Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Early Insulin TX in t2dm Diabetes Care 2009

Hochgeladen von

Alberto PalaciosOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Early Insulin TX in t2dm Diabetes Care 2009

Hochgeladen von

Alberto PalaciosCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

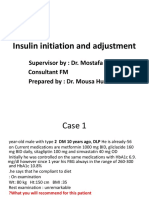

D I A B E T E S P R O G R E S S I O N , P R E V E N T I O N , A N D T R E A T M E N T

Early Insulin Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes

What are the pros?

LUIGI F. MENEGHINI, MD, MBA alike, compared with oral antidiabetic

therapies (11). Patient resistance to the

use of insulin therapy remains a chal-

lenge, especially in populations that may

T

he prevalence of diabetes in the system, were initiated on additional blood

world is growing at an unprece- glucose–lowering treatment only when have misgivings and misconceptions re-

dented rate and rapidly becoming a the mean baseline A1C reached a value of garding the role of insulin replacement in

health concern and burden in both devel- 9.0% (6). Patients started on insulin had diabetes management.

oped and developing countries (1). In ad- an even higher mean A1C of 9.6% and Notwithstanding these issues, there

dition, we are now witnessing an upsurge tended to have more severe baseline com- are specific populations that would

in the incidence of type 2 diabetes in chil- plications and comorbidities than those clearly benefit from early, aggressive, and

dren and adolescents, with the potential started on sulfonylurea, or metformin targeted introduction of insulin therapy.

of translating into a future catastrophic therapy. In addition, the higher the start- For instance, patients presenting with sig-

disease burden as vascular complications ing A1C when therapy was initiated or nificant hyperglycemia may benefit from

of the disease begin affecting a younger changed, the less likely the patient was of timely initiation of insulin therapy that

population. Although there may be con- achieving adequate glycemic control (6). can effectively and rapidly correct their

tention regarding the impact of lowering Although specialists are slightly more metabolic imbalance and reverse the del-

glycemia on macrovascular disease risk, proficient than general practitioners in in- eterious effects of excessive glucose (glu-

there is strong consensus of the definite tensifying diabetes therapy when war- cotoxicity) and lipid (lipotoxicity)

benefits of lowering blood glucose to re- ranted (7), overall clinical inertia results exposure on -cell function and insulin

duce the risk of retinopathy and nephrop- in the majority of patients failing to action (12). In vitro studies have demon-

athy in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes achieve, or maintain, adequate metabolic strated that chronic hyperglycemia leads

(2,3). Despite supporting data and multi- goals from a period of months to several to increased production of reactive oxy-

ple guidelines advanced by professional years (8,9). In summary, to improve these gen species, and subsequent oxidative

organizations, overall glycemic control suboptimal metabolic outcomes, and re- stress, which appears to affect insulin pro-

falls far below expectations (4). Overall, duce the risk of disease-related complica- moter activity (PDX-1 and MafA binding)

⬍36% of individuals with diabetes are at tions, more intensive management of and results in diminished insulin gene ex-

recommended glycemic targets, with the glycemia is warranted, including the op- pression in glucotoxic -cells (13). Inter-

most difficult-to-control cases repre- tion of introducing insulin therapy earlier estingly, in vitro experiments have shown

sented by insulin-deficient individuals on than the current widely practiced sub- that these glucotoxic effects occur in a

insulin therapy to manage their diabetes standard of care. continuum of glucose concentrations (no

(4). Furthermore, as -cell dysfunction clear threshold effect), are reversible with

progresses over time, many patients with INTRODUCTION OF INSULIN reinstitution of euglycemic conditions,

type 2 diabetes, treated with oral agents, EARLIER IN THE TREATMENT and result in the greatest recovery of

fail to achieve or maintain adequate gly- PARADIGM — Typically, whereas -cell function with shorter periods of ex-

cemic control. Unfortunately, in many of introducing insulin therapy in a more posure to hyperglycemia (14). Various

these cases, antiglycemic therapy is not timely fashion would significantly im- studies have demonstrated improvement

adjusted or advanced, thereby exposing prove glycemic control among subjects in insulin sensitivity and -cell function

patients to prolonged hyperglycemia and with type 2 diabetes, the question of in- after correction of hyperglycemia with in-

the increased risk of diabetes-related sulin initiation timing in relation to other tensive insulin therapy (15).

complications. The term “clinical inertia,” antiglycemic therapies is the subject of

which has come to define the lack of ini- considerable debate (10). While insulin

tiation, or intensification of therapy when administration has the potential of INTENSIVE INSULIN

clinically indicated (5), is most pro- achieving the most effective reductions in TREATMENT AND -CELL

nounced in the setting of insulin initia- glycemic control, the initiation of insulin FUNCTION — A number of trials

tion. Subjects with type 2 diabetes, therapy requires greater use of resources, have evaluated the strategy of implement-

managed in a large integrated health care time, and effort from provider and patient ing short-term aggressive insulin replace-

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

ment as first-line therapy in the

management of hyperglycemia in newly

From the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism and the Diabetes Research Institute, Univer-

sity of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida.

diagnosed type 2 diabetes (Table 1), with

Corresponding author: Luigi F. Meneghini, lmeneghi@med.miami.edu. the goal of improving and preserving

The publication of this supplement was made possible in part by unrestricted educational grants from Eli -cell function, reducing insulin resis-

Lilly, Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Generex Biotechnology, Hoffmann-La Roche, Johnson & Johnson, LifeScan, tance, and maintaining optimal glycemic

Medtronic, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, sanofi-aventis, and WorldWIDE. control through disease “remission” (16 –

DOI: 10.2337/dc09-S320

© 2009 by the American Diabetes Association. Readers may use this article as long as the work is properly 18). In these studies, intensive insulin

cited, the use is educational and not for profit, and the work is not altered. See http://creativecommons. therapy was delivered via multiple daily

org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for details. insulin injections, or insulin pump ther-

S266 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 32, SUPPLEMENT 2, NOVEMBER 2009 care.diabetesjournals.org

Meneghini

Table 1—Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients with type 2 diabetes receiving temporary insulin therapy at disease diagnosis

Duration

Baseline Insulin dose Days to insulin

A1C (units 䡠 kg⫺1 䡠 glycemic therapy % Early % Sustained

n Age BMI (%) day⫺1) control (weeks) responders responders Weight change

Ilkova et al. (17) 13 50 27 11.2 0.61 1.9 2 92 69 (26 months) 0.4 kg

Li et al. (16) 126 50 25 10.0 0.7 6.3 2 90 42 (24 months) ⫺0.04 kg/m2

Ryan et al. (18) 16 52 31 11.8 0.37–0.73 ⬍14 2–3 88 44 (12 months) ⫺0.5 kg/m2

Early responders are subjects who achieved euglycemia with insulin treatment, and late responders are subjects who maintained long-term euglycemia without

pharmacotherapy after the initial insulin treatment.

apy (continuous subcutaneous insulin in- tion over time. The recently published A within an average of 8 days from start of

fusion), over a period of 2–3 weeks, with Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial therapy (Table 2). Treatment was with-

achievement of euglycemia in ⬃90% of (ADOPT) demonstrated longer mainte- drawn after 2 weeks of normoglycemia,

subjects on completion of insulin treat- nance of glycemic control in patients us- followed by diet and exercise manage-

ment. After insulin withdrawal, patients ing a thiazolidinedione (rosiglitazone) ment. A greater proportion of patients

were maintained on diet therapy only, compared with glyburide or metformin randomized to intensive insulin therapy

with 42– 69% maintaining euglycemia 12 monotherapy, although -cell function, achieved glycemic targets and did so in a

or more months after treatment. Patients as measured by HOMA-B was no different shorter period compared with oral agent

who achieved and maintained long-term at the end of the trial between the rosigli- therapy (Table 2). Shortly after discon-

euglycemia tended to have a better re- tazone and sulfonylurea groups (20); the tinuing antiglycemic treatment, measures

sponse to insulin therapy, as well as asso- benefits in durability of control seemed to of first-phase insulin release, HOMA-B

ciated improvements in -cell function, have been a result of improved insulin and HOMA-IR were similar among all

including first-phase insulin release, as sensitivity. treatment groups. By the end of 1 year,

measured by homeostasis model assess- A recent study comparing intensive remission rates were significantly higher

ment of -cell function (HOMA-B) and insulin therapy (multiple daily insulin in- in the groups that had received initial in-

intravenous glucose tolerance tests. jections or continuous subcutaneous in- sulin therapy (51 and 45% in the contin-

Improvements in -cell function and sulin infusion) with oral hypoglycemic uous subcutaneous insulin infusion and

insulin action have also been reported agents (glicazide and/or metformin) in multiple daily insulin injections groups,

when euglycemia is achieved with nonin- newly diagnosed patients with type 2 di- respectively), compared with 27% in the

sulin therapies (19). Unfortunately, as il- abetes provided some provocative results oral therapy group. Whereas in the oral

lustrated by the U.K. Prospective Diabetes (21). In this trial, 92% of 382 subjects agent group, acute insulin response at 1

Study, long-term glycemic control in type with poorly controlled diabetes achieved year declined significantly compared with

2 diabetes is difficult to maintain, regard- glycemic targets (fasting and 2-h post- immediate post-treatment, it was main-

less of the therapeutic intervention due, prandial capillary glucose levels of ⬍110 tained in the insulin treatment groups. Of

in part, to progressive loss of -cell func- mg/dl and ⬍144 mg/dl, respectively) note, responders typically had higher

BMI, less baseline hyperglycemia, and

greater responsiveness to therapy than

Table 2—Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes comparing subjects treated with in-

nonresponders.

sulin or oral agent therapies lasting for 2 weeks after achievement of normoglycemia

Another study comparing early and

continued insulin treatment versus oral

Continuous Multiple agent therapy (glibenclamide) over a pe-

subcutaneous insulin daily riod of 2 years in recently diagnosed pa-

infusion injections Oral agents tients with type 2 diabetes showed better

long-term glycemic control and -cell

n 133 118 101

function in the insulin-treated group

Age (yrs) 50 51 52

(22). There was no difference in weight

BMI (kg/m2) 25 24 25

gain between insulin and oral agent ther-

Baseline A1C (%) 9.8 9.7 9.5

apy and no reported cases of severe hypo-

% Achieving euglycemia 97 95 83

glycemia, reflecting easier-to-manage

Time to euglycemia (days) 4 5.6 9.3

glycemia, probably as a result of better

Daily drug doses 0.68 units/kg (mean) 0.74 units/kg Glicazide 160 mg ⫹

endogenous insulin production.

(mean) metformin 1,500 mg

(max median)

⌬ in AIR* POTENTIAL

(pmol 䡠 l⫺1 䡠 min⫺1) 951 800 831 PHYSIOLOGICAL EFFECTS

AIR (median) in remission OF INSULIN REPLACEMENT

groups at 1 year 809 729 335† THERAPY — What could account for

From Weng et al. (21). *Change in median AIR (acute insulin response) between baseline and treatment end. some of the differences in -cell function

†P ⬍ 0.05 compared with continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion. seen in studies with early aggressive insu-

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 32, SUPPLEMENT 2, NOVEMBER 2009 S267

Early insulin treatment in type 2 diabetes

lin therapy? A study evaluating the anti- but with less weight gain, and hypoglyce- No other potential conflicts of interest rele-

inflammatory effects of an insulin mia risk than basal/prandial or mixed in- vant to this article were reported.

infusion on obese subjects without diabe- sulin strategies, when baseline A1C is

tes demonstrated suppression of nuclear ⱕ8.5% (27). Thus, in a patient whose

factor B. Nuclear factor B is the key predominant glycemic burden occurs References

transcription factor responsible for the overnight and whose A1C level is within 1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King

H. Global prevalence of diabetes: esti-

transcription of proinflammatory cyto- 1–2% points of target, starting with a low mates for the year 2000 and projections

kines, adhesion molecules and enzymes dose of basal insulin (0.2 units 䡠 kg⫺1 䡠 for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1047–

responsible for producing reactive oxy- day⫺1) and adjusting the dose to achieve 1053

gen species (23). As a consequence, insu- fasting blood glucose levels ⬍110 –130 2. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial

lin infusion significantly suppressed mg/dl often proves an effective strategy. Research Group. The effect of intensive

generation of reactive oxygen species and With higher A1C levels, replacing pran- treatment of diabetes on the development

decreased concentrations of plasma solu- dial insulin, with or without basal insulin and progression of long-term complica-

ble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sI- coverage, results in greater A1C reduction tions in insulin-dependent diabetes mel-

CAM-1), monocyte chemo-attractant than basal-only replacement, albeit at the litus. N Engl J Med 1993;329:977–986

protein-1 (MCP-1), and plasminogen ac- expense of more weight gain and hypo- 3. UKPDS Group. Intensive blood-glucose

control with sulphonylureas or insulin

tivator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), among other glycemia (28). For example, patients in- compared with conventional treatment

observed anti-inflammatory actions (24). adequately controlled on basal insulin and risk of complications in patients with

Could the timing of the intervention can be started on one or more doses of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;

affect the metabolic response to insulin rapid-acting insulin (0.05 units/kg/meal) 352:837– 853

therapy? For example, loss of first-phase before one or more meals (usually the 4. Koro CE, Bowlin SJ, Bourgeois N, Fedder

insulin response, possibly as a conse- largest meals), and the insulin dose ti- DO. Glycemic control from 1988 to 2000

quence of glucotoxicity, is evident with trated to achieve postprandial blood glu- among U.S. adults diagnosed with type 2

fasting plasma glucose concentrations cose levels ⬍180 mg/dl. A basal/bolus diabetes: a preliminary report. Diabetes

⬎115 mg/dl (25). Often, when diabetes is insulin replacement, giving patients flex- Care 2004;27:17–20

diagnosed, fasting plasma glucose levels ible prandial dosing instructions, as op- 5. Phillips LS, Branch WT, Cook CB, Doyle

JP, El-Kebbi IM, Gallina DL, Miller CD,

are usually significantly higher, and may posed to fixed doses of premeal insulin, Ziemer DC, Barnes CS. Clinical inertia.

have been so for quite some time (26), has been shown to be associated with Ann Intern Med 2001;135:825– 834

exposing -cells to chronic hyperglyce- equivalent glycemic control, but with less 6. Karter AJ, Moffet HH, Liu J, Parker MM,

mia and consequent -cell decompensa- weight gain (29). Furthermore, the use of Ahmed AT, Go AS, Selby JV. Glycemic

tion (13). It could be hypothesized that basal insulin analogs (glargine or detemir) response to newly initiated diabetes ther-

early aggressive physiologic insulin re- is associated with less hypoglycemia (es- apies. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:598 –

placement with both prandial and basal pecially nocturnal hypoglycemia) and, in 606

coverage results in rapid improvement in the case of insulin detemir, less weight 7. Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A, Zinman B,

glucolipotoxicity, reduction of the in- gain than human NPH insulin (27,30). van Walraven C. Clinical inertia in re-

flammatory milieu, and consequent sponse to inadequate glycemic control:

do specialists differ from primary care

greater preservation of -cell function.

CONCLUSIONS — In summary, ag- physicians? Diabetes Care 2005;28:600-

Some of these improvements in -cell 606

gressive and often temporary use of insu-

function were also evident after rigor- 8. Rubino A, McQuay LJ, Gough SC, Kvasz

lin therapy at disease onset in type 2

ous management with glyburide and M, Tennis P. Delayed initiation of subcu-

diabetes is associated with effective glyce-

metformin. taneous insulin therapy after failure of

mic control with minimal weight gain and

oral glucose-lowering agents in patients

hypoglycemia. Early restitution of physi-

INSULIN REPLACEMENT with type 2 diabetes: a population-based

ologic insulin secretion and glycemic con- analysis in the UK. Diabet Med 2007;24:

OPTIONS AND STRATEGIES —

trol could be, in theory, followed by 1412–1418

Whereas the use of insulin therapy in

therapies to prolong maintenance of eug- 9. Grant RW, Cagliero E, Dubey AK, Gildes-

newly diagnosed subjects with type 2 di-

lycemia, such as thiazolidinediones- (20) Game C, Chueh HC, Barry MJ, Singer DE,

abetes appears to be associated with a low Nathan DM, Meigs JB. Clinical inertia in

or glucagons-like peptide 1– based inter-

risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain, the the management of type 2 diabetes meta-

ventions (to date not clinically tested). A

use of algorithm-driven insulin replace- bolic risk factors. Diabet Med 2004;21:

more timely and selective introduction of

ment in more advanced disease is often 150 –155

insulin replacement therapy, as -cell

associated with a greater incidence of 10. Goldberg RB, Holman R, Drucker DJ.

function progresses, could facilitate the

weight gain and hypoglycemia. Individu- Management of type 2 diabetes. N Engl

achievement and maintenance of euglyce- J Med 2008;358:293–297

alizing the insulin prescription may min-

mia and thus reduce disease-associated 11. Davidson MB. Early insulin therapy for

imize some of these adverse outcomes.

complications. type 2 diabetic patients: more cost than

Using the A1C status of a patient, the fast-

ing blood glucose, and if available, the benefit. Diabetes Care 2005;28:222–224

12. Unger RH, Grundy S. Hyperglycemia as

postprandial glucose could assist the pro- Acknowledgments — L.F.M. has received an inducer as well as a consequence of

vider in individualizing insulin replace- grant support from sanofi-aventis, Novo Nor- impaired islet cell function and insulin re-

ment. Published trials in suboptimally disk, Hoffmann-La Roche, and Medtronic; sistance: implications for the manage-

controlled insulin-naive type 2 diabetes consulting fees from Novo Nordisk and NIPRO; ment of diabetes. Diabetologia 1985;28:

seem to indicate that basal insulin re- and speaker’s fees from sanofi-aventis, Eli Lilly, 119 –121

placement yields similar effectiveness, Merck, and Amylin. 13. Poitout V, Robertson RP. Glucolipotoxic-

S268 DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 32, SUPPLEMENT 2, NOVEMBER 2009 care.diabetesjournals.org

Meneghini

ity: fuel excess and beta-cell dysfunction. Lachin JM, O’Neill MC, Zinman B, Viberti Porte D Jr: Relationships between fasting

Endocr Rev 2008;29;351–366 G, ADOPT Study Group. Glycemic dura- plasma glucose levels and insulin secre-

14. Gleason CE, Gonzalez M, Harmon JS, bility of rosiglitazone, metformin, or gly- tion during intravenous glucose tolerance

Robertson RP. Determinants of glucose buride monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976;42:

toxicity and its reversibility in the pancre- 355:2427–2443 222–229

atic islet beta-cell line, HIT-T15. Am J 21. Weng J, Li Y, Xu W, Shi L, Zhang Q, Zhu 26. Samuels TA, Cohen D, Brancati FL,

Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2000;279: D, Hu Y, Zhou Z, Yan X, Tian H, Ran X, Coresh J, Kao WH. Delayed diagnosis of

E997–E1002 Luo Z, Xian J, Yan L, Li F, Zeng L, Chen Y, incident type 2 diabetes mellitus in the

15. Garvey WT, Olefsky JM, Griffin J, Ham- Yang L, Yan S, Liu J, Li M, Fu Z, Cheng H. ARIC study. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:

man RF, Kolterman OG. The effect of in- Effect of intensive insulin therapy on beta- 717–724

sulin treatment on insulin secretion and cell function and glycaemic control in pa- 27. Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, Gerich J. The

insulin action in type II diabetes mellitus. tients with newly diagnosed type 2 treat-to-target trial: randomized addition

Diabetes 1985;34:222–234 diabetes: a multicentre randomised paral- of glargine or human NPH insulin to oral

16. Li Y, Xu W, Liao Z, Yao B, Chen X, Huang lel-group trial. Lancet 2008;371:1753- therapy of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabe-

Z, Hu G, Weng J. Induction of long-term 1760 tes Care 2003;26:3080 –3086

glycemic control in newly diagnosed type 22. Alvarsson M, Sundkvist G, Lager I, Hen- 28. Holman RR, Thorne KI, Farmer AJ, Da-

2 diabetic patients is associated with im- ricson M, Berntorp K, Fernqvist-Forbes E, vies MJ, Keenan JF, Paul S, Levy JC. 4-T

provement of beta-cell function. Diabetes Steen L, Westermark G, Westermark P, Study Group: Addition of biphasic, pran-

Care 2004;27:2597–2602 Orn T, Grill V. Beneficial effects of insulin dial, or basal insulin to oral therapy in

17. Ilkova H, Glaser B, Tunçkale A, Bagriaçik versus sulphonylurea on insulin secretion type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2007;357:

N, Cerasi E. Induction of long-term gly- and metabolic control in recently diag- 1716 –1730

cemic control in newly diagnosed type 2 nosed type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes 29. Bergenstal RM, Johnson ML, Powers MA,

diabetic patients by transient intensive in- Care 2003;26:2231–2237 Wynne A, Vlajnic A, Hollander PA. Using

sulin treatment. Diabetes Care 1997;20: 23. Dandona P, Aljada A, Mohanty P, Ghanim a simple algorithm (ALG) to adjust meal-

1353–1356 H, Hamouda W, Assian E, Ahmad S. In- time glulisine (GLU) based on pre-pran-

18. Ryan EA, Imes S, Wallace C. Short-term sulin inhibits intranuclear factor kB and dial glucose patterns is a safe and effective

intensive insulin therapy in newly diag- stimulates IkB in mononuclear cells in alternative to carbohydrate counting

nosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care obese subjects: evidence for an anti-in- (Carb Count) (Abstract). Diabetes 2006;

2004;27:1028 –1032 fammatory effect? J Clin Endocrinol 55 (Suppl. 1):A105

19. Peters AL, Davidson MB. Maximal dose Metab 2001;86:3257–3265 30. Philis-Tsimikas A, Charpentier G, Clau-

glyburide therapy in markedly symptom- 24. Dandona P, Chaudhuri A, Mohanty P, son P, Ravn GM, Roberts VL, Thorsteins-

atic patients with type 2 diabetes: a new Ghanim H. Anti-inflammatory effects on son B. Comparison of once-daily insulin

use for an old friend. J Clin Endocrinol insulin. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metabol detemir with NPH insulin added to a reg-

Metab 1996;81:2423–2427 Care 2007;10:511–517 imen of oral antidiabetic drugs in poorly

20. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, Herman 25. Brunzell JD, Robertson RP, Lerner RL, controlled type 2 diabetes. Clin Ther

WH, Holman RR, Jones NP, Kravitz BG, Hazzard WR, Ensinck JW, Bierman EL, 2006;28:1569 –1581

care.diabetesjournals.org DIABETES CARE, VOLUME 32, SUPPLEMENT 2, NOVEMBER 2009 S269

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hipoglikemi Diagnosa Dan TalakDokument19 SeitenHipoglikemi Diagnosa Dan TalakPediatri 78 UndipNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- 1.16 Evaluation of Hypoglycemic Effect of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (Banaba) Leaf Extract in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RabbitsDokument6 Seiten1.16 Evaluation of Hypoglycemic Effect of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (Banaba) Leaf Extract in Alloxan Induced Diabetic RabbitsNikole PetersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- International Journal of Diabetes and Clinical Research Ijdcr 7 128Dokument7 SeitenInternational Journal of Diabetes and Clinical Research Ijdcr 7 128Yaseen MohamnadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Egregious Eleven of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - My Endo ConsultDokument20 SeitenEgregious Eleven of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - My Endo Consultakbar011512Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- What Is Diabete1Dokument134 SeitenWhat Is Diabete1Icha AjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Effects of Advanced Carbohydrate Counting On Glucose Control and QolDokument9 SeitenEffects of Advanced Carbohydrate Counting On Glucose Control and QollloplNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Diagnosis and Management of Atypical Types of Diabetes: Kathryn Evans Kreider, DNP, FNP-BCDokument7 SeitenThe Diagnosis and Management of Atypical Types of Diabetes: Kathryn Evans Kreider, DNP, FNP-BCromyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Endocrinology QuestionsDokument3 SeitenEndocrinology Questionstoby hojojhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- DC 23 in 01Dokument7 SeitenDC 23 in 01Arturo Eduardo Huarcaya OntiverosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- Pharmaceutical Care in Dm. Apoteker UbayaDokument48 SeitenPharmaceutical Care in Dm. Apoteker UbayaViona PrasetyoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.1 What Is Diabetes UrduDokument7 Seiten1.1 What Is Diabetes UrduMudassir AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- AGP Report: Glucose Statistics and Targets Time in RangesDokument14 SeitenAGP Report: Glucose Statistics and Targets Time in RangesLeona LickNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Insulin Initiation PPT - PPTX 2Dokument53 SeitenInsulin Initiation PPT - PPTX 2Meno Ali100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- RTD Insulin 101017Dokument60 SeitenRTD Insulin 101017Baskoro Tri LaksonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- HbA1c Person Leaflet 0509Dokument2 SeitenHbA1c Person Leaflet 0509ppeterarmstrongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Gestational DiabetesDokument21 SeitenGestational DiabetesRiko Sampurna SimatupangNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A Normal Blood Sugar LevelDokument3 SeitenWhat Is A Normal Blood Sugar LevelexpertjatakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prediabetes - OKE - IDI LMGNDokument48 SeitenPrediabetes - OKE - IDI LMGNruthmindosiahaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diabetes TutorialDokument3 SeitenDiabetes TutorialmorsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Adknowl: Audit of Diabetes KnowledgeDokument2 SeitenThe Adknowl: Audit of Diabetes Knowledgebich truongNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Awareness of Diabetic Children Care Givers About Complications of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Dhahran, Saudi ArabiaDokument7 SeitenAwareness of Diabetic Children Care Givers About Complications of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus in Dhahran, Saudi ArabiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- 1 DMDokument49 Seiten1 DMDrMohammad KhadrawyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Padron Nominal DM 2016Dokument215 SeitenPadron Nominal DM 2016Pablo Jhonatan Hernandez RamosNoch keine Bewertungen

- High Blood Sugar Levels Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Evaluation.Dokument3 SeitenHigh Blood Sugar Levels Hyperglycemia. Diabetes Evaluation.Ibn SadiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Diabetes: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDokument33 SeitenDiabetes: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchkamleshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ryzodeg Experience in Action (REAXN) Presenter Slides.2018Dokument9 SeitenRyzodeg Experience in Action (REAXN) Presenter Slides.2018Jenny Calapati TorrijosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Komplikasi Diabetes (Akut Dan Kronik) : Luh Gede Sri YennyDokument50 SeitenKomplikasi Diabetes (Akut Dan Kronik) : Luh Gede Sri YennyArya WinataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blood Glucose MonitoringDokument20 SeitenBlood Glucose Monitoringask1400100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Should Ultra-Rapid Acting Analogs Be The New Standard of Mealtime Insulins Care?Dokument51 SeitenShould Ultra-Rapid Acting Analogs Be The New Standard of Mealtime Insulins Care?Oscar CastañonNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Legacy Effect of Early Intensive Glycemic ControlDokument9 SeitenThe Legacy Effect of Early Intensive Glycemic ControlSouradipta GangulyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)