Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Business Policy and Strategic MGT Block - 1

Hochgeladen von

abdikarimOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Business Policy and Strategic MGT Block - 1

Hochgeladen von

abdikarimCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

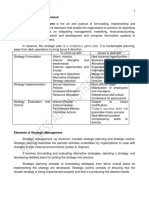

Business Policy & Strategic Management 7

Unit-I : Introduction to Strategic Management Notes

Structure

1.1 Concept of Strategic Management

1.2 What is a Strategy?

1.2.1 Features of Strategy

1.3 Strategic Management-History and Development

1.4 Basic Financial Planning (Budgeting)

1.5 Long-range Planning (Extrapolation)

1.6 Strategic (Externally Oriented) Planning

1.7 Strategic Planning to Strategic Management

1.8 Complex System Strategy

1.8.1 Emergence

1.8.2 Chaos & Complexity

1.8.3 System Thinking

1.8.4 Darwinian Theory

1.9 Complex Dynamic System

1.9.1 Hybrid Systems

1.9.2 Predictive Modeling

Objective

• To study the evolution of strategic management and understand the basics of

strategy and strategic management

• To understand the history of strategic management

• To analyze how strategic management plays an important role in the growth of

an organization

• To understand the various aspects of strategic planning to strategic

management

“Study of the functions and responsibilities of general managers; of problems

that affect the success of the total organization and the decisions that determine the

direction of the organization and shape its future”

Chance favors the prepared mind -- Louis Pasteur

1.1 Concept of Strategic Management

Strategic Management is all about identification and description of the strategies

that managers can carry so as to achieve better performance and a competitive

advantage for their organization. An organization is said to have competitive advantage

if its profitability is higher than the average profitability for all companies in its industry.

Strategic management is the process of managing the pursuit of organizational

mission while managing the relationship of the organization to its environment

--James M. Higgins

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

8 Business Policy & Strategic Management

Strategic management is defined as the set of decisions and actions resulting in the

Notes formulation and implementation of strategies designed to achieve the objectives of the

organization

(John A. Pearce II and Richard B. Robinson, Jr.)

Strategic management can also be defined as a bundle of decisions and acts which

a manager undertakes and that decide the firm’s performance. The manager must

have a thorough knowledge and analysis of the general and competitive organizational

environment so as to take right decisions. They should conduct a SWOT Analysis

(Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats), i.e., they should make best

possible utilization of strengths, minimize the organizational weaknesses, make

use of arising opportunities from the business environment and shouldn’t ignore the

threats. Strategic management is nothing but planning for both predictable as well as

unforeseen contingencies. It is applicable to both small as well as large organizations

as even the smallest organization face competition. By formulating & implementing

appropriate strategies, they can attain sustainable competitive advantage.

Strategic Management is a way in which strategists set the objectives and proceed

about attaining them. It deals with making and implementing decisions about future

direction of an organization. It helps us to identify the direction in which an organization

is moving.

Strategic management is a continuous process that evaluates and controls

the business and the industries in which an organization is involved; evaluates its

competitors and sets goals and strategies to meet all existing and potential competitors;

and then reevaluates strategies on a regular basis to determine how it has been

implemented and whether it was successful or does it needs any modification.

Strategic Management gives a broader perspective to the employees of an

organization and they can better understand how their job fits into the entire

organizational plan and how it is co-related to other organizational members. It is

nothing but the art of managing employees in a manner which maximizes the ability

of achieving business objectives. The employees become more trustworthy, more

committed and more satisfied as they can co-relate themselves with each organizational

task. They can understand the reaction of environmental changes on the organization

and the probable response of the organization with the help of strategic management.

Employees can judge the impact of such changes on their own job and can effectively

face the changes. Managers & employees need to be both effective as well as efficient.

We can therefore say that Strategic Management helps to--

• Develop “theme” for organization

• Provide discipline for long-term thinking

• Deal with environmental complexities

• More effective resource allocation

• Integrate diverse administrative activities

• Increase managerial effectiveness

• Improve employee motivation

• Address stakeholder concerns

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 9

One of the major roles of strategic management is to incorporate various functional

areas of the organization and to ensure that these functional areas harmonize and get Notes

together well. Another role of strategic management is to keep an eye on the goals and

objectives of the organization.

1.2 What is a Strategy?

“Strategy can be defined as knowledge of the goals and the uncertainty of unfolding

of events”

The word “strategy” is derived from the Greek word “strategeos”; stratus (meaning

army) and “ago” (meaning leading/moving).

Strategy is an action that managers take to attain one or more of the organization’s

goals. Strategy can also be defined as “A general direction set for the company and its

various components to achieve a desired state in the future. Strategy results from the

detailed strategic planning process”.

A strategy is all about integrating organizational activities and utilizing and allocating

the scarce resources within the organizational environment so as to meet the current

objectives. While planning a strategy it is essential to consider that decisions are not

taken in a vaccum and that any action taken by a firm is likely to be met by a reaction

from those affected i.e. competitors, customers, employees or suppliers.

Henry Mintzberg, in his 1994 book, “The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning “, points

out that people use “strategy” in several different ways, the most significant are--:

• Strategy is a plan, a “how,” a means of getting from here to there.

• Strategy is a pattern in actions over time; for example, a company that

regularly markets very expensive products is using a “high end” strategy.

• Strategy is position; that is, it reflects decisions to offer particular products or

services in particular markets.

• Strategy is perspective, that is, vision and direction.

Strategy needs to take into consideration the likely or actual behavior of others.

Strategy is the blueprint of decisions in an organization that shows its objectives

and goals, reduces the key policies, and plans for achieving these goals. It defines

the business the companies intend to carry on, the type of economic and human

organization they want to be, and the contribution they plan to make to its shareholders,

customers and society at large.

• Means of establishing organizational purpose

• Definition of the competitive domain

• Response to external opportunities and threats and internal strengths and

weaknesses

• Way to define managerial tasks with corporate, business and functional

perspectives

• Coherent, unifying and integrative pattern of decisions

• Definition of the economic and non-economic contribution the firm intends to

make to stakeholders

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

10 Business Policy & Strategic Management

• Expression of strategic intent

Notes

• Means to develop organizational core competencies to create sustainable

competitive advantage

1.2.1 Features of Strategy

1. Strategy is Significant because it is not possible to foresee the future. Without a

perfect foresight, the firms must be ready to deal with the uncertain events which

constitute the business environment.

2. Strategy deals with long term developments rather than routine operations, i.e. it

deals with probability of innovations or new products, new methods of productions,

or new markets to be developed in future.

3. Strategy is created to take into account the probable behavior of customers and

competitors. Strategies dealing with employees will predict the employee behavior.

Strategy is a well defined roadmap of an organization. It defines the overall mission,

vision and direction of an organization. The objective of a strategy is to maximize an

organization’s strengths and to minimize the strengths of the competitors. Strategy, in

short, bridges the gap between “where we are” and “where we want to be”.

1.3 Strategic Management-History and Development

Until the 1940s, strategy was seen as primarily a matter for the military. Military

history is replete with stories about strategy. Almost from the beginning of recorded

time, leaders contemplating battle have devised offensive and counter-offensive

moves to defeat the enemy. The word strategy derives from the Greek for generalship,

strategia, and entered the English vocabulary in 1688 as ‘strategie’. According to

James’ 1810 Military Dictionary, it differs from tactics, which are immediate measures

in face of an enemy. Strategy concerns something “done out of sight of an enemy.” Its

origin dates back to Sun Tzu’s The Art of War of 500 BC.

Over the years, the practice of strategy has evolved through five phases (each

phase generally involved the perceived failure of the previous phase):

1. Basic Financial Planning (Budgeting)

2. Long-range Planning (Extrapolation)

3. Strategic (Externally Oriented) Planning

4. Strategic Management

5. Complex Systems Strategy:

• Complex Static Systems or Emergence

• Complex Dynamic Systems or Strategic Balance

1.4 Basic Financial Planning (Budgeting)

James McKinsey (1889-1937), founder of the global management consultancy that

bears his name, was a professor of cost accounting at the school of business at the

University of Chicago. His most important publication, Budgetary Control (1922), is

quoted as the start of the era of modern budgetary accounting.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 11

Early efforts in corporate strategy were generally limited to the development of a

budget, with managers realizing that there was a need to plan the allocation of funds. Notes

Later, in the first half of the 1900s, business managers expanded the budgeting process

into the future. Budgeting and strategic changes (such as entering a new market)

were synthesized into the extended budgeting process, so that the budget supported

the strategic objectives of the firm. With the exception of the Great Depression, the

competitive environment at this time was fairly stable and predictable.

1.5 Long-range Planning (Extrapolation)

Long-range Planning was simply an extension of one year financial planning into

five-year budgets and detailed operating plans. It involved little or no consideration of

social or political factors, assuming that markets would be relatively stable. Gradually, it

developed to encompass issues of growth and diversification.

In the 1960s, George Steiner did much to focus business manager’s attention on

strategic planning, bringing the issue of long-range planning to the forefront. Managerial

Long-Range Planning, edited by Steiner focused upon the issue of corporate long-

range planning. He gathered information about how different companies were

using long-range plans in order to allocate resources and to plan for growth and

diversification.

A number of other linear approaches also developed in the same time period,

including “game theory”. Another development was “operations research”, an approach

that focused upon the manipulation of models containing multiple variables. Both have

made a contribution to the field of strategy.

1.6 Strategic (Externally Oriented) Planning

Strategic (Externally Oriented) Planning aimed to ensure that managers engaged

in debate about strategic options before the budget was drawn up. Here the focus of

strategy was on the business units (business strategy) rather than in the organization

centre. The concept of business strategy started out as ‘business policy’, a term still

in widespread use at business schools today. The word policy implies a ‘hands-off’,

administrative, even intellectual approach rather than the implementation-focused

approach that characterizes much of modern thinking on strategy. In the mid-1900s,

business managers realized that external events were playing an increasingly important

role in determining corporate performance. As a result, they began to look externally

for significant drivers, such as economic forces, so that they could try to plan for

discontinuities. This approach continued to find favor well into the 1970s.

While the theorists were arguing, one large US Company was quietly innovating.

General Electric Co. (GE) had begun to develop the concept of strategic business

units (SBUs) in the 1950s. The basic idea-now largely accepted as the normal and

obvious way of going about things-was that strategy should be set within the context of

individual businesses which had clearly defined products and markets. Each of these

businesses would be responsible for its own profits and development, under general

guidance from headquarters.

The evolution of strategy began in the early 1960s, when a flurry of authoritative

texts suddenly turned strategic planning from an issue of vague academic interest into

an important concern for practicing managers. Prior to this strategy wasn’t part of the

normal executive vocabulary.

Alfred Chandler (1918-2007), Influential figure in both strategy and business

structure-Strauss Professor of Business History at Harvard since 1971.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

12 Business Policy & Strategic Management

Chandler talks about the development of the management of a large company from

Notes history; in particular from the mid nineteenth century to the end of the First World War

(what he calls ‘the formative years of modern capitalism’). During this period, the typical

entrepreneurial or family firm gave way to larger organizations containing multiple units.

A new form of management was needed because the owner-manager could not be

everywhere at once. In addition, a new breed of manager was needed to operate in this

environment – the salaried professional.

He advised splitting the functions of strategic thinking and line management. In

Chandler’s analysis, the effective organization now separates strategy and day-to-day

operations. Strategy becomes the responsibility of managers at headquarters, leaving

the unit managers to concentrate on the here and now in decentralized units. In effect,

he was advising creating a line management who would carry out plans developed by a

more serious staff function elsewhere.

His influential book Strategy and Structure was published in 1962, appealing to

many large companies that were having difficulty in coping with their size. In recent

years it has come under heavy attack from critics, who maintain that strategy must be a

line responsibility, decided as close as possible

John Gardner’s Self-Renewal, published in 1964, which pointed out that

organizations constantly need to reassess themselves, had the earliest real impact

on managers. Like people, they need to keep renewing their skills and abilities –

something they can only do effectively through careful planning.

Kirby Warren at Harvard looked in depth at what happened in a small number of

companies to see what worked well and what didn’t. In several companies for example,

he found that the managers confused the strategic plan with its components – in

particular, the marketing plan was often assumed to be the same thing as the overall

corporate plan.

Wickham Skinner (1924-) who was based at Harvard since 1960, pointed out that

an excessive focus on marketing Planning frequently led companies to forget about

manufacturing needs until late in the day, when there was little room for manoeuvre.

Skinner argued for a clear manufacturing strategy to proceed in parallel with the

marketing strategy. In many ways he was ahead of his time, for the concept of

technology strategy or manufacturing strategy had only begun to take root in the 1980s

and many manufacturing companies still have no one in charge of this aspect of their

business.

One particularly influential idea from skinner was the ‘focused factory’. He

demonstrated that it was not normally possible for a production unit to focus on more

than one style of manufacturing. Even if the same machines were used to produce

basically similar products, if those products had very different customer demands

that required a different manner of working, the factory would not be successful. For

example, trying to produce equipment for the consumer market, where a certain error

rate in production was compensated for by higher volume sales at a lower price, was

incompatible with producing 100 per cent perfect product for the military. The most likely

outcome was a compromise that satisfies no one.

Paul Lawrence and Jay Lorsch, also from Harvard, put forth their contingency

theory of organizations. They argued that every organization is composed of multiple

paradoxes. On the one hand, each department or unit has its own objectives and

environment. It responds to those in its own way, both in terms of how it is structured,

the time horizons people assume, the formality or informality of how it goes about its

tasks and so on. All these factors contribute towards what they call ‘differentiation’. At

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 13

the same time each unit needs to work with others in pursuit of common goals. That

requires a certain amount of ‘integration’, to ensure that they are all working with rather Notes

than against each other. In their studies of US firms in a variety of manufacturing

industries, they found that companies with a high level of differentiation could also

have a high level of integration. The reason was simple; the greater the differentiation,

the more potential for conflict between departments and therefore the greater the

need for mechanisms to help them work together. Their work forced many managers

to understand that organizations were not fixed; that strategy and planning had to be

adapted to each segment of the environment with which they dealt.

Igor Ansoff (1918-2002) through his unstintingly serious, analytical and complex,

Corporate Strategy, published in 1965, had a highly significant impact on the business

world. It propelled consideration of strategy into a new dimension. It was Ansoff who

introduced the term strategic management into the business vocabulary.

Ansoff’s sub-title was “An Analytical Approach to Business Policy for Growth

and Expansion. “ The end product of strategic decisions is deceptively simple; a

combination of products and markets is selected for the firm. This combination is

arrived at by addition of new product-markets, divestment from some old ones, and

expansion of the present position,” writes Ansoff. While the end product was simple,

the processes and decisions which led to the result produced a labyrinth followed only

by the most dedicated of managers. Analysis – and in particular ‘gap analysis’ (the gap

between where Organization are now and where Organization want to be) – was the

key to unlocking strategy.

The book also brought the concept of ‘synergy’ to a wide audience for the first time.

In Ansoff’s original creation it was simply summed up as the “2+2=5” effect. In his

later books, Ansoff refined his definition of synergy to any “effect which can produce a

combined return on the firm’s resources greater than the sum of its parts.”

While Corporate Strategy was a notable book for its time, it produced what Ansoff

himself labeled “paralysis by analysis”; repeatedly making strategic plans which

remained unimplemented.

Reinforced by his conviction that strategy was a valid, if incomplete concept, Ansoff

followed up Corporate Strategy with Strategic Management (1979) and Implanting

Strategic Management (1984). His other books include Business Strategy (1969),

Acquisition Behavior in the US Manufacturing Industry, 1948-1965 (1971), From

Strategic Planning to Strategic Management (1974), and The New Corporate Strategy

(1988).

Implanting Strategic Management, co-written with Edward McDonnell, records

much of the research conducted by Ansoff and his associates and reveals a number of

ingenious aspects of the Ansoff model. These include his approach to using incremental

implementation for managing resistance to change, product portfolio analysis, and issue

related to management systems.

The Problem with Strategic Planning (Analysis): The fuel for the modern growth

in interest in all things strategic has been analysis. While analysis has been the

watchword, data has been the password. Managers have assumed that anything

which could not be analyzed could not be managed. The belief in analysis is part of a

search for a logical commercial regime, a system of management which will, under any

circumstances, produce a successful result. Indeed, all the analysis in the world can

lead to decisions which are plainly wrong. IBM had all the data about its markets, yet

reached the wrong conclusions.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

14 Business Policy & Strategic Management

There are two basic problems with the reliance on analysis. First, it is all technique.

Notes The second problem is more fundamental. Analysis produces a self-increasing loop.

The belief is that more and more analysis will bring safer and safer decisions. The

traditional view is that strategy is concerned with making predictions based on analysis.

Predictions, and the analysis which forms them, lead to security. The bottom line is not

expansion, future growth or increased profitability-it is survival. The assumption is that

growth and increased profits will naturally follow. If, by using strategy, we can increase

our chances of predicting successful methods, then our successful methods will lead us

to survival and perhaps even improvement. So, strategy is to do with getting it right or,

as the more competitive would say, winning. Of course it is possible to win battles and

lose wars and so strategy has also grown up in the context of linking together a series

of actions with some longer-term goals or aims.

This was all very well in the 1960s and for much of the 1970s. Predictions and

strategies were formed with confidence and optimism (though they were not necessarily

implemented with such sureness). Security could be found. The business environment

appeared to be reassuringly stable. Objectives could be set and strategies developed to

meet them in the knowledge that the overriding objective would not change.

Such an approach, identifying a target and developing strategies to achieve it,

became known as Management by Objectives (MBO).

Under MBO, strategy formulation was seen as a conscious, rational process. MBO

ensured that the plan was carried out. The overall process was heavily logical and,

indeed, any other approach (such as an emotional one) was regarded as distinctly

inappropriate. The thought process was backed with hard data. There was a belief that

effective analysis produced a single, right answer; a clear plan was possible and, once

it was made explicit, would need to be followed through exactly and precisely.

In practice, the MBO approach demanded too much data. It became overly

complex and also relied too heavily on the past to predict the future. The entire system

was ineffective at handling, encouraging, or adapting to change. MBO simplified

management to a question of reaching A from B using as direct a route as possible.

Under MBO, the ends justified the means. The managerial equivalent of highways were

developed in order to reach objectives quickly with the minimum hindrance from outside

forces.

Henry Mintzberg’s book The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning was first published

in 1994. “The confusion of means and ends characterizes our age,” Henry Mintzberg

observes and, today, the highways are likely to be gridlocked. When the highways are

blocked managers are left to negotiate minor country roads to reach their objectives.

And then comes the final confusion: the destination is likely to have changed during the

journey. Equally, while MBO sought to narrow objectives and ignore all other forces,

success (the objective) is now less easy to identify. Today’s measurements of success

can include everything from environmental performance to meeting equal opportunities

targets. Success has expanded beyond the bottomline.

1.7 Strategic Planning to Strategic Management

Strategic Planning to Strategic Management: Strategic planning was a plausible

invention and received an enthusiastic reception from the business community. But

subsequent experience with strategic planning led to mixed results. In a minority of

firms, strategic planning restored their profitability and became an established part of

the management process. However, a substantial majority encountered a phenomenon,

which was named “paralysis by analysis”: strategic plans were made but remained

unimplemented, and profits/growth continued to stagnate. Claims were increasingly

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 15

made by practitioners and some academics that strategic planning did not contribute to

the profitability of firms. In the face of these claims, Ansoff and several of his colleagues Notes

at Vanderbilt University undertook a four-year research study to determine whether,

when paralysis by analysis is overcome, strategic planning increased profitability of

firms.

Ansoff looked again at his entire theory. His logic was impressively simple – either

strategic planning was a bad idea, or it was part of a broader concept which was not

fully developed and needed to be enhanced in order to make strategic planning

effective. An early fundamental answer perceived by Ansoff was that strategic planning

is an incomplete instrument for managing change, not unlike an automobile with an

engine but no steering wheel to convert the engine’s energy into movement.

Characteristically, he sought the answer in extensive research. He examined

acquisitions by American companies between 1948 and 1968 and concluded that

acquisitions which were based upon an articulated strategy fared considerably better

than those which were opportunistic decisions. The result of the research was a book

titled Acquisition Behavior of US Manufacturing Firms, 1945-1963.

In 1972 Ansoff published the concept under the name of Strategic Management

through a pioneering paper titled The Concept of Strategic Management, which

was ultimately to earn him the title of the father of strategic management. The paper

asserted the importance of strategic planning as a major pillar of strategic management

but added a second pillar – the capability of a firm to convert written plans into market

reality. The third pillar- the skill in managing resistance to change – was to be added in

the 1980s.

Ansoff obtained sponsorship from IBM and General Electric for the first International

Conference on Strategic Management, which was held in Vanderbilt in 1973 and

resulted in his third book, From Strategic Planning to Strategic Management.

The complete concept of strategic management embraces a combination of

strategic planning, planning of organizational capability and effective management of

resistance to change, typically caused by strategic planning. Ansoff says that “strategic

management is a comprehensive procedure which starts with strategic diagnosis and

guides a firm through a series of additional steps which culminate in new products,

markets, and technologies, as well as new capabilities. Strategic Management aimed

to give people at all levels the tools and support they needed to manage strategic

change. Its focus was no longer primarily external, but equally internal – how can the

organization seize and maintain strategic advantage by using the combined efforts of

the people that work in it?

Between 1974 and 1979 Ansoff developed a theory which embraces not only

business firms but other environment-serving organizations. The resulting book titled

Strategic Management, was published in 1979.

Self-confirming Theories: In the 1980s, there was a renewed interest in discovering

ways of dealing with an increasingly complex and changing environment. It was during

this time that the practice of strategy began to move toward a metaphorical application

of an old idea. For many years, management theorists had borrowed the ideas of an

economic theory commonly referred to as “equilibrium theory,” or “equilibrium systems

theory,” as a basis for developing management theory. Basically, the concept was

developed around the idea of linearity (and, to some extent, simplicity). Self-confirming

theories of strategy require the strategist to assume that what the firm has done in the

past will be done in the future. In effect, executives “confirm” that past strategy has

been appropriate by adopting it repeatedly over time.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

16 Business Policy & Strategic Management

Self-confirming theories may be recognized by their historic-simple frame and

Notes mental models. Such theories use terms such as “mission”, core competencies”,

“competitive advantage”, and “sustainable competitive advantage”. They are founded

in the theory of comparative advantage developed by economists David Ricardo

and Adam Smith. The theory of comparative advantage, which suggests that some

countries have unique assets, has become the basis for contemporary strategy.

Strategists modified the idea and called it “competitive advantage”. If it chooses to use

that approach, a firm needs to identify its core competencies, competitive advantage,

and then convert that identification to a mission. In principle, the purpose of the mission

statement is to keep the firm focused upon its unique area of competitive advantage.

Further, the mission is supposed to set boundaries and to “keep it in the box”.

Generally, self-confirming theories force the assumption of a linear mental model, since

it is historic (including present) competencies or resources that provide the constructs

for future strategy.

Thousands of articles and books have been written on the development of

equilibrium-based strategy. The equilibrium-based strategic model involves a

succession of steps that are designed to keep the firm focused upon its historic

competencies. Out of that concept ideas such as SWOT analysis (strengths,

weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) and “five forces” analysis were developed. The

latter is dealt with in Michael Porter’s 1985 book Competitive Strategy. In most cases,

the difference between one key thinker and another is minor at best, but

Michael Porter of Harvard Business School is perhaps the best known of all the

strategy theorists. He has generally been more prolific than the rest. Porter has been

responsible for the writing of numerous books and articles that have been widely

accepted in the field. He has been especially involved in the creation or popularization

of a number of tools that have been widely used in the discipline.

Porter’s first book for practicing managers, Competitive Strategy; Techniques for

Analyzing Industries and Competitors, was first published in 1980. Drawing heavily

on industrial economics (a field of study that tries to explain industrial performance

through economics), he was trying ‘to take these basic notions and create a much

richer, more complex theory, much closer to the reality of competition’. The book defines

five competitive forces that determine industry profitability – Potential Entrants, Buyers

(Customers), Suppliers, Substitutes, and Competitors within the industry. Each of these

can exert power to drive margins down. The attractiveness of an industry depends on

how strong each of these influences is. Competitive Strategy brought together in a

rational and readily understandable manner both existing and new concepts to form a

coherent framework for analyzing the competitive environment.

The realization that he had not been focusing on choice of competitive positioning,

this work led Porter in turn to his interests in the concept of competitive advantage,

the theme of his next major book, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining

Superior Performance (1985). He sought a middle ground between the two polarized

approaches then accepted-on the one hand, that competitive advantage was achieved

by organizations adapting to their particular circumstances; and, on the other, that

competitive advantage was based on the simple principle that the more in-tune and

aware of a market a company is, the more competitive it can be (through lower prices

and increased market share). From analysis of a number of companies, he developed

“generic strategies”: Porter contends that there are three ways by which companies can

gain competitive advantage:

• By becoming the lowest cost producer in a given market

• By being a differentiated producer (offering something extra or special to

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 17

charge a premium price)

Notes

• Or by being a focused producer (achieving dominance in a niche market)

Porter insisted that though the “generic strategies” existed, it was up to each

organization to carefully select which were most appropriate to them and at which

particular time. The “generic strategies” are backed by five competitive forces which

are then applied to “five different kinds of industries” (Fragmented, Emerging, Mature,

Declining, and Global).

To examine an organization’s internal competitiveness, Porter advocates the use

of a ‘value chain’ –analysis of a company’s internal processes and the interactions

between different elements of the organization to determine how and where value is

added. A systematic way of examining all the activities a firm performs and how they

interact is essential for analyzing the sources of competitive advantage. The value

chain disaggregates a firm into its strategically relevant activities in order to understand

the behavior of costs and the existing and potential sources of differentiation. A firm

gains competitive advantage by performing these strategically important activities

more cheaply or better than its competitors. Each of these activities can be used to

gain competitive advantage on its own or together with other strategically important

activities. Here, the concept of linkages (relationships between the way one value

activity is performed and the cost or performance of another) becomes relevant. These

linkages need not be internal – they can equally well be with suppliers and customers.

Viewing every thing a company does in terms of its overall competitiveness, argues

Porter, is a crucial step to becoming more competitive.

This has led to the myth of “sustainable competitive advantage”. In reality, any

competitive advantage is short-lived. If a company raises its quality standards and

increases profits as a result, its competitors will follow. If a company says that it

is reengineering, its competitors will claim to be reengineering more successfully.

Businesses are quick to copy, mimic, pretend and, even, steal. The logical and

distressing conclusion is that an organization has to be continuously developing

new forms of competitive advantage. It must move on all the time. If it stands still,

competitive advantage will evaporate before its very eyes and competitors will pass.

The dangers of developing continuously are that it generates, and relies on, a

climate of uncertainty. The company also runs the risk of fighting on too many fronts.

This is often manifested in a huge number of improvement programs in various parts

of the organization which give the impression of moving forward, but are often simply

cosmetic.

Constantly evolving and developing strategy is labeled ‘strategic innovation”. The

mistake is to assume that strategic innovation calls for radical and continual major

surgery on all corporate arteries. Continuous small changes across an organization

make a difference. “We did not seek to be 100 percent better at anything. We seek to

be one percent better at 100 things,” says SAS’s Jan Carlzon.

Porter would suggest that his “five forces model” and SWOT allow for nonlinear

analysis, but most would agree that the overlaying of a linear mental model (self-

confirming theory) on top of any nonlinear analysis would render any such argument

questionable.

Jay Barney is often credited with popularizing an adaptation of the equilibrium-

based model, called the “resource view” of the firm. This particular view – that a firm’s

resources must also be analyzed and understood in developing corporate strategy –

might simply be viewed as an addition to the traditional self-confirming theories.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

18 Business Policy & Strategic Management

The equilibrium-based strategic model involves a succession of steps that are

Notes designed to keep the firm “in the box” or focused upon its historic competencies. Some

might argue that the use of SWOT analysis avoids this problem, since it analyzes the

firm’s strengths and weaknesses. That generally does not hold true, however, because

the assumption that the firm’s current/historic strengths will serve the company well in

the future tends to override any attempts to engage in discontinuous change.

From the early 1980s to the mid-1900s, approaches based on the equilibrium theory

repeatedly failed, and the level of dissatisfaction with this particular approach grew.

The new global competitive environment that emerged in the late 1980s demanded a

solution. TQM gained a great deal of popularity through the early 1990s, but it soon

fell far short of being a holistic solution. The generally accepted failure rate for TQM

initiatives during this period was over 80%. Failure to understand the critical role that

quality plays in corporate success can be disastrous, but TQM cannot replace strategy,

and it is wrong to believe that quality is all a company needs to be competitive. Quality

is simply the price of admission to play the game. Once in the game, it is strategy that

must drive organizational activities.

In the early 1990s, major consulting firms were overwhelmed with clients who

wanted to use process re-engineering as a solution – for everything from sagging profits

to product development cycles. Like TQM, process re-engineering failed to deliver,

with a failure rate of around 70%. As a result of these failures, many people began to

suggest that the real issue was change – and the usual preponderance of books soon

hit the market. However, once again, the general view was that the majority of change

initiatives added little value to the bottom line.

Discussions with a number of senior executives reveal that most people have given

up on the traditional strategic approach, which is based on mission statements and core

competencies. Interestingly, though, most of their companies still use that traditional

approach. It is important to understand that self-confirming theories of strategy remain

the most frequently used at this time, with well over 90% of all companies making use

of the approach, or of some hybrid that is based upon it. Why do people continue to use

the approach if they no longer trust it? There are a number of answers to that question.

First, most undergraduate and graduate schools still teach that approach, almost

exclusively. Second, the approach is easy to learn and understand. Third, it is

comforting, because it focuses upon what some have called “self-confirming theory” – it

confirms that what we have done in the past is good, since we are going to continue

to do in the future what we have done in the past (i.e. our future strategy will be based

upon our historic competencies).

As early as 1989, Rosabeth Moss Kanter was pointing out, in When Giants Learn

to Dance, the problems with another historic-linear approach, which she refers to as

“excellence”. People tend to love the idea of excellence. It makes for a great book title,

whether it involves “searching for excellence” or “building something to last”. Alongside

these books were the “7 Things That Companies do” titles, which again focused upon

excellence in practice.

“Benchmarking” is a variant of the excellence practice. The underlying mental model

suggests that something someone did somewhere at some point in time will work for

their firm where it is today (and tomorrow). The reality is that it might work but it might

not. Therein lies the problem with linear (simple) historic mental models.

Almost without exception, the companies featured in the excellence books

encountered problems within a few years of the book’s publication. This is true even for

James C. Collins and Jerry I Porras’ Built to Last.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 19

As a result of the apparent failure of the “self-confirming theories”, strategy theorists

have searched for alternatives. Notes

The Reality of Competitive Environments: The new competitive world has moved

from a linear (or highly predictable, somewhat simple) state to a non-linear (or

highly uncertain, complex) state. That does not mean that nothing will continue to be

predictable. It means that in the future historic relationships will most likely not be the

same as they were in the past.

In 1980, Ansoff published a paper which represented another step in the

development of practical strategic management which concerned the development

of practical tools for managing adaptation of firms to turbulent environments. The

paper, called Strategic Issue Management, presented a way of adapting a firm to the

environment, when environmental change develops so fast that strategic planning

becomes too slow to produce timely responses to surprising threats and opportunities.

From 1991 to 2001, rapid change and high levels of complexity have characterized

the global competitive environment. As the rate of environmental change accelerates,

and the level of complexity rises, the ‘rules of the game” change. Such changes mean

that the firm must change in harmony with the environment. If it does not, ultimately the

environment will eliminate it. For the company that does not change in harmony with the

environment, the result is deterioration and, perhaps, demise.

Companies are complex systems operating within complex dynamic systems. In

every case, the complexity as well as the rate of system change will be different at

different points of time. There are a number of implications for this reality.

• Simple-historic or simple-linear strategy is insufficient to prepare a firm for

environments that involve varying levels of complexity and rates of change.

• As a complex system, every aspect off the firm (not just its strategies) must be

balanced with the future environment if the firm is to maximize performance.

• Imbalances between the firm and the environment result in diminished

performance, or in some cases, the demise of the firm.

Put simply, complex environmental systems (the competitive environment) require

complex mental models of strategy if the firm is to succeed. The use of linear mental

models in environments of varying complexity and rate of change is a prescription for

failure.

Henry Mintzberg has famously coined the term “crafting strategy,” whereby strategy

is created as deliberately, delicately, and dangerously as a potter making a pot. To

Mintzberg strategy is more likely to “emerge,” through a kind of organizational osmosis,

than be produced by a group of strategists sitting round a table believeing they can

predict the future.

Mintzberg argues that intuition is “the soft underbelly of management” and that

strategy has set out to provide uniformity and formality when none can be created.

Another fatal flaw in the conventional view of strategy is that it tended to separate

the skills required to develop the strategy in the first place (analytical) from those

needed to achieve its objectives in reality (practical).

Mintzberg argues the case for what he labels ‘strategic programming’. His view is

that strategy has for too long been housed in ivory towers built from corporate data and

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

20 Business Policy & Strategic Management

analysis. It has become distant from reality, when to have any viable commercial life

Notes strategy needs to become completely immersed in reality.

In an era of constant and unpredictable change, the practical usefulness of strategy

is increasingly questioned. The skeptics argue that it is all well and good to come up

with a brilliantly formulated strategy, but quite another to implement it. By the time

implementation begins, the business environment is liable to have changed and be in

the process of changing even further.

Mintzberg’s most recent work is probably his most controversial. “ Strategy is not

the consequence of planning but the opposite: its starting point,” he says countering the

carefully wrought arguments of strategists, from Igor Ansoff in the 1960s to the Boston

Consulting Group in the 1970s and Michael Porter in the 1980s. The Rise and Fall of

Strategic Planning is a masterly and painstaking deconstruction of central pillars of

management theory.

The divide between analysis and practice is patently artificial. Strategy does not stop

and start, it is a continuous process of redefinition and implementation. In his book, The

Mind of the Strategist, the Japanese strategic thinker Kenichi Ohmae says: “In strategic

thinking, one first seeks a clear understanding of the particular character of each

element of a situation and then makes the fullest possible use of human brain power to

restructure the elements in the most advantageous way. Phenomena and events in the

real world do not always fit a linear model. Hence the most reliable means of dissecting

a situation into its constituent parts and reassembling them in the desired pattern is

not a step-by-step methodology such as systems analysis. Rather, it is that ultimate

nonlinear thinking tool, the human brain. True strategic thinking thus contrasts sharply

with the conventional mechanical systems approach based on linear thinking. But it also

contrasts with the approach that stakes everything on intuition, reaching conclusions

without any real breakdown or analysis.”

When future could be expected to follow neat linear patterns, strategy had a clear

place in the order of things. Organizations are increasingly aware that, as they move

forward, they are not going to do so in a straight unswerving line. The important

ability now is to be able to hold on to a general direction rather than to slavishly

follow a predetermined path. Now, the neatness is being upset, new perspectives are

necessary. The new emphasis is on the process of strategy as well as the output.

Such flexibility demands a broader perspective of the organization’s activities and

direction. This requires a stronger awareness of the links between strategy, change,

team-working, and learning. Strategy is as essential today as it ever was. But, equally,

understanding its full richness and complexity remains a formidable task.

Kenichi Ohmae argues that an effective strategic plan takes account of three main

players – the company, the customer, and the competition – each exerting their own

influence. The strategy that ignores competitive reaction is flawed; so is the strategy

that does not take into account sufficiently how the customer will react; and so, of

course, is the strategic plan that does not explore fully the organization’s capacity to

implement it.

Kenichi Ohmae says that a good business strategy “is one, by which a company can

gain significant ground on its competitors at an acceptable cost to itself.” He believes

there are four principal ways of doing this:

1. Focus on the key factors for success (KFSs). Ohmae argues that certain

functional or operating areas within every business are more critical for

success in that particular business environment than others. If Organization

concentrate effort into these areas and their competitors do not, this is a source

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 21

of competitive advantage. The problem, of course, is identifying what these key

factors for success are. Notes

2. Build on relative superiority. When all competitors are seeking to compete on

the KFSs, a company can exploit any differences in competitive conditions.

For example, it can make use of technology or sales networks not in direct

competition with its rivals.

3. Pursue aggressive initiatives. Frequently, the only way to win against a much

larger, entrenched competitor is to upset the competitive environment, by

undermining the value of its KFSs – changing the rules of the game by

introducing new KFSs.

4. Utilizing strategic degrees of freedom. By this tautological phrase, Ohmae means

that the company can focus on innovation in areas which are untouched by

competitors.

“In each of these four methods, the principal concern is to avoid doing the same

thing, on the same battle-ground, as the competition,” Ohmae explains.

Kathryn Rudie Harrigan’s first book, Strategies for Declining Businesses focused

on declining businesses. Harrigan believes there is a life-cycle for businesses and they

need to revitalize themselves constantly to prevent decline. From declining businesses,

Harrigan moved on to the subject of vertical integration and the development of

strategies to deal with it. A central premise of the framework she developed was that,

as firms strived to increase their control over supply and distribution activities, they

also increased their ultimate strategic inflexibility (by increasing their exit barriers). In

search of more flexible approaches she carried out lengthy research into joint ventures.

Despite their boom, Harrigan’s research showed that between 1924 and 1985 the

average success rate for joint ventures was only 46 per cent and the average life span

a meager three and a half years. In her two books on joint ventures, Harrison argued

they will become a key element in competitive strategy. The reasons she gave for this

were: economic deregulation, technological change, increasing capital requirements in

connection with development of new products, increasing globalization of markets. She

predicted:

1. One-on-one competition will be replaced by competition among constellations

of firms that routinely venture together.

2. Teams of co-operating firms seeking each other out like favorite dancing

partners will soon replace many current industry structures where firms stand

alone.

3. To cope with these changes, managers must learn how to co-operate, as well

as compete, effectively.

Harrigan’s later work focused on mature businesses. Managing Maturing

Businesses (1988) examined ‘the second half of a business’s life’ or, as it is more

dramatically put, the endgame. She has coined the phrase ‘The last iceman always

makes money’, which she explains as ‘The last surviving player makes money serving

the last bit of demand, when the competitors drop away.’ The importance of her work

in this area was given credence by the fact that over two-thirds of the industries within

mature economies were experiencing slow growth or negative growth in demand for

their products.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

22 Business Policy & Strategic Management

Ameliorating the pain and avoiding premature death have been the motivating

Notes factors of Harrigan’s work. Harrigan’s argument is that endgame can be highly profitable

if companies adopt a coherent strategy sufficiently early. The strategic options are:

1. Divest now – the first company out usually gets the highest price; later leavers

may not get anything.

2. Last iceman –focusing on customer niches which will continue long-term and

will be prepared to pay a premium.

3. Selective shrinking – taking the profitable high ground and leaving the less

profitable low ground to the competitors.

4. Milking the business – the last option, but none the less a practical alternative

in many situations.

1.8 Complex Systems Strategy

Complexity-based approaches or “complex adaptive systems,” were developed

in response to the apparent failure of equilibrium-based approaches. Complexity-

based thinkers will fall into a number of different camps. The majority believe that the

environment must be understood in terms of its complexity, chaos, and ecological

constructs. This group subscribes to the Darwinian hypotheses (upward evolution of a

system) as a metaphor for the business environment. This kind of thinking has resulted

in the idea of “self-organizing” companies.

The complexity group falls into two categories. One might be called a “pure”

complexity-based group, the other a “hybrid”. In the case of the former, theorists

generally apply the concept of emergence to every situation. According to this group

predictive modeling is rendered useless by the chaotic nature of the environment. They

would suggest that any attempt to plan for the future is pointless.

The hybrid group also assumes that the Darwinian hypotheses may be used as a

metaphor for business systems. This particular group of thought is based upon the idea

that the firm may compete on the edge of chaos, that is in a state in which the system

is complex adaptive, but at the same time with a minimal level of predictability in the

system (Brown and Eisenhardt’s Competing on the Edge). This group of thinkers has

combined the emergent (complex-historic) approach with the extrapolation (simple-

future) approach

1.8.1 Emergence:

The emergence camp is divided into at least two or three distinctive groups.

Emergence-based theorists begin with the idea of complex systems and chaos theory.

Some suggest that the ability to deal with complexity on a futuristic basis is impossible.

Others suggest that it is possible to understand some aspects of futuristic systems. A

third group imposes naturalistic ecological presuppositions in its theory.

Ralph Stacey and Henry Mintzberg tend to hold to the view that it is simply not

possible to consider future complex environments. As a result they suggest that

the strategist must wait for events to occur, or emerge, then develop strategy. This

approach of “incrementalism” involves the “after the fact” development of strategy for

discontinuous events. Mintzberg suggests that, as discontinuous events occur, the firm

should dynamically craft strategy.Stacey generally agrees with Mintzberg, but in his

book ‘Managing the Unknowable’, he additionally suggests that it is possible to create

organizations that are designed to deal with ambiguity and complexity.

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 23

Others involve themselves in apparently self-defeating arguments. In The Fifth

Discipline, Peter Senge advances the idea of systems thinking and suggests that it Notes

is possible to observe complex systems and make reliable inferences about such

systems. On the other hand, in the multi-author work The Dance of Change, he tends to

take a purely Darwinian emergence view.

The emergent or complex-historic group of strategists is by far the fastest-growing

group in the field. As those who see the failure of self-confirming theories seek

alternatives, the focus on complexity by the emergent group seems to make a lot of

sense.

1.8.2 Chaos and Complexity:

Around the mid-1950s, there had been a certain amount of investigation into the

idea of cybernetics, or the study of processes. That led some people to think about the

competitive environment in a very different way. Chaos and complexity theory were

introduced. By the early 1990s, complexity theory had taken on a life of its own. At

about the same time, the idea of systems thinking was popularized, particularly, in Peter

Senge’s 1990 book The Fifth Discipline.

The period was characterized by a blending of disciplines, including natural science,

social sciences, and business. A number of business theorists moved on from the

metaphor of chaos theory in business to complexity theory. Chaos theory had dealt with

the unpredictable processes that were observable in science. Those who moved on to

complexity theory added an interesting twist to the basic idea of complexity. Complex

systems thinking has to do with the fact that the global system or environment is made

up of a limitless number of other systems. Theorists hypothesize that complex systems

may behave in much the same way as the molecules in a glass of water, which interact

randomly.

1.8.3 Systems Thinking:

Another approach for dealing with complex environments is called systems thinking.

Proponents of systems thinking believe that it is possible to consider complex issues

and to make “reasonable inferences” about the outcomes of such complex systems.

Systems thinking has been widely discussed in corporate circles, but few companies

actually utilize the approach, especially at the senior executive level – where it could

be most beneficial. Those few leaders who have the intuitive ability to think in terms of

complex systems, are and will continue to be, highly successful.

1.8.4 Darwinian Theory:

Alongside this hypothesis relating to complex systems, the idea of using Darwin’s

theory of evolution as a metaphor for complexity was developed. Charles Darwin’s

concept focused upon two ideas: first, the idea of natural selection, or the survival of

the fittest; second, the idea of evolution. His concept of evolution was based upon

the hypothesis that matter was constantly in a state of moving from a lower level of

complexity to a higher level of complexity. In his view, this accounted for the similarities

between monkeys, apes, and the different races of humans.

Scientific evidence generally refutes these particular views (along with others held

by Darwin), but Darwin’s hypothesis has none the less been adapted metaphorically to

complexity theory as it is applied in business. Those who subscribe to the theory say

that the evolution (from lower complexity to higher complexity) that occurs “naturally”

in nature must apply equally to businesses. Complexity management theorists go on

to suggest that one of the goals of every manager should be to allow the business to

emulate nature by “self-organizing”.

This theme is clearly revealed in Peter Senge’s 1999 book The Dance of Change. In

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

24 Business Policy & Strategic Management

one article in the book, entitled “The leadership of profound change-toward an ecology

Notes of leadership”, Senge suggests that leaders need to understand more about nature and

to manage with that in mind. The CEO, according to Senge, is not the solution to driving

meaningful change in the organization.

In most cases, the complexity-based theorists assume the Darwinian hypotheses

(upward mutation or evolution of complex natural systems) as a metaphor for

management and strategy theory. This idea is developed in what is called “self-

organization”. It is also an integral part of the complexity theorists’ response to the linear

economic model referred to as “equilibrium theory”, which is called “complex adaptive

systems” theory.

The evidence clearly invalidates the Darwinian hypotheses. “Complex dynamic

systems” as an idea is finding support not only as a way of describing the natural

environment, but also as a reasonable metaphor for developing management and

strategy theory. This approach deals with complex systems without the prepositional

fallacies related to complex adaptive systems theory.

Shona L. Brown and Kathleen M. EisenhardtBrown and Eisenhardt’s book

Competing on the Edge (1998) displays their work as somewhat of a hybrid of the

complex adaptive systems approach (including the Darwinian hypotheses) and the

self-confirming schools of thought. In essence, Brown and Eisenhardt suggest that

the firm is competing in complex environments, and thus must deal with high levels

of uncertainty. Their view is that the firm is constantly in a process of changing its

competencies. There is some dissonance between their adoption of competencies and

their prescriptions for dynamic corporate strategy.

Henry Mintzberg The work of Canadian, Henry Mintzberg counters much of

the detailed rationalism of other major thinkers. He falls in the complex-historic

(emergence) category of strategists, although, unlike most in that camp, he does not

appear to have adopted the Darwinian metaphor. Mintzberg believes in incremental

responses to changes as they emerge in the environment. It is clear that he holds to the

idea of a complex environment, yet he also seems to believe that it is not possible to

anticipate or prepare proactively for discontinuous events. His views are the antitheses

of Ansoff’s.

Ralph Stacey His book Managing the Unknowable (1992) was really ahead of the

curve among the work of the proponents of complex adaptive systems. Stacey’s work

differs from that of many of the others in that particular school, since he suggests that

companies need to prepare proactively for complexity.

1.9 Complex Dynamic Systems

The application of a Darwinian-based theory of complexity has resulted in an

alternative to the equilibrium theory of economics – “complex adaptive systems” –

which again, proposes that the economic system is characterized by progressive

upward evolution.

The positive aspect of the theory is that it turns managers toward thinking

about complex systems. There is no doubt that linear thinking (equilibrium-based

management theory) can damage a company, but the absence of scientific support

for “adaptive systems” (in either nature or in business) may also be problematic when

trying to build corporate strategy.

A number of people are now using the idea of complex dynamic systems as a way to

think about the competitive environment. Moving from the Darwinian presupposition of

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 25

evolution to recognition of the complex nature of the environment may present a better

opportunity for the corporate strategist. Notes

There is currently a clear trend toward complexity-based corporate strategy.

Emerging research supports the fact that moving from a linear to a non-linear complex

mental model of the environment will help managers to lead a more profitable

organization.

C. K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel in their book ‘Competing for the Future’ first

published in 1994. Their work has gone through a number of cycles, or changes.

Early on, it seemed to focus on self-confirming theories. However, they were quick

to comprehend the apparent failure of that model, and began to move more toward

a complexity-based model. In their later works they have focused on anticipating the

complex nature of the future environment. At the same time they are not proponents

of strategy based on complex adaptive systems (the Darwinian hypotheses). A very

positive aspect of their work is their emphasis on proactive strategies for dealing with

future uncertainty.

The phrase “core competencies” has now entered the language of management. In

layman’s terms, core competencies are what a company excels at. Gary Hamel and

C K Prahalad define core competencies as “the skills that enable a firm to develop a

fundamental customer benefit.” They argue that strategic planning is neither radical

enough nor sufficiently long-term in perspective. Instead its aim remains incremental

improvement. In contrast, they advocate crafting strategic architecture. The

phraseology is unwieldy, but means basically that organizations should concentrate on

rewriting the rules of their industry and creating a new competitive industry.

Richard D’Aveni The best-known work of Richard D’Aveni of Dartmouth College is

Hypercompetition (1994), in which he overtly takes on the traditional self-confirming

strategic approaches. Based upon his observations of the real world, the book

concludes that the world is no longer linear, and does not reward those who use linear

approaches to create corporate strategy. In its place, he suggests, the planner needs to

consider a new approach. In assessing the new corporate world, he makes a number of

insightful observations in Hypercompetition:

• Firms must destroy their competitive advantage to gain advantage.

• Entry barriers work only if others respect them.

• A logical approach is to be unpredictable and irrational.

• Traditional long-term planning does not prepare for the short term.

• Attacking competitor’s weaknesses can be a mistake. Traditional approaches

such as SWOT analysis may not work in a hypercompetitive environment.

• Companies have to compete to win, but competing makes winning more

difficult.

D’Aveni builds the case for a complex environment and the need to change the

organization continually in response to the environment, then proposes an answer to

his argument about the “need for a dynamic theory”: the 7-S approach.

• Superior stakeholder satisfaction.

• Strategic soothsaying.

• Positioning for speed.

• Shifting the rules of the game.

• Signaling strategic intent.

• Simultaneous and sequential strategic thrusts

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

26 Business Policy & Strategic Management

At the heart D’Aveni’s ideas is his conclusion that companies need to be focused

Notes upon disrupting the market. He suggests that there are three critical factors that enable

a firm to deliver sustainable disruption in the market:

1. A vision for disruption.

2. Capabilities for disruption (the organization).

3. Product/market tactics used to deliver disruptions.

There are a number of similarities between the work of Ansoff and that of D’Aveni.

Both suggest that the environment involves some level of complexity and rate of

change. Both propose a contingency theory approach – that is, the organization must

be designed to respond to the present and future environment. Both believe that

the environment of the 1990s began a new period of highly turbulent, unpredictable,

changing environments.

1.9.1 Hybrid Systems:

One of the more questionable adaptations of the various theories comes from those

who attempt to combine complex adaptive systems and equilibrium-based theory.

These theorists suggest that strategists should apply complex adaptive systems

approaches to their strategy, while at the same time developing historic (or even new)

competencies. Clearly there are problems with this combination.

Observing the global environment, and accepting the fact that there are two

environmental issues that strategists must address – complexity and rate of change –

it is clear that an organization must be continually changing in nonlinear terms both in

speed and in complexity. Rosabeth Moss Kanter’s useful idea of “contingency theory”

(presented in When Giants Learn to Dance) rightly suggests that the organization must

be able to respond contingently to future changes in the environment. Her approach

is similar to W. R. Ashby’s “requisite variety theorem” explained in his Introduction to

Cybernetics.

The modified Ansoff Model is also a hybrid. On one hand, a complex dynamic

systems approach is taken. On the other, an emergence approach is viewed as part of

the firm’s ability to respond to discontinuous events. Then, the firm is assessed using a

complex model to determine its ability aggressively to create the future strategy the firm

needs and the responsiveness capabilities of the firm to address discontinuous events

as they emerge.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter Also from Harvard Business School, the fact that Kanter

rejects the self-confirming approach to the development of strategy in favor of

contingency design is an important underpinning of her work. She believes that the

strategist must begin with an understanding of the future environment, then contingently

design the firm around that understanding. In her book When Giants Learn to Dance

(1990), she offers seven ideas that describe managers who will be successful in the

new corporate environment:

1. They operate without the power of the might of the hierarchy behind them

(leadership vs. positional power).

2. They can compete (internally) without undercutting competition).

3. They must have the highest ethical standards.

4. They possess humility.

5. They must have a process focus.

6. They must be multifaceted and ambidextrous (work across business units/

flexible).

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

Business Policy & Strategic Management 27

7. They must be willing to tie their rewards to their own performance.

Evan Dudik Strategic Renaissance (2000) by Evan Dudik takes a complex systems Notes

approach to strategy by suggesting that the planner must understand the level of

uncertainty of the future environment (very similar to Ansoff’s turbulence) and, at the

same time, that the firm must create a complex adaptive system (the firm itself) if it is

to deal with that uncertainty. It is clearly an excellent application of contingency theory.

Dudik’s book covers all of the positives related to developing complex mental models

and is excellent in presenting contingency approaches to the development of corporate

strategy.

1.9.2 Predictive Modeling:

Predictive modeling involves a complex mental model and a futuristic (as opposed

to historic) strategic frame. Since complex-futuristic approaches involve complexity,

there are a number of types of those approaches, including some hybrids. Even though

some of the approaches are especially concerned with complexity, some tend to be less

holistic or whole-system than others.

AIS-“Artificial Intelligence Simulation”:

The first approach might be called or AIS, which involves the creation of a computer-

based model in which key variables can be manipulated. The researcher might identify

10 independent variables that appear to drive certain outcomes (dependent variables).

In some cases it is possible to base the behaviors of the variables on statistically based

relationships. That adds power to the model. Regardless, the AIS process allows

the researcher to manipulate variables in order to develop some level of predictive

confidence in the future. In some ways, AIS can be similar to war gaming.

Scenarios and war gaming can be quite helpful in complex environments.

Scenarios: The concept of scenario planning was pioneered by oil giant Shell.

Creating one single strategic plan to be followed with military precision simply didn’t

work in practice. As circumstances changed, the strategic plan also needed changing

and executives were either constantly going back to the drawing board or trying to

push through a plan that was no longer appropriate. The longer the planning horizon,

the worse the problem became. Shell’s answer was to make not one but a number

of sets of assumptions about the future environment. At its simplest, these would be

optimistic, pessimistic, and straightline. Any one of these scenarios could happen,

but managers now drew up plans that followed the most likely series of events, while

building in frequent evaluation points where one of the alternative scenarios could take

over. In effect, what they were doing was thinking through the implications of necessary

deviations of a plan sufficiently far ahead to be able to implement them at minimum cost

and effort.

Scenarios are classified as complex-future models (predictive modeling) and they

have been successfully used for the development of strategy for complex environments

for a number of years. Scenarios involve the analysis of future driving forces in an

environment and the consideration of a range of possible outcomes.. Scenarios tend to

focus on a very narrow area of the future, but ideally will attempt to account for driving

forces, or independent variables that could have an impact upon the area being studied.

Scenarios have two purposes: first, a multiple scenario (i.e. three or four possible

scenarios about a specific issue) can provide a complex systems overview of an issue;

second, they can be extremely helpful in driving organizational learning.

A number of comments have been made regarding “driving” organizational learning

and “managing” resistance to change. It is important to remember that dissonant data

Amity Directorate of Distance & Online Education

28 Business Policy & Strategic Management

(information that indicates that the future environment will shift, and that the “rules of the

Notes game” will change) is more often rejected by senior managers than accepted. Managing

such resistance (which can be measured using the modified Ansoff model) is quite

important from a profit standpoint.