Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Course Manual: Week Broad Topic Particulars Essential Readings - Section Nos and Cases (If Any) Secondary Literature

Hochgeladen von

Yasharth ShuklaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Course Manual: Week Broad Topic Particulars Essential Readings - Section Nos and Cases (If Any) Secondary Literature

Hochgeladen von

Yasharth ShuklaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Course Manual

28 February 2018 08:52

Portions: Hypos.

Make case notes. Concentrate on facts. Clear concepts

Can take Registration Act

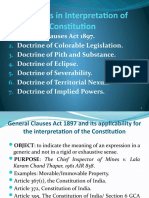

Week Broad Topic Particulars Essential readings - Section Nos and Secondary Literature

cases (if any)

1 Introduction Meaning of property, theories of Meaning of property, theories of Alison Clarke and Paul Kohler,

property. property. Property Law: Commentary and

Property, capital, and the Property, capital, and the modern Materials (Cambridge: Cambridge

modern economy. economy. University Press, 2005), 19–26.

General Overview of relevant Hohfeld’s Fundamental Legal

land and property legislations. Conceptions. WH Hohfeld, Some Fundamental Legal

Overview of relevant land and Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning,

property legislations, including in 23(1) Yale LJ 16 (1913).

relation to rent control, land

reforms, land ceiling. WH Hohfeld, Fundamental Legal Conceptions as

Applied in Judicial Reasoning, 26(8) Yale LJ 710

(1917).

2-3 Constitutional Law Eminent Domain, Right to Articles 19(1)(f) and Article 31 of Namita Wahi, Property, Oxford Handbook of the

and Property Property as a Fundamental the Constitution before the 44th Indian Constitution (Oxford: Oxford University

Right; Amendment Act 1978. Press, 2016), p. 943-966.

44th Amendment Act. 300A of the Constitution of India

1. Bela Banerjee v. State of West Austin, Granville. Working a

Bengal- AIR 1954 SC 170 Democratic Constitution: The Indian Experience.

2. Vajravelu Mudaliar v. Special New Delhi; New York: Oxford University Press,

Deputy Collector- AIR 1965 SC 1999. Pp. 69-122, 196-277, 420-430.

1017

3. Union of India v. Metal R Rajesh Babu, Constitutional Right to Property

Corporation of India Ltd- AIR 1967 in Changing Times: The Indian Experience

SC 634 (September 13, 2012). Vienna Journal on

4. State of Gujarat v. Shantilal International Constitutional Law, Vol. 6, No. 2,

1969(1) SCC 509 pp. 213-247, 2012.

5. R.C. Cooper v. Union of India, 1970

(2) SCC 298 (Bank Nationalization

case)

6. KT Plantation v. State of

Karnataka, (2011) 9 SCC 1

3-4 Types of Property Definition of Movable and S. 3 TPA, S. 3(26) General Clauses Specific Relief Act – S. 5 and S. 6

Immovable property. Act and the Registration Act.

7. Ananda Behera v. State of Orissa Commissioner Of Central Excise,Ahmedabad v

(1955) 2 SCR 919 Solid And Correct Engineering Works And

8. Shantabai v State of Bombay, AIR Others, (2010) 5 SCC 122

1958 SC 532

9. Suresh Chand v. Kundan (2001)

10 SCC 221

10. Duncan Industries Ltd. v State of

Uttar Pradesh, (2000) SCC 633

11. Triveni Engineering & Industries

Limited v. Comm. of Central

Excise (2000) 7 SCC 29

12. Suresh Chand v. Kundan (2001)

10 SCC 221

13. State of Orissa v. Titaghur Paper

Mills Company Limited, AIR 1985

SC 1293

14. Ananda Behra v. State of Orissa

(1955) 2 SCR 919

5 Registration and Requirement of Registration/ S. 17 and 18 of the Indian Indian Stamp Act to be referred to and the

Stamp Duty Stamping; and consequences of Registration Act schedule to be discussed briefly

Failure to Register/ Stamp. Indian Stamp Act

15. Suraj Lamps Pvt. Ltd. v State of

Haryana, 2011 (11) SC 438.

5 Transfer What is Transfer? What cannot Ss. 2(d), 5, 6, 43, 8 and 9, TPA.

Property Law Page 1

5 Transfer What is Transfer? What cannot Ss. 2(d), 5, 6, 43, 8 and 9, TPA.

be Transferred? Operation of 16. V. N. Sarin v. Ajit Kr. Poplai AIR

transfer? 1966 SC 432

17. Kenneth Solomon v. Dan Singh

Bawa, AIR 1986 Del 1

6 General Rules of Conditional Transfers, Restraints Ss. 10, 11 and 40, 12; 25-34, TPA.

Transfer on Alienation and Enjoyment. 18. Muhammad Raza v. Abbas Bandi Delhi Dayalbagh Co-Operation House Building

Bibi, (1932) I.A. 236 Society Limited v Registrar Cooperative Societies

19. Zoroastrian Co-operative Housing and others, 2012 (195) DLT 459

Society Ltd. V. District Registrar,

Co-op. Societies (Urban) (2005) 5 Hukmi Chand v Jaipur Ice and Oil Mills Company,

SCC 632 AIR 1980 RAJ 155

20. K. Muniswamy v. K.

Venkataswamy, AIR 2001 Kant.

246

21. Tulk v. Moxhay (1848) 2 Ch. 774

Vested and Contingent Interest, Ss. 13-24, TPA. Kokilambal and Others v N. Raman, (2005) 11

Transfer to Unborn Persons, 22. Ma Yait v The Official Assignee SCC 234

Rule against Perpetuity. (1930) 32 BOMLR 125

23. Rajes Kanta Roy v Santi Debi AIR

1957 SC 255

7-8 Equitable Rules Ss. 38, 39, 41-43, 48-51, TPA. Patil, Yuvraj Dilip, Ostensible Ownership Vis a Vis

when rights Benami Transaction in India (December 20,

conflict 2012). Available at SSRN:

http://ssrn.com/abstract=2191951

Salient Features of the Benami Transactions

(Prohibition) Amendment Act, 2016

Transfer of Lis Pendens; Ss. 52 & 53 TPA. Would arbitration amount to lis pendens?

property under FradulentFraudulent Transfer. 24. Abdul Shukoor v. Arji Papa Rao

litigation, AIR 1963 SC 1150

Fraudulent 25. Guruswamy Nadar v. P. Lakshmi

Transfer Ammal (Dead) Through LRs. &

Ors., (2008) 5 SCC 796.

26. Jayaram Mudaliar v. Ayyaswamy,

AIR 1973 SC 569

27. Supreme General Films Exchange

Ltd v. Maharaja Sir Brijnath

Singhji Deo, AIR 1975 SC 1810.

Part Performance S. 53A, TPA

9 Sale, Exchange, Meaning; Difference; Sale Deed Ss. 54 – 55; 118 -121; 122-126. Ahmad, Tabrez, Comparative study of Gift under

Gift v. Agreement to Sell; 28. Vidyadhar v. Manikrao, AIR 1999 Islamic Law and Transfer of Property Law: Indian

Rights and Liabilities of Buyer SC 1441 perspective (September 11, 2009). Available at

and Seller. 29. Suraj Lamps Pvt. Ltd. v/s State of SSRN:

Haryana and another, 2011 (11) http://ssrn.com/abstract=1471926.

SC 438.

30. Satyawan v. Raghbir, AIR 2002

P&H 290

31. John Thomas v Joseph Thomas,

AIR 2000 Ker 408

32. Subhas Chandra v Ganga Prasad,

AIR 1967 SC 878

10 Lease,[IS1] License Meaning of lease; Types of Ss. 105 – 109. Kiran Wadhwa, Maharashtra Rent Control Act

lease; Overview of rent control 1999: Unfinished Agenda, EPW, Vol. 37.2002, 25,

Rights and duties of Lessor and legislations. p. 2471-2476

Lessee. 33. Sivayogeswara Cotton Press v. M.

Panchaksharappa, AIR 1962 SC

413

34. Dhanpal Chettiar v. Yesodai

Ammal AIR 1979 SC 1745

35. Shanti Devi v. Amal Kumar AIR

1981 SC 1550

36. Laxmidas Bapudas v. Rudravva

2001 (2) SCC 409

Differences between a Lease S. 52 Indian Easement Act.

and License 37. Associated Hotels of India Ltd. v.

R.N. Kapoor (AIR 1959 SC 1262)

38. Bharat Petroleum Corporation

Ltd. v Chembur Service Station,

Property Law Page 2

Ltd. v Chembur Service Station,

2011(4) SCALE 209, ¶18-20.

11-12 Mortgage and Introduction and Meaning; Ss. 58-98, 100.

Charge Nature; 39. Vidhyadhar v Manikrao AIR 1999

Essentials and Types; Right of SC 1441

Redemption and Clog on 40. Chaganlal v. Anantaraman, AIR

Redemption; 1961 Mad 415

Subrogation; 41. Mohiree Bibi v. Dharamdas

Marshalling. Ghose , (1903) ILR 30 Cal

42. Ganga Dhar v. Shankar Lal, AIR

1958 SC 770

43. Pomal Kanji Govindji v. Vrajlal

Karsandas Purohit, AIR 1989 SC

436 : (1989) 1 SCC 458

44. Shri Shivdev Singh & Anr vs

Sh.Sucha Singh AIR 2000 SC 1935

45. Sangar Gagu Dhula v. Shah

Laxmiben Tejshi, AIR 2001 Guj.

329

13 Adverse Possession S. 27 and Articles 64 and 65 of

the Limitation Act.

46. State Of Haryana vs Mukesh

Kumar & Ors on 30 September,

2011

14 Easements Definition, creation and Easements and Licenses Act.

extinction of easements

15 Revision

Property Law Page 3

Introduction

07 February 2018 08:38

There are two rights of cars, property rights and personal rights. A personal right over a property can be claimed against the Homework

person who has ownership rights. Personal rights can only be defended against the person who gave you the right. Property Under what section can I be penalised for

rights can be defended against the world. Property right is the right of ownership. burning my own property.

Property rights incentivise innovation when you know you get financial rewards. History has shown that land that is shared is

always plundered and destroyed. Tragedy of the Commons.

Example: Russia

When people don't have property rights and ownership they have control over no resources and therefore no power and they

thus are enslaved to their government. This leads to dictatorships abuse of power etc. Power is property. Property has

implications for freedom and democracy. Privacy and property rights are the two pillars for a free society. Governments contr ol

people either by attacking their privacy or their property.

Example: China's Big Data system/pride tokens , America's NSA

Europe's new data privacy right law

Clever Incentive Engineering

Pg. 5 general qualification for ownership

NMoore v. Regents of the University of California

https://www.casebriefs.com/blog/law/property/property-law-keyed-to-cribbet/non-traditional-objects-

Clarke%2c and-classifications-of-property/moore-v-regents-of-the-university-of-california-2/2/

Alison & P... The Courts and Legal Systems around the world want to preserve property rights and innovation

The state makes it illegal to use your body, your property in certain ways. Such as prostitution, suicide , organ selling etc.

Title Co-relations Opposite

Right Duty No-right

Privilege No-right Duty Some

Power Liability Disability Fundame...

Immunity Disability Liability

Property Law Page 4

Constitutional Law and Property

07 February 2018 10:00

Namita Wahi, Land Acquisition, Development and the Constitution

When awarding compensation it is not only monetary it is also the non-monetary aspects that have

to be given . How restrained is 'public purpose.'? The new law , has it put in consent? Whether

consent is needed for taking the land over? If you want to understand the power dynamics between

the state and the people, look at the private property rights .

Constitution

Article 19(1)(f) guaranteed to all citizens the fundamental right to ‘acquire, hold and dispose of

property.’ Article 19(6) made the right subject to ‘reasonable restrictions in the public interest’ by

the federal and state legislatures. Article 31 of the Constitution provided that any state acquisition of

property must only be upon enactment of a valid law, for a public purpose and upon payment of

compensation. Article 31 codified what is often described in political and legal parlance as the

‘eminent domain’ power of the state.

The paradox implicit in guaranteeing a fundamental right to property, while simultaneously

embarking on a socialist developmental project of land reform and state planned industrial growth,

predictably resulted in tensions between the legislature and the executive on the one hand, that

sought to implement this development agenda, and the judiciary on the other, which enforced the

fundamental right to property of those affected.

The following decades saw conflict between Parliament and the Supreme Court, with the court

invalidating acquisition laws for violating the fundamental right to property and Parliament

responding with numerous amendments to the Constitution that redefined property rights. This

conflict culminated in the 44th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished the fundamental

right to property in 1978. The same amendment however, inserted Article 300A in the Constitution,

which provided that no person shall be deprived of his or her property without the authority of a

valid law

There have been attempts to repeal the act and replace it with Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and

Resettlement Bill 2011 which is currently pending in Parliament because of land conflicts.

Land Acquisition Act 1894

Purpose for which land may be acquired: Section 3(f), public purpose - inclusive definition which SC

has held will be judicially determined as time changes. Section 39, land may be used by companies if

the work is likely to prove useful to the public

Procedure: The procedure for acquisition of land includes notification of land to be acquired

(Section 4), hearing of objections (Section 5A), final declaration of acquisition (Section 6) and

payment of compensation (Sections 23 and 24)

All disputes are to be settled in civil courts (Section 18).

Compensation: Section 23(1) of the act further provides that compensation for land acquisitions

must be computed at the market value of the land acquired.

Problems with it: 1. recognises right of only title holders 2. inclusive definition of public purpose

which SC said was elastic 3. compensation as fair equivalent of the value of land (exclusion of judicial

review by Parliament) 4. procedure of land acquisition (5. state/central conflicts in principles of

compensation)

Land Acquisition Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill

1.change in definition of persons interested but landless laborer's and cattle farmers etc. are

Property Law Page 5

1.change in definition of persons interested but landless laborer's and cattle farmers etc. are

affected families and they can't raise objections

2.Section 3 (za) contains a more detailed listing of ‘public purposes' but still has broad residuary

purpose as that which 'benefits the general public'

3. provisions for compensation both value and delays

4. while it can be used by private people, 80% of affected families should consent to acquisition. Also

private parties are bound by rehabilitation requirements of bill.

5. Social Impact Assessment for large projects but this committee has bureaucrats and not experts

The protections of rights and properties of Scheduled Tribes is instrumental. A major problem that

also needs to be addressed is arbitrary implementation of the Act which allows the government and

industrialists to collude and take advantage of smaller and minority groups. The removal of judicial

review provisions for land acquisition further prove this point.

1. Bela Banerjee v. State of West Bengal- AIR 1954 SC 170

Appeal from a judgement of the HC to hold certain provisions of the West Bengal Land Development

and Planning Act, 1948 unconstitutional and void. Enacted to provide provisions for settlement of

immigrants who migrated due to communal violence in East Bengal which provided acquisition for

public purposes including the aforementioned. The HC held the compensation provisions that

allowed the government to not pay the actual market value of the land on the date void. Proviso b of

Section 8 allowed the government to not pay compensation of more than the value of the land on

31-02-1946. Article 31(2) requires that the law provide compensation for property taken. Entry 42 of

List III allowed the state legislative discretion to determine principles of compensation.

The court said that the above while being true also means that the State must make principles that

will make the compensation a just equivalent of what the person is being deprived of. Full

indemnification of the expropriated owner is required by the Constitution. The methodology used

was arbitrary. It was pegged to a certain date's value of land and ignoring the value of the land as on

the date of acquisition cannot be regarded as compliance in the letter and spirit of Article 31(2). The

fixing of an anterior date may not be arbitrary. Any principle for determining compensation that

denies the owner increment in value cannot result in the ascertainment of the true equivalent of the

land appropriated. Whether such principles take into account all the elements which make up true

value of property appropriated and exclude matters which are neglected , is a justiciable issue to be

adjudicated by the court.

The latter part of proviso (b) to Section 8 was held unconstitutional and void.

2. Vajravelu Mudaliar v. Special Deputy Collector- AIR 1965 SC 1017

Filed under Article 32 challenging constitutional validity of the Land Acquisition (Madras

Amendment) Act, 1961. Through a government notification, the plaintiffs lands were sought to be

acquired by the state under the Land Requisition Act 1894 for development of neighborhoods in

Madras. The respondent though another notification said that he was authorized to take those lands

under Section 17(4) because there was an urgency. Therefore application of Section 5(a) had been

dispensed with. The act in question was enacted for laying down principles for compensation

different from those under the 1894 Act.

The petitioner was to be paid compensation under the Land Acquisition (Madras Amendment) Act,

1961 and this Act the petitioner holds offends Articles 14, 19 and 31(2). The respondents argued that

were saved by Article 31-A. Even if not, the provisions did not offend either of the aforementioned

provisions. They also contended that after the (Constitution Fourth Amendment) Act 1955 the

expression "compensation" carried a different meaning than that given to it in the Bela Banerjee

case and therefore the amount given the impugned act is justiciable.

Article 31-A lifts the ban on the State to fix compensation and acquire land for public purpose as

under Article 31(2) and 2-A to enable the State to implement the pressing agrarian reforms. This

object of the Constitution is implicit in Article 31-A. Therefore, Article 31 A doesn't apply since the

Property Law Page 6

object of the Constitution is implicit in Article 31-A. Therefore, Article 31 A doesn't apply since the

Amending act is not in reference to agrarian reform but also housing schemes. Bela Banerjee laid

three points. Namely 1. the compensation under Article 31(2) shall be a 'just equivalent' of what the

owner has been deprived of 2. the principles which the legislature can prescribe are only principles

for ascertaining 'just equivalent' 3. if not, if all relevant elements are not taken into consideration, it

is justiciable. This is before the Fourth Amendment. This law accepts the meaning of 'compensation'

in Bela Banerjee. However, the 'just equivalent' cannot be questioned by the court on the basis of

adequacy of compensation is a reasonable interpretation of the new amendment. If the

compensation is based on principles that are irrelevant to the value of the property at or about the

time of acquisition the legislature can be said to have committed a fraud on power and therefore the

law is bad. It is use of protection of Article 31 in a manner which the article hardly intended.

Applying the doctrine of fraud on power or colorable legislation, the legislation cannot make a law in

derogation of Article 31(2). It can only make a law on acquisition or requisition by providing for

compensation in the manner prescribed in Article 31(2) Constitution. If the legislature provides for

compensation but in effect and substance takes away a property without paying compensation or

paying illusory compensation for it, it will be exercising power which it does not possess. If it makes

compensation laws that do not relate to the property acquired or to the value of such property at or

within a reasonable rate to the property acquired etc. one can easily hold that the legislature made

the law in fraud of its powers. The legal position is that if the question pertains to the adequacy of

the compensation it is not justiciable but if the compensation fixed or the principles evolved for

fixing it disclose that the legislature made the law in fraud of powers, the question is within the

jurisdiction of the court.

The court held that the Amending Act did not offend Article 31(2) of the Constitution since the third

principle mentioned which excluded the compensation being paid according to the potential value

of the land related to inadequacy of compensation and not fraud on power. The contention that it

was violative of Article 14 was accepted and the Amending Act was declared void.

3. Union of India v. Metal Corporation of India Ltd- AIR 1967 SC 634

The appeal was about the validity of the Metal Corporation of India (Acquisition of Undertaking) Act

1965. The Act which allowed the government to take over the Corporation was contested by the

plaintiff to be void as it violated the provisions of Article 31. The Act in question allowed for

valuation of assets , specifically the machinery and equipment in two ways. One for those which

have not been used and are valued actual cost incurred by corporation and the second, the used

machinery and equipment would be valued at written-down value determined in accordance with

provisions of the Income Tax Act, 1961. Negating a contention of the respondent the court said that

if all the principles do not provide for the just equivalent of all the parts of the undertaking, the sum

total cannot obviously be a just equivalent of the undertaking.

For unused machinery in good condition the cost value of it in purchase is much lesser than its value

in the open market now. For used machinery the written down value rule in Income Tax Act is not

relevant. An artificial rule evolved for tax purposes has no relevance in asset value. The principle

must be such as to enable the ascertainment of its price at or about the time of its acquisition. The

judgement said firstly that the principle being used for compensation was not viable because the

cost of machinery due to technology increases. The Metal Corporation of India is arguing that

depreciated value is not a relevant standard to selling the machinery in the open market or the

actual value of the machine. Therefore the income tax rules which are used to determine profit and

therefore value machines and also require depreciation are not relevant for the case.

The right to question the methodology is not prevented by the 4th Amendment. The courts can only

challenge the compensation if the methodology is arbitrary and illusory. The court separated the

'compensation' and 'jurisdiction' parts of the provision. The law to justify itself has to provide for the

payment of a 'just equivalent' to the land acquired or lay down principles which will lead to the

result. If the principles laid down are relevant to the fixation of compensation and are not arbitrary,

the adequacy of the resultant product cannot be questioned in a Court of law. The validity of the

principles judged by the above tests, falls within the judicial scrutiny and if they stand the tests, the

adequacy of the product falls outside its jurisdiction. Judged by the tests in Bela Banerjee and

Property Law Page 7

adequacy of the product falls outside its jurisdiction. Judged by the tests in Bela Banerjee and

Vajravelu v. Special Deputy Collector the principles for fixation of value have not provided for

'compensation' within the meaning of Article 31(2) of the Constitution and therefore is void.

4. State of Gujarat v. Shantilal 1969(1) SCC 509

This case deals with Bombay Town Planning Act 1955. The payment here was made on the basis of

the market value if the land on the date of declaration of intention to make a scheme and there was

no principle for compensating an owner of land to whom reconstituted plot was allotted.

Shah.J:

Clause (1) of Article operates as a protection against deprivation of property save by authority of law

which must be valid law. Clause (2) guarantees that the property shall not be acquired save by

authority of law providing for compulsory acquisition and either fixes the amount of compensation

or specifies principles on which it is given. If the conditions for compulsory acquisition are fulfilled,

the law is not liable to be questioned on the grounds that it is not adequate. Further Clause 2-A is a

definition clause for compulsory acquisition and reacquisition. The Act does not violate Article 31

because the specified principles on which compensation is to be determined are given. The word

'compensation' here means anything given to make things equivalent.

If the quantum of compensation is not justiciable in court then the principles will not be open for

challenge on the indefinite plea that the compensation determined by the application of the

principles is not a just equivalent or fair compensation. That principles cannot be challenged on the

basis of inadequacy of compensation does not mean that principles that are illusory and grant a

character of arbitrariness and defeat constitutional guarantee can be upheld. Principles can be

challenged on the ground that they are irrelevant to the determination of compensation. There is

justness involved in assessing what the compensation ought to be. Observations in P.Vajravelu

Mudaliar's case about Article 31(2) said to the contrary, that attack on the principles is excluded only

when is found on a plea of inadequacy of compensation would be giving a restricted meaning to

Article 31(2) practically nullifying the amendment. The observations of Article 31(2) were not

necessary in deciding the case and therefore they cannot be regarded as binding. Metal Corporation

of India Limited 's case was wrongly decided and overruled as the compensation was not illusory and

the principles used were wrong.

Hidyatullah:

The adequacy of compensation which is illusory or proceeds upon principles irrelevant to its

determination should not be questioned after the amendment of the Constitution. The amendment

was expressly made to get over the effect of earlier cases which had defined compensation as just

equivalent. Enactment of a rule determining payment or adjustment of price of land of which the

owner was deprived by the scheme estimated on the market-value on the date of declaration of the

intention to make a scheme amounted to specification of a principle of compensation within the

meaning of Article 31(2)

5. R.C. Cooper v. Union of India, 1970 (2) SCC 298 (Bank Nationalization case)

(Page 35-40)

This case concerns the constitutional validity of the Banking Companies (Acquisition of Transfer of

Undertakings) Act 1969. The petitioner held shares and had accounts in certain banks and was also a

director in one of these banks. It was held that the Act and Ordinance were invalid and action taken

or deemed to be taken in exercise of powers under the Act were unauthorised. Under the scheme of

determination of compensation total amount payable to banks was only a fraction of the value of

their net assets and compensation was not easily available to banks. The compensation was neither

just nor proportionate. Act was liable to be struck down as there was infringement of guarantee of

freedom of trade, commerce and intercourse under Article 301.

Article 31(1) and (2) arise out of limitations placed on the authority of the State by law to take over

the individuals property. If the acquisition is for public purpose, substantive reasonableness of the

restriction which includes deprivation may, unless otherwise established be presumed but enquiry

into reasonableness of the procedural provisions will not be excluded. A provision to satisfy Article

Property Law Page 8

into reasonableness of the procedural provisions will not be excluded. A provision to satisfy Article

31 should either be 1. for public purpose 2. have fixed amount of compensation or specify principles

in order to fix compensation. Jurisdiction of court to question the law on the ground of adequacy of

compensation is expressly excluded. The court reiterated Shantilal where it said that a challenge to a

statute that the principles specified by it do not award a just equivalent will be in clear violation of

the Constitutional declaration that inadequacy of compensation provided is not justiciable. What is

fixed as compensation by statute, or by the application of principles specified for determination of

compensation is guaranteed: it does not mean however that something fixed or determined by the

application of specified principles which is illusory or can in no sense be regarded as compensation

must be upheld by the Courts, for, to do so, would be to grant a charter of arbitrariness, and permit

a device to defeat the Constitutional guarantee.

"There was apparently no dispute that Article 31(2) before and after it was amended guaranteed a

right to compensation for compulsory acquisition of property and that by giving to the owner, for

compulsory acquisition of his property, compensation which was illusory, or determined by the

application of principles which were irrelevant, the Constitutional guarantee of compensation was

not complied with. There was difference of opinion on one matter between the decisions in P.

Vajravelu Mudaliar's case(2) and Shantilat Mangaldas's case. In the former case it was observed

that the Constitutional guarantee was satisfied only if a just equivalent of the property was given

to the owner: in the latter case it was held that "compensation" being itself incapable of any

precise determination, no definite connotation could be attached thereto by calling it "just

equivalent" or "full indemnification", and under Acts enacted after the amendment of Article

31(2) it is not open to the Court to call in question the law providing for compensation on the

ground that it is inadequate, whether the amount of compensation is fixed by the law or is to be

determined according to principles specified therein.

Both the lines of thought which converge in the ultimate result, support the view that the principle

specified by the law for determination of compensation is beyond the pale of challenge, if it is

relevant to the determination of compensation and is a recognized principle applicable in the

determination of compensation for property compulsorily acquired and the principle is appropriate

in determining the value of the class of property sought to be acquired. On the application of the

view expressed in P. Vajravelu Mudaliar's case or in Shantilal Mangal's case. The Act, in our

judgment, is liable to be struck down as it fails to provide to the expropriated banks compensation

determined according to relevant principles."

6. KT Plantation v. State of Karnataka, (2011) 9 SCC 1

The Bench upheld the acquisition of properties owned by film actress Devika Rani and her husband

near Bangalore under the provisions of the Devika Rani Roerich Estate (Acquisition & Transfer) Act,

1996 and Karnataka Land Reforms Act, 1961. Public purpose was a pre-condition for deprivation of a

person of his property under Article 300A of the Constitution and the right to claim compensation

was also inbuilt in that Article. The purpose needs to be primarily public and not incidentally public.

The requirement of public purpose is invariably the rule for depriving a person of his property,

violation of which is amenable to judicial review. Acquisition of property for a public purpose may

meet with a lot of contingencies, like deprivation of livelihood, leading to violation of Article 21, but

that per se is not a ground to strike down a statute or its provisions. When a person is deprived of

his property, the State has to justify both the grounds which may depend on scheme of the statute,

legislative policy, object and purpose of the legislature and other related factors. Statute, depriving a

person of his property is, therefore, amenable to judicial review. Question of whether the purpose is

primarily public or not has to be decided on the basis of purpose and object of statute and policy of

legislation. Compensation must be 'just, fair and reasonable.' Statutes protected by Article 31A, 31B

and 31C would be amenable to challenge under Article 14 and 19 as part of the basic structure but

not Article 14 and 19 simpliciter.

Right to claim compensation cannot be read into List III Entry 42. No compensation or nil

compensation has to be justified by the State on judicially justiciable standards. While enacted 300

A parliament has only borrowed Article 31(1) i.e. the Rule of Law doctrine and not Article 31(2) i.e.

the doctrine of eminent domain. Article 300 A enables the State to put restrictions on the right to

Property Law Page 9

the doctrine of eminent domain. Article 300 A enables the State to put restrictions on the right to

property by law. The law has to satisfy the provisions of the Constitution. Acquisition of property for

public purpose may meet with a lot of contingencies, like deprivation of livelihood which may lead to

Article 21, but that per se is not a ground to strike down a statute or its provisions. The Act in the

present case is immune from challenge under Article 14 on the ground of arbitrariness and

unreasonableness. But if a statue violates rule of law or the basic structure of the Constitution it

would not be immune from the challenge.

Property Law Page 10

Types of Property

27 February 2018 14:11

“Immovable property” shall include land, benefits to arise out of land, and things attached to the

earth, or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth.

Section 3(26) of General Clauses Act 1897

Section 3 of TPA, talks about what involves "Immovable property"

TPA 1882

“immovable property” includes land, buildings, hereditary allowances, rights to ways, lights, ferries,

fisheries or any other benefit to arise out of land, and things attached to the earth, or permanently

fastened to anything which is attached to the earth, but not standing timber, growing crops nor

grass;

Requirements for immovable property to validly be transferred:

Needs to be in writing

Needs to be attested and executed

Needs to be registered

Transfer of Property only happens during the lifetime. So will and succession are not included.

Operation of law such as insolvency, forfeiture, court order etc. Transfer of Property does not apply.

Property is a bundle of rights. On top of the pyramid are property rights and at the bottom we have

personal rights. The difference b/w the two is that property rights can be defended against anyone

in the world. At the top of the pyramid there is absolute ownership. Property rights run with land.

In a lease, the landlord gives the lease an interest in the property. If someone say a worker can come

into the property and work there for a while till say 3 pm, then this is a personal right and this does

not run with property. If it’s a license it’s a personal right if it is a lease it’s a property right.

Only immovable property comes into the purview of the Transfer of Property. Whether ownership

passes or not, one needs to know whether there was a valid transfer of property. Therefore, one

needs to know the rules that apply.

The distinction between movable and immovable property

1. Ananda Behera v. State of Orissa (1955) 2 SCR 919

The dispute is about fishing rights in Chilka lake which was once the estate of the Raja of Purikud.

The Orissa Esatates Abolition Act, 1951 vested the estate in the State of Orissa. The petitioners had

through contracts obtained licenses for catching and appropriating the fish from the fisheries. The

lake was immovable property that had been transferred to the State of Orissa who now have all the

rights that owners have. The petitioners claim the right to obtain future goods under the sale of

Goods Act and this is purely a personal right arising out of contract to which the State of Orissa is not

a party. What was sold was the right to catch fish. The right to fish is immovable property because it

is a benefit arising from the property or a profit a pendre that is the lake.

Section 3(26) of the General Clauses Act defines "immovable property" as including benefits that

arise out of land. It follows that fish is immovable property as under Transfer of Property Act

because it cannot be determined by the definition of "immovable property" in the aforementioned

and thus the General Clauses Act has to be looked at. Because of Section 54, a sale or transfer of

immovable property requires writing and registration. The sale of the fish would constitute as

transfer of property, however they would have to follow the requisites of the Transfer of Property

Act. They did not as the contract was an oral contract. Therefore there is no interest or title in the

Property Law Page 11

Act. They did not as the contract was an oral contract. Therefore there is no interest or title in the

petitioners.

Fishing is a right to acquire a future good. What was sold was the right to catch fish. The contract

was for two types of rights. The right to enter the property and the right to fish and carry away the

fish. The former is a personal right and the latter is an immovable property right. Personal rights do

not devolve with the property and therefore the State has no liability.

(Paragraph 9, 10 ,12 and 13)

2. Shantabai v State of Bombay, AIR 1958 SC 532

There was no transfer of proprietary right, they only had a license to enter and get wood. A

transaction like this is the right to enter the land and the grant to cut the trees and carry away the

wood. Trees have to be fit for purpose to be cut down and felled and their trunk used as timber for

sale. The question is whether it is immovable property. Section 3(26) of the General Clauses Act says

it is. However, Transfer of Property Act in Section 3 says it is not. A standing timber must be a tree

that can be looked at as timber for all practical purposes. If not, it is a tree because it will continue to

draw sustenance from the soil. Justice Bose says that those trees that have attained a certain

amount of maturity and girth and are ready to be cut in the immediate future and are standing

timber and they fall on movable property. Those trees which aren't ready to be cut as timber will be

trees and immovable property. The three types of trees 1 . That reached maturity that she could cut;

standing timber 2. that reached maturity that she could not cut; standing timber 3. that haven't

reached maturity and thus she did not have the intention to sell it; it was movable property. If the

tree stooped drawing sustenance from the soil and has been cut reasonably early then it is ready to

be cut. The grant is also for trees that are not ready to cut reasonably early. These for present

purposes are trees. They would thus be movable property. The remaining are immovable property

and under the Transfer of Property Act are unregistered.

The unregistered contract gave her personal rights, not proprietary right. The contract was between

the petitioner and her husband. Being unregistered it does not affect the immovable property or

give her any right to any share of interest . The document is in the nature of the license and that

being extinguished as soon the land was appropriated, the petitioner can ask for compensation. If

not, and if the petitioner has an interest in the property it is a profit a pendre and since the

document has not been registered, the Transfer of Property Act doesn't apply. The State does not

have to honor the personal rights arising out a contract that it was not a party to. The rights being

personal don't run with the property.

3. Suresh Chand v. Kundan (2001) 10 SCC 221

When the land was agreed to be sold to the appellant there were no trees and during the litigation

period if 25 years the plants and saplings grew into trees. The petitioner is disputing the fact that the

respondent said that the land has been sold and not the trees on the land. Trees are immovable

property and are benefits out of land. The court says that if one is selling land then everything that is

attached to the land goes with the land unless there is an intention to the contrary in accordance

with Section 8 of the Transfer of Property Act.

4. Duncan Industries Ltd. v State of Uttar Pradesh, (2000) SCC 633

The question of whether the machinery embedded in Earth is movable property depends upon the

facts and circumstances of the each case and the court is to take in intention of the party, when it

decided to embed the machinery and if such embedding was made temporary or permanent. The

conveyance deed acc. to the respondents gives both the land and machinery but the stamp duty was

paid only for the land. The plaintiffs said that the machine wasn't a part of the value of the land.

However, an artificial distinction cannot be made between the land and the machinery permanently

attached to it. The machines embedded into land were immovable property because that was the

specific intention of the parties. A fertilizer plant cannot be sold without the machinery. The

machinery was not embedded in such a way as to remove the same for the purpose of sale at any

Property Law Page 12

machinery was not embedded in such a way as to remove the same for the purpose of sale at any

point of time. It's physically in the land and the land cannot be used without machines. It should

have been included in stamp duty free because it is immovable property and it needs to be

calculated in the valuation of the land. The contract showed that what is being sold is a fertilizer

business on an 'as is where is basis'. It is clear therefore it is not only for land but the entire business

that included plant and machinery. The conveyance deed being only for land is for the purpose of

paying less registration fee by showing less market value. Therefore the authorities are justified in

taking into consideration the value of the plant and machinery also. The appellants contented that

the valuation confirmed by the revisional authority was not based on any material and the finding

was arbitrary. Once we are convinced that the method adopted by the authorities for the purpose of

valuation is based on relevant materials then this Court will not interfere with such a finding of fact.

5. Triveni Engineering & Industries Limited v. Comm. of Central Excise (2000) 7 SCC 29

For excise duty, the goods have to be manufactured in India and be excisable. The appellants deal in

turbo alternators which have two components. They put together a steam turbine and an alternator

to make a turbo alternator. The legal test for manufacturing is if something new comes into

existence or if the components can be used individually. These two products won't do the same job

as individual machines. This new product came into existence by the coupling of the two

components. They combine the two components ; the alternator and the turbine. In the instant

case, the appellants were, according to specified designs, combining steam turbine and alternator by

fixing them on a platform and aligning them. As a result of this activity of the appellants, a new

product, turbo alternator, came into existence which has a distinctive name and use different from

its components. The two components were fixated in the ground. The test of permanency is if the

chattel can be picked up and taken to another place then it is movable but if it needs to be broken

down into parts and then taken away then it is immovable property. If a property needs to be

charged using excise, both mobility and marketability needs to be proved. Marketability means if it

can be picked up and taken to the market. Intention and the factum of fastening; that is the

intention of the sale and whether the machine has been fastened. The test of permanency fails

because the final product cannot be treated as one and the components have to be taken apart and

the foundation bolts have to be undone. The marketability test fails because it cannot be taken as it

is and sold in the product. The turbo alternator needs to be permanently fastened to function and

thus it is immovable property. The intention to use this is to fix this to Earth and use it permanently.

Immovable property cannot be excisable.

Turbo Alternator is not excisable goods.

Property Law Page 13

Registration and Stamp Duty

13 March 2018 06:48

Stamp duty is a tax charged by the government on the sale of property. It is designed to cover the

cost of the legal documents for the transaction. The main document is the ownership title of the

property and a search to ensure you are buying the property from the right person.

Registration Act , 1908

The Registration Act, 1908, was enacted with the intention of providing orderliness, discipline and

public notice in regard to transactions relating to immovable property and protection from fraud and

forgery of documents of transfer. This is achieved by requiring compulsory registration of certain

types of documents and providing for consequences of non-registration. In other words, it enables

people to find out whether any particular property with which they are concerned, has been

subjected to any legal obligation or liability and who is or are the person/s presently having right,

title, and interest in the property. It gives solemnity of form and perpetuate documents which are of

legal importance or relevance by recording them, where people may see the record and enquire and

ascertain what the particulars are and as far as land is concerned what obligations exist with regard

to them.

Section 17

Section 17 embodies the documents that need to be compulsorily registered. Under Section 17(b)

instruments which transfer rights in immovable property require registration. Under Section 53A,

part performance of sale contract is allowed with delivery of possession and under Section 17(1A),

to give effect to Section 52A, such documents need to be registered after the Amendment Act 2001.

Section 18

Documents used for transfer of immovable property of value less than 100 Rs. have optional

registration under this Section.

Section 49

Documents which are required to be registered due to non-registration cannot be used as evidence

of transaction and do not allow interference on such immovable property.

Indian Stamp Act 1899

The Indian Stamp Act of 1899 (2 of 1899), is an in-force Act of the Government of India for the charging

of stamp duty on instruments recording transactions.

1. Suraj Lamps Pvt. Ltd. v State of Haryana, 2011 (11) SC 438.

The 2009 order in the Suraj Lamps brought to light the use of SA/GPA/Will transactions to avoid

registration of sales. The court had referred the case to the Solicitor General to look into the case.

Briefly, the Suraj Lamp (2012) Judgement is but a clarification of the previous Suraj Lamps case

(2009). The issue was whether SA/GPA/Will (registered or un-registered) transfer the title and

ownership interest in property as required under Transfer of Property Act (u/s 5 and 53A).

The modus operandi in such SA/GPA/WILL transactions is for the vendor or person claiming to be

the owner to receive the agreed consideration, deliver possession of the property to the purchaser

and execute the following documents or variations thereof through a sale agreement with a future

date for execution of documents, irrevocable power of attorney or general power of attorney to

transfer and special power of attorney to manage the property and A will bequeathing the property

to the purchaser (as a safeguard against the consequences of death of the vendor before transfer is

Property Law Page 14

to the purchaser (as a safeguard against the consequences of death of the vendor before transfer is

effected). These transactions are not to be confused or equated with genuine transactions where

the owner of a property grants a power of Attorney in favour of a family member or friend to

manage or sell his property, as he is not able to manage the property or execute the sale,

personally. These are transactions, where a purchaser pays the full price, but instead of getting a

deed of conveyance gets a SA/GPA/WILL as a mode of transfer, either at the instance of the vendor

or at his own instance.

The earlier order dated 15.5.2009, noted the ill-effects of such SA/GPA/WILL transactions (that is

generation of black money, growth of land mafia and criminalization of civil disputes) as under:

"Recourse to `SA/GPA/WILL' transactions is taken in regard to freehold properties, even when there

is no bar or prohibition regarding transfer or conveyance of such property, by the following

categories of persons:

(a) Vendors with imperfect title who cannot or do not want to execute registered deeds of

conveyance.

(b) Purchasers who want to invest undisclosed wealth/income in immovable properties without any

public record of the transactions. The process enables them to hold any number of properties

without disclosing them as assets held.

(c) Purchasers who want to avoid the payment of stamp duty and registration charges either

deliberately or on wrong advice. Persons who deal in real estate resort to these methods to avoid

multiple stamp duties/registration fees so as to increase their profit margin.

Whatever be the intention, the consequences are disturbing and far reaching, adversely affecting

the economy, civil society and law and order. Firstly, it enables large scale evasion of income tax,

wealth tax, stamp duty and registration fees thereby denying the benefit of such revenue to the

government and the public. Secondly, such transactions enable persons with undisclosed

wealth/income to invest their black money and also earn profit/income, thereby encouraging

circulation of black money and corruption. It leads to an real estate mafia, for example in situations

when price of the land rises considerably and the buyer wants to sell the land. It finally, makes

verification and identification of title difficult.

There cannot be sale by execution of a power of attorney nor can there be a transfer by execution of

a power of attorney agreement of sale and a power of attorney and will. These kinds of transactions

have evolved to prevent paying stamp duty and registration charge on deeds of conveyance, to

avoid payment of capital gains on transfers, to invest black money and to avoid payment of

unearned increases. This has effects such tax evasion, black money and corruption, repeated sale of

the same land etc. Amendments to the Stamp Duty Act and Registration Act requiring registration

and stamp duty that were brought about to reduce the ill effects saw recourse to SA/GPA/Will

transactions. When a property is transferred via general power of attorney, the title deed is not

transferred. The government requires stamp duty and registration during usual sale agreements.

Using power of attorney, sale can be done without stamp duty or registration. This is why the title

deed is not transferred. As those sales done through power of attorney don't require stamp duty or

registration, this involves black money , tax evasion etc. On the same plot of land it is possible to give

multiple general power of attorneys because it is not registered and nobody knows.

One solution , as seen by the actions of the State of Haryana is reduction of stamp duty. Making

stricter undervaluation rules also helps because most properties are sold undervalued in paper, with

the difference paid in case. In many States appropriate amendments have been made whereby

agreements of sale acknowledging delivery of possession or power of Attorney authorizes the

attorney to `sell any immovable property are charged with the same duty as leviable on conveyance.

Scope of SA

Section 54 of TP Act makes it clear that a contract of sale, that is, an agreement of sale does not, of

itself, create any interest in or charge on such property.

In Rambhau Namdeo Gajre v. Narayan Bapuji Dhotra [2004 (8) SCC 614] this Court held:

Property Law Page 15

"Protection provided under Section 53A of the Act to the proposed transferee is a shield only against

the transferor. It disentitles the transferor from disturbing the possession of the proposed

transferee who is put in possession in pursuance to such an agreement. It has nothing to do with the

ownership of the proposed transferor who remains full owner of the property till it is legally

conveyed by executing a registered sale deed in favour of the transferee. Such a right to protect

possession against the proposed vendor cannot be pressed in service against a third party."

Any contract of sale (agreement to sell) which is not a registered deed of conveyance (deed of sale)

would fall short of the requirements of sections 54 and 55 of TP Act and will not confer any title nor

transfer any interest in an immovable property (except to the limited right granted under section

53A of TP Act)

Scope of GPA

General Power of Attorney is creation of an agency whereby the grantor authorizes the grantee to

do the acts specific therin on behalf of the grantor which when executed are binding on the grantor.

It is not an instrument of transfer.

Scope of Will

A will is the testament of the testator. It is a posthumous disposition of the estate of the testator

directing distribution of his estate upon his death. It is not a transfer inter vivos.

The court reiterated that immovable property can be legally and lawfully transferred/conveyed only

by a registered deed of conveyance. Transactions of the nature of `GPA sales' or `SA/GPA/WILL

transfers' do not convey title and do not amount to transfer, nor can they be recognized or valid

mode of transfer of immoveable property. The courts will not treat such transactions as completed

or concluded transfers or as conveyances as they neither convey title nor create any interest in an

immovable property .They cannot be recognized as deeds of title, except to the limited extent of

section 53A of the TP Act. The court allowed for prospective application of the case given that many

people were misled to believing that SA/GPA/Will transactions were prospective. It encouraged

regularization by authorities and immediate registration.

Section 2(d)

Section 5

Transfer of Property Act applies to those transfers which occur between two living persons.

Therefore, transfer through a will does not come under the Transfer of Property Act. In futuro would

mean for example a reversionary interest in property. This means I have an interest in the future

possession of property.

A Contingent Interest and A Vested Interest

In Futuro

When there is a condition for one to get ownership of property and that is certain and there is

nothing left for you to do, but you have to wait for a certain event to happen, one has a vested

interest.

Section 6

The following property rights/interests cannot be sold. The chance to inherit a property. A woman

can sell her right to past maintenance but not future maintenance.

Section 8

Assumption that a transferee transfers all interests in property capable of passing unless a contrary

intention is expressed or implied.

Section 9

Under this unless provided by law, oral transfers are allowed.

Property Law Page 16

Under this unless provided by law, oral transfers are allowed.

2. V. N. Sarin v. Ajit Kr. Poplai AIR 1966 SC 432

V.N. Sarin is a tenant who lives in HUF Property. Ajit Kumar Poplai owns the property after partition

where Sarin lives. The three members of this undivided Hindu family partitioned their coparcenary

property on May 17, 1962, and as a result of the said partition, the present premises fell to the share

of respondent No. 1. The appellant V. N. Sarin had been inducted into the premises as a tenant by

respondent No. 2 before partition at a monthly rental of Rs. 80. After respondent No. 1 got this

Property by partition, he applied to the Rent Controller for the eviction of the appellant on the

ground the he required the premises bona fide for his own residence and that of his wife and

children who are dependent on him. To this application, he impleaded the appellant and respondent

No. 2.

The appellant contended that Respondent No.1 got the suit by partition, then it was acquisition by

transfer as under S.14(6) and made the suit incompetent. It provides that where a landlord has

acquired any premises by transfer, no application for the recovery of possession of such premises

shall lie under sub-section (1) on the ground specified in clause (e) of the proviso thereto, unless a

period of five years has elapsed from the date of the acquisition. It is obvious that if this clause

applies to the claim made by respondent No. 1 for evicting the appellant, his application would be

barred, because a period of five years had not elapsed from the date of the acquisition when the

present application was made. The appellant also contended that the respondent was not his

landlord and that his use was not bona fide but these two were negated by the Punjab High Court.

The issue therefore was whether co-parcenery property can be called 'transfer' as under the Delhi

Rent Control Act, 1958.

The court examined the objective of Section 14(6).It seems plain that the object which this provision

is intended to achieve is to prevent transfers by landlords as a device to enable the purchasers to

evict the tenants from the premises let out to them. If a landlord was unable to make out a case for

evicting his tenant under s. 14(1)(e), it was not unlikely that he may think of transferring the

premises to a purchaser who would be able to make out such a case on his own behalf; and the

legislature thought that if such a course was allowed to be adopted, it would defeat the purpose of

s. 14(1).

Community of interest and unity of possession are the essential attributes of coparcenary property;

and so, the true effect of partition is that each coparcener gets a specific property in lieu of his

undivided right in respect of the totality of the property of the family. Having regard to this basic

character of joint Hindu family property, that each coparcener has an antecedent title to the said

property, though its extent is not determined until partition takes place. He already owned it , just

the nature of rights changed.

The appellant contended that partition was a transfer for S.53 of TPA according to judicial decisions.

The argument is that if it is 'transfer' under TPA it should be so under the Delhi Rent Control Act.

'Convey' means to give someone legal ownership of something he did not have before. It is not

conveyance as under Section 6, and therefore it is not transfer. That this was transfer as per Section

14(6) of the Delhi Rent Control Act was a contention by the respondent that was rejected by the

court taking into consideration the objective of Section 14(6). Basically , this section requires waiting

for 5 years in order to file a bona fide eviction petition. The court said that before partition, the co-

parceners only have an unspecified interest , but an interest nonetheless. The object of the Act is for

protection of property rights of strangers. But here, Arjit Kumar Poplai already had an interest in the

property. Therefore, he could file the eviction petition.

3. Kenneth Solomon v. Dan Singh Bawa, AIR 1986 Del 1

The tenant who was a lessee under Dan Singh Bawa bequeathed in her will all her movable and

immovable properties to her nephew who is the appellant in this case. On the tenant's death, the

landlord sought eviction under proviso b of Section 14(1)b of the Delhi Rent Control Act, 1958 on the

allegation that she had left no heir and had in her lifetime parted with the property without consent

of the landlord. The Delhi Rent Control Act requires consent of the landlord before transfer of lease.

Property Law Page 17

of the landlord. The Delhi Rent Control Act requires consent of the landlord before transfer of lease.

The appellant said that the tenancy rights had only devolved on him through the will which was not

parting of possession. Does the act of transfer of lease by writing a will amount to parting with the

tenancy rights without taking consent of the landlord as required under the Delhi Rent Control Act?

The expression "parted with possession", Therefore, means giving the legal possession acquired

under the lease to a person who was not a party to the lease agreement. Undoubtedly, there must

be vesting of possession of the tenancy premises by the tenant in another person by divesting

himself not only of physical, possession but also of a right to possession. The court held that the

process of parting with possession starts on the execution of the will but matures only on the death

of the testator. The tenancy rights deposed under the will would vest in the devisee immediately on

the death of the testator and this vesting would amount to parting with possession within the

meaning of proviso (b). The Transfer of Property Act excludes transfer by will, for a will operates

after the death of a testator.

No landlord can claim eviction, during the life time of the tenant, on the ground that the tenant had

made a will disposing the tenancy rights. It is for the simple reason that it can be revoked at any

time. By itself it does not vest the legal possession in the devisee. However, there is no escape from

the conclusion that by his voluntary act the tenant parts with the possession of the tenancy premises

though from the date of his death in case the will remains unrevoked. Dr. Sury by her act of

bequeathing the tenancy rights by means of the will in favor of the petitioner and his brother had

parted with possession within the meaning of proviso (b). The process stared in her life and the act

matured on her death. The landlord was, therefore, entitled to claim eviction. Anyway, it would've

passed on to the nephew through intestate succession.

Property Law Page 18

General Rules of Transfer

13 March 2018 07:02

It is a principle of economics that wealth should circulate and move freely, in order for the economy to get the greatest ben efit from it. The

Sections 10-18 on alienation provide that ordinarily there should be no restraints on alienation. 'Where wealth accumulates, men decay'

1.Muhammad Raza v. Abbas Bandi Bibi, (1932) I.A. 236

To settle a dispute in property two cousins got married, and executed an agreement for the property in dispute in lieu of the marriage. The

property in dispute was decided to be shared by the two wives in a limited capacity. They would have no power to transfer the property but

the ownership thereof as family property shall devolve on the legal heirs of both the wives, from generation to generation The condition was

put on the wives that the husband would manage the property and the ownership would be on the wife. They couldn't however sel l it to a

stranger or manage it. If on the part of the husband there is any act of neglect) or estrangement towards either of the wives, then, in that

case, the wife's only remedy will be to have the management of her share performed by the Government through the Court of War ds ; but

during the lifetime of Afzal Hasan neither of the wives shall have the power on her own authority to have the management of t he share which

is owned by her. Afzal Hussain thereafter duly married Sughra Bibi and died in 1872 childless, his first wife Fattina Begum h aving predeceased

him in 1871. Sughra Bibi took possession of her share in the properties, but had sold or mortgaged it all before her death, w hich occurred on

July 26,1914. Her transferees remained in undisturbed possession for nearly twelve years after her death. The respondents to the appeal

instituted a suit for the recovery of Sughra Bibi's share from the appellants to whom the alienations were made.

The respondents contended that Surga Bibi had only life estate without power of alienation and her heirs had vested interest in it on her

death. Their share was two -thirds. The present appeal, therefore, is concerned only with two-thirds of the property, and the rights of the

parties depend in the first instance on the validity of the alienations by Sughra Bibi, the title of the respondent, if these alienations were

invalid, not being disputed. She sold the property to a stranger and that stranger has enjoyed it for 12 years. The court assumed that the

settlement deed passed her ownership of property. The only thing that limited her was the restriction on alienation and manag ement. The

court says that the constraint was only partial and not absolute since she could still sell it to people in her family. T heir Lordships think that

the restriction was not absolute, but partial; it forbids only alienation to strangers, leaving her free to make any transfer she pleases within

the ambit of the family. The question, therefore, is whether such a partial restriction on alienation is so inconsistent with an otherwise

absolute estate that it must be regarded as repugnant and merely void . The settlement was not in the nature of transfer or conveyance. The

court said it would judge on the basis of justice, equity and good conscience, the three pillars of public policy. Family arr angements are to be

viewed upon on the lens of public policy. Even under Section 10 , partial constraint is allowed. In their Lordships' opini on Sughra Bibi had no

power to transfer any part of the properties to the appellants, and upon her death the respondent became entitled to the two -thirds share in

the properties which she claims.

2. Zoroastrian Co-operative Housing Society Ltd. V. District Registrar, Co-op. Societies (Urban) (2005) 5 SCC 632

The Zoroastrian Co-operative Housing Society was registered under the Bombay Co-operative Societies Act. One of the members of the

society sold the plot of land to the father of respondent 2 with the consent of the society on which he had constructed a re sidential building.

Respondent 2 became member of society on death of his father. Respondent 2 applied to society for permission to demolish bung alow and to

construct a commercial building in its place . Rejection of application by Society stating that bye laws of society did not p ermit commercial use

of land. Respondent 2 subsequently applied to society for permission to demolish bungalow and for construction of residential flats to be sold

to Parsis. Application allowed by society. Negotiations entered into by Respondent 2 with Respondent 3 a builder’s associatio n in violation of

restriction on sale of shares or property to a Non Parsi. Challenged by Society by filing a case before Board of Nominees. Bo ard held that

society could not restrict its membership only to Parsi Community. Rejection of application of Respondent 2.Tribunal held tha t bye law

restricting membership to Parsis was a restriction on right to property and was violative of Article 300 A. Writ petition - Dismissed by High

Court - Appeal to Supreme Court

The petitioners submitted that their fundamental right under 19(1)c was infringed. He also submitted that there was no absolu te restraint on

alienation to attract Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act and the restraint, if any, was only a partial restraint, valid in law. The

respondent said that Section 4 of the Act clearly indicated that no bye-law could be recognized which was opposed to public policy or which

was in contravention of public policy in the context of the relevant provisions in the Constitution of India and the rights o f an individual under

the laws of the Country. A bye-law restricting membership in a co-operative society, to a particular denomination, community, caste or creed

was opposed to public policy and consequently, the Authorities under the Act and the High Court were fully justified in rejec ting the claim of

the Society. Allowing appeal held that when a person accepts membership in a cooperative society by submitting himself to its bye laws and

places on himself a qualified restriction on his right to transfer property by stipulating that same would be transferred wit h prior consent of

society to a person qualified to be a member of society, it could not be held to be an absolute restraint on alienation offen ding Section 10 of

Transfer of Property Act. Hence finding of High Court that restriction placed on rights of members of a society to deal with property allotted

to him was invalid as an absolute restraint on alienation, held unsustainable and set aside. Not selling to anyone other than a Parsi does

amount to absolute restriction. It's partial restraint and therefore cannot be hit by Section 10. He becomes a member of the society by

devolution. He has voluntarily agreed to be a member of society. Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act cannot have any a pplication to

transfer of membership. Transfer of membership is regulated by the bye -laws. The bye-laws in that regard are not in challenge and cannot

effectively be challenged in view of what we have held above. Section 30 of the Act itself places restriction in that regard. There is no plea of

invalidity attached to that provision. Hence, the restriction in that regard cannot be invalidated or ignored by reference to Section 10 of the

Transfer of Property Act. It is difficult to postulate that such a qualified freedom to transfer a property accepted by a per son voluntarily,

would attract Section 10 of the Act. Moreover, it is not as if it is an absolute restraint on alienation. Respondent No. 2 ha s the right to transfer

the property to a person who is qualified to be a member of the Society as per its bye -laws. At best, it is a partial restraint on alienation. Such

partial restraints are valid if imposed in a family settlement, partition or compromise of disputed claims.

Property Law Page 19

The appellant is a housing society. It was stated that the essential feature of every housing society was at least that its h ouses formed one

settlement in one compact area and the regulation of the settlement rested in the hands of the managing committee of the soci ety. What is

relevant for our purpose is to notice that normally, the membership in a society created with the object of creation of funds to be lent to its

members, was to be confined to members of the same tribe, class, caste or occupation. It appears to us that unless appropriat e amendments

are brought to the various Cooperative Societies Acts incorporating a policy that no society shall be formed or if formed, me mbership in no

society shall be confined to persons of a particular persuasion, religion, belief or region, it could not be said that a soci ety would be disentitled

to refuse membership to a person who is not duly qualified to be one in terms of its bye -laws.

There is no transfer of property, it is getting inherited and the plaintiff consented to the society's laws and the Zoroastri an way of life.

3. K. Muniswamy v. K. Venkataswamy, AIR 2001 Kant. 246

The two brothers along with their father partitioned the property in 1969 under registered property deed where the property w as allotted to

the share of the father and mother with a stipulation that they should enjoy the properties during their life time in the man ner they like and

after their death, the property shall devolve in equal shares to the appellant and respondent, the two sons. In 1977, the par ents sold the

property under registered sale deed in favor of the respondent. After they died a suit is filed by the appellant seeking part ition of half share in

property contending that the parents had no absolute rights of alienation. The respondent contested the suit claimed exclusiv e title in the

property and also set up a plea of limitation that the suit is barred by time. Plaintiff filed a suit against the defendant s eeking partition of half

share in the suit property.

When a partition takes place b/w two or more members of a Hindu Joint family, it would be difficult to regard the partition a s involving a

transfer of any property from one co-sharer to the another. All that a partition brings about is a dissolution of the coparcenary and the

coparcenary property is transferred into more than one estate in severalty and each one of the persons who formed the Hindu joint family

becomes entitled to one of such estates to be exclusively enjoyed by him as its sole proprietor. Hence a condition in a partition deed to

which one of the parties agreed that he could not alienate certain properties but would enjoy them during his and his wife’s life tie cannot

be regarded as a void condition. Provisions of Section 10 of the Transfer of Property Act would not apply to family partition since there is

transfer of title, but on the ground of sound public policy any total restraint on right of alienation in respect of immovabl e property which

prevents free circulation would be held void. Partial restraint would be valid and binding.

It was held that interpreting the deed in the manner in which the Plaintiff wants, would be putting a total restraint on alie nation. The

question in the instant case, be whether the stipulation creates a limited estate or an absolute estate regarding the constru ction of deeds.

Partition deed emphasised that each of them get the property in their name and can do with it what they like. What is granted is therefore

absolute estate and not limited estate. Latter stipulation provides that after the demise of the parents, the plaintiff and the defendant shall

equally take the cannot override the clear terms of grant under petition. In the event of them dying intestate and that full or any part of the

property is available is left for intestate succession, in such a situation latter stipulation may come into effect otherwise not.

"In the instant case the partition deed is in Kannada. The plain reading of the partition deed suggests that " 'A', 'B' and ' C' schedule properties

are given to the shares of the respective parties with a emphasis added that each one of them should get their khata of the p roperty mutated

in their names and should enjoy the properties in the manner they like". This would give us no doubt and difficulty to apprec iate that what is

granted is a absolute estate and not a limited estate. May be that the latter stipulation provides that after the demise of t he parents, the

plaintiff and the defendant shall equally take the property. This cannot be interpreted to override the clear terms of grant under partition.

The restrictive covenants should be cautiously and carefully interpreted. The restrictions which are express would render no difficulty.

However, while implied restrictions if they are to be read into the terms of the document should be so clear and unambiguous to suggest the

one and only inference in favour of the restrictive covenant set up or pleaded otherwise, if stipulations are ambiguous, susc eptible to

contrary or alternative meaning, it would not be permissible to read into the said stipulation by inference restrictive coven ant. In the instant

case, it is possible to assume from the stipulation that an absolute estate is granted in favour of the parents in view of th e terms that they