Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

85 & 86: Le Costume Et Ses Accessoires À L'exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900, À Paris (Saint-Cloud: Belin Frères, 1900), P. 58

Hochgeladen von

nitakuri0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

6 Ansichten3 SeitenOriginaltitel

8.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

6 Ansichten3 Seiten85 & 86: Le Costume Et Ses Accessoires À L'exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900, À Paris (Saint-Cloud: Belin Frères, 1900), P. 58

Hochgeladen von

nitakuriCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

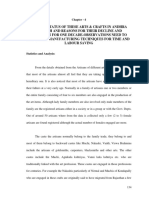

A photograph of Leloir, published in the catalog for the

1900 “Costumes anciens” exhibition at the Exposition Universelle, shows him

wearing a (yellow) brocaded silk robe de chambre from the July Monarchy

(1830–1848) (Musée rétrospectif des classes 85 & 86 1900, 58)

(Figure 1). The photograph reveals two stages of retouching: Leloir first

modified the garment (the front appears to have been cut up and reworked,

and the dressing gown may have been cut in two), donned it to have his

picture taken, and then drew over the printed photograph with white pencil to

rework his hair, goatee, shoes, and the jabot. As a source for the history of

collecting, this photograph is highly revealing. First, on a basic level it shows

that historic garments were being collected, photographed, and displayed. As

simple as this statement may seem, it is remarkable when put into context:

historical garments began to be included as sources within the disciplines of

history and archaeology in the 1850s and were first exhibited in 1874. Until

then, old garments, however precious their materials, were most often reused,

handed down, re-worked as fancy dress, or sold into the second-hand trade or

rag market (Charpy 2009, 2010). Leloir’s photograph shows a growing

awareness of the value of historic clothing.

Figure 1 Photograph of Maurice Leloir, “Robe de chamber soie jaune 1840.”

Archives Leloir / Départment des arts graphiques / Palais Galliera. Courtesy of

the Palais Galliera. Photograph reproduced in Musée rétrospectif des classes

85 & 86: le costume et ses accessoires à l'Exposition universelle

internationale de 1900, à Paris (Saint-Cloud: Belin Frères, 1900), p. 58.

Second, printed in an

exhibition catalog alongside other such images, Leloir’s photograph reveals

that the “visual turn” of dress history encompassed exhibition display and

print. The catalog for the first exhibition of dress history in 1874 contained only

textual descriptions of each room and the names of the lenders (Quatrième

exposition Musée historique du costume 1874). The catalog that accompanied

the second exhibition in 1892 featured longer descriptions of the rooms,

lenders, and several black-and-white drawings of the tableaux displays

(Exposition Des Arts de La Femme 1892). In 1900, the catalog for the

“Costumes anciens” exhibition not only included this photograph of Leloir, but

also presented nearly a hundred photographs of objects on display as well as

lengthy thematic essays about dress history (Musée rétrospectif des classes

85 & 86 1900). The catalogue’s layout was visually evocative and innovative:

text was printed diagonally next to photographs, photographs were doctored

to remove the model or mannequin from the garment, leaving the garment

disembodied, and thin onionskin paper printed with text was placed over a

photograph to create a playful overlay. The Leloir photograph also revealed a

third layer in the historiography of early French fashion collecting that was

further from our current practices, namely that of re-touching, re-working, and

re-constructing historic garments for display. This practice of “re-constructing”

garments was not evident in the first exhibition of historic dress in 1874, but

had gained traction in 1892 and 1900, and was in full use by the time Leloir

and the SHC organized its first exhibition of dress history in 1909. In 1900,

cutting up, re-piecing, and replacing components of historic garments was a

way for exhibition designers to make garments fit within the imaginative visual

displays that were becoming increasingly popular for the display of historic

dress.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Universelle, and Particularly in The Contribution of Maurice Leloir (1853-1940)Dokument2 SeitenUniverselle, and Particularly in The Contribution of Maurice Leloir (1853-1940)nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Collector-Amateur To Working-Collector: Defining The First Fashion Collectors at The 1874 "Musée Historique Du Costume"Dokument3 SeitenFrom Collector-Amateur To Working-Collector: Defining The First Fashion Collectors at The 1874 "Musée Historique Du Costume"nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationDokument2 SeitenFashion Collections, Collectors, and Exhibitions in France, 1874-1900: Historical Imagination, The Spectacular Past, and The Practice of RestorationnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 Fashion, History, Museums Inventing The Display of Dress by Julia PetrovDokument257 Seiten2019 Fashion, History, Museums Inventing The Display of Dress by Julia PetrovPaul Sebastian mesa100% (2)

- Victorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"Von EverandVictorian and Edwardian Fashions from "La Mode Illustrée"Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- Auctions and The Growth of The Union Centrale's Historic Garment CollectionDokument3 SeitenAuctions and The Growth of The Union Centrale's Historic Garment CollectionnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"Von EverandAuthentic French Fashions of the Twenties: 413 Costume Designs from "L'Art Et La Mode"Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (4)

- Art Nouveau Fashion Gultum, Casdam o Aut C. SeributuaDokument25 SeitenArt Nouveau Fashion Gultum, Casdam o Aut C. Seributuasumqueen67% (6)

- The Musée International d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-FondsVon EverandThe Musée International d’Horlogerie in La Chaux-de-FondsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paris SalonDokument2 SeitenParis SalonBojana100% (1)

- Garments As History: The Discipline of Dress History in Mid-Nineteenth-Century FranceDokument2 SeitenGarments As History: The Discipline of Dress History in Mid-Nineteenth-Century FrancenitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation 13Dokument8 SeitenPresentation 13ლიზი ფალელაშვილიNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Short History of Costume & Armour: Two Volumes Bound as OneVon EverandA Short History of Costume & Armour: Two Volumes Bound as OneBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (2)

- Art Nouveau Essay Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History The Metropolitan Museum of ArtDokument5 SeitenArt Nouveau Essay Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History The Metropolitan Museum of ArtAmanda MonteiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- REVIEW of EXHIBITION Grand Design - Pieter Coecke Van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry 2015Dokument8 SeitenREVIEW of EXHIBITION Grand Design - Pieter Coecke Van Aelst and Renaissance Tapestry 2015amadeomiller6964Noch keine Bewertungen

- Art DecoDokument22 SeitenArt DecoMau MalletNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taste and Fashion - From the French Revolution to the Present DayVon EverandTaste and Fashion - From the French Revolution to the Present DayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of The Idea of ExpositionsDokument20 SeitenRise of The Idea of Expositionsrajat charayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- British Costume from Earliest Times to 1820Von EverandBritish Costume from Earliest Times to 1820Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (8)

- Brittany and The Atlantic Rim in The Later First Millennium BC PDFDokument20 SeitenBrittany and The Atlantic Rim in The Later First Millennium BC PDFWagaJabalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color: 64 Engravings from the "Galerie des Modes," 1778-1787Von EverandEighteenth-Century French Fashion Plates in Full Color: 64 Engravings from the "Galerie des Modes," 1778-1787Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5)

- Masterpieces of Eighteenth-Century French Ironwork: With Over 300 IllustrationsVon EverandMasterpieces of Eighteenth-Century French Ironwork: With Over 300 IllustrationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brooklyn Museum Deaccessions at Christie'sDokument24 SeitenBrooklyn Museum Deaccessions at Christie'sLee Rosenbaum, CultureGrrlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and RevolutionVon EverandArt and the French Commune: Imagining Paris after War and RevolutionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exposition Internationale Des Arts Décoratifs Et Industriels Modernes BrusselsDokument2 SeitenExposition Internationale Des Arts Décoratifs Et Industriels Modernes BrusselsJEFFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cataloguing Musical IconographyDokument7 SeitenCataloguing Musical Iconographyi.got.cowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 2 - Movements Is Architecture-ART DECODokument27 SeitenLesson 2 - Movements Is Architecture-ART DECOGina Ann MaderaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Louvre Press Release Louvre LensDokument20 SeitenLouvre Press Release Louvre LensLorena Delgado PiñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalogue of European Court Swords and Hunting Swords PDFDokument303 SeitenCatalogue of European Court Swords and Hunting Swords PDFAmitabh Julyan100% (2)

- Ancient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian CostumeVon EverandAncient Egyptian, Mesopotamian & Persian CostumeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (8)

- Art DecoDokument20 SeitenArt DecoAhmed Saber50% (2)

- LouvreDokument11 SeitenLouvreGrasanul SecoluluiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exhibitions in Paris and Salon Des Refusés: By: Christian Jack SantanderDokument6 SeitenExhibitions in Paris and Salon Des Refusés: By: Christian Jack SantanderKRIS ANNE SAMUDIONoch keine Bewertungen

- 376 Decorative Allover Patterns from Historic Tilework and TextilesVon Everand376 Decorative Allover Patterns from Historic Tilework and TextilesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (4)

- AHIST 1401written Assignment Unit 5Dokument6 SeitenAHIST 1401written Assignment Unit 5Julius OwuondaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtDokument9 SeitenExhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtDiego Fernando GuerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Great ExhibitionDokument30 SeitenGreat ExhibitionNikhil GoyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Art DecoDokument3 SeitenWhat Is Art DecoNurLatifah Chairil AnwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- V. Steele, Museum Quality, Fashion Theory, 12.1Dokument25 SeitenV. Steele, Museum Quality, Fashion Theory, 12.1Ilaria PisanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 19th Century European Paintings and SculptureDokument52 Seiten19th Century European Paintings and Sculpturebackback100% (1)

- Lesson 2 - Movements Is Architecture-ART NOUVEAUDokument12 SeitenLesson 2 - Movements Is Architecture-ART NOUVEAUGina Ann MaderaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Greek, Roman & Byzantine CostumeVon EverandAncient Greek, Roman & Byzantine CostumeBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (12)

- Art Nouveau (/ Ɑ RT Nu Voʊ, Ɑ RDokument97 SeitenArt Nouveau (/ Ɑ RT Nu Voʊ, Ɑ RemmanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- French Tapestries and Textiles in The J. Paul Getty MuseumDokument207 SeitenFrench Tapestries and Textiles in The J. Paul Getty MuseumFloripondio19100% (4)

- The Archives and The Library: Palais Garnier Emperor Napoleon III Eugène Scribe Daniel AuberDokument2 SeitenThe Archives and The Library: Palais Garnier Emperor Napoleon III Eugène Scribe Daniel AubershobhrajNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion - A Fashion History of The 20th CenturyDokument680 SeitenFashion - A Fashion History of The 20th Centurydanabooks3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Modernism versus Traditionalism: Art in Paris, 1888-1889Von EverandModernism versus Traditionalism: Art in Paris, 1888-1889Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ancient Egyptian Furniture: Volume II - Boxes, Chests and FootstoolsVon EverandAncient Egyptian Furniture: Volume II - Boxes, Chests and FootstoolsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 1912 and 1915 Gustav Stickley Craftsman Furniture CatalogsVon EverandThe 1912 and 1915 Gustav Stickley Craftsman Furniture CatalogsBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (4)

- Boulle eDokument17 SeitenBoulle eLucio100Noch keine Bewertungen

- HumanDokument3 SeitenHumannitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Fashion StatementDokument2 SeitenGlobal Fashion StatementnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionDokument4 SeitenSalvatore Ferragamo Promotes Sustainability With Art and FashionnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- SweatshopDokument3 SeitenSweatshopnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- In The Late 1980s and Early 1990sDokument25 SeitenIn The Late 1980s and Early 1990snitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailDokument7 SeitenThe Technologies Reinventing Physical RetailnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)Dokument182 SeitenHandbook of Catholic Social Teaching (PDFDrive)nitakuri100% (2)

- Mother MaryDokument9 SeitenMother MarynitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eco Chic The Fashion ParadoxDokument5 SeitenEco Chic The Fashion ParadoxnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- LONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchDokument3 SeitenLONDON FASHION WEEK 2022 Ones To WatchnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conclusion: Chapter - 5Dokument41 SeitenConclusion: Chapter - 5nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eastern Region: Bengal and OrissaDokument14 SeitenEastern Region: Bengal and OrissanitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dior Brings Vacation PopDokument5 SeitenDior Brings Vacation PopnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Louis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022Dokument3 SeitenLouis Vuitton Investigates Counterfeit Selling Allegations in China June 9, 2022nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Lost Art of Himroo WeavingDokument7 SeitenThe Lost Art of Himroo WeavingnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeekDokument7 SeitenAngelo Flaccavento: Said Jonathan Anderson at The Beginning of The WeeknitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Widescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakeDokument6 SeitenWidescreen Escapism at Haute Couture: Tim'S TakenitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasDokument16 SeitenDiscuss in Detail The Costumes of The SatavahanasnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter - 1Dokument11 SeitenChapter - 1nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1Dokument3 SeitenAcknowledgements Plates: Chapter-1nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- C 4Dokument44 SeitenC 4nitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDokument10 SeitenUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- For 5 Buns of One Single ColourDokument7 SeitenFor 5 Buns of One Single ColournitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit-4 Lesson 11 PDFDokument10 SeitenUnit-4 Lesson 11 PDFnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soft Hawaiian Rolls RecipesDokument6 SeitenSoft Hawaiian Rolls RecipesnitakuriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Story of The SariDokument1 SeiteStory of The Sarirdhaimodkar10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Patternmaking For Fashion DesignDokument14 SeitenPatternmaking For Fashion DesignYonathan X Seyoum0% (3)

- Description About The Appearance of HumanDokument5 SeitenDescription About The Appearance of HumanLilianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Graduation Ceremony Guideline PDFDokument8 SeitenGraduation Ceremony Guideline PDFLoriemaehbadyosNoch keine Bewertungen

- STAR SCOUT CAMPORAL ACTIVITIES EditedDokument1 SeiteSTAR SCOUT CAMPORAL ACTIVITIES EditedvenusrecentesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presented By: Abhishek Sambhav FMS ROLL-02Dokument25 SeitenPresented By: Abhishek Sambhav FMS ROLL-02Varun MehrotraNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Report of H&M - Strategic MarketingDokument21 SeitenA Report of H&M - Strategic MarketingNikhil ChandranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nasar Hayat Major AssignmnetDokument17 SeitenNasar Hayat Major AssignmnetIslamic Video'sNoch keine Bewertungen

- LB170 نماذج ميدتيرمDokument62 SeitenLB170 نماذج ميدتيرمAmal SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 3 The PowerDokument3 SeitenJurnal 3 The PowerYonaJulia AprinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reliance Trend Store ProjectDokument9 SeitenReliance Trend Store Projectkiller dramaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Write My, Your, His, Her, Its, Our or Their. 2. Choose A or BDokument2 SeitenWrite My, Your, His, Her, Its, Our or Their. 2. Choose A or BMayra EriraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50+ Medium Length Hairstyles & Haircut Tips For Men Man of ManyDokument1 Seite50+ Medium Length Hairstyles & Haircut Tips For Men Man of ManyAditya KapoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teen Fashion Expression ArticleDokument2 SeitenTeen Fashion Expression Articleapi-588922852Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aquisition of Flipkart Group by Walmart Inc.Dokument13 SeitenAquisition of Flipkart Group by Walmart Inc.aniket kalyankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saree Heritage and Today's Indian WomenDokument5 SeitenSaree Heritage and Today's Indian Womensingh.swatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Through TimeDokument3 SeitenFashion Through TimeLeontina VlaicuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis SynopsisDokument5 SeitenThesis SynopsisPushkarani NNoch keine Bewertungen

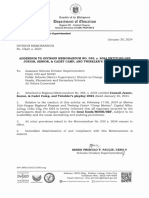

- 西e押rtm肌章O章⑲寄叫調t'叩: Division MemorandumDokument9 Seiten西e押rtm肌章O章⑲寄叫調t'叩: Division MemorandumAdela PandoroNoch keine Bewertungen

- PANTSDokument8 SeitenPANTSAlicia MyersNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03 AAU - Level 1 - Test - Standard - Unit 3Dokument4 Seiten03 AAU - Level 1 - Test - Standard - Unit 3PepiLopez50% (4)

- MainDokument32 SeitenMainHoang Minh AnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diplomatic Protocol.: CommunicatingDokument12 SeitenDiplomatic Protocol.: CommunicatingMika'il BeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adzurra Proposal 2017-07-08Dokument21 SeitenAdzurra Proposal 2017-07-08rayanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Draping: Created By-Pragati RastogiDokument17 SeitenDraping: Created By-Pragati RastogiPragati RastogiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CS&I - Chula Fashion Vietnam - Group 7Dokument9 SeitenCS&I - Chula Fashion Vietnam - Group 7Hue PhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnalysisDokument3 SeitenAnalysisXuân Đinh ThanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colour Guide - German Afrika Korps: Hints and TipsDokument2 SeitenColour Guide - German Afrika Korps: Hints and TipsMOMODD8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grooming Standard Novotel BJB PDFDokument28 SeitenGrooming Standard Novotel BJB PDFAriestya HandokoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mark CMontague CVDokument2 SeitenMark CMontague CVMark MontagueNoch keine Bewertungen