kind of ecological thought Kielhofner and Burke included throughput as an element

as the "concern with the context in which a phenomenon of the system that is made up of three hierarchically

occurs" (1971, p. 263), His position was that contextual arranged suhsystems: volition, habituation, and perform-

issues should be considered before any therapeutic inter- ance, Bar-ris (1982) used the framework of the Model of

vention began, Human Occupation to clarify environmental properties

and their- influence on the person.

Occupation science organizes the study of humans

Relevant Occupational Therapy Literature

as occupational beings through the Model of Human Sub-

The environmental psychologists have contributeel to the systems That Influence Occupation (Clark et a!., 1991)

thinking of many occupational therapists, Kiernat (1992) This model, hased on general systems theory, represents

applied the Lawton-Nehamow ecological model in her the per-son as six hierarchically arranged subsystems that

discussion of the environment as a modalitv, Barris inter-act with the environment in an open system,

(1982) drew from the work of Wicker and Hall in her Hmve and Briggs (1982) developed the Ecological

conceptualization of environmental interactions, Howe Systems Model. which uses general systems theory to

and Briggs (1982) descrihed an ecological svstems model portray inter-connections of the per-son and the environ-

for occupational ther-apv that included the theories of ment as concentric circles with the person at the center

Auerswald, Bronfenbrenner, and Wicker, whereas Spen- surrounded hy environmental layers. They detailed the

cer (1991b) used the ideas of HalJ and Lawton in her model's view of function and dysfunction, which consid-

discussion of physical environment and performance, ers both the person and the environmental context,

The terms environment and conlexl are used inter- In defining occupation, Nelson (1988) described the

changeably in the present review, dependent on the word dynamics of occupational form and occupational per-

contained in the original work. Although the occupation- formance within the framework of a system, Occupation-

al therapy literature has most commonly used the term al form was defined as "an objective set of circumstances,

environment, more recent authors have used the term independent of anel external to a person" (p. 633). Nelson

context. The latter ter-m was chosen for the EHP frame- emphasized that performance can only be understooel in

work because context encompasses more of the person's terms of the occupational form. Moreover, occupations

The American Journal 0)' Occupational Therapy 597

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

arc characterized as occurring at different levels. (1993) recommended using a contextual approach to as-

Christiansen (1991) discussed the effect that general sessment so that the assessment is relevant to the person

systems theorv has had on organizing the complex con- and addresses the rerson's wants and needs. Kiernat

cerns involved in occupational therapv. General systems (1990) stated that environment is a factor in disability and

rheory has allowed rhe~e complexiries ro be undersrood muse be conSidered when assessing function. Fisher

while avoiding reductionistic views that oversimplify (1992) advocated for the recognition of occupational

phenomena. therapy's unique perspective of function in the assess-

General systems theory is congruous with the EHP. ment process. She emphasized the imponance of consid-

However, the conceptualization of the EHP is distin- ering the meaningfulness of the measure and placing the

gUished by a nonlinear, dynamic perspective. Dynamic assessment within context. Ethnographic methods have

principles describe systems as multiply determined, com- been proposed as a means of including context in occupa-

plex, and self-organizing (Thelen, 1992). They eschew tional therapy assessment (Spencer, Krefting, & Mat-

schemas and static programs and emphasize variability. tingly, 1993). Proponents of ethnography have suggested

Persons may tend toward certain modes, behaviors, or that these methods can present a more realistic analysis

patterns; however, small changes in the person or con- of the person relative to the expectations within a setting.

text alter these tendencies. Persons self-organize by The current literature has also discussed the applica-

adapting to these changes. When persons are unable to tion of contextual elements. Spencer (1991a) studied the

successfully self-organize, the occupational therapist pro- relationship of social and cultural factors to independent

vides interventions that encompass the complex relation- liVing alternatives. Barney (1991) identified culture as a

ship of the person and his or her context. In dynamic basic contextual determinant when providing services to

systems, hierarchies can exist to suggest patterns but are older adults in need of assisted living.

not requisite pans of the system. In summary, although the occupational therapy lit-

The EHP provides a framework for examining situa- erature has consistently included environment as a salient

tions that occupational therapists encounter every day. feature of performance, no author has proposed a frame-

For example, the framework illustrates why some people work for systematic consideration of environment-

in the intermediate stages of Alzheimer's disease may be context. It is imperative that occurational therapy begin

able to live in a horne environment, whereas others may to directly address the features of context; this knowledge

be more comfortable in a nursing facility (i.e., the sup- will broaden perspectives On successful intervention pos-

ports available to enable the person to function safely at sibilities.

home may be available to the first person, but not to the

second one). The framework also illustrates why nOt all

persons require prevocational training before they can

The EHP Framework

work competitively (i.e., the contextual supportS and

cues available in the actual work: environment may The EHP was developed to provide a framework for inves-

enable the person to perform the work task more con- tigating the relationship between important constructs in

sistently than in simulated task performance, which the practice of occupational therarY: person, context

does not contain these supports). The EHP deciphers the (temporal, rhysical, social, and cultur3l [American Occu-

variance in disruption of daily life that persons expe- rational Therapy Association, in press j), tasks, perform-

rience with disabilitv, illness, or stress from a contextual ance, and therapeutic intervention, to better understand

perspective. the domain of human performance. The primary theo-

Recently, context's significance has received more retical postulate fundamental to the EHP framework is

attention in the occupational therapy literature. Mosey that ecoJogy, or the interaction between person and the

(1992) included context as one of three categories in environment, affects human behavior and performance,

occupational therapy's domain of concern. She classified and that performance cannot be understood outside of

age and environment as the components of context that context.

"provide the persrective from which performance com- The person in this framework includes one's expe-

ponents and occurational areas are viewed relative to the riences and sensorimotor, cognitive, and psychosocial

individual (1992, p. 260). Schkade and Schultz (1992) skills and abilities. The person is represented by a simple

described occu pa tional ada pta tiol1 as a fl'ame of reference stick figure in the circle (see Figure 1). The circle sur-

that gives equal importance to the environment and the rounding the person represents the person's context

person. Occupational adartation is organized by a holis- (physical, temporal, social, and cultural features); the

tic, non hierarchical approach; however, the linear per- only way to see the person is to look through the context.

spective of occupational adaptation distinguishes it from In Figure 1, a wedge has been cut out of the context to

the nonlinear view of the EHP framework. make the person easier to view. The ellipse in the dia-

Several authors have strongly advocated the inclu- gram is the cut edge, enabling the reader to see the

sion of context in occupational therapy assessment. Dunn person. In this model, it is impossible to see the person

598 july 1994, Volume 48, Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

<:ONTEXT TASK

Figure 1. Schemata for the Ecology of Human Performance framework. Persons are embedded in their contexts. An infinite

variety of tasks exists around every person. Performance results when the person interacts with context to engage in tasks.

without first seeing the context. One person might look toward being a downhill skier and

The circles with the Ts inside represent the tasks thar another might look toward being a writer or a cook, but

are available to pecsons. Tasks ace clefined as objective eVCI)'one looks through a context to derive meaning

sets of behaviors necessary to accomplish a goal. Every- about needs or desires.

one has the opportunity or the possibility of performing Occupational therapy also considers a person's life

myriad tasks. PersOns use their skills andabiJities to focus roles Figure 3 illustrates how roles may be characterized

attention on specific tasks from these possibilities. in this model: it displays three roles (cook, mother, and

When persons use their skills and abilities to per- \vife) as a constellation of tasks; some of these roles ovC!'-

form tasb, they use enviconmenta! cues and feature., to lap. Each person who has the roles of Wife, cook, and

sU{lpon performance. Figure 2 iJlustcates a typical person mother includes a unique configuration of tasks in each

embedded in a context sUPDorting regular behaVior, who role as a consequence of her skills and experiences and

has a particular focus on a particular area of perfOl"m~lnce. [he demands of her context. For example, if one person is

For example, a person may notice that the red light is on a gourmet cook, she might have more tasks in the cook

at the street curner, indicating the need to stop. A per- configuration than another person \vho uses a microwave

son's contexts are continuously shifting; as Contexts shift, oven to prepare meals or goes to restaurants.

the behaviors necessary to accomplish a goal a 1.'0 change. The temporal context is also relevant to role charac-

When persons use their context to support pedorm- terization. For example, a child's role as cook might in-

ance, it is like using the lens within the eye to get a vo]ve sim{ller recipes than an adult's. A person who has

perspective on the world. As Figure 2 indicates, the con- sustained an acute injuly, such as a broken leg, may adapt

textual lens interacts with persons' skills and abilities to the role of cook until it is possible to go out to restaurants

enable persons to perform certain tasks The ['esulting again, whet'eas a person with a chronic disability, such as

scope of action is called the performance l-ange (sec Ap- a head injuly, may need to learn comp]etely new cooking

pendL'() Persons view different pOtential tasks through strategies. A person's configuration of the roles is based

their contextual filter, the accumulation of their expe- on the person's skills, abilities, context, and desires.

riences, and their perceptions about the physic31. social, A person may have more limited skills and abilities

and cultural features of their current performance setting. but be embedded in a regular context [hat typically sup-

The American Journal o/OccupCtliOnal Therapy 599

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Figure 2. Schemata of a typical person within the Ecology of Human Periormance framework. Persons use their skills and

abilities to look through the context at the tasks they need or want to do. They derive meaning from this process. Periorm-

ance range is the configuration of tasks that the persons execute.

Figure 3. Illustration of roles in the Ecology of Human Periormance framework. Life roles are a constellation of tasks. Per-

sons have many roles; some tasks fall into more than one role. These role configurations are unique for each person.

600 .lull' 1994, Volume 4/1. Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

pons performance. This person may have the same possi- to get to work, but the person may nor have the skills

ble cues and supports available in the context as that of necessary to use those features to an advantage, so the

the person in Figure 2, but the performance l"angc is performance range is limited. A child may have attention-

narrower because this person does not notice all the cues al defiCits and limited social skills. Although the context

and supports. When a person has a more limited set of for this child has the same cues that it has for every other

skills and abilities, then the person may either derive less child at school, the child who has poor social skill devel-

meaning from the context or may not have the personal opment may not be sensitive to these cues. When the

resources to suppOrt performance (see Figure 4). This teacher frowns, this child may not understand its mean-

person may not have the necessary physical capacities ing, may nor notice, or may misinterpret the frown and

(e.g., a person who is blind may nor be able ro drive), may thus may behave in a way that is viewed as inappropriate

not pick up the cues the context provides (e.g., a child for the context of the school d<lY. Consequently, the per-

may fail to recognize that another child is trying the en- formance range is limited by the inability to take ad-

gage him or her in play), or may not know how to take vantage of thc cues or by the irrelevance of the cues to

advantage of contextual features (e.g., a person may stand the person. When a person has limited skills and abili-

in a full-service lane at the grocery StOl'C with onlv four ties. these limitations can he compounded by inability to

items wlwn an ex[)ress lane is available). Each condition use contextual features to an advantage in suPPOrt of

mal' result in a more limited pCI'formance ['ange. The perfomlance.

wsks that are [)ossible are limited because the person is Sometlmes, thne is a more limited contextual envi-

not able to use the resources that might be available to 1'Onment availahle to the person, but the person pos-

support performance in the context. sesses tvpical skill::; and abilities (see Figure 5). For exam-

For exam pic, if a person is learning to ski, all of the ple, a gourmet cook mav have extensive cooking skills,

contextual features arc available to support skiing but the hut in a kitchen with only a toastel' oven, that cook has

person initially lacks the skills to perform the skiing beha- limited ability to demonstrate those skills and abilities. A

viors and so has a mOl'e limited performance r;l1lge. An skillful downhill skiel' has a difficult time demonsmHing

adult with developmental clisabilities mal' need tl'anspor- those skills in the t!'Opics: the person must travel tu a

tation to work. The bus system is available in the context; more contextually I-elevant 10Guion.

all the features <Ire there to allow persons to use the bus Persons with dis<lbilities sometimes have limited

Figure 4. Schemata of a person with limited skills and abilities within the Ecology of Human Performance framework. Al-

though context is still useful, the person has fewer skills and abilities with which to look through context and derive meaning.

This lack limits the person's performance range.

The American Journal of Occupational iiJerapy 601

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

CD

(f)

~$o

: CD CD T GJ ..

... :.':

,#~ GJ CD T

T GJ CD CD CD

CD CD CD

Figure 5. Schemata of a limited context within the Ecology of Human Performance framework. The person has adequate

skills and abilities, but the context does not provide resources needed to perform. In this situation, performance range is

limited.

skills and abilities and are also in an impoverished context daughter. This new insight helped the occupational

(e.g., a person with severe mental illness who is also therapist redirect therapeutic efforts so that the mother

homeless). They do not have a context that provides and child could play together in a manner that was satiSfy-

them with the salient cues and the objects or events that ing to bOth. By nOt considering context, this occupational

are relevant to them to support pcrformance. Perform- therapist would have put this mother in the difficult situa-

ance of daily life tasks, work, or leisure activities in this tion of having to compromise her relationship with her

situation becomes even more complex. daughter by following the therapist's suggestions. Addi-

tionally, by not considering context, the therapist would

have taken the risk that the child would not make pro-

Therapeutic Intervention Within the EHP

gress because the mOther might not have followed her

Occupational therapy is most effective when it is imhed- suggestions.

ded in real life. If occupational therapists evaluate individ- A naturalistic study by deVries & DeJc:spaul (1989)

ual performance without considering the context of the examined context and the experiences of persons with

performance, there is a great risk of interprcting the be- schizophrenia. They concluded that knowledge of con-

havior inarpropriately. Misinterpretation can lead to in- text provided a new clinical tool. In one example, a man

appropriate choices about therapeutic intervention. For with schizorhrenia was having severe problems with hy-

example, consider an occupational therapist working pertensive illness Clinical investigation to determine the

with a young woman and her daughter, who was physical- cause of his high blood pressure was puzzling. An analysis

ly ready to feed herself. The woman resisted thc occupa- of this man's context revealed that he worked as a dish-

tional therapist's repeated suggestions to use more inde- washer and became extremely anxious when he had to

pendent eating strategies. Upon completing a home visit, sort silverware during the lunch rush. The clinician was

the occupational therapist discovered that the mother able to use this contextual information to convince the

only knew how to intcract with her daughter during meal- employer to change the employee's work tasks. Conse-

time. At other times, the child sat on th~ floor with toys, quently, the man's blood pressure decreased to near

but with no direction or interaction. The horne visit made normal.

it clear to the occupational therapist that the mOther was Eelationships among the EHP framework and the

reluctant to give up her only time of interaction with her variety of interventions available to the occupational

602 July 1994, Volume 48. Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

therapist are shown in Figure 6. Within this framework, play with friends. Adults use these approaches within

therapeutic intervention is a collaboration among the their own lives when they learn a new skill or when they

person, the family, and the occupational therapist direct- work to restore a lost function (e.g., increasing range of

ed at meeting performance needs. Figure 6 displays five motion in a joint after removing a cast).

alternatives for therapeutic intervention; the Appendix Even when the focus of intervention is on skill devel-

contains definitions 0[' each therapeutic intervention. opment, context is still important. For example, Abreu

and Hinojosa (1992) suggested that predictable environ-

ments provide the feedback necessary to correct motor

Establish or Restore

behaViors. Toglia (1992) explained that an understanding

The first therapeutic intervention alternative is to estab- of the interactions of person, task, and environment is

lish or restore (remediate) the person's skills and abili- essential to effective cognitive rehabilitation strategies.

ties. In this category, the occupational therapist identifies

the person's skills and the barriers to performance and

Alter

designs interventions that improve the person's skills and

abilities. The occupational therapist, person, and family The second therapeutic intervention alternative is to alter

might be concerned with reestablishing the person's role the actual context in which persons perform. This inter-

in the family, and so might work on coping skills or phys- vention emphasizes selecting a context that enables the

ical endurance to enable the person to perform tasks person to perform with current skills and abilities. The

related to the family role. Restorative approaches are person can be placed in a different setting that more

common options chosen by therapists, particularly within closely matches his or her current skills and abilities,

the medical model, which considers what is wrong with rather than changing the present setting to accommodate

the person and sets a plan to correct the problem. This the person's needs. The occupational therapist would

approach is adapted, especially with young children, to consider the person's skills, abilities, and difficulties and

include establishing needed skills for function. For exam- find a context that was compatible with this performance

ple, a therapist might work on the muscle tone of a child profile. The important feature of the alter inte[V'ention is

with Down syndrome so that the child can move about to that the therapist does not set out to correct the person

ESTABLISH/ ADAPT

CREATE

RESTORE PREVENT

ALTER

Figure 6. Illustration of therapeutic interventions within the Ecology of Human Performance framework. The arrows indicate

the variables that are affected by each intervention.

The American Journat o/Occupationat Therap)! 603

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

or the environmene; instead, the therapist is looking for that a doctoral student with severe visual impairments

the best match between the person and current contextu- could complete her dissertation.

al features available. Allen (1992) acknowledged the lack

of direction for occupational therapists working with per- Prevenl

sons beyond the acute phase of illness who must live with

functional limitations. Her frame of reference provides The fourth therapeutic intervention option is to prevent

gUidelines for making the best fit for persons with cogni- the occurrence or evolution of maladaptive performance

tive disabilities and available contexts. in context. Sometimes, therapists can predict that certain

Fairweather (1980) used the alter strategy in his negative outcomes are likely unless intervention is pro-

Lodge Society, a community program for persons with vided. Therapists can create interventions to change the

severe meneal illness. He was concerned that persons course of events by addressing person, context, and task

who were able to succeed in jobs at the hospital were variables to enable functional performance to emerge.

unsuccessful at work in the community because of the This view is supported by Coulter (1992) who proposed

intolerance for behavior that was viewed as deviant. One that prevention efforts in mental retardation must take an

strategy was to create janitorial crews that worked at ecological approach that focuses on the interaction be-

times and in settings where their contact with others was tween persons and their environment. Department man-

limited. agers employ a prevention approach when they provide

Another example involves a person who has low as- an orientation for newly hired employees; managers do

sertiveness ability and needs to buy a car. Although the not wait until the employee faces a problem to instruct

therapist could work on assertiveness skill development them in proper procedures. Runners who stretch before

or visit the car dealer to offer some adaptations to the running are employing a prevention approach. Occupa-

process to facilitate the person's purchase, an alternative tional therapists teach persons with spinal cord injuries

that uses the alter interveneion option would be for the how to adjust their position frequenely to prevent con-

therapist to suggest that the person buy a car at a dealer- tractures and decubitus ulcers Therapists also provide

ship that employs the no-haggling approach. Some man- lifting classes in industrial settings to prevent work injur-

ufacturers market their sales strategy as one that mini- ies. Therapists can construct a map of community ser-

mizes the need for assertiveness because there is one vices for a person with severe meneal illness who is mov-

price for their cars and no negotiating is necessary. The ing to a new apartment area to prevent him or her from

therapist does not have to change the context and the feeling socially isolated. Prevention approaches antici-

person can succeed with currene skills to purchase the pate possible and likely problems and change the course

car. of activities to increase positive outcomes. Prevention

approaches are good options for persons with long-term

Adapt conditions that lead to secondary problems; the temporal

context is relevant to these person's outcomes.

The occupational therapist can also adapt the contextual

features and task demands to sUPPOrt performance in

Create

context. When therapists adapt; they design a more sup-

portive context for the person's performance. Therapists The fifth therapeutic intervention option is creating cir-

might enhance some contextual features to proVide cues cumstances that promote more adaptable or complex

and reduce other features to minimize distractibility and performance in context. This therapeutic intervention

make the task more possible for the person. When chil- does not assume that a disability is present or that a

dren are distractible, therapists suggest shorter assign- disability has the potential to interfere with performance.

ments for their seat work in class. When an adult with The person or family seeking assistance may see the

severe disabilities needs to manage the home environ- problem from a functional performance standpoint, not

ment, the therapist might select an environmental con- from a disability standpoint. The therapist participates by

troJ unit. Therapists adjust desk and table configurations providing expertise to enrich contextual and task expe-

to meet individual needs. They might change a desk's riences that will enhance performance. Circumstances

height to match the person's postural support needs or that do not presume disability are constructed; this is

might find a lower table in the dining area for someone what distinguishes the create intervention from the

whose ethnic background suggests preference for a lower prevent intervention, which addresses precluding the

eating surface. Many persons use stick-on notes to help occurrence of a problem that is likely to arise. Early inter-

them remember things they need to do. Persons whose vention programs are common examples of community-

vision is failing may purchase hard-cover novels because based programs that have an enriching philosophy;

they have larger prine than paperbacks. Buning and Hanz- thera pists use their expertise to plan age-appropriate

lik (1993) reported a single-subject study in which the tasks that embellish the young children's development.

person's context was considered in technological adapta- Therapists might also participate in the development of

tions. In this case, computer technologies were used so living communities for elders that provide varied and

604 July 1994, Volume 48, Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

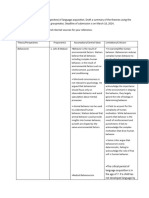

stimulating activities. These community settings do not Table 1

presume their consumers have disabilities. They are de- Case Examples Applying the Ecology of Human

signed to make the best possible use of environment to Performance Framework

enhance living and development. For example, a large Area Addressed Strategy Emp]oyedlInformation

building complex may have many signs to lead visitors CASE 1

and workers to correct locations efficiently, not because Background Mis 15 months old; he has twO older siblings

and both of his parents living in his home, He

there are presumed disabilities, but because signs make has very low muscle tone and a developmental

the environment easier for everyone. When adults play an delay and his family wants him to play and so-

icebreaker game at the beginning of a party they are cialize.

creating an enriched environment for socialization. Establish/Restore The therapist decides to work on M's eye con-

tact and vocalizing as ways for the family to

Occupational therapists have many therapeutic know that M is paying attention to them.

choices with each person they serve, and at each point

Alter The therapist suggests that the family enroll M

along the therapeutic relationship. Therapists often em- in a part-time day care program so he can have

ploy several intervention approaches either simulta- the stimulation of the other children playing as

neously or across time. Table 1 shows two examples of a way to learn play skills,

how an occupational therapist might deal with a person Adapt The therapist talks to the family about moving

the toys closer, having the siblings move closer

and family who need occupational therapy services from when they play with M. The therapist works

all of these approaches. When occupational therapists with the siblings to help them learn how to

include context in the total perspective, it creates possi- change their voice tone so that M can pay at-

tention easier,

bilities; when persons are viewed out of context, viable

options are lost, Prevent The therapist decides to work on functional

communication strategies to prevent M's frus-

tration at socializing, The therapist works with

the family to pick some simple gestures and

Directions for Future Work

sounds that everyone recognizes as communi-

cation signals from M, so he can get some basic

The EHP proposes the relationships among the key varia-

needs met,

bles of person, context, tasks, and performance, Within

Create The therapist and parents discuss the usefulness

the domain of concern of occupational therapy, context is of getting together with other families from the

only relevant as it relates to human performance, church that have similar aged children for a

Mosey (1981) indicated that a frame of reference family gathering, This will be a positive social-

ization expe.-ience for all members, and in-

must describe postulates that allow application to prac- volved M in a typical socialization opportunity.

tice and offer specific guidance for intervention. Scholars

will therefore need to refine these constructs by assessing CASE 2

Background Ms. T is a 75-year-old who has had a right hemi-

their adequacy and answering practice-oriented ques- sphere stroke. She lives with her son and

tions. Several lines of study provide important initial in- daughter-in-law and two grandchildren.

formation that will refine current frames of reference that EstablishiRestore The therapist decides to work on func[\onal

affect occupational therapy, develop new frames of refer- range of motion for reaching and stepping.

ence, and create new assessment and intervention Alter The therapist and Ms, T discuss her need to so-

strategies. cialize and Ms. T expresses concern over her

usual socializing in the quilting club, which ex-

Several questions emerge as fundamental to the in- pects a certain level of performance, The thera-

vestigation of basic relationships proposed in this frame- pist suggests Sunday school as a place to so-

work. A primary question is: How do we capture contex- cialize that doesn't reqUire the fine motor

control.

tual features objectively, and how do we then decide

Adapt The therapist brings clamps to help her with he,-

which features are salient for particular performance situ-

stitching so that she could still do some stitch-

ations' We must also determine how a contextual feature ing, The therapist brings her a stocking darner

becomes relevant for a particular person. There are many and velcro to attach to key items in the bath-

room when she expressed desire to dress and

more contextual features available to persons in a particu-

complete personal hygeine.

lar context than are noticed or used by a person for

Prevent The therapist helps Ms. T to establish a daily

successful performance. In particular performance situa- routine to prevent jOint, muscle, and skin

tions, we need to determine which contextual features breakdowns,

support or create barriers to performance, Are there par- Create The therapist helps her plan regular times to

ticular contextual features that contribute to a person's play with her grandchildren as part of the fam-

ily routine,

resilience'

Occupational therapy assessment strategies also

need to consider context. It will be important to deter- son's performance in the natural context. For example,

mine whether standardized functional assessments are does the dressing item on a standardized test rate the

valid for capturing what is actually known about the per- person the same way that a therapist would rate the

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 605

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

rerson if watching the person's morning dressing rou- cycle, parenting cycle, educational process.

4. Health status: place in continuum of disability, such as

tine This information will enable occupational therapists

' acuteness of injury, chronicity of disability, or terminal

to construct initial data about persons so that planning nature of illness.

can be individualized and relevant to their needs. It will 5 Period: the measurable span of time during which a task

also be important to create new, contextually relevant exists or continues.

assessments in the future, Environment

1. Physical: nonhuman aspects of context (includes the natu-

There are also questions that need to be answered

ral terrain, buildings, furniture, objects, tools, and de-

about the prorosed therapeutic interventions. For exam- vices).

ple, which interventions are the best choices for which 2. Social: availability and expectations of important persons,

performance problems? What is the effect of the pro- such as spouses, friends and caregivers (also includes larg-

posed therapeutic interventions on performance out- er social groups that are influential in establishing norms,

role expectations, and social routines).

comes l What is the difference in functional outcomes

3. Cultural: customs, beliefs, activity patterns, behavior stan-

when therapeutic interventions occur in natural and con- dards, and expectations accepted by the society of which

trived contexts? It is not likely that all the intervention the person is a member (includes political aspects such as

options described here will be equally useful for all per- laws that shape access to resources and affirm personal

formance problems. Therefore, it will be important to test rights; also includes opportunities for education, employ-

ment, and economic support).

the relationships among particular performance prob-

lems and various intervention Options. Therapeutic intervention: A collaboration

The tendency to take ideas created through profes- between the person/family and the occupational

sional dialogue in the literature and regard them as cer- therapist directed at meeting performance needs,

Therapeutic interventions in occupational therapy are multifa-

tainty is tempting; in fact, in dialogue this is easy to do.

ceted and can be designed to accomplish any or all of the

Ideas must be tested, and it seems only fitting that ideas

follOWing.

proposed about context be evaluated in that setting. As Establish/restore a person's abilities to perform in context.

knowledge and understanding grow about the rol<: of Therapeutic intervention can establish or restore person's

context in human performance, these initial proposals abilities to perform in context. This emphasis is on identify-

will need adaptation, a suitable outcome for a set of ideas ing a person's skills and barriers to performance, and deSign-

ing interventions that improve the person's skills and expe-

about ecological relationships .• riences.

Alter actual context in which people perform.

Therapeutic interventions can alter the context within which

Appendix the person performs. This intervention emphasizes selecting

Ecology of Human Performance: Definitions a context that enables the person to perform with current

skills and abilities. This can include placing the person in a

Person: An individual with a unique configuration

different setting that more closely matches current skills and

of abilities, experiences, and sensorimotor, abilities, rather than changing the present setting to accom-

cognitive, and psychosocial skills. modate needs.

A. Persons are unique and complex and therefore precise Adapt contextual features and task demands so they support

predictability about their performance is impossible. performance in context.

B. The meaning a person attaches to task and contextual Therapeutic interventions can adapt contextual features and

variables strongly influences performance. task demands so they are more supportive to the person's

Task: An objective set of behaviors necessary to performance. In this intervention, the therapist changes as-

accomplish a goal. pects of context and/or tasks so performance is more possi-

A. An infinate variety of tasks exists around every person. ble. This can include enhancing some features to provide

B. Constellations of tasks form a person's roles. cues, or reducing other features to ret.luce distractibility.

Prevent the occurrence or evolution of malpractice perform-

Performance: Both the process and the result of

ance in context.

the person interacting with context to engage in Therapeutic interventions can prevent the occurrence or

tasks. evolution of barriers to performance in context. Sometimes,

A. The performance range IS detennined by the interaction therapists can predict that certain negative outcomes are

between the person and the context. likely without intervention to change the course of events.

B. Performance in natural contexts is different from perform- Therapists can create intervention to change the course of

ance in contrived contexts (ecological validity, Bronfen- events. Therapists can create interventions that address per-

brenner, 1979). son, context, and task variables to change the course, thus

Context: (Adapted from The AOTA Uniform enabling functional performance to emerge.

Terminology Definition [3rd edition] for context) Create circumstances that promote more adaptable!complex

performance in context.

is as follows: Therapeutic interventions can create circumstances which

Temporal A::,pects (note: although temporal aspects are deter-

promote more adaptable performance in context. This

mined by the person, they become contextual due to the social

therapeutiC intervention does not assume a disability is pre-

and cultural meaning attached to the temporal features)

sent or has the potential to interfere with performance. This

1. Chronological: person's age

therapeutic choice focuses on proViding enriched contexual

2. Developmental: stage or phase of maturation.

and task experiences that will enhance performance.

3. Life cycle: place in important life phases, such as career

606 Jul)! 1994, Volume 48, Number 7

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

References model for occupational therapy, AmericClnjournal ofOccupa-

Abreu, B. C, & Hinojosa, J. (1992). The process approach tional Tberapy, 36, 322-327

for cognitive-perceprual and postural control dysfunction for Kielhofner, G" & Burke, .I P. (1980), A model of human

adults with brain injuries. In N. Katz (Ed.), Cognitive rebabilila- occupation, Pan 1. Conceptual framework and content. Ameri-

lion. Models for inlervenlion in occupalional tberapy (pp. can journal of Occupational Therapy, 34, 572-581.

167-194). Stoneham, MA: Andover Ivledical. Kiernat,J M, (1990), Considering the environment. In C. B.

. Allen, D. K. (1992). Occupationaltbempy treatment goals Royeen (Ed,), AOTA Self Study Series: Assessing jimction (Les-

.lor the physically and cognitive~y disabled. Rockville, MD: son 6). Rockville, MD: American Occupational Therapy

American Occupational Therapy Association. Association,

American Occupational Therapy Association. (in press). Kiernat, .I M. (1992). Environment: The hidden modality.

Uniform terminology for occupational therapy- third edition. JournaL of Physical and Occupational Therapy in Ceriatrics,

American Journal o( Occupational Therapy 21, 3-12

Auerswald, E H. (1971) Families, change, and the ecologi- King, L. J, (1978). Toward a science of adaptive responses.

cal perspective. Family Process, 10, 263-280. Amedcan joumal of Occupational Tberapy, 32, 429-437.

Barney, K. F. (991). From Ellis island to assisted living: Lawton, M, P, (1982). Competence. environmental press,

Meeting the needs of older adults from diverse culrures. Ameri- and the adaptation of older reople. In M. P. Lawton, P. G.

can journal of Occupational Therapy. 45, 486-593. Windley, & T. 0, Byens (Eds.), Aging and the enuironment (pp,

Barris, R. (1982). Environmental interactions: An extension 33-59). New York Springel'

of the model of occupation. American journal ofOccupation- Llorens, L. A, (1970). Facilitating growth and develorment

al Therapy, 36, 637-644 The rromise of occupational therapy, American journal o(

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology o(buman devel- Occupational Tberapv, 24, 93-101.

opment Cambridge, j\1.A: Harvard University Press. Mosey, A. C. (1981) Occupational therapY' Con(iguration

Bruner, J (1989). Acls o( meaning Ca;11bridge, ivlA Har- o( a proFession. New York: Raven.

vard University Press. Mosey, A, C. (1992). Applied scientific inquiry in the health

Buning, M. E., & Hanzlik,). R. (1993). Adaptive computer professions: An epistemological orientation, Rockville: Ameri-

use for a rerson with visual impairment. American journal o( can Occupational Therapy Association,

Occupational Therapy, 47, 998-1007 Murray, H, A. (1938), E.xplorations in personality New

York: Oxford, .

Christiansen, C. (1991). Occupational therapy: Intel-ven-

tion for life rerfonnance. In C. ChriStiansen & C. Baum (Eds.), Nelson, D, L. (1988). Occupation: Form and performance,

Occupalional therapy: OIJercoming human performance defi- American journal 0/ Occupational Therapy. 42, 633-641,

cits (rr. 3-44). New York: McGraw-HilI. Reilly, M, (1962). Occupational therapy can be one of [he

Clark, F. A, Parham, D., Carlson, Iv\. E, Frank. G.,Jackson, great ideas of 20th century medicine, American journal 0)'

J, Pierce, D, Wolfe, R. .I, & Zemke, R. (991) Occupational Occupational Therapy. 16. 1-9,

science: Academic innovation in the service of occupational Schkade, J, K., & Schultz, S. (1992). Occupational adapta-

therapy's furure. American joumal o( Occupational Thempy, tion: Toward a holistic approach for contemrorary practice.

45, 300-310, Part 1 American journal o( Occupational Therapy. 46,

Coulter, D. L. (1992), An ecolog)f of prevention for the 829-837

future. J\!le11lal Retardation, 30, 363-369, Srencer. J C. (1991a). An ethnogl-aphic study of inde-

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psycholof!,): o( opti- pendent living alternatives, American jou rnal o( Occupational

mal experience. New York: Harper Perennial. Therapy, 45, 243-251.

deWies, M. W" & Delespaul, P A E. G (1989) Time, Spencer, J. C. (1991b). The physical environment and per-

context, and subjective experiences in schizophrenia, Schizo- formance In C. Christiansen & C. Baum (Eds.), Occupational

phrenia Bulletin. 15, 233-244, tberapl" OIJercoming human performance de/i'cils (pp.

Dunn, W. (1993). The Issue Is-Measurement of function: 12')-140). New York: Slack,

Actions for the future, American joumal o( Occupational Spencer. J., Krefting, L., & jv1attingly, C. (1993), Incorpora-

Therapy, 47. 3')7-3')9 tion of ethnographic methods in occupational therapy assess-

ment. American journal 0/ Occupational Therapy, 47,

Fairweather, G, W, (1980) The prototype lodge societ)':

Instituting group process principles, New Directions/or }llental 303-309

Health Services, 7. 13-32. Thelen. E. (1992), Developmel1l as a dynamic system. Cur-

Fidler, G S, & Fidler, F. W. (1978). Doing and becoming rent Directions in PS1Jchological Science, I, 189-193,

Purposeful action and self actualization, American joumal 0/ TogJia,j. P. (1992). A dynamical approach to cognitive reha-

Occupational Therapy, 32, 305-310, bilitation, In N. Katz (Ed), Cogniliue rebabilitalion, Models(or

Fisher, A. (1992). Functional measure, Pan 1: What is func- intervention in occupational therapv (pp, 104-143), Stone-

tion, what should we measure. and how should we measure it" ham, J\rlA: Andover Medical.

Americanjoumal o( Occupational Therapl', 46, 183-185, Wicker, A. W (1979), An introduction to ecological pS1J-

Gibson, j. J. (1986). An ecological approach 10 visual per- cbology Camhridge, J\rlA: Cambridge University Press

ception. I-lilklale, NJ: Erlbaum. Wensch.J, v (985). V)lgotskyandlhesocialformationo)'

Hall, E T. (1983) The dance o(/i(e. New York Doubleday. mind Cambridge, MA: Halvard University Press,

Han, R. (1979). Children's experience o(place, New York: Vygotsky, L. S (1978). i\Jlind in society: The development o(

Irvington, higher psychological processes Cambridge, MA: Harvard Uni-

Holahan, C. J (1986), Environmental psychology, Annual versity Press,

Review of Psychologv, .)7, 381-407 Zerubavel, E, (1981). Hidden rb)ltbms Scbedules and cal-

Howe, M, c., & Briggs, A. K. (1982), Ecological sysrems endars in social Ii/e, Berkeley: Uni~ersitv of California Press.

The American ./oumal 0/ Occupational Tberapy 607

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/pdfaccess.ashx?url=/data/journals/ajot/930225/ on 02/28/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- OTB 502 Syllabus 2019Dokument22 SeitenOTB 502 Syllabus 2019Gehan BotorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mentally Retarded Child: Essays Based on a Study of the Peculiarities of the Higher Nervous Functioning of Child-OligophrenicsVon EverandThe Mentally Retarded Child: Essays Based on a Study of the Peculiarities of the Higher Nervous Functioning of Child-OligophrenicsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Filipino Folk Music - World Federation of Music TherapyDokument8 SeitenFilipino Folk Music - World Federation of Music Therapyelka prielaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Icf ModelDokument10 SeitenWho Icf ModelXulkanain ZENoch keine Bewertungen

- The Application of Assessment and Evaluation Procedure in Using Occupation Centered PracticeDokument55 SeitenThe Application of Assessment and Evaluation Procedure in Using Occupation Centered PracticeAswathi100% (2)

- Logical Fallacies and Fallacious AppealsDokument1 SeiteLogical Fallacies and Fallacious AppealsEllen LamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Occupational Brain A Theory of Human NatureDokument6 SeitenThe Occupational Brain A Theory of Human NatureJoaquin OlivaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupational Therapy in Pain ManagementDokument26 SeitenOccupational Therapy in Pain ManagementNoor Emellia JamaludinNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of OT Infographic TimelineDokument1 SeiteHistory of OT Infographic TimelineAddissa MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational PerformanceDokument23 SeitenCognition, Cognitive Rehabilitation, and Occupational PerformanceMaria AiramNoch keine Bewertungen

- B. Occupational Therapy (Hons.) : Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Teknologi MaraDokument3 SeitenB. Occupational Therapy (Hons.) : Faculty of Health Sciences Universiti Teknologi MaraSiti Nur Hafidzoh OmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Therapy As An Anti-Oppressive Practice: The Arts in PsychotherapyDokument5 SeitenMusic Therapy As An Anti-Oppressive Practice: The Arts in PsychotherapymeytiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MOHOST InformationDokument1 SeiteMOHOST InformationRichard FullertonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rehab of Patients With HemiplegiaDokument2 SeitenRehab of Patients With HemiplegiaMilijana D. DelevićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupational AdaptationDokument5 SeitenOccupational AdaptationVASH12345100% (1)

- Occupational TherapyDokument11 SeitenOccupational TherapyYingVuong100% (1)

- Foundation in Occupational Therapy 2: Model of Human OccupationDokument21 SeitenFoundation in Occupational Therapy 2: Model of Human OccupationDEVORAH CARUZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Program ProposalDokument17 SeitenProgram Proposalapi-582621575Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kawa Made Easy 2015Dokument16 SeitenKawa Made Easy 2015Kaylee2302Noch keine Bewertungen

- PANat - Thetrical - Air Splints - Talas Pneumaticas Margaret JohnstoneDokument44 SeitenPANat - Thetrical - Air Splints - Talas Pneumaticas Margaret JohnstonePedro GouveiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Working As An Occupational Therapist in Another Country 2015Dokument101 SeitenWorking As An Occupational Therapist in Another Country 2015RLedgerdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holism Vs ReductionismDokument38 SeitenHolism Vs ReductionismJudy Ann TumaraoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mosey's Developmental GroupsDokument3 SeitenMosey's Developmental Groupsedwin.roc523100% (2)

- Occupation in Occupational Therapy PDFDokument26 SeitenOccupation in Occupational Therapy PDFa_tobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and EngagementDokument16 SeitenThe Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagementalepati29Noch keine Bewertungen

- Body Awareness FactsheetDokument2 SeitenBody Awareness FactsheetDr.GladsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Immobilization Protocol For Extensor Tendon RepairDokument2 SeitenImmobilization Protocol For Extensor Tendon RepairFatin NawarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dysphagia in Huntington'sDokument5 SeitenDysphagia in Huntington'sDani PiñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essentials of Music Therapy Assessment 141221Dokument643 SeitenEssentials of Music Therapy Assessment 141221Rizzo RizNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Appraisal of How Occupational Therapists Can Enable Participation in Adaptive Physical Activity For Children and Young PeopleDokument9 SeitenA Critical Appraisal of How Occupational Therapists Can Enable Participation in Adaptive Physical Activity For Children and Young PeopleNatalia RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erik EriksonDokument17 SeitenErik Eriksonrebela29Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pope'S Biography: Garcia, Marianne Faye N. FCL 602 The Perpetualite: A Minister of Life BSOT-3 Mr. John ValenzuelaDokument2 SeitenPope'S Biography: Garcia, Marianne Faye N. FCL 602 The Perpetualite: A Minister of Life BSOT-3 Mr. John ValenzuelaMarianne GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is The International Classification of FunctioningDokument1 SeiteWhat Is The International Classification of FunctioningCare InvalidsNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Case Study On Task Oriented ApproachDokument48 SeitenA Case Study On Task Oriented ApproachTIMOTHY NYONGESA0% (1)

- Occupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process Fourth EditionDokument87 SeitenOccupational Therapy Practice Framework: Domain and Process Fourth EditionDanielle CakeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aota PDFDokument2 SeitenAota PDFJuliana MassariolliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of HandDokument76 SeitenAssessment of Handchirag0% (1)

- Frame of ReferenceDokument10 SeitenFrame of ReferenceGustavo CabanasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asi ReportsDokument24 SeitenAsi Reportsjdgohil1961Noch keine Bewertungen

- Client-Centered AssessmentDokument4 SeitenClient-Centered AssessmentHon “Issac” KinHoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For Documentation of Occupational Therapy PDFDokument7 SeitenGuidelines For Documentation of Occupational Therapy PDFMaria AiramNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Gestalt PsychologyDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Gestalt PsychologyFarhad Ali MomandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part 2: Social Skills Training: RatingDokument3 SeitenPart 2: Social Skills Training: RatingGina GucioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurodevelopmental Treatment Approaches For Children With Cerebral PalsyDokument24 SeitenNeurodevelopmental Treatment Approaches For Children With Cerebral PalsyDaniela NevesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Horak 2006 Postural Orientation and EquilDokument5 SeitenHorak 2006 Postural Orientation and EquilthisisanubisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PRDokument11 SeitenWilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PRIsabel PereiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- DyslexiaDokument19 SeitenDyslexiaJubie MathewNoch keine Bewertungen

- TIA Stroke PathwayDokument2 SeitenTIA Stroke Pathwaywenda sariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitDokument11 SeitenVergara, J. - T.O. in The Neonatal Intensive Care UnitFedora Margarita Santander CeronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupational Therapy and Physical DysfunctionDokument11 SeitenOccupational Therapy and Physical DysfunctionM Burghal100% (2)

- Types of DisabilityDokument2 SeitenTypes of DisabilityUmraz BabarNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Ot PedsDokument2 SeitenWhat Is Ot Pedsapi-232349586Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Biomechanical ModelDokument17 SeitenThe Biomechanical ModelLama NammouraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bird T. Baldwin: A Holistic Scientist in Occupational Therapy's HistoryDokument4 SeitenBird T. Baldwin: A Holistic Scientist in Occupational Therapy's HistoryAymen DabboussiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ashley M Occt 651 Occupational ProfileDokument11 SeitenAshley M Occt 651 Occupational Profileapi-25080062950% (2)

- The Bobath Concept inDokument12 SeitenThe Bobath Concept inCedricFernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promoting Strengths in Children and YouthDokument2 SeitenPromoting Strengths in Children and YouthThe American Occupational Therapy AssociationNoch keine Bewertungen

- HumanDokument18 SeitenHumanVanessa Mae EncarnadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TheoriesDokument4 SeitenTheoriesBats AmingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Embedding Change in Deep Levels of CultureDokument6 SeitenEmbedding Change in Deep Levels of CultureShi Kham100% (1)

- Ethics For UpscDokument3 SeitenEthics For UpscRuchira ThotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abhava and Anupalabdhi IIJDokument10 SeitenAbhava and Anupalabdhi IIJvasubandhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mark D. Forman - A Guide To Integral Psychotherapy - Complexity, Integration, and Spirituality in Practice-State University of New York Press (2010)Dokument347 SeitenMark D. Forman - A Guide To Integral Psychotherapy - Complexity, Integration, and Spirituality in Practice-State University of New York Press (2010)Maureen100% (2)

- Material of Fact and OpinionDokument4 SeitenMaterial of Fact and OpinionKhairuna PohanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soc Sci 121-Pag Unawa Sa Sarli Understanding The Self: Arlyn R. Dimaano, LPT Instructor I Mindoro State UniversityDokument30 SeitenSoc Sci 121-Pag Unawa Sa Sarli Understanding The Self: Arlyn R. Dimaano, LPT Instructor I Mindoro State UniversityDaniel PedrazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kant's TheoryDokument23 SeitenKant's TheoryHannah Joy RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theodore Roszak - Where The Wasteland Ends - Politics and Transcendence in Postindustrial Society PDFDokument484 SeitenTheodore Roszak - Where The Wasteland Ends - Politics and Transcendence in Postindustrial Society PDFIrvin Smith100% (3)

- Who Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryDokument15 SeitenWho Am I? The Self/Subject According To Psychoanalytic TheoryAna IrimiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- P4 Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDokument31 SeitenP4 Human Person As An Embodied SpiritAnne MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 1 Psychoanalysis, Psychodynamic and Psychotherapy: StructureDokument54 SeitenUnit 1 Psychoanalysis, Psychodynamic and Psychotherapy: StructureAmal P JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 6 - Attribution ProcessDokument6 SeitenChapter 6 - Attribution ProcessIsro' fajar roslinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy As A Field Study (Continuation)Dokument38 SeitenPhilosophy As A Field Study (Continuation)Bryan DionesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACT D Therapist Manual PDFDokument132 SeitenACT D Therapist Manual PDFedw68Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle'S Elusive Summum Bonum: Flourishing. Aristotle Brings To This Topic A Mind Unsurpassed in The DepthDokument19 SeitenAristotle'S Elusive Summum Bonum: Flourishing. Aristotle Brings To This Topic A Mind Unsurpassed in The Depthtext7textNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Practice Truth Initiations - Final PDFDokument46 Seiten7 Practice Truth Initiations - Final PDFLawrence W Spearman100% (1)

- DC Schindler The Universality of ReasonDokument23 SeitenDC Schindler The Universality of ReasonAlexandra DaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- STS ReviewerDokument4 SeitenSTS Reviewerjuju on the beatNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Edinburgh Philosophical Guides Series) Large, William - Heidegger, Martin-Heidegger's Being and Time - An Edinbrugh Philosophical Guide-Edinburgh University Press (2008)Dokument161 Seiten(Edinburgh Philosophical Guides Series) Large, William - Heidegger, Martin-Heidegger's Being and Time - An Edinbrugh Philosophical Guide-Edinburgh University Press (2008)Davor Katunarić100% (1)

- Your Invisible PowerDokument58 SeitenYour Invisible PowerIsis Witten100% (2)

- Aquinas EpistemologyDokument25 SeitenAquinas EpistemologyQuidam RV100% (1)

- Still Better Never To Have Been: A Reply To (More Of) My Critics - David BenatarDokument31 SeitenStill Better Never To Have Been: A Reply To (More Of) My Critics - David BenatarAnonymous oyXvKN4OK100% (3)

- What Is EthicsDokument12 SeitenWhat Is EthicsNakyanzi AngellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tim Ingold - On The Distinction Between Evolution and History PDFDokument20 SeitenTim Ingold - On The Distinction Between Evolution and History PDFtomasfeza5210Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hervey, Lenore Wadsworth - Artistic Inquiry in Dance - Movement Therapy - Creative Research Alternatives-Charles C. Thomas (2000) PDFDokument175 SeitenHervey, Lenore Wadsworth - Artistic Inquiry in Dance - Movement Therapy - Creative Research Alternatives-Charles C. Thomas (2000) PDFSiyao LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discipline and Ideas in The Social Sciences Week 1, Quarter 2Dokument5 SeitenDiscipline and Ideas in The Social Sciences Week 1, Quarter 2Jennie KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH2 - Reviewed-33 (PRF)Dokument34 SeitenCH2 - Reviewed-33 (PRF)atikah nabilahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neville Goddard - FundamentalsDokument3 SeitenNeville Goddard - FundamentalsRafael Ehud Zaira75% (4)

- Stoicism Today - Selected Writin - Patrick UssherDokument185 SeitenStoicism Today - Selected Writin - Patrick Ussherleviticus100% (1)

- (Frontiers of Narrative) David Herman - The Emergence of Mind - Representations of Consciousness in Narrative Discourse in English (2011, University of Nebraska Press)Dokument326 Seiten(Frontiers of Narrative) David Herman - The Emergence of Mind - Representations of Consciousness in Narrative Discourse in English (2011, University of Nebraska Press)DjaballahANoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture One Classical Criticism PlatoDokument7 SeitenLecture One Classical Criticism PlatoJana WaelNoch keine Bewertungen