Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Leading Across Cultures Requires Flexibility and Curiosity

Hochgeladen von

Armando Paredes0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten3 SeitenCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

10 Ansichten3 SeitenLeading Across Cultures Requires Flexibility and Curiosity

Hochgeladen von

Armando ParedesCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 3

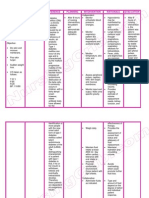

Leading Across Cultures Requires Flexibility and Curiosity

Deborah Rowland

MAY 30, 2016

How many nights have you spent in a hotel in a city

many miles from home? Perhaps nervous about the meeting in

the morning, you find yourself lying on the bed flicking

through the TV channels for something to watch to

keep you awake to offset the growing jet-lag.Automatically,

you search for channels and movies in your own language.

That’s a missed opportunity. Even without speaking the

local language, you can learn a huge amount about a

country’s culture from tuning into local television shows,especially

comedy programs. When I was heading Organization and

Management Development at Pepsi International,I would encourage

our international executives to study local comedy shows.Comedy

can be particularly hard to “get” if you’re not from the

originating culture, but that’s exactly why it shines a

light on how different cultures tick (“The Office,” which

was syndicated in some 80 countries but had localized

versions created in eight, is the classic example). It can

help you see the world as others see it.

Being able to tune into a culture without pre-conceived

biases or judgment is a skill all leaders need in

complex, global organizations. This was validated in my

most recent research into mindfulness and leadership, where it

emerged as the number one skill. The research involved

conducting and coding88 in-depth behavioral event interviews of

leading change with 65 leaders, spreadacross multiple

industries and from across five continents. My research team

and I were hoping to shed light on the skills that

made the biggest difference in leading across complex

global organizations. And being able to tune into a culture

and work with different world views stood out.

Fostering cross-cultural understanding takes dedicated effort.

Watching local TV is just one (fun) way to start. One

CEO I interviewed, the leader of an international charity,

went much further. She told me how she worked with her

colleagues from across 50 different cultures to be able to

see the world from each other’s perspectives. “We really engaged

with the local chief execs across the world to build mutual

trust and understanding,” she explained to me. “We started

meeting in each other’s homes every few months. We

traveled together. We all went to Uganda [one of

their key operations]. I did a job swap with my opposite

number in the U.S. There was quite a period of walking

in each other’s shoes.”

And yet while being willingto experience other cultures is

fundamental, at the same time you can never totally assimilate –

nor shouldyou. I found that successful global leaders also

keep a healthy level of detachment from the local culture

so that they can see its patterns clearly. Embracing

and understanding another culture can never mean ignoring

its ingrained habits. (This is true in company cultures

too, by the way, not just national or regional ones.)

Another executive I interviewed reflected on this. He

had intentionally used cultural difference to challenge and

change assumptions by tapping into local pride while remaining

non-judgmental. So while he understood the culture, he did

not blindly follow its diktats. His approach led to a

very successful turnaround of this country’s operation –

and all done without the local leaders feelingculturally

imposed upon.

“I think what wouldn’t have worked is the local approach

of being very downbeat and blaming others, as that

would have reinforced existing instincts. So I did the

opposite,” he explained. “I said, ‘Well, this is something we

can eminently fix. I’m sure there is plenty of peoplein

this organization who can help us do that. What we need to

first agree on is that we have a healthy future. And I’m

sure we’ll get there.’

“This caused a lot of surprise and, at first, a

reaction of, ‘Here’s another typicalWesterner, completely

naïve.’ But if you stay with that story, peopleactually start

believing you. And that’s where,quite quickly, it turnedaround.”

A way to make space for these different but complementary

approaches – empathetic non-judgment of the local culture,

while remaining slightly separate from it – is what I

describe as freedom within a framework. Essentially, you

come up with a metaphor that holds a global frame while

allowing for local adaptation. Let me give you an example.

I worked with one global leader at the oil company

Shell who united a disparate commercial fuels organization, spread

across almosta hundred countries, into what she described as

one “armada.” She used the metaphor of a fleet of

fighting ships — united in endeavor yet each havingto

fight their own local battles— as the unifying call to the

new global organization. She used pictorial Learning Maps to

communicate this vision to all staff (pictures are not only

worth 1,000 words,they also work better than words when you’re

communicating across language barriers). Moreover, she invited

each local culture to take the armada metaphor,

navigating choppy seas and battling against nearby

competitors, and translate that into a compelling story for

their own local context. They ran with it; for example, the

Asian region described themselves on their regional map as a

fierce fleet of dragon boats.

For the leader,the metaphor created a sharedlanguage —

but with different local translations. “I was in Oman last

week,”she told me when we met, “and I linked [my message]

back to the story of the ships, reinforcing simplemessages

about what it is we need to achieve… When you go

and visit peoplein the different cultures, you hear that

they’re talking about the same common agenda, and

beyond talking the same language, you get a real

sense that this was happening spontaneously.”

So, see the world as others see it, don’t completely

assimilate, and set a consistent framework within which local

cultures can adapt the story. And watch a little local TV.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Crowd Management - Model Course128Dokument117 SeitenCrowd Management - Model Course128alonso_r100% (4)

- Nursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1Dokument2 SeitenNursing Care Plan Diabetes Mellitus Type 1deric85% (46)

- Practical Econometrics Data Collection Analysis and Application 1st Edition Hilmer Test BankDokument27 SeitenPractical Econometrics Data Collection Analysis and Application 1st Edition Hilmer Test Bankdavidhallwopkseimgc100% (28)

- Rastriya Swayamsewak SanghDokument60 SeitenRastriya Swayamsewak SanghRangam Trivedi100% (3)

- Pre-Qin Philosophers and ThinkersDokument22 SeitenPre-Qin Philosophers and ThinkersHelder JorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fire and IceDokument11 SeitenFire and IcelatishabasilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tasha Giles: WebsiteDokument1 SeiteTasha Giles: Websiteapi-395325861Noch keine Bewertungen

- AQAR-Report 2018-19 Tilak VidyapeethDokument120 SeitenAQAR-Report 2018-19 Tilak VidyapeethAcross BordersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Os Unit-1Dokument33 SeitenOs Unit-1yoichiisagi09Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sensory Play Activities Kids Will LoveDokument5 SeitenSensory Play Activities Kids Will LoveGoh KokMingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motorola Phone Tools Test InfoDokument98 SeitenMotorola Phone Tools Test InfoDouglaswestphalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bob Jones: This CV Template Will Suit Jobseekers With Senior Management ExperienceDokument3 SeitenBob Jones: This CV Template Will Suit Jobseekers With Senior Management ExperienceDickson AllelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Azure Arc DoccumentDokument143 SeitenAzure Arc Doccumentg.jithendarNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMST 398 SyllabusDokument7 SeitenAMST 398 SyllabusNatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plato, Timaeus, Section 17aDokument2 SeitenPlato, Timaeus, Section 17aguitar_theoryNoch keine Bewertungen

- New York LifeDokument38 SeitenNew York LifeDaniel SineusNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5G, 4G, Vonr Crash Course Complete Log AnaylsisDokument11 Seiten5G, 4G, Vonr Crash Course Complete Log AnaylsisJavier GonzalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group Screening Test, English 6Dokument4 SeitenGroup Screening Test, English 6Jayson Alvarez MagnayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apache Nifi Tutorial - What Is - Architecture - InstallationDokument5 SeitenApache Nifi Tutorial - What Is - Architecture - InstallationMario SoaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- PWC - Digital Pocket Tax Book 2023 - SlovakiaDokument52 SeitenPWC - Digital Pocket Tax Book 2023 - SlovakiaRoman SlovinecNoch keine Bewertungen

- 33kV BS7835 LSZH 3core Armoured Power CableDokument2 Seiten33kV BS7835 LSZH 3core Armoured Power Cablelafarge lafargeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eps 400 New Notes Dec 15-1Dokument47 SeitenEps 400 New Notes Dec 15-1BRIAN MWANGINoch keine Bewertungen

- Plasterboard FyrchekDokument4 SeitenPlasterboard FyrchekAlex ZecevicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Holy Spirit Mass SongsDokument57 SeitenHoly Spirit Mass SongsRo AnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difference Between Dada and SurrealismDokument5 SeitenDifference Between Dada and SurrealismPro FukaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 3: Letters of RequestDokument4 SeitenLesson 3: Letters of RequestMinh HiếuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secondary Scheme of Work Form 2Dokument163 SeitenSecondary Scheme of Work Form 2Fariha RismanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3Dokument26 SeitenChapter 3Francis Anthony CataniagNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3250-008 Foundations of Data Science Course Outline - Spring 2018Dokument6 Seiten3250-008 Foundations of Data Science Course Outline - Spring 2018vaneetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minuto hd8761Dokument64 SeitenMinuto hd8761Eugen Vicentiu StricatuNoch keine Bewertungen