Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Organizing Value: Craig Prichard Raza Mir

Hochgeladen von

Craig PrichardOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Organizing Value: Craig Prichard Raza Mir

Hochgeladen von

Craig PrichardCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Editorial

Organization

17(5) 507–515

Organizing value © The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission: sagepub.

co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1350508410374242

http://org.sagepub.com

Craig Prichard

Massey University, New Zealand

Raza Mir

William Paterson University, Wayne, NJ, USA

Abstract

In this essay, we argue that the recent financial collapse, the ensuing recession and the work of key

social movements have created conditions for a reengagement of critically-inclined organizational

theorists with various forms of value analysis. We then introduce the seven articles in this special

issue and highlight how each makes a contribution to this reengagement.

Keywords

Exploitation, neoliberalism, value relations

‘Shoot the bankers, nationalise the banks’ was the simple headline in a Financial Times column

on 19 January 2009 (Stephens, 2009). Hardly the advice one expects from a serious newspaper

looking to recommend itself to the global business elite. But there it was. And it wasn’t flippant

or an entirely light hearted remark. Below the headline columnist Philip Stephens argued that UK

Prime Minister’s Gordon Brown was off the mark in suggesting that there was ‘rising public

anger’ over the behaviour of British banks. ‘Unbridled rage would have been a more accurate

description of public mood’, he said. There’s a sense that we may have been here before.

In his introduction to The Marx-Engels Reader, Robert Tucker suggests that Karl Marx ‘wrote

as though his pen were dipped in molten anger’ (Tucker, 1978: xxxviii). What propelled Marx’s

pen, Tucker argues, was his utter rage that seemingly reasonable economic theory and supposedly

civil society could justify the theft and alienation embedded in the wage–labour relationship. If

we take Philip Stephen as the emotional barometer of public discourse, it would seem that in the

last three years many have come to share the sentiment that drove Marx’s pen—and for much the

same reasons.

But how would critically inclined students of organization such as the readers of this Journal

explain such responses and what particular conceptual resources would they reach for in response?

Corresponding author:

C. Prichard, School of Management, Massey University PN214, Private Bag 11–222, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Email: c.prichard@massey.ac.nz

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

508 Organization 17(5)

Our field’s stock in trade analysis of organizing processes and practices has, in recent times, been

grounded in analysis of relations of meaning and power. Largely ignored, forgotten or ‘outsourced’

to conventional economic frameworks, has been earlier debate that drew on a third category—

relations of value.

The seven articles in this special issue are a response to this forgetting. Each presents analysis

and arguments that connect the political, symbolic and exchange moments of organizational

processes and practices. These articles offer various means of responding to the contemporary

context—a context reshaped over the last three years by financial collapse, recession and a parade

of various global social movements. Before introducing each article let us briefly turn to sketch in

the context.

As we write this introduction, more than a year has passed since the FT’s ‘Shoot the bankers,

nationalise the banks’ headline. Across Europe, entire economies have stalled as bankruptcy threatens

and public spending austerity measures have brought popular protests to the streets. Unemploy-

ment has reached a 20-year high in Britain and in the US the recession has put more than 8 million

people out of work, seen the loss of trillions of dollars in savings and put the country through what

President Obama described as a ‘great trial’. Large corporations have been seen as the forefront of

the crisis, epitomized by the news that the merchant banking firm Goldman Sachs (a name that may

well prove a liability in more straitened times) was facing both civil proceedings and criminal

investigation for possible double dealing.

Obama placed a significant portion of the blame for the financial collapse and the ensuing reces-

sion on financial institutions. In late April he told an audience not far from New York’s famous

financial district that: ‘A free market was never meant to be a free licence to take whatever you can

get, however you can get it. That’s what happened too often in the years leading up to this crisis.

Some—and let me be clear, not all—but some on Wall Street forgot that behind every dollar traded

or leveraged, there is a family looking to buy a house, pay for an education, open a business or save

for retirement’.1

One can appreciate Obama’s directness but what explanation is offered for this state of affairs?

The US President suggests that a kind of collective amnesia descended on some of these elite

financial firms. Some ‘forgot’ to maintain the expected principles of the ‘free market’ and some

forgot what lies behind every dollar traded and leveraged. The source of this value ultimately

lay in the energy, effort, labour and work of millions of Americans intent on pursuing the liberal

expectation of home ownership, higher education, business ownership and a financial secure

retirement.

One can appreciate the rhetorical poise of this explanation. It is an attempt after all to invoke the

need for more principled business practice and to prepare the ground for a new regulation of finan-

cial markets. A more problematic explanation would have it that this ‘forgetting’, this collective

absent mindedness, is at the very core of the neo-liberal economic regime that created the condi-

tions for the crisis and the recession (Boyer, 2001; Harmes, 2001; Harvey, 2005).

While the regime was financially built around the extension of cheap credit and a long housing

market boom, it centred ideologically on the social relations of the consumer as the primary locus

of responsibility over health, happiness and wellbeing. The ‘home’ that formed an important

element of this calculus was not a merely symbolic object in the formation of the family as institution,

or the social organization for the formation of primary social relations. It was an asset that could be

leveraged for a financial return. The upshot of this ideological construction was a kind of global

‘forgetting’ based on the social relations of the market.

Despite this situation, challenges to the neo-liberal regime have also come from other quarters.

Moving behind the banners of ‘fair trade’, ‘anti-globalization’, ‘global debt’ and more recently

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

Prichard and Mir 509

‘global warming’ or ‘climate change’, multiple groups and constituencies including farmers, small

business people and consumers have confronted world leaders, corporations and supra-national

bureaucrats over the equality and sustainability of flow of value in exchange relations. Alongside

direct action, such movements have along the way contributed significantly to broadening the

debate on ‘value’. These social movements have raised a counter ideological position that requires

the neo-liberal consumer to take an interest in the social, political, economic and environmental

genealogies of our food, clothing, shelter, technologies and energy use. In some cases, this counter

discourse has forced states, firms and individuals to reconsider organizing practices that simply

identify value in terms of monetary units, and have sought to broaden forms of value that are

understood to be exchanged in market relations. Market exchange relations are redefining them-

selves to incorporate political, social and ecological relationships between people, and between

people and their environments. In some instances, such work challenges institutionalized gover-

nance structures that organize the distribution of economic surplus—(see Reinecke’s empirical

analysis of the setting of fair trade prices in this volume).

The above discussion suggests that events of the last three years have significantly changed the

economic and political landscape across the developed western economies offering up for increased

contention their core organizing practices and processes. At the same time, popular movements

formed in response to neo-liberal economic and political ideology are forcing a re-examination of

how we conceptualize exchange relations. These shifts pose a problem as well as an opportunity

for critically inclined organization researchers, both to offer a counter-theoretical analysis of events

such as the economic crisis that militates against neoliberalism as well as to theorize the dissent of

working people against policies that continue to bail out the corporations that caused the crisis

while imposing harsh reductions in public spending on working people in the name of post-crisis

‘austerity’.

Re-engaging with value

In late 2008, as waves of fear and uncertainty over savings, jobs and businesses swept much of the

planet and governments scrambled to prop up failing economic institutions, a conference took

place in Wellington, New Zealand, under the title ‘Contemporary Critical Theories’. The event

brought together a number of organization theorists, and identified itself as a venue for ‘alternative

ways of describing, explaining, interpreting, understanding, and prescribing social, economic, and

political affairs’.2 The programme listed the following as possible approaches that would be wel-

come: ‘Deconstruction and Politics, Poststructuralist Political Theory, Perspectives in Discourse

Analysis, Philosophy of Social Science, Hermeneutics, Phenomenology, Critical Theory,

Psychoanalysis, Rhetorical Analysis, Postcolonialism, Feminist Theories and Practice’. What was

surprising was that despite the swirling economic crisis and the continuous conversation between

attendees about these events, neither the programme, the 26 articles presented at the event, nor any

of the critical theoretical resources recommended made any connection with the crisis.

This was not an isolated incident. A review of articles presented at the following year’s Critical

Management Studies Conference, EGOS Conference, or the Critical Management Studies Division

at the Academy of Management shows a similar pattern. The major economic events of the day and

the changing character of organized economic relations were mostly absent from the key gatherings

of the critically-inclined management and organization studies community. How is this possible?

Two explanations suggest themselves. First, our written work and our research is often ‘out of

date’. We study temporally dispersed practices and processes and are governed by lengthy publi-

cation and evaluation structures. These constraints often detach us from current events. Second and

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

510 Organization 17(5)

more concerning is the fact that such a separation is compounded by the increasing detachment of

critical organizational theorists from analysis of the economic relations. Gibson Burrell, one of the

founders of this Journal, once quipped that the field of organization studies had emerged as a result

of the successful subcontracting of the study of political and symbolic features of organizations

from economics. In other words, the problem is not with our organizing practices but with the

implicit ‘contract’ we appear to have made with our close disciplinary neighbour. Our ‘contract’

appears to carry an implicit veto on organizational analysis that links economic and political and

symbolic relations (see Marsden, 1999 and Rowlinson, 1997 for exceptions to this rule). Of course

the strengths of critically inclined organizational analysis has been found in its analysis of the

political and symbolic dynamics of organizing, while an analysis of how relations of power and

meaning, in/form and are in turn in/formed by exchange relations, that is, relations where value

flows between the positions (as energy, effort, income and surplus), have increasingly become our

Achilles heel.

That has not always been the case. Some of the original core texts of critical organizational

scholarship have been strongly informed by analysis of value relations. For instance Burrell and

Morgan’s study of sociological paradigms (1979) dedicated at least one of their two radical para-

digms to analysis that draws on Marxian analysis of exchange relations. Gareth Morgan’s best

selling textbook (1986) follows up the discussion of sociological paradigms with twinned chapters

that put the case for a Marxian analysis of capitalist crisis, and for organizations as instruments of

exploitation (chapters 8 and 9). Such work was not, of course, speaking from a hollow chamber.

It backed itself with work by the likes of Kenneth Benson (1977), Richard Brown (1978) Stewart

Clegg (1981) and Wolf Heyderbrand (1977).

Clegg’s ‘Organization and Control’ published in Administrative Science Quarterly in 1981 is a

central example of this strand of work. It offers a multi-layered conceptual framework that links

changing rates of capital accumulation with differential forms of control of an organization’s labour

process and the formation of organizational rules. The basic argument is that organizations are for-

malized around different rule sets. These rule sets are outcomes of historical moments that are

framed by particular rates of surplus value accumulation, different occupational structures and the

particular histories of inter and intra organizational conflict. In other words, the article offers a form

of analysis that connects wider accumulation patterns and particular relations of power. Clegg’s

article is a companion to his 1980 magnum opus with David Dunkerley, Organization, Class and

Control, and a prelude to a 1989 edited collection entitled Organization Theory and Class Analysis:

New Approaches and New Issues, all of which might be regarded as a high water mark for published

work that explicitly connects exchange and power relations. So what has happened since?

Almost 30 years from Clegg’s 1981 article, this concern with the interpenetration of value and

power relations but their analytical separation has largely disappeared. Such work appears to have

been subsumed, by our concern with identity, power and discourse. Ironically, discussions of value

creation and value appropriation are observed mostly in the realm of strategic management, where

its purveyors are scholars of neo-classically informed economic theory—particularly authors

representing the resource based view of the Firm (RBV). For example, both editions of the highly

successful Sage Handbook of Organization Studies handed the concern for the organization of

economic relations to RBV guru Jay Barney. Brief mentions of more critically inclined analysis are

made across this text but these are marginal and undeveloped. Writing in the concluding chapter of

the 1996 Handbook, Hardy and Clegg note,

the employment relationship of economic domination and subordination is the underlying sediment over

which organizational practices are stratified and overlaid, often in quite complex ways. (1996: 633)

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

Prichard and Mir 511

The assumption here is that while exchange relations are the underlying sediment of organizations,

they are subsumed into the political relations of domination and subordination and can thus be read

off from the latter.

In a similar vein, but a decade later, Willmott (2005) notes (in his presentation of Laclau and

Mouffe’s work as a form of organizational analysis), that

Workers, or wage labourers, participate in a relation of subordination to an employer, or capitalist, upon

whom they depend for their income. But this relationship is not antagonistic per se. It becomes antagonistic

only when the valency of the worker identity is subverted by some other identification. (2005: 770)

Like Clegg and Hardy, Willmott references exchange relations—workers are dependent on employers

for a wage—but this relation is analytically subsumed by the cultural/symbolic politics of

identification.

Is there a way to reverse this trend; to bring exchange relations and questions of value back to

the forefront of critical organizational scholarship? Let us return briefly to the issue of the economic

crisis. Organizational theorists need to get their hands dirty and join economists operating in the

critical tradition to offer a way out of the crisis, and to theorize ways in which working people can

make sense of the corporate malfeasance that brought this about. For instance, they could help link

the crisis to an increased pattern of inequality that began in capitalist societies in the late 1970s

(Alegretto, 2006). At a broader theoretical realm, they could explain esoteric corporate offerings

like synthetic collateralized debt obligations or credit default swaps through Marxian terms.

Vakulabharanam (2009) discusses how in the 19th century, Marx had presaged these instruments,

through reference to ‘fictitious capital’ in Chapter 29 (Components of Banking Capital) of Capital,

Volume 3, predicting that fictitious capital would intensify the problem of over-accumulation of

capital through the creation of asset bubbles. Of course, the creation of these asset bubbles happens

through the agencies of corporations, the very units of analysis that should be the stock in trade of

us organizational theorists. Likewise, we can shift the debate from a discussion of business ethics

to one of the nature of capitalism itself. The financial crisis of 2008 can be seen as a variant of the

crisis of overaccumulation (Bello, 2006). All these issues inexorably link back to questions of

value, of exchange relations and exploitation, terms that need to be rescued from the penumbra of

the consciousness of organizational researchers.

The point is not merely that organizational studies should focus on the economic crisis. The

broader point being made through this introduction, and the articles that comprise this special

issue, is that we organizational theorists ignore the issues inherent in regimes of value creation,

appropriation and distribution in society and in corporations at our own peril, and no amount of

reflection on issues of identity and power relations will offset the losses from this act of collective

shrugging on the part of the organizational researcher. This special issue is a small attempt to relocate

a few organizational debates back into the terrain of value.

Seven articles on value

The special issue comprises five full length articles and two shorter and more polemical ‘Speaking

out’ pieces. These two pieces by Adam Arvidsson and David Harvie and Keir Milburn present

contrasting forms of Marxian-inspired value analysis and offer strongly divergent visions of

contemporary capitalisms. The overall purpose of Harvie and Milburn’s piece is to illustrate how

value can be said to discipline, or organize, labour in contemporary capitalisms. Harvie and

Milburn draws on Diane Elson’s ‘Value Theory of Labour’ and shows how this approach allows

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

512 Organization 17(5)

us to consider value as both labour and that which is valued—sets of beliefs or commitments. Such

a categorization is then illustrated with a discussion of the managerial practice of benchmarking.

Arvidsson’s article, entitled ‘After Capitalism, Ethics?’, takes a quite different tack. For Arvids-

son western economies are in the midst of a thorough ‘crisis of value’. Such a crisis, which is in

part connected to the financial crisis and as a response to neo-liberalism, is created, more impor-

tantly, through a collective rediscovery of social production (aided and abetted by new forms of

electronic communication). Contra Harvie and Milburn, Arvidsson argues that labour in the con-

temporary period has overflowed efforts by capitalist relations of production to discipline it and

new relations of production, which Arvidsson calls ethical value, are creating the possibilities for

quite different economic structures.

The first of the five full length articles is ‘Creating “value” beyond the point of production:

branding, financialization and market capitalization’ and comes from Hugh Willmott’s keyboard.

This work picks up Arvidsson’s point regarding the importance of social production in the forma-

tion of value in contemporary capitalism. But rather than see new forms of social production as a

challenge to contemporary capitalisms, Willmott shows how this labour, the work of consumers in

this case, is valorized and privately appropriated through the development and valuation of brands.

The following article, from Juliane Reinecke deals with the politics of value distribution in a

commodity chain governed by novel price setting arrangements. Entitled ‘Beyond a subjective

theory of value and towards a “fair price”: an organizational perspective on fairtrade minimum

price setting’, the article draws on Reinecke’s ethnography of the Standards Committee of the

Fairtrade Labelling Organization (FLO). The article firstly offers a glimpse of the political process

of setting the price of the coffee trade under the Fair Trade labelling scheme, and then turns to the

challenge that such arrangements pose to conventional market processes. Reinecke suggests that

the key feature of this explicitly political price setting process is identifying common moral grounds

among the stakeholders upon which the negotiations of a fair trade price can proceed.

The political division of ownership in partnership structures is the topic of the next article. Pro-

duced by members of a Manchester Business School group lead by Julie Froud, and entitled ‘Own-

ership matters: private equity and the political division’, the article explores how claims on the

value realized by UK private equity firms are organized to favour general over limited partners.

Noting the popular resistance against private equity firms as owners of major public companies,

the article concludes by suggesting a number of policy options that flow from its ownership-based

analysis.

Resistance to the threat posed to local communities by Casino operators is the target of the next

article. Authored by Lynne Andersson and Lisa Calvano, and entitled ‘Hitting the jackpot (or not):

value extraction in Philadephia’s casino controversy’, the article provides a detailed analysis of

the conflict over the building of casinos in Philadelphia. Drawing on David Harvey’s accumulation-

based framework, the article brings to light the seductivity of neo-liberal discourse as the basis

for urban development strategies and the value commitments that form the platform for resistance

to this.

The final article in this special issue aims to make a critically-informed contribution to the

Resource-Based View of the Firm. Authored by Marlene Le Ber and Oana Branzei and entitled,

‘Towards a critical theory of value creation in cross-sector partnerships’, the article draws together

key strands of thinking from critical theories. Based on a standpoint approach and using the notion

of voice, the article then builds a socially critical framework for analysing the value distribution

aspects of cross sector partnerships. The article illustrates the framework with analysis of a series

of health sector partnership between firms and NGOs. The overall purpose of the work is to develop

theoretical frameworks that can deal with both social and economic objectives.

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

Prichard and Mir 513

Before closing this introduction we would like to recognize and thank the reviewers who read

and offered comments and suggestions on all the articles submitted to the special issue. Their

names are listed below in alphabetical order. Thank you!

• Boon, Bronwyn,

• Cederstrom, Carl

• Clark, Gordon

• Cooke, Bill

• Cronin, Bruce

• Dar, Sadhvi

• De Cock, Christian

• Dowling, Emma

• Fleetwood, Steve

• Gleadle, Pauline

• Gregory, Abigail

• Haski-Leventhal, Debbie

• Haslam, Colin

• Hewer, Paul

• Jaros, Steve

• Langley, Paul

• Levy, David

• Llewellyn, Nick

• Madra, Yahya

• Marens, Richard

• Marsden, Richard

• McKenna, Bernard

• Mohun, Simon

• Morgan, Glenn

• Muniesa, Fabian

• Murtola, Anna-Maria

• Power, Marilyn

• Pullen, Alison

• Rowlinson, Michael

• Sayers, Andrew

• Selsky, John

• Smircich, Linda

• Sotirin, Patricia

• Stablein, Ralph

• Stone, Melissa

• Teague, Paul

• Tomlinson, Frances

• Toms, Steve

• Warhurst, Chris

• Whitehead, Steve

• Williams, Karel

• Wright, Steve

• Zanoni, Patrizia

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

514 Organization 17(5)

Notes

1 Available from: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-wall-street-reform

2 Available from: http://www.victoria.ac.nz/criticaltheories/Conference.aspx

References

Allegretto, S. (2006) ‘Wealth Inequality is Fast and Growing’, Economic Policy Institute Snapshot. http://

www.epi.org/content.cfm/webfeatures_snapshots_20060823 (last accessed 5 May 2010).

Bello, W. (2006) ‘The Capitalist Conjunture: Over-accumulation, Financial Crises, and the Retreat from

Globalization’, Third World Quarterly 27(8): 1345–67.

Benson J. K. (1977) ‘Organizations: A Dialectical View’, Administrative Science Quarterly 22(1): 1–21.

Boyer, R. (2001) ‘Is a Finance-Led Growth Regime A Viable Alternative to Fordism? A Preliminary Analysis’,

Economy and Society 29(1): 111–45.

Brown, Richard Harvey (1978) ‘Bureaucracy as Praxis: Toward a Political Phenomenology of Formal

Organizations’ Administrative Science Quarterly 23(3): 365–82.

Burrell, G. and Morgan, G. (1979) Sociological Paradigm and Organisational Analysis. London: Heineman.

Clegg, S. (1981) ‘Organization and Control’, Administrative Science Quarterly 26(4): 545–62.

Clegg, S., ed. (1989) Organization Theory and Class Analysis. New Approaches and New Issues. Berlin/

New York: De Gruyter.

Clegg, S. and Dunkerley, D. ( 1980) Organization, Class and Control. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hardy C. and Clegg S. (1996) ‘Some Dare Call It Power’, in S. Clegg et al. (eds) Handbook of Organization

Studies, pp. 622–41. London: Sage.

Harmes, A. (2001) ‘Mass Investment Culture’, New Left Review 9: 103–24.

Harvey, D. (2005) A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heydebrand, Wolf (1977) ‘Organizational Contradictions in Public Bureaucracies: Toward a Marxian Theory

of Organizations’. The Sociological Quarterly 18(1): 83–107.

Marsden, R. (1999) Marx After Foucault. London: Routledge.

Morgan, G. (1986) Images of Organization. London: Sage.

Rowlinson, M. (1997) Organizations and Institutions. London: Macmillan.

Stephens, P. (2009) ‘Shoot the Bankers, Nationalise the Banks’, Financial Times, 20 January: 13.

Tucker, R. ( 1978) The Marx-Engels Reader. New York, NY: W. W. Norton and Co.

Vakulabharanam, V. (2009) ‘Recent Crisis in Global Capitalism: Towards a Marxian Understanding’, Economic

and Political Weekly 44(13): 144–50.

Willmott, H. (2005) ‘Theorizing Contemporary Control: Some Post-structuralist Responses to Some Critical

Realist Questions’, Organization 12(5): 747–80.

Biographies

Craig Prichard wrote his PhD at the University of Nottingham and his research and service work

contributes to the development of critical studies of management. He is the current Chair of the

Critical Management Studies Division of the Academy of Management, an Associate Editor of

the journals Management Learning and Organization and a Coordinator (with Deborah Jones)

of New Zealand’s OIL (organization, identity and locality) research network. He teaches critical

approaches to leadership, change and management knowledge for Massey University’s College of

Business in New Zealand and in 2010 he was awarded one of five Vice-Chancellor’s Awards for

Teaching Excellence. Address: School of Management, Massey University PN214, Private Bag

11–222, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

Prichard and Mir 515

Raza Mir, PhD, University of Massachusetts, is the Seymour Hyman Professor of Management at

William Paterson University in New Jersey, USA. He is also an Associate Editor of Organization.

His research mainly concerns the transfer of knowledge across national boundaries in multinational

corporations, and issues relating to power and resistance in organizations. He has published in

journals from a variety of disciplines, including Academy of Management Learning and Education,

Cultural Dynamics, Journal of Business Communication, Organizational Research Methods and

Strategic Management Journal. Address: Christos Cotsakos College of Business, William Paterson

University, 1600 Valley Road, Wayne, NJ 07470, USA. Email: mirr@wpunj.edu

Downloaded from org.sagepub.com at Massey University Library on February 6, 2011

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Granovetter - Economic Institutions As Social ConstructionsDokument10 SeitenGranovetter - Economic Institutions As Social ConstructionsPablo FigueiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Athens - Character Contests and Violent Criminal Conduct. A CritiqueDokument14 SeitenAthens - Character Contests and Violent Criminal Conduct. A CritiqueMaxCo69Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Politics of Value: Three Movements to Change How We Think about the EconomyVon EverandThe Politics of Value: Three Movements to Change How We Think about the EconomyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and ResistanceVon EverandConsequences of Capitalism: Manufacturing Discontent and ResistanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Political Anthropology of Finance: Studying The Distribution of Money in The Financial Industry As A Political ProcessDokument25 SeitenA Political Anthropology of Finance: Studying The Distribution of Money in The Financial Industry As A Political ProcessEstbn EsclntNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paul, David A. 1994. "Why Are Institutions The Carriers of History?: M10 Path Dependence and The Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions". Structural Change and Economic DynamicsDokument17 SeitenPaul, David A. 1994. "Why Are Institutions The Carriers of History?: M10 Path Dependence and The Evolution of Conventions, Organizations and Institutions". Structural Change and Economic DynamicsCarmela LedesmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipDokument44 SeitenThe Social Dimensions of EntrepreneurshipPablo SelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ngos, Civil Society and Accountability: Making The People Accountable To CapitalDokument30 SeitenNgos, Civil Society and Accountability: Making The People Accountable To CapitalbvenkatachalamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Corporate Governance and GlobalizationDokument22 SeitenCorporate Governance and Globalizationnishita MahajanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cowhey 1978Dokument4 SeitenCowhey 1978RhmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ethical Economy: Rebuilding Value After the CrisisVon EverandThe Ethical Economy: Rebuilding Value After the CrisisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rebiew Article-Economic Crisis and Mass Protest - Post Ad PansDokument3 SeitenRebiew Article-Economic Crisis and Mass Protest - Post Ad PansReinhard HeinischNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boyd - Political Economy of Alternative Models (M.lewis Highlighting)Dokument44 SeitenBoyd - Political Economy of Alternative Models (M.lewis Highlighting)thunderdomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wade, R. H. (2018) - The Developmental State Dead or Alive Development and Change, 49 (2), 518-546.Dokument46 SeitenWade, R. H. (2018) - The Developmental State Dead or Alive Development and Change, 49 (2), 518-546.tenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role of EnvironmentDokument22 SeitenRole of EnvironmentDivesh ChandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The IMF in Sociological PerspectivDokument25 SeitenThe IMF in Sociological PerspectivAweljuëc TokmacNoch keine Bewertungen

- 'Consumers' Co-Operation in Great Britain: An Examination of The British Co-Operative Movement'Dokument4 Seiten'Consumers' Co-Operation in Great Britain: An Examination of The British Co-Operative Movement'Ben RosenzweigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Development and Economic Growth Views and Agenda - Ross LevineDokument49 SeitenFinancial Development and Economic Growth Views and Agenda - Ross Levinedaniel100% (1)

- Has Globalization Gone Too FarDokument96 SeitenHas Globalization Gone Too Farleanhthuy100% (1)

- Financial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda: Journal of Economic Literature February 1997Dokument51 SeitenFinancial Development and Economic Growth: Views and Agenda: Journal of Economic Literature February 1997KelyneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Copie de WordDokument46 SeitenCopie de WordOumaima ElhafidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Derivatives and Deregulation. Financial Innovation and Demise of Glass-SteagallDokument56 SeitenDerivatives and Deregulation. Financial Innovation and Demise of Glass-SteagallLori NobleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bowman Narratives and Elite Power Trade AssociationsDokument24 SeitenBowman Narratives and Elite Power Trade AssociationsMarcelosarlingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mirowski, P. (1980) - The Birth of The Business Cycle. The Journal of Economic History, 40 (01), 171-174.Dokument5 SeitenMirowski, P. (1980) - The Birth of The Business Cycle. The Journal of Economic History, 40 (01), 171-174.lcr89Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Common Neoliberal Trajectory - The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced CapitalismDokument44 SeitenA Common Neoliberal Trajectory - The Transformation of Industrial Relations in Advanced CapitalismAna MaceoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fairclough 2014 What Is CDA Language and Power 25 Years OnDokument48 SeitenFairclough 2014 What Is CDA Language and Power 25 Years OnNayana MotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Performance Through TimeDokument11 SeitenEconomic Performance Through TimeFlorin-Robert ROBUNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anglo American CapitalismDokument26 SeitenAnglo American CapitalismJonathan Pang Peng HuatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven LeadershipVon EverandDeeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven LeadershipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wiley The Journal of Consumer Affairs: This Content Downloaded From 77.28.52.246 On Sun, 03 Oct 2021 04:36:52 UTCDokument4 SeitenWiley The Journal of Consumer Affairs: This Content Downloaded From 77.28.52.246 On Sun, 03 Oct 2021 04:36:52 UTCmichellechemeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Development, Growth and Poverty - How Close Are The LinksDokument32 SeitenFinancial Development, Growth and Poverty - How Close Are The LinksPrranjali RaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Capital TheoryDokument25 SeitenSocial Capital TheoryBradley Feasel100% (13)

- After the Flood: How the Great Recession Changed Economic ThoughtVon EverandAfter the Flood: How the Great Recession Changed Economic ThoughtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor in the Age of Finance: Pensions, Politics, and Corporations from Deindustrialization to Dodd-FrankVon EverandLabor in the Age of Finance: Pensions, Politics, and Corporations from Deindustrialization to Dodd-FrankNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The Handbook On Diverse Economies: Inventory As Ethical Intervention by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Kelly DombroskiDokument25 SeitenIntroduction To The Handbook On Diverse Economies: Inventory As Ethical Intervention by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Kelly DombroskiPlábio Marcos Martins DesidérioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bottom of The Pyramid Literature ReviewDokument4 SeitenBottom of The Pyramid Literature Reviewafmzjbxmbfpoox100% (1)

- The Global Economy: Organization, Governance, and DevelopmentDokument24 SeitenThe Global Economy: Organization, Governance, and DevelopmentKaye ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Markets As PoliticsDokument19 SeitenMarkets As PoliticsRodolfo BatistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2012 TerritorialisationDokument21 Seiten2012 TerritorialisationYongqi KeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 01: Name: Habib Ur Rehman Class: Bba 4A AssignmentDokument5 SeitenArticle 01: Name: Habib Ur Rehman Class: Bba 4A AssignmentHabib urrehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisis and Transition of NGOs in Europe - Petropoulos & Valvis - FinalDokument35 SeitenCrisis and Transition of NGOs in Europe - Petropoulos & Valvis - FinaluhghjghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jay W. Forrester - World Dynamics (Second Edition)Dokument161 SeitenJay W. Forrester - World Dynamics (Second Edition)RobertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Intermediation PDFDokument11 SeitenFinancial Intermediation PDFRodrigoBarsottiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phelps (2010) Capitalism vs. IsmDokument15 SeitenPhelps (2010) Capitalism vs. IsmKris HardiesNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Past, Present, and Future of Economics: A Celebration of The 125-Year Anniversary of The JPE and of Chicago EconomicsDokument208 SeitenThe Past, Present, and Future of Economics: A Celebration of The 125-Year Anniversary of The JPE and of Chicago EconomicsPower LaserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Euske and Euske 1991Dokument8 SeitenEuske and Euske 1991sandar_win1987Noch keine Bewertungen

- Occupy Connect Create 3.0 - ZineprintDokument20 SeitenOccupy Connect Create 3.0 - Zineprintsaskia_olivia295Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Post-Washington ConsensusDokument6 SeitenA Post-Washington ConsensuszakariamazumderNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Search of The Meaning of EntrepreneurshipDokument12 SeitenIn Search of The Meaning of EntrepreneurshiplibertadmasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blair Shareholdervalue 2003Dokument30 SeitenBlair Shareholdervalue 2003Anonymous o6OMUCkqdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Guidelines To Address Global Challenges: Lessons From Global Action NetworksDokument19 SeitenDesign Guidelines To Address Global Challenges: Lessons From Global Action NetworksAmir ZonicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claar-Klay - Economics in Christian Perspective (Review)Dokument15 SeitenClaar-Klay - Economics in Christian Perspective (Review)Chi-Wa CWNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Growth and Social CapitalERSA WP08 Interest-LibreDokument41 SeitenEconomic Growth and Social CapitalERSA WP08 Interest-LibreRafael PassosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - Management and OrganizationDokument22 Seiten1 - Management and OrganizationDang Nguyen0% (1)

- Rodrik D. Has Globalization Gone Too FarDokument96 SeitenRodrik D. Has Globalization Gone Too FarJucaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Network Forms of Organization PDFDokument22 SeitenNetwork Forms of Organization PDFJess OpianggaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boix Social CapitalDokument8 SeitenBoix Social CapitalMauricio Garcia OjedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legitimacy Dilemmas The IMF S Pursuit of Country OwnershipDokument21 SeitenLegitimacy Dilemmas The IMF S Pursuit of Country OwnershipAlexandros KatsourinisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chip Pitts CSR Legal Analysis Book Chapter 2 On The Business Case The Drivers of CSRDokument20 SeitenChip Pitts CSR Legal Analysis Book Chapter 2 On The Business Case The Drivers of CSRCPscribd2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Myth of Social Investing: Jon EntineDokument17 SeitenThe Myth of Social Investing: Jon EntineRanulfo SobrinhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sedacion:Dolor:DelirioDokument49 SeitenSedacion:Dolor:DelirioRamón Díaz-AlersiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Peasants Mughal AgrarianDokument17 Seiten8 Peasants Mughal AgrarianNAKSHATRA NAGAURIANoch keine Bewertungen

- My Reflection About Philippine LiteratureDokument5 SeitenMy Reflection About Philippine LiteraturePrescilla Ilaga100% (1)

- Samahan NG Manggagawa Sa HajinDokument129 SeitenSamahan NG Manggagawa Sa HajingwenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noli 2Dokument61 SeitenNoli 2Jay Ar OmolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing Part 1 Essay SamplesDokument8 SeitenWriting Part 1 Essay SamplesSandraGMNoch keine Bewertungen

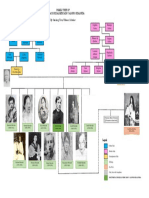

- Rizal's Family Tree (Senilong, Tare, Villamor, Salvador)Dokument1 SeiteRizal's Family Tree (Senilong, Tare, Villamor, Salvador)Sheen SenilongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burkett-Caraway First Draft EssayDokument13 SeitenBurkett-Caraway First Draft EssayPhyllis Burkett-CarawayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Zero-Ground of Politics: Musings On The Post-Political CityDokument18 SeitenThe Zero-Ground of Politics: Musings On The Post-Political CitypetersigristNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proceedings of Gen 75 Zoo LDokument902 SeitenProceedings of Gen 75 Zoo LCesar ToroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bangladesh The Next Generation 2015Dokument6 SeitenBangladesh The Next Generation 2015sabetaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumer AwarenessDokument21 SeitenConsumer Awarenessjagadeesh100% (1)

- MSC Agency India PVT LTD: Report On - "Identifying Reasons For Delay in Submission of Shipping Instructions"Dokument25 SeitenMSC Agency India PVT LTD: Report On - "Identifying Reasons For Delay in Submission of Shipping Instructions"AKSHAT JAINNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Capital-Special EUROBAROMETER N°223Dokument111 SeitenSocial Capital-Special EUROBAROMETER N°223BrasilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum For Community Radio Training in NigeriaDokument30 SeitenCurriculum For Community Radio Training in NigeriaHenry Anibe Agbonika I100% (1)

- (N.Feroze - Kandiaro) Overall PST ResultDokument171 Seiten(N.Feroze - Kandiaro) Overall PST ResultMuhammad YounisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Idoma Precolonial StateDokument4 SeitenIdoma Precolonial StateDANUSMAN HUSSEINA SALISUNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Chapter10Dokument113 Seiten1 Chapter10AlexHartleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ieee C135.61-2006Dokument15 SeitenIeee C135.61-2006lduong4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Words Are WorthDokument6 SeitenWords Are Worthy5me487Noch keine Bewertungen

- World Union of Jesuit Alumni/aeDokument8 SeitenWorld Union of Jesuit Alumni/aegmaskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CarnivalDokument16 SeitenCarnivalALISHARAISINGHANIANoch keine Bewertungen

- Houston Workshop D.authcheckdamDokument32 SeitenHouston Workshop D.authcheckdamAnonymous xifNvNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calamity Jane QA T VersionDokument5 SeitenCalamity Jane QA T Versionngla.alexNoch keine Bewertungen

- Winnie Berry Humane Society Volunteer Form 11-9-16Dokument2 SeitenWinnie Berry Humane Society Volunteer Form 11-9-16api-196425516Noch keine Bewertungen

- 16 10 24 10Dokument15 Seiten16 10 24 10bulletin3474Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tabela Golova JMC SMCDokument5 SeitenTabela Golova JMC SMCBranislav M PetrovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Resume 2Dokument3 SeitenNew Resume 2api-388126908Noch keine Bewertungen

- Particle-Size Analysis. IDokument28 SeitenParticle-Size Analysis. IMiguel Fuentes GuevaraNoch keine Bewertungen