Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Health and The Human Spirit For Occupation: Elizabeth Yerxa

Hochgeladen von

Masayu Dinahya Diswanti0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

5 Ansichten7 SeitenOriginaltitel

412

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

5 Ansichten7 SeitenHealth and The Human Spirit For Occupation: Elizabeth Yerxa

Hochgeladen von

Masayu Dinahya DiswantiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 7

Health and the Human eilly's (1962) fundamental hypothesis "that man,

Spirit for Occupation R through the use of his hands as energized by

mind and will, can influence the state of his own

health" (p. 2) proposes a significant relationship between

engagement in activiry, as dictated by the human spirit

for occupation, and healthfulness. I shall explore that

Elizabeth J. Yerxa connection by describing my views of occupation and

health, sharing some assumptions, reviewing relevant

ideas from an array of disciplines, and drawing implica-

Key Words: chronic disease • health • human tions for occupational science and its application in occu-

activities and occupations pational therapy.

This article is based on my continuous search for

ideas from other disciplines, a synthesis of which may

contribute to the scholarly foundations of occupational

therapy (occupational science) and should therefore be

seen as a work in progress.

Views of Occupation and Health

The relationship between engagement in occupation and

healthfUlness is explored Health is viewed not as the ab- The human spirit for activiry is actualized, in a healthy

sence oforgan pathology, but as possession ofa repertoire of way, through engagement in occupation: self-initiated,

skills that enables people to achieve their vitalgoals in their self-directed activiry that is productive for the person

own environments. This sort ofhealth, reflecting adapt- (even if the product is fun) and contributes to others.

ability and a good quality oflife, is possible for allpeople, Occupations are organized into patterns or the "elemen-

including those with chronic impairments. tal routines that occupy people" (Beisser, 1989, p. 166).

Theoretical and research literature from an array of These activities of daily living (ADL) are categorized by

disciplines explores the influences ofoccupation on various our culture as play, work, rest, leisure, creative pursuits,

aspects ofhealth. These include interests, satisftction in and other ADL that enable us to adapt to environmental

everyday doing, balance, the latent consequences ofwork, demands. Dewey's (1910) criteria for a child's occupa-

and transcendence. Support is providedfor a relationship tion were that it be of interest, be intrinsically worth-

between activity level and survival. To improve the life while (relevant personally and socially), awaken curiosiry,

opportunities ofthose they serve, occupational therapists and lead to development. Engagement in occupation

need to become ardent students oflife's daily activities,

enables humans to learn competency.

grappling with the ambiguity and complexity ofoccupa-

I shall view health, not as the absence of organ pa-

tion, the occupational human, and the contexts in which

occupation takes place. thology, but as an encompassing, positive, dynamic state

of "well-beingness," reflecting adaptabiliry, a good quali-

ry of life, and satisfaction in one's own activities. Notice

that this perspective of health does not exclude persons

with disabilities. They may have irremediable impair-

ments but still possess the potential to be healthy, for

example, by developing and using skills to achieve their

vital goals (Porn, 1993).

What is the connection between engagement in

occupation and health? This question is crucial for

humankind in the new millennium, for the 21st century

will certainly usher in an unprecedented "era of chronici-

Elizabeth]. Ywca, EdD, LHD (Han), SeD (Han), OTR, FAOTA, is ry" due to advances in medicine's abiliry to preserve life.

Discinguished Professoc Emerita, Departmenc of Occupacion- What is thought about how people, including those with

al Therapy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, chronic impairments, achieve healthfulness through the

California. (Mailing address: Route 1, 196 Columbine, use of their hands, minds, and will?

Bishop, California 93514)

Assumptions

This article was acceptedfor pub/icati.on March 17, 1998.

I always urge my graduate students to make their as-

412 june 1998, Volume 52, Number 6

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

sumptions explicit, so I have to follow my own advice: too little attention to "work in solitude" as a source of

health and happiness. Two opposing motives operate

1. I shall view people as complex, multileveled (bio-

throughout life, one to bring us closer to people and

logical, psychological, social, spiritual), open sys-

another for autonomy. The second is as important as the

tems who interact with their environments (Kagan,

first.

1996) by using occupation to make an adaptive

Creative persons classed among the world's great

response to its demands. Consequently, human

thinkers often lacked close personal ties. For example,

beings cannot be reduced to a single level, say that

of the motor system, and retain their richness or Descartes, Newton, Kant, Nietzche, Kierkegaard, and

identity. Similarly, water cannot be reduced to hy- Wittgenstein lived alone for most of their lives, finding

drogen and oxygen and still be wet and drinkable. their chief value in the "impersonal" (Storr, 1988). The

2. The occupational therapy profession is founded on impersonal includes interest in doing almost anything from

an optimistic view of human nature (Reilly, 1962). breeding carrier pigeons to designing aircraft. Such interest

Occupational therapists discover a person's resources contributes to the economy of human happiness by fulfill-

and emphasize what that person can or might be ing the need for autonomy, leading to both adaptation

able to do instead of the person's incapacities; and creativity.

what's right instead of what's wrong. We are "search Storr (1988) criticized psychiatry and the social sci-

engines" for potential. Our profession is commit- ences for overlooking the importance of pursuing inter-

ted to improving life opportunities for all people, ests to meaning, happiness, discovery, creative contribu-

including those with so-called chronic impair- tion, and the human search for some pattern that makes

ments, a category that includes most of the per- sense out of life. Such pursuits can be a matter of life and

sons we serve. death. Acting on interests may prevent mental collapse

3. The postindustrial society is in danger of creating and subsequent death for persons in states of extreme

masses of throw-away people, a burgeoning under- deprivation. The capacity to be alone while pursuing one's

class whose chronic impairments, homelessness, unique interests is a valuable health resource, fulfilling the

mental illness, and inadequate education and skills need for autonomy and achieving personal integration

leave them outsiders in an increasingly technical, through activity one believes is worth doing. Interests

complex, and fast-paced society. In important energize occupation.

respects, most of society, except for an elite super-

class, may become an endangered species occupa- Satisftction in Everyday Doing

tionally. As Beisser (1989) said when he lost the

When I become discouraged by the high-tech, business-

ability to work as a physician due to paralysis, "My

oriented, specialist trajectory of our culture, I read Adolph

place in the culture was gone" (p. 167). Similarly,

Meyer (1931/1957). He never fails to revitalize my enthu-

for large segments of society, Rifkin (1995), an

siastic respect for the idea of occupation. Meyer (1922/1977)

economist, predicted the "end of work." Work as

focused on the person's everyday doings and actual experi-

we have known it may be replaced by a "technop-

ences as primary resources for health. Health was assessed

oly" managed by an elite class who keeps the robots

by one's relative capacity for satisfaction, "doing and getting

and computers operating, leaving millions without

enough" in those cycles of activity and composure that mark

a job or a place in society. This endangerment to

the rhythms of life. Meyer's (1931/ 1957) formula for satis-

health and well-being is profound because our soci-

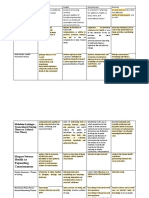

ety lacks an agreed-upon, valued substitute for faction included the components shown in Figure 1. His

work. Because we often view work as an economic view of satisfaction and health suggests major concepts

necessity rather than a biological, moral, and social for investigation by occupational scientists. For example,

imperative, we frequently fail to recognize the po- capacity implies that people be viewed as individuals who

tential impact of unemployment and loss of occu-

pational role on human health. The more than

70% of working-age persons with disabilities who PERFORMANCE AND MOOD

SATISFACTION =

are currently unemployed provides a window into

CAPACITY; OPPORTUNITY; AMBITION

the future (Bickenbach, 1993).

•= (in the light of) AVISION OF ULTIMATE ATIAINMENT

Relation of Engagement in Occupation to Health AND APPRECIATION BY OTHERS

Interests

Storr (1988), a British psychiatrist, proposed that our so- Figure 1. Formula for satisfaction (Meyer, 1931/1957, p.

ciety has overvalued intimate relationships while paying 81 ).

The American Jou,.naL ofOccupationaL Therapy 413

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

have unique skills and resources; opportunity requires they carry out their daily rounds of activiry. To be healthy,

attention to environmental qualities such as novelry, affor- people needed to be attuned to

dances, attractors, and challenges that will stimulate activ-

the larger rhythms of night and day. of sleep and waking hours, of

iry; and ambition involves energizers of action s~ch as hunger and its gratification and finally the big four-work and play

interest, curiosiry, will, desire, and personal perceptions of and rest and sleep which our organism must be able to balance even

skills. In interaction, these contribute to satisfaction by under difficulty. (p. 641)

influencing both performance (generating feedback) and

Meyer asserted that only by "actual doing" (p. 641) or per-

mood (encompassing one's being).

formance could this balance be obtained. Consequently, all

Meyer (1931/1957) placed this dynamic relationship

people needed to be provided with opponunities to work,

within a cultural context, showing that both other peo-

to achieve pleasure in their own achievement, and to learn a

ple's appreciation of what we do and our own expecta-

happy appreciation of time and the sacredness of the

tions of ourselves contribute to satisfaction. The formula

moment. This balance was learned through organizing one's

suggests that health may be influenced by discovering or

own actions.

developing new capacities, changing the environmen~,

Porn (1993), a contemporary philosopher, related

nurturing ambition, improving performance and modI-

health to people's ability to achieve their own goals

fying mood, all in ways appreciated by one's culture and

through engagement in daily life activities and routines.

acceptable to oneself. Meyer (1922/1977) proposed that

He viewed people as acting subjects (not reacting objects).

occupational therapists provide opportunities rather than

People, as actors, draw on three essentials: "a repertoire,"

prescriptions in the spirit of this formula.

an organized collection of abilities to act; an environment;

His formula applied to aLL people-physicians, psy-

and goals. Vital goals are personal objectives necessary for

chiatric patients, and the public. Thus, health via satisfac-

minimal happiness (p. 303). According to Porn, health

tion was possible for all, rather than requiring a special,

consists of achievement of a complex balance or equilibri-

separate track for those with psychopathology. Patients

um between people's environmental circumstances and

with mental illness were part of the mainstream of sociery,

the abiliry to realize their goals through a repertoire of

seeking the same satisfactions as anyone else, capable

abilities. Health is a kind of wholeness and general adapt-

thereby of influencing their own health.

edness that does not require freedom from pathology.

Meyer (1931/ 1957) saw potential everywhere; all

How could such healthfulness be assessed? We could

people possessed assets and capacities: "A st.udy and us~ of

look at the adequacy of one's repertoire (organized abili-

the assets, at the same time we attempt a dIrect COrrection

ties to act), the appropriateness of one's environment (es-

of the ills, is the first important condition of a psychobio-

pecially the opportunities it provides to, exercis~ abiliti~s),

logical therapy" (p. 157). But he was not blind to the

and the extent of realism in the persons goals In relation

challenge he posed: "To use the patient's assets is a more

to both the environment and the repertoire.

difficult problem than using something under our con-

How might health be fostered in a way that preserves

trol" (p. 157). Capabilities discovered and nurtured could

and defends adaptation? This might be accomplished by

overcome psychiatric problems, which he viewed as prob-

addressing the repertoire (e.g., developing new skills for

lems of adaptation.

increased competence), the environment by modifying its

Meyer's (19311 1957) optimistic view of people em-

challenges, and the goals by helping the person alter his or

phasizing their resources, capabilities, habits, and skills

her objectives. All three components need to be balanced

that enable them to adapt to their environments with joy,

for holistic care directed toward human agency.

satisfaction, and harmony places the spirit for occupation

Occupational therapists know this in their bones and

as central to human healthfulness. It is remarkable that

hearts. In Sweden, they participated in research that vali-

his philosophy was applied in the early 1900s, long before

dated Porn's (1993) theory between persons with and

the advent of psychotropic medications, because his pa-

without impairments. In this research, abiliry to achieve

tients must have exhibited severe symptoms rarely seen

one's vital goals (via a repertoire of skills) was found to be

today. Yet he viewed even these persons as capable of

more important to life satisfaction than degree of physical

healthy satisfaction through occupation.

impairment among those with stroke (Bernspang, 1987).

Other theorists who have related balance to health

Balance

include Csikszentmihalyi (1975), who posited the need

Activity. Many theorists whose ideas are relevant to occu- for a balance between self-perceived skills and environ-

pation and health propose the need for some sort of mental demands, and Reilly (1962, 1969, 1974), who

"healthy" balance. For example, Meyer (1922/1977) noted related health to a balance between degree of environ-

that people organize themselves in a kind of rhythm as mental challenge and capaciry for learning the skills, rules,

414 june 1998, Volume 52, Number 6

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

and habits necessary to fulfill occupational role expecta- The Latent Comequences ofWork

tions. Offering a "just-right challenge" that enables an

Recently a psychiatrist asked me, "Why is work so im-

adaptive response promotes a crucial balance for health-

portant to our patients? Why can't some other activity

promoting occupational therapy practice.

take its place?" Liebow's (1993) anthropological study of

Inftrmation. Klapp (1986), a sociologist, proposed

homeless women revealed their obsessive preoccupation

the need for another sort of balance concerning informa-

with looking for and finding a job. Our own research

tion and action. Today, health is threatened by the bore-

with men who had spinal cord injuries found that they

dom that permeates postmodern life, creating a thick

reserved the category of "work" almost exclusively for paid

cloud over people's everyday experience. We feel trapped,

employment, even though they were engaged in many

satiated, habituated, and desensitized because we are bom-

occupations that could have been called work (Yerxa &

barded by meaningless stimuli from the media, "noise"

Baum, 1986). How is participation in the apparently sig-

that requires no response. Listen to the monotonous, ever-

nificant occupation of work related to health as adapta-

urgent tones used by announcers and observe the sheer

tion?

volume of noise created by the endless commercials and

In technologically sophisticated societies, work is sep-

repetitious banality of the media. "Our ears are over-

arated from other activities, such as leisure. Relationships

whelmed while we are denied a voice," Klapp observed

that are largely based on work constitute a major source

(1986, p. 51). He defined information as "useful knowl-

of societal structure and order (Argyle, 1987). Work ap-

edge," contrasting it with "entropy" (p. 120), a tendency

pears to have a psychologically stabilizing effect on peo-

to randomness and confusion. When input does not

ple. Leisure, to be satisfYing in any important sense, needs

arouse interest but continues relentlessly, people often

to be viewed as the moral equivalent of work (Argyle,

escape into passivity or health-threatening "social place-

1972) to fill its culturally significant role. People who are

bos," such as alcohol, drugs, and other mood-altering

unemployed and have no organized leisure often become

addictions.

depressed, losing their sense of identifY and purpose in

The desired balance that buffers boredom and con-

life as well as their health.

tributes to health consists of "meaningful variety" that

Jahoda (1981) asked, why is work, as Marx observed,

encourages learning and "meaningful redundancy," which

such a fundamental condition of human existence that

is so familiar, reliable, and reassuring that it contributes to people eat to work, not the other way around? She differ-

warm memories and a sense of community (Klapp, 1986, entiated the "latent consequences" (p. 188) of work from

p. 118). (I think here of cultural rules and rituals.) People its manifest outcome of earning a living. Latency meant

need to develop skill to respond to this overload of mean- the unintended but significant "by-products" of being

inglessness by learning to view their boredom as a signal employed (p. 188). Five latent consequences of employ-

for action. To be healthy, they need to be taught to create ment seem relevant to health:

an individualized balance of meaningful variety and re-

dundancy through discovering, developing, and acting on • Employment imposes a time structure on one's day.

their own interests and by participating in the rules, hab- • Employment implies regularly shared experiences

its, and rituals of their cultures. and contacts with persons outside one's immediate

Meyer's (1922/1977) vision of providing opportuni- family.

ties rather than prescriptions, contributing to perfor- • Employment links persons to goals and purposes

mance and mood, offers occupation as an alternative to transcending their own.

this health-threatening imbalance. Instead of escaping • Employment defines important aspects of personal

into unhealthy social placebos to alter their moods, peo- status and identity.

ple could learn to achieve their own balance of meaning- • Employment enforces activity, providing a predict-

able demand for action. Qahoda, 1981, p. 188)

ful variety and meaningful ritual through engagement in

activity worth doing. Jahoda (1981) did not address the experience of "flow,"

Aristotle might have been right about the golden that autotelic satisfaction in simply doing the work (Csik-

mean. Health as adaptation, satisfaction, and quality of szentmihalyi, 1975), which is an important product for

life experience seems to require achievement of a desirable many people, nor did she discuss work's latent conse-

balance between environmental and personal attributes. quences for social units such as the family. However, her

Such a balance is highly individualized and is learned observations support the importance of work to health.

through opportunities to act on the environment as an Remove employment and yOli remove a person's strongest

agent. We need to learn much more about such healthy tie to reality (Freud, 1930), hls or her place in the culture,

balances and how they might be fostered. threatening healthfulness. Work is supportive of health

The American Journal ofOccupational Therapy 415

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

even under poor conditions. People may dislike their jobs, The manuscript of Frankl's first book was confiscated

bur they often dislike unemployment more (Argyle, 1987). when he was searched before incarceration. He felt this as

I still await the predicted utopia in which leisure be- a profound loss. His unfulfilled desire to rewrite the book

comes our major occupation. For leisure to be health not only helped him survive the rigors of camp life, but

promoting, it would have to convey the same latent con- working on it, reconstructing the manuscript, and scrib-

sequences as work. Instead, the laboratory of unem- bling key words in shorthand on tiny scraps of paper, also

ployed persons with impairments and others who have enabled him to ward off attacks of delirium. Engagement

lost their jobs due to corporate downsizing demonstrates in occupation, albeit mental, also enabled him to tran-

the stubborn significance to health and quality of life of scend his immediate disgust and despair. He visualized

having work worth doing. himself in a warm lecture room in front of an attractive

In many respects, the desire to engage in the occupa- audience. He was giving a lecture on the psychology of

tion of work and its significance to human health and the concentration camp. By so doing, he rose above the

happiness are not fully appreciated until the opportunity suffering of the moment. Occupation enabled him to

to engage is taken away, whether by revolutionary social objectify and describe his oppressing situation from the

upheaval, as in today's postindustrial, increasingly auto- "remote viewpoint of science" (Frankl, 1984, p. 95), trans-

mated society, or by the onset of impairment. Vash forming his emotions from despair into an interesting

(1981), a woman who was severely paralyzed by polio as a scientific study that he, himself, conducted.

teenager and later became a psychologist, put it this way: Extreme environmental degradation reveals the po-

"The impact of disablement is largely contingent on the tential transcending effects of occupation in stark clarity.

extent to which it interferes with what you are doing" (p. People were more likely to survive such conditions when

15), not only the actual activities, but also the potential they had interests and tasks worth doing and were able to

ones. Beisser (1989), who had been an ardent tennis create transcending experiences that restored their sense of

player and medical student before he contracted polio, autonomy (Frankl, 1984).

believed that "my place in the culture was gone" because

Relevant Research on Occupation and Health

he was no longer able to engage in the "elemental rou-

Hardy Personality

tines that occupy people" (pp. 166-167) and was discon-

nected from the familiar roles he had known in family, Kobasa (1982), an existentialist, believed that people con-

work, and spons. Yet the public, seeing Carolyn Vash struct a dynamic personality-"being in the world" (p.

and Arnold Beisser, would probably view inability to 6)-through their own actions. Because their life situa-

move as their most important characteristic, rendering tions are always changing, they inevitably encounter stress.

them "disabled." Important though such impairment is, She asked, how do people confront unavoidable stresses

preoccupation with the loss of motor control blinds us to and shape their lives successfully?

the signitlcant loss of something important to do, the frus- Her theory and research supported the idea of a

trated spirit for occupation, no longer served by their bod- "hardy personality" that resists stress and remains healthy.

ies, culture, or environment. Both of these articulate peo- (In contrast to my definition, she defined health as lack of

ple believed that this loss was more important than their physical or psychiatric symptoms.) The three characteris-

physical impairments. They echo Porn's (1993) theory of tics contributing to hardiness should interest occupational

health and Jahoda's (1981) latent consequences of work, therapists:

revealing the connection between engagement in occupa-

• Commitment-"ability to believe in the value of

tion and healthy adaptation.

who one is and what one is doing" (Kobasa, 1982,

p. 6) involving oneself fully in life, including work,

Transcendence

family, and social institutions. An overall sense of

The experiences of persons incarcerated under extreme purpose, goals, and priorities acts as a buffer to

conditions of deprivation and despair support the tran- stress.

scending effects of engagement in occupation that fosters • Control-"tendency to believe and act as ifone can

survival and sanity (Storr, 1988). Frankl (1984), a psychia- influence the course of events" (p. 7). Stress was

trist who lived through Auschwitz, stated: "In the Nazi viewed as a predictable consequence of one's own

concentration camps, one could have witnessed that those activity and subject to one's own direction.

who knew there was a task waiting for them to fulfill were • Challengf.'-a "belief that change rather than stabili-

most apt to survive" (p. 126). He reported that psychiatric ty is the normative mode oflife" (p. 7). Stress was

investigations into Japanese, North Korean, and North viewed as an opportunity or incentive rather than

Vietnamese prison camps reached the same conclusions. as a threat. Hardy people search for new, interest-

416 June 1998, Volume 52, Number 6

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

ing experiences and know where to turn for pate in life, skills that might influence survival itself.

resources. In another study (Wright, 1983), 100 patients with

severe disabilities underwent rehabilitation in a hospital

These three components contribute to "hardiness" or the

that encouraged their maximum participation. Patients

ability to resist stress and maintain health. Kobasa hy-

designed their own schedules and solved problems as they

pothesized that when life is stressful, people with such

arose. If a wheelchair needed repair, the patients worked

hardiness would remain healthy. Her hypothesis was sup-

OUt how to get it done. One year afrer discharge, these more

ported by research with male business executives, male

"occupationally autonomous" patients not only showed a

general practice lawyers, and female medical outpatients

greater degree of sustained improvement in aCtivities of

in retrospective and prospective studies, using subjective

daily living, but also a lower mortality rate than did the

and objective reports of illness indicators.

control group.

Kobasa's (1982) research conneCting commitment,

Both theory and research demonstrate that an envi-

control, and challenge to hardiness in the face of stress

ronment that provides opportunities for active engage-

supports the use of occupation as therapy to prepare peo-

ment in life contributes to health, well-being, indepen-

ple for engagement in the practical endeavors of everyday

dence, and survival. We need to take anOther look at the

life. For if Meyer (1931/1957) was correct that people

trivialization of occupation. What could be less trivial than

learn to achieve health in the doing, then such hardiness

survival?

may be learned and developed through engagement in

occupation. Gaining a sense of commitment in what one Conclusions

is doing, a sense of control over the course of events, and

An increasing body of knowledge from an array of disci-

the seeking of challenges as a source of interest are prod-

plines supports Reilly's (1962) great hypothesis. Humans

ucts of one's adaptive responses to a "just-right" degree of

can influence the state of their own health, provided that

challenge. In Kobasa's (1982) work, these products resist-

they are given the opportunity to develop the skills to do

ed the inevitable stressors of daily life and enabled people

so. The human spirit for occupation, developed through

to maintain health. The most important piece missing

eons of time in evolution, unfolding through develop-

from Kobasa's work is the process by which such character- ment, and actualized through daily learning, needs to be

istics are constructed by the person's actions in real life. I

nurtured to contribute to the health, quality of life, and

propose an important role for occupation. survival of persons and society.

Occupational therapistS and occupational scientists

Mortality

need to reaffirm that engagement in occupation, rather

In tOday's world, engagement in some occupations is of- than being trivial, is an essential mediatOr of healthy adap-

ten trivialized, sometimes considered merely diversion. tation and a vital source of joy and happiness in one's daily

This view may reflect our ignorance of the contribution life. In the new millennium, the era of chronicity and the

of engagement in occupation not only to health, but also potential "end of work" as we have known it will pose

to actual survival. particularly strenuous challenges: How can our profession

In an II-year study of the long-term survival of per- help create an environment in which people have oppor-

sons with spinal cord injuries, Krause and Crewe (1991) tunities to engage in the "moral equivalent of work" and

compared the characteristics of those still alive with those thus contribute to their own health? How can all people

known to have died. The researchers hypothesized that be provided with opportunities or "just-right challenges"

the survivors would have superior medical and psychoso- to discover their interests and potential for something

cial adjustment. "Medical adjustment" measured by non- worth doing?

routine medical appointments and hospitalizations, was Occupational therapy could promote a new concept

expected to be the most important predictor of survival. of health to replace the traditional view. Health, perceived

But neither recent medical histOry nor emotional adjust- as possession of a repertoire of skills enabling people to

ment predicted survival. Instead, strong suPPOrt was achieve their valued goals in their own environments,

found for a relationship between activity level and survival. would then be possible for all people, including those with

Those who were more active, vocationally and socially, in chronic impairments. A major objective would be to

participating in a round of daily occupations were more achieve "equality of capability" (Bickenbach, 1993). To do

likely to have survived. Activity level was more important this, we need to learn much, much more about how hu-

than medical history or a mediating emotional state. The man beings develop the adaptive skills, rules, and habits

authors, both psychologists, concluded that "counseling that enable competence as well as how occupational ther-

must go beyond facilitating emotional adjustment" (p. apists might create a "just-right environmental challenge"

84). Rather, people need to be taught the skills to parrici- to enable an adaptive response. Such "coaching" from

The Amaican journal o/Occupational Therapy 417

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

occupational therapists could benefit all people who need Frankl, V. (1984). Man's search fOr meaning (Rev. ed.). New York:

Washington Square.

to develop skills in order to survive, contribute, and achieve

Freud, S. (1930). Civilization and its discontents. London: Ho-

satisfaction in their daily life activities, whether or not they garth.

have impairments. Jahoda, M. (1981). Work, employment and unemployment:

To serve humankind well requires that we discover Values, theories and approaches in social research. American Psycholo-

much more knowledge about people as agents, in their gist, 36. 184-191.

own environments, engaged in daily occupations. We Kagan, J. (1996, January 12). Point of view: The misleading ab-

stractions of social scientisrs. Chronicle of Higher Education. XLII, p.

need to broaden our concept of ADL beyond self-care to

A52.

include study of the daily routines that occupy people in Klapp. O. (1986). Overload and boredom: Essays on the quality of

real life contexts. To learn what we need to know requires lift in the infOrmation society. New York: Greenwood.

that we accept the challenge of becoming ardent students Kobasa, S. (1982). The hardy personaliry: Toward a social psy-

of life's daily activities, grappling courageously with the chology of stress and healrh. In G. Sander & J. Sules (Eds.), Social

ambiguity and complexity of occupation, the occupational psychology ofhealth and illness (pp. 3-32). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Krause, J. S., & Crewe, N. M. (1991). Prediction of long term

human, and the contexts in which occupation takes place.

survival of persons wirh spinal cord injury: An II-year prospective

Only then will we fulfill our commitment to persons with study. In M. Eisenberg & R. Glueckauf (Eds.), Psychological aspects of

chronic impairments and assure that our humanistic val- disability (pp. 76--84). New York: Springer.

ues are expressed in an occupational therapy practice that Liebow, E. (1993). Tell them who I am. The lives ofhomeless

contributes to life opportunities and health for a new mil- women. New York: Penguin.

lennium. .A. Meyer, A. (1957). Psychobiology: A science ofman. Springfield, IL:

Charles C Thomas. (Original work published 1931)

Acknowledgments Meyer, A. (1977). The philosophy of occupation rherapy. Amer-

A major portion of this article was presented as the Wilma West ican Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31, 639-642. (Original work

Lecture at rhe Ninrh Occupational Science Symposium at rhe Uni- published 1922)

versiry of Southern California on April 12, 1996. It is respectfully Porn, 1. (1993). Health and adaptedness. Theoretical Medicine,

dedicated to rhe memory of Wilma West, MA, OTR. FAOTA, who con- 14.295-303.

tributed so much of her spirit to occupational rherapy. Reilly, M. (1962). Occupational rherapy can be one of rhe great

ideas of 20th century medicine, 1961 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture.

References American Journal ofOccupational Therapy, 16, 1-9.

Argyle. A. (1972). The social psychology ofwork, New York: Lap- Reilly, M. (1969). The educational process. American Journal of

linger. Occupational Therapy, 23. 299-307.

Argyle, M. (1987). The psychology ofhappiness, London: Merh- Reilly, M. (1974). Playas exploratory learning. Beverly Hills, CA:

ven.

Sage.

Beisser, A. (1989). Flying without wings: Personal reflectiom on

Rifkin, J. (1995). The end ofwork. New York: Putnam.

being disabled New York: Doubleday.

Storr, A. (1988). Solitude. A return to the self New York: Ballan-

Bernspang, B. (1987). Consequences ofstroke. Aspects ofimpair-

tine.

ments disabilities and lift satisfaction with special emphasis on perception

and occupational therapy, Unpublished medical dissertation, Umea Vash, C. L. (1981). The psychology ofdisability. Springerseries on

Universiry, Umea, Sweden. rehabilitation, 1. New York: Springer.

Bickenbach, J. (1993). Physical disability and social policy. T oron- Wright, B. (1983). Physical disability: A psychosocial approach

to, Ontario: Universiry of Toronto Press. (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond boredom and anxiety: The Ywca, E. J., & Baum, S. (1986). Engagement in daily occupa-

experience ofplay in work andgames. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. tions and life satisfaction among people with spinal cord injuries.

Dewey,]. (1910). How we think. Lexington, MA: Hearh. Occupational Therapy Journal ofResearch. 6, 271-283.

418 June 1998, Volume 52, Number 6

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 11/29/2018 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Human Spirit for Occupation and HealthDokument7 SeitenThe Human Spirit for Occupation and HealthShant KhatchikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frank Et Al 2010 Chronic Conditions Well-Being and Health in Global Contexts in Manderson and Smith-MorrisDokument17 SeitenFrank Et Al 2010 Chronic Conditions Well-Being and Health in Global Contexts in Manderson and Smith-MorrisS. LeighNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilcock 1998Dokument9 SeitenWilcock 1998Joaquin OlivaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2 PDFDokument24 SeitenModule 2 PDFElla Nika FangonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theories Focus on Holistic HealthDokument6 SeitenNursing Theories Focus on Holistic HealthBuklatin Lyra Elghielyn H.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wilcock 1998Dokument6 SeitenWilcock 1998Joaquin OlivaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- T1 Yerxa Ocupación Curriculum Centrado en La OcupaciónDokument8 SeitenT1 Yerxa Ocupación Curriculum Centrado en La OcupaciónDulceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theories in 40 CharactersDokument5 SeitenNursing Theories in 40 CharactersJam BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursin Philosophy and H PM T F Eptua Nur G: G T e en o Conc L Framework in SinDokument10 SeitenNursin Philosophy and H PM T F Eptua Nur G: G T e en o Conc L Framework in SinC. R. PintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theorist Person Health Nursing Environment Lydia Hall: "Three Aspects of Nursing: Care, Cure, Core."Dokument2 SeitenTheorist Person Health Nursing Environment Lydia Hall: "Three Aspects of Nursing: Care, Cure, Core."LYZZYTH ASENCINoch keine Bewertungen

- Concepts of Health, Wellness, and Well-BeingDokument15 SeitenConcepts of Health, Wellness, and Well-BeingEarl BenedictNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reorganizational Healing A Paradigm For The Advancement of Wellness, Behavior Change, Holistic Practice, and Healing Donald M. EpsteinDokument15 SeitenReorganizational Healing A Paradigm For The Advancement of Wellness, Behavior Change, Holistic Practice, and Healing Donald M. EpsteinVas RaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Activity MidtermDokument7 SeitenActivity Midtermreese's peanut butter cupsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Policy: The Role of Occupational Therapy in The Management of DepressionDokument6 SeitenHealth Policy: The Role of Occupational Therapy in The Management of DepressionMarina ENoch keine Bewertungen

- 14 - Fitzpatrick, Leininger, Rogers, Newman, Parse PDFDokument5 Seiten14 - Fitzpatrick, Leininger, Rogers, Newman, Parse PDFJuan Felipe Jaramillo SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chart of Nursing Theories and ModelsDokument3 SeitenChart of Nursing Theories and ModelsScribdTranslationsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Making Healthy Choices EasyDokument7 SeitenMaking Healthy Choices EasyscribalbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Classifying Nursing Theorists' Concepts of Nursing, Person, Health and EnvironmentDokument2 SeitenClassifying Nursing Theorists' Concepts of Nursing, Person, Health and EnvironmentBALDOZA LEO FRANCO B.Noch keine Bewertungen

- TFN MidtermsDokument12 SeitenTFN MidtermsChang Pearl Marjorie P.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of Man Health and IllnessDokument3 SeitenConcept of Man Health and IllnessChristian Shane BejeranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- MENTAL HEALTHDokument3 SeitenMENTAL HEALTHJudee EllosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Divino, Elizz Joy F.Dokument7 SeitenDivino, Elizz Joy F.reese's peanut butter cupsNoch keine Bewertungen

- College of Nursing Health, Wellness and Wellbeing GuideDokument15 SeitenCollege of Nursing Health, Wellness and Wellbeing GuideJoshua Dumanjug SyNoch keine Bewertungen

- N1R01A - Transes in Introduction To NursingDokument8 SeitenN1R01A - Transes in Introduction To NursingMikhaella GwenckyNoch keine Bewertungen

- N1R01A - Transes in Introduction To NursingDokument8 SeitenN1R01A - Transes in Introduction To NursingMikhaella GwenckyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systems TheoriesDokument35 SeitenSystems TheoriesJames Kurt CruzatNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Disability Paradox: High Quality of Life Against All OddsDokument12 SeitenThe Disability Paradox: High Quality of Life Against All OddsClaudia agamez insignaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reorganizational Healing: A Paradigm For The Advancement of Wellness, Behavior Change, Holistic Practice, and HealingDokument15 SeitenReorganizational Healing: A Paradigm For The Advancement of Wellness, Behavior Change, Holistic Practice, and HealingGabriel da RochaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aus Occup Therapy J - 2002 - Wilcock - Reflections On Doing Being and BecomingDokument11 SeitenAus Occup Therapy J - 2002 - Wilcock - Reflections On Doing Being and BecomingMelissa CroukampNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theorists and Their Theories Compilation ReviewerDokument5 SeitenNursing Theorists and Their Theories Compilation ReviewerJoshua Gabriel AntiqueraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PRDokument11 SeitenWilcock-Reflections On Doing, Being and Becoming - PRIsabel PereiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- DIVINO, Elizz Joy F. Activity MidtermDokument11 SeitenDIVINO, Elizz Joy F. Activity Midtermreese's peanut butter cupsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assingment M6 LA 1Dokument5 SeitenAssingment M6 LA 1rahmad khomeni84Noch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 113 - Lec Reviewer PrelimDokument9 SeitenNCM 113 - Lec Reviewer PrelimKylle AlimosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MetaparadigmsDokument2 SeitenMetaparadigmsRed DinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Occupation and Health Are They One and The SameDokument7 SeitenOccupation and Health Are They One and The SameJoaquin OlivaresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Theories and DefinitionDokument3 SeitenNursing Theories and DefinitionSareno PJhēaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCMA (TFN) Assignment Oct-20-20Dokument5 SeitenNCMA (TFN) Assignment Oct-20-20MC DARLIN DIAZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using The Person Environment Occupational Performance Conceptual Model As An Analyzing Framework For Health LiteracyDokument10 SeitenUsing The Person Environment Occupational Performance Conceptual Model As An Analyzing Framework For Health LiteracyCláudioToméNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond The Absent Body-A Phenomenological Contribution To The Understanding of Body Awareness in Health and IllnessDokument10 SeitenBeyond The Absent Body-A Phenomenological Contribution To The Understanding of Body Awareness in Health and IllnessHazarSayarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agbunag ResearchDokument4 SeitenAgbunag Researchsamantha quinonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Otd PsychosocialDokument4 SeitenOtd PsychosocialIzzah PijayNoch keine Bewertungen

- OCH52 Module 1Dokument21 SeitenOCH52 Module 1ALCANTARA ALYANNANoch keine Bewertungen

- Funda Lec Handout 1Dokument7 SeitenFunda Lec Handout 1HNoch keine Bewertungen

- AUTHORS_ THEORIESDokument2 SeitenAUTHORS_ THEORIESCHALSEA DYANN JOIE GALZOTENoch keine Bewertungen

- The Developmental-Health Framework Within The McGill Model of NursingDokument15 SeitenThe Developmental-Health Framework Within The McGill Model of NursingFerdy LainsamputtyNoch keine Bewertungen

- DOLEZAL-LYONS. Health Related Shame, An Affective Determinant of HealthDokument7 SeitenDOLEZAL-LYONS. Health Related Shame, An Affective Determinant of HealthNina NavajasNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCM 113 Lec TransesDokument8 SeitenNCM 113 Lec TransesKrystal MericulloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henderson PDFDokument11 SeitenHenderson PDFNicole SilorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health: Concept of Health & WellnessDokument5 SeitenHealth: Concept of Health & WellnessEm VibarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ryff, C. D. (2014) - Psychological Well-Being Revisited Advances in The Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Springer Publishing Company.Dokument31 SeitenRyff, C. D. (2014) - Psychological Well-Being Revisited Advances in The Science and Practice of Eudaimonia. Springer Publishing Company.nnovi6883Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Concept of Health and Illness PDFDokument6 SeitenThe Concept of Health and Illness PDFKaranja GitauNoch keine Bewertungen

- O Conceito de Saúde e A Diferença Entre Promoção e PrevençãoDokument9 SeitenO Conceito de Saúde e A Diferença Entre Promoção e PrevençãoBreno CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Useful Life Lessons For Health and Well Being Adults Reflections of Childhood Experiences Illuminate The Phenomenon of The Inner ChildDokument10 SeitenUseful Life Lessons For Health and Well Being Adults Reflections of Childhood Experiences Illuminate The Phenomenon of The Inner ChildluamsmarinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals in Nursing Lesson #1 INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTSDokument6 SeitenFundamentals in Nursing Lesson #1 INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTSSophia Duquinlay100% (1)

- Historical and Philosophical Perspectives of Occupational Therapy's Role in Health PromotionDokument21 SeitenHistorical and Philosophical Perspectives of Occupational Therapy's Role in Health PromotionLycan AsaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joy Marie LDokument5 SeitenJoy Marie LCharesse Angel SaberonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concept of food, nutrition and healthDokument6 SeitenConcept of food, nutrition and healthprajjwalbhattarai1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chemistry: Crash Course For JEE Main 2020Dokument17 SeitenChemistry: Crash Course For JEE Main 2020QSQFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Process Strategy PPT at BEC DOMSDokument68 SeitenProcess Strategy PPT at BEC DOMSBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)100% (1)

- ETEEAP Application SummaryDokument9 SeitenETEEAP Application SummaryAlfred Ronuel AquinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2022 MSK Poster JonDokument1 Seite2022 MSK Poster Jonjonathan wijayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Follow The Directions - GR 1 - 3 PDFDokument80 SeitenFollow The Directions - GR 1 - 3 PDFUmmiIndia100% (2)

- ADV7513 Hardware User GuideDokument46 SeitenADV7513 Hardware User Guide9183290782100% (1)

- General Format Feasibility StudyDokument7 SeitenGeneral Format Feasibility StudyRynjeff Lui-Pio100% (1)

- Public Dealing With UrduDokument5 SeitenPublic Dealing With UrduTariq Ghayyur86% (7)

- Paper 2Dokument17 SeitenPaper 2Khushil100% (1)

- Chapter 2 Planning Business MessagesDokument15 SeitenChapter 2 Planning Business MessagesNuriAisyahHikmahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safety Steering System Alarm Code GuideDokument43 SeitenSafety Steering System Alarm Code GuideIsrael Michaud84% (19)

- Automatic Helmet DetectDokument4 SeitenAutomatic Helmet Detectvasanth100% (1)

- Vocabulary Extension Starter Without AnswersDokument1 SeiteVocabulary Extension Starter Without AnswersPatrcia CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mental Health Stigma and Help SeekingDokument4 SeitenMental Health Stigma and Help SeekingJane Arian BerzabalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quiz 2 ReviewDokument17 SeitenQuiz 2 ReviewabubakkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presostatos KPI 1Dokument10 SeitenPresostatos KPI 1Gamaliel QuiñonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- i-PROTECTOR SPPR Catalogue 1.0Dokument2 Seiteni-PROTECTOR SPPR Catalogue 1.0Sureddi KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mohit Chakrabarti - Value Education - Changing PerspectivesDokument79 SeitenMohit Chakrabarti - Value Education - Changing PerspectivesDsakthyvikky100% (1)

- Managing Change Leading TransitionsDokument42 SeitenManaging Change Leading TransitionsSecrets26Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nordson EFD Ultimus I II Operating ManualDokument32 SeitenNordson EFD Ultimus I II Operating ManualFernando KrauchukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Karnaugh MapsDokument7 SeitenKarnaugh Mapsdigitales100% (1)

- Secondary SourcesDokument4 SeitenSecondary SourcesKevin NgoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Structure and ProfilesDokument178 SeitenOrganizational Structure and ProfilesImran Khan NiaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gabriel Feltran. "The Revolution We Are Living"Dokument9 SeitenGabriel Feltran. "The Revolution We Are Living"Marcos Magalhães Rosa100% (1)

- Mobile Phone Addiction 12 CDokument9 SeitenMobile Phone Addiction 12 Cvedang agarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 3 Unit 3 (English)Dokument1 SeiteGrade 3 Unit 3 (English)Basma KhedrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electrical Design Analysis: 3 Storey Commercial BuildingDokument6 SeitenElectrical Design Analysis: 3 Storey Commercial Buildingcjay ganir0% (1)

- PCH (R-407C) SeriesDokument53 SeitenPCH (R-407C) SeriesAyman MufarehNoch keine Bewertungen

- 26th IEEEP All Pakistan Students' SeminarDokument3 Seiten26th IEEEP All Pakistan Students' Seminarpakipower89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Army Aviation Digest - Feb 1967Dokument68 SeitenArmy Aviation Digest - Feb 1967Aviation/Space History LibraryNoch keine Bewertungen