Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Project Management For Development in Af PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jacques SavariauOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Project Management For Development in Af PDF

Hochgeladen von

Jacques SavariauCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PAPERS Project Management for Development

in Africa: Why Projects Are Failing and

What Can Be Done About It

Lavagnon A. Ika, Telfer School of Management, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada

ABSTRACT ■ INTRODUCTION ■

This article discusses international develop- ifty years after their independence, many African countries have seen

ment (ID) projects and project management

problems within ID in Africa and suggests they

may fall into one or more of four main traps: the

one-size-fits-all technical trap, the accountability-

for-results trap, the lack-of-project-management-

F their economies overtaken by those of countries that were worse off

in the 1960s. Ghana and South Korea had an almost equal per capita

income in 1957 (US$490). Just 30 years ago, China lagged behind

many African countries, including Malawi, Burundi, and Burkina Faso, on a

per capita income basis. Yet, approximately US$1 trillion of aid has been

capacity trap, and the cultural trap. It then pro- transferred to Africa since the 1940s (Moyo, 2009).

poses an agenda for action to help ID move At the dawn of a sixth decade of development aid, the enthusiasm of the

away from the prevailing one-size-fits-all proj- first years has given way to controversy and even disillusionment. According

ect management approach; to refocus project to aid proponents, it is working, albeit not perfectly, and a “big push”—more

management for ID on managing objectives for aid1—will surely turn things around in Africa (Sachs, 2005; Sachs et al., 2004).

long-term development results; to increase aid Opponents argue, however, that aid is not effective, as there is little good to

agencies’ supervision efforts notably in failing show for it (Easterly, 2006). Others argue that though aid may still be part of

countries; and to tailor project management to the solution, left alone it will fall short of addressing the needs of the “bot-

African cultures. Finally, this article suggests tom billion” (Collier, 2007). Still others argue that it is actually part of the

an agenda for research, presenting a number of problem or even the problem and thus it should be cut in half (Calderisi,

ways in which project management literature 2007) or even entirely (Moyo, 2009).

could support design and implementation of ID Though the heated debate among researchers and practitioners regard-

projects in Africa. ing the effectiveness of aid is still unresolved, two questions generally chal-

lenge authors and policy makers:

KEYWORDS: project failure; problems;

1. Macroeconomic perspective: Does aid contribute to international devel-

traps; international development projects;

opment (ID) in terms of growth and poverty reduction?

Africa

2. Microeconomic perspective: Do the projects and programs achieve their

specific objectives? (Hermes & Lensink, 2001; Lancaster, 1999)

In particular, the scant literature that considers whether ID project

success or failure primarily depends on countries’ political economy

(macroeconomic perspective) or project characteristics (microeconomic

perspective) fails to achieve consensus (Chauvet, Collier, & Duponchel,

2010).

Although both perspectives are complementary, the focus of most ID

research to date has been very narrow, examining projects and project man-

agement in general, despite the size of this industry sector (US$120 billion a

year in 2009), project proliferation, the importance of projects in the prevail-

ing program approach, and the questionable outcomes of projects (Ahsan &

Gunawan, 2010; Crawford & Bryce, 2003; European Commission, 2007; Ika,

Project Management Journal, Vol. 43, No. 4, 27–41 Diallo, & Thuillier, 2010, 2012; Roodman, 2006). Whether “more aid” (Sachs,

© 2012 by the Project Management Institute 2005; Sachs et al., 2004), “less aid” (Calderisi, 2007), or “dead aid” (Moyo, 2009),

Published online in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/pmj.21281 1In July 2005 at Gleneagles, the G8 summit committed to doubling aid to Africa.

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 27

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

whether they are funded by national carefully undertaken. In the design (European Commission, 2007; Ika et al.,

governments or international organiza- phase, the World Bank project supervi- 2010; JICA, 2006; World Bank, 1998).

tions, projects are still relevant in ID. sors advise government analysts with Many projects are thus implemented

Paradoxically, while the fields of regard to project definition, missions, in a managerially, economically, and

project management and ID date back and visions of the recipient country as politically different context from those in

to the 1950s and the 1960s, they have described in its national development developed countries. This is particularly

grown in parallel. ID has contributed to plan or poverty reduction strategy the case of ID projects funded by ID

the wealth of project management paper (see Ika & Saint-Macary, in press, agencies, especially multilateral ones,

knowledge, with logical frameworks, for the separation of roles between like the World Bank, the United Nations,

feasibility studies, and evaluations. World Bank project supervisors and and the European Union, and bilateral

Although project management has project managers). Hence, they ensure ones, like the United States Agency for

been heralded as a promising approach that policies, strategies, programs, and International Development (USAID), the

for ID (Stuckenbruck & Zomorrodian, project objectives are aligned (Ika & Canadian International Development

1987), underdevelopment in Africa has Saint-Macary, in press; Ika et al., 2012). Agency (CIDA), French Cooperation, and

worsened due in part to poor project Therefore, the design process many other governmental and non-

management (e.g., Eneh, 2009). begins at an abstract level of concepts governmental organizations. They deliv-

However, there is a gap in the literature (conceptual design), where the project er goods or services that are intended for

when considering the contribution of strategy and its strategic alignment with public use. These projects include small,

project management as a field of knowl- the program is envisaged. From this medium, large, and extra-large public

edge to ID (a few exceptions include point, it goes through a standard design projects and cover all sectors of develop-

Crawford & Bryce, 2003; Diallo & Thuillier, phase, where needs, problems, stake- ing countries in sub-Saharan Africa,

2004, 2005; Ika, 2005; Ika & Lytvynov, holders, constraints, options, feasibility, North Africa, the Middle East, Southeast

2011; Ika & Saint-Macary, in press; Ika and risks are analyzed, and ultimately Asia, Central and Latin America, and

et al., 2010, 2012; Khang & Moe, 2008). reaches a detailed design phase (i.e., a Central Europe. These sectors typically

This article examines the contribu- planning phase where the detailed include infrastructure, utilities, agricul-

tion of project management to ID. The project plan is created with estimates of ture, transportation, water, electricity,

contribution of this article is twofold. duration and cost, along with appropri- energy, sewage, mines, health, nutrition,

First, it aims at making ID projects more ate monitoring measures; see Ika & population, and urban development;

effective, and as such it suggests a num- Saint-Macary, in press; Ika et al., 2010; they also increasingly include education,

ber of ways in which project manage- 2012; Japan International Cooperation environment, social development, and

ment literature could support design and Agency [JICA], 2006). Once the World reform and governance (Diallo &

implementation of ID projects. Second, Bank project is properly designed and Thuillier, 2004, 2005; Youker, 2003).

its insights could be of benefit to project approved by the World Bank’s Board, it Consequently, ID projects share at

management literature, insofar as it enters the implementation phase. least some characteristics with stan-

looks at projects and project manage- Then, it is subject to strong and bureau- dard projects. In fact, they are generally

ment in the specific and emerging area cratic procedures or guidelines such as limited, temporary, unique, and multi-

of the expanding domain of project stringent reporting, monitoring, and disciplinary undertakings. They have a

management—ID. This article discusses evaluation requirements (e.g., Ika & life cycle, as they would typically evolve

ID projects, project management prob- Saint-Macary, in press; Ika et al., 2010). from the preparation phase to the

lems and traps in ID, and the potential con- Broadly speaking, projects and implementation phase, and to the eval-

tribution of project management to ID. project management have always been uation phase; they deliver goods and

present in the field of ID. The tradition- services as suggested above; they also

What Are International al approach to ensure that aid is spent face time, cost, and quality constraints;

Development Projects? properly is through projects. Despite a finally, like other types of projects, they

Let us start here with a typical and cur- shift since the mid-1990s from the long- require some specific tools and tech-

rent ID project funded by the World time prominent project approach to the niques for their implementation.

Bank. Since this falls under the program currently dominant program approach, However, ID projects differ greatly

approach, it is generally a subset of a project management is still important. from standard projects in the project

program or a long-term development Indeed, projects are relevant in devel- management literature and in practice. ID

plan (five to ten years). To ensure the oping countries with weak institutional projects connote the enactment of social

realization of project-specific objec- capacity, as a program approach would change in the life of poor people as well

tives, the design, implementation, mon- require that countries show some man- as a specific purpose, size, location, and

itoring, and evaluation of the project are agerial and organizational maturity timeline (Hirschman, 1967). They are

28 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

bound by a common goal of contribut- project management (IDPM),2 may be 2008). Diallo and Thuillier (2004, 2005)

ing to economic growth or poverty viewed as a subsector of general man- proposed a more complex network that

reduction. As such, they are generally agement aside the construction, engi- includes eight project stakeholders: the

not-for-profit projects. neering, information technology (IT), national project coordinator, who is

ID projects are altogether technical, education, health, telecommunica- the true project manager (also known

social, and political undertakings. They tions, manufacturing, defense, and as the national project coordinator/

are social because they aim to directly or other subsectors (Austin, 2000). As we director); the project team, whose

indirectly improve the wealth of the pop- have seen, ID projects are specific. leader is the project manager; the task

ulation, and political because the choice Therefore, their management is also manager of the ID agency (also known

of project options, such as locations or specific. Hence, a specific mode of proj- as the agency project supervisor or task

target groups, is often a political decision ect management prevails in ID, as its team leader); the national supervisor; a

made by ID agencies, donors, national use of project management approaches, steering committee; subcontractors

political leaders, and policymakers tools, and techniques is specific (Ika and suppliers of goods and services;

(Diallo & Thuillier, 2004, 2005). The lack et al., 2010, 2012). ID projects are fund- beneficiaries; and the population at

of market pressures and the intangibility ed by loans or outright grants, and the large. Ranasinghe (2008) suggested the

of project objectives make ID projects funding agency often leads identification grouping of ID project stakeholders

good targets for political manipulations of the projects and the determination of into four categories: those directly

as donors, and political leaders may their specific objectives (Youker, 2003). affected; those indirectly affected;

push for pet projects for political gains ID projects typically last from three government and public sector depart-

(Bokor, 2011; Khang & Moe, 2008). ID to five years, but the funding can be up to ments; and donors, consultants, man-

projects are, at the same time, ideas in ten years (Diallo & Thuillier, 2004, agers, and private businessmen.

response to perceived developmental 2005). ID projects are identified, pre- ID projects are generally managed

situational needs, income-generating pared, and implemented in a specific either by national and autonomous

activities, or investments with specified context (Diallo & Thuillier, 2004, 2005; project management units or by

economic returns and sequences of Youker, 2003). Under the prevailing pro- national departments. They may also

activities (see Ika & Hodgson, 2010; gram approach, typical ID projects be implemented by executing agencies,

Morgan, 1983; Rondinelli, 1983). would be part of a program and fit well including private companies or con-

Different types of ID projects exist. into comprehensive development sulting firms, nongovernmental organi-

They can be blueprint- or physical capital- frameworks (European Commission, zations, or partnering ID agencies. As in

based projects, or they can be process 2007; Youker, 2003). standard projects, the project manage-

projects or human-capital-based projects Project management in ID is ment unit mainly manages administra-

(Bond & Hulme, 1999; Hulme, 1995; Ika & confronted with demanding local con- tive processes. Project teams may be

Hodgson, 2010). Blueprint projects are straints and many stakeholders (Diallo & involved in procurement, organization,

infrastructure projects that include typical Thuillier, 2004, 2005). There are gener- and control of activities carried out by

ID projects in the 1950s and the 1960s or ally two categories of stakeholders for engineering firms, consultants, and

projects that must provide a package of standard projects and, in particular, subcontractors (Diallo & Thuillier, 2004,

goods and services for low-income benefi- for industrial projects: the clients, who 2005). ID projects typically follow trans-

ciaries, especially in rural areas as in the pay for the project and benefit from it, actional processes and strict guidelines

1970s. The process projects typical of and the contractors, who get paid by that are laid down by ID agencies to

the 1980s include projects like policy the client to implement a project and ensure that rigor and transparency are

advice, education, health, and institution- deliver expected results. However, ID maintained in the award of contracts

al building. ID projects may also be either projects require at least three separate and performance of tasks. Hence, the

hard or soft projects; they may be key stakeholders: the funding agencies, role of project supervisors or task man-

autonomous projects or projects as pro- who pay for but do not receive project agers is somewhat unclear, as they do

gram components (Ika & Hodgson, 2010). deliverables; the implementing units, not interfere with the day-to-day man-

ID projects may equally be systematic who are involved in their execution; agement of projects but are expected to

projects or emergency projects in post- and the target beneficiaries, who expect be updated on every step of projects;

disaster or post-conflict situations. some benefit from them (Khang & Moe, and project managers are encouraged

to request authorization with a “no-

Project Management in objection” from the former when it is

International Development 2Throughout this article we will use both project management

in international development (PM in ID) and international

time to proceed with major transactions

Project management in international devel- development project management (IDPM) interchangeably.

(terms of references, short lists, contract

opment, or international development Hence, PM in ID ⫽ IDPM. awards, etc.). When task managers do

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 29

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

not grant a no-objection, the reasons we will address in the next section of also the blog of the World Bank chief

may be that project teams have strayed the article (Ika & Hodgson, 2010). economist for Africa, Shantayanan

too far from guidelines (e.g., a bidder is Devarajan [2012], for an account of a

ineligible or lacks the qualifications to International Development few development success stories in the

undertake the assignment, or was pre- Project Management Problems continent.)

viously engaged in prohibited prac- and Traps But why do ID projects fail in Africa?

tices); there is inadequate planning of a Generally in ID, the poor performance In addition to the often heard com-

task; or nonconformance with project of projects is common, and the disap- plaints that Africa is the toughest part of

plans. And in such instances, project pointment of project stakeholders and the world for doing business and that

managers return to the drawing board beneficiaries seems to have become the Africa lacks highly qualified people

and repeat the whole process (Diallo & rule and not the exception in contem- (Dugger, 2007), we suggest that project

Thuillier, 2004, 2005; Ika & Saint- porary reality. But dissatisfaction with management in ID faces a range of prob-

Macary, in press). project results and performance dates lems and traps that would explain this

Overall, the unique environments back to the 1950s (see, for example, failure rate. We now turn to international

in which ID projects take place render John F. Kennedy’s speech to Congress in development project management prob-

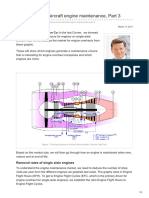

them very specific. ID projects are char- 1961). A recent McKinsey-Devex survey lems and traps. Figure 1 sketches three

acterized by high complexity and subtle- suggests that 64% of donor-funded key project management problem areas

ness, strong front-end activity, the relative projects fail (Hekala, 2012). The U.S. and four main project management traps

intangibility of their ultimate objective Meltzer Commission (2000) found that in international development.

of poverty reduction, a large array of het- more than 50% of the World Bank’s var-

erogeneous stakeholders, divergent ious projects fail. The Independent International Development

perspectives among these stakehold- Evaluation Group (IEG), in an inde- Project Management Problems

ers, the need for compromise, project pendent rating, claimed that in 2010, A number of problems undermine proj-

appeal in the eyes of politicians, the 39% of World Bank projects were ect performance in ID. They are described

profound cultural and geographical unsuccessful (e.g., Chauvet et al., 2010). as “the notorious and critical implemen-

gap between project designers and But how bad are the World Bank proj- tation problems,” some amenable to

their beneficiaries, the asymmetrical ects doing in Africa? change and others virtually intractable

distribution of power between the While the World Bank has invested (European Commission, 2007; Gow &

world’s richest countries, institutions more than US$5 billion in more than Morss, 1988; Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Kwak,

and people and its poorest, and the 700 projects in Africa over the past 20 2002). For some observers, geography,

prevalence of rather bureaucratic rules years (Dugger, 2007), its project failure bad governance, resource curse, and

and procedures (Ika & Hodgson, 2010; rate is over 50% in Africa, which is conflict bear a good share of harm (e.g.,

Ika & Saint-Macary, in press; Ika et al., greater than the 40% failure rate Collier, 2007, 2008). For others, lack of

2010, 2012; Khang & Moe, 2008; Kwak, observed in other poor regions of the project management capacity and poor

2002; Youker, 2003). Certainly, none of world and shows that African projects design are the culprits (see Williams,

these conditions are necessarily unique are lagging behind (Dugger, 2007). 2011, for the case of Nigeria). Still others

to ID projects and project manage- The World Bank’s private arm, the contend that it is “dirty” politics that

ment. In fact, we read more and more International Finance Corporation hurts development projects (see Bokor,

about complex projects in the standard (IFC), found that only half of its Africa 2011, for the case of Ghana). Consequently,

project management literature and projects succeed (Associated Press, 2007). many problem areas or checklists of

practice that experience a number of Many other agencies and donor coun- problems have been proposed in the lit-

these difficult conditions, whether they tries have not performed with much erature as serious obstacles to ID proj-

are national or international (e.g., more success (Associated Press, 2007). ects. For example, Rondinelli (1976)

Kerzner & Belack, 2010). However, Interestingly, the most successful offered a checklist of a “plethora of proj-

these conditions all together challenge World Bank projects in Africa have ect management problems” that occur

the contract-based precepts and been in infrastructure (e.g., railroads, most frequently (p. 11).

modus operandi of standard project ports, mobile telephone networks) as Here we suggest that project man-

management and prompt some to ask well as in the oil, gas, and mining agement problems in ID fall into

whether project management is a mis- industries; the weakest ones have been three main categories: (1) structural/

nomer in the field of ID (Ika & Saint- in manufacturing and banking contextual problems, (2) institutional/

Macary, in press). They also collectively (Dugger, 2007). (See Associated Press, sustainability problems, and (3) manage-

result in a specific set of problems fac- 2007, for a profile of a few development rial/organizational problems (European

ing project management in ID, which projects in Africa that went wrong and Commission, 2007; Gow & Morss, 1988;

30 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

outcomes, lack of implementation

capacity by donors and recipients,

Project Management (PM) Project Management (PM) Traps

Problems in International incompatibility between countries and

in International Development (ID)

Development (ID) donors’ management systems, overem-

phasis on highly visible quick results

from donors and political actors, and

risk of collusion between the principal

3 PM problem areas in ID: 4 PM traps in ID:

(agency bureaucrats or project supervi-

• Structural/Contextual • One-Size-Fits-All

Problems Trap sors) and the agents (project managers)

• Institutional/Sustainability • Accountability-for- with a double moral hazard at stake

Results Trap

Problems (a conflict of interest potentially detri-

• Managerial/Organizational • Lack-of-PM-Capacity

Trap

mental to the effectiveness of aid and

Problems

• Cultural Trap

an asymmetric information that ren-

ders difficult the evaluation of donors

and recipients countries’ activities).

Consequently, many project failures are

more institutional than technical

Figure 1: Why do projects fail? A diagram of project management problems and traps in international

development. (Eneh, 2009; European Commission,

2007; Gauthier, 2005; Gow & Morss,

1988; Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Ika & Saint-

Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Kwak, 2002; Structural/Contextual Problems Macary, in press; Martens, 2005;

Morgan, 1983; Rondinelli, 1976, 1983). Since ID projects are part of a broader Morgan, 1983; Rondinelli, 1983). This is

Let us turn here to the more recent US$4 context, they face serious problems that particularly the case of stand-alone or

billion Chad-Cameroon pipeline proj- may be political (contradictions autonomous projects that bypass local

ect and the US$3 billion South between the political agenda and the institutions only to break down budget-

Africa Medupi coal power plant project. development agenda of both donors ary, organizational, and managerial

Why did both projects fail? The answer and recipients), economic (resource structures in the aid-dependent coun-

to this question may be that the combi- constraints and macroeconomic policy tries (European Commission, 2007;

nation of the above three categories of concerns such as domestic price regula- Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Morgan, 1983;

problems has been detrimental to both tions and tight budgetary restrictions), Rondinelli, 1983; World Bank, 1998).

projects. More specifically, though the physical/geographic (climate, location, While both the structural/contextual

Chad-Cameroon pipeline project was flora, fauna, terrain, land, and natural problems and the institutional/sustain-

completed a year ahead of schedule in resources), sociocultural (religion, lan- ability problems may explain ID project

2003, it fails to deliver services to the guage, gender roles, and other culturally failures in Africa, the managerial/

poor, which were to be paid for by distinct traditions), historic (ethnic ori- organizational project management

the oil revenues—the Chadian govern- gins, patterns of collective action, colo- problems in ID also bear their fair share

ment used the latter to purchase arms nialism, and previous experience with of harm.

and military equipment (Calderisi, development efforts), demographic,

2007; Ika & Saint-Macary, in press). The and environmental (Collier, 2007, 2008; Managerial/Organizational Problems

South Africa Medupi coal power plant Gow & Morss, 1988; Kwak, 2002; Moyo, ID projects all too frequently fail to

project largely benefits major indus- 2009). However, awareness of these achieve their goals due to a number of

tries that consume electricity below structural/contextual problems is a first problems that are of a managerial/

cost but not the poor who bear a dis- step in their solution. While any of these organizational nature (Ika & Hodgson,

proportionate responsibility for sharing reasons may explain the poor showing 2010; Ika et al., 2012; Kwak, 2002).

the costs of the project, including nega- of ID projects in Africa, they do not tell

tive impacts on local communities near the whole story (Moyo, 2009). The paucity of well conceived proj-

ects is a primary reason for the poor

the mines (Bank Information Center,

record of plan implementation in

2012). Table 1 highlights the objectives Institutional/Sustainability Problems

many developing countries. The

of the two projects and the specific Institutional and sustainability problems inability to identify, formulate, pre-

problems that they have faced. The rest can include endemic corruption, capacity pare and execute projects continues

of this section discusses the three cate- building setbacks, recurrent costs of proj- to be a major obstacle to increasing

gories of problems that ID projects face ects, lack of political support and institu- the flow of capital into the poorest

in general and in Africa in particular. tional capacity to deliver sustainable societies. Despite more than a quarter

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 31

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

Specific/ Structural/ Institutional/ Managerial/

World Bank Overall Contextual Sustainability Organizational

Africa Projects Objectives Problems Problems Problems

The Chad-Cameroon Build a 1,000-km Chad is a landlocked Asymmetry of power Difficulties involving

pipeline project pipeline country at the heart of between project planners/ beneficiaries and

(US$4 billion) Reduce poverty and Africa with a history of implementers and taking their voices

improve Chad’s civil war and political beneficiaries into account

institutional violence that is faced with

capacity a resource curse (e.g., Lack of political and Escalation of World

60,000 children die of institutional capacity to Bank requirements

malnutrition every year) reduce poverty by delivering with regard to the

services to the poor, paid for environmental

by oil revenues (oil revenues assessment

were used by the Chadian

government to purchase Monitoring challenges

arms and military equipment) to ensure that oil

revenues would be

used to deliver ser-

vices to the poor

The South Africa Build a 4,800-MW coal- South Africa is one of the Asymmetry of power between Difficulties involving

Medupi coal plant fired power plant most energy-intensive project planners/implementers beneficiaries and

project (US$3 economies of the world and beneficiaries taking their voices

billion) Alleviate poverty and facing an electricity crisis into account

increase electricity since early 2008 (power The project largely benefits

access to the poor shortages and rolling major industries that consume Poor consideration

blackouts) due to demands electricity below cost rather than of health, water

for power exceeding supply the poor who suffer the negative scarcity, and pres-

environmental impacts of the sures on local ser-

project vices at the project

design phase

Source. Calderisi (2007) and Bank Information Center (2012).

Table 1: Why do projects fail? A glance at two mega-projects of the World Bank in Africa and their problems.

of a century of intensive experience badly due to poor design (Williams, coordination; monitoring and evalua-

with project investment, internation- 2011). Many project failures are thus tion failure; and others (Ahsan &

al funding institutions and ministries attributable to imperfect project Gunawan, 2010; Bokor, 2011; Diallo &

of less developed countries still report design; a blurred delineation of objec- Thuillier, 2004, 2005; Gow & Morss,

serious problems in project execution.

tives; an inadequate beneficiary needs 1988; Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Ika et al., 2010,

Many are due directly to ineffec-

analysis; an insensitivity of project 2012; Rondinelli, 1976; Stuckenbruck &

tive planning and management.

(Rondinelli, 1976, p. 10, emphasis

supervisors and managers to the needs Zomorrodian, 1987; Youker, 1999, 2003).

added) of beneficiaries; a lack of consensus on In summary, we argue first that

project objectives; differing and some- many project management problems

The remarkable thing about this what contradictory agendas among in ID would explain project failures and

quote on project management prob- stakeholders or even “dirty” politics; a that knowledge of them already exists.

lems in ID is that, almost four decades lack of project management skilled per- However, we suggest that project man-

after it was written, the issues it sonnel; poor stakeholder management; agement problems in ID fall into

describes actually stand out as a cur- delays between project identification three main categories: structural/

rent problem. In fact, many problems and start-up; delays during project contextual problems, institutional/

that were found to occur most fre- implementation; cost overruns; poor sustainability problems, and managerial/

quently are still harming projects and risk analysis; difficulties involving local organizational problems. We further

causing them to fail. That is the case beneficiaries due to literacy, distance, contend that while every one of these

with many Nigerian projects that fail and other communication problems; project management problem areas

32 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

may explain the poor showing of ID Although the concept of the devel- must follow no matter their size and

projects, they do not tell the whole opment trap has been around for a long content.

story. Accordingly, we submit that time, it remains controversial. Collier Not surprisingly, the current donor-

remedial actions that address the three (2007, p. 5) writes, “Development traps recipient paradigm requires rigorous

main categories of project manage- have become a fashionable area of aca- project plans and a robust toolbox to

ment problems, all together, can sub- demic dispute, with a fairly predictable the extent that there is an overemphasis

stantially improve project implementa- right-left divide. The right tends to deny on financial and technical feasibility at

tion as well as the chances for project the existence of development traps, the expense of social, cultural, environ-

success. asserting that any country adopting mental, and political feasibility (Ika &

However, ID projects are too com- good policies will escape poverty. The Hodgson, 2010; Rondinelli, 1976;

plex and the task ahead too challenging left tends to see global capitalism as Stuckenbruck & Zomorrodian, 1987).

to address all of these problems togeth- inherently generating a poverty trap.”

er: “Mankind always takes up such Despite this unresolved debate, this This prescriptive “one-size-fits all”

problems as it thinks it can solve” article is about four traps that have approach, also called the “blueprint

(Hirschman, 1967, p. 14, following Karl received little attention in project man- approach,” is most concerned with

“what should be done” rather than

Marx). Therefore, we argue, pragmati- agement in the ID industry sector:

“what does happen,” which repre-

cally, that there are project manage- the one-size-fits-all technical trap; the

sents a descriptive approach

ment traps that deserve the attention of accountability-for-results trap; the lack- (Analoui, 1989). Not surprisingly,

ID project decision makers and practi- of-project-management-capacity trap; the prevailing perspective of proj-

tioners and that breaking free of these and the cultural trap. We argue that ID ects is the planning view where

traps would help ID projects succeed. projects get caught in one or another of “a project is a planned complex of

the four traps, not to say all of them actions and investments, at a select-

International Development altogether. Projects are likely to fail ed location, that are designed to

Project Management Traps when they face such traps, and they meet output, capacity, or transfor-

The concept of a development trap is have to break free of them if they are to mation goals, in a given period of

not new. It dates back to the 1950s, as increase their chances for success. time, using specified techniques”

( Johnson, 1984, p. 112). Hence,

does the ID field itself (see Nelson,

the belief that project planning is the

1956). However, the concept of the The One-Size-Fits-All Trap

fundamental activity since there is a

development trap and its corollary, that Similar to standard project manage- need for a systematic way of “getting

of the poverty trap, have been most ment, project management in ID seems the job done” (Analoui, 1989; Ika,

recently associated with the works of to be dominated by a prescriptive, Diallo, & Thuillier, 2010). As a conse-

the economist Jeffrey Sachs, who has rational, and instrumental one-size-fits- quence, project analysts have

focused on how malaria and other all approach that is grounded in the tra- shared a deep conviction that ID

health problems keep countries poor. dition of fields such as engineering, project failure can be best

Sachs et al. (2004, p. 121) write, “Our architecture, and economics and that addressed by the use of better pro-

explanation is that tropical Africa, even assumes that all types of projects and cedures, tools and techniques

the well-governed parts, is stuck in a project models share the same charac- which would lead to more effective

IDPM, and thus, project success.

poverty trap, too poor to achieve robust, teristics (Baum, 1970, 1978; Ika et al.,

(Ika & Hodgson, 2010, p. 9)

high levels of economic growth and, in 2010; Ika & Hodgson, 2010; Johnson,

many places, simply too poor to grow at 1984; Picciotto & Weaving, 1994). As

all.” And Sachs (2005, p. 245) writes, noted in Ika and Hodgson (2010, p. 8), The Accountability-for-Results Trap

“The poor start with a very low level of “They (models) are normative or ideal; There is too much emphasis within aid

capital per person, and then find them- they rely upon logically ordered agencies on strong procedures and

selves trapped in poverty because the sequences of activities which are deter- guidelines, which leads to a culture of

ratio of capital per person actually falls mined by a known and explicit objec- “accountability for results” and of little

from generation to generation.” Even tive or set of objectives; they are rational attention to “managing for results.”

more recently, Collier (2007) highlighted since their objectives constrain the Project management in ID witnesses a

four traps from which countries have to analysis of options and risks; their plan- strong and bureaucratic procedures

break free if they are to develop: the ners are professional and, as such, are and guidelines orientation. Ika et al.

conflict trap, the natural resources trap, expected to act rationally, suppressing (2010, p. 82) writes, “The procedural

the trap of being landlocked with bad subjective considerations” (Hulme, aspects of project implementation may

neighbors, and the trap of bad gover- 1995). The World Bank, for example, has typically cover inter alia the format and

nance in a small country. standard procedures that all its projects the timing of disbursement and of project

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 33

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

funds reports, compliance with donor In 2007, the United Nations Develop- of those appointed (e.g., Dugger, 2007;

financial reports on how the money has ment Programme (UNDP) notes, “Results Gow & Morss, 1988; Ika et al., 2010).

been spent and how to apply for based management is seen mainly as a Project management in failed coun-

replenishment of project bank reporting regime, rather than a results- tries is no exception. Indeed, it often

accounts, and other statutory require- informed management regime” (p. 88). poses unprecedented challenges. Most

ments such as compliance with pro- Hence, there are a lot of incentives for failed countries in Africa (such as

curement guidelines.” project managers to spend a good deal of Burundi, Chad, the Democratic Republic

Furthermore, although results- time and effort on monitoring and eval- of Congo, Liberia, and Sudan) face severe

based management (RBM) as an uation; consequently, there exists a sig- challenges, such as a lack of institutional

approach and a tool has been around nificant correlation between the use of capacity, political instability, high vio-

in ID for more than a decade, it has monitoring and evaluation tools and lence, poor governance, destroyed basic

been too focused on reporting to exter- project “profile,”3 a success criterion infrastructure, devastated physical envi-

nal stakeholder audiences and too little that is an early pointer of long-term ronment, and pressing needs of scarce

on using performance information in impact (Ika et al., 2010). “Knowing how to resources and skills. Hence, aid agencies

internal management decision-making report and reporting on time is therefore face high costs and high risks (including

processes to achieve better results (Ika & of great importance” for project man- the security of their personnel) if they

Lytvynov, 2011). RBM has indeed two agers (e.g., Maddock, 1992, p. 405). choose to operate in such countries.

intended functions: an internal and an Aid agencies turn to projects

external. The Lack-of-Project-Management- instead of programs in failing countries

Capacity Trap with weak governance and poor poli-

When performance information is cies, but at the same time, under the

used in internal management Analysts have found that most pressure of efficiency to reduce their

processes with the aim of improving developing nations simply do not administrative costs relative to money

performance and achieving better have adequate institutional capacity they disburse, they reduce their super-

results, this is often referred to as or trained personnel to plan and

vision efforts; this harms the achieve-

managing-for-results. Such actual implement projects effectively. “In

use of performance information has

ment of the development goals and

one country after another,” former

often been a weakness of perfor- World Bank official Albert Waterston

objectives, notably in failing countries

mance management in the OECD contends, “it has been discovered where projects are known to be much

countries. Too often, government that a major limitation in imple- more likely to fail (Collier, 2007, p. 118).

agencies have emphasized perfor- menting projects and programs, and Failing states’ projects are more likely to

mance measurement for external in operating them upon completion, fail—or at best, less likely to succeed—

reporting only, with little attention is not financial resources, but if supervision costs money and aid

given to putting the performance administrative capacity. (Rondinelli, agencies such as the World Bank reduce

information to use in internal man- 1976, pp. 10–11, emphasis added) their presence to the bare minimum.

agement decision-making process-

es. (Binnendijk, 2000, p. 7)

What was true almost four decades The Cultural Trap

When performance information is

ago still remains. There is a lack of proj- The traditional top-down approach that

used for reporting to external stake- ect management capacity in ID. In fact, dominates development interventions

holder audiences, this is sometimes national governments and organiza- fails to take into account major decision

referred to as accountability-for- tions in Africa lack project management makers, fails to address the problem of

results. Government-wide legislation capacity and thus experience lack of rationality, and fails to account for the

or executive orders often mandate skilled personnel in project execution, lack of local commitment that leads to

such reporting. Moreover, such procurement, or monitoring and evalu- projects being considered “donor” proj-

reporting can be useful in the com- ation; shortages of project manage- ects rather than “local” projects (Ika &

petition for funds by convincing a ment–trained civil servants, delays in Hodgson, 2010; Youker, 1999, 2003). In

sceptical public or legislature that an

appointing personnel, or ineffective use particular, project management tools

agency’s programs produce signifi-

and approaches in ID have yet to be tai-

cant results and provide “value for

money.” Annual performance reports

lored or at least harnessed to the cultur-

may be directed to many stakehold- 3Please note that “profile” stands for a group of project al context of Africa (Ika et al., 2010;

ers, for example, to ministers, parlia- success criteria that include conformity of the goods and Muriithi & Crawford, 2003). Although

services, national visibility of the project, project reputa-

ment, auditors or other oversight there are few written resources for the

tion with international development agencies, and proba-

agencies, customers, and the general bility of additional funding for the project (Diallo & African project manager, cross-cultural

public. (Binnendijk, 2000, p. 7) Thuillier, 2004). project management issues as they

34 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

apply to Africa are common. In fact, the Contribution of Project He then argues that the Searchers do

current project management orthodoxy Management to International many useful things to meet the desperate

and the tools it proffers, such as the Gantt Development needs of the poor and thus find what does

chart, are rationality- and efficiency- More recently, Easterly (2006) called our work to help them. Finally, he suggests that

driven, and based on the Western attention to the debate between the losing as Searchers do not know the answers to

Greco-Roman philosophical premise “Planners” and the winning “Searchers” the big problems of development and that

that man is a rational being, which is in development aid. poverty issues are altogether political,

not always the case in Africa (Muriithi & social, historical, institutional, and techni-

Crawford, 2003; Rwelamila, Talukhaba, & Let’s call the advocates of the tradi- cal factors, they turn to individual, specif-

Ngowi, 1999). tional approach the Planners, while ic, and effective homegrown initiatives,

we call the agents for change in the

solutions, and projects, such as getting

alternative approach the Searchers.

Rwelamila et al. (1999) trace “the medicine to dying children.

The short answer on why dying poor

African project failure syndrome” Whether we are proponents of big

children don’t get twelve-cent medi-

back to the lack of a metaphor of plans or advocates of change in Africa,

cines, while healthy rich children do

group solidarity between African whether we are Planners or Searchers,

get Harry Potter, is that twelve-cent

project stakeholders coined “ubun- we may rely on project management to

medicines are supplied by Planners

tu” (harmony or literally translated

while Harry Potter is supplied by achieve our goals. That is why, even 25

“a person is a person”), which was

Searchers. This is not to say that years ago, project management was

due to an inappropriate traditional

everything should be turned over to hailed as “the promise for developing

project organizational structure.

the free market that produced and countries—the potential of the project

MIST cardinal principles, i.e.

distributed Harry Potter. The poorest management approach is so promising

Morality, Interdependence, Spirit of

people in the world have no money to

man and Totality . . . have proven to that, even though it must be drastically

motivate market Searchers to meet

be critical for PM in Africa. First, the modified or tailored to adapt to local

their desperate needs. However, the

belief that moral base is fundamen- cultures, it can be extremely important

mentality of Searchers in markets is a

tal to project success and the PM to the future of developing countries”

guide to a constructive approach to

must be committed to fair practices; (Stuckenbruck & Zomorrodian, 1987,

foreign aid. (Easterly, 2006, p. 5)

second, the belief that every project p. 174). Currently, Africa is replete with

stakeholder is part of the project suc-

numerous, sound, wonderful, brilliant,

cess formula; third, the belief that a He contends that Planners design big

captivating, impeccable, colorful, and

project is present to serve man with plans (e.g., Millennium Development

unconditional respect and dignity,

well-written development visions, poli-

Goals) to address big problems (e.g., the

and a failure to so condemns its cies, programs, plans, and projects (see

needs of the “bottom billion” poor peo-

existence; last, the belief that a PM Eneh, 2009 for the case of Nigeria, which

ple). He adds that Planners set forth big

system is made of a number of vari- accounts for one-fifth of the population

goals such as making poverty history

ables and that for it to be a success, of the African continent). Alas, most of

(Sachs, 2005; Sachs et al., 2004) but fall

it requires a number of improve- the bottom billion people are from Africa

ments from every internal client.

short when it comes to implementing

(Collier, 2007), underdevelopment is

(Rwelamila et al., 1999, p. 338, quot- these strategies through projects at a rea-

more about poor implementation of ID

ed in Ika et al., 2010, p. 83) sonable cost with the available means.

projects than lack of visions and pro-

How can the West end poverty in the

grams, and abandoned, failed, or poor-

Finally, although ID projects are Rest? Setting a beautiful goal such performing ID projects are common in

very specific and their environments as making poverty history, the Africa and often destroy its potential for

unique, remember that these problems Planners’ approach then tries to development (e.g., Eneh, 2009).

and traps are not entirely specific to design the ideal aid agencies, For that reason, project manage-

project management in ID; therefore, administrative plans, and financial ment has failed to deliver its promise to

we contend that the standard project resources that will do the job. Sixty develop and to meet the needs of poor

management literature may contribute years of countless reform schemes people in Africa. The development

to ID. Hence, ID project practitioners to aid agencies and dozens of differ- practitioners need to enhance project

ent plans, and US$2.3 trillion later,

may turn project management in ID management if they would like to make

the aid industry is still failing to

into project management for ID. We this promise a reality. To that end, we

reach the beautiful goal. The evi-

now argue how to address these project dence points to an unpopular con-

propose an agenda for action and an

management traps and discuss the clusion: Big Plans will always fail to agenda for research, draw on the

potential contribution of project man- reach the beautiful goal.” (Easterly, insights from the standard project

agement to ID. 2006, p. 11, emphasis added) management theory and practice, and

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 35

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

and interaction.” Context in general,

the type of project, the political situa-

tion, actors in presence, and the type of

A Tenfold Agenda for Research design, supervision, and implementa-

tion approach all matter (e.g., Ika &

International Development

Project Success Hodgson, 2010). Project management

approaches need to be tailored to these

A Fourfold Agenda for Action specific circumstances.

Breaking the Accountability-for-

Results Trap: Refocusing Project

Figure 2: An agenda for action and an agenda for research to address project management traps in Management for ID on Managing

international development. Objectives for Long-Term Results

Project management for ID should

refocus on managing objectives for

specifically suggest a few ways to Breaking the One-Size-Fits-All Trap: long-term development results and shy

address the project management traps Drawing Insights From Alternative away from its emphasis on visible,

in ID. In a nutshell, we suggest that Project Management Approaches short-term outcomes and efficiency. In

project management in ID, despite its Project management for ID should this regard, the internal function and

specificity, may learn a lot from the the- refrain from using the universalist one- use of results-based management need

ory and practice of project manage- size-fits-all approach and draw insights to incorporate big development goals

ment in conventional settings such as from alternative project management and key success criteria and factors into

construction and software manage- approaches, such as the eclectic contin- the design of ID projects for better

ment, which have had remarkable suc- gent and critical perspectives. One can- chances of project success (Ika &

cess owing to a methodical approach to not continue to overlook, ignore, or Lytvynov, 2011).

management, including some formal suppress the intrinsically political For example, a “management-per-

project management education for nature of projects in favor of an ideal- result” project design approach may

their project professionals and the use ized, apolitical, and neutral rationalism include Millennium Development

of some project management stan- (Ika & Hodgson, 2010). In that regard, Goals, key success criteria and factors,

dards (e.g., Hekala, 2012; Ika & Saint- hybrid and contingent models at the and “quick and dirty” cost-benefit esti-

Macary, in press). Hekala (2012) writes, midpoint between the traditional and mations. It calls on project designers to

“Hopefully in the future, donors will the political approaches, in which proj- focus their attention on the most

incorporate the collective knowledge of ects are both technocratic exercises and important level of project results for

decades of practice, millions of proj- political arenas for conflict, bargaining, which rough estimates of costs and

ects, and hundreds of thousands of pro- and trade-offs, in which data and tech- benefits are worth being known (see Ika &

fessionals in project management into nical tools, power, and skill are used to Lytvynov, 2011, for the “management-

their work, and then demand that those manipulate the agenda, to block a per-result” project design approach).

implementing projects they fund do potential item, or to withhold informa- The underlying idea is that one may

the same.” Figure 2 sketches a fourfold tion that does not suit the holder’s incorporate the “management-per-

agenda for action and a tenfold agenda needs are worth contemplating (Hulme, result” project design approach into the

for research to address project manage- 1995; Ika & Hodgson, 2010). project design component of RBM and

ment traps in ID. Bond and Hulme (1999, p. 1354) to align the expected project benefits

note, “The approach best suited to any with the Millennium Development

An Agenda for Action particular circumstance is dependent Goals under the prevailing program

Let us revisit the traps and see how

on the objectives of the intervention approach in the aid agencies (Ika &

they can be broken. To paraphrase an

and the specific context.” They further Lytvynov, 2011).

African proverb, the best time to

quote Johnston and Clark (1982, Such an approach could be comple-

address these four project management

pp. 23–28), “At the heart is the recogni- mented by the “potential impact”

traps was 20 years ago. The second-best

tion that the challenges of development approach, a technique that provides a

time is now.4

are not well-structured problems that simple and rough tool at the project

can be ‘thought through’ by clever peo- design phase that relies on the

4“The best time to plant a tree is 20 years ago. The second-

ple. Rather they are ‘messes’ that have to informed judgment of the planners,

best time is now” (Moyo, 2009, p. 155). be ‘acted out’ by social experimentation identification of key obstacles and how

36 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

removable they are, consideration of Supervision costs money: it comes formidable of these obstacles are cul-

whether the project would take place from the administrative budgets of tural ones, which are extremely dif-

without public investment, and any aid agencies. So an implication is ficult to do much about during the

that when agencies operate in failing lifetime of the typical project. In

external costs resulting from the proj-

states, they should budget for a addition, every developing nation

ect. It then compares potential impacts

considerably higher ratio of admin- has different cultural heritages

of alternative activities on the project

istrative costs to money actually dis- and customs, which must be

objectives in order to select the ones bursed. Of course, agencies are approached in very different ways.

with the greatest impact (Hubbard, under pressure to reduce their The project management approach

2000). Hence, one could improve proj- administrative costs relative to the must therefore be modified or

ect design and, consequently, the man- money they disburse; this is some- tailored in every way necessary to

aging-for-results function of RBM. times used as a measure of agency overcome these obstacles to the

Furthermore, instead of a strong efficiency. But it is misplaced. The use of project management.

procedures and guidelines orientation, environments in which agencies (Stuckenbruck & Zomorrodian,

aid agencies should move away from should increasingly be operating are 1987, p. 174, emphasis added)

those in which to be effective they

the constant pressure of demonstrating

will need to spend more on adminis- Almost 25 years later, although

results to a strong results culture where

tration, not less. Mismanagement of empirical evidence shows that Western

incentives for managing for results

bureaucratic performance is a gener- management concepts and approaches

(which include taking and not simply al problem. In aid agencies it encour- may not be universally valid, little

avoiding risks) are put in place. ages low-risk, low-administration insight is offered on how to adopt proj-

Otherwise, the aid agencies are too big operations that are the precise

ect management approaches, tools, and

and too bureaucratic to succeed. opposite of what they will need to be

techniques in Africa. Surprisingly, very

doing to meet the coming develop-

Breaking the Lack-of-Project- little has been written about project

ment challenges. (Collier, 2007,

Management-Capacity Trap: p. 118, emphasis added) management in Africa. African coun-

Improving Project Supervision tries may be more collectivist; they may

by Aid Agencies On the other side, aid agencies need have a higher power distance; they may

It is through supervision that agencies to include in their personnel more peo- score moderately on uncertainty avoid-

can ensure that development results ple with project management skills and ance and masculinity; and this may

are achieved. World Bank project super- academic background. Regrettably, the have implications for project manage-

vision, for example, has been assumed World Bank, for example, is still domi- ment in Africa (Muriithi & Crawford,

to be a global, generic, and multidi- nated by economists. Hence, most of 2003). What kinds of implications?

mensional project critical success fac- the ID professionals are “accidental” There may seem to be a strong need to

tor; furthermore, it has been shown project managers, as they hold project cope with political and community

that project supervision critical success and program management responsibil- demands on project resources and to

factors include monitoring, coordina- ities yet lack any formal project man- “sell the benefits” of the project to pow-

tion, design, training, and institutional agement education and background. erful hierarchies and stakeholders in

environment (Ika et al., 2012). Therefore, we strongly contend that order to minimize political interference;

In particular, it has been suggested donors should care more about project also, we see that while most project

that project supervision is even more management (Hekala, 2012)—and so management tools can work in Africa,

crucial for ID projects in postconflict/ should poor countries (Williams, 2011). attention should be paid to reward and

war situations; that the probability of recognition systems, particularly those

success of World Bank projects appears Breaking the Cultural Trap: Tailoring based on Western theories of motiva-

to increase as peace lasts; and that a Project Management Approach to tion (Muriithi & Crawford, 2003).

good implementation capacity is a crit- African Values and Culture(s) As these authors acknowledge

ical success factor for postconflict/ themselves, studies such as theirs are

war projects (Chauvet et al., 2010). Western management practices and welcome: “There is urgent need for

Surprisingly, aid agencies reduce their tools frequently fail because they do empirical work to: formalise a project

not achieve acceptance in the devel-

supervision efforts notably in failing management framework for Africa,

oping countries. Experience has

countries. confirm which tools and techniques of

repeatedly demonstrated that the

Project supervision efforts should the present management orthodoxy

implementation of such manage-

increase in aid agencies and notably in ment practices inevitably encounters work, which one does not and why, and

failing countries with weak governance formidable political, organizational, articulate an effective indigenous

and poor policies. and cultural obstacles. The most approach to project management in

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 37

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

Africa” (Muriithi & Crawford, 2003, project management would offer use- 2006), authors should address the

p. 318). ful methodologies, approaches, and alternative approaches to the pre-

Following these authors, we argue tools and techniques for ID (e.g., Ika et vailing universal approach to proj-

that there is a need for an African proj- al., 2010). To what extent might the ect management in ID (e.g., Ika &

ect management approach that is tai- nine Project Management Institute Hodgson, 2010).

lored to African values, cultures, and (PMI) Knowledge Areas and its 42 9. Considering the important role that

sociality. It has long seemed to us prob- project management processes apply NGOs play in ID, more studies are

lematic, and even embarrassing, that so to the specificity of ID projects? necessary to understand the concep-

many of Africa’s project management 3. There have been few empirical tions that these players hold on

problems should be studied by non- works on process projects (Bond & project success, success criteria, and

Africans, and non-African men in Hulme, 1999; Picciotto & Weaving, success factors and compare these

particular. Africa needs project man- 1994), and project success factors conceptions to the perceptions of the

agement specialists that address and such as flexibility, participation, aid agencies (e.g., Khang & Moe, 2008).

debate how to create or adopt project ownership, coordination, and har- 10. The question of learning in project

management concepts, tools, tech- monization of procedures deserve management for ID deserves atten-

niques, and approaches. their fair share of articles in the proj- tion and could shed light on the

ect management literature. experience of aid agencies in utiliz-

An Agenda for Research 4. Considering the increasing impor- ing project success factors in the

Ika and Hodgson (2010) have shown that tance of the RBM approach in ID, management of future projects

the same three approaches that describe there should be studies that address its (Biggs & Smith, 2003; Easterly,

chronologically and historically stan- potential contribution to project iden- 2007).

dard project management are insightful tification and design, and project/

in project management for ID, despite program success in ID (e.g., Ika & Conclusion

its specificity. Hence, it is possible to Lytvynov, 2011). This article explores the contribution of

describe and summarize project man- 5. In line with recent developments in PM to development in Africa. It is based

agement history in ID as moving from a the PM field on portfolio/program/ on four established facts: (1) the fields

traditional, instrumental, and monolith- project strategy (e.g., Artto, Kujala, of both project management and ID

ic approach better suited to blueprint Dietrich, & Martinsuo, 2008; Smyth, that date back to the 1950s and the

projects toward contingent approaches 2009; Srivannaboon & Milosevic, 1960s have grown in parallel, with very

that are better suited to process proj- 2006; Thiry & Deguire, 2007), the few attempts to bridge their divide

ects. Finally, this process points toward question of strategic alignment of or compare theories and practices;

the potential contribution of a critical programs and projects with larger, (2) more than 50 years after their inde-

approach that draws on broader criti- big-picture goals, such as the pendence, many African countries have

cal and postcolonial discourses to Millennium Development Goals, been overtaken in development by

embed the macro-political context in should be addressed. some countries that were worse off

our understanding of the operation and 6. More research is needed on ID proj- than they were in the 1960s; (3) approx-

impact of ID projects. ect success criteria and success fac- imately US$1 trillion of aid has been

Therefore, ID could learn a lot from tors and the interrelationships transferred to Africa with little good to

project management research, despite between the former and the latter show for it; and (4) whether they are

the recurring gap between theory and (e.g., Ika et al., 2010, 2012). funded by national governments or

practice. Here are a few research paths 7. In line with recent works on project international organizations, projects

that may deserve attention: sponsorship and the relationship are still relevant in ID.

1. The notion of project, under the new between project sponsors and man- As underdevelopment in Africa is

program approach orthodoxy (e.g., agers in the project management lit- more a result of poor implementation

European Commission, 2007; World erature (e.g., Bryde, 2008), studies than of a lack of big development goals,

Bank, 1998) needs to be revisited. should investigate the project and as poor performance of ID projects is

Project management for ID would supervision factor and address the pervasive, this article suggests that proj-

benefit from a systematic compari- collaboration between project ect management problems in ID would fall

son between project and project supervisors and managers in the into three main categories: structural/

management figures between proj- context of ID (e.g., Ika et al., 2012). contextual, institutional/sustainability, and

ect and program approach. 8. Considering the contribution of the managerial/organizational problems. As

2. If an ID project is, first and foremost, a critical theory to project manage- these problems are not entirely specific to

project, one could argue that standard ment literature (Hodgson & Cicmil, project management in ID, and as it is

38 August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj

impossible to address all these prob- living today—and in the future—on this from http://www.ghanaweb.com

lems together, this article calls for planet” (Rist, 2008, p. 258). ■ /GhanaHomePage/features/artikel.php

attention to be focused on four main ?ID⫽215290

traps that ID project decision makers

References

Ahsan, K., & Gunawan, I. (2010). Bond, R., & Hulme, D. (1999). Process

and practitioners have to break free of

Analysis of cost and schedule perfor- approaches to development: Theory

in order to increase the chances for

mance of international development and Sri Lankan practice. World

project success: the one-size-fits-all

projects. International Journal of Development, 27(8), 1339–1358.

technical trap, the accountability-for-

Project Management, 28(1), 68–78. Bryde, D. (2008). Perceptions of the

results trap, the lack-of-project-

Analoui, F. (1989). Project managers’ impact of project sponsorship prac-

management-capacity trap, and the

role: Towards a “descriptive” approach. tices on project success. International

cultural trap.

Project Appraisal, 4(1), 36–42. Journal of Project Management, 26(1),

This article then proposes an agen-

Artto, K., Kujala, J., Dietrich, P., & 135–151.

da for action to address these traps and

contribute to making ID projects more Martinsuo, M. (2008). What is project Calderisi, R. (2007). The trouble with

effective and efficient for the billion- strategy? International Journal of Africa: Why foreign aid isn’t working.

dollar investments in Africa. In doing Project Management, 26(1), 4–12. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

so, this article encourages a move away Associated Press. (2007, December Chauvet, L., Collier, P., & Duponchel, M.

from the prevailing one-size-fits-all 23). Examples of failed aid funded (2010). What explains aid project suc-

project management approach in ID to projects in Africa. Oil pipeline, fish pro- cess in post-conflict situations? (World

refocus project management for ID on cessing plant are a few of the unsuccess- Bank Policy Research Working Paper

managing objectives for long-term ful ones. Retrieved from http://www 5418).

development results, to increase the aid .msnbc.msn.com/id/22380448/ns Collier, P. (2007). The bottom billion:

agencies’ supervision efforts notably in /world_news-africa/t/examples-failed Why the poorest countries are failing

failing countries, and to tailor project -aid-funded-projects-africa/ and what can be done about it. Oxford,

management to African cultures. But if Austin, M. (2000). International devel- England: Oxford University Press.

the development practitioners are to opment project management. Paper

successfully address the chronic prob- Collier, P. (2008). Les performances de

presented at the Global Project

lems and traps that harm projects, they l’Afrique sont-elles les conséquences

Management Forum, London, England.

should learn from failure (e.g., Easterly, de sa géographie? [Africa: Geography

Bank Information Center (2012).

2007). Furthermore, this article sug- and growth. Is the performance of

World Bank (IBRD & IDA). Retrieved

gests an agenda for research (i.e., a Africa due to its growth?] Économie et

from http://www.bicusa.org/

number of ways in which PM literature Prévision, 186(5), 11–22.

en/Institution.5.aspx

could support design and implementa- Crawford, P., & Bryce, P. (2003). Project

tion of ID projects in Africa). This is our Baum, W. C. (1970). The project cycle.

monitoring and evaluation: A method

clarion call for overcoming or even Finance and Development, 7(2), 2–13.

for enhancing the efficiency and effec-

breaking the mostly economic “discipli- Baum, W. C. (1978). The World Bank tiveness of aid project implementa-

nary monopoly of development project cycle. Finance and tion. International Journal of Project

research at the World Bank” (Rao & Development, 15(4), 10–17. Management, 21(1), 363–373.

Woolcock, 2007) in order to help Biggs, S., & Smith, S. (2003). A paradox Devarajan, S. (2012). African successes:

projects succeed. So, let us welcome of learning in project cycle manage- Listing the success stories. Retrieved

development project (management) ment. World Development, 31(10), from http://blogs.worldbank.org

research! 1743–1757. /africacan/african-successes-listing

Finally, though this article aims to

Binnendijk, A. (2000). Results based -the-success-stories

contribute to making ID projects suc-

management in the development of co- Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D. (2004). The

ceed, this is admittedly just one part of

operation agencies: A review of experi- success dimensions of international

the development equation. Thus, we

ence (Background Report). development projects: The perceptions

hasten to admit that making projects

Organisation for Economic Co-operation of African project coordinators.

succeed may not be sufficient in mak-

and Development: Development International Journal of Project

ing development happen: “The point at

Assistance Committee Working Party Management, 22(1), 19–31.

issue is not the success or failure of this

on Aid Evaluation (DAC-EV).

or that ‘development project’ but a Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D. (2005). The

general way of envisaging harmonious Bokor, M. J. K. (2011). The dirty politics success of international development

and equitable cohabitation of all those of development project hurts. Retrieved projects, trust and communication: An

August 2012 ■ Project Management Journal ■ DOI: 10.1002/pmj 39

PAPERS

Project Management for Development in Africa

African perspective. International Hodgson, D., & Cicmil, S. (Eds.). Johnson, K. (1984). Organizational

Journal of Project Management, 23(3), (2006). Making projects critical. New structures and the development proj-

237–252. York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ect planning sequence. Public

Dugger, C. W. (2007, August 2). World Hubbard, M. (2000). Practical assess- Administration and Development, 4(2),

Bank finds its Africa projects are lag- ment of project performance: The 111–131.

ging. New York Times. Retrieved from “potential impact” approach. Public Johnston, B., & Clark, W. (1982).

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/02 Administration and Development, Redesigning rural development.

/world/africa/02worldbank.html 20(5), 385–395. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press.

Easterly, W. (2006). The white man’s Hulme, D. (1995). Projects, politics and Kerzner, H., & Belack, C. (2010).

burden: Why the West’s efforts to aid the professionals: Alternative approaches Managing complex projects. Hoboken,

rest have done so much ill and so little for project identification and project NJ: Wiley.

good. New York, NY: Penguin. planning. Agricultural Systems, 47(2),

Khang, D. B., & Moe, T. L. (2008).

Easterly, W. (2007). Are aid agencies 211–233.

Success criteria and factors for inter-

improving? (Brooking Global Ika, L. A. (2005). The management of

national development projects: A life-

Economic and Development. Working development assistance projects: Past,

cycle-based framework. Project

Paper 9). present, and future. Perspective

Management Journal, 39(1), 72–84.

Eneh, C. O. (2009, May 19–23). Failed Africaine, 1(2), 128–153.

Kwak, Y. H. (2002, September). Critical

development vision, political leader- Ika, L. A., Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D.

success factors in international devel-

ship and Nigeria’s underdevelopment: (2010). Project management in the

opment project management. Paper

A critique. Proceedings of the international industry: The project

presented at the CIB 10th International

International Academy of African coordinator’s perspective.

Symposium Construction Innovation &

Business and Development, International Journal of Managing

Global Competitiveness, Cincinnati,

pp. 313–320. Projects in Business, 3(1), 61–93.

Ohio.

European Commission. (2007). Ika, L. A., Diallo, A., & Thuillier, D.

Support to sector programs: Covering (2012). Critical success factors for Lancaster, C. (1999). Aid effectiveness

the three financing modalities: Sector World Bank projects: An empirical in Africa: The unfinished agenda.

budget support, Pool funding and EC investigation. International Journal of Journal of African Economies, 8(4),

project procedures. Tools and Methods Project Management, 30(1), 105–116. 487–503.

Series. Guidelines 2. Ika, L. A., & Hodgson, D. (2010, Maddock, N. (1992). Local manage-

Gauthier, B. (2005). Problèmes d’inci- January). Towards a critical perspective ment of aid-funded projects. Public

tation et aide au développement: Une in international development project Administration and Development,

perspective institutionnelle. [Incentive management. Paper presented at 12(4), 399–407.