Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rethinking Gender and Violence - Agency Heterogeneity and Intersectionality PDF

Hochgeladen von

Saly WazzeOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rethinking Gender and Violence - Agency Heterogeneity and Intersectionality PDF

Hochgeladen von

Saly WazzeCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.

Rethinking Gender and Violence: Agency, Heterogeneity,

and Intersectionality

S.J. Creek* and Jennifer L. Dunn

Department of Sociology, Southern Illinois University Carbondale

Abstract

This paper is a consideration of the increasing diversity of images of gender violence and its vic-

tims, as both the grassroots antiviolence activists, and the scholars of the movements and the vio-

lence that inspires the activism, engage with cultural codes and feeling rules that tend to narrow

the criteria for what constitutes gender violence and victimization. We are coming to better

understand that social location, including but not limited to positions within patriarchal systems of

stratification, shapes violence and victimization in many different ways. Since the inception of the

women’s movement, the discourse of victimization has grappled with the implications of con-

structing ‘pure victims’, and despite the tremendous progress in the resources available to survivors

of gender violence, we find the tensions between victimization and agency, and between simplic-

ity and complexity, reemerging repeatedly in the stories victims, activists, and scholars tell about

this social problem. Below, we review the sociological research and activism, in conjunction with

the collective narratives in the social movements against gender violence, to show how the issues

of perceptions of women who are framed as victims began and remain central to feminist research

in this area. We also explore the newest visions of gender violence, that broaden theorizing and

activism to include multiple dimensions of inequality and their intersections. Taken together, these

debates reveal multifaceted layers of complexity that inform the contexts and lived experience of

violence, and that continue to enter into our storytelling.

In this paper, we review and reflect upon the development of activist, scholarly, and

everyday understandings of gender violence and especially of its victims. We are

increasingly learning that social location, importantly but not solely within patriarchal

systems of stratification, shapes violence and victimization in complex ways. We have

also been attending more closely to the consequences of images of violence and victim-

ization for identification of and responses to the abuse of the less powerful members

of society. We begin with a brief review of the research and role of sociologists in

the early years of the anti-rape, battered women’s, and child sexual abuse survivor

movements, and some constructions of gender violence that emerged as a conse-

quence. We then explore debates about agency and victimization in the context of

gender violence. Concerns about the limitations of ‘either ⁄ or’ constructions of gender

violence victims inspire further venturing into feminist scholarly arguments that pre-

vailing typifications of gender violence – even now – do not capture the heterogene-

ity of actual, everyday victims and victimization. Finally, we explore new visions of

gender violence emerging out of these debates and the increasing awareness in sociol-

ogy that people stand at the intersection of social forces and structures. These typifica-

tions broaden theorizing and activism to include multiple dimensions of inequality and

their interrelationships, and new categories of interest, including state-sanctioned

violence against men of color.

ª 2011 The Authors

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

312 Gender and Violence

Taken together, these debates reveal layers of complexity that inform the contexts and

lived experience of violence. The study of intimate partner violence, rape, and child sex-

ual abuse is moving beyond gender, ‘pure victims’, and extreme violence to encompass

more nuanced and subtle conceptions and realities. Our object then is not to critique,

but to articulate these various social constructions, in a necessarily brief and partial social

history of the changing discourses of gender violence victimization.

Sociologists researching gender violence

Beginning with the anti-rape movement that emerged out of the consciousness-raising

groups of the early 1970s women’s liberation movement, sociologists have played an

active role in bringing gender violence to the attention of the public and creating images

of victims of rape, battering, and child sexual abuse. Among the best known in the anti-

rape movement is Diana E. H. Russell, who published an influential feminist analysis of

rape based on interviews with victims. As early as 1976, Murray Straus was writing about

‘wife-beating’, and attributes the exponential growth of sociological articles on domestic

violence between 1974 and 1988 to increasing numbers of women, influenced by the

women’s movement, entering graduate school in sociology. Scottish sociologists

R. Emerson Dobash and Russell Dobash articulated patriarchy and wife abuse in 1979.

Mildred Pagelow’s wrote a foundational sociological study published in 1981. David

Finkelhor began publishing on child sexual abuse in 1977 and continues to be prominent

today.

All of these authors were explicitly feminist, explaining gender violence as a function

of patriarchal social structures and as a means of the social control of women and chil-

dren. Due in part to their taking of this stance, they are also united in how they created

images, or ‘typifications’ (Best 1995) that deflected blame from victims. They set out to

counter what they termed widespread prevailing cultural ‘myths’ about what Menachem

Amir (1971) controversially called ‘victim precipitation’ – that is, any notion that victims

were somehow responsible for the crimes committed against them.

By framing victim precipitation in gender violence as mythological, feminist sociolo-

gists in the social movements against rape, and battering, and child sexual abuse shifted

responsibility away from individual victims (and even individual victimizers) and toward

the social structures of patriarchy. In doing this, not only did they assign a different

cause, but they did so in accordance with cultural feeling rules (Hochschild 1979) that

govern toward whom we normally direct our sympathy (Clark 1997). Of necessity,

they created images of innocent victims. Rape victims were never at fault, because they

were helpless to resist, whether it be due to the physical forces arrayed against them or

their own socialization into acquiescent gender roles. Battered women were trapped

by the same social forces and cultural norms, and the child victims of incest even

more so.

This ‘myth-debunking’ (Plummer 1995) was necessary, instrumental, and effective, but

the typification of ‘pure’ and innocent victims has yielded some unintended consequences

(Davies et al. 1998) that have been a source of debate ever since. As early as 1979, Kath-

leen Barry argued that pure victim images narrowly constructed women as the recipients

of violence rather than as actors in their own right. There is a tension adhering to social

constructions of helpless victims, because the lack of agency that defines victimization is a

form of disempowerment. The qualities of victims mirror too closely a traditional femi-

ninity. Feminists in and out of sociology continue to contend with this issue, a discourse

that is the subject of the next section.

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Gender and Violence 313

Victims and agents: the discourse of dichotomy and disempowerment

Beginning with Barry (1979), much scholarly talk of victims has engaged with the need,

on one hand, to show that they are not to blame. As Barry (1979) puts it, ‘Making the

victim responsible for her victimization declares her the cause of her own anguish’ (35).

On the other hand, what Barry (1979) calls ‘new definitions’ can lead to

victimism … which establishes new standards for defining experience; those standards dismiss

any question of will, and deny that the woman even while enduring sexual violence is a living,

changing, growing, interactive person. (38)

For Barry, then, even as a victim complies with a victimizer, she has agency, but not

responsibility – a more complex characterization that accounts for her ‘complicity’ (which

fosters victim-blaming) without completely disempowering her.

Ever since, feminist scholars of gender violence have assiduously argued for the agency

of rape victims and battered women, and the term ‘survivor’ has become a widely used

substitute for ‘victim’ (Dunn 2004, 2005, 2010). In the late 1980s in particular, when Liz

Kelly, a British sociologist, wrote Surviving Sexual Violence (1988) and two books titled

Battered Women as Survivors appeared (Gondolf and Fisher 1988; Hoff 1990), the term

gained popularity. Kelly’s (1988) objective was to shift ‘the emphasis from viewing

women as passive victims of sexual violence to seeing them as active survivors’, because

calling women victims ignores the ways that women ‘resist, cope, and survive’ (163–4).

Gondolf and Fisher (1988) argued that the ‘fundamental assumption’ of their book was to

show that contrary to the ‘helpless and passive victim[s]’ that battered women have been

‘typically characterized’ as, in their efforts to survive, ‘battered women are, in fact, hero-

ically assertive and persistent’ (11, 18). Two years later, in her book (also titled Battered

Women as Survivors), Hoff (1990) describes the women she studied as ‘survivors who

struggled courageously’ (x) rather than ‘merely passive victims’ (1990, 8). Hoff (1990)

presented the women in her study as ‘capable, responsible agents’ (65).

Other scholars have brought the discourse into a consideration of legal realms, where

‘victim contests’ (Holstein and Miller 1990) so frequently play out. For example, sociolo-

gist and expert witness Pamela Jenkins discusses testifying on behalf of battered women

charged with crimes. While recognizing the ‘historical’ tendency to blame women for

their own victimization, Jenkins (1996) critiques the concept of ‘battered woman syn-

drome’ as a perspective that renders women ‘passive’ – ‘trapped by the violence and held

hostage by their own perceptions’ (95–6). In contrast, Jenkins (1996) frames battered

women as, first, agents who are ‘active and courageous’, and ‘determined and brave’,

and, ultimately, as both victims and agents (110).

By constructing battered women this way, Jenkins avoids what Kay Picart (2003) calls

the ‘perniciousness of this binary dichotomy’, which puts women in a ‘double bind’ (97);

in her recent discussion of battered women ‘confronting victim discourses’, Amy Leisen-

ring (2006) similarly refers to the ‘double-bind of victimhood’ for women who simulta-

neously ‘claim’ and ‘reject’ victim identities (315, 326). We also find this double-bind in

the discourse of victim advocates, who assert that ‘everybody makes choices’ even as they

attempt to account for what they see as the ‘bad choices’ made by battered women who

return to their abusers (Dunn and Powell-Williams 2007). So while scholarship may be

identifying and rooting out the source of these identity dilemmas, in practice, they con-

tinue to pose significant problems for victims and for those who would help.

In this brief and selective survey, we can see that since the early days of the social

movements mobilizing against gender violence, scholarly activists have seen that images

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

314 Gender and Violence

of victims as helpless and passive, while averting blame, have potentially disempowering

consequences. At the same time, such conceptions are overly simplistic – no victim is

likely only a victim, or, conversely, if an agent in some ways, thereby not a victim. Alter-

nate conceptualizations of women and children as victims and agents call upon us to dis-

mantle the binary, either ⁄ or structures of our thinking about victims and survivors and

develop ideas that can encompass both ends of a continuum and all that falls between.

Feminist sociologists have gone yet further, however. As Sharon Lamb (1999) points out,

our requirements of victims have also caused us to ‘focus on extreme and pathological

versions’ and a ‘narrow and extreme prototype’ (109). We turn now to scholarship on

discrepancies between idealized typifications of victims in activists’ framing and the ‘het-

erogeneity’ of real victims and their lived experiences (Loseke 1992).

Dismantling the dichotomy and constructing complexity

In looking back at the stories activists in the anti-rape and battered women’s movements

told about victims of these crimes (Dunn 2010), there are some women whose stories

challenge the requirement that victims be ‘pure’ in order to be ‘innocent’. Susan Grif-

fin’s (1971) groundbreaking article in Ramparts tells the story of a stripper raped by the

men attending a bachelor’s party. Griffin makes no comment about the circumstances or

the victims’ occupation, implicitly suggesting that even women likely to be seen as

‘legitimate victims’ (Weis and Borges 1973), i.e. socially acceptable to or deserving of

rape, are true victims. Diana Russell is more explicit. In a chapter of The Politics of Rape

called ‘The Virgin and the Whore’ is the story of a young girl, ‘Rosalind’, who had

been having sex with multiple partners, sometimes on the same occasion, and was even-

tually violently gang-raped by over 20 men. Russell (1975) includes Rosalind’s history

of what many people might call ‘promiscuity’ because she believes that it ‘illustrates very

dramatically what the costs of a sexual double standard can be, and how it can relate to

rape’ (26). But because the interview includes the graphic and horrific details of the gang

rape as well as the earlier promiscuity, the story also can be seen as an example of show-

ing that ‘bad girls’ can still be raped, or, put differently, rape victims can still be bad

girls.

Donileen Loseke has focused her attention on images of battered women, and of some

further unintended implications of activists’ ‘typifications’ (Best 1995). In 1989, in a chap-

ter titled ‘‘‘Violence’’ is ‘‘Violence’’ … or Is It?’, she points to potential disparities

between ‘clear and vivid images of acts and actors’ and ‘real-life events’ that police offi-

cers and others have to interpret in order to decide how to respond (Loseke 1989, 200).

Here and elsewhere, Loseke (1989) argues that the images activists and other claims-mak-

ers create, in part because they are extreme and unambiguous, ‘do not reflect the com-

plexity of social life’ (203). In her study of staff decision-making in a battered women’s

shelter, one consequence was that women whose situations did not conform to relatively

narrow definitions of what constitutes ‘abuse’ could be denied assistance (Loseke 1992).

More recently, Loseke compares the ‘lived realities’ of women participating in a support

group for battered women and the ‘formula stories’ they hear. The formula story, in

which the battered women is necessarily a ‘pure victim trapped in her victimization’ is

problematic because ‘this narrative does not easily encompass the messiness of the lived

experience of troubles in general’ (Loseke 2001, 122, emphasis added).

This messiness is vividly captured in the stories women in prison for violent offenses

against their abusive partners and others told Kathleen Ferraro (2006). Ferraro, who titles

her account and frames these women as ‘neither angels nor demons’, argues that the

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Gender and Violence 315

binary categories of victim and offender are insufficient for understanding how these

women have come to be violent and why. This oversimplification distorts their reality

and obscures the horrific abuse they have endured, and the ‘complicated manner through

which victimization is articulated with criminal offending’ (Ferraro 2006, 4). Ferraro

(2006) describes pure victims as ‘meek and distraught, innocent of provoking their vic-

timization’, and as ‘[y]oung, white, middle-class, attractive (but not overtly sexy) women’

(19). The women she interviewed are much more complex. According to Ferraro

(2006), ‘the lives they speak of are not clean: they are complicated and confusing’ (7).

Through showing us the chaotic circumstances and contexts surrounding these women,

Ferraro (2006) seeks to invest women who kill or harm their abusers with the agency

denied them by the ‘language of intimate partner violence’ (13) even as she accounts for

the actions they took. Ferraro (2006) argues that offenders, even those who kill people

other than their abusers or who allow their children to be victimized, are still victims,

‘overwhelmed with demands they could not meet, afraid to challenge their partners, and

unable to escape their circumstances’ (244). By grappling with this paradox, Ferraro

broadens the parameters of what constitutes victimization, drawing in agency and allow-

ing for criminality, ‘blurring the boundaries’ in at least these two suggestive ways.

These are a few more of the ways, then, that sociologists have added new dimensions

and facets to images of victims of gender violence, showing a variety of divergences from

cultural codes and stereotypes. Loseke (1999) argues that sympathetic victims have to be

‘morally good people who are greatly harmed through no fault of their own’ (76). Femi-

nists and other kinds of scholar activists reveal some possibilities for greater inclusiveness:

women in questionable moral categories, women who have some agency, women who

themselves commit violence against others. There is more to consider, however, and we

turn now to some further complications, implications, and in our conclusion, suggestions

for how to build upon and further these new directions.

Inequality and the implications of intersectionality

In 1991, Kimberle Crenshaw, a critical race scholar, writes:

The problem with identity politics is not that it fails to transcend difference, as some critics

charge, but rather the opposite—that it frequently conflates or ignores intragroup differences. In

the context of violence against women, this elision of difference in identity politics is problem-

atic fundamentally, because the violence many women experience is often shaped by other

dimensions of their identities, such as race and class. (1242)

In this same piece, Crenshaw proposes the concept of Intersectionality as a methodological

and theoretical orientation for scholars concerned with the experiences of Black women.

Crenshaw’s (2005) work is rooted in Black Feminist thought, as well as in her experi-

ences as a survivor attempting to resist the violence in her life ‘at a time when the

boundaries of antiracism and feminism were revealing in popular culture the ways that

their narratives of oppression utterly marginalized women of color’ (312). Her ideas were

not new – but they crystallized for many the work that Black feminists had been doing

for at least the last decade. Crenshaw argues that contemporary feminist antiviolence and

antiracist rhetoric has obscured the experiences of women of color working to create lives

free of violence, and that research on violence in the lives of women must move beyond

discrete, hierarchical categories of race, class and gender to an intersectional analysis.

Similarly, Andrea Smith, a Cherokee feminist, problematizes Susan Brownmiller’s

(1975) assertion that sexual assault is ‘nothing more or less than a conscious process of

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

316 Gender and Violence

intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear’. Smith maintains this

oversimplified approach conceals the relationship between sexual violence, racism and

colonialism, and erases significant histories (and contemporary realities) in which sexual

assault is a ‘tool’ of European colonization of indigenous women and men (2005). Many

sociologists concerned with gender and violence work in theoretical tandem with women

like Crenshaw and Smith. Patricia Hill Collins posits that race, class and gender are ‘inter-

locking systems of oppression’ (1991). Addressing how Black women have had their

experiences silenced in the either ⁄ or binary implicitly created through antiracist and White

feminist narratives, Collins (2000) writes that ‘the sexual politics of Black womanhood

reveals the fallacy of assuming that gender affects all women the same way—race and class

matter greatly’ (229).

When examining gender violence, intersectional theorists argue that no oppression –

such as gender inequality – is necessarily more salient in the situation than other forms of

oppression (Crenshaw 1991); gender can be only be understood as indivisible from

race ⁄ ethnicity, class, ability, sexual orientation, and citizenship, among other statuses. As

such, when considering social phenomena like violence, an intersectional approach places

knowledge of these interrelationships at the center of inquiry (Bograd 1999).

Feminist sociologists and other scholars writing about gender violence have joined

women of color activists, advocates in the non-profit industrial complex, and academics

across the social sciences, law and the humanities to trouble popular assumptions about

the nature and amelioration of violence against women, and to critically assess the impact

of the professionalization of antiviolence agencies on women from marginalized commu-

nities. Through their work, these sociologists have tried to show that multiple, indivisible

and messy identities inform the

meaning and nature of domestic violence, how it is experienced by the self and responded to

by others, how personal and social consequences are represented, and how and whether escape

and safety can be obtained. (Bograd 1999, 276)

Importantly, sociologists and other feminist social scientists, if not outright rejecting dis-

crete social categories for an intersectional analysis, have highlighted the homogeneity of

research on violence against women. For example, Murphy et al. (2004) show that quan-

titative scales created to measure domestic violence have rarely been developed for multi-

cultural application, and qualitative explorations of domestic violence, as experienced by

women at the intersections of various inequalities, are few and far between (Bograd 1999;

Mays 2006; Sokoloff 2008). From this perspective, much of the literature which signifi-

cantly informs and is informed by the mainstream antiviolence movement in the United

States – is limited by the underrepresentation of women of color, low-income women,

rural women, LGBTQ women, women with disabilities, and non-English speakers

(Chester et al. 1994; INCITE! 2006; Nixon 2009; Waldron 1996).

Beth Richie thus argues for a ‘radical reassessment’ of the aims of activism to date. In

their efforts to impress upon the public that violence against women – a manifestation of

gender inequality – occurs across class and racial categories, the movement has created

what Richie deems the ‘everywoman’. Whether intentional or not, the faces and leader-

ship of the movement reflect ‘neutral’ priorities and strategies that best meet the needs of

middle-class, White women survivors. As Crenshaw (1991) reminds us:

intervention strategies based solely on the experiences of women who do not share the same

class or race backgrounds will be of limited help to women who because of race and class face

different obstacles. (1246)

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Gender and Violence 317

Richie also calls the movement to task for the disparity she perceives between its rhetoric

of inclusion and diversity and the persistence of primarily White leadership. Meanwhile,

many women of color continue to organize on the margins of the antiviolence and anti-

racist movements. Groups like INCITE! and Critical Resistance mobilize around new

strategies to end violence that keep the safety of survivors – particularly women of color

– at the center of concern, without further contributing to the prison-industrial complex

through the arrest and incarceration of men of color. However, there is another issue

with which to contend: the forms that organizations developed to help victims have

increasingly been forced to take.

Further complications: the professionalization of antiviolence organizations

As we note above, feminists working with the antiviolence movement have made signifi-

cant gains over the last several decades. The sizable achievements of the antiviolence

movement in the United States have come at a cost, however. As is common within other

US social movements (McCarthy and Zald 1973), the swelling of available state and phil-

anthropic resources has created a great deal of incentive for traditional grassroots, commu-

nity-based antiviolence groups to become increasingly professionalized and formalized

non-profit agencies (Adelman 2008; Bhattacharjee 2001). Staggenborg (1988) and Piven

and Cloward (1979) find this shift in organizational structure leads to the inhibition of cer-

tain strategies and tactics, and the increasing use of non-disruptive, institutionalized tactics.

The now central strategies for combating violence against women rest heavily upon law

enforcement and the criminal justice system, and scholars argue these ignore the political

priorities and personal experiences of women of color (Bhattacharjee 2001). Natalie Sokol-

off claims that early feminist objectives to generate radical social change have been lost

through continued collusion of the mainstream antiviolence movement with the state, ‘the

velvet purse of state repression’ (Rodriguez 2007, 23). An anonymous non-profit

employee of a feminist organization illustrates this succinctly: ‘Who controls the women’s

organizations in town? It’s largely the men. We still get our funding through being good

girls’ (Riger 1994, 287; see also Johnson 1981; Martin 1990; Matthews 1994).

Critics like Sokoloff contend that these new institutionalized strategies ignore how

many communities of color experience the violence of the state. In the United States, for

example, as many as one third of all young Black men are in prison, jail, on probation or

on parole (Sokoloff 2004) – with some suggesting that the prison-industrial complex has

replaced Jim Crow laws (Alexander 2010) or even recreated slavery (Brewer and Heitzeg

2008; Collins 2004; Smith and Hattery 2008). Native Americans, too, face disproportion-

ate arrest and incarceration rates, as well as significant exposure to police brutality (Smith

1999); Latinos are twice as likely to be incarcerated as Whites (Hartney 2006). Collins

(2004) argues that this prison-industrial complex, paradoxically a central strategy for fight-

ing violence against women, fosters a ‘male rape culture’ and ‘attaches a very effective

form of disciplinary control to a social institution that is rapidly becoming a new site of

slavery for Black men’ (234).

The number of women of color in US prisons has doubled in the last decade, as well

(Chesney-Lind and Pasko 2004), while the same officers responsible for aiding women

who have experienced violence are now charged with enforcing immigration law in the

post-9 ⁄ 11 era (Versanyi 2008). Sokoloff (2008) argues that for many women of color and

immigrant women, involving the police holds the potential to bring further violence onto

their bodies and into their homes and communities. How then, can current research on

and theorizing about gender violence navigate this contested terrain?

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

318 Gender and Violence

Troubling strategies and envisioning alternatives

Tensions surrounding the priorities and solutions of the antiviolence movement have

increased as the movement has gained ground. Beyond the antiviolence movement’s ties

with the state and the prison-industrial complex, many women of color activists remain

critical of another key movement strategy: helping women leave violent relationships.

Over time, this solution has been juxtaposed with staying, creating a mutually exclusive

and seemingly exhaustive dichotomy in which women survivors are either in a state of

leaving or staying. Thus, in the United States, formulae for safety measures and help for

battered women rest upon them leaving abusers.

Although this may be a viable response for middle-class White women, leaving is far

more complicated for women of color, low-income women, immigrant women,

LGBTQ women, and women with disabilities, according to some sociologists (Abraham

2000; Richie 2005; Renzetti 1996; Sokoloff 2008). Leaving abusers can mean having to

venture outside of one’s own community to seek help from service providers, hospitals,

or police located in dominant communities. Racism, heterosexism, homophobia, anti-

immigrant sentiment, ableism, language barriers, immigration status concerns, and fear of

the police may potentially intersect – rendering the act of leaving fraught with danger

and fear (Abraham 2000; Erez et al. 2009; Mays 2006; Sokoloff 2008; Waldron 1996).

Additionally, women leaving their racial ⁄ ethnic communities or their LGBTQ communi-

ties to seek help may feel tremendous pressure from others not to air the community’s

‘dirty laundry’ to dominant society. Sharing experiences of intimate partner violence with

an outside community leaves those experiences vulnerable to being used to further inform

narratives about and oppression towards the communities in which the survivor is a

member (De Vidas 2000; Kanuha 1990; Waldron 1996).

Sokoloff claims that this forced choice between leaving and staying inhibits or obscures

self-determined and creative alternatives that better meet the needs of women seeking

freedom from violence, as they navigate multiple oppressions and violence not only in

their own communities but in dominant society as well. Margaret Abraham (2000)

writes:

…when we assume there is one overarching problem and one way to address it, we limit both

our vision and our ability to individually and collectively contribute to the struggle to end

domestic violence. (xi)

Heeding Crenshaw’s (2005, 312) call for ‘mapping, context by context, what difference

our difference [makes]’ (312), feminists sociologists have advocated for services that truly

reflect an understanding of how marginalized identities intersect with the experiences of

domestic violence. For example, activists and writers specifically considering the needs of

immigrant women have increasingly called for multiple language interpreters, as well as

staff with a working knowledge of state and federal immigration laws (Erez et al. 2009).

Through their research, intersectional scholars have highlighted how contact with state

agencies can become problematic for undocumented women, women fearful of jeopar-

dizing their immigration status, and women from communities that have experienced

state violence and ⁄ or communities with mixed immigration statuses (Bograd 1999; Bui

2003; Dasgupta 2005; Perilla et al. 1994; Sokoloff 2008).

Others, like Byron Johnson and sociologist Neil Websdale, contend that structural

interventions are needed that offer women material resources like independent housing,

childcare, education and other services. These ‘preventative’ tactics are multi-faceted

and remove the criminal justice system as the primary response to domestic violence

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Gender and Violence 319

(Websdale and Johnson 2005). Andrea Smith challenges advocates to organize beyond

merely building anti-violence programs and to think about fighting broader social struc-

tures that support violence against women. She writes that women will be better served

by being seen as organizers or potential organizers, rather than as clients. Finally, Smith

calls for activists, advocates, and academics to develop strategies that speak to both state

and interpersonal violence (2008).

In sum, many scholars within and outside the discipline of sociology argue that, racism,

homophobia, anti-immigrant sentiment, colonialism, and ableism are intersecting oppres-

sions that significantly complicate how women experience intimate partner violence and

the strategies they use to create lives free from violence. The activism of and intersection-

al scholarship focusing upon women at the margins of the antiviolence movement contin-

ues to challenge mainstream definitions, strategies, and rhetoric. Through these processes,

images of victims of gender violence become significantly more diverse and analyses of

their experience simultaneously broader and more focused.

Concluding considerations

As we have documented scholarly, and activist understandings of violence against

women have seen enormous shifts across the last four decades, yet continue to resonate

and reverberate in an uneasy cultural terrain. Beginning in the 1970s, many feminist

sociologists worked to explain gender violence as a function of patriarchal social struc-

tures, and as a means of the social control of women and children. Activists and scholars

alike contested dominant cultural beliefs that women were partly or wholly responsible

for the intimate violence they experienced. Radically different from patriarchal explana-

tions at the time, antiviolence advocates posited that women were never to blame for

the violence they experienced. From such explanations, typifications emerged which

inadvertently threatened to strip women victims of agency, a problem quickly recognized

by the same activists and scholars constructing gender violence victimization. We believe

that and have tried to show how these concerns lead logically to the illumination of fur-

ther deviations; scholarship contending that the narratives emerging from the antivio-

lence movement fail to adequately represent the messy, complex and diverse experiences

of everyday victims and victimization. Finally, we addressed the growing number of

scholars and activists who have demanded that discussions of gender violence include

multiple dimensions of inequality and their intersections. This trend may be influenced

in part by our growing sociological interests in intersectionality in general, but at the

same time, begins with and springs from the groundwork laid by earlier discourses of

victimization. Our hope is that scholarship on gender violence continues this trending

towards ever more nuanced and complex conceptualizations of violence and victims, that

explores further the myriad expressions of resistance and strategic compliance in which

victims and survivors engage, and that attends to the subtleties as well as the extremes of

victimization, the ambiguities as well as the obvious, and oppressions above and beyond

gender inequality.

Short Biographies

S.J. Creek’s research focuses on the intersections of gender, sexuality, and religion in

social movements. Recently, her co-authored paper on race, religiosity and attitudes

about same-sex marriage was published in Social Science Quarterly. She is a doctoral

candidate at Southern Illinois University Carbondale and is currently working on her

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

320 Gender and Violence

dissertation – a consideration of the lived experiences of participants in the ex-gay

movement in the United States.

Jennifer L. Dunn’s research has examined the social construction of victims in multiple

realms; she has published work on stalking victims’ identity work and experience of being

victim-witnesses in the criminal justice system, emerging vocabularies of motive in the

battered women’s movement, and the emotional and political resonance of social move-

ments’ framing of victims. Her work appears in the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography,

Social Problems, Symbolic Interaction, Sociological Inquiry, Sociological Focus, and Violence Against

Women. Her book, Courting Disaster: Intimate Stalking, Culture, and Criminal Justice, won

the Charles Horton Cooley Award of the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction,

and she recently was awarded an Early Career Scholarship Award from the Midwest

Sociological Society. She earned her BA in Sociology at Sonoma State University and

her MA and PhD in Sociology from the University of California at Davis. Her most

recent book, Judging Victims Why We Stigmatize Survivors, and How They Reclaim Respect,

examines victim narratives in survivors’ movements in contemporary United States.

Note

* Correspondence address: S.J. Creek, Department of Sociology, Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Faner

Hall Mailcode 4524, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA. E-mail: creek.s.j@gmail.com

References

Abraham, M. 2000. Speaking the Unspeakable: Marital Violence Among South Asians in the US New Brunswick. New

Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Adelman, M. 2008. ‘The ‘‘Culture’’ of the Global Anti–Gender Violence Social Movement.’ American Anthropologist

110: 511–4.

Alexander, Michelle. 2010. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New

Press.

Amir, Menachem. 1971. Patterns in Forcible Rape. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Barry, Kathleen. 1979. Female Sexual Slavery. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Best, Joel. 1995. ‘Typification and Social Problems Construction.’ Pp. 3–10 in Images of Issues: Typifying Contempo-

rary Social Problems, edited by Joel Best. New York: Aldine.

Bhattacharjee A. 2001. ‘Whose Safety? Women of Color and the Violence of Law Enforcement.’ Report for Justice

Vision: American Friends Service Committee-Committee on Women, Population and the Environment, Philadelphia, PA.

Bograd, Michele. 1999. ‘Strengthening Domestic Violence Theories: Intersections Of Race, Class, Sexual Orienta-

tion, and Gender.’ Journal of Marital & Family Therapy 25: 275–89.

Brewer, R. M. and N. A. Heitzeg. 2008. ‘The Racialization of Crime and Punishment: Criminal Justice, Color-Blind

Racism, and the Political Economy of the Prison Industrial Complex.’ American Behavioral Scientist 51: 625.

Brownmiller, Susan. 1975. Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape. New York: Bantam.

Bui, Hoan N. 2003. ‘Help-Seeking Behavior Among Abused Immigrant Women.’ Violence Against Women 9: 207.

Chesney-Lind, M. and L. Pasko. 2004. The Female Offender: Girls, Women, and Crime. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications, Inc.

Chester, B., R. W Robin, M. P Koss, J. Lopez and D. Goldman. 1994. ‘Grandmother Dishonored: Violence

Against Women by Male Partners in American Indian Communities.’ Violence and Victims 9: 249–58.

Clark, Candace. 1997. Misery and Company: Sympathy in Everyday Life. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Collins, P. H. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York:

Routledge.

Collins, P. H. 2004. Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the new Racism. New York: Theatre Arts Books.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. ‘Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women

of Color.’ Stanford Law Review 43: 1241–99.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. 2005. ‘Reflection.’ Pp. 312–4 in Violence Against Women: Classic Papers, edited by Raquel L.

Kennedy Bergen, Jeffrey L. Edleson and Claire M. Renzetti. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Dasgupta, Shamita Das. 2005. ‘Women’s Realities: Defining Violence Against Women by Immigration, Race, and

Class.’ Pp. 56–70 in Domestic Violence At The Margins: Readings on Race, Class, Gender, And Culture, edited by

Natalie J. Sokoloff and Christina Pratt. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University.

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Gender and Violence 321

Davies, J. M., E. Lyon and D. Monti-Catania. 1998. Safety Planning With Battered Women: Complex Lives ⁄ Difficult

Choices. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

De Vidas, M. 2000. ‘Childhood Sexual Abuse and Domestic Violence.’ Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 10:

51–68.

Dobash, R. E. and R. Dobash. 1979. Violence Against Wives: A Case Against the Patriarchy. New York: Free Press.

Dunn, Jennifer L. 2004. ‘The Politics of Empathy: Social Movements and Victim Repertoires.’ Sociological Focus

37(3): 235–50.

Dunn, Jennifer L. 2005. ‘‘Victims’ and ‘Survivors’: Emerging Vocabularies of Motive for ‘Battered Women Who

Stay.’ Sociological Inquiry 75(1): 1–30.

Dunn, Jennifer L. 2010. ‘Vocabularies of Victimization: Toward Explaining the Deviant Victim.’ Deviant Behavior

31: 159–83.

Dunn, Jennifer and Melissa Powell-Williams. 2007. ‘‘Everybody Makes Choices’: Victim Advocates and the Social

Construction of Battered Women’s Victimization and Agency.’ Violence Against Women 13: 10.

Erez, E., M. Adelman and C. Gregory. 2009. ‘Intersections of Immigration and Domestic Violence: Voices of

Battered Immigrant Women.’ Feminist Criminology 4: 32.

Ferraro, K. J. 2006. Neither Angels Nor Demons: Women, Crime, and Victimization. Boston, MA: Northeastern

University Press.

Gondolf, Edward W. (with Ellen R. Fisher). 1988. Battered Women as Survivors: An Alternative to Treating Learned

Helplessness. Toronto: D.C. Health.

Griffin, Susan. 1971. ‘Rape: The All-American Crime.’ Ramparts 10: 26–35.

Hartney, Chris. 2006. ‘US Rates of Incarceration: A Global Perspective.’ Report for The National Council on Crime

and Delinquency. Washington, DC.

Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1979. ‘Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.’ American Journal of Sociology

85: 551–75.

Hoff, Lee Ann. 1990. Battered Women as Survivors. New York: Routledge.

Holstein, James A. and Gale Miller. 1990. ‘Rethinking Victimization: An Interactional Approach to Victimology.’

Symbolic Interaction 13(1): 103–22.

INCITE! Women of Color Against Violence. 2009. The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Indus-

trial Complex. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

Jenkins, Pamela J. 1996. ‘Contested Knowledge: Battered Women as Agents and Victims.’ Pp. 93–111 in Witnessing

for Sociology: Sociologists in Court, edited by Pamela J. Jenkins and Steve Kroll-Smith. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Johnson, John M. 1981. ‘Program Enterprise and Official Cooptation in the Battered Women’s Shelter Movement.’

American Behavioral Scientist 24(6): 827–42.

Kanuha, V. 1990. ‘Compounding the Triple Jeopardy.’ Women & Therapy 9: 169–84.

Kelly, Liz. 1988. Surviving Sexual Violence. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Lamb, Sharon. 1999. ‘Constructing the Victim: Popular Images and Lasting Labels.’ Pp. 108–38 in New Versions

of Victims: Feminists Struggle With the Concept, edited by Sharon Lamb. New York: New York University

Press.

Leisenring, Amy. 2006. ‘Confronting ‘Victim’ Discourses: The Identity Work of Battered Women.’ Symbolic Interac-

tion 29(3): 307–30.

Loseke, Donileen R. 1989. ‘‘Violence’ is ‘Violence’... or is it? The Social Construction of ‘Wife Abuse’ and Public

Policy.’ Pp. 191–206 in Images of Issues: Typifying Contemporary Social Problems, edited by Joel Best. New York:

Aldine de Gruyter.

Loseke, Donileen R. 1992. The Battered Woman and Shelters: The Social Construction of Wife Abuse. New York: State

University of New York Press.

Loseke, Donileen R. 1999. Thinking About Social Problems: An Introduction to Constructionist Perspectives. New York:

Aldine de Gruyter.

Loseke, Donileen R. 2001. ‘Lived Realities and Formula Stories of ‘Battered Women’.’ Pp. 107–26 in Institutional

Selves: Troubled Identities in Postmodern World, edited by Jaber F. Gubrium and James A. Holstein. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Martin, Patricia Yancey. 1990. ‘Rethinking Feminist Organizations.’ Gender and Society 4(2): 182–206.

Matthews, N. A. 1994. Confronting Rape: The Feminist Anti-Rape Movement and The State. New York: Routledge.

Mays, Jennifer M. 2006. ‘Feminist Disability Theory: Domestic Violence Against Women With a Disability.’

Disability & Society 21: 147.

McCarthy, John D. and Mayer N. Zald. 1973. The Trend of Social Movements in America: Professionalization and

Resource Mobilization. Morristown, NJ: General Learning Press.

Murphy, S. B., C. Risley-Curtiss and K. Gerdes. 2004. ‘American Indian Women and Domestic Violence.’ Journal

of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 7: 159–81.

Nixon, Jennifer. 2009. ‘Domestic Violence and Women With Disabilities: Locating the Issue on the Periphery of

Social Movements.’ Disability & Society 24: 77–89.

Pagelow, M. D. 1981. Woman-Battering: Victims and Their Experiences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

322 Gender and Violence

Perilla, Julia, Roger Bakeman and Fran Norris. 1994. ‘Culture and Domestic Violence: The Ecology of Abused

Lesbians.’ Violence and Victims 9: 4.

Picart, Caroline Joan (Kay) S. 2003. ‘Rhetorically Reconfiguring Victimhood and Agency: The Violence Against

Women Act’s Civil Rights Clause.’ Rhetoric and Public Affairs 6(1): 97–126.

Piven, Frances Fox and Richard A. Cloward. 1979. Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed. How They Fail,

NY: Vintage Books.

Plummer, Kenneth. 1995. Telling Sexual Stories: Power, Change, and Social Worlds. New York: Routledge.

Renzetti, Claire. 1996. ‘The Poverty of Services for Battered Lesbians.’ Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 4: 61.

Richie, Beth E. 2005. ‘A Black Feminist Reflection on the Antiviolence Movement.’ Pp. 50–5 in Domestic Violence

at The Margins: Readings on Race, Class, Gender, and Culture, edited by Natalie J. Sokoloff and Christina Pratt.

New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Riger, S. 1994. ‘Challenges of Success: Stages of Growth in Feminist Organizations.’ Feminist Studies 20: 275–300.

Rodriguez, D. 2007. ‘The Political Logic of The Non-Profit Industrial Complex.’ Pp. 21–40 in This Revolution

Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non Profit Industrial Complex, edited by INCITE!. Brooklyn. New York: South

End Press

Russell, Diana E. H. 1975. The Politics of Rape: The Victim’s Perspective. New York: Stein and Day.

Smith, Andrea. 1999. ‘Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide.’ Journal of Religion & Abuse 1: 31.

Smith, E. and A. Hattery. 2008. ‘The Globalization of the US Prison-Industrial Complex.’ Pp. 247–66 in Globaliza-

tion and America: Race, Human Rights, and Inequality, edited by Angela Hattery, David Embrick and Earl Smith.

Latham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Sokoloff, Natalie J. 2004. ‘Domestic Violence at the Crossroads: Violence Against Poor Women and Women of

Color.’ Women.’ s Studies Quarterly 32: 139–47.

Sokoloff, Natalie J. 2008. ‘The Intersectional Paradigm and Alternative Visions to Stopping Domestic Violence:

What Poor Women, Women of Color, and Immigrant Women are Teaching Us About Violence in the Family.’

International Journal of Sociology of the Family 34: 153–85.

Staggenborg, S. 1988. ‘The Consequences of Professionalization and Formalization in The Pro-Choice Movement.’

American Sociological Review 53: 585–605.

Straus, Murray A. 1992. ‘Sociological Research and Social Policy: The Case of Family Violence.’ Sociological Forum

7(2): 211–37.

Varsanyi, Monica. 2008. ‘Should Cops Be La Migra?’ Los Angeles Times, April 20. http://articles.latimes.com/2008/

apr/20/opinion/op-varsanyi20 (Last accessed February 2, 2011).

Waldron, Charlene M. 1996. ‘Lesbians of Color and the Domestic Violence Movement.’ Journal of Gay & Lesbian

Social Services 4: 43.

Websdale, N. and B. Johnson. 2005. ‘Reducing Woman Battering: The Role of Structural Approaches.’

Pp. 389–415 in Domestic Violence at the Margins: Readings on Race, Class, Gender, and Culture, edited by Natalie

Sokoloff. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Weis, Kurt and Sandra Borges. 1973. ‘Victimology and Rape: The Case of the Legitimate Victim.’ Issues in Criminology

8: 71–115.

ª 2011 The Authors Sociology Compass 5/5 (2011): 311–322, 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00360.x

Sociology Compass ª 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Holy Rosary 2Dokument14 SeitenThe Holy Rosary 2Carmilita Mi AmoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Study in USADokument4 SeitenWhy Study in USALowlyLutfurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microplastic Occurrence Along The Beach Coast Sediments of Tubajon Laguindingan, Misamis Oriental, PhilippinesDokument13 SeitenMicroplastic Occurrence Along The Beach Coast Sediments of Tubajon Laguindingan, Misamis Oriental, PhilippinesRowena LupacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Laws (MOHD AQIB SF)Dokument18 SeitenLand Laws (MOHD AQIB SF)Mohd AqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- 09 Task Performance 1-ARG - ZABALA GROUPDokument6 Seiten09 Task Performance 1-ARG - ZABALA GROUPKylle Justin ZabalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cases in Political Law Review (2nd Batch)Dokument1 SeiteCases in Political Law Review (2nd Batch)Michael Angelo LabradorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Dokument2 SeitenDewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Dewi Handariatul MahmudahNoch keine Bewertungen

- WHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EngDokument12 SeitenWHO in The Philippines-Brochure-EnghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidDokument17 SeitenAlkyl Benzene Sulphonic AcidZiauddeen Noor100% (1)

- Descartes and The JesuitsDokument5 SeitenDescartes and The JesuitsJuan Pablo Roldán0% (3)

- Barrier Solution: SituationDokument2 SeitenBarrier Solution: SituationIrish DionisioNoch keine Bewertungen

- PRCSSPBuyer Can't See Catalog Items While Clicking On Add From Catalog On PO Line (Doc ID 2544576.1 PDFDokument2 SeitenPRCSSPBuyer Can't See Catalog Items While Clicking On Add From Catalog On PO Line (Doc ID 2544576.1 PDFRady KotbNoch keine Bewertungen

- DIS Investment ReportDokument1 SeiteDIS Investment ReportHyperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dessert Banana Cream Pie RecipeDokument2 SeitenDessert Banana Cream Pie RecipeimbuziliroNoch keine Bewertungen

- S0260210512000459a - CamilieriDokument22 SeitenS0260210512000459a - CamilieriDanielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role and Responsibilities of Forensic Specialists in Investigating The Missing PersonDokument5 SeitenRole and Responsibilities of Forensic Specialists in Investigating The Missing PersonMOHIT MUKULNoch keine Bewertungen

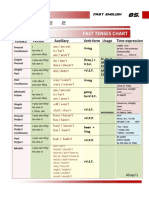

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDokument5 SeitenTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morals and Dogma of The Ineffable DegreesDokument134 SeitenMorals and Dogma of The Ineffable DegreesCelephaïs Press / Unspeakable Press (Leng)86% (7)

- Implementation of Brigada EskwelaDokument9 SeitenImplementation of Brigada EskwelaJerel John Calanao90% (10)

- NEC Test 6Dokument4 SeitenNEC Test 6phamphucan56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Memorandum of Inderstanding Ups and GoldcoastDokument3 SeitenMemorandum of Inderstanding Ups and Goldcoastred_21Noch keine Bewertungen

- 13th Format SEX Format-1-1: Share This DocumentDokument1 Seite13th Format SEX Format-1-1: Share This DocumentDove LogahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Persephone and The PomegranateDokument3 SeitenPersephone and The PomegranateLíviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project Initiation & Pre-StudyDokument36 SeitenProject Initiation & Pre-StudyTuấn Nam NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lunacy in The 19th Century PDFDokument10 SeitenLunacy in The 19th Century PDFLuo JunyangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Retail Strategy: MarketingDokument14 SeitenRetail Strategy: MarketingANVESHI SHARMANoch keine Bewertungen

- ChinduDokument1 SeiteChinduraghavbiduru167% (3)

- Unit 2 Organisational CultureDokument28 SeitenUnit 2 Organisational CultureJesica MaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Advert For The Blue Economy PostsDokument5 SeitenFinal Advert For The Blue Economy PostsKhan SefNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nestle Corporate Social Responsibility in Latin AmericaDokument68 SeitenNestle Corporate Social Responsibility in Latin AmericaLilly SivapirakhasamNoch keine Bewertungen