Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Beneficiality-Te Chi

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa May GaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Beneficiality-Te Chi

Hochgeladen von

Vanessa May GaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Instituting good water governance including responsive policy and institutional arrangements,

appropriate planning, and effective implementation are the keys in addressing the artificial water

crisis in the Philippines.

Your honors, Bukidnon State University presents its cost-benefit analysis and submits that it is

high time to create a Department of Waters and Resources as the chief overseer and sole

regulator of water distribution in the country.

First point, with regulatory functions controlled by so many different agencies, enforcement

becomes difficult, especially when mandates and accountabilities overlap.

Second point, water stability is equitable to economic prosperity.

On the first analysis, although the National Water Resources Board (NWRB) is designated

under the Water Code of the Philippines as chief overseer of water resources management in

the country, NWRB actually shares, if not competes for, its ostensibly all-encompassing

mandate with more than 30 other government offices and corporations that all deal with either

water supply, irrigation, hydropower, flood control, water management or other water-related

concerns. For instance, the mandate of watershed conservation is with the Department of

Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), domestic water supply is with the Local Water

Utilities Administration (LWUA), irrigation water supply is with the National Irrigation

Administration (NIA), and flood control management is with the Department of Public Works and

Highways (DPWH). This becomes very problematic because the sheer number of potential

actors and the assumed plurality of mandates (no mandate is deemed a priority over the others)

make for serious political inertia in terms of getting the job done. Whereas, if we pave way to the

creation of a Department, there will be a central regulatory structure which would provide

coherence in its mandates unlike the present menagerie of laws which led to the current weak

and fragmented institutional and regulatory framework in the water resources sector. The

absence of an integrated water resources management that adopts a holistic approach to water

sector demands will be better addressed under our proposal.

On the second analysis, the country’s water problem is actually ironic, because the country has

enough freshwater resources, rainfall, surface water and groundwater to meet the requirements

of the country’s ever-increasing population and rapid urbanization and industrialization. In the

status quo, NWRB is housed at the Department of Environment and Natural Resources

(DENR). Being a central agency of 120 people only has Php 143M pesos as budget with limited

capacities for water resources management. It is even more astonishing that the total budget of

P651,981,000 million for the Philippine Carabao Center is 4 times more than that of the NWRB

budget. The lean institutional set-up constrains the agency to act on its implementing regulatory

laws which remains a challenge. It is apparent that NWRB suffers from underfunding from the

national government, which limits its ability to hire experts, obtain complete data for planning

and management, and to regularly monitor water resources and water resource activities at the

local and national levels. Wherefore, it must be stressed that the Philippine government’s

responsibility to safe, clean, and accessible drinking water, sanitation and irrigation services to

the public are of utmost importance, and it is attainable through well-coordinated, effective,

efficient and sustainable management of its water and sanitation resources.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Labor Relations Final Exam 2020Dokument9 SeitenLabor Relations Final Exam 2020Vanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Plumbing DesignDokument60 SeitenFundamentals of Plumbing DesignBianca MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Waste Stabilization PondsDokument44 Seiten4 Waste Stabilization PondsEgana Isaac100% (1)

- (Theory and Applications of Transport in Porous Media 32) Viliam Novák, Hana Hlaváčiková - Applied Soil Hydrology-Springer International Publishing (2019) PDFDokument354 Seiten(Theory and Applications of Transport in Porous Media 32) Viliam Novák, Hana Hlaváčiková - Applied Soil Hydrology-Springer International Publishing (2019) PDFshahid ali100% (1)

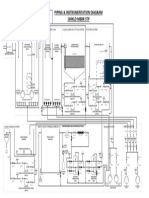

- P&id - 100kld MBBR STPDokument1 SeiteP&id - 100kld MBBR STPRabindra SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Storage Reservior and Balancing ReservoirDokument19 SeitenStorage Reservior and Balancing ReservoirNeel Kurrey0% (1)

- Water Quality Surveillance Power PointDokument44 SeitenWater Quality Surveillance Power PointBobby MuyundaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Principles of Sanitary/Plumbing Design: Engineering Utilities IiDokument22 SeitenBasic Principles of Sanitary/Plumbing Design: Engineering Utilities IiKarl Cristian DaquilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Low Cost Treatments PDFDokument55 SeitenLow Cost Treatments PDFDrShrikant JahagirdarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Purified Water System ValidationDokument2 SeitenPurified Water System Validationankur_haldarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Relations Final Exam 2020Dokument6 SeitenLabor Relations Final Exam 2020Vanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- APES Notes - Chapter 17: Water Pollution and Its PreventionDokument11 SeitenAPES Notes - Chapter 17: Water Pollution and Its Preventionirregularflowers100% (1)

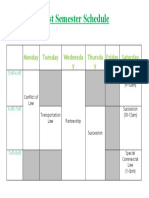

- First Semester ScheduleDokument1 SeiteFirst Semester ScheduleVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partnership 2020 SyllabusDokument6 SeitenPartnership 2020 SyllabusVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus SuccessionDokument1 SeiteSyllabus SuccessionVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Saudi Arabia Airlines Vs CADokument1 Seite5 Saudi Arabia Airlines Vs CAVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rules On ManagementDokument2 SeitenRules On ManagementVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A. Rules On Division of Profit & LossDokument2 SeitenA. Rules On Division of Profit & LossVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- After Mock Debate PointsDokument1 SeiteAfter Mock Debate PointsVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semester TitleDokument1 SeiteSemester TitleVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banks On Second-Endorsed Checks Accept or Not?Dokument3 SeitenBanks On Second-Endorsed Checks Accept or Not?Vanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument24 SeitenCase DigestVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIBRT: Online Lending Should Be Regulated by The Bangko Sentral NG Pilipinas Governing LawsDokument2 SeitenLIBRT: Online Lending Should Be Regulated by The Bangko Sentral NG Pilipinas Governing LawsVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro - Case DigestsDokument8 SeitenCiv Pro - Case DigestsVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample ExamDokument1 SeiteSample ExamVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Pro - Digests (Rule 14)Dokument2 SeitenCiv Pro - Digests (Rule 14)Vanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument24 SeitenCase DigestVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample ExamDokument1 SeiteSample ExamVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bukidnon State University Malaybalay CityDokument1 SeiteBukidnon State University Malaybalay CityVanessa May GaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hydrology-Case StudyDokument4 SeitenHydrology-Case StudyPetForest Ni JohannNoch keine Bewertungen

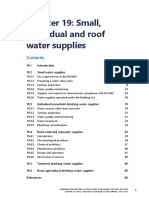

- Drinking-Water Guidelines - Chapter 19 Small Individual and Roof Water SuppliesDokument57 SeitenDrinking-Water Guidelines - Chapter 19 Small Individual and Roof Water SuppliesMohamed KhalifaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 100 TOP WATER SUPPLY Engineering Objective Questions and Answers WATER SUPPLY Engineering Mcqs PDFDokument8 Seiten100 TOP WATER SUPPLY Engineering Objective Questions and Answers WATER SUPPLY Engineering Mcqs PDFMV chandan50% (2)

- Pat Kelas Xi Genap 22Dokument3 SeitenPat Kelas Xi Genap 22Ricardo ParlindunganNoch keine Bewertungen

- LP A Rivers Tale 1Dokument3 SeitenLP A Rivers Tale 1Pramsu ShauryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LinhNTN-WasteWater Management From The Practice of Hanoi Urban SectorDokument27 SeitenLinhNTN-WasteWater Management From The Practice of Hanoi Urban SectorLinh Linh Bất TửNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chesapeake Bay Report CardDokument6 SeitenChesapeake Bay Report CardWAMU885newsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 2Dokument79 SeitenChapter 2Kc Kirsten Kimberly MalbunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drainage Systems and Water Resource of Ethiopia and The HornDokument13 SeitenDrainage Systems and Water Resource of Ethiopia and The HornWendimu GirmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendix 41 - Roy Hill Mine Water Management PlanDokument28 SeitenAppendix 41 - Roy Hill Mine Water Management PlanFrancisco HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tender Documents For Mandira Small Hydro Electric Project (10Mw), Odisha Volume-3 of 4Dokument81 SeitenTender Documents For Mandira Small Hydro Electric Project (10Mw), Odisha Volume-3 of 4nira365100% (1)

- HEC-HMS Application Sri Lanka Devanmini and Najim 2013Dokument8 SeitenHEC-HMS Application Sri Lanka Devanmini and Najim 2013Macklera MrutuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fisa Comparatie FreonDokument2 SeitenFisa Comparatie FreoncristiangodeanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Sector in Dili Timor Leste - Field StudyDokument14 SeitenWater Sector in Dili Timor Leste - Field StudyGaspar Da Costa XimenesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ce 405: Environmental Engineering-I: Important QuestionsDokument4 SeitenCe 405: Environmental Engineering-I: Important QuestionsVahid AbdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Household Water Filtration System For Rural AreasDokument3 SeitenHousehold Water Filtration System For Rural AreasJonathan Llewellyn AndradaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water A Precious Resource Revision WorksheetDokument4 SeitenWater A Precious Resource Revision WorksheetDamini PathakNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temtem TypeDokument3 SeitenTemtem TypeCharityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanitary Permit: Office of The Building OfficialDokument2 SeitenSanitary Permit: Office of The Building Officialhje421Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bohol Water and Sanitation Project - PPP CenterDokument8 SeitenBohol Water and Sanitation Project - PPP CenterFaux LexieNoch keine Bewertungen