Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

3

Hochgeladen von

sabirbdkOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

3

Hochgeladen von

sabirbdkCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

International Journal of Consumer Studies ISSN 1470-6423

‘Hello, Mrs. Sarah Jones! We recommend this product!’

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising:

comparisons across advertisements delivered via three

different types of media ijcs_784 503..514

Jay (Hyunjae) Yu1 and Brenda Cude2

1

Manship School of Mass Communication, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

2

College of Family and Consumer Sciences, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

Keywords Abstract

Personalized advertising, privacy, advertising

effect, consumer behaviour. As new technologies (e.g. online, mobile and interactive TV) develop worldwide, numer-

ous types of personalized advertising, in which companies use an individual’s name and/or

Correspondence other types of personal information, have become more popular in many countries. Using

Jay (Hyunjae) Yu, Manship School of Mass many types of information about specific individuals, personalized advertising is designed

Communication, Louisiana State University, to convey a customized message at the right time to the right person using diverse media.

Baton Rouge, LA 70808, USA. However, despite its universally increased use, few academic studies have explored the

E-mail: Bus89@lsu.edu effectiveness of personalized advertising and consumers’ response to it. This exploratory

study focused on consumers’ perceptions of personalized advertising delivered online

doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2009.00784.x (e-mail) and offline (letter and telephone call). The results show that consumers generally

have negative perceptions of personalized advertising, regardless of how it is delivered,

with the strongest negative reaction to telephone calls.

Companies’ interest in planning and conducting personalized possible (Pramataris et al., 2001; Howard and Kerin, 2004;

advertising is increasing around the world (Poon and Jevons, Morimoto and Chang, 2006). not just to developed western coun-

1997; Gal-Or and Gal-Or, 2005). Researchers from diverse coun- tries, but worldwide (Consumers International, 2002). Personal-

tries including the US, China, South Korea, Greece, Mexico, ized advertising can be delivered using techniques more advanced

Taiwan, Poland and Germany have recently investigated several than traditional e-mails, including personalized web pages that use

issues regarding this miraculous boom in personalized advertising cookies to capture an individual’s history of web surfing, person-

(Bozios et al., 2001; Yuan and Tsao, 2003; Chorianopoulos et al., alized interactive television advertising, smart banners and mobile

2004; Tsang et al., 2004; Bulander et al., 2005; Kazienko and advertising (Bozios et al., 2001; Pramataris et al., 2001; Yuan and

Adamski, 2007). One of the major motivations for this universal Tsao, 2003).

interest in personalized advertising is directly related to marketers’ The Internet’s popularity in daily life in many countries around

increasing doubts about the effectiveness of many traditional the world has also given companies another way to gather con-

advertising methods that target mass audiences, methods they have sumer information for marketing purposes (M2PressWIRE, 2006;

long relied upon to market a variety of products (Jin and Villegas, Trollinger, 2006). Companies use all possible channels, both

2007). The effectiveness of traditional mass advertising, which is online and offline, to develop personal information databases

generally produced in identical messages for a non-specific audi- about consumers (Marketing News, 2006). These databases make

ence, has been questioned due to diverse reasons, such as increas- it possible to create personalized advertisments with customized

ing advertising clutter (Rotfeld, 2006), people’s general avoidance messages for each individual consumer (Kim et al., 2001; Yuan

of advertising (Kim and Pasadeos, 2007), and the development and Tsao, 2003; Lekakos and Giaglis, 2004; Wolin and Korga-

of several technologies such as DVRs (Digital Video Recorders) onkar, 2005).

that allow consumers to avoid exposure to advertisements if they However, despite the increase in the amount of personalized

choose (‘Digital Home Technology: Tivo Builds Real Time DVR advertising, as well as the development of diverse new technolo-

Advertising Research Offering’, 2006). gies that can be used to deliver it, few academic researchers have

The development of new communication technologies may not examined consumer responses to it (Sundar and Kim, 2005).

only have weakened traditional advertising’s effectiveness, but it Researchers from many countries (e.g. Li et al., 2002; Sheehan

also has made delivery of diverse types of personalized advertising and Hoy, 1999; Wu, 2006) have noted the need to learn more about

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 503

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

consumers’ attitudes towards the phenomenon known as person-

alized advertising. While a personalized advertising message may

The increasing prevalence of

be more effective because the message is individualized (Pavlou

personalized advertising

and Stewart, 2000), it also may be rejected by consumers who are Given the popularity of one-to-one marketing (Friedman and

concerned about their privacy (Sheehan and Hoy, 1999; Miyazaki Vincent, 2005), database marketing (Wehmeyer, 2005) and rela-

and Fernandez, 2000; Sacirbey, 2000; Phelps et al., 2001). This tionship marketing (Palmatier et al., 2006), companies’ interest

could possibly lead to negative attitudes as well as the marketer in collecting consumers’ personal information is greater than

(Sheehan and Gleason, 2001). ever worldwide. In the US, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

Motivated by the controversy surrounding the effects of per- reported that approximately 92% of websites collected personal

sonalized advertising, this exploratory study investigated con- information for future marketing (FTC, 2000). Some specialized

sumers’ actual attitudes towards personalized advertising. More third parties collect and sell information to other companies as

specifically, this study aimed to learn if consumers’ perceptions well (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000). Basic database programs can be

of personalized advertising differ depending on the type of merged to provide an in-depth portrait of a consumer’s individual

media used to deliver it: online (e-mail), offline mail (letter), and purchasing behaviour (Foxman and Kilcoyne, 1993), including

telephone (solicitation phone call). In addition, this study exam- personalized information that can be diverse and include demo-

ined consumers’ self-reported responses upon receiving person- graphic characteristics, geographic information and psycho-

alized advertising, their privacy concerns and their intentions to graphic information (Lekakos and Giaglis, 2004). The FTC (2009)

purchase the product in the personalized advertisement. Finally, reported that information for personalized advertising comes from

this research investigated the relationships between consumers’ multiple sources, such as consumers’ online activities including

intentions to purchase the advertised product and three indepen- the searches they routinely conduct, the web pages they visit, and

dent variables (i.e. general perceptions of personalized advertis- even the specific content they view.

ing, actual responses to personalized advertising and privacy Personalized advertising’s popularity even challenges the long-

concerns). The influence of these three variables on consumers’ standing definition of advertising. According to the American

purchase intentions was examined for each of the three media Marketing Association (Alexander, 1960) and several researchers

types. (Rosenberg, 1995; Perreault and McCarthy, 1999; Armstrong and

Even though the sample for this study only included American Kotler, 2000), advertising is defined as any paid form of non-

consumers, the researchers expect that the results will provide personal presentation and promotion of ideas, goods or services

important implications for marketers and researchers in other by an identified sponsor through mass communication media. As

countries. In a global economy, consumers in diverse cultures have some important elements surrounding the definition change, there

much in common in terms of exposure to advertising, especially is room for re-thinking the concept of ‘non-personal’. New tech-

advertising delivered online, and thus share some common atti- nology that transforms mass communication into a series of per-

tudes about advertising (e.g. Wolburg and Kim, 1998; Adler et al., sonalized advertising messages may eventually shift the focus of

2004; Yu et al., 2008). traditional mass advertising to more individualized and focused

audiences (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000).

This study’s definition of personalized

advertising Perspective 1: positive effects of

personalized advertising

In this study, personalized advertising was defined as advertising

that is created for an individual using information about the indi- Positive aspects of personalized advertising for both consumers

vidual (Yuan and Tsao, 2003; Wolin and Korgaonkar, 2005). This and marketers have been repeatedly noted. Several researchers

information includes either personally identifying information have indicated that personalized advertising can increase user

such as one’s e-mail address, name, or residence, and/or personal involvement and thus the advertisement’s effectiveness (Stewart

information such as shopping history, websites visited, preference and Ward, 1994; Roehm and Haugtvedt, 1999; Pavlou and

for a specific product, or one’s hobby. Further, personalized adver- Stewart, 2000; Yuan and Tsao, 2003; O’Leary et al., 2004). In

tising in this study was limited to advertising delivered without the personalized advertising, consumers receive only messages that

individual’s prior permission (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000). are relevant to them, which are more likely to generate purchase

Other terms have been commonly used to mean something intentions or other desired responses (Pavlou and Stewart, 2000).

similar to personalized advertising, such as ‘customized advertis- McKeen et al. (1994) suggested that consumers’ greater involve-

ing’ (Tsang et al., 2004; Gal-Or and Gal-Or, 2005) and ‘interac- ment in advertising also increases their satisfaction with advertis-

tive advertising’ (Sasser et al., 2007). However, personalized ing. Howard and Kerin (2004) also found that personalization in

advertising is a broader term that is relevant to advertising deliv- the advertising copy increased advertising effectiveness. In their

ered via any type of media, and thus was more appropriate for experiments, the response rate to advertisements with personalized

this study.1 notes such as ‘Hello Miss OOO! Try this. It works!’ was higher

than the response rate to non-personalized advertising messages.

An important benefit of personalized advertising is the potential

1

The terms interactive advertising and customized advertising have been for increased interaction between the consumer and the adver-

mainly used in online advertising and mobile advertising contexts because tising. Nowak et al. (1999) found in their empirical study that

of their technological interactivity (Pramataris et al., 2001; Xu et al., personalized online advertising increased the possibility of

2008). clicking behaviour among consumers. Rodgers and Thorson

504 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

H.J. Yu and B. Cude Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising

(2000) also noted that referring to users by name and mentioning sive content in advertising (e.g. sex, violence) (Nathanson, 1999),

consumers’ specific interests in an advertisement can increase the sensitive nature of some products advertised (e.g. cigarettes,

interaction. Pavlou and Stewart (2000) hypothesized that the alcohol, medications) (Sheehan, 2005; Yu et al., 2008), and fraud

degree to which advertising is perceived to be personalized and in advertising (e.g. messages in diet advertising) (Moschis and

individually focused would be an important measure of advertis- Moore, 1979).

ing’s effectiveness. In 2008, the FTC proposed guidelines for advertisers regarding

personalized advertising (FTC Staff Report 2009). The FTC, as

well as regulators in several other countries (Gao, 2005), has relied

Perspective 2: negative effects of upon self-regulation rather than establishing strict regulations

personalized advertising (Bulander et al., 2005). Even countries with more restrictive tra-

While personalized advertising has benefits for both marketers and ditions in advertising regulations, such as China, Taiwan and

consumers, several scholars have noted its negative effects and South Korea (Tsang et al., 2004; Gao, 2005), have adopted a

speculated about whether the negatives might offset the positives self-regulation approach to personalized advertising.

(Sheehan, 1999; Sacirbey, 2000; Phelps et al., 2001). Tsang et al. Thus, understanding consumers’ perceptions of personalized

(2004) found that consumers who responded to their survey gen- advertising is important. Self-regulation increases the opportuni-

erally had negative attitudes towards personalized mobile adver- ties for marketers to make mistakes in preparing and delivering

tising unless they had specifically consented to it. Also, they personalized advertising, mistakes that can harm consumers.

confirmed a direct relationship between unfavourable consumer

attitudes and future consumer behaviour and suggested that it is Research questions

unwise to send personalized advertising messages to potential

customers without prior permission. This study investigated consumers’ perceptions of and attitudes

Further, many have discussed whether personalized advertising towards the three types of personalized advertising. Data were

violates consumers’ privacy rights (Sheehan and Hoy, 1999; collected via a four-part online survey. The survey addressed (1)

Miyazaki and Fernandez, 2000). In their study of online person- general perceptions of personalized advertising, (2) self-reported

alized advertising, Sheehan and Hoy (1999) found that many par- responses upon receipt of personalized advertising, (3) opinions

ticipants did not respond to personalized advertisements; in fact, about personal privacy regarding personalized advertising, and (4)

many asked their Internet Service Providers to remove them from intentions to purchase the advertised product. The results from the

the mailing list. The respondents also reported that they were less four parts indicated above were compared among the three differ-

likely to register for websites that requested their personal infor- ent types of personalized advertising (through e-mails, letters and

mation. According to the recent UPI-Zogby International Poll telephone calls).

(2007), more than 90% of the participants from diverse countries Reflecting the personalization vs. privacy debate, this study set

were concerned about their privacy or the possibility of identity out to answer the following research questions (RQ):

theft in their daily lives. Under this situation, personalized adver- • RQ 1:

tising becomes less effective for consumers everywhere if they What are consumers’ general perceptions of personalized adver-

view it as a serious invasion of their privacy (Sheehan, 1999; tising? Are their perceptions positive, negative or neutral?

Gurau et al., 2003). • RQ 2:

The dilemma of ‘personalization vs. privacy’ epitomizes this How do consumers respond when they receive personalized

complicated situation regarding the effects of personalized adver- advertising?

tising (Long et al., 1999; Caudill and Murphy, 2000; Mabley, • RQ 3:

2000). As online users become more sophisticated and advertisers What are consumers’ perceptions of the effect of personalized

create more ways to deliver targeted content, both consumers and advertising on their privacy?

marketers expect personalized advertising more than ever. Gurau • RQ 4:

et al. (2003) reported that many customers want more individu- How does personalized advertising affect consumers’ intentions

alized attention, one-to-one communication and personalized to purchase the advertised product?

offers. On the other hand, the potential for abuse to individual The next research question examined possible differences

consumers has increased exponentially as the amount of personal between the media used to deliver personalized advertising.

data collected in consumer marketing database has grown Chaudhuri and Buck (1995) indicated that media differences are

(Caudill and Murphy, 2000). Therefore, several researchers have one of the key determinants of consumers’ emotional and rational

warned marketers not to use personalized advertising without responses to advertising. According to their study, media differ-

questioning its possible negative effects (e.g. Nowak et al., 1999; ences were the best predictor of consumers’ responses to adver-

Sacirbey, 2000). tising. Several other researchers also have documented the

The possibility of violating consumers’ privacy has lead to new relationship between media type and attitudes towards advertising

discussions about regulations for diverse types of personalized (e.g. Krugman, 1965; Petty and Cacioppo, 1986; Cutler and

advertising in many countries including the US, China and several Thomas, 2000; Chachko, 2004). More specifically, Trollinger

European countries (Gao, 2005; King, 2008). Issues surrounding (2006) recently suggested media balance in using personalized

personalized advertising and privacy are a comparatively new advertising, suggesting that e-mail and traditional offline mail

realm because the major topics in advertising regulation have together achieve a better result than e-mail alone. He recom-

traditionally dealt with specialized audiences (e.g. children, ado- mended the combination based upon the notion that consumers

lescents senior citizens) (Ward, 1976; Pereira et al., 2005), offen- generally respond differently to the two types of media.

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 505

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

Thus, Research Question 5 asked: 5 days. In addition to receiving extra credit from their professors,

• RQ 5: the participants were entered in a drawing for a $50 gift card to the

How do the different media used to deliver personalized adver- campus bookstore.

tising affect general perceptions of personalized advertising, The questionnaire included four major sections reflecting the

self-reported response to personalized advertising, perceptions first four research questions (see Table 1–4). As indicated above,

of the interaction of personalized advertising with privacy, and the four topics have been a main focus in discussions related to

consumers’ purchase intentions? personalized (customized) advertising and one-to-one marketing:

(1) general perceptions of personalized advertising (Nowak et al.,

The next question dealt with the effect of gender differences on

1999; Pavlou and Stewart, 2000); (2) actual behaviours in

consumers’ opinions about personalized advertising through the

response to personalized advertising (Sheehan and Hoy, 1999;

three types of media. Sheehan (1999) and Wolin and Korgaonkar

Howard and Kerin, 2004); (3) consumers’ privacy concerns

(2005) have identified gender as a significant factor in the level of

regarding personalized advertising (Sacirbey, 2000; Phelps et al.,

privacy concern experienced when exposed to personalized adver-

2001); and (4) consumers’ intentions to purchase the product

tising. Thus, the sixth research question was:

advertised (Chachko, 2004; Sundar and Kim, 2005). Each section

• RQ 6:

of the survey included five specific statements asking for con-

How does gender affect general perceptions of personalized

sumers’ opinions using an agree–disagree 5-point scale, with ‘5’

advertising, self-reported response to personalized advertising,

representing agreement. In each section, the same questions were

perceptions of the interaction of personalized advertising with

asked three times about the three different media: (1) online

privacy, and consumers’ intentions to purchase the product

(e-mail), (2) offline mail (letter), and (3) offline (phone call).

advertised?

The participants were given the researchers’ definition of per-

Lastly, the possible relationships between consumers’ inten- sonalized advertising prior to taking the survey (‘Personalized

tions to purchase the advertised product and the three independ- advertising is defined as advertising that is created for an individual

ent variables (general perceptions of personalized advertising, using information about the individual, either personally identify-

self-reported responses to personalized advertising and privacy ing information such as one’s e-mail address, name, or residence,

concerns) were examined. The three variables’ influence on con- and/or personal information such as shopping history, preference of

sumers’ purchase intentions has been an important topic in con- a specific product or hobby. Also, personalized advertising in this

sumer marketing literature for a long time (e.g. Phelps et al., 2001; study is limited to advertising delivered without the individual’s

Tsang et al., 2004). Research Question 7 specifically dealt with an prior permission’). All of the items in the survey questionnaire were

implication of the relationships above in a personalized advertis- pre-tested with 30 randomly selected consumers who had charac-

ing context: teristics similar to those of the actual participants.

• RQ 7: Each set of questions regarding the three different types of

How do general perceptions about personalized advertising, media was preceded by one of the following statements to put the

self-reported responses to personalized advertising and privacy questions in context:

concerns influence consumers’ intentions to purchase the • Have you ever received an e-mail that had your name (or your

product in personalized advertising delivered via three different online name) in the title such as ‘Hello, Sarah’ or ‘Hello, Shopgirl

types of media (online, letter and telephone calls)? 501’ from advertisers you don’t know?

• Have you ever received mail (offline, letter) that had your name

(or your address) in the title such as ‘Mr. Douglas, Mrs. Jones’

Method from advertisers (company, store, brand, people) you don’t know?

• Have you ever received a phone call that indicated your name (or

Sample

your other personal information) such as, ‘Hello, Mr. Geller’ or

A total of 231 young adults (college students, between the ages of ‘Hello, Mrs. Jones’ from advertisers (people, company, brand,

19 and 24) were recruited as the participants for the survey. Young store) you don’t know?’

adults in this age range are one of the major consumer groups Participants responded to a total of 60 statements (20 per each

for diverse products not only in the US but also in many other media type). In addition, they also indicated their gender and age

countries (Huang, 1998; Sheehan, 1999; Tsang et al., 2004; Paek, as well as their e-mail address to contact them regarding compen-

2005). To recruit a convenience sample, the researchers selected sation for participation in the survey.

an introductory journalism class at a state university in the south-

eastern part of the US. With the professor’s authorization, one of

the authors visited the class and briefly explained the nature of the

Results

survey. Only the title and topic of the study were made known to

(RQ1) General perceptions regarding three

the participants. The online survey was conducted using Survey

types of personalized advertising

Monkey website (http://www.surveymonkey.com).

An author sent e-mails to all 231 students in the class to invite Overall, the consumers’ general perceptions of personalized

them to participate in the survey; the e-mail provided the link to advertising were negative (see Table 1). However, they were less

the survey questionnaire. Among the 231 participants, 195 partici- likely to take personalized advertising seriously if it was delivered

pants responded to the survey (84.4%), and all but three provided online (mean 4.1) rather than offline by mail (mean 3.6) or tele-

complete responses. Consequently, 192 completed surveys were phone (mean 3.97). All differences by media type were significant

used for the analysis. The survey was conducted over a period of in the t-tests at the P < 0.01 level. The typical response to the

506 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

H.J. Yu and B. Cude Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising

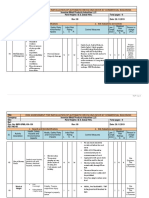

Table 1 General perceptions of personalised advertising

Gender Media

Statement Mean difference difference

When I receive personalized advertising that has my name on the title from an advertiser P < 0.01

(company, brand, people) who I don’t know, I don’t generally take it seriously.

Online mail 4.10

Offline mail 3.60

Telephone call 3.97

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I feel curious and uncomfortable because P < 0.01

the advertisers got my personal information without letting me know.

Online mail 3.92 P < 0.01 (female)

Offline mail 3.08

Telephone call 3.63

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, even though it is an unfamiliar advertiser, P < 0.01

I will be interested if it is about a product I like.

Online mail 2.06

Offline mail 3.07

Telephone call 1.84

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I feel I am being treated with special care. P < 0.01

Online mail 1.45 P < 0.05 (female)

Offline mail 2.09

Telephone call 1.63

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I am upset because my e-mail address P < 0.01

(address, telephone number) is my important personal information.

Online mail 3.68

Offline mail 3.09

Telephone call 3.79

statement, ‘When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I to a phone call even if it was personalized (mean 1.95 online mail;

feel curious and uncomfortable because the advertisers got my 3.32 offline mail; 1.81 telephone call). They were more likely to

personal information without letting me know’ was general agree- open offline mail than to open an e-mail or take a telephone call.

ment – means of 3.92 for online personalized advertising, 3.08 for Although respondents answered that they tended not to read or

offline mail, and 3.63 for a telephone call. listen to personalized advertising, they also did not complain to

The responses to a somewhat stronger reaction (‘being upset’) marketers about the advertising or seek more information about

to personalized advertising were similar with the most negative the advertised products. Respondents generally did not demand to

response being to a telephone call. The two statements that know how the advertiser got their personal information (mean 1.6

described potential benefits of personalized advertising to con- online mail; 1.62 offline mail; 2.23 telephone call) or to ask not to

sumers were met with the strongest levels of disagreement. Con- receive future advertisements (mean 2.43 online mail; 1.72 offline

sumers generally were not very interested in the products in mail, 3.53 telephone call). Nor did they request more information

personalized advertising; interest was strongest for products in about the product being advertised (mean 1.35 online mail; 1.74

personalized advertisements delivered via offline mail (3.07) and offline mail; 1.81 telephone call).

weakest if the advertisement was delivered via a telephone call

(1.84). The strongest level of disagreement was for the statement

‘When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I feel I am (RQ3) Perceptions about privacy and

being treated with special care’. Respondents were more negative personalized advertising

about a telephone call (mean 1.63) than online mail (1.45) or The scores for all of the statements concerning privacy and per-

offline mail (2.09). sonalized advertising were greater than 3.0, indicating an overall

negative relationship between personal privacy and personalized

advertising (see Table 3). Answers to three of the five statements

(RQ2) Self-reported responses to personalized

were significantly different at the P < 0.01 or the P < 0.05 level.

advertising

Respondents generally thought that advertisers were violating

Regarding the consumers’ typical response to personalized adver- their privacy (mean 3.65 online mail; 2.99 offline mail; 3.63 tele-

tising, many participants agreed that they reject it immediately phone call) by delivering personalized messages. Also, they

(mean 4.18 online mail; 3.04 offline mail; 3.72 telephone call) (see worried about what other personal information advertisers might

Table 2). The differences by media type were significant in the have (mean 3.70 online mail; 3.46 offline mail; 3.58 telephone

t-tests at the P < 0.01 level. Also, most participants answered that call). Participants generally agreed that acquiring their e-mail

they were not willing to open unsolicited e-mail or mail or to listen addresses/mailing addresses/telephone numbers without any

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 507

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

Table 2 Actual response to personalized advertising

Gender Media

Statement Mean difference difference

When I receive personalized advertising that has my name in the title from an advertiser (company, P < 0.01

brand, store, people) who I don’t know, I am willing to open it and read it (listen to it).

Online mail 1.95

Offline mail 3.32

Telephone call 1.81

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I delete it (throw away, hang up) immediately. P < 0.01

Online mail 4.18

Offline mail 3.04 P < 0.05 (male)

Telephone call 3.72

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I have sent an email (mail, called back) to an P < 0.01

advertiser demanding to know how they got my personal information.

Online mail 1.60

Offline mail 1.62 P < 0.05 (male)

Telephone call 2.23

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I have sent an e-mail (mail, called back) to an P < 0.01

advertiser asking them not to send (call) advertisements to me anymore.

Online mail 2.43 P < 0.05 (female)

Offline mail 1.72

Telephone call 3.53

When I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I have sent an e-mail (mail, called back) to an P < 0.01

advertiser asking for more information about the product being advertised.

Online mail 1.35 P < 0.01 (male)

Offline mail 1.74

Telephone call 1.81

Table 3 Privacy concerns and personalized advertising

Gender Media

Statement Mean difference difference

When I receive personalized advertising that includes my name from an advertiser (company,

brand, store, people) who I don’t know, I believe my information can be accessed by all

advertisers if they want it.

Online mail 3.64

Offline mail 3.62

Telephone calls 3.65 P < 0.05 (female)

When I receive personalized advertising, I feel my privacy has been violated. P < 0.01

Online mail 3.65

Offline mail 2.99

Telephone calls 3.63 P < 0.05 (female)

When I receive personalized advertising, I don’t consider my e-mail address (address,

telephone number) to be private.

Online mail 3.45

Offline mail 3.38

Telephone calls 3.42

When I receive the personalized advertising, I am worried about what other information P < 0.05

about me they also have.

Online mail 3.70 P < 0.05 (female)

Offline mail 3.46

Telephone calls 3.58

When I receive the personalized advertising, I think getting e-mail addresses (address, P < 0.05

telephone number) without any authorization is a type of crime.

Online mail 3.07

Offline mail 2.79

Telephone calls 3.02

508 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

H.J. Yu and B. Cude Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising

Table 4 Attitude towards advertiser in personalized advertising and purchase intentions

Gender Media

Statement Mean difference difference

When I receive personalized advertising including my name from an advertiser (company, P < 0.01

brand, store, people) who I don’t know, I feel terrible about this advertiser.

Online mail 3.52

Offline mail 2.88

Telephone calls 3.55

After I receive personalized advertising, I have made purchases from the advertiser who sent P < 0.01

me the e-mail (direct mail, calling).

Online mail 1.71

Offline mail 2.60

Telephone calls 1.83

When I have received personalized advertising, I have told my friends or family not to buy P < 0.01

products from the advertiser.

Online mail 2.20

Offline mail 2.13

Telephone calls 2.50 P < 0.05 (male)

After getting this kind of personalized advertising, I am likely to buy from this advertiser. P < 0.01

Online mail 1.84

Offline mail 2.40

Telephone calls 1.92

After getting this kind of personalized advertising, I don’t trust the advertiser and its products, P < 0.01

because they got my e-mail address (address, telephone number) without my knowledge.

Online mail 3.42

Offline mail 2.91

Telephone calls 3.43

authorization is a type of crime (mean 3.07 online mail; 2.79 polarised into (1) favourable to personalized advertising, and (2)

offline mail; 3.02 telephone call). In general, their concern about not favourable to personalized advertising.

privacy was stronger for online mail and telephone calls than for As seen in the fourth column of Tables 1–4, there were sig-

offline mail. nificant differences among 18 of the 20 questions by type of

media used to deliver the advertising, and 16 out of 18 were

(RQ4) Consumers’ intentions to purchase the significant at the P < 0.01 level. Based on the results from the

product advertised one-way anovas, the Post hoc (Bonferroni) test was conducted to

learn more detailed information about the differences among the

Overall, consumers’ intentions to purchase the products in person-

three different types of personalized advertising. In general, par-

alized advertising were low (see Table 4). The mean scores

ticipants were less negative about personalized advertising deliv-

indicated that personalized advertisements generated negative atti-

ered via offline mail than about advertising delivered via either

tudes towards the advertisers (mean 3.42 online mail; 2.91 offline

of the other two types of media (Table 1–4). Differences were

mail; 3.43 telephone call) and caused mistrust in the advertisers

significant at the P < 0.01 level. For example, the participants

(mean 3.52 for online mail; 2.88 offline mail; 3.55 telephone call).

strongly agreed with the statements, ‘When I receive that kind of

All differences by media type were significant at the P < 0.01

personalized advertising, even though it is an unfamiliar adver-

level. In addition, mean scores were very low for having purchased

tiser, I will be interested if it is about a product I like’ and ‘When

a product advertised in personalized advertisements (mean

I receive that kind of personalized advertising, I feel I am being

ranging from 1.71 for online mail to 2.60 for offline mail) and

treated with special care’ if the media were offline mail. On the

intentions to buy advertised products in this way (1.84 for online

other hand, the answers to these statements were more negative

mail to 2.40 for offline mail). Respondents were generally unlikely

if the medium used to deliver the advertising was an e-mail or

to recommend products promoted via personalized advertisements

a phone call. Participants were also significantly more likely to

to others (means of 2.13 to 2.50 across the three media types).

read personalized advertising in a letter than to read an e-mail or

listen to a phone call.

(RQ5) Different attitudes towards personalized

However, there were fewer differences by media type among

advertising among the three media types

participants’ answers to the questions dealing with privacy issues

To examine differences in participants’ answers by type of media, (see Table 3). The three items that were significantly different

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used. Nega- indicated that respondents were somewhat less concerned about

tively worded items were re-coded before conducting the their privacy when personalized advertising was delivered via

ANOVAs. After the reverse coding, all the answers could be offline mail compared to e-mail or a phone call.

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 509

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

The significant influences of the three independent variables

(RQ6) Gender differences and attitudes

(general perceptions of personalized advertising, actual responses

towards personalized advertising

to personalized advertising and privacy concerns) on the partici-

There were significant differences between the answers of males pants’ purchase intentions of the product advertised also were

and females in only 10 of the 60 statements (see Tables 1–4). found for offline personalized advertising (Table 6) and telephone

T-tests indicated that women felt more uncomfortable about per- calls (Table 7). In other words, the results of the regression analy-

sonalized advertising than males (see Table 1, P < 0.01). However, ses clearly showed that there were not meaningful differences

women were more likely to agree with the statement, ‘When I among the three types of personalized advertising in terms of the

receive that kind of e-mail, I feel I am being treated with special relationship between intentions to purchase the product advertised

care’ (see Table 1, P < 0.05). Women were also more likely than and the three independent variables (general perceptions of per-

men to say they respond to a personalized advertisement by asking sonalized advertising, actual responses to personalized advertising

not to receive the advertising in the future (see Table 2, P < 0.05). and privacy concerns).

Females were more concerned than males about the possibility

that the advertiser might have other personal information about

Discussion

them (see Table 3, P < 0.05) and to feel that personalized adver-

tising violates their privacy (see Table 3, P < 0.05).

Rethinking personalized advertising

Male respondents were more likely than females to say they

immediately reject a personalized advertisement and to demand to Marketers worldwide have spent large sums of money to create

know how the advertiser got their personalized information (see and deliver personalized advertising (Low, 2000; Kim et al., 2001;

Table 2, P < 0.05). Interestingly, males were more likely to say Pramataris et al., 2001; Gurau et al., 2003) with the general belief

they request information about the product being advertised (see that the advertisement will be more effective because it is person-

Table 2, P < 0.01). In a contradictory finding, males also were alized (Roehm and Haugtvedt, 1999; Pavlou and Stewart, 2000).

more likely than females to say they tell family or friends not to However, this study revealed that personalized advertising deliv-

buy from the advertiser involved in a personalized advertisement ered via all three types of media generated more negative than

(see Table 4, P < 0.05). positive effects among the respondents. Although there were some

exceptions, participants tended to not like receiving personalized

advertising. The results clearly suggested that all marketers should

(RQ7) Influence of general perceptions of

think seriously about the possible negative effects of personalized

personalized advertising, actual responses

advertising before using it. In the case of online personalized

to personalized advertising and privacy

advertising, the most typical response from participants was to

concerns on the purchase intentions of the

delete the advertisement before even opening it. Therefore,

product advertised

smarter ways to create and send customized messages online

To answer this research question, a series of hierarchical logistic require special effort on the part of the company, as the targeted

regression analyses was performed using the three independent consumer may see it as junk e-mail and delete it without even

variables (general perceptions of personalized advertising, actual reading it.

responses to personalized advertising, and privacy concerns). The Actually, consumers’ general avoidance of online advertising

dependent variable was the participants’ intentions to purchase the is evident in the current literature (Jin and Villegas, 2007) and is

product advertised. Each of the independent variables significantly a worldwide trend (Hoeken et al., 2003). For example, Cho and

influenced consumers’ intentions to purchase the product adver- Cheon (2004) found that consumers from both western and eastern

tised when personalized advertising was delivered online (see countries generally avoid online advertising messages. They sug-

Table 5). gested three important variables that cause advertising avoidance

Table 5 Online personalized advertising

Predictors B

Model 1 General perceptions about personalized advertising 0.501*

Adjusted R square 0.247

d.f. = 1, MS = 15.420, F = 65.076, P = 0.000

Model 2 General perceptions about personalized advertising and responses to the personalized advertising 0.444*

Adjusted R square 0.287

d.f. = 1, MS = 9.045, F = 40.316, P = 0.000

Model 3 General perceptions about personalized advertising, responses to the personalized advertising, and 0.303*

consumers’ privacy concerns

Adjusted R square 0.331

d.f. = 1, MS = 6.985, F = 33.167, P = 0.000

Hierarchical regression for predicting consumers’ attitude towards the advertisers/purchase intention using three variables (general perceptions about

personalized ads, actual responses and privacy concerns).

DV, Consumers’ attitude towards the advertisers/purchase intention, *P < 0.01.

510 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

H.J. Yu and B. Cude Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising

Table 6 Letter/package personalized advertising

Predictors B

Model 1 General perceptions about personalized advertising 0.559

Adjusted R square 0.308

d.f. = 1, MS = 19.878, F = 87.539, P = 0.000

Model 2 General perceptions about personalized advertising and responses to the personalized advertising 0.531

Adjusted R square 0.364

d.f. = 1, MS = 11.799, F = 56.490, P = 0.000

Model 3 General perceptions about personalized advertising, responses to the personalized advertising, 0.389

and consumers’ privacy concerns

Adjusted R square 0.404

d.f. = 1, MS = 8.765, F = 44.750, P = 0.000

Hierarchical regression for predicting consumers’ attitude towards the advertisers/purchase intention using three variables (general perceptions about

personalized ads, actual responses and privacy concerns).

Table 7 Telephone personalized advertising

Predictors B

Model 1 General perceptions about personalized advertising 0.583

Adjusted R square 0.336

d.f. = 1, MS = 23.493, F = 98.298, P = 0.000

Model 2 General perceptions about personalized advertising and responses to the personalized advertising 0.523

Adjusted R square 0.381

d.f. = 1, MS = 13.407, F = 60.179, P = 0.000

Model 3 General perceptions about personalized advertising, responses to the personalized advertising, 0.373

and consumers’ privacy concerns

Adjusted R square 0.421

d.f. = 1, MS = 9.916, F = 47.577, P = 0.000

Hierarchical regression for predicting consumers’ attitude towards the advertisers/purchase intention using three variables (general perceptions about

personalized ads, actual responses and privacy concerns).

through their cross-cultural survey: (1) perceived goal impedi- favourable responses towards delivery via offline mail than the

ment, (2) perceived ad clutter, and (3) prior negative experience. other two types of media. They were less likely to reject the mail

Among those, the authors found that perceived goal impediment immediately, more likely to take it seriously, less threatened by the

was the most significant reason people generally wanted to avoid personalized advertisement as a violation of their privacy, and

online advertising. In many cases, online users have their own somewhat more likely to view it as personal attention. Actually,

goals when they access the Internet. Therefore, they pay little or no these results support the conclusions of some researchers (e.g.

attention to online advertising that is not related to their task. In Trollinger, 2006) who have suggested that companies need to

addition, a fourth negative influence is present for those who view balance online personalized advertising with traditional personal-

the advertising as an invasion of their privacy (Sheehan, 1999). ized advertising in their marketing efforts. Consumers may find

This study presents the dilemma posed by personalized adver- traditional mail less threatening because if one opens it and finds

tising for both marketers and consumers. How can marketers it uninteresting, it can be thrown away and no harm is done.

convey personalized advertising messages without giving the However, it may not be as easy to end a phone call with a telemar-

offensive impression of violating their customers’ privacy? How keter or to deal with the after effects of opening an e-mail that

can consumers take advantage of advertising tailored to their inter- potentially contains a harmful virus or worm.

ests and still protect their privacy? It is the right time for a more In general, personalized advertising delivered via a phone call

comprehensive discussion about how to deliver personalized generated the most negative response, as well as privacy concerns

advertising for a net positive effect. Future research could explore equal to those about online advertising. Approximately 100

various avenues including copy testing, creating less intimidating million telephone numbers are registered in the US ‘Do Not Call

titles for e-mails, or asking for pre-consent before sending person- Registry’, and more than half of the states in the US have with-

alized advertising to consumers. drawn their Motor Vehicle Registry data from marketing use

(Marketing News, 2006). Researchers in multiple countries have

concluded that phone calls no longer seem to be an effective

The differences among the three media and

delivery option for personalized advertising (Hoeken et al., 2003).

gender’s influence

The results also confirmed the findings of previous researchers

Among the three types of media used to deliver personalized (Sheehan, 1999; Wolin and Korgaonkar, 2005) that females are

advertising, this study’s respondents showed comparably more more concerned about privacy than males. However, it is unclear

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 511

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

why this is the case. Do the differences actually reflect differences Using the findings of this research as a springboard, one of the

in experience, especially online? Or do they reflect differences in next steps could be to establish a scale to more accurately reflect

willingness to trust or other psychographic variables? This area is consumers’ different insights on diverse types of personalized

one for further exploration. advertising. In addition, the questionnaire used in this study did

not include questions about personalized advertising delivered as a

text-message through mobile phones which have been a popular

Public policy and personalized advertising

type of personalized ads (Nantel and Sekhavat, 2008). Thus, future

Many of the US consumers who completed the survey agreed that studies about personalized advertising should include new and

using one’s personal contact information to deliver personalized popular styles of personalized advertising.

advertising without any authorization ‘is a type of crime’. In fact, Lastly, additional research is needed to explore ways in which

in the US, there are few legal restrictions on businesses’ ability to companies can use personalized advertising without alienating

collect and use or even sell personal information. An exception consumers who feel that the advertising violates their privacy.

is the US Do Not Call Registry; there are significant fines for Because the current study did not explore what consumers like

telemarketers who call consumers who have registered their tele- and do not like about personalized advertising, the results could

phone numbers with this list. The FTC’s proposed guidelines for not provide useful information about how marketers could design

self-regulation when conducting personalized advertising include personalized advertising to be less offensive style to those con-

an expectation that any company collecting or storing consumers’ cerned about personal privacy. Thus, an alternative approach for

private information should provide reasonable security for that future researchers would be to use an experimental design to

information, and should retain the data only as long as is necessary better understand what personalized advertisements communicate

to fulfil a legitimate business or law enforcement need (The Com- to consumers. Personalized advertisements in the experiments

puter & Internet Lawyer, 2008). The FTC also has recommended should be diverse in terms of types of media used to deliver them,

that companies only collect an individual’s information for per- the message style, the e-mail subject line and so forth. In addi-

sonalized advertising if they obtain affirmative, expressed consent tion, it would be interesting to compare the effectiveness of an

from the consumer to receive such advertising. explicitly personalized advertisement (‘Dear Mr. Smith: Look at

In contrast to the US approach of no national policy on privacy, this option for your new Toyota Camry!’) vs. one that matches

the European Union (EU) has adopted strict rules, with mecha- the consumer’s personal interests but is not explicitly personal-

nisms for global enforcement. The EU rules require retailers to ized (‘Look at this option for a new Toyota Camry’). Creating

seek consumers’ permission before they collect and use personal personalized advertising without violating privacy may not

data in their own marketing, trade it to partners or sell it. In the EU, be easy; however, the efforts could pay off for marketers and

how much information and how long it can be kept is restricted consumers.

and consumers have open access to data about themselves and the

right to collect any inaccuracies. Privacy laws modelled after those

in the EU are now in place in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and References

parts of Asia and Latin America (Stephens, 2007).

Adler, R., Rosenfeld, L., Proctor, II & R. (2004) Interplay: The Process

of Interpersonal communication, 9th edn. Harcourt, Fort Worth, TX.

Limitations and suggestions for Alexander, R. & the Committee on Definitions of the American Market-

future research ing Association. (1960) A Glossary of Marketing Terms. American

Marketing Association, Chicago, IL.

Because the subjects in this study were US college students living Armstrong, G. & Kotler, P. (2000) Marketing: An Introduction. Prentice-

in the southeast, the generalizability of the results to other popu- Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

lations with different demographics could be relatively limited. Bozios, T., Lekakos, G., Skoularidou, V. & Chorianopoulos, K. (2001)

Even though young adults are considered a major consumer group Advanced Techniques for Personalized Advertising in a Digital Envi-

ronment: The iMedia System. Proceedings of the eBusiness and

for diverse product categories not only in the US but also in many

eWork Conference. [WWW document]. URL http://istlab.dmst.aueb.

other countries (Huang, 1998; Sheehan, 1999; Tsang et al., 2004;

gr/~vsko/pubs/confs/ebew2002_paper2.html (accessed on 2 October

Paek, 2005), other consumer groups might respond to personal- 2006).

ized advertisements differently. For example, young adults likely Bulander, R., Decker, M., Schiefer, G. & Kolmel, B. (2005) Compari-

use the Internet and cell phones more than other generations, thus son of Different Approaches for Mobile Advertising. Proceedings of

influencing their perceptions positively or negatively about per- the 2005 Second IEEE International Workshop on Mobile Commerce

sonalized advertising delivered via e-mail and telephone. In addi- and Services.

tion, consumers in European or Asian countries where policies Caudill, E.M. & Murphy, P.E. (2000) Consumer online privacy: legal

about protecting one’s personal privacy are different than in the and ethical issues. Journal of Public Policy And Marketing, 19, 7–19.

US could have different opinions about personalized advertising. Chachko, P. (2004) Reaching out to customers through e-mail and data-

base marketing. Franchising World, 36, 16–17.

Therefore, future studies should consider using a more diverse

Chaudhuri, A. & Buck, R. (1995) Media differences in rational and

sample of consumers with different demographic characteristics

emotional responses to advertising. Journal of Broadcasting & Elec-

and/or different nationalities. tronic Media, 39, 109–126.

Regarding the measurements, the researchers developed the Cho, C.-H. & Cheon, H.J. (2004) Why do people avoid advertising on

questionnaire for this exploratory study because a single scale to the Internet? The Journal of Advertising, 33, 89–97.

investigate responses to personalized advertising was unavailable. Chorianopoulos, K., Lekakos, G. & Spinellis, D. (2004) The Virtual

Thus, measurement validity may be a limitation of this research. Channel Model for Personalized Television. Proceedings of the

512 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

H.J. Yu and B. Cude Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising

EuroiTV2003, UK, Brighton. [WWW document]. URL http://www. Long, G., Hogg, M.K., Hartley, M. & Angold, S.J. (1999) Relationship

brighton.ac.uk/interactive/euroitv/euroitv03/Papers/Paper7.pdf marketing and privacy: exploring the thresholds. Journal of Marketing

(accessed on 10 October 2006). Practice: Applied Marketing Science, 5, 4–20.

Consumers International (2002) Credibility on the Web: An International Low, G.S. (2000) Correlates of integrated marketing communications.

Study of the Credibility of Consumer Information on the Internet. Journal of Advertising Research, 40, 27–39.

Office for Developed and Transition Economies. M2PressWIRE (2006) Direct Mail Advertising in the US by IBIS World,

Cutler, Bob D. & Thomas, Edward D. (2000) Informational/ Feb 14, 2006. [WWW document]. URL http://www.mindbranch.com/

transformational advertising: differences in usage across media types, products/R538 (accessed on 2 Oct 2006).

product categories; and national cultures. Journal of International Mabley, K. (2000) Privacy vs. personalization. Cyber Dialogue. [WWW

Consumer Marketing, 12, 69–84. document]. URL http://www.cyberdialogue.com/library/pdfs/wp-cd-

Foxman, E. & Kilcoyne, P. (1993) Information technology, marketing 2000-privacy.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2006).

practice, and consumer privacy: ethical issues. Journal of Public McKeen, J.D., Gulmaraes, T. & Wetherbe, J.C. (1994) The relationship

Policy and Marketing, 12, 106–119. between user participation and user satisfaction: an investigation of

Friedman, B. & Vincent, S. (2005) Growing with web-based one-to-one four contingency factors. MIS Quarterly, 18, 427–451.

marketing. CPA Practice Management Forum, 1, 10–23. Marketing News (2006) Outlook 2006. January 15, 16.

Gal-Or, E. & Gal-Or, M. (2005) Customized advertising via a common Miyazaki, A.D. & Fernandez, A. (2000) Internet privacy and security:

media distributor. Marketing Science, 24, 241–253. an examination of online retailer disclosures. Journal of Public Policy

Gao, Z. (2005) Harmonious regional advertising regulation? A compara- & Marketing, 19, 54–61.

tive examination of government advertising regulation in China, Hong Morimoto, M. & Chang, S. (2006) Consumers’ attitude toward unsolic-

Kong, and Taiwan. Journal of Advertising, 34, 75–87. ited commercial e-mail and postal direct mail marketing methods:

Gurau, C., Rachhod, A. & Gauzente, C. (2003) To legislate or not to intrusiveness, perceived loss of control, and irritation. Journal of

legislate: a comparative exploratory study of privacy/personalization Interactive Advertising, 7, 8–20.

factors affecting French, UK and US websites. Journal of Consumer Moschis, G.P. & Moore, R.L. (1979) Family communication and con-

Marketing, 20, 652–664. sumer socialization. Advances in Consumer Research, 6, 359–363.

Hoeken, H., van den Brandt, C., Crijns, R., Dominguez, N., Hendriks, Nantel, J. & Sekhavat, Y. (2008) The impact of SMS advertising on

B., Planken, B. & Starren, M. (2003) International advertising members of a virtual community. Journal of Advertising Research,

in western europe: should differences in uncertainty avoidance be September, 363–374.

considered when advertising in Belgium, France, The Netherlands Nathanson, A.I. (1999) Identifying and explaining the relationship

and Spain? Journal of Business Communication, 40, 195– between parental mediation and children’s aggression. Communica-

218. tion Research, 26, 124–143.

Howard, D. & Kerin, Roger A. (2004) The effects of personalized Nowak, G.J., Shamp, S., Hollander, B. & Cameron, G.T. (1999) Interac-

product recommendations on advertisement response rates: the ‘Try tive media: a means for more meaningful advertising? In Advertising

This. It Works!’ technique. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 14, and the World Wide Web (ed. by D.W. Schumann & E. Thorson), pp.

271–279. 99–117. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ.

Huang, M.-H. (1998) Exploring new appeals: basic, versus social, emo- O’Leary, C., Rao, S. & Perry, C. (2004) Improving customer relationship

tional advertising on a global setting. International Journal of Adver- management through database/Internet marketing: a theory-building

tising, 17, 145–169. action research project. European Journal of Marketing, 38, 338–354.

Jin, C.H. & Villegas, J. (2007) Consumer responses to advertising on the Paek, H.-J. (2005) Understanding celebrity endorsers in cross-cultural

Internet: the effect of individual difference on ambivalence and avoid- contexts: a content analysis of South Korean and U.S. newspaper

ance. Cyber Psychology & Behavior, 10, 258–266. advertising. Asian Journal of Communication, 15, 133–153.

Kazienko, P. & Adamski, M. (2007) AdROSA-adaptive personalization Palmatier, R.W., Dant, R.P., Grewal, D. & Evans, K.R. (2006) Factors

of web advertising. Information Sciences, 177, 2269–2295. influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: a meta-

Kim, J.W., Lee, B.H., Shaw, M.J., Chang, H.-L. & Nelson, M. (2001) analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70, 136–153.

Application of decision-tree induction techniques to personalized Pavlou, P.A. & Stewart, D.W. (2000) Measuring the effects and effec-

advertisements on Internet storefronts. International Journal of Elec- tiveness of interactive advertising: a research agenda. Journal of Inter-

tronic Commerce, 5, 45–62. active Advertising, 1, 1–27.

Kim, J.K. & Pasadeos, Y. (2007) Ad Avoidance by Audiences across Pereira, M.A., Kartashov, A.I., Ebbeling, C.B., Van Horn, L., Slattery,

Media: Modeling Beliefs, Attitudes and Behavior toward Advertising. M.L., Jacobs, D.R., Jr. & Ludwig, D.S. (2005) Fast-food habits,

American Academy of Advertising, Annual Conference, Burlington, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year pro-

Vermont. spective analysis. Lancet, 365, 36–42.

King, N. (2008) Direct marketing, mobile phones, and consumer Perreault, W.D., Jr. & McCarthy E.J. (1999) Basic Marketing: A Global-

privacy: ensuring adequate disclosure and consent mechanisms for Managerial Approach, 13th edn. McGraw-Hill Publishing, New York.

emerging mobile advertising practices. Federal Communications Law Petty, R.E. & Cacioppo, J.T. (1986) Communication and Persuasion:

Journal, 60, 229–324. Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. Springer-Verlag,

Krugman, H.E. (1965) The impact of television advertising: New York.

learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29, 349– Phelps, J.E., D’Souza, G. & Nowak, G.J. (2001) Antecedents and conse-

356. quences of consumer privacy concerns: an empirical investigation.

Lekakos, G. & Giaglis, G.M. (2004) A lifestyle-based approach for Journal of Interactive Marketing, 15, 2–17.

delivering personalized advertisements in digital interactive television. Poon, S. & Jevons, C. (1997) Internet-enabled international marketing: a

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 9, No Pagination small business network perspective. Journal of Marketing Manage-

Specified. ment, 13, 29–41.

Li, H., Daugherty, T. & Biocca, F. (2002) Impact of 3-D advertising on Pramataris, K., Papakyriakopoulos, D.A., Lekakos, G. & Mylonopoulos,

product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: the medi- N.A. (2001) Personalized interactive TV advertising: the iMedia busi-

ating role of presence. Journal of Advertising, 31, 43–57. ness model. Electronic Markets, 11, 17–25.

International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514 513

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Consumers’ perceptions about personalized advertising H.J. Yu and B. Cude

Rodgers, S. & Thorson, E. (2000) The interactive advertising model: Trollinger, S. (2006) Striking a balance between e-mail and traditional

how users perceive and process online ads. Journal of Interactive direct marketing. Ingram’s, 32, 57.

Advertising, 1, [WWW document]. URL http://www.jiad.org/vol1/ Tsang, M.M., Ho, S.-C. & Liang, T.-P. (2004) Consumer attitudes

no1/rodgers/index.htm (accessed on 6 October 2006) toward mobile advertising: an empirical study. International Journal

Roehm, H. & Haugtvedt, C. (1999) Understanding interactivity of cyber- of Electronic Commerce, 8, 65–78.

space advertising. In Advertising and the World Wide Web (ed. by UPI-Zogby International Poll (2007) UPI Poll: Don’t suspend privacy

D.W. Schumann & E. Thorson), pp. 27–39. Lawrence Erlbaum rights – Zogby/UPI Polls. [WWW document].

Associates, Mahwah, NJ. URL http://www.zogby.com/index.cfm (accessed on 6 April 2008).

Rosenberg, J.M. (1995) Reinventing Advertising. Speech presented at U.S. Federal Trade Commission (2000) Privacy Online: Fair Informa-

the Groupe d’Ouchy (22 June). tion Practices in the Electronic Marketplace. A Report to Congress,

Rotfeld, H.J. (2006) Understanding advertising clutter and the real solu- May.

tion to declining audience to mass media commercial messages. U.S. Federal Trade Commission (2009) Self-regulatory Principles for

Journal of Consumer Marketing, 23, 180–181. Online Behavioral Advertising. Tracking, Targeting, & Technology.

Sacirbey, O. (2000) Privacy concerns, advertising hamper E-commerce. FTC Staff Report, February.

IPO Reporter, 24, 11. Ward, S. & Wackman, D. (1973) Children’s information processing of

Sasser, S.L., Koslow, S. & Riordan, E.A. (2007) Creative and interactive television advertising. In New Models for Mass Communication

media use by agencies: engaging an IMC media palette for imple- Research (ed. by P. Clarke). Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA.

menting advertising campaigns. Journal of Advertising Research, Wehmeyer, K. (2005) Aligning IT and marketing – the impact of data-

September, 237–256. base marketing and CRM. Journal of Database Marketing & Cus-

Sheehan, K.B. (1999) An investigation of gender differences in on-line tomer Strategy Management, 12, 243–256.

privacy concerns and resultant behaviors. Journal of Interactive Mar- Wolburg, J. & Kim, H. (1998) Messages of individualism and collectiv-

keting, 13, 24–38. ism in Korean and American magazine advertising: a cross cultural

Sheehan, K.B. (2005) In poor health: an assessment of privacy policies study of values. 1998 American Academy of Advertising Proceedings,

at direct-to-consumer web sites. Journal of Public Policy & Market- 147–154.

ing, 24, 273–283. Wolin, L. & Korgaonkar, P. (2005) Web advertising: gender differences

Sheehan, K.B. & Hoy M.G. (1999) Flaming, complaining, abstaining: in beliefs, attitudes, and behavior. Journal of Interactive Advertising,

how online users respond to privacy concerns. Journal of Advertising, 6, 125–136.

28, 37–52. Wu, S.-I. (2006) The impact of feeling, judgment and attitude on

Sheehan, K.B. & Gleason, T.W. (2001) Online privacy: Internet advertis- purchase intention as online advertising performance measure.

ing practitioners’ knowledge and practices. Journal of Current Issues Journal of International Marketing & Marketing Research, 31,

and Research in Advertising, 23, 31–41. 89–108.

Stephens, D.O. (2007) Protecting personal privacy in the global business Xu, D.J., Liao S.S. & Li, Q. (2008) Combining empirical experimenta-

environment. The Information Management Journal, 41, 56–59. tion and modeling techniques: a design research approach for person-

Stewart, D.W. & Ward, S. (1994) Media effects on advertising. In Media alized mobile advertising applications. Decision Support Systems, 44,

Effects: Advances in Theory and Research (ed. by J. Bryant & D. 710–724.

Zillmann), pp. 315–363. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc, Hillsdale, Yu, J.H., Paek, H.-J. & Bae B. (2008) Cross-cultural comparison of

NJ. interactivity and promotional appeals in the U.S. and South Korean

Sundar, S.S. & Kim, J. (2005) Interactivity and persuasion: influencing antismoking websites. The Journal of Internet Research, 18, 454–476.

attitudes with information and involvement. Journal of Interactive Yuan, S.-T. & Tsao, Y.W. (2003) A recommendation mechanism for con-

Advertising, 5, [WWW document]. URL http://www.allacademic.com/ textualized mobile advertising. Expert Systems with Applications, 24,

meta/p113152_index.html (accessed on 15 October 2006). 399–414.

514 International Journal of Consumer Studies 33 (2009) 503–514

Journal compilation © 2009 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Mohammed Saabir CVDokument2 SeitenMohammed Saabir CVsabirbdkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk Assessment For Installation of Automatic Revolving Door InstallationDokument8 SeitenRisk Assessment For Installation of Automatic Revolving Door Installationsabirbdk100% (1)

- Women EntreprenuershipDokument2 SeitenWomen EntreprenuershipsabirbdkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Year Degree Institution Board/ University Specializati On % AgeDokument3 SeitenYear Degree Institution Board/ University Specializati On % AgesabirbdkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Satisfaction of JewelleryDokument71 SeitenCustomer Satisfaction of Jewellerysabirbdk67% (6)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- MQTT ProtocolDokument8 SeitenMQTT ProtocolrajzgopalzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hospital Fernando Fonseca's Case Study: IntranetDokument2 SeitenHospital Fernando Fonseca's Case Study: IntranetPedro SerranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of DatabasesDokument9 SeitenHistory of Databaseskira3003Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Ordem de Cristo Tomar Vieira de Guimaraes PDFDokument402 SeitenA Ordem de Cristo Tomar Vieira de Guimaraes PDFRicardo SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Booking Reference:: 7U08DY Dubai To AmmanDokument2 SeitenBooking Reference:: 7U08DY Dubai To AmmanMohamed AzimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacts of COVID-19 On Organisations - Cyber Security Considerations-1Dokument16 SeitenImpacts of COVID-19 On Organisations - Cyber Security Considerations-1JehanzaibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Guide - Proper Shimming - Filipino Airsoft (FAS) - ForumDokument8 SeitenComplete Guide - Proper Shimming - Filipino Airsoft (FAS) - ForumAmeer Marco LawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 7 - Network 2022Dokument24 SeitenChapter 7 - Network 2022JI TENNoch keine Bewertungen

- En - Security Center Installation and Upgrade Guide 5.7 SR3Dokument192 SeitenEn - Security Center Installation and Upgrade Guide 5.7 SR3Patricio Alejandro Aedo AbarcaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 06Dokument169 Seiten06leo001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nptel Previous Year QurestionsDokument23 SeitenNptel Previous Year Qurestionssanskritiagarwal2022Noch keine Bewertungen

- Designing JSP Custom Tag LibrariesDokument23 SeitenDesigning JSP Custom Tag Librariestoba_sayed100% (3)

- MRB 137 Evo Manuli CrimpDokument1 SeiteMRB 137 Evo Manuli Crimpjhon peñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solucion Jave RBS Element ManagerDokument3 SeitenSolucion Jave RBS Element Managermanulink1100% (3)

- Admission BookletDokument38 SeitenAdmission BookletMmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding The Basic Concept in ICTDokument32 SeitenUnderstanding The Basic Concept in ICTRich Comandao100% (2)

- SESSION2Dokument14 SeitenSESSION2shadab BenawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual Sensor Net Connect V2Dokument27 SeitenManual Sensor Net Connect V2África RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi Protocol Gateway Developers GuideDokument416 SeitenMulti Protocol Gateway Developers Guidenaveen25417313Noch keine Bewertungen

- DGMS Circular 2014 PDFDokument21 SeitenDGMS Circular 2014 PDFSheshu Babu100% (1)

- CEH v8 Labs Module 03 Scanning NetworksDokument182 SeitenCEH v8 Labs Module 03 Scanning NetworksDeris Bogdan IonutNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20341a Alllabs PDFDokument68 Seiten20341a Alllabs PDFmasterlinh2008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ds 1664 SMDokument4 SeitenDs 1664 SMWumWendelin0% (1)

- OTA105105 OptiX OSN 1500250035007500 Hardware Description ISSUE 1.13Dokument185 SeitenOTA105105 OptiX OSN 1500250035007500 Hardware Description ISSUE 1.13karthiveeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANDROIDDokument13 SeitenANDROIDJoanna Cristine NedicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Upgrade Mikrotik Version 3.20 To Version 3.30 Level 6 (English Version)Dokument9 SeitenUpgrade Mikrotik Version 3.20 To Version 3.30 Level 6 (English Version)Ed Carlos RiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0000 Stats PracticeDokument52 Seiten0000 Stats PracticeJason McCoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Networking Essentials 2.0 CapstoneDokument10 SeitenNetworking Essentials 2.0 CapstoneJoshua CastromayorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Software Engineering Chapter 6 ExercisesDokument4 SeitenSoftware Engineering Chapter 6 Exercisesvinajanebalatico81% (21)

- Social Media For MusiciansDokument24 SeitenSocial Media For MusiciansTuneCore100% (1)