Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

INRIX Covid Safe Streets Utilization Analysis-1-1

Hochgeladen von

DCOH EditorCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

INRIX Covid Safe Streets Utilization Analysis-1-1

Hochgeladen von

DCOH EditorCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Utilization of COVID-19 Street

Programs in 5 U.S. Cities

Bob Pishue, Transportation Analyst, INRIX

ABOUT INRIX RESEARCH

Launched in 2016, INRIX Research uses INRIX proprietary big data

and expertise to make the movement of people and goods more

efficient, safer and convenient.

We achieve this by leveraging billions of anonymous data points

every day from a diverse set of sources on all roads in countries of

coverage. Our data provides a rich and fertile picture of urban mobility

that enables INRIX Research to produce valuable and actionable

insights for policy makers, transport professionals, automakers,

and drivers.

The INRIX Research team has researchers in Europe and North

America, and is comprised of economists, transportation policy

specialists and data scientists with backgrounds from academia,

think tanks and commercial research and development groups.

We have decades of experience in applying rigorous, cutting-edge

methodologies to answer salient, real-world problems.

INRIX Research will continue to develop the INRIX Traffic Scorecard

as a global, annual benchmark as well as develop new industry-

leading metrics and original research reports. In addition to our

research outputs, INRIX Research is a free and valuable resource for

journalists, researchers and policymakers. We are able to assist with

data, analysis and expert commentary on all aspects of urban mobility

and smart cities. Spokespeople are available globally for interviews.

2 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

KEY FINDINGS:

• Total activity on restricted streets lagged overall city activity significantly in

New York, and somewhat significantly in Washington D.C., while activity

in Oakland was slightly higher on restricted streets and significantly higher in

Minneapolis.

• New York City’s Full Block implementation saw higher levels of activity (78%)

than “Open Restaurant” streets (62%) and far higher levels of activity

compared to “Protected Bike Lane” streets (51%). Designs geared toward

the commuting in Manhattan, seemed to attract fewer people and cyclists

than those geared toward recreation.

• Minneapolis’s recreational-focused streets saw the largest increase in activity

out of the five cities studied, however their program was shelved

by September.

• Seattle’s and Minneapolis’ shared streets saw more unique visitors versus

control streets possibly due to the recreational nature of the programs.

• Activity near Oakland’s “Slow Streets” was significantly higher on those with

more visits from lower-income households. Low activity was observed on

streets with a greater share of high-income visitors.

• Pass-through trips appear to have been significantly reduced.

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 3

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

METHODOLOGY

INRIX analyzed “safe street” programs in Minneapolis, New York, Oakland, Seattle and Washington DC

based on their respective size, implementation, length of operation and the relative permanence of

changes made for these projects

Two types of analyses were done to study these restricted street programs:

1) Normalized INRIX Visits data by census block. This analysis looks at activity at census

blocks that intersect with a restricted street. These streets are then compared to the cities’ proper

to determine how utilization compares to the city as a whole. We consider this an activity metric.

2) INRIX Visits “Home Location” data: This analysis is used to determine the visit characteristics

(frequency, demographics, etc.) on a particular corridor or set of corridors. Control streets were

chosen based on utilization, location, functional classification and direction.

IMAGE 1 Screenshot of INRIX Visits analysis of New York City

BACKGROUND

Since health officials imposed COVID-19 restrictions on public and private gatherings, road authorities

across the world have implemented several policies to promote social distancing, cycling and walking, all

while decreasing car use on a particular street. These programs have been given different monikers –

“Slow Street,” “Safe Street,” “Stay Healthy Street,” “Keep Moving Street” or another variant – depending

on the city. While all “restricted streets” attempt to limit car traffic, our research reveals that different

versions of these programs can be implemented based on the goals of transportation officials and

public use.

Closing a public street is not a silver bullet for urban policy goals, and there are a number of justifications

as to why a street should be closed: safety, cut-through traffic, social distancing, economic stimulus (open

dining, open-air retail, etc.), recreation (increase walking and cycling for adults and children), commuting

(shifting commute mode from auto to bike/ped), reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improving access

for essential trips (grocery stores, pharmacies, hospitals, other services), among others.

4 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

During COVID-19, a reduction in traffic has allowed public officials to implement these policies with

minimal opposition. Yet as Figure 1 shows, traffic is returning, and as congestion builds on highways and

freeways, drivers will seek less-congested arterial and city streets for travel. With continued growth in

vehicle-miles traveled, city officials face mounting pressure to reopen streets, requiring strong quantitative

analysis to determine if (and how) these changes should be made permanent.

FIGURE 1 Demand for car travel continues to increase

However, there is often a gap between clearly articulated project goals and metrics leveraged to

measure relative success. For example, should a street see less activity, for social distancing and lack

of through traffic, or more activity, with increased person-throughput?

To provide insight into project performance, INRIX analyzed streets in five different cities to reveal how

these “restricted” streets operated and performed. While this information helps public officials make

a more informed decision regarding specific projects, it also provides road authorities the ability to

share key information with the public.

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 5

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

FINDINGS

Monthly Utilization

Utilization versus other streets is a simple method of analyzing restricted streets. However, it is critical

that officials implementing restricted streets clearly define its specific context and goal. For example,

public agencies may want less overall vehicle traffic while simultaneously desiring more pedestrian

and bicycle traffic. Since bicycle traffic is often a fraction of vehicle traffic, however, even a doubling

or tripling of cycling along a corridor may have a negligible effect on traffic patterns. Therefore, it is

important that public agencies define a specific street’s purpose to accurately gauge the program’s

success or failure.

FIGURE 2 Normalized and Month-to-Month Change in Trip Share

Figure 2 provides the utilization of restricted streets and their respective control streets across the five

cities analyzed. After seeing an increase in trip-share versus control streets during March and April,

streets that were a part of Seattle’s “Keep Moving Streets” saw utilization begin to fall even before project

implementation this summer. This may be as intended, as Keep Moving Streets are “located on streets

with higher speed and traffic volume than Stay Healthy Streets and are temporarily closed to cut-through

traffic.” The numbers are also likely affected by multiple park closures since COVID-19 to limit gathering

sizes in public spaces.

Minneapolis saw traffic build prior to implementation of its restricted streets, which began on April 29,

A slight dip in May led to a six percent rebound in June. Officials ended the pilot program in September

despite seeing a 32% higher utilization versus control streets in August.

Other programs, like those found in New York, Oakland and Washington DC, ranged from a one percent

reduction in trip share to a 16% reduction versus control streets.

6 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

Visitor Characteristics

One measure of performance may be the frequency of new visitors using the restricted streets. In some

instances, restricted streets attract new people from outside the neighborhood, like a public park.

As referenced in Figure 3, both Minneapolis’s and Seattle’s restricted streets had a larger share of unique

visitors than the control streets, indicating those facilities may be more recreationally focused rather than

“destination-based.” This is interesting given that the utilization/trip share of restricted streets in Minneapolis

and Seattle are inversely related.

FIGURE 3 By eliminating and restricting parking and thru-

traffic, cities may be discouraging those from outer

Unique Visitor Share by City neighborhoods frequenting restaurant districts and other

street-based activities. Figure 3 shows, for example, that

unique visitor counts on restricted streets in Oakland,

New York City and Washington D.C. tracked their open,

control street counterparts.

Often, these programs are carefully analyzed to ensure

equitable access for all residents. This analysis can

include key demographics like race, household income,

family size and access to a vehicle. For this example,

we examined all restricted streets in Oakland in terms of

activity along with household income.

Our analysis found that activity along Oakland’s Slow

Streets significantly varied by income. For example, Image

2 reveals that 58th & Dover, 42nd/48th/Webster, and

16th & West all had a very high share of visits from the

high-income group ($90,000+) along with lower than

average activity (below 53%). While Brookdale/Humboldt

IMAGE 2 Oakland Street Activity & and Arthur/Plymouth had relatively larger shares of low-

Visitor Share by Income Group income visitors (21% and 23%, respectively) and higher

activity. However, nearly a third of Oakland households

report an income of less than $45,000 per year (Census

Bureau B19001), and all Slow Streets analyzed in

Oakland fell below that portion for the lower income group

using the project.

This suggests that while activity is greatest along those

streets with a larger lower-income share of visitors,

lower-income households were underrepresented.

This representation varied significantly depending on

street location.

Visitors to 58th & Dover had the highest income per

unique visitor of all streets analyzed at $92,500, while

East 16th had the lowest income per unique visitor at

Low = MI less than $45,000/year; Middle = MI

$45,000-$90,000; High = MI $90,000+ $60,500.

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 7

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

Comparing Street Activity to Overall City Activity

Though comparing restricted streets to control streets can be informative, another metric to understand

is activity along the corridor. This metric indicates an uptick of general activity in the “neighborhood” or

“district” versus simply the street right of way. Figure 4 provides insight into activity and compares it to the

activity within the city proper.

FIGURE 4 Activity by City

Looking at the entire City of Seattle provides useful insights. In the “Monthly utilization” metric, we saw

Seattle’s “Keep Moving Streets” plummet in usage versus nearby control streets. Yet when looking at all “Stay

Healthy Streets” compared to the overall activity within the city, Stay Healthy Streets outpaced the rest of

the city significantly. This finding reveals the importance of specific quantitative performance metrics tailored

toward street design. In other words, a one-size fits all metric may not perform well across all street types.

Table 1 compares activity levels on restricted streets to activity across the respective city. Minneapolis saw

the largest jumps on their restricted streets, with activity levels in July one-third higher than pre-COVID.

While Washington DC had the lowest utilization of any city, activity city-wide was on-par with restricted lane

use. Restricted bike lanes in New York, on the other hand, saw the lowest activity in relation to the city as

a whole, likely due to the drop in commuter activity in Manhattan as a result of COVID, where the bulk of

restricted streets are located (see Figure 5).

8 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

TABLE 1 Activity by City, by Month, Comparison

% ACTIVITY ON RESTRICTED

CITY PERIOD % ACTIVITY CITYWIDE

STREETS

Minneapolis APRIL 54% 41%

Minneapolis MAY 83% 76%

Minneapolis JUNE 105% 85%

Minneapolis JULY 133% 85%

Minneapolis AUG/SEPT 75% 82%

New York City APRIL 24% 31%

New York City MAY 53% 68%

New York City JUNE 64% 77%

New York City JULY 68% 87%

New York City AUG/SEPT 66% 86%

Oakland APRIL 46% 38%

Oakland MAY 56% 54%

Oakland JUNE 59% 57%

Oakland JULY 67% 66%

Oakland AUG/SEPT 59% 52%

Seattle APRIL 46% 35%

Seattle MAY 70% 59%

Seattle JUNE 78% 65%

Seattle JULY 82% 75%

Seattle AUG/SEPT 82% 72%

Washington, DC APRIL 32% 30%

Washington, DC MAY 44% 48%

Washington, DC JUNE 50% 59%

Washington, DC JULY 53% 54%

Washington, DC AUG/SEPT 52% 52%

New York City Activity, Explained

New York City’s usage of restricted streets appears to lag other cities, needing further investigation to

determine the cause. First, New York adopted fairly strict social distancing and travel restrictions, which

may have affected activity considerably by borough, as shown in yellow in Figure 5. The low activity seen

on restricted streets in New York (blue) is weighted heavily on the general lack of activity in Manhattan,

which comprises the large majority of restricted streets analyzed (in terms of Census Blocks that intersect

with a restricted street, not length of streets).

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 9

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

FIGURE 5 New York City Activity by Borough

Delving further, we decipher which type of streets saw the largest activity. As shown in Figure 6, “Full

Block” restrictions (general neighborhood street closures) saw the largest gains in activity versus pre-

COVID level, surpassing 80% in July. Yet restaurants, and especially protected bike lanes (PBL) lagged

behind. Again, this has to do with the outsized impact Manhattan has on the results, as PBL’s and

Restaurant-related street restrictions are heavily concentrated in Manhattan, while Brooklyn, Queens and

Manhattan share higher amounts of Full Block streets. Due to the varying nature of street closures

surrounding restaurants, a time of day and day of week analysis is warranted

FIGURE 6 Activity by Street Type, New York

10 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

Passthrough Traffic Study, Alki Beach, Seattle, WA

Nearly all restricted street programs attempt to restrict the number of vehicles on a roadway. Many of

these streets are only open to vehicles that: 1) have a destination on that street (local access); 2) are

non-motorized; or 3) local delivery vehicles. As a result, it is important to understand the impact to

adjacent streets and determine how detours are functioning.

Alki in Seattle, WA, a peninsula, provides an interesting test case. In this example, Beach Drive and Alki

Ave SW were closed to motorized vehicles on May 7, 2020 between 63rd Ave SW on the North and South.

INRIX Trips data indicate that vehicle trips dropped 20% on Beach Drive/Alki Ave in between March and

May, yet trips jumped 44% on 63rd Ave SW.

FIGURE 7 Passthrough trips by street (% of total trips)

City-wide traffic and related congestion is still below pre-COVID level. However, likely due to displaced vehicles

from closing Beach Drive/Alki Ave, traffic volumes on 63rd Ave SW mirror last year. This indicates that traffic

congestion, while similar to last year with diversion onto the street, would likely be lower had Alki not been

closed to through traffic.

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 11

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

Conclusion

Using INRIX Visits, along with INRIX Trips, and U.S. Census demographics, allows a deeper look into

non-traditional roadways. In all but New York, average daily traffic data has been limited or non-existent

regarding many of the closed and controlled streets, likely due to costs of collection and monitoring,

in addition to analytical time. Using INRIX Visits allows we were able to approximate relative volumes,

agnostic of mode, in order to compare street activity before and after changes. In this study, we found:

motorists are largely obeying through-traffic restrictions; utilization of restricted streets varies with the

type of program offered; unique visitors are more prevalent in some street closings versus others; and the

importance of location on user demographics.

This data is especially valuable given the demands for finite roadway space once traffic and congestion

return to pre-COVID levels. There was also little factoring of seasonality, as Spring and Summer may

represent a larger user base than Fall and Winter. With continued monitoring public officials can determine

the best way to maximize person throughput and public right of way utilization throughout the city.

Appendix

Additional information not used in the report, but beneficial to analysis.

Time of Day & Day of Week

Time of day patterns allow public officials to make more informed decisions when it comes to closing

streets. For example, many restricted streets have hour requirements, like 8AM to 8PM, or go 24 hours, 7

days per week. Figure 4 provides the trip distribution, by hour, for restricted streets by city, starting in April.

Trip Distribution Metrics – By Hour

Out of all of the cities analyzed, Seattle stands out as having the most unequal distribution . Seattle has the

largest share of any city between 1PM and 5PM and the smallest share of trips between 8PM and 8AM, at just

12%. Visits in Minneapolis are spread fairly evenly throughout the day, while New York City, DC,and Oakland share

similar distributions somewhere between these extremes. It is important to note that street selection in Seattle

may be skewing the results, as these “Keep Moving Streets” were placed near heavy recreation.

12 INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD

UTILIZATION OF COVID-19 STREET PROGRAMS IN 5 U.S. CITIES

NORTH AMERICA EMEA

10210 NE Points Drive Station House

Suite 400 Stamford New Road

Kirkland Altrincham

WA 98033 Cheshire

United States WA14 1EP

England

+1 425-284-3800

info@inrix.com +44 161 927 3600

europe@inrix.com

INRIX RESEARCH | INTELLIGENCE THAT MOVES THE WORLD 13

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- 1.12. Building Projection Over Public StreetDokument6 Seiten1.12. Building Projection Over Public StreetGian SanchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- South College Avenue Medians Villa Maria To CarsonDokument65 SeitenSouth College Avenue Medians Villa Maria To CarsonKBTXNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Living Streets - Degree ProjectDokument106 SeitenLiving Streets - Degree ProjectSeth Geiser100% (1)

- Serv NYC ProjectDokument9 SeitenServ NYC ProjectAnshu BaidyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mayor Bowser Letter May 6 2021Dokument2 SeitenMayor Bowser Letter May 6 2021Washingtonian MagazineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post Schar PollDokument7 SeitenPost Schar PollDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ltr. To Dist Ct. Re Expiration of CDC Eviction Order Final 6-16-21Dokument3 SeitenLtr. To Dist Ct. Re Expiration of CDC Eviction Order Final 6-16-21DCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Covid Travel Monitoring Jan Feb 2021 Rev AllDokument6 SeitenCovid Travel Monitoring Jan Feb 2021 Rev AllDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20-1157 Sean Feucht Ministry Mall Permit - RedactedDokument36 Seiten20-1157 Sean Feucht Ministry Mall Permit - RedactedDaniel MillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Restraining Order - Anne Arundel CountyDokument4 SeitenRestraining Order - Anne Arundel CountyChris BerinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Item Q PresentationDokument49 SeitenItem Q PresentationDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- CM Mcduffie Reopen Letter May 2 2021Dokument2 SeitenCM Mcduffie Reopen Letter May 2 2021DCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- COVID Test AuditDokument133 SeitenCOVID Test AuditChris BerinatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12.16.2020 MDH Response DC COVID Reallocation RequestDokument1 Seite12.16.2020 MDH Response DC COVID Reallocation RequestDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Montgomery County Restaurant LawsuitDokument36 SeitenMontgomery County Restaurant LawsuitDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdvaGenix Letter To MoCo 8 18Dokument2 SeitenAdvaGenix Letter To MoCo 8 18DCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Archdiocese of Washington V BowserDokument31 SeitenArchdiocese of Washington V BowserWashingtonian MagazineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solidcore Phase Two Restrictions Letter To The MayorDokument2 SeitenSolidcore Phase Two Restrictions Letter To The MayorDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Union Letter To NorthamDokument1 SeiteUnion Letter To NorthamDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Capitol Hill Baptist Church Bowser LawsuitDokument26 SeitenCapitol Hill Baptist Church Bowser LawsuitDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antietam Battlefield KOA V HoganDokument32 SeitenAntietam Battlefield KOA V HoganHoward Friedman0% (1)

- Mayor Bowser Letter To Senate and House Leadership 7-20-20Dokument2 SeitenMayor Bowser Letter To Senate and House Leadership 7-20-20DCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20-0885 - Attachment - Outdoor Dining Program SummaryDokument2 Seiten20-0885 - Attachment - Outdoor Dining Program SummaryDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Expanding Testing CapacityDokument3 SeitenExpanding Testing CapacityDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2020 Employer Telework Survey PresentationDokument23 Seiten2020 Employer Telework Survey PresentationDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joint Region 7 Phase 1 LetterDokument2 SeitenJoint Region 7 Phase 1 LetterWJLA-TVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coronavirus Omnibus Emergency DECDokument4 SeitenCoronavirus Omnibus Emergency DECDCOH EditorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Covid Emergency: Jobs & Tax Crisis in The District of ColumbiaDokument23 SeitenCovid Emergency: Jobs & Tax Crisis in The District of ColumbiaMartin AustermuhleNoch keine Bewertungen

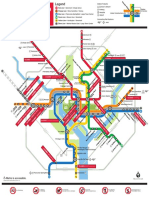

- 2019 System Map COVID-19 Stations FINALDokument1 Seite2019 System Map COVID-19 Stations FINALwtopwebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cashless Retailers Prohibition Act of 2018Dokument2 SeitenCashless Retailers Prohibition Act of 2018Team_GrossoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marikina City's Effective Urban Design CriteriaDokument3 SeitenMarikina City's Effective Urban Design CriteriaDanica Lyne Dela CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- CDI 4 Traffic MNGTDokument19 SeitenCDI 4 Traffic MNGTRoui FacunNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS BROCHUREDokument12 SeitenECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS BROCHUREXolani RadebeNoch keine Bewertungen

- UDPFI GuidelinesDokument48 SeitenUDPFI GuidelinesVineeta HariharanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neighborhood Environment Walkability ScaleDokument7 SeitenNeighborhood Environment Walkability Scalee_marroquinNoch keine Bewertungen

- HaDokument12 SeitenHahailabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Richard Solly - Bright Wings A Light-Hearted Tale of Disappointment, Destruction, Desperation and DeathDokument21 SeitenRichard Solly - Bright Wings A Light-Hearted Tale of Disappointment, Destruction, Desperation and DeathAustin Macauley Publishers Ltd.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Camden Central Community UmbrellaDokument98 SeitenCamden Central Community UmbrellaTom YoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- NJIT Landscape Master Plan - Goals and StrategiesDokument42 SeitenNJIT Landscape Master Plan - Goals and Strategiessbiswas21Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cttmo FunctionsDokument90 SeitenCttmo FunctionsChristian Paul PinoteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revitalizing Neglected Urban Spaces Using Place-Making PrinciplesDokument10 SeitenRevitalizing Neglected Urban Spaces Using Place-Making PrinciplesSandra SamirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Back of Port Part 2Dokument216 SeitenBack of Port Part 2Durban Chamber of Commerce and IndustryNoch keine Bewertungen

- ltn-2-08 Cycle Infrastructure Design PDFDokument92 Seitenltn-2-08 Cycle Infrastructure Design PDFHaribabu MakkenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TP021 Complete Streets PolicyDokument178 SeitenTP021 Complete Streets PolicynaimshaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes - 12 December 2019Dokument37 SeitenDesign Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes - 12 December 2019Franky KenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tab 1 Kaufman Lynn Construction Response To Phase II RFQ No. 2020-180-ND CompressedDokument50 SeitenTab 1 Kaufman Lynn Construction Response To Phase II RFQ No. 2020-180-ND Compressedthe next miamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMPACTS OF TRAFFIC ON COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES IN URBAN AREAS:by Yaweh Samuel KevinDokument20 SeitenIMPACTS OF TRAFFIC ON COMMERCIAL ACTIVITIES IN URBAN AREAS:by Yaweh Samuel Kevinskyna4Noch keine Bewertungen

- City of Kingston CMP Checklist 3 PDFDokument10 SeitenCity of Kingston CMP Checklist 3 PDFTariq JamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- City of Peterborough Draft Official PlanDokument220 SeitenCity of Peterborough Draft Official PlanPeterborough ExaminerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viva Vancouver - Manual Parklets PDFDokument76 SeitenViva Vancouver - Manual Parklets PDFAndreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clean Rivers Project: Northeast Boundary TunnelDokument32 SeitenClean Rivers Project: Northeast Boundary TunnelScott RobertsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Geylang Urban Design GuidelinesDokument6 SeitenGeylang Urban Design GuidelinesJackson TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- W. 120th Avenue Corridor Sub-Area PlanDokument41 SeitenW. 120th Avenue Corridor Sub-Area PlanAzharudin ZoechnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Street DesignDokument60 SeitenStreet DesignAh FeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philcoa, Diliman, Quezon City: Healthy CitiesDokument35 SeitenPhilcoa, Diliman, Quezon City: Healthy CitiesPat BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Municipal Art Society Report: A Bold Vision For The Future in East MidtownDokument65 SeitenMunicipal Art Society Report: A Bold Vision For The Future in East MidtownThe Municipal Art Society of New York100% (1)