Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Registered Nurses Medication Management of The Elderly in Aged Care Facilities

Hochgeladen von

erg2301Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Registered Nurses Medication Management of The Elderly in Aged Care Facilities

Hochgeladen von

erg2301Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Original Article

Registered nurses’ medication management of

the elderly in aged care facilities inr_760 98..106

L.M. Lim1 RN, RSCN, BA (So Sc), BN (Com Health), MN, PhD (Ed),

L.H. Chiu2, RN, RM, ORTHONC (Hons), BAppSC (Nrsg Ed), MNS, Ed.D,

J. Dohrmann3 RN, BN, MN (Gerontic Nursing) &

K.-L. Tan4 RN, BN, MN (Ortho Nursing)

1 Senior Lecturer, International Director and Post-Graduate Course Coordinator, 2 Sessional Lecturer, School of Nursing and

Midwifery, Faculty of Health, Science and Engineering, Victoria University, 3 Manager Residential Care, Fronditha Anesi Aged

Care Services, Thornbury, 4 Associate Nurse Unit Manager, Epworth Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

LIM L.M., CHIU L.H., DOHRMANN J. & TAN K.-L. (2010) Registered nurses’ medication management of

the elderly in aged care facilities. International Nursing Review 57, 98–106

Background: Data on adverse drug reactions (ADRs) showed a rising trend in the elderly over 65 years using

multiple medications.

Aim: To identify registered nurses’ (RNs) knowledge of medication management and ADRs in the elderly

in aged care facilities; evaluate an education programme to increase pharmacology knowledge and prevent

ADRs in the elderly; and develop a learning programme with a view to extending provision, if successful.

Method: This exploratory study used a non-randomized pre- and post-test one group quasi-experimental

design without comparators. It comprised a 23-item knowledge-based test questionnaire, one-hour teaching

session and a self-directed learning package. The volunteer sample was RNs from residential aged care

facilities, involved in medication management. Participants sat a pre-test immediately before the education,

and post-test 4 weeks later (same questionnaire). Participants’ perceptions obtained.

Findings: Pre-test sample n = 58, post-test n = 40, attrition rate of 31%. Using Microsoft Excel 2000,

descriptive statistical data analysis of overall pre- and post-test incorrect responses showed: pre-test proportion

of incorrect responses = 0.40; post-test proportion of incorrect responses = 0.27; Z-test comparing pre- and

post-tests scores of incorrect responses = 6.55 and one-sided P-value = 2.8E-11 (P < 0.001).

Conclusion and implications: Pre-test showed knowledge deficits in medication management and ADRs in

the elderly; post-test showed statistically significant improvement in RNs’ knowledge. It highlighted a need for

continuing professional education. Further studies are required on a larger sample of RNs in other aged care

facilities, and on the clinical impact of education by investigating nursing practice and elderly residents’

outcomes.

Keywords: Adverse Drug Reactions, Aged Care, Continuing Education, Medication Management, Pharmacology,

RNs’ Knowledge

Introduction (ADR) is defined as any noxious and unintended response in a

Safe, effective medication management of the elderly in aged care patient or a research subject to a medication administered related

facilities remains a great challenge. An adverse drug reaction to any dose [International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH)

1996; Jordan 2007)]; while an adverse drug event is any noxious

Correspondence address: Dr Meng Lim, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Victoria and unintended response in a patient or a research subject to a

University, Melbourne City MC, Vic. 14428, Australia; Tel: 613-9919-2222;

medication administered, as well as other responses that are not

Fax: 613-9919-2832; E-mail: meng.lim@vu.edu.au.

necessarily caused by or related to that administered medication

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses 98

Nurses’ medication management of the elderly 99

(ICH 1996; Jordan 2007). According to Jordan (2008, p. 3), ‘some the ‘Measurement of the Quality Use of Medicines Component of

of the rarest and most serious adverse events are unpredictable, Australia’s National Medicines Policy’ revealed significant prob-

idiosyncratic and may occur at any situation’. lems with ADRs and adverse drug events (Department of Health

The ageing process can alter how a person metabolizes and and Ageing 2003). Therefore, new strategies are required to tackle

eliminates certain medications. For those suffering from dis- and minimize their occurrences.

eases, responses to drug therapy are difficult to predict, and

therefore, this can increase the risk of ADRs (Bressler & Bahl

2003). The elderly, being more prone to chronic and multiple Literature review

diseases, have higher uses of medicines; consequently, they have Whilst there are numerous studies on medication management

a higher risk of ADRs. Adverse drug reactions in the elderly are a and ADRs by medical practitioners and pharmacists (Pirmo-

common cause of hospital admissions, a common occurrence hamed et al. 2004; Routledge et al. 2003; Tulner et al. 2008), there

among people who are in hospital, and also a common cause of is limited research on the role of nurses in medication manage-

morbidity and death (Howard et al. 2006). Data on ADRs show a ment of the elderly in residential aged care facilities. In relation to

rising trend; particularly, in the elderly over 65 years using mul- the nursing studies, these were focused on exploring graduate

tiple medications (Roughead 2005). A Western Australian study nurses’ pharmacological knowledge, attitudes, experience and

found that the rate of ADRs associated with hospitalizations had perceptions of medication management and medication errors

more than doubled from 2.5 per 1000 person–years in 1981 to (Manias et al. 2004a), decision-making (Manias et al. 2004b) and

12.9 per 1000 person–years in 2002, especially in people aged 60 communication (Manias et al. 2005), and facilitating patient

years and above (Burgess et al. 2005, p. 267). adherence to medication regimes (Happell et al. 2002).

Australia’s National Strategy for Quality Use of Medicines, Several papers were published in the United Kingdom by

which was inaugurated in 1992, aims to improve knowledge of Jordan (2002, 2007) and Jordan et al. (2003, 2004) on ADRs. One

best practice and communicating information to health-care most relevant paper was on an observational study that explored

providers (Department of Health and Ageing 2003). The the effectiveness of a nurse-administered evaluation checklist,

Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council (APAC) and the in relation to nurse-prescribing initiatives and division of pro-

Pharmaceutical Health and Rational Use of Medicines commit- fessional responsibilities for medication management (Jordan

tee identified medication misadventure in residential aged care 2002). Although the study was specifically on patients who

facilities as a priority issue. They put forward recommendations received long-term antipsychotic medications, results showed

which led to the government funding the development of best that the evaluation checklist was able to guide nurse–client inter-

practice guidelines and research activities, and the Guidelines actions, increase nurses’ awareness of client’s health problems

for Medication Management in Residential Aged Care Facilities and provide guidance on actions available to address clients’

(APAC 2002). Within these guidelines, several recommendations issues. Interestingly, the study identified a ‘care-gap’ related to the

were made: (1) aged care facilities in Australia should set up monitoring and alleviating adverse effects of medication.

medication advisory committees to address issues concerning Similarly, a Canadian study reinforced the need for special

medication management, (2) the Commonwealth Government focus on the ordering and monitoring of medication to prevent

should fund the Residential Medication Management Review ADRs in long-term care settings (Gurwitz et al. 2005). The study

programme, which involves accredited pharmacists reviewing found 815 adverse drug events of which 42% were considered

resident’s medications and alerting the medical practitioner to preventable. The overall rate of adverse drug events was 9.8 per

potential risks of drug–drug interactions, inappropriate medica- 100 residents–months, with a rate of 4.1 preventable adverse

tion prescribing and risks for ADRs, and (3) nurses should detect drug events per 100 residents–months (p. 251).

ADRs, as they work with the elderly residents on a daily basis, Manias & Bullock (2002) explored Australian clinical nurses’

evaluate all medicine use for appropriateness, unwanted side perceptions and experience of graduate nurses’ pharmacology

effects, allergies, toxicity, medicine intolerance, medicine inter- knowledge, by collecting qualitative data using focus interviews.

actions and adverse reactions and respond appropriately, The results showed that: (a) graduate nurses had an overall lack

document and report this information. Nurses should also be of pharmacology knowledge, and (b) all other nurses also

required to have knowledge of pharmacokinetics, pharmacody- experienced difficulties in understanding and demonstrating

namics and pharmacogenetics in the elderly, along with main- pharmacological concepts in the clinical practice setting. This

taining contemporary knowledge and skills in relation to highlighted a significant need to improve pharmacology knowl-

pharmacology and health assessment (APAC 2002). Despite edge in order to improve practices to optimize the effective use of

these guidelines, the outcome report of the national indicators of medication in patients.

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

100 L. M. Lim et al.

Griffiths et al. (2004) examined the effectiveness of commu- and nursing were first regulated by statute in 1923 in Victoria,

nity nurses in improving knowledge and medication self- Australia. In 1993, the legislation was revised and all nurses are

management in a group of elderly receiving community nursing now termed registered nurses, classified according to their edu-

care. The research showed that nurses had the potential to play cational preparation by the Nurses Board of Victoria (NBV),

an effective role in the multidisciplinary team to improve the Australia (1993). The Health Professions Registration Act 2005

quality use of medicines in the elderly community clients. Fur- has governed all Victorian health registration boards (including

thermore, a Swedish study investigated whether a specific edu- the NVB) since July 2007:

cation programme could improve nurses’ knowledge of ADRs • Registered Nurse Division One (RN Div 1) are first level nurses

and ADRs reporting system (Bäckström et al. 2007). The pro- comprehensively trained with potential ability work in any

gramme led to significant improvement in nurses’ performance branch of nursing.

and knowledge. Although, the study was focussed pharmaceuti- • Registered Nurse Division Two (RN Div 2) are second level

cally to improve the ADRs reporting system, it illuminated a need nurses that work under the direction of a division one, equiva-

for education programmes to address issues relating to pharma- lent to an enrolled nurse in other Australian states.

cology knowledge. RN Div 2 (medication endorsed) are RN division 2 nurses who

As far back as 1994, Baker and Napthine stated that nurses’ have undertaken a course of study in medicines administration

responsibilities in drug management should include the ability to and have an endorsement of their registration granted by the

identify the risks and benefits of medicines. Indeed, registered NBV and can, and does administer medicines to patients that

nurses (RNs), as licensed and authorized health-care profession- have been prescribed by a doctor or nurse practitioner. The

als, have a key role and a professional responsibility in ensuring endorsement indicates the range of medicines that can be

the quality use of medicines. They are also responsible and administered. Some division 2 nurses can administer oral,

accountable for medicines, under the drugs and/or poisons leg- enteral and topical medicines, and some can also administer

islation of the state or territory in which they work. Furthermore, medicines by subcutaneous and intramuscular routes. The NBV

they must maintain contemporary knowledge and skill to utilize practicing certificate/card carried by each nurse has the specific

medicines appropriately (Australian Nursing Federation 2005). endorsement on it and can also be verified on the NBV register of

Therefore, it is the RNs’ role and responsibility in aged care nurses online.

facilities to manage medication, by adhering to safe practices.

These include accessibility to current information relating to

therapeutic substances used in the facility where they are Method

employed. RNs caring for the elderly should be aware of high- This exploratory study was a non-randomized pre- and post-test

risk medications and be able to identify susceptible residents in one group quasi-experiment without a comparator group, using

order to prevent, detect and report ADRs. Given the high risk of a factual-based test questionnaire and an education programme

ADRs in the elderly, as shown in the literature review, there is a (intervention) which comprised a one-hour teaching session and

need to explore the knowledge of RNs working in aged care a self-directed learning package (Appendix 1). The education

facilities. programme was based on effective medication management

and administration, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics,

Aim drug interactions, and ADRs in the elderly. The study was carried

The aims of the study were to: out in late 2007.

• examine RNs’ knowledge of medication management and

ADRs in elderly residents in aged care facilities,

• evaluate whether the introduction of an educational pro- Setting

gramme would increase RNs’ knowledge to recognize and Several residential aged care facilities in Victoria were asked if

prevent adverse drug reactions in elderly residents in aged care they would be interested in participating and seven responded

facilities, and with their approval and consent. In Australia, the residential aged

• develop a learning programme with a view to extending pro- care facilities are formerly known ‘nursing homes’. The defining

vision, if successful. characteristic of residential aged care is the combined provision

of care and accommodation to an older person by paid (and

Definition of RNs sometimes unpaid) workers in a setting other than the older

For the purpose of this study, the RNs in this study were RN person’s own home (Department of Human Services, Victoria

Division 1 and RN Division 2 (medication endorsed). Nurses 2000).

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

Nurses’ medication management of the elderly 101

Sample vided for participants to complete the questionnaire. Immedi-

The participants were a volunteer sample from a target of RNs ately after the pre-test, the education programme was taught to

(Div1 and Div2) currently working in residential aged care facili- participants in a classroom presentation lasting an hour. The

ties and who were involved with the administration and man- education programme was conducted in an environment con-

agement of medication. The sample in the pre-test was n = 58, ducive for learning, and participants were encouraged to actively

but in the post-test was n = 40 with an attrition rate of 18 (31%). participate. The teaching session included several examples of

real case studies, which stimulated interest and sound discus-

Sampling process sions. At completion of the lecture, participants were each

The University Human Ethics Committee granted Ethics provided with a self-directed learning package based on the edu-

approval. The aged care facilities were given a brochure to invite cation session they had attended to enhance learning. Partici-

the RNs who were involved with administration and manage- pants were encouraged to use the self-directed learning package

ment of medication to meet with the researchers in each of the to revise and consolidate their learning in their own time. Par-

facilities to explain their involvement, the study purpose and ticipants were also informed of the date to return 4 weeks later to

aim. Each RN was given an information sheet and was informed undertake the post-test. The reason for the four-week period was

that they would remain anonymous with no identifiable code on to allow participants adequate time to assimilate the information

each questionnaire. Matched pairs were not obtainable because with the aid of the learning package.

participants had to be reassured that their job would not be

jeopardized and that this study was only examining improve- Phase two

ments in group knowledge and not individual knowledge after Post-test took place 4 weeks later when participants returned to

the intervention of an educational programme. Confidentiality undertake the post-test to re-assess their level of knowledge and

was maintained at all times. Participation was voluntary and assessment skills with the same set of questionnaire. The slight

written informed consent was obtained from individual RNs difference in the post-test questionnaire was the inclusion of five

who agreed to participate in the study. open-ended questions requiring participants to self-report on

their perceptions of the effectiveness of the in-service education

Measurement and self-directed learning package.

The pre- and post-test questionnaire comprised two sections.

The first was a 6-item questionnaire related to demographic data Reliability and validity

on sex, age, level of RN division, qualification, years of nursing A couple of aged care nurses and a pharmacist were invited to

experience and post graduate or nursing specialization. The review the questionnaire for face validity and modifications were

second section was a self-administered questionnaire consisting made where suggested. All these factual-based knowledge ques-

of 23 items of factual-based questions: 17 multiple choice knowl- tions were carefully selected by references to the literature (see

edge questions and 6 true/false statements requiring participants Table 2). As different aged care facilities were very far apart from

to choose the correct answer. The questions measured the acqui- one another, and also for the convenience of the working RNs, it

sition of recent knowledge and level of assessment skills in was necessary to run the educational programmes at these dif-

medication administration in aged care facilities; nurses’ role ferent aged care facilities’ venues to attract as many participants

in aged care facilities; pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics as possible. Therefore, the same data collection process was

in the elderly; drug interactions; adverse drug reactions; and the repeated seven times at the seven different facilities. To ensure

reasons why the elderly are at greater risk of experiencing ADRs. consistency of teaching and to avoid compromising the study

A summarized version of the questions is presented in Table 2. rigor, an experienced nurse clinician delivered all the teaching

Additionally, the post-test questionnaire had 5 open-ended sessions.

questions for participants to express their perceptions of the

effectiveness of the education session and self-directed learning Data analysis

package. Statistical analysis of incorrect responses were calculated for pre-

and post-tests results using Microsoft Excel 2000. The statistician

Data collection method recommended this statistical package because the study was

about population proportions, as we were unable to obtain

Phase one pairing information (Schork & Remington 2000; Weiss 2005).

The participating RNs completed the test questionnaire prior to Because there is no matching-pairs information on the partici-

attending the educational programme. Adequate time was pro- pants in the pre- and post-test data, we could not construct a

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

102 L. M. Lim et al.

Table 1 Comparing overall pharmacology knowledge level before and after education programme: Z-test and P-value based on the 23-item test questionaire

Pre-test n = 58 Post-test n = 40 Z-Test P-value

Total number of correct responses 799 674

Total number of incorrect responses 535 246

Total number of responses 1334 920

Proportion of incorrect responses 0.40 0.27 Z = 6.55 2.8E.11*

*P < 0.001.

contingency table, and the Z-test procedure for two proportions they returned for the post-test. All the participants thought the

was appropriate (Schork & Remington 2000; Weiss 2005). This teaching session was beneficial. They said that it gave them more

test does not require information on means and standard devia- information about drugs that should not be used, their usage and

tions. Descriptive statistics were used to present demographic their side effects in the elderly residents. For example, one par-

characteristics of the study sample and data of incorrect ticipant wrote: ‘It has increased my understanding of medication

responses to the 23-item factual-based test questions. and awareness of the dangers of prescription and drug–drug inter-

actions in the elderly.’

Interpretation of results All participants except one expressed that the self-directed

Altogether, 58 RNs participated in the pre-test vs. 40 in the post- learning package was useful and easy to understand, and had

test, showing an attrition rate of 18. RN’s demographic charac- expanded their knowledge about ADRs in the elderly. All felt that

teristics data from both pre and post are summarized in Table S1. their attitude had changed toward medications of the elderly.

There were 49 vs. 34 RNs (Div 1) and 9 vs. 6 RNs (Div2- They became more careful and vigilant when giving medications

medication endorsed); 51 vs. 33 females and 7 males. The ages and observing for any adverse reactions experienced by the

ranged from 20–60 years. The years of working experience elderly residents. When asked about their thoughts while admin-

ranged from 1–50 years. istering medication to the elderly, most wrote that they became

The RNs (Div2) held the Associate Diploma Certificate IV, more aware of the need to monitor reactions and report them, if

while the RNs (Div1) were either hospital-trained or held tertiary necessary. For example, one participant wrote: ‘My professional

qualifications; 2 masters in gerontic nursing; 1 master in neuro- responsibility and the needs of the resident and also observing for

science nursing; 6 vs. 5 graduate diploma in gerontic nursing; the positive and negative effects of the medication administered.’

15 vs. 8 other post graduate certificate qualification in different Another stated: ‘I would be less inclined to take for granted doctors

specialities; and 27 vs. 20 had no extra post-qualification studies. prescribing Xs medication and instead would question more.’

Statistically, the overall result showed a high significant differ- Generally, most wrote that they had a clearer picture regarding

ence in the RNs’ knowledge: proportion of incorrect responses ADRs and the risks of drug–drug interactions associated with

of the pre-test = 0.40, proportion of incorrect responses of the polypharmacy in the elderly.

post-test = 0.27, Z-test = 6.55, and one-sided P-value = 2.8E-11

(P < 0.001) (Table 1).

The results of incorrect responses from the pre- and post-test Limitations of the study

questionnaire for each of the 23-item factual-based knowledge Several limitations should be considered when interpreting

questions are presented in Table 2. The post-test responses the findings of this study. The attrition rate was a problem.

showed improvements in all aspects of the knowledge questions, Unfortunately, not all participants returned to undertake the

some more significant than others. The individual questions post-test 4 weeks later. Absence of a control group is a limita-

which showed high statistical significant differences in the reduc- tion (Grimes & Schulz 2002; Jordan 2000). This was an explor-

tion of incorrect responses between the pre- and post-test scores atory study. Another limitation was not being able to obtain

are marked with asterisks in Table 2. identifiable code or matched pairs’ data for further statistical

analysis to investigate the value of the education programme.

Participants’ perceptions of education programme Furthermore, the RNs who returned for the post-test could be

The participants were requested to describe their perceptions of nurses who were more committed to learning and might skew

the teaching session and self-directed learning package when the result.

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

Nurses’ medication management of the elderly 103

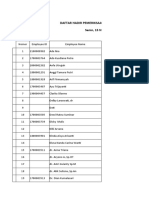

Table 2 Question wise – comparing pharmacology knowledge level before and after education programme: number of incorrect responses in percentages,

Z-test and P-values

N Questions/subjects Pre-test Post-test Z-Value P-value

n = 58 n = 40

N % N %

1 Duty of care for nurses in aged care facilities (APAC 2002). 1 1.7 2 5.0 -0.93 0.82

2 80% of ADRs that occur in the elderly are type A in nature. (Routledge et al. 2003). 38 65.5 11 27.5 3.70 <0.001*

3 The ageing process involves increase body fat, decreased muscle mass and decreased body water (Bressler & 39 67.2 11 27.5 3.87 <0.001*

Bahl 2003).

4 Renal flow in the elderly decreases by 1% per year after the age of 50. (Bressler & Bahl 2003). 11 19.0 6 15.0 0.51 0.31

5 The absorption phase of pharmacokinectics is generally not a problem in the elderly (Mangoni & Jackson 42 72.4 18 45.0 2.74 <0.01*

2004).

6 Pharmacodynamics can be defined as the time course and effect of drugs on cellular and organ function 16 27.6 9 22.5 0.57 0.29

(Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy 2005).

7 Due to altered pharmacokinetics and pharmocodynamics, the elderly often need less medication (Bressler 12 20.7 4 10.0 1.41 0.08

& Bahl 2003).

8 In the elderly, the dosage of drugs that are renally excreted, such as digoxin, need to be reduced (Mangoni 21 36.2 6 15.0 2.31 0.01*

& Jackson 2004).

9 When an elder is prescribed greater than eight medications research suggested that the likelihood of an 51 87.9 21 52.5 3.90 <0.001*

adverse drug reaction occurring approaches 100% (Rollason & Vogt 2003).

10 When an elder takes two concurrent medications for more than 60 days, it is a possible indicator of 30 51.7 23 57.5 -0.56 0.71

polypharmacy (Rollason & Vogt 2003).

11 Nausea and vomiting are the common complaints for digoxin toxcity in an elder (Williams & Kim 2003). 43 74.1 29 72.5 0.18 0.43

12 Having a previous ADR to a particular medication means that a person is at increased risk of developing 51 87.9 17 42.5 4.80 <0.001*

an ADR with the commencement of another unrelated drug. (True) (Atkin et al. 1999).

13 Importance of knowledge when administering warfarin (Williams & Kim 2003). 12 20.7 4 10.0 1.41 0.08

14 With administration of oral hypoglycaemics the main cause for ADR is as result of the resident not eating 13 22.4 12 30.0 -0.85 0.80

meals (Stahl & Berger 1999).

15 Residents with Lewy body dementia are known to have severe antipsychotic sensitivity reactions (Finkel 25 43.1 8 20.0 2.38 <0.01*

2004).

16 Valium is a benzodiazepine and is a highly lipid soluble drug, and considered inappropriate for use in the 37 63.8 14 35.0 2.80 0.002*

elderly as its half life may be increased up to 300 hours (Tanaka 1999).

17 Medications that have an anticholinergic effect, such as haloperidol, can cause ADR in the elderly such as 30 51.7 19 47.5 0.41 0.34

increased confusion, urinary retention, dry mouth and blurred vision (Bhana & Spencer 2000).

18 Being elderly and male can increase the risk of adverse drug reactions. (True) (Wiffen et al. 2002). 17 29.3 13 32.5 -0.34 0.63

19 Olanzapine (zyprexia) is recommended for use in elderly people with a history of obesity or diabetes. 9 15.5 6 15.0 0.07 0.47

(False) (Finkel 2004).

20 Conventional antipsychotics are no longer recommended for use in the elderly. (True) (Bhana & Spencer 20 34.5 8 20.0 1.56 0.06

2000).

21 ADRs are continuing problem for the elderly and registered nurses are in the position to increase vigilance 4 6.9 0 0.0 1.70 0.04*

to help improve health outcomes in this vulnerable population. (True) (Gurwitz et al. 2005).

22 A pharmacodynamic interaction occurs when the pharmacological effects of one drug alters the response 6 10.3 3 7.5 0.48 0.32

to another drug even though the two types are not themselves directly related. (True) (Bressler & Bahl

2003).

23 A pharmacokinetic drug interaction can alter the concentration of drug in the systemic circulation through 7 12.1 2 5.0 1.19 0.12

interactions occurring at any stage: that is during absorption, distribution, metabolism or excretion

(True) (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy 2005).

*Significant difference.

ADR, adverse drug reactions.

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

104 L. M. Lim et al.

Discussion reaction can alter the concentration of drugs in the systemic

Effective, successful medication management of the elderly circulation, due to drug interactions, which can occur at any

requires safe administration, vigilant assessment, monitoring of stage during absorption, distribution, metabolism or excretion

residents and sound knowledge of pharmacokinetics, pharmaco- (Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy 2005). All these are the

dynamics, ADRs and risks of drug interactions associated with fundamentals of pharmacology taught to RNs, but the result of

polypharmacy. RNs have a professional role responsibility to be the study showed that not all participants were aware of these

vigilant for ADRs, particularly in people who are vulnerable such fundamentals.

as the elderly who often are unable to eliminate drugs efficiently Patients taking antipsychotic agents, anticoagulants, diuretics

(Jordan 2008). Burgess et al. (2005) maintained that although it and antiepileptic are at increased risk to ADRs (Jordan 2008).

was important to identify ADRs, it was equally important to Over 50% of participants did not know that medications that

detect it early and prevent it. The increasing ageing population have an anticholinergic effect, e.g. Haloperidol, can cause ADR in

highlights the importance of nurses’ responsibility in aged care the elderly such as, increased confusion, urinary retention, dry

facilities to care for the elderly who require special attention. The mouth and blurred vision (Bhana & Spencer 2000). In spite of

majority of previous nursing studies have used experiential the education, 47.5% gave incorrect responses. Non-steroidal

qualitative design or opinion-based questionnaire seeking agree- anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and oral anticoagulants have

ment responses rather than specific responses to factual-based a high innate toxicity; both groups require close monitoring for

questions on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. There- their safe use and are often used for elderly residents who are

fore, in this study, these 23 items of factual-based knowledge more susceptible to ADRs (Howard et al. 2006). Warfarin is a

questions were specifically developed to elicit information that commonly prescribed anticoagulant, yet some participants were

could ascertain RNs’ level of knowledge and the accuracy of their unaware that the use of NSAIDs with Warfarin is associated with

knowledge in relation to medication management and drug reac- an increased risk of severe ADRs.

tions experienced by elderly residents in aged care facilities. When the elderly are prescribed greater than eight medica-

The proportion of incorrect responses of the pre-test was high; tions, research studies suggest that the likelihood of ADRs occur-

it revealed a lack of knowledge by RNs in regards to safe medi- ring approaches 100% (Rollason & Vogt 2003). It raises concerns

cation management and administration in the aged care facili- that not all of the study participants were cognizant of this fact,

ties. The proportion of incorrect responses of the post-test (after despite the education session and learning package. Valium is a

the introduction of the education session and self-directed benzodiazepine and is a highly lipid soluble drug. It is considered

learning package) was significantly lower than the pre-test. This inappropriate for use in the elderly as its half-life may be

demonstrated that RNs’ knowledge of medication management increased up to 300 h (Tanaka 1999), but 63.8% in the pre-test

had improved substantially. Statistically, the difference was group did not give the correct answer. The knowledge improved

highly significant with Z = 6.55 and one-sided P < 0.001* with a significant drop of incorrect responses to 35%, but not

(Table 1). Overall, there was an improvement of knowledge in all enough for providing quality care to elderly residents. RNs need

the questions with some showing more improvement than to be aware that having a previous ADR to a particular medica-

others. Significant difference was indicated in various important tion means that a person is at an increased risk of developing

aspects of the questionnaire as shown by asterisks in Table 2. an ADR with the commencement of another unrelated drug

This study has, however, raised an issue of concern in regard to (Atkin et al. 1999). Although there is significant improvement

the need for the continuing professional education in this area. in knowledge after the education programme, there is still a

Prior to the education programme, 87.9% of RNs were unaware need for further continuing education.

that the elderly, who had a previous ADR to a particular medi- This study has demonstrated that the education session and

cation, would be more likely to develop an ADR with the com- learning package did improve RNs’ level of knowledge in

mencement of another unrelated drug. Nausea and vomiting medication and medication management, even though there were

are two most common complaints in suspected digoxin toxicity. several aspects where improvement were only marginal. A parallel

As a result of the ageing process, the elderly are at a high risk can be drawn between Jordan’s (2002) study, which revealed a

of developing toxicity (Williams & Kim 2003), yet the result need for further development by nurses in the management of

revealed that 74% of RNs were unable to recognize symptoms of ADRs for those suffering long term psychotic issues, and this

side effects. A pharmocodynamic interaction can occur when study, which reaches the same conclusion in terms of elderly care,

pharmacological effects of one drug alter the response to another as both studies involved classes of individuals who require special

drug, even though the two types are not themselves directly attention. A previous study by Manias et al. (2004a) found that

related (Bressler & Bahl 2003). Also, any pharmacokinetic drug although graduate nurses attempted to demonstrate safe medica-

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

Nurses’ medication management of the elderly 105

tion practices, especially during medication administration, they Chiu was involved in the study conception, design, acquisition of

did not regularly monitor medication effects following adminis- data, analysis/interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript

tration. In contrast, in this study, participants wrote that they and review of the content. Jayne Dohrmann was involved in the

would be more vigilant in monitoring medication effects during study conception, design, material support and review of the

and following medication administration. Nevertheless, with the content. Kim Lai Tan was involved in the study design, acquisi-

current world emphasis on evidence-based practice, the effective- tion of data, provision of statistical technical support and review

ness of education programmes cannot be based solely on testing of the content.

participants’ knowledge and satisfaction, but also need to be

linked to improved clinical outcomes (Jordan 2000).

References

Atkin, P., Veitch, E. & Ogle, J. (1999) The epidemiology of serious adverse

Conclusion drug reactions among the elderly. Drugs and Aging, 14 (2), 141–152.

This pilot study set out to evaluate an education programme Australian Nursing Federation (2005) Quality use of medicines, ANF

aimed to increase awareness of and knowledge in pharmacology Position Statement, ANF, Australia. (accessed 15 February 2009).

to improve nursing practice in aged care facilities. It is arguable img.2181759.0001.pdf.

that this education programme has benefited the participants. Australian Pharmaceutical Advisory Council (Nov. 2002) Guidelines for

Inadvertently, this study has highlighted an area of concern relat- medication management in residential aged care facilities (3rd Edn). Com-

ing to the lack of knowledge in medication management among monwealth Department of Health and Ageing, Publication Production,

RNs caring for the elderly residents in aged care facilities. Canberra, Australia. Available at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/

main/publishing.nsf/Content/nmp-pdf-resguide-cnt.htm (accessed 27

However, the findings cannot be generalized to a wider popula-

July 2007).

tion of RNs working in aged care facilities. Further studies are

Bäckström, M., Ekman, E. & Mjörndal, T. (2007) Adverse drug reaction

required on a larger sample of RNs in other aged care facilities

reporting by nurses in Sweden. European Journal of Clinical Pharmocol-

within the region, as well as on the clinical impact of an educa- ogy, 63 (6), 613–618. (accessed 6 February 2009). DOI: 10.1007/s00228-

tion programme by evaluating nursing practice and elderly resi- 007-0274-8

dents’ outcomes in aged care facilities. Baker, H. & Napthine, R. (1994) Nurses and Medication: A Literature

The nursing implication is that the study has identified a need Review. Australian Nursing Federation, Melbourne, Victoria.

for intervention to improve RNs pharmacological knowledge, Bhana, N. & Spencer, C. (2000) Risperidone: a review of its use in the

medication administration and management in aged care facili- management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of demen-

ties. Despite the limitations of this study, the result gives some tia. Drugs and Aging, 16 (6), 451–471.

weight to the importance of providing an appropriate continu- Bressler, R. & Bahl, J. (2003) Principles of drug therapy for the elderly

patient. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 78 (12), 1564–1577.

ing professional education programme. It seems that an inter-

Burgess, C., D’Arcy, C., Holman, C. & Satti, A. (2005) Adverse drug reac-

vention such as continuing education is mandatory in order to

tions in older Australians, 1981–2002. Medical Journal of Australia,

improve nursing practice that will minimize the risk of ADRs.

182 (6), 267–270. Available at: http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/

182_06_210305/bur10464_fm.html (accessed 6 February 2008).

Acknowledgements Department of Human Services, Victoria (2000) High Care

This study received a grant with thanks from the Health Career Residential Aged Care Facilities in Victoria. Available at: http://

International Pty. Ltd. Melbourne, Australia. Our thanks and www.health.vic.gov.au/agedcare/downloads/residential.pdf (accessed 28

appreciations are extended to: (a) all participating aged care May 2009).

facilities and RNs for their commitment which made this study Department of Health and Ageing (2003) Quality Use of Medicines and

possible, (b) Dr Fuchan Huang, Senior Lecturer, School of Com- Pharmacy Research Centre. Measurement of the Quality Use of Medicines

puter Science and Mathematics, Victoria University, Australia, Component of Australia’s National Medicines Policy. Department of

for his expert statistical advice, (c) Ritamigawati Jamali, Clinical Health and Ageing, Canberra, Australia. Available at: http://health.gov.au/

internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/Content/nmp-pdf-qumnmp-cnt.htm

Nurse Specialist, for her support, and (d) the Anonymous

(accessed 23 August 2007).

Reviewer who went through much effort with our manuscript

Finkel, S. (2004) Pharmacology of antipsychotics in the elderly: a focus on

and gave very constructive comments.

atypicals. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 52 (12), S258–S265.

Griffiths, R., Johnson, M., Piper, M. & Langdon, R. (2004) A nursing inter-

Author contributions vention for the quality use of medicines by elderly community clients.

Lee Meng Lim was involved in the study conception, design, International Journal of Nursing Practice, 10 (4), 166–176.

analysis/interpretation of data and critical revisions for impor- Grimes, D. & Schulz, K. (2002) An overview of clinical research. Lancet,

tant intellectual content, and review of the content. Lee Huang 359, 57–61.

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

106 L. M. Lim et al.

Gurwitz, J.H., et al. (2005) The incidence of adverse drug events in two Pirmohamed, M., et al. (2004) Adverse drug reactions as cause of admis-

large academic long-term care facilities. The American Journal of sion to hospital: prospective analysis of 18, 820 patients. BMJ, 329,

Medicine, 118, 251–258. (accessed 6 February 2008). Doi:10.1016/ 15–19.

j.amjmed.2004.09.018 Rollason, V. & Vogt, N. (2003) Reduction of polypharmacy in the elderly:

Happell, B., Manias, E. & Pinikahana, J. (2002) The role of the inpatient a systematic review of the role of the pharmacists. Drugs and Aging,

mental health nurse in facilitating patient adherence to medication. 20 (11), 817–832.

International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 11, 251–259. Roughead, E. (2005) Managing adverse drug reactions: time to get serious.

Howard, R.L., et al. (2006) Which drugs cause preventable admissions to Medical Journal of Australia, 182 (6), 264–265. Available at: http://

hospital? A systematic review. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, www.mja.com.au/public/issues/182_06_210305/rou10926_fm.html

63 (2), 136–147. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.xx (accessed 13 June 2008).

International Conference of Harmonisation (1996) Guidance for Industry Routledge, P., O’Mahony, M. & Woodhouse, K. (2003) Adverse drug reac-

E6 Good Clinical Practice: Consolidated Guidance. US Department of tions in elderly patients. British journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 57 (2),

Health and Human Services. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/ 121–126.

guidance/index.htm (accessed 27 May 2009). Schork, M.A. & Remington, R.D. (2000) Test on differences between the

Jordan, S. (2000) Educational input and patient outcomes: exploring the parameters of two binomial distribution (Sect 7–6, p. 101). In Statistics

gap. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31 (2), 461–471. with Applications to the Biological & Health Sciences, 3rd edn. Prentice

Jordan, S. (2002) Managing adverse drug reaction: an orphan task. Journal Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

of Advanced Nursing, 38 (5), 437–448. Stahl, M. & Berger, W. (1999) Higher incidence of severe hypoglycaemia

Jordan, S. (2007) Adverse drug reactions: reducing the burden of treat- leading to hospital admission in Type 2 diabetic patients treated with

ment. Nursing Standard, 21 (34), 35–41. long-acting versus short-acting sulphonylureas. Diabetic Medicine,

Jordan, S. (2008) The Prescription Drug Guide for Nurses. Open University 16 (7), 586–590.

Press, McGraw Hill, London, England. Tanaka, E. (1999) Clinically significant pharmacokinetic drug interactions

Jordan, S., Griffiths, H. & Griffith, R. (2003) Continuing professional with benzodiazepines. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics,

development: administration of medicines. Part 2 Pharmocology. 24 (5), 347–355.

Nursing Standard, 15 (23), 45–52. Tulner, L., et al. (2008) Drug-drug interactions in a geriatric outpatient

Jordan, S., Knight, J. & Pointon, D. (2004) Monitoring adverse drug reac- cohort-prevalence and relevance. 25 (4), 343–355. 1170-229X/08/

tions: scales, profiles and checklists. International Nursing Review, 51, 004.0343.$48.00/0.

208–221. Weiss, N.A. (2005) Introductory Statistics, 7th edn. Pearson/Addison

Mangoni, A. & Jackson, S. (2004) Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics Wesley, New York.

and pharmacodynamic: basic principles and practical applications. Wiffen, P., Gill, M., Edwards, J. & Moore, A. (2002) Adverse drug reactions

British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 57 (1), 6–14. in hospital patients. Bandolier Extra 2002, 1–15. Available at: http://

Manias, E. & Bullock, S. (2002) The educational preparation of under- www.jr.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/extraforbando/ADRPM.pdf (accessed 11

graduate nursing students in pharmacology: clinical nurses’ perceptions September 2005).

and experiences of graduate nurses medication knowledge. International Williams, B. & Kim, J. (2003) Cardiovascular drug therapy in the elderly:

Journal of Nursing Studies, 39, 773–784. theoretical and practical considerations. Drugs and Aging, 20 (6),

Manias, E., Aitken, R. & Dunning, T. (2004a) Medication management by 445–463.

graduate nurses: before, during and following medication administra-

tion. Nursing and Health Science, 6, 83–91.

Manias, E., Aitken, R. & Dunning, T. (2004b) Decision-making models Supporting information

used by ‘graduate nurses; managing patients’ medication. Journal of

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online

Advanced Nursing, 47 (3), 270–278.

version of this article:

Manias, E., Aitken, R. & Dunning, T. (2005) Graduate nurses’ communica-

Table S1 Demographics of participants.

tion with health professionals when managing patients’ medication.

Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 354–362.

Appendix 1 Key elements of the education programme

Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (2005) Considerations for effective Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the

pharmacotherapy. Drug therapy in the elderly, Section 22, Chapter 304. content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by

Available at: http://www.merck.com/mrkshared/mmanual/section22/ the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be

chapter304/304e.jsp (accessed 3 September 2005). directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Nurses Board of Victoria (NBV), Australia (1993) Nurses act. Health Pro-

fessional Registration Act 2005. Available at: http://www.nbv.org.au

(accessed 13 June 2008).

© 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 International Council of Nurses

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- SPDokument15 SeitenSPchandru sahanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Jadwal Skrining, 15-20 Nov 2021Dokument45 SeitenJadwal Skrining, 15-20 Nov 2021EvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Polypharmacy in The ElderlyDokument3 SeitenPolypharmacy in The ElderlyJC Cris DuroyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Medication Administration WorksheetDokument42 SeitenMedication Administration WorksheetPandesal with EggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- CV April2022Dokument5 SeitenCV April2022api-457976135Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- A. Pharmacodynamic: Mcu-Fdtmf Colloge of Medicine Department of Pharmacology Board QuestionsDokument14 SeitenA. Pharmacodynamic: Mcu-Fdtmf Colloge of Medicine Department of Pharmacology Board QuestionsJo Anne100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Revised WTP Leaflet FinalDokument3 SeitenRevised WTP Leaflet FinalShrutangi VaidyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Guidelines For The Adminstration of Drugs Via Enteral Feeding TubesDokument13 SeitenGuidelines For The Adminstration of Drugs Via Enteral Feeding TubesNegreanu AncaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- 15' (Company) Korea Innovative Pharmaceutical CompanyDokument64 Seiten15' (Company) Korea Innovative Pharmaceutical CompanyNguyễn Uyên Đạt ThịnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Stenorol® Crypto - OS - Brochure - EN - v01 - 1020Dokument2 SeitenStenorol® Crypto - OS - Brochure - EN - v01 - 1020DrivailaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- DB CdcethicsgDokument84 SeitenDB CdcethicsgMichael WeissNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Sustained and Controlled Release Drug Delivery SystemsDokument28 SeitenSustained and Controlled Release Drug Delivery SystemsManisha Rajmane100% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Handbook1 Non Steroidal 1Dokument60 SeitenHandbook1 Non Steroidal 1مها عقديNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Syllabus MPHDokument69 SeitenSyllabus MPHGajanan Vinayak NaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- E-Catalog 2021Dokument33 SeitenE-Catalog 2021fiannysjahjadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prescribing Authority TableDokument7 SeitenPrescribing Authority TablearifadamjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Febuxostat - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument3 SeitenFebuxostat - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediagode ghytrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Propar & Propar Forte - Jack PharmaDokument4 SeitenPropar & Propar Forte - Jack PharmaFaiza anwerNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Sayeed TeachingDokument8 SeitenCV Sayeed TeachingGopal ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medicines Administration 1 Understanding Routes of AdministrationDokument3 SeitenMedicines Administration 1 Understanding Routes of AdministrationJosa Camille BungayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cana JanDokument257 SeitenCana JanCAlexandraAlexaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transdermal Delivery of DrugsDokument17 SeitenTransdermal Delivery of DrugsRitha PratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faculty of Engineering and Science Examination Timetable May 2017Dokument22 SeitenFaculty of Engineering and Science Examination Timetable May 2017Obioha Nbj NnaemekaNoch keine Bewertungen

- pEBC MCQ Sample QuestionsDokument8 SeitenpEBC MCQ Sample QuestionsNoah Mrj70% (10)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Summary and ConclusionsDokument5 SeitenSummary and ConclusionsHrishikeshNoch keine Bewertungen

- USONA INSTITUTE - 2018 - Psilocybin Investigator BrochureDokument59 SeitenUSONA INSTITUTE - 2018 - Psilocybin Investigator BrochureSandro RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harga Obat Victory Dexa 2022Dokument9 SeitenHarga Obat Victory Dexa 2022zulfisaputra89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Faculty of Pharmacy Student CouncilDokument14 SeitenFaculty of Pharmacy Student CouncilFish BallNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cefuroxime Drug Study ChanDokument5 SeitenCefuroxime Drug Study Chanczeremar chanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Daftar Obat-ObatanDokument5 SeitenDaftar Obat-Obatanklinik warna ayu jaya medikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)