Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Part 1: An Old Question Asked Anew: Francis Fukuyama

Hochgeladen von

Lola LolaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Part 1: An Old Question Asked Anew: Francis Fukuyama

Hochgeladen von

Lola LolaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Part 1: An Old Question Asked Anew

Francis Fukuyama opens his book by discussing the then-recent events that prompted his

thesis. He begins by discussing the pessimism about historical progress he detects in his

contemporaries. The reason for this is the destructive events of the 20th century, including

two world wars and the rise of many authoritarian and totalitarian regimes. These events

helped to destroy certainties about progress that were common in the 19th century and

have caused some in the West to question the validity and effectiveness of democracy

itself. But Fukuyama wishes to make an opposite case: events in the 1980s and 1990s

offer reason for renewed optimism. He argues the apparent strength of authoritarian states

was always a fiction. Pessimists had mistaken a temporary blip on the road to progress for

a real threat to liberal democracy. He examines first the authoritarian states of the right,

and then the "totalitarian" states of the communist left. Both kinds experienced a series of

crises in the 1970s and 1980s from which few recovered. In both analyses Fukuyama

points to two crises that these kinds of states could not resolve: their inability to manage

rapid economic change and the inevitable crisis of legitimacy. Fukuyama argues his age is

undergoing a global liberal revolution which is ushering in the final stage in a "Universal

History": the worldwide triumph of liberal democracy and capitalism (the economic system

in which the means of production are privately owned and distributed through markets).

Part 2: The Old Age of Mankind

Fukuyama begins this part by laying out the case for a "Universal History," that is, a grand

narrative of human development across history, or the idea that history is the tale of

inexorable (unavoidable) social progress. He traces the ideas of metanarrative history from

classical thinkers up to more modern examples, like Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), Georg

Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), and Karl Marx (1818–83). Fukuyama disagrees with

Marx and believes Hegel's idea of history heading toward liberal democracy was more

accurate. He then proceeds to lay out the first of two mechanisms he believes underpin the

liberal revolution. This is economic, and especially technological, change that means the

ascent of capitalism as the most developed form of human economic activity is inevitable.

He believes technological progress is inevitable because it is tied to scientific progress,

which is, likewise, inevitable and moving in the direction of more and more complete

knowledge.

Planned economies cannot compete with market economies because planners cannot

allocate resources as efficiently as markets can. This means planned economies cannot

adapt quickly enough to technological change; they thus lag behind market economies.

Moreover, he believes the so-called "Asian economic miracle" of the mid-20th century

showed that rapid industrialization and market liberalization did not necessarily lead to the

deprivations communist ideologies said they would. Fukuyama points out, however, that

this economic account of the liberal triumph does not go far enough to explain exactly how

and why it happened. He believes the ascent of liberal economics, whose advantages

seem to Fukuyama self-evident, is easier to explain than the triumph of liberal democracy,

which Fukuyama views as more problematic.

Part 3: The Struggle for Recognition

Fukuyama proceeds to explain why people across the globe have revolted to overthrow

tyrannical regimes and institute liberal democracies. He takes Hegel's conception of history

as a "struggle for recognition" and deploys it for his own purposes. The desire to be

recognized as a human being with worth and dignity is Fukuyama's engine for the ascent of

liberal democracy. He begins by considering the "first man" at the earliest stage of history,

who was engaged in violent struggles for prestige as a way to gain recognition. This is

similar to the conception of early humanity found in English philosophers John

Locke (1634–1704) and Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), which Fukuyama discusses as a

way to introduce his (and Hegel's) preferred understanding of humans as always—across

all class and national divides—engaged in a struggle for personal recognition. Fukuyama

further points out this was not an idea original to Hegel; it comes from classical philosophy

through Greek philosopher Plato (428–348 BCE) in the form of the concept of thymos, or

"spiritedness."

Fukuyama goes on to apply this understanding of thymos as underpinning many

phenomena otherwise thought of as motivated by economics. Workers on strike, for

instance, are not motivated primarily by higher wages or better working conditions but by

their own sense of self-worth, or thymos. For this reason they despise strikebreakers

because strikebreakers call into question the strikers' thymos. The American Civil War

(1861–65), likewise, according to this theory, was caused by thymotic desires rather than

economics. Furthermore, Fukuyama places thymos into his immediate context as one of the

main motivations driving the revolutions against communist regimes in the 1980s.

Returning to Hegel, Fukuyama outlines Christianity's contribution to the Hegelian

conception of humanity. According to Fukuyama, Christianity proposes all humans are

ultimately equal in the eyes of God and articulated a vision of universal human freedom.

For Hegel this means also that all humans possessed thymos and were driven by it to desire

freedom. These principles are made manifest in the "universal and homogenous state" at

the "end of History" which in Fukuyama's view is best represented by the contemporary

United States of America.

Part 4: Leaping Over Rhodes

Part 4 is titled "Leaping Over Rhodes." This phrase refers to one of the fables of Greek

storyteller Aesop (c. 620–560 BCE) about a bragging athlete who exaggerates the distance

of a jump the athlete made when visiting the city of Rhodes. The athlete boasts that many

people witnessed the incredible leap and could prove the athlete's story. However, those

listening to the athlete's story respond that there is no need for witnesses of what

happened in Rhodes. The athlete should go ahead and perform the same incredible leap

right now. The fable is a well-known cautionary tale against boasting.

Having outlined his historical argument, Fukuyama begins to explain what it means to live

in the "end of History" and what problems the future holds. One of these is the incomplete

application of liberal democracy across the world. He identifies two main opponents of

liberal democracy: religion and nationalism. Fukuyama believes it is only in the creation of

civic and democratic cultures that democracy can truly take root. A strong "democratic

tradition" is not necessary, but statesmen and people alike must be willing to practice

democracy and see it flourish. Fukuyama then examines the "work ethic" that is derived

(like democracy) from thymos rather than pure economic motives. This work ethic differs

from culture to culture, and Fukuyama uses this to explain why, although they may adopt

democracy, economic and social differences among nations will persist. Authoritarianism is

another aspect of culture Fukuyama ponders. He sets the roots of authoritarianism in

"group cultures" as found in Southeast Asia. It is these cultural factors that, for Fukuyama,

create the persistence of authoritarian politics in places like Singapore.

Having established to his satisfaction that competition at the end of history will be between

cultures, he then points to what a foreign policy of the period will look like. He attacks the

foreign policy "realism" of the Cold War as treating contemporary facts about nations and

the balance of power as set facts that have to be accommodated. Fukuyama stresses that

these "facts" were contingent on a set of historical circumstances that are now changed by

the overthrow of communism. Realism is thus unrealistic as a basis for a new foreign

policy. Fukuyama posits a growing distinction between the "historical" world in which

nations, nationalism, and imperialism persist, and the "post-historical" world where cultures

are drawn together through ties of international trade and cooperation.

Part 5: The Last Man

Fukuyama spends the final section of his text considering the challenges and problems that

face the "last man" at the end of History. He questions whether the victory of liberalism (the

political system that places highest emphasis on preserving personal liberty) and capitalism

will ultimately leave inhabitants of "post-history" unsatisfied and cause backsliding into

older modes of being. One problem posed to the "post-history" world is the persistence of

megalothymia, the desire to be recognized as greater than others. Fukuyama believes this

to have been tamed but not eradicated by the liberal state. Another problem Fukuyama

foresees is that liberal democracy places too much emphasis on the rights of citizens and

not enough on citizens' duties to their communities and society. This means communities,

which Fukuyama holds to be the bedrock of an orderly and successful society, will begin to

break down. He closes by making the case that, in the future, a directional history such as

that which he proposes will become self-evident to observers.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The End of History and The Last Man - Francis Fukuyama Book ReviewDokument3 SeitenThe End of History and The Last Man - Francis Fukuyama Book ReviewSAURABH SINGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History and The Last ManDokument4 SeitenThe End of History and The Last ManjbahalkehNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History and The Last ManDokument8 SeitenThe End of History and The Last ManChiradip SanyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fukuyamas Book Review PDFDokument6 SeitenFukuyamas Book Review PDFnemanjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fokuyama Reflection Paper LacoDokument11 SeitenFokuyama Reflection Paper LacoRikki Marie PajaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Francis FukuyamaDokument54 SeitenOn Francis FukuyamaChris Hughes100% (1)

- "The End of History and The Last Man": FukuyamaDokument20 Seiten"The End of History and The Last Man": Fukuyamamartinshehzad100% (1)

- A Brief Analysis of Fukuyama's Thesis ''The End of History - (#118847) - 100889Dokument3 SeitenA Brief Analysis of Fukuyama's Thesis ''The End of History - (#118847) - 100889Ichraf KhechineNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critical Review of The End of HistoryDokument4 SeitenA Critical Review of The End of HistorynemanjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Summary Fukuyama The End of History or The Last ManDokument2 SeitenBook Summary Fukuyama The End of History or The Last ManNadiya100% (2)

- The End of History and The Last Man by Francis Fukuyama - Issue 106 - Philosophy NowDokument3 SeitenThe End of History and The Last Man by Francis Fukuyama - Issue 106 - Philosophy NowBanderlei SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Freedom's Secret Recipe: March/April 2012 Review EssayDokument4 SeitenFreedom's Secret Recipe: March/April 2012 Review EssayGrzegorzKossonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History Notes (By Ali Hameed Khan)Dokument1 SeiteThe End of History Notes (By Ali Hameed Khan)Mazhar FareedNoch keine Bewertungen

- F Fukuyama End of History and The WorldDokument8 SeitenF Fukuyama End of History and The WorldAleezay ChaudhryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critically Assess The Claim That The End of The Cold War Represented A Victory For Liberal CapitalismDokument8 SeitenCritically Assess The Claim That The End of The Cold War Represented A Victory For Liberal CapitalismAjay ManchandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- End of HistoryDokument1 SeiteEnd of HistoryHani AmirNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History and The Last ManDokument25 SeitenThe End of History and The Last ManBagas MaulanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explain The End of History According To Francis Fukuyama IdeasDokument2 SeitenExplain The End of History According To Francis Fukuyama IdeasKelvin KipngetichNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History and The Last Man by Francis Fukuyama ReviewDokument5 SeitenThe End of History and The Last Man by Francis Fukuyama ReviewDinu Bălan100% (1)

- Socialism Unbound: Principles, Practices, and ProspectsVon EverandSocialism Unbound: Principles, Practices, and ProspectsNoch keine Bewertungen

- the-end-of-history-and-the-last-man-Reflection-paper-Dalisan JennyDokument12 Seitenthe-end-of-history-and-the-last-man-Reflection-paper-Dalisan JennyRikki Marie PajaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Francis Fukuyama's End of History and the Last ManVon EverandSummary of Francis Fukuyama's End of History and the Last ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- PakistanDokument4 SeitenPakistanM waqas MarwatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review - Identity Francis FukuyamaDokument4 SeitenBook Review - Identity Francis FukuyamaSardar Abdul BasitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pol Science Random NotesDokument121 SeitenPol Science Random NotesMuhammad HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Between Utopia and Tyranny - Fascination and Terror of CommunismVon EverandBetween Utopia and Tyranny - Fascination and Terror of CommunismNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Specter of Democracy: What Marx and Marxists Haven't Understood and WhyVon EverandThe Specter of Democracy: What Marx and Marxists Haven't Understood and WhyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of History and The Last Man - : by Francis FukuyamaDokument10 SeitenThe End of History and The Last Man - : by Francis FukuyamaCharvi KwatraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismVon EverandThe Modern State and Its Enemies: Democracy, Nationalism and AntisemitismNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authoritarian Socialism in America: Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist MovementVon EverandAuthoritarian Socialism in America: Edward Bellamy and the Nationalist MovementNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gray-Identity PoliticsDokument6 SeitenGray-Identity PoliticsWalterNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalization EraVon EverandThe History of Human Rights: From Ancient Times to the Globalization EraBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (13)

- Parallelism: a Handbook of Social Analysis: The Study of Revolution & Hegemonic WarVon EverandParallelism: a Handbook of Social Analysis: The Study of Revolution & Hegemonic WarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy, Volume IIIVon EverandThe Discipline of Western Supremacy: Modes of Foreign Relations and Political Economy, Volume IIINoch keine Bewertungen

- The Multidimensional Crisis and Inclusive DemocracyDokument292 SeitenThe Multidimensional Crisis and Inclusive DemocracyXanthiNoch keine Bewertungen

- M.Pol - Thought Biopolitics SummaryDokument3 SeitenM.Pol - Thought Biopolitics SummaryClara PovedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAF 9181 ReactionDokument3 SeitenPAF 9181 ReactionepirrysNoch keine Bewertungen

- History, Power, Ideology: Central Issues in Marxism and AnthropologyVon EverandHistory, Power, Ideology: Central Issues in Marxism and AnthropologyBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1)

- Summary Of "The Political Man" By Seymour Lipset: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESVon EverandSummary Of "The Political Man" By Seymour Lipset: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of A History, Collision of Civilizations and The Valid Prospects of MankindDokument5 SeitenThe End of A History, Collision of Civilizations and The Valid Prospects of MankindLi Su PeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- U1 T7 Reading AssignmentDokument4 SeitenU1 T7 Reading AssignmentIsabelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stasis Before the State: Nine Theses on Agonistic DemocracyVon EverandStasis Before the State: Nine Theses on Agonistic DemocracyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy's Paradox: Populism and its Contemporary CrisisVon EverandDemocracy's Paradox: Populism and its Contemporary CrisisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary Of "The Fascism" By Jover Cervera: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESVon EverandSummary Of "The Fascism" By Jover Cervera: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karl Marx and Other Socialists: Problems of Socialism, the Fall of Communism and a Proper Socialism/EcologyVon EverandKarl Marx and Other Socialists: Problems of Socialism, the Fall of Communism and a Proper Socialism/EcologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Breakthroughs - The Historic Breakthrough by Marx, and the Further Breakthrough with the New Communism, A Basic SummaryVon EverandBreakthroughs - The Historic Breakthrough by Marx, and the Further Breakthrough with the New Communism, A Basic SummaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reconsidering The Economic Thought of Karl Polanyi in 2009Dokument8 SeitenReconsidering The Economic Thought of Karl Polanyi in 2009Pier Paolo Dal MonteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cold War Reckonings: Authoritarianism and the Genres of DecolonizationVon EverandCold War Reckonings: Authoritarianism and the Genres of DecolonizationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy in Modern Europe: A Conceptual HistoryVon EverandDemocracy in Modern Europe: A Conceptual HistoryJussi KurunmäkiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Republic of the Living: Biopolitics and the Critique of Civil SocietyVon EverandThe Republic of the Living: Biopolitics and the Critique of Civil SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allplan 2006 Engineering Tutorial PDFDokument374 SeitenAllplan 2006 Engineering Tutorial PDFEvelin EsthefaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 5 Andhra Pradesh.Dokument18 SeitenUnit 5 Andhra Pradesh.Charu ModiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mounting BearingDokument4 SeitenMounting Bearingoka100% (1)

- Dreamweaver Lure v. Heyne - ComplaintDokument27 SeitenDreamweaver Lure v. Heyne - ComplaintSarah BursteinNoch keine Bewertungen

- (ENG) Visual Logic Robot ProgrammingDokument261 Seiten(ENG) Visual Logic Robot ProgrammingAbel Chaiña Gonzales100% (1)

- 9.admin Rosal Vs ComelecDokument4 Seiten9.admin Rosal Vs Comelecmichelle zatarainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analisa RAB Dan INCOME Videotron TrenggalekDokument2 SeitenAnalisa RAB Dan INCOME Videotron TrenggalekMohammad Bagus SaputroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Installation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemDokument127 SeitenInstallation and User's Guide For AIX Operating SystemPeter KidiavaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Income Tax Calculator 2023Dokument50 SeitenIncome Tax Calculator 2023TARUN PRASADNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J HartneyDokument36 SeitenTest Bank For American Corrections Concepts and Controversies 2nd Edition Barry A Krisberg Susan Marchionna Christopher J Hartneyvaultedsacristya7a11100% (30)

- Jetweigh BrochureDokument7 SeitenJetweigh BrochureYudi ErwantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Testimony 3Dokument14 SeitenBusiness Testimony 3Sapan BanerjeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is.14785.2000 - Coast Down Test PDFDokument12 SeitenIs.14785.2000 - Coast Down Test PDFVenkata NarayanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ML7999A Universal Parallel-Positioning Actuator: FeaturesDokument8 SeitenML7999A Universal Parallel-Positioning Actuator: Featuresfrank torresNoch keine Bewertungen

- (ACYFAR2) Toribio Critique Paper K36.editedDokument12 Seiten(ACYFAR2) Toribio Critique Paper K36.editedHannah Jane ToribioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pilot'S Operating Handbook: Robinson Helicopter CoDokument200 SeitenPilot'S Operating Handbook: Robinson Helicopter CoJoseph BensonNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACM2002D (Display 20x2)Dokument12 SeitenACM2002D (Display 20x2)Marcelo ArtolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gravity Based Foundations For Offshore Wind FarmsDokument121 SeitenGravity Based Foundations For Offshore Wind FarmsBent1988Noch keine Bewertungen

- Codex Standard EnglishDokument4 SeitenCodex Standard EnglishTriyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- EASY DMS ConfigurationDokument6 SeitenEASY DMS ConfigurationRahul KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- White Button Mushroom Cultivation ManualDokument8 SeitenWhite Button Mushroom Cultivation ManualKhurram Ismail100% (4)

- AutoCAD Dinamicki Blokovi Tutorijal PDFDokument18 SeitenAutoCAD Dinamicki Blokovi Tutorijal PDFMilan JovicicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposal IntroductionDokument8 SeitenResearch Proposal IntroductionIsaac OmwengaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of OrganisationDokument9 SeitenThe Role of OrganisationMadhury MosharrofNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net WorthDokument3 SeitenSworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net WorthShelby AntonioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ver Notewin 10Dokument5 SeitenVer Notewin 10Aditya SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Danh Sach Khach Hang VIP Diamond PlazaDokument9 SeitenDanh Sach Khach Hang VIP Diamond PlazaHiệu chuẩn Hiệu chuẩnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Product Guide TrioDokument32 SeitenProduct Guide Triomarcosandia1974Noch keine Bewertungen

- Elliot WaveDokument11 SeitenElliot WavevikramNoch keine Bewertungen

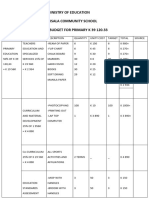

- Ministry of Education Musala SCHDokument5 SeitenMinistry of Education Musala SCHlaonimosesNoch keine Bewertungen