Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

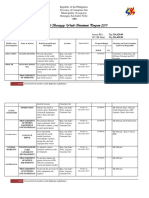

Entiepreneurd Budgeting:: An Emerging Reform?

Hochgeladen von

sehry101Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Entiepreneurd Budgeting:: An Emerging Reform?

Hochgeladen von

sehry101Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

In a widely cited article; Aaron Wildavsky offered an

answer to the question of "why the traditional budget

lasts" (1978). He argued that despite all the efforts to

Entiepreneurd Budgeting: An reform budgeting in the past few decades, it has

remained essentially incremental and line-item.

Emerging Reform? Although this may be true, efforts to reform budgeting

occur with such regularity that the question could easily

be turned around: Why are attacks on traditional bud-

geting so persistent? Some shortcomings must exist in

Dan A. Cothran, Northern Arizona University budgeting for reforms to be proposed so regularly.

Although none of these efforts, such as performance,

program, or zero-base budgeting, entirely supplanted

What influence has entrepreneurial budgeting had on incremental line-item budgeting, elements of these

budget reform? Dan Cothran examines three neiw reforms endure in the budgeting process of many gov-

approaches to budgeting that use decentralization in ernments. Now a new challenge to traditional budget-

an effort to stimulate entrepreneurial behavior by public ing has appeared.

administrators. One method is used by some local gov- The process of government budgeting has changed

ernments in the United States, the second is used by the significantly in the 20th century, beginning with the

national governments of several industrial democracies, introduction of executive budgeting in the 1920s. Since

and the third isproposed as a way to improve U.S. the 1 9 5 0 ~a ~relatively major reform has been proposed

defense budgeting. Afer toppolicy makers have estab- about once each decade in an effort to overcome some

lished their overall control through broad guidelines, of the perceived deficiencies of incremental line-item

states the author, the new methods decentralize actual budgeting-performance budgeting in the 1 9 5 0 ~pro- ~

management decisions much as a market does by pro- gram budgeting in the 1 9 6 0 ~and ~ zero-base budgeting

viding agency managers with incentives to be both effi- in the 1970s. In the 1 9 8 0 ~there

~ was a growth of what

cient and effective. In addition, the new methods aim might be called "automatic control budgeting" in which

voters and policy makers tried to impose statutorily

to make administrators more accountable for the results

prescribed formulas on revenues and expenditures, the

of their decisions by monitoring actual performance

most notable examples being Proposition 13-type laws,

more than in thepast.

Gram-Rudman-Hollings, and the movement for a fed-

eral balanced budget amendment to the Constitution.1

In the 1990s, another type of budgetary reform is being

proposed-entrepreneurial budgeting. In this article, I

examine three examples of this type of budgeting. One

is used by some local U.S. governments, another by the

national governments of several industrial democracies,

and the third is proposed as a way to improve defense

budgeting in the United States. This article asks

whether these methods have any qualities in common,

why they are being proposed, and how likely they are

to last. As disparate as they appear, they are remark-

ably similar in fundamental ways. Although they go by

various names, all of these methods might be character-

ized as entrepreneurial budgeting because of their

emphasis on decentralization and incentives.

Public Administration Review + Septernber/October 1993, Vol. 53, No. 5

Entrepreneurial Budgeting: Three

Examples

I Basing their actions on o~aniratbnaltheory!

I

policy m a h h o p that operating

Expenditure Control Budgeting2

One observer claims that since 1977, U.S. "cities have been managen will exhibitgreaterproductiuity in return

experimenting with and slowly developing a new system for

public budgeting" (Gaebler Group, 1988, p. I), which has been for the greaterfreedom.

called entrepreneurial budgeting, expenditure control budget-

ing, profit sharing, and various other things. Unlike tradition- frequently attributed to government bureaucracy and moves

al budgeting where policy makers wait for departments to toward the flexibility often associated with private enterprise.

make their requests, in this approach the city council begins That is why it is sometimes called entrepreneurial budgeting.

by setting expenditure limits. This part of the budgetary pro-

cess is very much top-down, rather than bottom-up as is often Basing their actions on organizational theory, policy mak-

the case under traditional budgeting. The expenditure limits ers hope that operating managers will exhibit greater produc-

are frequently expressed by a formula, such as holding the tivity in return for the greater freedom. Carl Bellone examined

increase in total spending to 7 percent over the current year. four cities in California that used decentralized budgeting. He

The council's budget plan is quite brief, perhaps no more than writes: "Instead of the department heads in each city submit-

two pages, in contrast to the huge line-item document with ting a detailed budget request which is then negotiated item

which most city councils have traditionally struggled. The by item with the city manager ...each department is given a pot

idea is to get the top policy makers to focus on the big pic- of money .... The department head is then free to spend the

ture, not the details. In doing this, the council tries to deter- money allocated in the way that he or she feels is best."

mine what citizens want their city government to do. From Bellone concludes, "This budgetary freedom fosters creativity

this information and their own preferences, the council mem- and innovation" (1988, p. 84).

bers set the,overall policy direction for the city. They may, for One of the earliest local governments to use the approach

example, decide that the citizens are particularly concerned was the city of Fairfield, California. The city manager intro-

about the conditions of roads, and hence the city council may duced the system after Proposition 13 devastated the city bud-

increase the road budget by 12 percent, rather than only 7 get in 1978. It is a departure from the traditional way of build-

percent. The council then monitors the performance of the ing budgets from the bottom up, in which departments start

city government to ensure that policy goals are being met. It with their expenditure levels for the current year and then try

does not, however, get caught up in detailed scrutiny of line- to increase that as much as possible for the following year,

item spending. In this way, the council, and to an extent the meanwhile quickly spending any balance left over at the end

city manager, move away from micro-management and toward of the fiscal year. In expenditure control budgeting, the

greater attention to broad policy questions. Governments that Farfield city council examines a twopage budget proposal that

use this approach clearly are motivated by the constraints that highlights broad categories of spending. Department heads

voters have put on revenues since the late 1970s. are, in effect, given block grants that demonstrate considerable

At the same time, the operating departments are given trust in their judgment about the use of money and that allow a

more discretion. Within the bounds of the centrally deter- high level of autonomy in managing their departments. Any

mined expenditure limits, each department is free to use funds unspent balance at the end of the fiscal year is retained by the

as its professional managers think best (subject to the usual departments, so that managers have an incentive to save

constraints of legality and political prudence, of course). For unspent funds for higher priority items in the new fiscal year,

example, they are free to move money from salaries to sup- rather than spend the funds immediately for lower priority

plies if they think that will allow their department to pursue its items. Under this system, however, the city council and city

mission more effectively. In addition, the city manager main- manager will expect evidence of achievement by the various

tains a contingency fund for the entire government, so that programs. In fact, by reducing the amount of time that they

individual departments do not need to maintain such funds. spend examining detailed line-items, they will have more time

to monitor actual program performance. This approach greatly

Perhaps the most significant change in this approach is simplifies budget preparation, as departments are generally

what happens to funds left over at the end of the fiscal year. given a lump-sum allocation based on the prior year's budget

Instead of a year-end spending spree motivated by the "use it plus an increment for inflation and for the increase in popula-

or lose it" rule, departments are allowed to carry over a signifi- tion.3 In 1982, the Fairfield city manager received the

cant portion of their unspent authority, usually 30 to 50 per- International City Managers Association ward for Outstanding

cent, but in some cases 100 percent. This form of "profit shar- Management Innovation for the new approach. Fairfield ofi-

ing" is seen by many as the most important departure from the cials believe that the approach saved the city almost $5 million

traditional budget. Along with the general increase in discre- over a period of 8 years (Cal-Tm News, June 1, 1987, p. 10).

tion over the use of funds, it is supposed to improve both Fairfield was still using this decentralized approach to budget-

management and morale by giving more discretion to those ing in 1792, 13 years after its introduction. City officials

who actually administer the program. The more decentralized believed that the system was more efficient than traditional

approach gives line managers the flexibility to manage their line-item budgeting in that it made managers more responsible,

resources in more creative ways and to respond to changing reduced inter-departmental conflict at budget time, and encour-

conditions. In that way, it allegedly departs from the rigidity aged thrift and efficiency in operations.

446 Public Adrmnhtration Review + September/October 193, Vol. 53, No. 5

savings, on a descending scale. A department can keep 100

Recent stdiesofbudgeting in s a w 1 industrial percent of the first 25 percent of savings end a lesser percent-

age of any saving above that level. Westminster officials

believe that this provides an incentive for departments to save

h e c r a c k s indicate that a number of national and to avoid the year-end spending spree.5

gommenis are struggling toward a common method A similar modified approach is used by the San Diego cam-

pus of the University of California. In contrast with the highly

centralized budgetary process at most of the other UC cam-

that one author calls "budgetingfor resulis." puses, UCSD allocates by line-item but then gives greater dis-

cretion to program directors over the use of the funds. For

Dade County, Florida, has used a slmdar approach. Faced example, deans and department chairs are given "the flexibili-

with a loss of federal revenue-sharing funds in fiscal year 1986- ty to move funds more freely between line items than in the

87 and constrained by its property tax limit, the county faced .more centralized past." In addition, limitations on carrying

revenue growth of less than 1 percent for the next fiscal year. forward unexpended funds have been relaxed somewhat, sub-

That meant an across-the-board cut of about 20 percent for all ject to state-imposed restrictions. However, the university has

departments from the normal expected budget for the follow- no ability to transfer funds from the operating to the capital

ing year. At that point, the county instituted a budgetary budget, as the two are funded from different sources.6 This

approach that it called "profit sharing," in which each depart- points up a restriction that a state agency might face that a city

ment was allowed greater autonomy in managing its funds, government might not. For a state agency, the decision to use

and could retain most of a year-end balance. County officials the fuller version of decentralized budgeting would have to be

believe that the increased efficiency that resulted from the new made at the state capitol.

approach saved or generated $11 million. Like Fairfield, Dade

County also received a public administration award for its use

of the new method (Dade County News, February 8, 1988).

Budgeting for Results

Recent studies of budgeting in several industrial democra-

The city of Chandler, Arizona, has also used expenditure

cies indicate that a number of national governments are strug-

control budgeting in recent years. In Chandler, the base budget

gling toward a common method that one author calls "budget-

is adjusted annually for population growth and inflation to pro-

duce a current services budget. Department managers are ing for results." Allen Schick (1990) looked at national

budgeting in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Sweden, and

given maximum autonomy in managing their budgets, including

Britain, and from the richness of his descriptive detail, one can

carrying forward any unspent funds. Managers are expected to

pursue efficiencies that will generate savings that can be used extract several qualities that virtually all of the governmental

for future years' programs. Program managers generally are efforts have in common. In one form or another, each gov-

responsible for providing the funds to meet service levels that ernment is trying to achieve central control of total spending,

decentralization of authority to departments in the use of the

cannot be covered by the automatic annual adjustments for

funds, and enhanced accountability for results.

population and inflation. Unexpected demands on de~artmental

budgets can be handled by 'contingency fund traisfers that In response to the fiscal stress and cutbacks of the 1970s

require approval by the city manager and city council. and 1980s, the British government launched its "financial man-

Chandler city officials believe that the new way of budgeting agement initiatives" in 1982. Under this system, the cabinet

has motivated program managers to pay greater attention to pri- decides overall spending limits with Treasury advice, but then

orities and results. The city manager said that the new the Treasury loosens its control somewhat more than in the

approach saved the city over $2 million in fiscal year 1986-87.4 past, giving departments more discretion over how to use the

- -

The city of Westminster, Colorado, uses what it calls a modi- money. Within limits, each department is free to use the

fied decentralized approach to budgeting. The city council resources in the ways its managers believe will be most effi-

appropriates by line-item but then gives department managers cient and effective. For example, in 1988, the Treasury

considerable discretion to move funds from one line-item to replaced central manpower ceilings for departments with

another. In a theoretical sense, one could argue that line-item overall financial limits on administrative costs; now each

and decentralized budgeting are incompatible in that line-item department can decide on its mix of personnel and equip-

is a method of centralized control. But the relationship ment, as long as the total cost does not exceed the specified

between centralization and decentralization can be seen as a limit. However, that enhanced discretion is accompanied by

continuum, not a sharp dichotomy. The use of line-items, but increased accountability for results. In collaboration with the

with greater latitude than in the past, allows policy makers to Treasury, each department is expected to develop measures of

grant more discretion while simultaneously retaining a comfort- performance and, in fact, a recent government White Paper

able vestige of central control in case they want to reassert that listed over 1,800output and performance measures.

control later. (Knowing that you have a way to retreat can make In 1979, the Canadian federal government took a major

you more willing to advance.) Westminster has found that giv- step toward giving high-level policy makers greater control

ing department heads the ability to transfer between line items over total spending and priorities with the introduction of

provides greater flexibility for them to acquire capital equip what came to be known as "envelope budgeting." Programs

ment, to hire temporary employees, and generally to allocate were collected into broad policy sectors, or envelopes, such as

resources efficiently throughout the year. At year's end, the defense, social development, and economic development.

city council also allows departments to retain some of their The cabinet then decided on the allocation of funds to the

Entrepreneurial Budgeting: An Emerging Refonn? 447

envelopes in an effort to gain enhanced control over both

total spending and relative sectoral shares. Within their broad

allocations, officials were granted some discretion to move

A MajOrgoai of ¢ralization is to encourage the

funds around. Because funds for new initiatives generally had

to be found within a sector's or program's overall allocation,

deveoopment $a new administratiz culture in which

managers had an incentive to delete unproductive activities so

that funds could be made available for the new initiatives pogram managmseetheiro~ectiueas~'mum

(McCaffery, 1784). In envelope budgeting, however, the

emphasis was on sectoral allocation by the cabinet, rather achieuement with the available resources, ratherthan

than on decentralization of management and accountability for

results. Perhaps for that reason, in 1986 the Canadian govern-

ment introduced a more decentralized budgeting system called

asaquidng the largestpossiblebudgetfor their

"Increased Ministerial Authority and Accountability" (IMAA).

Although the cabinet decides on the overall budget and on the programs and then spending all they get.

allocation for various broad categories, such as defense and target levels. ~n one of the most dramatic innovations in bud-

health, departments have more "discretion over many adminis- geting in the world, it also has experimented with allowing the

trative matters previously requiring central approval" (Schick, employees themselves to retain some of the savings resulting

1770, p. 27). For example, departments now have broader from unusually high productivity gains. The Ministry of

authority over the reallocation of resources without Treasury Finance has also tried to spur productivity by lending money to

or cabinet approval. They can reallocate funds from one pro- agencies for the acquisition of new technology and by allow-

gram to another and can carry some unused funds into the ing agencies to carry forward some unspent funds if they are

next fiscal year. In exchange for the enhanced discretion, used for projects that will improve productivity.

however, IMAA requires greater accountability for results.

New Zealand has also adopted a budget system that

"Memoranda of Understanding" are negotiated between the

emphasizes achievement of objectives, rather than close moni-

Treasury Board and the departments. These are virtually con-

toring of line-item expenditures. This was part of a broad

tractual relationships by which the departments receive greater

move away from traditional government provision of services

stability of resources and greater discretion in the use of those

and toward a in which many functions

resources in exchange for an agreement to achieve certain lev- were either privatized or made relatively independent of gov-

of performance. The departmen' set forth 'pecific ernment control, numerous economic activities were ®u-

objectives in hierarchical order and indicate how they will be lated and the traditional civil service rules were loosened

measured and monitored. The Treasury Board recognizes that (Scot; al., 1770).

quantitative measures are not always feasible, and it also sug-

gests that departments should be selective in reporting those In all of these countries, a major goal of decentralization is

indicators that ministers would find the most useful in &crib- to encourage the development of a new administrative culture

ing the accomplishments of each program. Nonetheless, in which program managers See their objective as maximum

despite those brakes, there is an unmistakable move toward achievement with the available resources, rather than as

greater accountability for results. acquiring the largest possible budget for their programs and

then spending all they get. However, further research is need-

Australia has followed a similar pattern. After decades of ed to determine if have been into managers,

highly centralized financial control in government, a 1784

White Paper on budget reform recommended greater decen-

tralization of managerial decision making and enhanced Budgeting at the Pentagon

accountability by departments. This quotation from an Recent proposals for reforming defense budgeting bear

A~Straliangovernment study could ~h-iosthave come from a striking resemblances to the two approaches discussed above.

discussion of entrepreneurial budgeting in one of the U.S. In the five decades since it was created, the Defense

cities mentioned above: "More devolution of responsibility to Department has undergone two major changes in the way

agencies and, within them to line managers, ~ ~ c x - Ito

- I ~be the resources are allocated. In the Defense Reorganization Act of

greatest incentive that can be provided for improved manage- 1758, President Eisenhower and Congress uied to refom mili-

ment performance ....[Butl increased responsibility has to be tary structure by increasing the authority of the Office of the

matched with increased accountability" (Schick, 1770, p. 27). Secretary of Defense and reorganizing the combat commands

Tl~eAustralian government has done this in three ways--the along regional lines. In a passage that sounds like the justifi-

collapse of 21 line items into two, decentralization of resource cation for expenditure control budgeting in Fairfield,

management within each department, and development of an California, one author says:

evaluation capacity within each department.

Eisenhower wanted to decentralize operational author-

Like most of the other governments mentioned, Denmark ity and responsibility to mission and theater comrnan-

has been motivated partly by fiscal limitations. In recent years, ders, because he believed that the combatant com-

the government has cut the funds available to agencies, and so manders were potentially best situated and motivated

it is making a special effort to increase productivity as a way to to plan operations and to determine the size and com-

avoid cutting services too starkly. To encourage greater prc- position of forces required to accomplish their

ductivity, the Danish government allows agencies to keep any assigned combat missions, as well as to carry them out

savings that result from increases in productivity that exceed (Thompson, 1991, p. 55).

448 public Adrmnistration Review .

September/Oaober 1993,Vol. 53, NO. 5

However, the reform did not have the intended result of would have the authority to allocate funds to the combatant

increasing combat readiness, primarily because combatant commands, rather than to the uniformed senices. That would

commanders had to accept the military units the services be the centralized aspect of their scheme. From that point,

chose to supply, and the uniformed services retained full decision making would be more decentralized than it is now.

administrative control over those forces. Therefore, because The combatant commanders would use their funds to pur-

decentralization occurred in form only, the Eisenhower chase personnel and equipment from training and support

reforms merely made a very complex bureaucracy even more commands and to lease facilities and weapons systems from

complex. the private sector. Purchasing and leasing would be carried

out in a set of markets that would operate much as a private

A similar development occurred during the McNamara

economy does. Combatant commanders would bid for sup-

years. PPBS was instituted in the Defense Department by

plies and personnel; suppliers would sell their wares to the

Secretary Robert McNamara and Comptroller Charles Hitch in

highest bidder, and prices would be raised or lowered to

an effort to enhance the military's pursuit of national security

goals. Instead of organizing budgets only by inputs (e.g., per- bring demand into line with supply.

sonnel) and administrative units (e.g., the army), PPBS orga- Whether the Jones-Doyle and Gansler proposals are feasi-

nized the budget request by functions to be performed. The ble or not, their commonalities are striking. They involve cen-

system was centralized in that the goals were established by tralized priority setting, decentralized implementation, and

top-level policy makers, but it was decentralized in that lower- enhanced accountability for results. They involve some cen-

level officials were given considerable discretion in the meth- tralization in the sense of having top-level decision makers

ods that could be used to achieve the goals. McNamara said such as the President, Congress, and Joint Chiefs focus more

that he wanted to push all decisions to the lowest appropriate on policies and priorities and less on the details of micro-man-

level. In addition, the system sought to establish a clearer link agement. They involve considerable devolution of authority

between goals, performance, and rewards. Defense to line managers. Finally, they would require greater account-

comptrollers Charles Hitch and later Robert Anthony tried to ability from those line managers for the results achieved.

install "results-oriented operational budgeting." Anthony pro-

posed an accounting structure that "was firmly grounded in The timing of these proposals for defense decentralization

the principles of responsibility budgeting and accounting" may be partly a result of the fact that defense budgeting has

(Thompson 1991, p. 581.7 actually become more centralized in recent years. Defense

analyst J. Ronald Fox of the Harvard Business School believes

Although PPBS was probably more successful in the that Congress asserted greater control of the weapons acquisi-

Defense Department than in most federal agencies, many of tions process and other aspects of the defense budget after

the reforms of the McNamara period did not become fully 1970 for a series of reasons, including Vietnam, Watergate, the

operational even in Defense, partly because of the Vietnam growth of congressional staff, cost overruns, and spectacular

conflict. Various authors, however, argue that the essential incidents such as the $600 ashtray. Thus Congress saw micro-

elements of the Eisenhower-McNamara reforms should still be management "as a necessary and natural response to the

pursued. Jacques Gansler, for example, wants Congress to Defense Department's failure to manage its own affairs" (Fox,

concern itself with large policy questions such as foreign poli- 1988, p. 85).

cy goals, strategic choices, and the allocation of resources to

broad military missions. He would "restructure the budget

process so that Congress will be forced to vote on 'top-line'

dollars for the various 'mission areas' rather than on the details Common Qualities

of specific programs and projects that are clearly identified

with districts and states" (Gansler, 1989, p. 120). In his pro- Proposals for budgetary reform have emerged in the 1980s

posal, Congress would restrict itself to establishing broad poli- and 1990s for local budgeting in the United States, for defense

cy guidelines. It would delegate more authority to the budgeting, and for national budgeting in other industrial

Department of Defense to choose among weapons systems, democracies. These proposals have at least three qualities in

deploy rmlitary units, and so on. Gansler would even put an common.

end to congressional apportionment of military expenditure by

state and district as wasteful and irrational. Although it may Central Control of Goals

be politically naive to think that Congress would delegate its Entrepreneurial budgeting, mission budgeting, and budget-

authority to the degree that Gansler recommends, it is enlight-ing for results all involve some centralization, usually in two

ening to see how often decentralization of decision making in ways. First, central decision makers maintain control over the

defense budgeting is proposed. Finally, Gansler calls for more total amount of spending. Different governments may mean

real evaluation to "allow decision makers to assess the outputsdifferent things by "control of the total." A local government

realized and the accomplishments achieved against the dollars may impose a total spending ceiling of $100 million for fiscal

expended" (Gansler, 1989, p. 329). year 1993, while a national government may restrict the total

Another dramatic proposal to restructure defense spending budget increase next year to, say, 7 percent. For example, in

along the lines of mission budgeting has been offered by L. R. recent years the Swedish government has tried to limit govern-

Jones and R. B. Doyle (19891, professors of financial manage- ment spending to about 60 percent of gross national product.

ment at the Naval Postgraduate School. Under their scheme, Second, central policy makers usually decide total spending

the budget authority granted by President and Congress would for broad functions, such as health, public safety, or roads. A

be general, rather than detailed. The Joint Chiefs of Staff government may decide to allocate X percent for health, Y

Entrepreneurial Budgeting: An Emerging Reform? 449

I"

percent for income maintenance, and so on. The central con-

trol of totals and priorities is a salient characteristic of, and no latest trend!in budgeting contain

doubt one of the major motivations for, these reform propos-

als.

elernenk @the earlier r g o m .

Decentralization of Means

performance budgeting, functional categories from program

At the same time that budgeting remains or even becomes budgeting, negotiation of objectives from management by

more centralized in the above ways, it is also decentralized in objectives, and ranking of objectives from zero-base budget-

important ways. Once the overall total and the allocation to

ing. But there are some differences between the old reforms

broad functions have been decided by central policy makers, and the latest ones. The latter are generally simpler, more

program managers are then given considerably more discre- streamlined, and require less paperwork and analysis. They

tion over how they spend their money. Government man- involve more discretion by line managers than did the earlier

agers are treated more like business managers. They might be reforms, and there is a much greater emphasis on accountabil-

given more discretion to move money around among line ity than under the older formats. Finally, the recent reforms

items, such as from salaries to supplies, or to move money are motivated by a desire to change fundamentally the culture

from operations to capital spending. In addition, they might of public management by turning bureaucrats into

be allowed to carry over a significant portion of a year-end entrepreneurs. Previous budgetary reforms pursued legality,

surplus to the next fiscal year. The literature on efficiency, and effectiveness. The present wave of budgetary

entrepreneurial budgeting says that many local governments reform aims to stimulate motivbion. The new approaches

allow program managers to carry over about 30 .to 50 percent incorporate most of the goals of the previous reforms, but

of their year-end "surplus" to the new fiscal year in order to they seek to achieve them through decentralized incentives

avoid the "waste" of the surplus in a year-end spending spree. that give program managers greater authority to combine

Therefore, both the chief executive and the program managers resources as they think best but that hold the managers

supposedly benefit from the increased flexibility-the chief accountable for the results. These two qualities are virtually a

executive by contending with less waste and the program definition of entrepreneurship.

manager by enjoying greater discretion.

Accountability for Results Reasons For Decentralization

of course, higher-level decision makers ask something in TO the extent that these proposals and reforms constitute a

return for the increased discretion that they give to lower-level

trend, what accounts for itl It appears that two factors are

officials. Primarily, they want greater evidence of Program particularly important: fiscal stress and the perceived

achievement, particularly efficiency. Often an almost contrac- decentralization.

of

tual agreement is negotiated between the central budget office

and the operating departments in which each department lists It is a common observation that governments throughout

and ranks its objectives, specifies indicators for measuring the the world were faced with a more difficult fiscal problem in

achievement of those objectives, and quantifies the indicators the 1970s and 1980s than in the 1950s and 1960s. This fiscal

as far as ~ossible. problem was a result of the combination of increased demand

for public services and growing taxpayer resistance to higher

Paradoxically, these new approaches all call for additional taxes, a situation that has been called the "scissors crisis" in

centralization and decentralization at the same time. At first

public finance (Tarschys, 1983). People in the industrial

glance, these two qualities might appear to be incompatible,

democracies wanted more and more government services, but

but, in fact, organizations often centralize in order to decen-

they were not always willing to pay higher taxes to fund those

tralize (Perrow, 1977). Once those at the top are confident

services. Resistance to higher taxes began at the local level in

that their goals will be pursued by those below, they are more

the United States at least as early as the 1960s, as bond issues

willing to give those subordinates greater discretion to decide

and tax overrides began to fail with greater frequency. Then

on the methods to employ. To be effective, such devolution

the big bang came in 1978 with Proposition 13 in California,

of authority must be accompanied by a clear specification of

followed by similar measures in other states. The slowdown

goals, authority, and responsibilities. Decentralization requires

in economic growth after 1970 exacerbated the problem. This

prior clarification of the purpose of each administrative unit,

fiscal stress prompted adaptive behavior by governments,

procedures for setting objectives and for monitoring and

including more privatization, contracting out, increased user

rewarding performance, and a control structure that links each

fees, and an array of other devices either to make government

unit to the goals of the organization as a whole. That is, provision of services more efficient or to shift the burden for

incentives are specified in advance in order to entice members

to behave in ways consistent with the goals of the larger orga- the financing of those services. Virtually every account of the

decentralized approach to budgeting at the local level men-

nization. Thus devolution comes at a price, namely some

assurance that the units will efficiently pursue the goals of the tions fiscal stress as a major reason for its adoption (for exam-

larger organization. Hence centralization and decentralization ple, Osborne and Gaebler, 1992, pp. 2, 119-120). The fiscal

can go together.8 stress brought on by the combination of slower economic

growth, taxpayer resistance, and ever-increasing demand for

Clearly, the latest trends in budgeting contain elements of public services is also given as a major reason for the move to

the earlier reforms. They contain performance measures from budgeting for results by industrialized countries (Schick, 1990,

450 Public Adminkbation Review r September/October 1993,Vol. 53,No. 5

are based explicitly on that literature. Citing William

The computem'zationofaccounting has made it Niskanen, Robert Anthony, Frederick Mosher, and other schol-

ars of organization, Thompson (1991) emphasizes the irnpor-

tance of a clear definition of purpose, devolution of decision

possible for central bLu&et offies to exercise greater making about means, and close accountability through

responsibility budgeting and accounting. Indeed, he argues

cmhd control w the Aetails of$mdirg thanpreuhsly. that: "It has been demonstrated to the satisfaction of most stu-

dents of management that the effectiveness of large, complex

pp. 26, 29, 30). The cutbacks that are impending in the 1990s organizations improves when authority is delegated down into

are also given by Thompson and other analysts as a reason for the organization along with responsibility" (p. 53). Although

reviving and refining the proposals for decentralization of the explicitness of the relationship between organization liter-

defense budgeting (Thompson, 1991, p. 64). If the decentral- ature and the decision to propose decentralized budgeting

ized approach has not attracted more support within the fed- varies by individual, most of the participants seem to be aware

eral government to this point, perhaps it is partly because, of the connection.

unlike localities, the federal government can run a deficit and This is not to say that the trend described above has been

hence does not face the same fiscal discipline as do local gov- universal. Robert D. Lee's (1991) study of developments in

ernments. state budgeting over the past 20 years suggests that two of the

One adaptation to fiscal stress was for policy makers to three qualities discussed above have become more prominent

take greater control of total spending in order to retard incre- at the state level, but not necessarily the third. He found that

mental budget growth at the same time that they gave pro- state policy makers and central budget officers had increased

gram managers greater discretion in the detailed use of the their control of goals and limits. Compared to 1970, they are

funds. In fact, to the extent that they get a firmer grip on total now more apt to specify priorities and dollar ceilings and to

amounts, policy makers are often willing to grant greater dis- provide other forms of policy guidance in telling agencies

cretion. They hope that the decentralization and more inten- how to prepare their budget requests. This is consistent with

sive accountability will lead to greater efficiency and effective- our point about the centralization of goals. Likewise, they are

ness with the funds available. It is not an accident that these now far more likely to require agencies to provide measures

techniques emerged soon after the beginning of the taxpayer of productivity and effectiveness either in their budget

revolt in the late 1970s. requests or in subsequent documents. The proportion of state

governments that required such data rose dramatically from

A second source of the budget reforms is the accumulating about 25 percent in 1970 to about 90 percent in 1990. This is

body of knowledge on the virtues of decentralized organiza- consistent with our point about the movement toward greater

tion. The literature on organizations suggests a model of accountability of agencies for achieving results with the funds

behavior something like this: If policy makers want an organi- that they receive.

zation to pursue the policy-makers' goals efficiently, they

should clearly specify the goals, and perhaps even involve However, the computerization of accounting has made it

subordinates in the setting of those goals. They should then possible for central budget offices to exercise greater central

create a structure of incentives that will motivate subordinates control over the details of spending than previously. Lee

to pursue those goals but give them a high degree of autono- found that the proportion of states in which the central budget

my in the choice of methods. In a mutually reinforcing way, office exercised control over the transfer of funds from one

this will allow workers to exercise their creativity, which will major object of expenditure to another (such as from supplies

give them more satisfaction, thereby making them more pro- to personnel) rose slightly from 59 percent in 1970 to 72 per-

ductive, and allow them to generate better solutions to the cent in 1990, and the number of budget offices that exercised

problems that they face because they are closer to the prob- control over transfer of funds from one minor object to anoth-

lem and probably have better information about it. At the er (e.g., from office supplies to painting) rose from 10 to 20

same time, the delegation of authority will leave those at the percent. While these figures run against any alleged trend

top more time to think about goals and to monitor perfor- toward decentralization of the means of administration, they

mance. are perhaps not very large increases in actual control in light

of the greater capacity for control provided by the computeri-

The recent reforms of budgeting appear to be firmly zation of accounting. It can, therefore, be said that-with the

grounded in the research on decentralization. The local man- exception mentioned here-state governments have also

agers emphasize incentives, participation, creativity, and other moved in the same direction as the local and national govern-

qualities that the research mentions as alleged virtues of ments.

decentralized management. Likewise, the budget leaders in

the other industrial democracies base the recent reforms on

organization theory. Although Schick does not explicitly

address the question of the intellectual foundations of the lat- Conclusion

est reforms, it is clear that the reforms are an outgrowth of This article has examined an approach to budgeting that

research on organization theory, and specifically on an analy- uses decentralized incentives as a way to stimulate

sis of the virtues of decentralization. Because the proposals entrepreneurial behavior by public administrators. After top

for mission budgeting at the Pentagon are made by scholars policy makers have established their overall control through

who are familiar with the literature on organization theory and broad guidelines, the new methods decentralize decision mak-

institutional economics, it is not surprising that their arguments ing by providing agency managers with incentives to be both

Entrepreneurial Budgeting: An Emerging Reform? 451

efficient and effective. In addition, the new methods aim to

make administrators more accountable for the results of their

decisions by monitoring actual performance more than in the

IThe k r e e to zuh, the e ~ r refom

b w e

I

past. The goal is to motivate -managers to behave more in

harmony with the purposes of the overall organization and to

rgected may haue been o-ted. A r m t study

lessen the "suboptimization" that often characterizes public

programs. Ultimately, a goal is to change the culture of public IhdiCatedthata m a j o v o f m u n i C z ( p a l g o ~ ~ ~

I

management.

If it is true, as Wildavsky (1978) has argued, that the tradi- continue to use most ofthe toots created in recentyears

tional budget has lasted because it is workable and because it

fulfills various functions for policy makers, it is also true that .forincreain~e f f ~ k y ~

the traditional budget has persistently come under attack.10

esced in the cuts because they were given greater discretion in

The fact that reforms are so regularly tried (about one each

the use of the remaining funds). The alleged savings may be

decade since the 1950s) suggests that something was wrong

real, but further research is needed to test the claims. A relat-

with traditional budgeting. Although budgetary reforms are

ed problem is that the available descriptions of the reforms

often oversold and do not perform up to their advance billing,

generally do not provide data in forms that allow a clear cal-

they almost always leave their mark. In fact, the degree to

culation of the magnitude of the savings even if we could

which the earlier reforms were rejected may have been over-

agree on the meaning of the term. For example, in addition

stated. A recent study indicated that a majority of municipal

to being told that a city's departments spent $6 million less

governments continue to use most of the tools created in

than they were appropriated, we need to know how many

recent years for increasing efficiency. For example, 75 percent

use performance monitoring, 70 percent still use program bud- years are covered by this figure, what the total budgeted

amounts were (so percentage savings can be calculated), and

geting at least to some degree, and over 30 percent even use

so on. Moreover, the fact that entrepreneurial budgeting at

elements of zero-base budgeting (Poister and Streib, 1989).

the local level has been used mainly by relatively small gov-

Moreover, the decentralized approach is in harmony with the

ernments raises the question of its applicability to larger cities

near consensus in management theory today-that a certain

and states. However, the fact that several national govern-

kind of decentralized organization can be efficient, account-

ments are using a simiiar approach takes some of the thrust

able, and satisfying to workers. For these reasons, it seems

out of this criticism. Logically, entrepreneurial budgeting

likely that this emerging trend will have a lasting effect on

should be even more appropriate for large and complex orga-

budgeting, even if it does not transform the budgetary process

as much as its advocates hope. nizations than for small and simple ones precisely because, in

decentralizing the middle step (implementation), it makes the

However, a number of cautions should be noted. first and,third steps (goal setting and monitoring) more man-

Proposed reforms have almost always followed a pattern ageable for policy makers. Moreover, if this approach to bud-

characterized by initial enthusiasm and subsequent disap- geting is well grounded in organization theory, it should stand

pointment, for at least two reasons. First, the reforms are a good chance of being relatively successful. However,

often difficult to put into practice. Entrepreneurial budgeting enthusiasts should keep in mind the checkered history of

is similar in various ways to performance budgeting, pro- those earlier reforms.

gram budgeting, management by objectives, and zero-base

budgeting. For example, it requires measures of perfor- In addition there is the question of whether decentraliza-

mance and outcomes that are not always easy to construct tion is actually dangerous. Theodore Lowi (1979) is con-

for government programs. However, entrepreneurial budget- cerned about the proclivity of policy makers in the United

ing is simpler than the earlier reforms, and, in fact, that is States to delegate too much vague authority to administrators

one of its attractions for policy makers. In addition, consid- and to interest groups without clear indication of what they

erable progress has been made in the construction of perfor- are authorized to do. With regard to the enormous delegation

mance measures, and it is possible that evaluation of pro- of authority granted by federal statutes since the 1930s, Lowi

grams can be done better today than in earlier decades. In warned that "Delegation of power ...turned out to be ...a gift of

any case, Lee's (1991) study of state budget developments sovereignty to private satrapies" (also M c C O M ~1967).

~ ~ , It is

shows that far more governments are conducting efficiency conceivable that entrepreneurial budgeting might beguile poli-

and effectiveness studies today than 20 years ago (also see cy makers into abdicating responsibility to bureaucrats for the

Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; and Hatry et al., 1990). making of public policy. Even if they grant more discretion to

administrators, policy makers must still decide on relative pri-

A second reason for eventual disappointment is that orities, specify &ha; they want accomplished with the fuAds,

reforms sometimes fail to make any substantive difference in and develop measures of the results. In short, policy makers

resource allocation or program performance. In this regard, must be careful that in delegating more authority to adminis-

many of the claims by local governments of greater efficiency trators to decide how to pursue goals, they do not inadvertent-

and effectiveness from decentralized budgeting so far are ly delegate decisions about what goals to pursue. However,

vague and difficult to assess. Managers claim "savings" of vari- as Lowi points out, it is possible to delegate authority in ways

ous amounts, but it is seldom clear what they mean. They are that do not relinquish authority. A strong and clear rule has

truly savings only if efficiency is enhanced or if the new both centralizing and decentralizing effects; it centralizes

method allowed cuts that otherwise were not feasible to make authority in the hands of policy makers but decentralizes the

(for example, managers and their interest group clients acqui- implementation within clear guidelines for the use of the

452 Public Admh&ation Review September/October 1993,Vol. 53, NO. 5

authority. Like Lowi's "juridical democracy," the proposals This managerial revolution seems to be part of a larger

described here could give policy makers more control of over- institutional transformation sweeping the world, a revolution

all policy direction while delegating more of the details of of decentralization that includes the movement for choice in

implementation to administrators. By relieving policy makers education, devolution of power to Indian tribes," contracting

of the burden of detailed scrutiny of the process by which out by local governments, privatization in Latin America, and

program goals are achieved, decentralized budgeting could even the decommunization of Eastern Europe. A major

allow them more time to devote to the .goals themselves. implication of these changes is that institutions characterized

Thus entrepreneurial budgeting, and decentralized manage- by overly centralized decision making and lack of account-

ment in general, can lead to an expansion of power, rather ability for socially useful results do not work very well.

than to a redistribution of power. If entrepreneurial budgeting

These budgetary proposals can thus be seen as manifesta-

works as claimed, policy makers should have more of the

power that is relevant to their task and subordinates should tions of a larger institutional revolution that has occurred in

recent years. It is obvious that the "market" as a device for

also have more power to do their jobs. In short, it could

allocating resources has experienced a resurgence. After

enhance governmental capacity, rather than redistribute gov-

ernmental authority. Of course, unless superiors specify what decades of movement toward centralized decision making as

activities are acceptable, subordinates may become too "cre- a way to allocate resources, governments in the United States

ative" in their entrepreneurship. A few years ago, for exam- and other countries are now contracting out services or pri-

ple, California policy makers believed that the state's comrnu- vatizing public enterprises as never before. Whether one is

nity colleges demonstrated excessive creativity in thinking of as enthusiastic about this trend as its most zealous advocates

new ways to attract additional state funds (Cothran, 1981 and (for example, Savas, 1987), the indisputable fact is that the

1986). use of market-like incentives has enjoyed a notable revival in

recent years. Indeed, the return of largely centralized

As was m e of the earlier budget reforms, this latest one is economies back to more decentralized arrangements is one

not likely to be the salvation of modern government as it of the great political-economic transformations of the late

struggles to provide the benefits that people expect while 20th century. Although Eastern Europe and the former Soviet

staying within the fiscal restraints that voters have imposed. Union have received the most attention, other areas of the

However, this reform may have even more effect than the oth- world such as Latin America are also caught up in the enthu-

ers because it actually involves less, not more, work by most siasm for the market and for decentralization in general.

participants and it is in keeping with the findings of research Mexico, for example, reduced the number of its state-owned

on organizational behavior in recent decades. If it fails, it enterprises from about 1,200 in 1982 to about 300 by 1992.

probably will not do much damage, but if it succeeds, it could A similar trend toward decentralized incentives can be seen

contribute to the creation of a new entrepreneurial manage- in business in the United States, where the idea of managers

ment culture in public administration. and workers personally gaining some of the benefits of their

The budget reforms are part of a larger managerial revolu- increased productivity is currently very much in favor. In

tion that includes such techniques as management by objec- fact, some business analysts are predicting that "gainsharing"

tives, management information systems, performance monitor- as a way to improve productivity will become one of the

ing, program evaluation, total quality management, and others. fastest growing business strategies in the country in the

A consensus seems to be emerging among scholars of organi- 1990s (Graham-Moore and Ross 1990). The trend toward

zation about what constitutes good management. For exam- decentralized decision making and incentives is, therefore,

ple, in their analysis of 70 studies of the use of management by spread across a number of countries and institutions. In

objectives, Rodgers and Hunter (1992) found that MBO-type budgeting as in political economy in general, this might be

processes have become more widely used in both government 'called the "age of incentives."

and business and that they have almost always had a positive

effect on productivity when supported by top management.

What we have called entrepreneurial budgeting bears a striking Dan A. Cothran is professor of political science at

resemblance to MBO. The latter usually comprises three p r e Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Arizona. His

cessesparticipatory decision making, goal setting, and objec- research interests include public budgeting and finance,

tive feedback (Rodgers and Hunter, 1992), which are very sirni- comparative public policies, and political democratization.

lar to the three components of entrepreneurial budgeting. In He has published articles in such journals as Public

turn, both MBO and entrepreneurial budgeting are similar to Budgeting and Finance, Policy Studies Review, and Western

"total quality management," especially as modified for use in Political Quarterly. He is currently working on research on

government (Swiss, 1992). Arizona public finance and on democratization in Mexico.

Notes

The author thanks Fred Thompson, Glenn Phelps, Jane Juarez, and several 2. In addition to a survey of recent literature on budgeting, for this section I

anonymous referees for very helpful suggestions on this article. communicated with 20 local governments that were mentioned in the lit-

1. While the arrangement by decade makes a neater presentation and is erature as having instituted decentralized budgeting.

approximately correct, the actual dates are not so orderly. For example, 3. David Creighton, city of Fairfield, letter to author, November 8, 19%.

performance budgeting was proposed long before the 1950s, Proposition 4. Pat Walker, city of Chandler, telephone interview with author, April 22,

13 was enacted in 1978, and the attempt to enact a balanced budget 1991.

amendment continued at least until its defeat in Congress in 1992. 5. Alan Milla; aty of Wesfminter, Colorado, lecter to author, November 26,1330.

Entrepreneurial Budgeting: An Emerging Refom?

6. Robert Brents, University of California at San Diego, letter to author, 9. Austin and Larkey, 1992; Vining and Weimer, 1990; Marcus, 1988;

November 20,1990. Denhardt, 1984; Williamson, 1975; Rumelt, 1974; Turcotte, 1974;

7. Here Thompson draws upon Anthony (1962) and Anthony and Young Golembiewski, 1972; Chandler, 1966; Crozier, 1964; Argyris, 1962;

(1988). McGregor, 1960; Simon, 1957.

8. Incentives stated in advance should not be confused with controls put in 10. In hi recent writings, Widavsky (1988) seems to have relented a bit in his

place in advance, or ex ante. For a more elaborate discussion of ex ante defense of traditional budgeting. See also Rubin (1989).

controls and when they are appropriate, see Thompson and Jones 0986). 11. A proposal made by Senator Dennis DeConani in 1990 (Arizona Republic,

April 28, 1990).

References

Anthony, Robert, 1962. "New Frontiers in Defense Financial Management." McConnell, Grant, 1967. Private Power and American Democracy. New York:

n e Federal Accountant, vol. 11 (June), pp. 13-32. Alfred A. Knopf.

Anthony, Robert and David Young, 1988. Management Contml in Nonprofit McGregor, Douglas, 1960. The Human Side ofEnterprise. New York: McGraw-

Organizations, 4th ed. Homewood, IL: Irwin. Hill.

Argyris, Chris, 1962. Interpersonal Competence and Organizational Osborne, David and Ted Gaebler, 1992. Reinventing Government. Reading,

Effectivenes~.Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press. MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.

Arizona Republic, 1990, April 28. Perow, Charles, 1977. "The Bureaucratic Paradox: The Efficient Organization

Austin, Robert and Patrick Larkey, 1992. "The Unintended Consequences of Centralizes in Order to Decentralize." Organization Dyltamics (Spring),

Micromanagement: The Case of Procuring Mission Critical Computer pp. 3-14.

Resources." Policy Sciences, vol. 25, no. 1 (February), pp. 3-28. Poister, Theodore and Gregory Streib, 1989. "Management Tools in Municipal

Bellone, Carl, 1988. "Public Entrepreneurship: New Role Expectations for Government: Trends Over the Past Decade." Public Administration

Local Governrnent." UrbanAnalys@,vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 71-86. Review, vol. 49 (May/June), pp. 240-248.

Cal-TmNews,June 1, 1987, p. 10. Rodgers, Robert and John E. Hunter, 1992. "A Foundation of Good

Chandler, Alfred D., 1966. Strategy and Structure. Garden City, NY: Management Practices in Government: Management by Objectives." Public

Doubleday and Co. AdminGtration Review, vol. 52 (lanuary/February), pp. 27-39.

Cothran, Dan A,, 1981. "Program Flexibility and Budget Growth." Western Rubin, Irene, 1989. "Aaron Wildavsky and the Demise of Incrementalism."

Political Quattdy, vol. 34 (December), pp. 593-610. Public Administration Review, vol. 49 Uanuary/February), pp. 78-81.

, 1986. "Some Sources of Budgetary Uncontrollability: The Rumelt, Richard, 1974. Strategy, Structure, and Economic Performance.

Interaction of Automatic Funding and Program Flexibility." Public Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Budgeting and Finance, vol. 6 (Summer), pp. 45-62. Savas, E.S., 1987. Privatizatton: The Key to Better Government. Chatham, NJ:

, 1987. "Japanese Bureaucrats and Policy Implementation: Lessons Chatham House Publishers.

for America?"Policy Studies Review, vol. 6, (February), pp. 439458. Schick, Allen, 1990. "Budgeting for Results: Recent Developments in Five

Crozier, Michel, 1964. Ihe Bureaucratic Phenomenon. Chicago: University of Industrialized Countries." Public Administration Review, vol. 50

Chicago Press. (january/February), pp. 26-34.

Dude County News, 1988, February 8. Scon, Graham, Peter Bushnell, and Nikiti Sallee, 1990. "Reform of the Core

Denhardt, Robert, 1984. Theories of Public Organization. Monterey, CA: Public Sector: New Zealand Experience." Governance: An International

Brooks/Cole Publishing Co. Journal ofpolicy and Administration, vol. 3 (April), pp. 138-167.

Fox, J. Ronald, 1988. The Defense Management Challenge: Weapons Simon, Herbert, 1957. M d k ofMan. New York: John Wiey and Sons.

Acquisition. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press. Swiss, James E., 1992. "Adapting Total Quality Management to Governrnent."

Gaebler Group, 1988. Expenditure Control Budgeting System. San Rafael, CA: Public Administration Review, vol. 52 Uuly/August), pp. 356362.

Gaebler Group. Tarschys, Daniel, 1983. "The Sassors Crisis in Public Finance." Policy Sciences,

Gansler, Jacques, 1989. Affording Defense. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press. vol. 15, no. 3 (April), pp. 205-224.

Golembiewski, Robert, 1972. Renewing Organizations. Itasca, IL: Peacock. Thompson, Fred, 1991. "Management Control and the Pentagon: The

Graham-Moore, Brian and Timothy L. Ross, 1990. Gainshan'ng: Plans for Organizational Strategy-Structure Mismatch." Public Administration

Improving Petfomance. Washington, DC: Bureau of National Affairs, Inc. Review, vol. 51 uanuary/February), pp. 5246.

Hatry, Harry, et al, 1390. Service Effoorts and Accomplishments Reporting: Its Thompson, Fred and L.R. Jones, 1986. "Controllership in the Public Sector."

Time Has Come. Norwalk, CT.: Governmental Accounting Standards Journal of Policy analysis and Management, vol. 51 (January/February),

Board. pp. 52-66.

Jones, L.R. and R.B. Doyle, 1989. "Public Policy Issues in Budgeting for Turcone, William E., 1974. "Control Systems, Performance, and Satisfaction in

Defense." Paper Delivered at the 11th annual Research Conference of the Two State Agencies." Administrative Science Quar?dy, vol. 19 (March),

Association for Public Policy and Management." Arlington, VA (November pp. 60-73.

3). Vining, Aidan and David Weimer, 1990. "Government Supply and

Lee, Robert D., 1991. "Developments in State Budgeting: Trends of Two Government Production Failure: A Framework Based on Contestability."

Decades." Public Administration Review, vol. 51 (May/June), pp. 254-262. Journal of Public Policy, vol. 10, pp. 1-22.

Lowi, Theodore J., 1979. The End of Liberalism: The Second Republic of the Wildavsky, Aaron, 1978. "A Budget for All Seasons: Why the Traditional

United States, 2d ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Co. Budget last^.^ Public Administration Review, vol. 38 (November/

Marcus, Alfred, 1988. "Responses to Externally Induced Innovation: Their December), pp. 501-509.

Effects on Organizational Performance." Strategic Management Journal, , 1988. The New Politics of the Budgetary Process. Glenview, IL:

vol. 9 (July-August),pp. 387402. Scon-Foresmad Little Brown.

McCaffery, Jerry, 1984. "Canada's Envelope Budgeting: A Strategic Williamson, Oliver, 1975. Markets and Hierarchies New York: The Free Press.

Management System." Public Administrative Reufew,vol. 44 (july/August),

pp. 316-323.

Public Adminismtion Review + September/october 193, VO~.53, No. 5

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Network Sovereignty: Building The Internet Across Indian CountryDokument19 SeitenNetwork Sovereignty: Building The Internet Across Indian CountryUniversity of Washington PressNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Four Dimensions of Public Financial ManagementDokument9 SeitenThe Four Dimensions of Public Financial ManagementInternational Consortium on Governmental Financial Management100% (2)

- Seawater Intrusion in The Ground Water Aquifer in The Kota Bharu District KelantanDokument8 SeitenSeawater Intrusion in The Ground Water Aquifer in The Kota Bharu District KelantanGlobal Research and Development ServicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor Law IDokument132 SeitenLabor Law ICeledonio ManubagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theory of The BudgetDokument30 SeitenTheory of The Budgetivymarie reblora83% (12)

- Language Policies - Impact On Language Maintenance and TeachingDokument11 SeitenLanguage Policies - Impact On Language Maintenance and TeachingMiss-Angel Fifi MarissaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marxist Literary TheoryDokument3 SeitenMarxist Literary TheoryChoco Mallow100% (2)

- Chavez V PEA and AMARIDokument12 SeitenChavez V PEA and AMARISteve Rojano ArcillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ireland and The Impacts of BrexitDokument62 SeitenIreland and The Impacts of BrexitSeabanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Local Government Zero Based BudgetingDokument4 SeitenLocal Government Zero Based BudgetingVanessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mais Qutami - The Veil (De) Contextualized and Nations "Democratized": Unsettling War, Visibilities, and U.S. HegemonyDokument22 SeitenMais Qutami - The Veil (De) Contextualized and Nations "Democratized": Unsettling War, Visibilities, and U.S. HegemonyM. L. LandersNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Performance-Based Budgeting: A Review of Experience and Lessons", Indian Journal of Social Work, 72 (4), October 2011, Pp. 483-504.Dokument21 Seiten"Performance-Based Budgeting: A Review of Experience and Lessons", Indian Journal of Social Work, 72 (4), October 2011, Pp. 483-504.ramakumarrNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-Introduction To Islamic EconomicsDokument45 Seiten1-Introduction To Islamic EconomicsDaniyal100% (4)

- [IMF Working Papers] Does Performance Budgeting Work? An Analytical Review of the Empirical LiteratureDokument49 Seiten[IMF Working Papers] Does Performance Budgeting Work? An Analytical Review of the Empirical LiteratureHAMIDOU ATIRBI CÉPHASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proposition V: The Extent To Which Decisions Are Based Upon KnowlDokument8 SeitenProposition V: The Extent To Which Decisions Are Based Upon KnowlAlann BartoluzzioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wiley American Society For Public AdministrationDokument14 SeitenWiley American Society For Public AdministrationAlann BartoluzzioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessing Goals and Objectives of Outcome Budgeting Across Government LevelsDokument22 SeitenAssessing Goals and Objectives of Outcome Budgeting Across Government LevelsMwabilu NgoyiNoch keine Bewertungen

- PPM 2019 02 Ibrahim PDFDokument11 SeitenPPM 2019 02 Ibrahim PDFasfand yar aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zero Base Budgeting in Historical and Political Context Institutionalizing An Old ProposalDokument19 SeitenZero Base Budgeting in Historical and Political Context Institutionalizing An Old ProposalGarlic LahsunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond Budgeting - ArticlesDokument32 SeitenBeyond Budgeting - Articlesagarai100% (1)

- Compass Financial - Fidelity - Stimulus ScorecardDokument4 SeitenCompass Financial - Fidelity - Stimulus Scorecardcompassfinancial100% (2)

- ManagementofpublicfundsDokument9 SeitenManagementofpublicfundsNabeelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting and Rebudgeting in Local GovernmentsDokument15 SeitenBudgeting and Rebudgeting in Local GovernmentsDhinoTuasamuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget Process Reform Ideas AnalyzedDokument24 SeitenBudget Process Reform Ideas AnalyzedJake Dan-AzumiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ZBB Report on Zero-Based BudgetingDokument29 SeitenZBB Report on Zero-Based BudgetingPriya DesaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Aggregation On BudgetingDokument18 SeitenEffects of Aggregation On BudgetingYayi WulanninggarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rules and Flexibility in Public Budgeting: The Case of Budget Modernisation in AustraliaDokument13 SeitenRules and Flexibility in Public Budgeting: The Case of Budget Modernisation in AustraliaGitaSeptianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting Systems and Their Applicability in Public Sector: January 2001Dokument21 SeitenBudgeting Systems and Their Applicability in Public Sector: January 2001JoséNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chand (1977)Dokument45 SeitenChand (1977)Fredy A. CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Sector EconomicsDokument3 SeitenPublic Sector Economicsmuyi kunleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Friedman 1Dokument21 SeitenFriedman 1eska.nibberingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authority, Acceptance, Ability and Performance-Based Budgeting ReformsDokument13 SeitenAuthority, Acceptance, Ability and Performance-Based Budgeting ReformsAcwin CethinkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelly Et Al - 2008 - Budget Theory in Local Government - The Process-Outcome ConundrumDokument25 SeitenKelly Et Al - 2008 - Budget Theory in Local Government - The Process-Outcome ConundrumjosephineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyDokument15 SeitenMeasurement of Poverty and Poverty of Measurement: Martin GreeleyKule89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Institutional IssuesDokument29 SeitenInstitutional IssuesJojit Domingo Dela Cruz - SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fiscal Policy in Developing CountriesDokument3 SeitenFiscal Policy in Developing CountriesKyaw Htet AungNoch keine Bewertungen

- PIERSON-rotado (1) - Compressed-ComprimidoDokument31 SeitenPIERSON-rotado (1) - Compressed-ComprimidoDeysi Alexandra Varillas SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gibson Planning For Economy in Developing CountriesDokument12 SeitenGibson Planning For Economy in Developing CountriesOwais AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- WPS5316 (1) - Part-6Dokument11 SeitenWPS5316 (1) - Part-6Enzo van der SluijsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Un Pan 000526Dokument42 SeitenUn Pan 000526Praptaning Budi UtamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budget Administration in Emerging Democracies: Budgets and The Democratic ProcessDokument23 SeitenBudget Administration in Emerging Democracies: Budgets and The Democratic ProcessprabodhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgetary SlackDokument19 SeitenBudgetary SlackwinarsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three familiar options for mobilizing funds analyzedDokument3 SeitenThree familiar options for mobilizing funds analyzedRon VitorNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOMEWORKDokument4 SeitenHOMEWORKcyralizmalaluanNoch keine Bewertungen

- CMA Project Group5Dokument21 SeitenCMA Project Group5SIMRAN SHOKEENNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding The Politics of The Budget: January 2007Dokument24 SeitenUnderstanding The Politics of The Budget: January 2007Sohilauw 1899Noch keine Bewertungen

- Epa 005Dokument7 SeitenEpa 005AakashMalhotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Financial Management 4Dokument10 SeitenPublic Financial Management 4Muguti EriazeriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting As A Mechanism For Management Planning and ControlDokument50 SeitenBudgeting As A Mechanism For Management Planning and ControlMatthewOdaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting and Budgetary Control As The Metric For Corporate PerformanceDokument33 SeitenBudgeting and Budgetary Control As The Metric For Corporate PerformanceLê Ly NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting PHDokument4 SeitenBudgeting PHJewel Patricia MoaNoch keine Bewertungen

- WWW Cambridge Org - Pbidi.unam - MX Nudging Is Being FramedDokument5 SeitenWWW Cambridge Org - Pbidi.unam - MX Nudging Is Being Framedrezaferidooni00Noch keine Bewertungen

- NAO Good Budgeting ResearchDokument71 SeitenNAO Good Budgeting Researchramya14Noch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Budgeting in The U.S. Federal Government: History, Status and Future ImplicationsDokument43 SeitenPerformance Budgeting in The U.S. Federal Government: History, Status and Future ImplicationsSilent ReaderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lucas 2003Dokument14 SeitenLucas 2003LucianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance-Based Budgeting Implementation Process: The Nashville-Metropolitan Government ExperienceDokument16 SeitenPerformance-Based Budgeting Implementation Process: The Nashville-Metropolitan Government ExperiencekarthikanachimuthuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflicting Views of PBB Success in State BudgetingDokument16 SeitenConflicting Views of PBB Success in State BudgetingHaley EricksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zero Based Budgeting - Group5Dokument24 SeitenZero Based Budgeting - Group5SIMRAN SHOKEENNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIH Public Access: Measuring The Level and Inequality of Wealth: An Application To ChinaDokument26 SeitenNIH Public Access: Measuring The Level and Inequality of Wealth: An Application To Chinaulfathea mulyaditaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financ Acc Manag - 2021 - Krishnan - Decision Making Processes of Public Sector Accounting Reforms in India InstitutionalDokument28 SeitenFinanc Acc Manag - 2021 - Krishnan - Decision Making Processes of Public Sector Accounting Reforms in India InstitutionalShiv KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decampos 2016Dokument10 SeitenDecampos 2016Quỳnh Anh NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conference On Macro and Growth Policies in The Wake of The Crisis Washington, D.CDokument13 SeitenConference On Macro and Growth Policies in The Wake of The Crisis Washington, D.CVarun SolankiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public-Sector Performance: Steven J. BallaDokument4 SeitenPublic-Sector Performance: Steven J. BallaPaulRahakbauwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joyce 1993 (PUAD 505)Dokument16 SeitenJoyce 1993 (PUAD 505)Haley EricksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Development Drives Economic GrowthDokument18 SeitenFinancial Development Drives Economic GrowthMuhammad HairullaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distiguishing May June1995 PDFDokument15 SeitenDistiguishing May June1995 PDFrubel86Noch keine Bewertungen

- "Designing Zero-Based Budgeting For Public Organizations": AuthorsDokument12 Seiten"Designing Zero-Based Budgeting For Public Organizations": AuthorsRaúl Guerrero RodasNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Logit Model For Budget Allocation Subject To Multi Budget SourcesDokument17 SeitenA Logit Model For Budget Allocation Subject To Multi Budget SourcesKHAIRUR RIJALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation On Moshe DayanDokument23 SeitenPresentation On Moshe DayanVibuthiya Vitharana100% (4)

- Air and Space LawDokument10 SeitenAir and Space Lawinderpreet sumanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annual Barangay Youth Investment Program 2019Dokument3 SeitenAnnual Barangay Youth Investment Program 2019Kurt Texon JovenNoch keine Bewertungen

- SUPREME COURT RULES ON MINORITY EDUCATION RIGHTSDokument108 SeitenSUPREME COURT RULES ON MINORITY EDUCATION RIGHTSDolashree K MysoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prosecution Witness List For DiMasi TrialDokument4 SeitenProsecution Witness List For DiMasi TrialWBURNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outcomes Of Democracy Class 10 Notes PDF - Download Class 10 Chapter 7 Revision NotesDokument7 SeitenOutcomes Of Democracy Class 10 Notes PDF - Download Class 10 Chapter 7 Revision Notestejpalsingh120% (1)

- Global Divides The North and The South - Bryan OcierDokument17 SeitenGlobal Divides The North and The South - Bryan OcierBRYAN D. OCIER, BSE - ENGLISH,Noch keine Bewertungen

- Means and Ends !!: Madhuri MalhotraDokument34 SeitenMeans and Ends !!: Madhuri MalhotraAkansha bhardwajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master ListDokument305 SeitenMaster Listjuan100% (2)

- Full Text of "John Birch Society": See Other FormatsDokument301 SeitenFull Text of "John Birch Society": See Other FormatsIfix AnythingNoch keine Bewertungen