Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hindu Law Assignment Muazzam

Hochgeladen von

Sandeep ChawdaOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hindu Law Assignment Muazzam

Hochgeladen von

Sandeep ChawdaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Special Marriage Act

and The Parsi Law of

Marriage

Muazzam Ali Khan

Roll No 36

Family Law Assignment

Submitted to – Kahkashan Mam

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

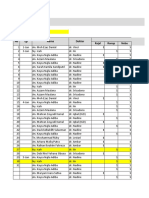

Index

1. Acknowledgement

2. The Special Marriage Act, 1954

2.1. Changes with the Emergence of Special Marriage Act in India

2.2. Legitimacy of children

2.3.Scope of the Act

2.4.Registration under the Special Marriage Act

2.5.Application of the Act

2.6.Matrimonial Relief under The Special Marriage Act, 1954

2.7. Void and Voidable Marriage

2.8. Force or Fraud

2.9.Divorce

2.10. Desertion

2.11. Conclusion

3. Parsi Marriage Act, 1865

3.1.Introduction

3.2. Requirements of a Parsi Marriage

3.3.Divorce

3.4.Irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground of Divorce

3.5.Divorce by Mutual Consent

3.6.Judicial Separation

4. Indian Divorce Act

5. Bibliography

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 1

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my special thanks of gratitude to my

teacher Prof. Kahkashan Y. Danyal ma‟am who gave me the

golden opportunity to do this wonderful project on the topic of

“Adoption and Maintenance”, which also helped me in doing a

lot of research and I came to know about so many new things I

am really thankful to her.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 2

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

The Special Marriage Act, 1954

In 1954 the Special Marriage Act was enacted by the Parliament to provide a special form of

marriage in certain cases. This law was made applicable to all citizens of India domiciled in the

country.

The marriages done under that Act were to be governed by the Indian succession Act of 1925

and not by the Hindu Law of Succession with regard to the questions of inheritance and

succession.

But this Act could not be socially acceptable as it did not give proper attention to traditional rites

and ceremonies which were considered very vital for a Hindu Marriage. To meet this

requirement, the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 was enacted which came into force on 18th May

1955.

Changes with the Emergence of Special Marriage Act in India

The position where the Parliament differed while enacting this act was the requirements that

previous codified laws had, for example Hindu Marriage Act provided that both the parties must

be hindus1, similarly the Muslim law of marriage requires both the parties to be Muslims.

If we look at the positive side of these marriages, we can find that they have added to our

national integrity. Unlike earlier times, nowadays people are attracted more to the opposite sex,

belonging to other castes and seldom end up considering the communal side of it. People from

higher castes tend to fall in love with people from lower castes and get married to them. What is

important is the amount of love and affection between them regardless of the status and

community they belong to. What we need to know is that Every Indian should change their

mindset about the caste system in our country and appreciate marriages between different

communities and religion. India is progressing with the increasing influence of education and

thus they must know about the advantages of Inter-caste marriages too (yes there are

advantages).

1

Section 5

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 3

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

These marriages encourage equality amongst the citizens and as a result of it people try to

interact more with each other and understand and respect each other and their differences. It sets

an example for other people that how love and respect can create a free and happy generation,

which is above the caste system and the evils of it.

Legitimacy of children

A marriage is said to be void, where the conditions mentioned in point no.4 are not met with, and

the children from such marriages who would have been legitimate if the marriage had been valid,

shall be legitimate, whether such child is born before or after the commencement of the Marriage

Laws (Amendment) Act, 1976 (68 of 1976), and whether or not a decree of nullity is granted in

respect of that marriage under this Act and whether or not the marriage is held to be void

otherwise than on a petition under this Act as mentioned in Sec.26 of the act.

The Special Marriage Act states that a marriage between two persons can be legalized, only

if the following conditions are satisfied at the time of marriage.

Neither of the two has a spouse living, at the time of the marriage.

Neither of the two is incapable of giving a valid consent to the marriage due to

unsoundness of mind.

Neither of the party has been suffering from mental ailments to such an extent, that they

are unfit for marriage and the procreation of children.

Neither party has been subjected to recurrent attacks of epilepsy or insanity.

At the time of marriage, the groom should be of twenty-one years of age and the bride

should be of eighteen years of age.

Both the parties are not within the degrees of prohibited relationship; provided where a

custom governing at least one of the parties permits of a marriage between them, such

marriage may be solemnized, notwithstanding that they are within the degrees of

prohibited relationship.

If the marriage is solemnized in the State of Jammu and Kashmir, both parties should be

the citizens of India, domiciled in the territories to which this Act extends.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 4

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

When a marriage is intended to be performed in accordance with the Act, the parties of

the marriage shall give notice in writing, in the Form specified in the Second Schedule to

the Marriage Officer of the district, where the marriage is going to be solemnized.

The marriage shall be solemnized after the expiration of thirty days of the notice period

that has been published under sub-section of the Act.

At least one of the parties going to perform the marriage should have resided for a period

of not less than thirty days, immediately preceding the date on which the notice for

marriage is issued to the registrar.

The marriage officer is bound to display the notice of the intended marriage, by affixing

a copy to some conspicuous place in his office.

If the marriage officer refuses to solemnize the intended marriage, then within a period of

thirty days of the intended marriage, either party can prefer an appeal to the District

Court, within the local limits of whose jurisdiction the marriage officer has his office.

The decision of the District Court, regarding the solemnization of the intended marriage,

shall be final.

Scope of the Act

The Special Marriage Act deals with inter caste and inter-religion marriages.

Inter-caste marriage is a marriage between people belonging to two different castes. Gone are

the days when people used to marry blindly wherever their parents decided them to. Now the

youth has its own saying and choice and they prefer getting married to someone who has a

better compatibility with them rather than marrying someone who belongs to their caste or

their religion. It is them who have to live with their partner for the entire life and thus caste or

religion is not a matter of utmost consideration at all now. Love is a beautiful emotion and it

should not be weighed with something like caste or religion. All religions are equal and

marriage amongst it should not be a big deal. Caste or religion is conferred on us by birth and

not by choice, then why are people of lower castes seen with shame and disdain? India is a

diverse country and things like this that happens here, is a thing of pity. Thus, the Special

Marriage Act is a special legislation that was enacted to provide for a special form of

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 5

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

marriage, by registration where the parties to the marriage are not required to renounce

his/her religion.

Any person married under the Special Marriage Act, must know about this important

provision of the Act. The parties cannot petition for divorce to the District court unless and

until one year has expired from the date of their marriage as registered in the marriage

books. But, in cases where the court is of the opinion that the petitioner has suffered

exceptional hardships or the respondent has shown exceptional depravity on their part, a

petition for divorce would be maintained, but if any misrepresentation is found on the part of

the petitioner to apply for divorce before the expiry of 1 yr, the court may if any order has

been passed, state the order to take effect only after the expiry of 1 yr, as mentioned in sec.

29 of the Act.

Registration under the Special Marriage Act –

For solemnization of marriage (Court marriage), nearness of the two gatherings is required after

accommodation of reports of issuance of notice of expected marriage. A duplicate of the notice is

stuck on the workplace see board by the Marriage Officer. Any individual may within 30 days of

issue of notice, m-card-declaration complaint to the expected relational unions. In such a case,

the Marriage Officer should not solemnize the marriage (between 9.30 to 1 pm) until the point

when he has chosen the complaint, inside 30 days of its receipt.

In the event that the Marriage Officer declines to solemnize the marriage, any of the gatherings

may m-card-authentication an interest inside 30 days to the District Court. In the event that no

protest is gotten, the Marriage Officer solemnizes the marriage following 30 days of the notice.

The two gatherings alongside 3 witnesses are required to be available on the date of

solemnisation of marriage. It is prudent to submit names of observers no less than one day ahead

of time, one of them be a legal counselor.

The marriage which has already been solemnized can be got registered at the office of Sub-

Divisional Magistrate in whose jurisdiction any of the husband or wife resides on any working

day.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 6

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

The following documents are required for registration -

1. Application form duly signed by both husband and wife.

2. Documentary evidence of date of birth of parties (Matriculation Certificate / Passport / Birth

Certificate).

3. Address proof of both the husband and wife. Adhaar card was being required for registration

too.

4. Affidavit by both the parties stating place and date of marriage, date of birth, marital status at

the time of marriage and nationality and that the parties are not related to each other within the

prohibited degree of relationship as per Hindu Marriage Act or Special Marriage Act as the case

may be.

5. Two passport size photographs of both the parties and one marriage photograph.

6. Marriage invitation card, if available.

7. If marriage was solemnized in a religious place, a certificate from the priest is required who

solemnized the marriage

8. In case one of the parties belong to other than Hindu, Budhist, Jain and Sikh religions, a

conversion certificate from the priest who solemnized the marriage(in case of Hindu Marriage

Act).

9. Two witness with photographs and copy of their PAN Card.

All documents excluding receipt should be attested by a Gazetted Officer

For registration of marriage in case of Hindu Marriage Act, verification of all the documents is

carried out on the date of application and a day is fixed and communicated to the parties for

registration. On the said day, both parties, along with a Gazetted Officer who attended their

marriage, need to be present before the SDM. The Certificate is issued on the same day.

However, in case of registration of marriage under the Special Marriage Act, presence of both

the parties is required after submission of documents of issuance of notice of intended marriage.

A copy of the notice is pasted on the office notice board by the SDM. Any person may within 30

days of issue of notice , file objection to the intended marriages. In such a case, the SDM shall

not solemnize the marriage until he has decided the objection, within 30 days of its receipt.

If the SDM refuses to solemnize the marriage, any of the parties may file an appeal within 30

days to the District Court. In case no objection is received, the SDM solemnizes the marriage

after 30 days of the notice. Both parties along with 2 witnesses are required to be present on the

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 7

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

date of registration of marriage who had attested the marriage. It is advisable to submit names of

witnesses at least one day in advance.

Application of the Act

This information is the most important one for every Indian to know as it is through this that they

can avail them. This Act covers marriages among Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Jains and

Buddhists. This act applies to every state of India, except the state of Jammu & Kashmir. This

Act extends not only to the Indian citizens belonging to different castes and religions but also to

the Indian nationals living abroad.

The conditions required to be followed for this special form of marriage is not very different

from the requirements of other normal marriages, which happen within the caste. These are the

conditions to be eligible for a marriage under this Act: –

The bridegroom must be at least 21 and the bride must be at least 18 years of age at

the time of marriage. This is the minimum age limit for a boy/girl to marry,

respectively.

Both the parties must be monogamous at the time of their marriage; i.e. they must be

unmarried and should not have any living spouse at that time.

The parties should be mentally fit in order to be able to decide for themselves e., they

must be sane at the time of marriage.

They should not be related to themselves through blood relationships; i.e. they should

not come under prohibited relationships, which will otherwise act as a ground to

dissolve their marriage.

Matrimonial Relief under The Special Marriage Act, 1954

The concept of a marriage being a nullity from the very beginning or being annulled subsequent

to the marriage is a concept of English origin from the times of the ecclesiastical courts which

exercised jurisdiction over every aspect of marriage. The ecclesiastical doctrine laid down that

marriage was not regarded as consummated if parties have not become one flesh by sexual

intercourse, and consequently if one of the parties was impotent and therefore unable to

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 8

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

consummate the marriage, he or she lacked the capacity to marry. Further, annulling a voidable

marriage was given retrospective effect. According to ecclesiastical law, a marriage was either

valid forever or never, in cases similar to the above, the marriage was declared void ab initio.

Such uncontrolled and unrestrained power in the hands of the religious leaders to declare

marriages void and bastardize the issue was a cause of great concern to the royal courts.

It was situations like this that lead to the question, whether laws which in spite of their

ecclesiastical authority character should force such arbitrary rules upon the common man. It was

as an answer to this question that laws were divided into (a) civil and (b) canonical. It was

further decided that a marriage in violation of the former would be void and latter would

voidable. It was also understood as a general principle that the validity could be questioned only

by the parties to a marriage and further that if one of the spouses died, such a question could

never arise.

Void Marriage

A marriage which arises on account of the fact that the parties have no capacity to marry, have in

fact married undergoing the requisite rites and ceremonies of marriage. Such a marriage is a

misnomer, a contradiction and is void ab initio. The essential feature of such a marriage is that

no legal consequences arise from it, i.e. no rights and obligation arise from it. Further since a

void marriage is no marriage at all, a decree of nullity is not necessary, as a decree merely makes

a judicial declaration of an existing fact.

Grounds of void marriage

A marriage performed in violation of absolute impediments is void. Under the SMA, a marriage

is void on the following grounds

Either party has a spouse living at the time of marriage.

Either party was at the time of marriage incapable of giving a valid consent in

consequence of unsoundness of mind or though capable of giving a valid consent, has

been suffering from mental disorder of such a kind or to such an extent as to be unfit for

marriage and procreation of children or has been subject to recurrent attacks of insanity.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 9

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

The bride was below 18 years in age and bridegroom was below age of 21 years at the

time of marriage

Parties were within the degree of prohibited relationship.

The respondent was impotent t the time of institution of the suit.

These grounds do not apply to marriages registered under the Act. The registration however

maybe cancelled on the following grounds:

Marriage was bigamous

Either party was an idiot or lunatic at the time of marriage

No valid ceremony of marriage was performed between the parties

One of the parties or both were under the age of 21 years at the time registration

Parties are within the degrees of prohibited relationship

Voidable Marriage

A voidable marriage is one which is valid until it is avoided. It can be avoided by a petition by

either party to a marriage if it violates conditions requisite to make a marriage valid. If, however

none of the parties petition for an annulment, it will remain valid. If one of the parties dies, the

validity cannot be questioned. The marriage will give rise to rights and obligations as long as it is

valid.

Grounds of voidable marriage:-

Under SMA, a marriage is voidable on the following grounds:

Non consummation of marriage on account of wilful refusal of the respondent to do so

Pre-marriage pregnancy of the respondent of which the petitioner was not the cause and

of which the petitioner was at the time of marriage ignorant, and marital inter course had

not take place with the consent of the petitioner after the knowledge of pregnancy and

further that the petition is presented within a year from the date of marriage

Petitioners consent was obtained by fraud or force, provided that the petitioner did not

live with the respondent as husband or wife after the discovery of fraud or cessation of

force and provided further that the petition was presented within one year of the

discovery of fraud or cessation of force.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 10

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Pre-Marriage Pregnancy

Pre-marriage pregnancy is a ground for voidable marriage under the SMA. This ground has its

origin in English and if often called a special kind of fraud. It has to be noted that this ground

talks about pre-marriage pregnancy lone and not pre-marriage unchastity. Even if the woman is

unchaste before the marriage and she had delivered an illegitimate child, the marriage could not

be avoided, since unchastity is not a ground of annulment of marriage . The conditions to be

roved here are,

1. Respondent was pregnant at the time of marriage

2. She was pregnant from a person other than the petitioner

3. Petitioner was not aware of respondent‟s pregnancy at the time of marriage

4. Petition must be presented within one year of the marriage under the SMA

5. No marital intercourse should take place with the consent of the petitioner after he had

known of wife‟s pregnancy

It is essential that all these conditions must be fulfilled before a petition can be filed. In case of

this particular ground the burden of proof is on the petitioner who must establish all the aforesaid

requirements. Also if the petition is not presented within the time limit specified under the Act, it

will become time-barred and the petitioner will be left with no remedy.

Fraud or Force

Broadly the ground uses the terms fraud and force. The SMA, 1954 uses the words coercion and

fraud. The requirements are:

1. Consent of the petitioner was obtained by fraud or coercion

2. Petition must be presented within one year of the discovery of fraud or cessation or

coercion

3. Petitioner must not have lived with the respondent, as husband or wife, as the case

maybe, after the discovery of fraud or coercion.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 11

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Force

Force i99n this context does not mean merely physical force it also includes mental agony and

torture. English authorities lay down that whatever owing to some natural weakness of mind or

on account of some fear, whether entertained reasonably or unreasonably, but nonetheless

entertained really, or when a party is in such a mental state that he finds it almost impossible to

resist the pressure, it will amount to duress as in such a case there is no real consent. This is what

coercion means under the SMA2

Strong advice and persuasion does not come within this definition. This is primarily because in

most cases of arranged marriage some element of persuasion is present and it would be absurd to

include all such cases as forceful and inclusive of coercion. Further it is also to be noted that for

the purpose of personal laws in India, the terms force, coercion, duress etc mean the same.

Fraud

It basically means situation sand circumstances as to show want of real consent to marriage. The

main element here is deceit. Unlike the Law of Contracts, misrepresentation either innocent or

fraudulent will not terminate the marriage. The important aspect here is respect to the fact that

has been fraudulently represented. If it a crucial element in the marital relation then it will affect

the marital relation. For example if there is a misrepresentation with respect to the ceremonies or

identity of the party. Under the Act the following are classified as fraudulent:

Fraud as to the nature of the ceremony

Shiram v. Taylor3 is a case where the parties went through with a ceremony of marriage though

the husband had no intention to regard it as a real marriage.

As to the identity of the person

C v. C 4 is a case where W married H in the erroneous belief that he was well known boxer

called Miller.

2

H v. H, (1954) P 258

3

(1942) New Zealand Law Review 35-49

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 12

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Concealment of disease

Amarnath v. Layyabat5i is a case where concealment of venereal disease lead to nullification of

the marriage. It was also held that some cases like syphilis will not be sufficient ground.

Concealment of religion or caste unchastity

Leelamma v. Dilip Kumar6 is an example where thewife married H under the impression that he

was a Christian belonging to an ancient family, when in fact he turned out to be an Ezhava.

Concealment of unchastity or illegitimate birth.

Harbhajan v. Brij7 is a case where H married W under the assurance that she was still a virgin. It

was however revealed that she had earlier given birth to an illegitimate child. The court refused

to grant the petition saying that this will be valid only if it can be proved that the husband

attaches great importance to her chastity

Several other factors, like concealment of age, financial status etc. Have aso been considered as

fraud in several other instances. The above list though not a comprehensive one deal with the

most important items.

Divorce

The matrimonial laws relating to divorce and separation in India have been greatly influenced by

the English matrimonial law viz., the Matrimonial Causes Act, 1857. Under the Act, the husband

can claim separation on the ground of wife‟s adultery, but the wife had to prove adultery

accompanied with bigamy, incest, cruelty, two years desertion and the like. This was typical of

the Victorian era. However modifications arose via the Matrimonial Causes Act, 1923, which put

both spouses at par and subsequently in 1937 when three more grounds were introduced into the

Act. The Indian Matrimonial Laws have closely followed these developments and have built

codes that closely follow the British model.

4

AIR I959 Cal 779

5

AIR I959 Cal 779

6

AIR 1964 Punj. 359

7

Section 24(1)(ii)

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 13

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

The Special Marriage Act, 1954 as amended under the Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act, 1976

recognises the following eight fault grounds for divorce[xviii]:

Adultery

Two years desertion

Respondent undergoing a sentence of imprisonment for seven years or more for n offence

under IPC, 1860

Cruelty

Venereal diseases in a communicable form

Leprosy

Incurable insanity or continuous or intermittent mental disorder, and

Presumption of death

Further two specific grounds have been provided for the wife alone.8 They are:

The husband, since the solemnization of marriage has been guilty of rape, sodomy or

bestiality, and

Cohabitation has not been resumed for one year or more after an order of maintenance

has been passed under section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code.

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground of Divorce

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a separate ground of divorce has not yet found a place in

the marriage statutes in India, viz., the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, the Special Marriage Act 1954,

the Divorce Act, 1869 (2001) the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936, the Dissolution of

Muslim Marriage Act 1939. The foundation of a sound marriage is tolerance, adjustment and

respect for one another. Tolerance to each other‟s fault to a certain bearable extent has to be

inherent in every marriage. Petty quibbles and trifling differences should not be exaggerated and

magnified to destroy what is said to have been made in heaven. All quarrels must be weighed

from that point of view in determining what constitutes irretrievable breakdown of marriage in

each particular case and always keeping in view the physical and mental conditions of the

parties, their character and social status. A too technical and hypersensitive approach would be

8

As under S. 27(1A) of the Act

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 14

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

counter-productive to the institution of marriage. The Courts do not have to deal with ideal

husbands and ideal wives. They have to deal with a particular man and woman before them.

In Harendra Nath Burman v. Suparva Burman,9 the Court observed that the mere breakdown of

marriage, however irretrievable, is not by itself and without more, any ground for dissolution of

the marriage as yet under our matrimonial law. However, in Ram Kali v. Gopal, 10 the Court

observed, “it would not be practical and realistic, indeed it would be unrealistic and inhuman, to

compel the parties to keep up the façade of marriage even though the essence of marriage

between them has completely disappeared and there are no prospects of their living together as

husband and wife”.

Desertion

Section 27(1) of the SMA, 1954 deals with „desertion as a ground for divorce‟. The section

requires a period of atleast two years desertion as a pre-condition to a decree for divorce.

DEFINITION

Desertion means “the wilful and unjustified abandonment of a person‟s duties or obligation

especially to….a spouse or family”[xxv], or in simpler words it is the rejection of, either party to

a marriage, all the obligations that arise from the wed-lock. The explanation to clause (1) of S. 27

of the SMA gives the following definition,

“Desertion of the petitioner by the other party to the marriage without any reasonable cause and

without the consent or against the wishes of such party, and includes wilful neglect of the

petitioner by the other party to the marriage, and its grammatical variations and cognate

expressions.”

Thus desertion is an unreasonable withdrawal from the company of the spouse and of the exiting

state of affairs. In simple English it can also be termed as “abandonment”.

Desertion can basically be of the following types:

Actual desertion

Constructive desertion

9

AIR 1989 Cal 120

10

AIR 1971 Del 6 (FB).

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 15

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Wilful neglect

The concept of restitution of conjugal rights has its roots in the fact that at time of marriage, the

parties to the marriage have a right to enjoy each other‟s consortium or company. In other words,

it is a duty to cohabit.

Like many other remedies, the origin of this remedy goes back to feudal England, where

marriage was considered as a property deal and the wife was seen as part of the man‟s possession

like all other chattel. It was this very same idea that was introduced into the British colonies

including India. In India, a decree for the restitution of conjugal rights can still be executed by

attachment of the respondent‟s property[lxxi].

Section 22 of the SMA, 1954 covers the ground of restitution of conjugal rights. The provision in

the SMA has been worded similar to Section 9 of the Hindu Marriage Act and runs as follows:

“when either the husband or the wife has without reasonable excuse, withdrawn from the society

of the other, the aggrieved party may apply, by petition to the District Court, for the restitution of

conjugal rights and the court on being satisfied of the truth of the statements made in such

petition and that there is no legal ground why the application should not be granted, may decree

restitution of conjugal rights accordingly.”

The explanation to this section further provides that,

“where a question arises, whether there has been reasonable cause for withdrawal from the

society, the burden of proving reasonable excuse shall be on the person who has withdrawn from

the society.”[lxxii]

It can thus be summarised that the following are necessary for a decree for the restitution of

conjugal rights:

That the respondent has withdrawn from the society of the petitioner

That the withdrawal is without reasonable excuse or cause

That the court is satisfied about the truth of the statement made in such petition, and

That there is no legal ground why relief should not be granted

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 16

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Conclusion

Hence, the above discussed general and legal aspects of Special Marriage Act, holds high

importance not only for the people who have registered their marriage under the act but also to

all the citizens of the country in order to have a better understanding of the law and treat the

marriages between different castes and religions to be equally sacred and auspicious like the

marriages between one‟s own caste. With my article I assume to have made my point on Special

Marriage Act which every Indian should know, and once they know, the country will surely

become a better place to live with the crimes of honor killing and torture etc. to come to an end.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 17

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Parsi Marriage Act

Introduction

The Parsis immigrated to India nearly 1200 years ago when Persia was overrun by the followers

ofthe Islam. Instead of dying by the sword and surrendering their religion to that of conquers the

followers of Zoroaster preferred to migrate to this country. When they arrived in India in 717

A.D., they entered into an agreement with the Hindu ruler of Sanjan. By the agreement, they

initially settled to respect the cow and observe many customs of the Hindus. With preserving

their own religion, they adopted the prevailing customs of local population.11

The term 'Parsi' is defined in its Section 2(7) as Parsi Zoroastrian who professes the Zoroastrian

religion. A Zoroastriarr, however, need not necessarily be a Parsi. . The word 'Parsi' has only a

racial significance and has nothing to do with his religious profession. The word 'Parsi' is derived

from ' Pers' or 'Fairs' a province in Persia from where the original Persians migrated to India and

came to he known as Parsis.12

Concept of Marriage Among Parsis Before 1865 –

From their arrival in India up to 1865 the Parsis had no recognized laws to govern their social

relations. When they settled in Western India they probably brought with them a system, both

law and custom, from Persia. But it was unwritten and fell into desuetude, and naturally adopted

much ofthe law and usage that obtained in the Hindu community inter alia, as to marriage.13

Changes Brought in the Attitude Towards Parsi Marriage by the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act,

1865 –

The Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1865 for the first time, had made certainty in the

matrimonial law of the Parsis. The Act of 1865 made polygamous marriage as invalid and

imposed a punishment also. The divorce was also introduced and the concept ofindissolubility

ofthe marriage came to an end. The Act made other changes also –

The Act, 1865 had made sufficient provisions by which polygamous marriage could be

restricted. Section 9 ofthe Act, 1865 had imposed the punishment extendable six months

11

Nooroji v. Kharshedji, I.L.R. 13 Bom. 21.

12

See, Sir Dinshaw v. Sir Jamshedji, 11 Bom. LR 85

13

Peshotam v. Meherbai, 13 Bom. 307.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 18

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

or penalty extendable to two hundreds rupees or both against a priest who knowingly or

willfully solemnized any marriage contrary to and in violation of section 4 (polygamous

marriages). The penalty was also imposed against attesting witness which had given a

false statement as forgery defined in India Penal Code, 1860 and was also made liable for

conviction under section 466 ofthe said code."14

The section 4 of the Act, 1865 had abolished the custom of polygamous marriage

prevailing before this Act and declared such marriage as void. Formally, second

marriages among Parsis had been numerous. Without any former precedent ofthe rigid

enforcement of the penalties of the law, such second marriage had been frequent down to

the date on which Act XV of 1865 came into operation.15

The Act, 1865 made compulsory for officiating priest to issue certificate of marriage

immediately after the solemnization of marriage. The certificate was required to be

signed by the said priest, the contracting parties or their father or guardian when they

were not completed the age of 21 years and two witnesses present at the time of the

marriage. A duty was also imposed by the same section that officiate priest had to sent

the certificate along with a fee of two rupees to be paid by husband, to the

concerned'Registrar who shall had register the marriage and made entries

accordingly.The Act, 1865 made the registration of Parsi marriage as compulsory.

Section 10 ofthe Act, 1865 had made provision that if any priest neglecting to comply

with any ofthe requisitions affecting him contained in the aforesaid section (section 6)

was punished for a period extendable to three months or with a fine extendable to one

hundred rupees or both. Section 13 of the Act, 1865 had also made liable for conviction if

he was failed to register the marriage in pursuance of certificate of priest.

Before this Act came into operation, a Parsi contracting a second marriage in the lifetime

of his or her wife or husband could not be punished under Indian Penal Code, I860. 16 The

section 5 ofthis Act laid down the specific provision and the husband or wife ofsecond

marriage was made liable to penalties under sections 494 and 495 ofthe Indian Penal

Code, 1860.

14

Section 12 ofthe Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1865.

15

Merwanji v. Avabai, 2 Bom. 231.

16

Avabai v. Jamasji, 3 B.H.C. 113 at 115.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 19

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Requirements of a Parsi Marriage –

The Act of 1865 had laid down essential requisite for validity of a Parsi marriage. Section 3

ofthe Act specified –

(1) The marriage should not be contracted within the prohibited degree of consanguinity and

affinity,

(2) it must be celebrated according to the ceremony called 'Ashirvad'; (3) the ceremony must

be performed by Parsi priest;

(4) the ceremony must be performed in the presence of two "Parsis witness'; and

(5) in case of either party being under twenty one, the consent of his or her father or guardian

must be previously obtained. A list ofthe persons of prohibited degree had been published in

Gazette of India17

According to the list, a man was prohibited not to marry with his thirty-three relations and

woman was also prohibited not to marry with her thirty-three relations. The prohibition was

made on the ground of consanguinity and affinity.

The observance of 'Ashirvad' ceremony was also made compulsory. The ceremony has been

explained by Dosabhai Framji Karaka in his History of the Parsis18

One of the essential requisite for a valid marriage according to section 3 of the Act, 1865 was

the consent of guardian or father must be obtained in case where either party was under

twenty one years of age at the time of marriage. Section 3 of the Indian Majority Act, 1875

provides the age of majority at eighteen years, but section 2, clause (c) ofthe Act, 1875

provides that the Act shall not affect the capacity of any person to act in matter of marriage,

dower, divorce and adoption. Therefore, the Court held that for Parsi marriage the age of

majority would be 21 year and provision ofIndian Majority Act, 1875 would not apply.19

Nullity of Marriage –

The Act, 1865, provided provisions for nullity of marriage. The grounds were specified three

in numbers. They were lunacy or habitually unsoundness mind of the either party to the

marriage,20 or non consummation of marriage due to natural cause. Here, the Act, 1865 also

required that the petitioner had to established that the respondent was lunatic or of unsound

17

Gazette ofIndia, 9th September, 1865, at 981, 982.

18

Dosabhai Framji Karaka, 1884, History of the Parsis, Vol. I, at 178

19

Bai Shirin bai v. Kharshedji, 22 Bom. 430.

20

Section 27 ofthe Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1865.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 20

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

mind at the time of marriage and still continued up to passing of decree. Similarly, he had,

also, to establish that the consummation of marriage became impossible due to impotency of

the respondent by reason of natural cause. If the petition was aware of the fact of lunacy or

unsoundness of the respondent at the time of the marriage, he was declared not to get a

decree of nullity on such grounds in the Act. The Act, 1865 imposed a strict burden of proof

on the petitioner in case of impotency. Here, he had to prove an absolute impotency of the

respondent was the cause for not consummation of marriage and in future it was impossible

to consummate the marriage due to such impotency.

Dissolution ofMarriage

The marriage under the Act, 1865 was dissolved when husband or wife had been

continuously absent and was not heard by those persons who would naturally have heard of

him or her had he or she been alive.21 On this ground also, the marriage might be dissolved at

the instance of either party thereto and not by the third party. Section 30 of the Act, 1865 also

provided for dissolution of the Parsi marriage on fault grounds as obtain under English Law.

Sorabji v. Buchoobai22 - The court had expressed the view on the point of age ofparties in

respect to filling of the suit that for the purposes of this Act, age of majority would be 21

years and not 18 years. The consent of guardian was required if any parties had been minor.

21

Section 29 ofthe Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1865.

22

18 Bom. 366

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 21

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

DIVORCE

Section32 of the Act provides the following grounds for divorce –

(a) that the marriage has not been consummated within one year after its

solemnization owing to the willful refusal of the defendant to consummate it;

(b) that the defendant at the time of the marriage was of unsound mind and has been

habitually so up to the date of the suit: Provided that divorce shall not be granted

on this ground, unless the plaintiff

(1) was ignorant of the fact at the time of the marriage, and

(2) has filed the suit within three years form the date of the marriage;

(bb) that the defendant has been incurably of unsound mind for a -period of two years

or upwards immediately preceding the filing of the suit or has been suffering

continuously or intermittently from mental disorder of such kind and to such an

extent that the plaintiff cannot reasonably be expected to live with the defendant.

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a ground of Divorce

Irretrievable breakdown of marriage as a separate ground of divorce has not yet found a place in

the marriage statutes in India, viz., the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, the Special Marriage Act 1954,

the Divorce Act, 1869 (2001) the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936, the Dissolution of

Muslim Marriage Act 1939. The foundation of a sound marriage is tolerance, adjustment and

respect for one another. Tolerance to each other‟s fault to a certain bearable extent has to be

inherent in every marriage. Petty quibbles and trifling differences should not be exaggerated and

magnified to destroy what is said to have been made in heaven. All quarrels must be weighed

from that point of view in determining what constitutes irretrievable breakdown of marriage in

each particular case and always keeping in view the physical and mental conditions of the

parties, their character and social status. A too technical and hypersensitive approach would be

counter-productive to the institution of marriage. The Courts do not have to deal with ideal

husbands and ideal wives. They have to deal with a particular man and woman before them.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 22

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Where the parties were living separately for sixteen years without any chance of reconciliation,

the Court held that marriage had broken down and dissolution of marriage was justified.23 It may

be noted that in this case the term “irretrievable breakdown” has not been used; only “broken

down” has been stated. But lately even the Apex Court is using the phrase “irretrievable

breakdown of marriage”.24 In Gajendra v. Madhu Mati,25 it was held that where parties have

been living separately for seventeen years, the chance of their re-union may be ruled out and it

may be reasonable to assume that the marriage has broken down irretrievably. So the marriage

should be dissolved.

Divorce by Mutual Consent

As per the provisions of Section 32-13 of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act a suit for divorce

by mutual consent may toe filed by both the parties to a marriage together, whether such

marriage was solemnised before or after the commencement of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce

(Amendment), Act, 1939. Section 32--B of the Act makes it abundantly clear that its provision

will have a retrospective effect. Divorce by mutual consent can therefore be sought by a Parsi

couple irrespective of when their marriage was solemnized i.e. before or after the

commencement of the amending Act of 1938.26

The requirements of seeking divorce by mutual consent are –

1. Both spouses should together present a suit for divorce

2. The spouses should have been living separately for a period of one year or more

3. The spouses could not adjust with each other and had not been able to live

together

When the decree for divorce by mutual consent is passed, the marriage-tie gets

dissolved from the date of decree and not with effect from the date of the presentation

of petition27

23

Krishna Banerjee v. Bhanu Bikash Bandyopadhyay AIR 2001 Cal 154 (DB).

24

Jordan Diengdeh v. S.S.Chopra AIR 1985 SC 925

25

II (2001) DMC 123 (MP)

26

M. Shabbir and Manchanda, Parsi Law in India, p. 62 (1991).

27

Ravi Shankar v. Sharda,, AIR 1978 MP p.44.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 23

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Judicial Separation –

The main improvements introduced by the .1936 Act were that it put husband and wife on an

equal footing so far as judicial separation was concerned, made judicial separation obtainable on

all grounds of divorce alognwith cruelty and declared failure to comply with a restitution decree

to be a ground for divorce,, It is also provided that a Parsi would be prohibited from remarrying

even if he or she changed his or her religion or domicile unless his or her previous marriage was

dissolved under the Act. If a Parsi, in violation of Section 4(1), marries again in the life-time of

his or her wife or husband before the dissolution of earlier marriage by a competent court hce or

she is punishable under criminal law28

Section 4 of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act 1936, therefore classifies even genuine converts

to Islam into two classes - (1) converts from Parsi Community and (2) converts from other

communities and discri.minaxt.es against the former by depriving them of the right to plurality of

wives permitted under the Muslim Law As as ready noted , the discriminationis absolutely based

on ethinicity and race and is thus violative of Article 15. The Parsis have accordingly been

denied Equality before the Law and Equal protection of the Laws in violation of Article .14 also.

This has again been reiterated with clearer assertion in Section 52(2) providing that once a Parsi

has married under this Act, or the preceding Act of 1865, he "shall remain bound by this Act,"

"even though such Parsi may change his or her religion," until such marriage terminates in due

course.

Section 34 of the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, enables either par ty to t he mar r i ag e

to sue for 'Judicial Separation' on any of the grounds for which a party could have filed a suit for

divorce; or , any of the grounds that the defendant has been guilty of such cruelty to him or her

or their children 5 or, has used such violence, or has behaved in such a way as to render it, in the

judgment of the court, improper to compel him or her to remain with the defendant.

28

8. V. B. ILR 16 Bom. 639.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 24

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

Indian Divorce Act

Under all the Indian Personal laws, dissolution of marriage is based on guilt or fault theory of

divorce. It is only under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, the Special Marriage Act, 1954 and the

Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936 that divorce by mutual consent and on the basis of

irretrievable breakdown of marriage are also recognized. Further, under Muslim law, the

husband as the right to unilateral divorce. In order, to make the law more equitable the

Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939 provides a woman married under Muslim law with

the option of seeking divorce on certain fault grounds.

As the field of Personal Law is a vast field so I have restricted the scope of this research paper to

the fault ground theory of divorce under Indian personal law. The research paper analyzes the

common aspects between the provisions of the various personal law statutes and further look at

the legal implications of these.

Also there are elements of difference between the various statutes, keeping in mind the

feasibility of trying to resolve such differences in order to come up with a single, comprehensive

law, at least as regards divorce.

The Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936 recognizes the principle of equality and lays down

grounds for divorce which either spouse can avail of, for example, it recognizes unnatural

offences as a ground for divorce for either spouse, unlike the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 and the

Special Marriage Act, 1954.

It is only the Indian Divorce Act, 1869 that discriminates against the wife.

Hindu law gives the following four grounds for the wife alone -

That the husband has another wife from before the commencement of the Act, alive at the time

of the solemnization of the marriage of the petitioner. For example, the case of Venkatame v.

Patil , where a man had two wives one of whom sued for divorce, and while the petition was

pending, he divorced the second wife. He then averred that since he was left only with one wife,

and the petition should be dismissed. The Court rejected the plea.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 25

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

That the husband has, since the solemnization of the marriage, been guilty of rape, sodomy or

bestiality

Non-resumption of cohabitation for one year after an order of maintenance

That the marriage was solemnized before she attained the age of fifteen years, and she has

repudiated the marriage after attaining that age, but before the age of eighteen.

Now, the Special Marriage Act, 1954, provides only two grounds of divorce to the wife, namely,

rape, sodomy or bestiality and the on-resumption of cohabitation after an order of maintenance.

Muslim law provides nine-fault founds to the wife alone, seeing that the husband has the

provision of unilateral divorce in his favor. These grounds, briefly put, are -

Whereabouts of the husband not known for four years

Neglect or failure of the husband to pay maintenance for a period of two years

Sentence to a seven year imprisonment for the husband

Failure to perform marital obligations by the husband for a period of three years

Impotency of the husband at the time of marriage and after

Insanity of husband for a period of two years or that he is suffering from leprosy or a virulent

venereal disease

That the marriage was solemnized before she attained the age of fifteen years, and she has

repudiated the marriage after attaining that age, but before the age of eighteen.

On the grounds of cruelty – The concept of cruelty is clearly spelt out, and has been described

earlier in the project

Any other ground recognized as valid under Muslim law.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 26

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

CONCLUSION

A single codified law does not define the personal law, in India. We have the Hindu, Muslim,

Christian, Jewish and Parsi laws. There are various matrimonial statutes laying down the

provisions for each of these laws. Even the institution of divorce has different implications under

these laws. While it is only under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, the Special Marriage Act, 1954

and the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936 that divorce by mutual consent and on the basis of

irretrievable breakdown of marriage are also recognized, Muslim law provides the husband with

the right of unilateral divorce, while the wife can only rely on certain prescribed fault grounds.

Fault grounds as the basis for divorce are given in all the Indian matrimonial statutes. The

researcher has focused on these fault grounds in this project.

I realized that there are a number of provisions that quite similar between the various statues and

the kinds of problems that arise before courts, when it comes to implementation of such rules.

I looked at the elements of difference between the various statutes, looking at the differences that

used to exist in the personal laws earlier and how some changes are being brought, through

amendments to reconcile them with the changing socio-religious circumstances.

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 27

Special Marriage Act and The Parsi Law of Marriage

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Modern Hindu Law, Paras Diwan, 43rh Edition

Academia.edu

Wikipedia.org

Scribd.com

Indiankanoon.com

Scconline.com

Manupatra.com

Faculty of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia Page 28

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Prueba Diagnóstico Inglés 8 BasicoDokument4 SeitenPrueba Diagnóstico Inglés 8 BasicoDenisse Payacan Pizarro100% (2)

- Law of Evidence AssignmentDokument27 SeitenLaw of Evidence AssignmentSandeep Chawda33% (6)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Structural Family TherapyDokument30 SeitenStructural Family TherapyEvan Gi Line100% (3)

- JurisprudenceDokument16 SeitenJurisprudenceSandeep Chawda100% (1)

- Script Coco TrailerDokument3 SeitenScript Coco Trailerapi-591320437Noch keine Bewertungen

- George Eliot's "The Mill on the FlossDokument7 SeitenGeorge Eliot's "The Mill on the FlossGirlhappy RomyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sexuality in The Czech New WaveDokument9 SeitenSexuality in The Czech New WaveJanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Insurance Karwalo ApnaDokument10 SeitenInsurance Karwalo ApnaSandeep ChawdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cs Flaw LLB Sem10Dokument17 SeitenCs Flaw LLB Sem10faarehaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Assignment On Legal PersonalityDokument15 SeitenJamia Millia Islamia: Assignment On Legal PersonalitySandeep ChawdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- C C C VDokument9 SeitenC C C VCAJayeshparakhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law and ITDokument25 SeitenLaw and ITSandeep ChawdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difference Between Summon and WarrantDokument13 SeitenDifference Between Summon and WarrantSandeep Chawda100% (1)

- Ipr Sandeep VinayDokument22 SeitenIpr Sandeep VinaySandeep ChawdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alternate Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in IndiaDokument84 SeitenAlternate Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in IndiaSandeep Chawda100% (1)

- C C C VDokument9 SeitenC C C VCAJayeshparakhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane Hellein - Toward A Feminist Anthropology of ChildhoodDokument12 SeitenJane Hellein - Toward A Feminist Anthropology of ChildhoodHildon CaradeNoch keine Bewertungen

- PatriarchyDokument10 SeitenPatriarchySwar DongreNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of France: by M. GuizotDokument275 SeitenHistory of France: by M. GuizotGutenberg.org100% (1)

- Approaching Sexual Potential in RelationshipDokument13 SeitenApproaching Sexual Potential in RelationshipAna AchimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bicos Injetores ComparaçãoDokument2 SeitenBicos Injetores ComparaçãoJose MarcosNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSFAS Appeals Process PDFDokument11 SeitenNSFAS Appeals Process PDFYandiswa NdabenhleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jane AustenDokument25 SeitenJane Austenalex1971Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mens OpenDokument36 SeitenMens OpenJason MartinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diwali PDFDokument2 SeitenDiwali PDFYogesh PatilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asl Class 9 - StudentsDokument3 SeitenAsl Class 9 - StudentsMeenakshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Perspectives Mock ExamDokument7 SeitenGlobal Perspectives Mock ExamvtejonNoch keine Bewertungen

- SSS Law ReviewerDokument7 SeitenSSS Law ReviewerKL NavNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Feminist Critique of Family StudiesDokument12 SeitenA Feminist Critique of Family StudiesConall CashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formal Writing 1Dokument7 SeitenFormal Writing 1api-301937254Noch keine Bewertungen

- Úvod Do Anglického JazykaDokument24 SeitenÚvod Do Anglického JazykaTomas CsomorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matrimonialndu Marriage Act2Dokument21 SeitenMatrimonialndu Marriage Act2altmashNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 Step Recovery Groups 1 2Dokument1 Seite12 Step Recovery Groups 1 2kuti kodiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bach Fugue No. 9 in E majorDokument3 SeitenBach Fugue No. 9 in E majorHenry Sloan100% (1)

- Ten CommandmentsDokument38 SeitenTen CommandmentsfatherklineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocabulary: Complete The Chart With The Words BelowDokument2 SeitenVocabulary: Complete The Chart With The Words BelowbabetesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Separation To Property RegimesDokument23 SeitenLegal Separation To Property RegimesCars CarandangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chicka Chicka Boom BoomDokument53 SeitenChicka Chicka Boom BoomMarkeeta Gillenwater100% (5)

- Effects of PardonDokument2 SeitenEffects of Pardonkhayis_belsNoch keine Bewertungen

- 13Dokument3 Seiten13NympsandCo PageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Kunjungan Pasien 2022Dokument179 SeitenData Kunjungan Pasien 2022selvi alisyasNoch keine Bewertungen