Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Iso - Dis 2789

Hochgeladen von

Jelena JacimovicOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Iso - Dis 2789

Hochgeladen von

Jelena JacimovicCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

LIBER QUARTERLY, ISSN 1435-5205

© LIBER 2007. All rights reserved

Igitur. Utrecht Publishing & Archiving Services

ISO 2789 and ISO 11620: Short Presentation of Standards as Reference

Documents in an Assessment Process

by PIERRE-YVES RENARD

“Classifications are theories about the basis of natural order, not dull catalogues compiled only to avoid

chaos.” (Gould, 1989)

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this paper is to show how international standards dealing with library statistics and indicators (ISO 2789,

ISO 11620 and others projects which are still under development) can be used as reference documents and strategic

tools in a performance assessment process. The task is not an easy one, because it requires linking up somewhat

complex entities such as the standardization work characteristics, the capacity of statistics to account for reality and,

lastly, the variety and speed of libraries’ advancement. Nevertheless, ISO 2789 (International Library Statistics) and

ISO 11620 (Performance indicators for libraries), which are based on an international consensus of experts, take into

account, as much as possible, the recent evolutions in library structures and services. In addition, they are related to

classical and shared assessment models. So, although their aim is not to draw up an assessment framework, they reveal

themselves useful for basic operations in such a framework: to define objects and services, and to classify, count and

build appropriate indicators. Moreover, as the issue of quantifying and promoting intangible assets becomes a concern

in the public sector, these standards can be seen as a first attempt to define library resources and services as such

intangible assets. Finally, the challenge of forthcoming evolutions of these standards is the ability to stay up-to-date in

a very quickly evolving context. More precisely, the increase in the usability of these standards must be based on an

ongoing search for more consistent data and relevant indicators. The question of improvement of the general design of

the statistics and indicators standards family should also be addressed.

I would like to make three preliminary remarks about the tone of the paper, to prevent some (but not all) objections:

• An acknowledged naivety: I must recognize that there is a difference between reality as seen through the standards

and what really happens in libraries. For all that, is standardization really an armchair job, with no link to what

libraries experience daily? Certainly not, as I will try to demonstrate later on.

• An hypothesis of honesty: generally speaking, in the field of assessment, it takes two to play the game. There is

nothing easier than a misinterpretation of an indicator by an insincere authority. We measure indicators more to

ask questions than to give definitive answers, more to point out problems than to denounce a fault. Librarians

need to have in front of them managers sharing the same point of view on evaluation.

• A French context: some of my remarks will probably be related to the French context. France is a country where

public services and administration have a special place. We have a long tradition of public reports, made by many

high-skilled public auditing bodies, but we are only slowly developing a culture of assessment, in the Anglo-

Saxon sense of the word (without judging the cultural consequences it carries).

POSSIBILITIES AND LIMITS OF STATISTICS, EVALUATION AND STANDARDIZATION COLLATED

TO LIBRARIES’ REALITY

Certainly ISO 2789 and ISO 11620 are not used enough among the many existing tools in the field of library

assessment. However, the aim of this paper is not to present a very detailed description of standards, because the main

brake upon their implementation doesn’t seem to be a content issue but rather a perception issue. I would like to

present standards as living tools and not as boring directions for use or instructions, because they are no such things.

One can better understand the structure and content of the standards if the standardization work and its link with

libraries’ activity has been explained and made explicit. So I will mainly emphasize the context and the environment of

the conception and use of standards by noting the difficulty in harvesting statistical data or building useful indicators,

and the gap between how standardization works and the evolution of libraries.

The problem of data collection

I think we can agree that data harvesting in respect of library activity was easier yesterday than it is today (even if not

necessarily done). We used to have the possibility of knowing the users, who physically entered the library premises.

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

ISO 2789 and ISO 11620

The use of library resources could in many cases be calculated, as many books were kept in closed stacks, and because

the reader had to complete a form to access them. Most resources were concrete and printed materials, which can

easily be quantified, at least in meters. Today, users, resources and what the first do with the second, are not easily

described and defined. What some papers call ‘the library stuff’ is more and more precisely identified, but comes from

more and more online suppliers, so that gathering the data turns out to be a long and uncertain process. The general

word user covers a lot of different uses (or lack of uses) of the library services. At the same time, the need for data and

indicators for stakeholders and public decision makers is becoming more intensive and the pressure to demonstrate,

through numbers, the social utility of the library more acute. In other words, libraries are confronted by a ‘pincer-

effect’, the tension between a growing effort to build robust statistical information and the pressing demands of

accounting. The task is all the more problematic since there is still a discrepancy between what can actually be

measured and evaluated at a reasonable cost and what should be known about impact and mission fulfilment.

The gap between standardization work and library activities

Another source of confusion rests on the very characteristics of the standardization work. Standardization actually

requires time while libraries are currently evolving very quickly. It requires time because experts develop standards

besides their usual job, but also because standardization calls for international consensus, which is achieved through

many technical steps and cycles of drafts, ballots and comments. At the same time, libraries do not evolve towards a

consensus, but rather evolve in different ways, according to their size, their nature or their country. And finally,

libraries set up new services in an experimental way, having no time to wait for an innovation to be broadly adopted,

whereas a standard cannot be honestly published before it has been ascertained that its content meets a level of

confidence and stability compatible with its nature as an international reference document (even though standards are

voluntary). Standardization needs distance and feedback. Each performance indicator selected in ISO 11620 had been

tested before and constituted the subject of a paper in a professional journal: this was a criterion of validity from the

viewpoint of consensus.

TWO STANDARDS DESERVING OF WIDESPREAD USE

So, while we have seen that the development of assessment in libraries is recognized as strategic, the interest in having

standards at libraries’ disposal to organize certain steps of an assessment process does not appear to be obvious.

Apparently, it is obvious that interoperability issues can be dealt with by a standard or that identification numbers have

to be standardized, while the same perception is not necessarily made for statistical data and indicators. This is perhaps

because assessment is still seen primarily as a problem of good sense rather than a technical task. However, coming

back to some definitions could clarify the point that the status of ‘international standard’ can certainly be useful in

providing official technical guidelines, but also and above all to give a special weight to information collected with and

relied on by the standards. The French association for standardization, AFNOR, defines a standard as “a document

established by consensus and approved by a recognized body that provides, for common and repeated use, rules,

guidelines or characteristics for activities or their results, aimed at the achievement of the optimum degree of order in a

given context.” And also according to AFNOR, “the purpose of standardization is to provide reference documents

containing consensual and regularly updated solutions to technical and commercial problems relative to products,

goods and services that repeatedly arise in relationships between economic, scientific, technical and social partners”

(AFNOR, 2006, p.2). So a standard potentially fits the assessment purpose.

ISO 2789, A STANDARD FOR DEFINING, CLASSIFYING AND COUNTING IN LIBRARIES

40 years, 4 versions

ISO 2789 deals with a very precise sector in the galaxy of assessment: the definitions of data to be collected and the

way to present them. The fourth version was published in September 2006. The first edition dates back to 1974. It was

based on work begun at the end of the 1960’s by experts from IFLA and ISO, at the request of UNESCO, which

needed general guidelines for library statistics aggregation at an international level. The first version was only four

pages long and contained little information, of very general interest. Progressively the text has been improved and

extended (now almost 80 pages) so that it has become usable at smaller scales and by libraries themselves. The scope

of the standard being all libraries, the main difficulty has been to keep it valid through time at the different levels, for

internal purposes and for regional, national or international comparisons.

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

PIERRE-YVES RENARD

What you will find in ISO 2789?

Even if, in some ways, standardization and statistics trail after reality in libraries, there is an interest in trying to

establish a state of the art - what libraries are supposed to be and to do and the services they are supposed to deliver,

especially because the environment is changing very quickly. That is precisely the objective of ISO 2789, which tries

to give an almost physiological view of a library: what is it made of, which are the organs, what comes in and what

goes out? The role of such a document is important, because what you decide to count and the way you classify the

results says something about how you perceive the world (the library world in our case). Let me give an external

example showing that choosing the right data is a political sport. In 1889, in a Parisian atlas (Préfecture, 1889), the

level of well-being was estimated by the number of servants per family. That says enough about the way social

conceptions and technical or scientific options are intermixed.

To come back to libraries, how do we decide to define and count the different kinds of user? What do we decide to be

part of the library services and what not? How do we classify the different document delivery possibilities? Such

choices are strategic and express identity. ISO 2789 tries to answer these questions. Therefore, one of the important

sections of the standard - and perhaps the most important - is the definition section, because you can count correctly

only what you have precisely defined. ISO 2789 has, in its latest version, more than 100 definitions split up into 6

families: libraries (different kinds of libraries or administrative units), collections, use and users, access and facilities,

expenditure, library staff. The set of definitions is now very consistent and one can jump from one word to another

without meeting any incoherency. It is almost like a taxonomy, because you need to define every element precisely if

you want to avoid double counts and ambiguity. Up to a point, ISO 2789 could be used only as a lexicon: not a

roadmap, but a technical guide for certain situations.

After the definitions, the standard presents some general explanations on how to present data and the interest in

collecting them. The standard itself ends with a section detailing the data that can be collected, following the same

framework as the definition section. The main text is followed by three annexes, the first of which I would like to

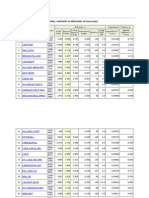

highlight. Use of electronic services (Figure 1) presents a clear classification of electronic library services and a small

set of data (sessions, downloads, visits), as they can be established today.

Figure 1: Electronic library services according to ISO 2789, Annex A

This is certainly not the only possible model, but the fact that it exists as part of an international standard is one thing

to its credit. Remembering the not so ancient discussions about what should or should not be counted among the

Internet stuff, to have such a stable document is a boon.

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

ISO 2789 and ISO 11620

ISO 11620, LIBRARY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS: SON OF ISO 2789?

From data to indicators

Having focused on the main aspects of ISO 2789, I will briefly present ISO 11620. The first version of this standard

was published in 1998, and a new one is about to be completed, incorporating amendments and elements from

technical reports produced in the interim (ISO, 2003-1 and ISO 2003-2). As for ISO 2789, recent disruptions in the

nature of information resources and changes in librarianship concerns made it difficult to achieve a stable and at the

same time up-to-date document.

Even if references are made to general performance models, ISO 11620 is, to my mind, still an extension of ISO 2789.

It does not tell one how to evaluate, how to assess performance, but how to make calculations in a performance

assessment process (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:The delimited area of action of ISO 2789 and ISO 11620

One explanation for this is that primarily, the ISO committee developing ISO 11620 is a statistical committee, opening

itself slowly but surely to assessment.

We must not forget that, in a logical management process, the main objectives are translated into operational actions

by the library, then indicators are defined, which must, once calculated, allow us to demonstrate whether the objectives

are met or not. The data have to be collected only when it is known which are needed for the indicators to be built. But

we know that libraries (and therefore the standardization) all began with statistics and counting before developing

assessment concerns. ISO 11620 bears the marks of such historical thought processes, and we chose to present the

standards accordingly, from statistics to evaluation.

From indicators to assessment

Although of statistical extraction, ISO 11620 is, as I said before, underpinned by some elements from classical

assessment models. Indicators described in the standard (and the ones which can be built according to the rules

described in the standard) can be judged against the traditional scheme, saying that performance is the conjunction of

effectiveness (results are in accordance with goals), efficiency (results are attained at a lower cost) and relevance

(means are adapted to goals). Another assessment reference lies in the way the proposed indicators are classified (and

this is a novelty in comparison with the previous version, where indicators were broken down in traditional

categories): the framework is adapted from a balanced scorecard approach whose headings are: resources, access and

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

PIERRE-YVES RENARD

infrastructure; use; efficiency; potential and development. The message sent to the users of the standard is that making

a good assessment does not imply a need to implement a lot of indicators: one must concentrate, for any given aspect,

on the impact, on what is really linked with performance rather than on the sole results. From this viewpoint, ISO

11620 is also a pedagogical tool.

In a nutshell, ISO 11620 explains how to build robust indicators and presents about 45 of them, precisely described

and analysed through a fixed scale: objective (of the indicator); scope; definition; method (to calculate, alternatives or

indirect method); interpretation and factors affecting the indicator; related indicators; sources (as each indicator has

been tested and published before). Each indicator must be compliant with a set of admissibility criteria: informative

content, reliability, validity, appropriateness, practicality, comparability (each term being explained in the standard).

ISO 11620 also includes language about the use of indicators, their selection, limitations, optimization or comparison.

Some supplementary definitions are also proposed, but most of those from ISO 2789 are applied, because of obvious

consistency concerns.

PRESENT RELEVANCE OF THE STANDARDS ISO 2789 AND ISO 11620 AND PATH FOR THE FUTURE

Basically, the first thing to be noted is that the standards do exist! Actually, if one considers the hard work they

represent and the quantity of information contained, combined with the difficulty of the standardization process,

finishing and publishing these two standards was not a foregone conclusion.

Secondly, they express what can be surely and clearly defined and calculated today. What lies in the future is not solid

enough to be standardized. Thirdly, as international standards, they give a real weight to the works which rely on them,

especially during political or budgetary discussions (or they should be used in this way). And finally, they offer a

common language (especially for international comparisons and in benchmarking projects): definitions, methods or

even indicators do not need to be re-invented each time for each new project.

A step forward

Nevertheless ISO 2789 and ISO 11620 could certainly be improved and complemented. New drafts are already being

(or are to be) developed, regarding statistics and performance assessment. One deals with performance indicators for

national libraries, given their special missions, which are not (correctly) covered by ISO 11620, and the other, if

accepted, could cover statistical issues for library buildings, planning and design. All things considered, these different

standards or drafts begin to look like a ‘family’, and maybe these family features could be reinforced by being better

and more explicitly organized, in the image of the ISO 9000 Quality Management Systems, for example. In the

medium-term, consideration may be given to merging the standards or to splitting them up into logical parts (general

reflections, definitions, collection of data, construction of indicators, etc.) This could facilitate the revision process

(especially with regard to the consistency of definitions) and improve the general visibility of these standards.

THE QUESTION OF INTANGIBLE ASSETS

To go further, I would like to tackle the question of intangible assets, which will be very important in the next few

years for libraries, and will be the area where statistics and assessment standards for libraries can contribute. The

‘intangible assets’ approach is an economic, legal and accounts concept where one tries to give a value to immaterial

assets that do not appear on the balance sheet traditionally: the trademark, the quality of the customer database, the

collective knowledge of scientists, and so on. It is also a new field for states, which are beginning to make a census of,

develop, promote and valorize their public intangible assets. For example, the right to use the Louvre trademark has

just been sold by the French state to Abu Dhabi for a period of years for M€ 400.

Generally speaking, the intangible assets approach is also a new way for states to consider their cultural national

heritage and the intellectual and scientific value of academic organizations. If they evolve correctly, ISO 2789 and

11620 could help libraries to measure themselves as sources of intangible assets and to demonstrate their involvement

in promoting intangible assets. Given some examples of intangible assets (staff skills, know-how, the content of public

databases and official publications, the quality of information systems) it is clear that some items at least can already

be converged with ISO 2789 or ISO 11620.

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

ISO 2789 and ISO 11620

CONCLUSION: BE IMAGINATIVE

The final aim of each assessment system and of the statistics and assessment standards for libraries also is to predicate

the answer to this (maybe impossible) question: what is the social impact of libraries? Three possible directions can be

considered for answering this question that the standards revision process must closely take into account: one would be

to succeed in producing an indicator which could account for social impact as a whole and which would be for

librarianship the equivalent of GDP (gross domestic product) or the consumer price index, quantifying the information

in a single number. Another direction is to keep working on more and more consistent indicators, related to specific

services and small groups of users, the sum of which would slowly but surely contribute to a progressively more

precise image of the social impact of libraries. The last direction is, of course, paying attention to users’ perceptions,

whilst keeping in mind that these can be considered only as a part of performance assessment, because meeting

individual needs does not mean that the social mission is fulfilled.

To conclude this article on ISO 2789 and ISO 11620, the promotion of standards and the development of their

usability, I would emphasize that it would be very interesting to consider a certification process. Certification is

certainly an attribute of standards, expanding their strategic strength from simple recommendation to competitive

argument. The possibility of officially acknowledging the compliance of library software with ISO 2789, or the

opportunity to certify quality programmes against ISO 11620 by recognized auditing bodies, may certainly be a

powerful lever for libraries. Placed before software vendors or policy makers it would allow libraries to better defend

their own assessment system of reference and not be required to meet only external and sometimes ill-adapted

performance criteria.

REFERENCES

AFNOR: The French Standardization Strategy: 2006-2010. Paris, 2006.

http://portailgroupe.afnor.fr/v3/pdf/strategystandardization_2010.pdf

Gould, Stephen J.: Wonderful life: the Burgess Shale and the nature of history. New York : W.W. Norton, 1989.

Préfecture de la Seine: Atlas de statistique graphique de la Ville de Paris. Paris, 1889.

WEBSITES REFERRED TO IN THE TEXT

AFNOR. – Association française de normalisation. http://www.afnor.org/portail.asp

IFLA - The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions. http://www.ifla.org/

ISO – International Organization for Standardization. www.iso.org/iso/home.htm

ISO 2789: 2006. Information and documentation - International library statistics

http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39181

ISO 11620: 1998. Information and documentation - Library performance indicators.

http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=19552

ISO 9000: 2005. Quality management systems.

http://www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=42180

UNESCO - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. http://portal.unesco.org/

http://liber.library.uu.nl/ Volume 17 Issue 3/4 2007

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Fracture Strength of Ceramic Monolithic Crown Systems of Different ThicknessDokument7 SeitenFracture Strength of Ceramic Monolithic Crown Systems of Different ThicknessJelena JacimovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fracture Strength of Ceramic Monolithic Crown Systems of Different ThicknessDokument7 SeitenFracture Strength of Ceramic Monolithic Crown Systems of Different ThicknessJelena JacimovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oral HealthDokument50 SeitenOral HealthJelena JacimovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science Citation Index Expanded - Dentistry, Oral Surgery & Medicine - Journal ListDokument17 SeitenScience Citation Index Expanded - Dentistry, Oral Surgery & Medicine - Journal ListJelena JacimovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 JCR Science Edition: Subject Category: DENTISTRY, ORAL SURGERY & MEDICINE (64 Journals)Dokument5 Seiten2009 JCR Science Edition: Subject Category: DENTISTRY, ORAL SURGERY & MEDICINE (64 Journals)Jelena JacimovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Unit 2 Progress Test A: GrammarDokument6 SeitenUnit 2 Progress Test A: GrammarMəryəm Əliyeva50% (2)

- Architecture - February 2021Dokument20 SeitenArchitecture - February 2021ArtdataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Intro To Children LitDokument32 SeitenChapter 1 Intro To Children LitJehhaira Dawag AlzateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alexander Riehle - A Companion To Byzantine EpistolographyDokument544 SeitenAlexander Riehle - A Companion To Byzantine EpistolographyMarka Tomic Djuric100% (2)

- 3 - Q4 Reading and Writing - Module 3 - RemovedDokument20 Seiten3 - Q4 Reading and Writing - Module 3 - Removedprincessnathaliebagood04Noch keine Bewertungen

- Piano Jack C., Olton Roy.-The International Relations DictionaryDokument476 SeitenPiano Jack C., Olton Roy.-The International Relations DictionaryLPPinheiro100% (3)

- Class III Holiday HomeworkDokument9 SeitenClass III Holiday HomeworkGURINDER SINGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Argumentative EssayDokument4 SeitenArgumentative EssaySalsa Zultin100% (4)

- Become A Superlearner Learn Speed Reading Advanced Memorization by Jonathan A Levi Anna Goldentouch Lev Goldentouch 0692416951 PDFDokument6 SeitenBecome A Superlearner Learn Speed Reading Advanced Memorization by Jonathan A Levi Anna Goldentouch Lev Goldentouch 0692416951 PDFAcharya PradeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Procedure TextDokument3 SeitenProcedure TextRagil Rizki Tri AndikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- B1 CHP 7Dokument12 SeitenB1 CHP 7JasmineVeenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Edtpa Lesson PlanDokument5 SeitenEdtpa Lesson Planapi-253343309Noch keine Bewertungen

- LIBROsrarosDEARTISTAAFRICANBOOK1038 - Nicholas Pounder 2012 PDFDokument85 SeitenLIBROsrarosDEARTISTAAFRICANBOOK1038 - Nicholas Pounder 2012 PDFMiriam LivingstoneNoch keine Bewertungen

- GRE Analytical Writing Book1 - 2022 - SampleDokument31 SeitenGRE Analytical Writing Book1 - 2022 - SampleVibrant Publishers0% (1)

- Graphic ArtsDokument29 SeitenGraphic ArtsДанилов АлинаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blueback-1 2021-11-16 06 43 49 Extract 2021-11-22 22 42 35Dokument10 SeitenBlueback-1 2021-11-16 06 43 49 Extract 2021-11-22 22 42 35api-313701922100% (1)

- Free Download Casing Liners Drilling Completion Guides BookDokument3 SeitenFree Download Casing Liners Drilling Completion Guides BookMansoor Ahmed Awan0% (1)

- Critical Study of Syllabus and Text Book (1) Atikur RahmanDokument12 SeitenCritical Study of Syllabus and Text Book (1) Atikur RahmanCool Boy100% (2)

- Tieng Anh de Thi Chinh Thuck23ma de 402 97202392224Dokument4 SeitenTieng Anh de Thi Chinh Thuck23ma de 402 97202392224Thư BùiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mls601 CDP Olopsc RodellpapaDokument8 SeitenMls601 CDP Olopsc RodellpapaRodellNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Matrix Method of Literature ReviewDokument3 SeitenThe Matrix Method of Literature ReviewVijay JoshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CMA P1 Plan A4 PDFDokument39 SeitenCMA P1 Plan A4 PDFsuresh nvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book SelectionDokument4 SeitenBook SelectionSakib StudentNoch keine Bewertungen

- MED300 Test 3Dokument3 SeitenMED300 Test 3Mark AdrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1A - SP Content English 2Dokument15 SeitenLesson 1A - SP Content English 2Neil ApoliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Fun They Had - Isaac Asimov: 1.how Old Are Margie and Tommy?Dokument2 SeitenThe Fun They Had - Isaac Asimov: 1.how Old Are Margie and Tommy?Candela OrtizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bed NotesDokument35 SeitenBed Notesamita_13raniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maria Montessori - The Montessori Elementary MaterialDokument523 SeitenMaria Montessori - The Montessori Elementary MaterialpinedavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Refactoring To PatternsDokument5 SeitenRefactoring To PatternsJeetendra KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blended Learning Across Disciplines Ichsan PDFDokument305 SeitenBlended Learning Across Disciplines Ichsan PDFSofie ChanNoch keine Bewertungen