Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

De Gilliaco v. Manila Railroad (1955)

Hochgeladen von

Ymil Rjiv DT MatbaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

De Gilliaco v. Manila Railroad (1955)

Hochgeladen von

Ymil Rjiv DT MatbaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

De Gilliaco et al. v. Manila Railroad Company G.R. No.

L-8034

18 November 1955 J. JBL Reyes

TOPIC IN SYLLABUS: Common Carriage of Passengers Responsibility for acts of employees

SUMMARY: Lt. Gilliaco boarded a train. Devesa had a grudge against Gilliaco, and happened to

be a train guard, armed with a company-issued carbine, for Manila railroad. When they met in

the train, Devesa shot Gilliaco to death. The CFI granted the widow’s claim for damages against

Manila Railroad on the ground that a contract of transportation implies protection of the

passengers against acts of personal violence by the agents or employees of the carrier.

The Supreme Court reversed, stating that this responsibility extends only to those that the

carrier could foresee or avoid through the exercise of the degree of care and diligence required

of it. It also noted that Devesa was under no obligation to safeguard the passengers of the

Calamba-Manila train, where the deceased was riding; and the killing of Gillaco was not done in

line of duty.

CASE HISTORY: CFI Laguna sentenced Manila Railroad to pay De Gillaco P4,000.00 as

damages. The Supreme Court reverses and dismisses the complaint.

FACTS: Name of deceased: Lt. Tomas Gillaco, husband of herein plaintiff, boarded a train.

When, Where: 7:30 am, April ’46, Calamba to Manila leg, (second leg is Manila to La Union.)

As fate would have it: When the train reached Paco Railroad station, Emilio Devesa, a train

guard of the Manila Railroad Company, happened to be in the said station waiting for the

same train which would take him to Tutuban Station.

Homicide at the train coach: Devesa had a long standing grudge with Gillaco, dating back to

the Japanese Occupation. Using the company-issued carbine, Devesa shot Gillaco. He was

convicted of homicide by final judgment of the Court of Appeals.

Manila Railroad’s Contention: no liability attaches to it as employer of the killer, Emilio

Devesa; that it is not responsible subsidiary ex delicto, under Art. 103 of the Revised Penal

Code, because the crime was not committed while the slayer was in the actual performance of

his ordinary duties and service; nor is it responsible ex contractu, since the complaint did not

aver sufficient facts to establish such liability, and no negligence on appellant's part was shown.

CFI Laguna: The Railroad Company is responsible on the ground that a contract of

transportation implies protection of the passengers against acts of personal violence by the

agents or employees of the carrier.

ISSUE: Is Manila Railroad responsible for the death of Lt. Gillaco? NO.

Supreme Court: There can be no quarrel with the principle that a passenger is entitled to

protection from personal violence by the carrier or its agents or employees, since the contract of

transportation obligates the carrier to transport a passenger safely to his destination. But under

the law of the case, this responsibility extends only to those that the carrier could foresee or

avoid through the exercise of the degree of care and diligence required of it.

Citing Lasam v. Smith: by entering into that contract he bound himself to carry the plaintiff

safely and securely to their destination; and that having failed to do so he is liable in damages

unless he shows that the failure to fulfill his obligation was due to causes mentioned in article

1105 of the Civil Code, which reads as follows:

Bruce Wayne CASE #74

"No one shall be liable for events which could not be foreseen or which, even if foreseen, were

inevitable, with the exception of the cases in which the law expressly provides otherwise and

those in which the obligation itself imposes such liability.”

Application: The act of guard Devesa in shooting passenger Gillaco (because of a personal

grudge nurtured against the latter since the Japanese occupation) was entirely unforseeable by

the Manila Railroad Co. The latter had no means to ascertain or anticipate that the two would

meet, nor could it reasonably foresee every personal rancor that might exist between each one

of its many employees and any one of the thousands of eventual passengers riding in its trains.

The shooting in question was therefore "caso fortuito" within the definition of article 1105 of the

old Civil Code, being both unforeseeable and inevitable under the given circumstances; and

pursuant to established doctrine, the resulting breach of appellant's contract of safe carriage

with the late Tomas Gillaco was excused thereby.

Note: The lower Court and the appellees both relied on the American authorities that

particularly hold carriers to be insurers of the safety of their passengers against willful assault

and intentional illtreatment on the part of their servants, it being immaterial that the act should

be one of private retribution on the part of the servant, impelled by personal malice toward the

passenger But as can be inferred from the previous jurisprudence of this Court, the Civil Code

of 1889 did not impose such absolute liability. The liability of a carrier as an insurer was not

recognized in this jurisdiction.

Another important consideration1: When the crime took place, the guard Devesa had no

duties to discharge in connection with the transportation of the deceased from Calamba to

Manila. The stipulation of facts is clear that when Devesa shot and killed Gillaco, Devesa was

assigned to guard the Manila-San Fernando (La Union) trains, and he was at Paco Station

awaiting transportation to Tutuban, the starting point of the train that he was engaged to guard.

In fact, his tour of duty was to start at 9:00 a.m., two hours after the commission of the crime.

Devesa was therefore under no obligation to safeguard the passengers of the Calamba-Manila

train, where the deceased was riding; and the killing of Gillaco was not done in line of duty. The

position of Devesa at the time was that of another would be passenger, a stranger also awaiting

transportation, and not that of an employee assigned to discharge any of the duties that the

Railroad had assumed by its contract with the deceased. As a result, Devesa's assault cannot

be deemed in law a breach of Gillaco's contract of transportation by a servant or employee of

the carrier.

1

Quoted the Supreme Court of Texas, as persuasive source, in Houston and TCR Co. v. Bush: The only good

reason for making the carrier responsible for the misconduct of the servant perpetrated in his own interest, and not in

that of his employer, or otherwise within the scope of his employment, is that the servant is clothed with the delegated

authority, and charged with the duty by the carrier, to execute his undertaking with the passenger. And it cannot be

said, we think, that there is any such delegation to the employees at a station with reference to passengers

embarking at another or traveling on the train.

Bruce Wayne CASE #74

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- de Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad Company, GR No. L-8034, November 18, 1955Dokument3 Seitende Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad Company, GR No. L-8034, November 18, 1955Zyrene CabaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gillaco v. Manila RailroadDokument4 SeitenGillaco v. Manila RailroadHaniyyah FtmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gillaco vs. Manila RailroadDokument3 SeitenGillaco vs. Manila RailroadStephanie Reyes GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad Company, G.R. No. L-8034, Nov. 18, 1955Dokument2 SeitenDe Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad Company, G.R. No. L-8034, Nov. 18, 1955Vincent BernardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Gillaco Et Al V Manila Railroad CompanyDokument2 SeitenDe Gillaco Et Al V Manila Railroad CompanymodernelizabennetNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad CompanyDokument7 SeitenDe Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad CompanyMaria LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad CompanyDokument1 SeiteDe Gillaco vs. Manila Railroad CompanyTin NavarroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan vs. Perez, 20 SCRA 412, No. L-22272 June 26, 1967Dokument3 SeitenMaranan vs. Perez, 20 SCRA 412, No. L-22272 June 26, 1967Daysel FateNoch keine Bewertungen

- De Gillaco v. MRRDokument1 SeiteDe Gillaco v. MRRAndrew PaulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan v. PerezDokument6 SeitenMaranan v. PerezLorelei B RecuencoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan Vs PerezDokument2 SeitenMaranan Vs PerezLance MorilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court: Pedro Panganiban For Plaintiff-Appellant. Magno T. Bueser For Defendant-AppellantDokument4 SeitenSupreme Court: Pedro Panganiban For Plaintiff-Appellant. Magno T. Bueser For Defendant-Appellantcg__95Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gillaco, Et Al vs. Manila Railroad CompanyDokument1 SeiteGillaco, Et Al vs. Manila Railroad Companytoni_mlpNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 LRTA V NavidadDokument2 Seiten5 LRTA V NavidadPaula VallesteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan vs. PereDokument3 SeitenMaranan vs. PereStephanie Reyes GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oblicon Cases 1Dokument15 SeitenOblicon Cases 1Lynx LycanNoch keine Bewertungen

- JOSE CANGCO vs. MANILA RAILROAD CODokument3 SeitenJOSE CANGCO vs. MANILA RAILROAD COhannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law Case Digest Congco v. MRC 1912Dokument3 SeitenLaw Case Digest Congco v. MRC 1912Jerus Samuel BlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan vs. PerezDokument2 SeitenMaranan vs. PerezYodh Jamin OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 122039 May 31, 2000 VICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsDokument56 SeitenG.R. No. 122039 May 31, 2000 VICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsJayson AbabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maranan Vs PerezDokument2 SeitenMaranan Vs PerezMaefel GadainganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalas vs. CA (2000) Pamisa EH202Dokument4 SeitenCalalas vs. CA (2000) Pamisa EH202Hyules PamisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT AUTHORITY & RODOLFO ROMAN vs. MARJORIE NAVIDADDokument2 SeitenLIGHT RAIL TRANSIT AUTHORITY & RODOLFO ROMAN vs. MARJORIE NAVIDADCharles Roger RayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Landingin Vs PaTranCoDokument3 SeitenLandingin Vs PaTranCoJonah BucoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Collated) DAY THREE FinalDokument13 Seiten(Collated) DAY THREE FinalMatthew WittNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transportation Law Case Digest: Maranan V. PerezDokument3 SeitenTransportation Law Case Digest: Maranan V. PerezQueenie QuerubinNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. L-22272 June 26, 1967 Antonia MARANAN, Plaintiff-Appellant, Pascual Perez, ET AL., Defendants. PASCUAL PEREZ, Defendant AppellantDokument4 SeitenG.R. No. L-22272 June 26, 1967 Antonia MARANAN, Plaintiff-Appellant, Pascual Perez, ET AL., Defendants. PASCUAL PEREZ, Defendant AppellantBer Sib JosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11 Cangco V Manila RailroadDokument3 Seiten11 Cangco V Manila RailroadluigimanzanaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- 31 Cangco V Manila RailroadDokument3 Seiten31 Cangco V Manila RailroadluigimanzanaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- VICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsDokument4 SeitenVICENTE CALALAS, Petitioner, Court of Appeals, Eliza Jujeurche Sunga and Francisco Salva, RespondentsAnonymous oDPxEkdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts and Damages CompilationDokument66 SeitenTorts and Damages CompilationAJ SaavedraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CALALAS Vs CADokument2 SeitenCALALAS Vs CABeatrice AbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- LRTA V NatividadDokument2 SeitenLRTA V NatividadMary Grace G. EscabelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts 1Dokument49 SeitenTorts 1GM AlfonsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plaintiff-Appellant Defendant-Appellee Ramon Sotelo, Kincaid & HartiganDokument11 SeitenPlaintiff-Appellant Defendant-Appellee Ramon Sotelo, Kincaid & Hartigananika fierroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cangco V Manila RailroadDokument3 SeitenCangco V Manila RailroadAsia Wy100% (1)

- Transportation Law2Dokument23 SeitenTransportation Law2Dairen RoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9 Cangco v. Manila Railroad Co.20180402-1159-1d8hh9tDokument10 Seiten9 Cangco v. Manila Railroad Co.20180402-1159-1d8hh9tM GNoch keine Bewertungen

- GV Florida Transport Inc V Heirs of Romeo L Battung Jr.Dokument2 SeitenGV Florida Transport Inc V Heirs of Romeo L Battung Jr.Niajhan PalattaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Estrelita Bascos v. CA and Rodolfo Cipriano FactsDokument18 SeitenEstrelita Bascos v. CA and Rodolfo Cipriano FactsKel SarmientoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LRTA v. Navidad, G.R. No. 145804, 6 February 2003Dokument3 SeitenLRTA v. Navidad, G.R. No. 145804, 6 February 2003RENGIE GALO0% (1)

- Calalas vs. Court of Appeals, 332 SCRA 356, May 31, 2000Dokument6 SeitenCalalas vs. Court of Appeals, 332 SCRA 356, May 31, 2000RaffyLaguesmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline 2 Continuation'Dokument9 SeitenOutline 2 Continuation'Carla January OngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corliss v. Manila Railroad Co. Case DigestDokument2 SeitenCorliss v. Manila Railroad Co. Case DigestSittyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rakes Vs Atlantic Gulf and Pacific Co.Dokument4 SeitenRakes Vs Atlantic Gulf and Pacific Co.Ogie Rose BanasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 Lrta v. NavidadDokument2 Seiten03 Lrta v. NavidadRachelle GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalas v. CADokument2 SeitenCalalas v. CAAlfonso Miguel Dimla100% (1)

- Transportation Law NotesDokument25 SeitenTransportation Law NotesNovern Irish PascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feb 1 DigestsDokument15 SeitenFeb 1 DigestsMartee BaldonadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalas Vs CA Sunga SalvaDokument5 SeitenCalalas Vs CA Sunga SalvaAkimah KIMKIM AnginNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases 10-12Dokument6 SeitenCases 10-12hannahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cango V Manila RoadDokument1 SeiteCango V Manila RoadVincent BernardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calalas Vs CA GR 91189Dokument3 SeitenCalalas Vs CA GR 91189maribelsumayangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Light Rail Transit AuthorityDokument13 SeitenLight Rail Transit AuthorityJek SullanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2.LRTA v. NavidadDokument3 Seiten2.LRTA v. NavidadJared LibiranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transpo Law Case DoctrinesDokument19 SeitenTranspo Law Case DoctrinesKriszan ManiponNoch keine Bewertungen

- FAULT OR NEGLIGENCE CasesDokument17 SeitenFAULT OR NEGLIGENCE CasesTJ MerinNoch keine Bewertungen

- LRT vs. Navidad G.R. No. 145804. February 6, 2003Dokument12 SeitenLRT vs. Navidad G.R. No. 145804. February 6, 2003juleii08Noch keine Bewertungen

- GV Florida Vs BattungDokument3 SeitenGV Florida Vs BattungFRANCISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whitney v. RobertsonDokument4 SeitenWhitney v. RobertsonTessa TacataNoch keine Bewertungen

- BA Finance Corp V. CA (ATP)Dokument2 SeitenBA Finance Corp V. CA (ATP)k santosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Pitch Script Final DraftDokument4 SeitenProject Pitch Script Final Draftapi-294559944Noch keine Bewertungen

- Windscale Islands 2010Dokument152 SeitenWindscale Islands 2010Alexis QuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dayabhaga and Mitakshara PartitionDokument4 SeitenDayabhaga and Mitakshara PartitionAmiya Kumar Pati100% (1)

- PEOPLE v. MANUEL MACAL Y BOLASCODokument2 SeitenPEOPLE v. MANUEL MACAL Y BOLASCOCandelaria Quezon100% (1)

- An Tolo HiyaDokument109 SeitenAn Tolo HiyaJanjan DumaualNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument24 SeitenChapter 2Rolito Orosco100% (1)

- Chapter 11Dokument12 SeitenChapter 11James RiedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0ae743304afeb0fb49bb92a16a57e0b6Dokument2 Seiten0ae743304afeb0fb49bb92a16a57e0b6didinurieliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agreement Admitting A New Partner-DSADokument2 SeitenAgreement Admitting A New Partner-DSAdreamspacearchitectsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combo Ce TV Soundbar Jul Sept23Dokument5 SeitenCombo Ce TV Soundbar Jul Sept23Manishaa SeksariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infotech Foundation Et Al Vs COMELEC GR No 159139 Jan 13, 2004Dokument11 SeitenInfotech Foundation Et Al Vs COMELEC GR No 159139 Jan 13, 2004PrincessAngelicaMoradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transfer of PropertyDokument13 SeitenTransfer of PropertyRockstar KshitijNoch keine Bewertungen

- Declaratie de Intrare in Italia in EnglezaDokument2 SeitenDeclaratie de Intrare in Italia in EnglezaDan PopescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public International Law ProjectDokument27 SeitenPublic International Law ProjectPrateek virkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexual Offences and Juveniles.Dokument25 SeitenSexual Offences and Juveniles.Sujana KoiralaNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Lepanto Ceramics v. CADokument1 SeiteFirst Lepanto Ceramics v. CATaco BelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer Protection ActDokument43 SeitenConsumer Protection Actrahmat aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Certificate of Good Moral CharacterDokument11 SeitenCertificate of Good Moral CharacterAvelino Jr II PayotNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Muslim Concept of Surrender To God: by Mark NygardDokument6 SeitenThe Muslim Concept of Surrender To God: by Mark NygardmaghniavNoch keine Bewertungen

- in Re in The Matter of The Petition To Approve The Will of Ruperta Palagas Vs Palaganas GR No. 169144 January 26, 2011Dokument4 Seitenin Re in The Matter of The Petition To Approve The Will of Ruperta Palagas Vs Palaganas GR No. 169144 January 26, 2011Marianne Shen PetillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diploma in CCTV Management JP 118Dokument11 SeitenDiploma in CCTV Management JP 118Barrack OderaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest Trust and AgencyDokument131 SeitenDigest Trust and AgencyMohamad Job100% (2)

- Clat Mock Bank 026014282311bDokument36 SeitenClat Mock Bank 026014282311bBhuvan GamingNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Tecson V Comelec GR No 161434Dokument3 Seiten2 Tecson V Comelec GR No 161434rmpremsNoch keine Bewertungen

- York County Court Schedule For Dec. 14, 2015Dokument18 SeitenYork County Court Schedule For Dec. 14, 2015HafizRashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saludaga V FEUDokument20 SeitenSaludaga V FEUMicah Celine CarpioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics Commision Decision, Oct. 14, 2015Dokument4 SeitenEthics Commision Decision, Oct. 14, 2015Honolulu Star-AdvertiserNoch keine Bewertungen

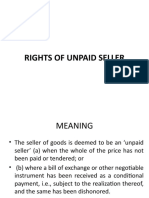

- Rights of Unpaid SellerDokument16 SeitenRights of Unpaid SellerUtkarsh SethiNoch keine Bewertungen