Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The History of Plague - Part 1. The Three Great Pandemics

Hochgeladen von

NISAR_786Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The History of Plague - Part 1. The Three Great Pandemics

Hochgeladen von

NISAR_786Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

History

The History of Plague – Part 1.

The Three Great Pandemics

John Frith

Plague is an acute infectious disease caused by Pastorien and a French naval doctor, demonstrated

the bacillus Yersinia pestis and is still endemic in that the Oriental rat flea was the vector for the

indigenous rodent populations of South and North bacillus and the sources of the bacillus were the

America, Africa and Central Asia. In epidemics sewer rats.3,4

plague is transmitted to humans by the bite of the

Oriental or Indian rat flea and the human flea. The The germ, the rats, and the fleas

primary hosts of the fleas are the black urban rat and Yersinia pestis is most likely a clone that evolved

the brown sewer rat. Plague is also transmissible some 1,500 to 20,000 years ago from a common

person to person when in its pneumonic form. ancestor with Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, an animal

Yersinia pestis is a very pathogenic organism to both enteropathogen which does not cause blood infection

humans and animals and before antibiotics had a or plague. The bacillus probably arose in Asia,

very high mortality rate. Bubonic plague also has although it had been present in east-central Africa for

military significance and is listed by the Centers the past two millennia and probably longer.2, 5 There

for Disease Control and Prevention as a Category A are three biovars of the bacillus based on phenotypic

bioterrorism agent.1 differences, Antiqua, Medievalis, and Orientalis, and

There have been three great world pandemics of it has been postulated that they were responsible for

plague recorded, in 541, 1347, and 1894 CE, each the first, second and third pandemics respectively.

time causing devastating mortality of people and A paleomicrobiological analysis by Drancourt et al

animals across nations and continents. On more in 2004 however indicated that all three pandemics

than one occasion plague irrevocably changed the were most likely caused by the Orientalis biovar.6, 7

social and economic fabric of society. There had also been debate for some time whether the

In most human plague epidemics, infection initially Justinian and the Black Death plagues were actually

took the form of large purulent abscesses of lymph due to Yersinia pestis and were not instead epidemic

nodes, the bubo (L. bubo = ‘groin’, Gr. boubon = haemorrhagic fevers3,8. Analyses by Drancourt and

‘swelling in the groin’), this was bubonic plague. When others have found evidence of the plague bacillus

bacteraemia followed, it caused haemorrhaging and in specimens of persons known to have died in

necrosis of the skin rapidly followed by septicaemic the first two pandemics. It is also very difficult to

shock and death, septicaemic plague. If the disease discount the vivid and accurate descriptions of the

spread to the lung through the blood, it caused an bubonic plague that were given by historians such

invariably fatal pneumonia, pneumonic plague, and as Procopius of Caesarea, Gabriel de Mussis and

in that form plague was directly transmissible from Giovanni Boccaccio.

person to person. The vector host in the Black Death pandemic was

The three great plague pandemics had different Rattus rattus - the ‘old English’ or black rat. The

geographic origins and paths of spread. The Justinian black rat originated in India and migrated along

Plague of 541 started in central Africa and spread to the Silk Road from Asia to the Middle East, and

Egypt and the Mediterranean. The Black Death of then travelled in ships on the sea trade routes,

1347 originated in Asia and spread to the Crimea settling in most areas of the world and cohabitating

then Europe and Russia. The third pandemic, that comfortably with humans in their houses, factories,

of 1894, originated in Yunnan, China, and spread to and dockyards. The black rat had probably acquired

Hong Kong and India, then to the rest of the world.2 the disease from contact with infected wild rodents

from the steppes of Central Asia and Russia, and

The causative organism, Yersinia pestis, was not

in fact the disease may have been transported in

discovered until the 1894 pandemic and was

infested marmot hides taken by Tartar hunters

discovered in Hong Kong by a French Pastorien

from Manchuria. The brown or sewer rat, Rattus

bacteriologist, Alexandre Yersin. Four years later

norvegicus, didn’t become prevalent in the Western

in 1898 his successor, Paul-Louis Simond, a fellow

world until the 18th century. It originated in Central

Volume 20 Number 2; April 2012 Page 11

History

Asia and migrated westward on the sea routes from regard to what they were doing. And

China and India. The brown rat flourished in Europe the body showed no change from its

where there were open sewers and ample breeding previous colour, nor was it hot as

grounds and food and in the 18th and 19th centuries might be expected when attacked by a

replaced the black rat as the main disease host.4, 9 fever, nor indeed did any inflammation

set in, but the fever was of such a

The primary vectors for transmission of the disease

languid sort from its commencement

from rats to humans were the Oriental or Indian

and up till evening that neither to the

rat flea, Xenopsylla cheopis, and the Northern

sick themselves nor to a physician

or European rat flea, Nosopsyllus fasciatus. The

who touched them would it afford any

human flea, Pulex irritans, and the dog and cat fleas,

suspicion of danger. It was natural,

Ctenocephalides canis and felis, were secondary

therefore, that not one of those who had

vectors. In the pandemics, the infected fleas were

contracted the disease expected to die

able to spread the plague over long distances as

from it. But on the same day in some

they were carried by rats and by humans travelling

cases, in others on the following day,

along trade routes at sea and overland, and also by

and in the rest not many days later, a

infesting rice and wheat grain, clothing, and trade

bubonic swelling developed; and this

merchandise. When infected, the proventriculus

took place not only in the particular

of the flea becomes blocked by a mass of bacteria.

part of the body which is called boubon,

The flea continues to feed, biting with increasing

that is, “below the abdomen,” but also

frequency and agitation, and in an attempt to relieve

inside the armpit, and in some cases

the obstruction the flea regurgitates the accumulated

also beside the ears, and at different

blood together with a mass of Yersinia pestis bacilli

points on the thighs.”14

directly into the bloodstream of the host. The fleas

multiply prolifically on their host and when the host The focus of the Justinian pandemic was

dies they leave immediately, infesting new hosts and Constantinople, reaching a peak in the spring of 542

thus creating the foundations for an epidemic.10, 11 with 5,000 deaths per day in the city, although some

estimates vary to 10,000 per day, and it went on

The Justinian Plague of 541-544 to kill over a third of the city’s population. Victims

The first great pandemic of bubonic plague were too numerous to be buried and were stacked

where people were recorded as suffering from the high in the city’s churches and city wall towers,

characteristic buboes and septicaemia was the their Christian doctrine preventing their disposal by

Justinian Plague of 541 CE, named after Justinian cremation. Over the next three years plague raged

I, the Roman emperor of the Byzantine Empire at through Italy, southern France, the Rhine valley and

the time. The epidemic originated in Ethiopia in Iberia. The disease spread as far north as Denmark

Africa and spread to Pelusium in Egypt in 540. It and west to Ireland, then further to Africa, the

then spread west to Alexandria and east to Gaza, Middle East and Asia Minor. Between the years 542

Jerusalem and Antioch, then was carried on ships and 546 epidemics in Asia, Africa and Europe killed

on the sea trading routes to both sides of the nearly 100 million people.15, 16

Mediterranean, arriving in Constantinople (now The pandemic had a drastic effect and permanently

Istanbul) in the autumn of 541.12, 13 changed the social fabric of the Western world. It

The Byzantine court historian, Procopius of contributed to the demise of Justinian’s reign. Food

Caesarea, in his work History of the Wars, described production was severely disrupted and an eight year

people with fever, delirium and buboes He wrote that famine followed. The agrarian system of the empire

the epidemic was one ‘by which the whole human was restructured to eventually become the three field

race came near to be annihilated’. Procopius wrote feudal system. The social and economic disruption

of the symptoms of the disease : caused by the pandemic marked the end of Roman

rule and led to the birth of culturally distinctive

“ ... with the majority it came about societal groups that later formed the nations of

that they were seized by the disease medieval Europe.12

without becoming aware of what was

coming either through a waking vision Further major outbreaks occurred throughout

or a dream. ... They had a sudden fever, Europe and the Middle East over the next 200

some when just roused from sleep, years - in Constantinople in the years 573, 600, 698

others while walking about, and others and 747, in Iraq, Egypt and Syria in the years 669,

while otherwise engaged, without any 683, 698, 713, 732 and 750 and Mesopotamia in

686 and 704. In 664 plague laid waste to Ireland,

Page 12 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health

History

and in England it came to be known as the Plague ensued from the septicaemia. Ziegler17 states it

of Cadwaladyr’s Time, after a Welsh king who derives from the translation of the Latin pestis atra

contracted plague but survived it in 682. The plague or atra mors, ‘atra’ meaning ‘terrible’ or ‘dreadful’,

continued in intermittent cycles in Europe into the the connotation of which was ‘black’, and ‘mors’

mid-8th century and did not re-emerge as a major meaning ‘death’, and so ‘atra mors’ was translated

epidemic until the 14th century. as meaning ‘black death’.

The ‘Black Death’ of Europe in 1347 to 1352 The social impacts of the Black Death in Europe

The Black Death of 1347 was the first major European during the 14th century

outbreak of the second great plague pandemic that The overall mortality rate varied from city to city, but

occurred over the 14th to 18th centuries. In 1346 it in places such as Florence as observed by Boccaccio

was known in the European seaports that a plague up to half the population died, the Italians calling the

epidemic was present in the East. In 1347 the plague epidemic the mortalega grande, ‘the great mortality’.

was brought to the Crimea from Asia Minor by the [18]

People died with such rapidity that proper burial

Tartar armies of Khan Janibeg, who had laid siege or cremation could not occur, corpses were thrown

to the town of Kaffa (now Feodosya in Ukraine), a into large pits and putrefying bodies lay in their

Genoese trading town on the shores of the Black Sea. homes and in the streets. People were as much

The siege of the Tartars was unsuccessful and before afraid they would suffer a spiritual death as they

they left, from a description by Gabriel de Mussis were a physical death since there were no clergy to

from Piacenza, in revenge they catapulted over the perform burial rites:

walls of Kaffa corpses of people who had died from

the Black Death. In panic the Genoese traders fled “Shrift there was none; churches and

in galleys with ‘sickness clinging to their bones’ to chapels were open, but neither priest

Constantinople and across the Mediterranean to nor penitents entered – all went to

Messina, Sicily, where the great pandemic of Europe the charnelhouse. The sexton and

started. By 1348 it had reached Marseille, Paris and the physician were cast into the same

Germany, then Spain, England and Norway in 1349, deep and wide grave; the testator and

and eastern Europe in 1350. The Tartars left Kaffa his heirs and executors were hurled

and carried the plague away with them spreading it from the same cart into the same hole

further to Russia and India.17 together.”18

A description of symptoms of the plague was given by Transmission of the disease was thought to be by

Giovanni Boccaccio in 1348 in his book Decameron, miasmas, disease carrying vapours emanating from

a set of tales of a group of Florentines who secluded corpses and putrescent matter or from the breath of

themselves in the country to escape the plague : an infected or sick person. Others thought the Black

Death was punishment from God for their sins and

“.. in men and women alike it first immoral behaviour, or was due to astrological and

betrayed itself by the emergence of natural phenomena such as earthquakes, comets,

certain tumours in the groin or armpits. and conjunctions of the planets. People turned to

Some of which grew as large as a patron saints such as St Roch and St Sebastian or to

common apple, others as an egg, some the Virgin Mary, or joined processions of flagellants

more, some less, which the common folk whipping themselves with nail embedded scourges

called gavocciolo. From the two said and incanting hymns and prayers as they passed

parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo from town to town.17, 19, 20

soon began to propagate and spread

itself in all directions indifferently; after “When the flagellants – they were

which the form of the malady began also called cross brethren and cross

to change, black spots or livid making bearers – entered a town, a borough or

their appearance in many cases on the a village in a procession their entry was

arm or the thigh or elsewhere,..“17 accompanied by the pealing of bells,

singing, and a huge crowd of people. As

The term “Black Death” was not used until much they always marched two abreast, the

later in history and in 1347 was simply known as procession of the numerous penitents

“the pestilence” or “pestilentia”, and there are various reached farther than the eye could see.”

explanations of the origin of the term. Butler [11] [20]

states the term refers to the haemorrhagic purpura

and ischaemic gangrene of the limbs that sometimes The only remedies were inhalation of aromatic

vapours from flowers and herbs such as rose,

Volume 20 Number 2; April 2012 Page 13

History

theriaca, aloe, thyme and camphor. Soon there was the period for which Christ fasted in the desert, or

a shortage of doctors which led to a proliferation of the ancient Greek doctrine of “critical days” which

quacks selling useless cures and amulets and other held that contagious disease will develop within 40

adornments that claimed to offer magical protection. days after exposure.22 In the 14th and 15th centuries

following, most countries in Europe had established

In this second pandemic, plague again caused great

quarantine, and in the 18th century Habsburg

social and economic upheaval. Often whole families

established a cordon sanitaire, a line between

were wiped out and villages abandoned. Crops

infected and clean parts of the continent which ran

could not be harvested, travelling and trade became

from the Danube to the Balkans. It was manned

curtailed, and food and manufactured goods became

by local peasants with checkpoints and quarantine

short. As there was a shortage of labour, surviving

stations to prevent infected people from crossing

villager labourers, the ‘villeins’, extorted exorbitant

from eastern to western Europe.8

wages from the remaining aristocratic landowners.

The villeins prospered and acquired land and

property. The plague broke down the normal divisions The leather costume of the plague doctors at

between the upper and lower classes and led to the Nijmegen

emergence of a new middle class.17, 9 The plague In the 15th and 16th centuries doctors wore a

lead to a preoccupation with death as evident from peculiar costume to protect themselves from the

macabre artworks such as the ‘Triumph of Death’ by plague when they attended infected patients, first

Pieter Breughel the Elder in 1562, which depicted in illustrated in a drawing by Paulus Furst in 1656

a panoramic landscape armies of skeletons killing and later Jean-Jacques described a similar costume

people of all social orders from peasants to kings and worn by the plague doctors at Nijmegen, an old

cardinals in a variety of macabre and cruel ways. Dutch town in Gelderland, in his 1721 work Treatise

on the Plague. They wore a protective garb head to

In the period 1347 to 1350 the Black Death killed a

foot with leather or oil cloth robes, leggings, gloves

quarter of the population in Europe, over 25 million

and hood, a wide brimmed hat which denoted their

people, and another 25 million in Asia and Africa.[15]

medical profession, and a beak like mask with glass

Mortality was even higher in cities such as Florence,

eyes and two breathing nostrils which was filled with

Venice and Paris where more than half succumbed

aromatic herbs and flowers to ward off the miasmas.

to the plague. A second major epidemic occurred

They avoided contact with patients by taking their

in 1361, the pestis secunda, in which 10 to 20% of

pulse with a stick or issued prescriptions for aromatic

Europe’s population died.13 Other virulent infectious

herb inhalations passing them through the door, and

disease epidemics with high mortalities occurred

buboes were lanced with knives several feet long.19

during this time such as smallpox, infantile diarrhoea

and dysentery. By 1430, Europe’s population was

lower than it had been in 1290 and would not recover The Great Plague of London of 1665 to 1666

the pre-pandemic level until the 16th century.13, 21 Plague continued to occur in small epidemics

throughout the world but a major outbreak of the

Quarantine pneumonic plague occurred in Europe and England

in 1665 to 1666. The epidemic was described by

In 1374 when another epidemic of the Black Death

Samuel Pepys in his diaries in 1665 and by Daniel

re-emerged in Europe, Venice instituted various

Defoe in 1722 in his A Journal of a Plague Year.

public health controls such as isolating victims from

People were incarcerated in their homes, doors

healthy people and preventing ships with disease

painted with a cross. The epidemic reached a peak

from landing at port. In 1377 the republic of Ragusa

in September 1665 when 7,000 people per week were

on the Adriatic Sea (now Dubrovnik in Yugoslavia)

dying in London alone. Between 1665 and 1666 a

established a ships’ landing station far from the city

fifth of London’s population died, some 100,000

and harbour in which travellers suspected to have

people.[17] The Great Fire of London in 1666 and the

the plague had to spend thirty days, the trentena, to

subsequent rebuilding of timber and thatch houses

see whether they became ill and died or whether they

with brick and tile disturbed the rats’ normal habitat

remained healthy and could leave. The trentena was

and led to a reduction in their numbers, and may

found to be too short and in 1403 in Venice, travellers

have been a contributing factor to the end of the

from the Levant in the eastern Mediterranean were

epidemic.9

isolated in a hospital for forty days, the quarantena

or quaranta giorni, from which we derive the term An old English nursery rhyme published in Kate

quarantine.8,18 This change to forty days may have Greenaway’s book Mother Goose 1881 reminds us of

also been related to other biblical and historical the symptoms of the plague :

references such as the Christian observance of Lent,

Page 14 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health

History

‘Ring, a-ring, o’rosies, (a red blistery rash) and their fleas were the vectors in the epidemic.

There were 12 major outbreaks of plague in Australia

A pocket full of posies (fragrant herbs

from 1900 to 1925 with 1371 cases and 535 deaths,

and flowers to ward off the ‘miasmas’)

most cases occurring in Sydney.26

Atishoo, atishoo (the sneeze and the

The third pandemic waxed and waned throughout

cough heralding pneumonia)

the world for the next five decades and did not end

We all fall down.’ (all dead) until 1959, in that time plague had caused over 15

million deaths, the majority of which were in India.

Plague waxed and waned in Europe until the late 18th

There have been outbreaks of plague since, such as

century, but not with the virulence and mortality of

in China and Tanzania in 1983, Zaire in 1992, and

the 14th century European Black Death.

India, Mozambique and Zimbabwe in 199415, 27. In

Madagascar in the mid-1990’s, a multi-drug resistant

The Third Pandemic of 1894

strain of the bacillus was identified15, 28. Currently

The plague re-emerged from its wild rodent reservoir around 2,000 cases occur annually, mostly in Africa,

in the remote Chinese province of Yunnan in 1855. Asia and South America, with a global case fatality

From there the disease advanced along the tin and rate of 5% to 15%.28

opium routes and reached the provincial capital of

K’unming in 1866, the Gulf of Tonkin in 1867, and Bubonic plague is a virulent disease with a significant

the Kwangtung province port of Pakhoi (now Pei- mortality rate, transmitted primarily by the bite of

hai) in 1882. In 1894 it had reached Canton and the rat flea or through person-to-person when in

then spread to Hong Kong. It had spread to Bombay its pneumonic form. There have been innumerable

by 1896 and by 1900 had reached ports on every epidemics of plague throughout history, but it was

continent, carried by infected rats travelling the the pandemics of the 6th, 14th and 20th centuries

international trade routes on the new steamships.3,23 that have had the most impact on human society,

It was in Hong Kong in 1894 that Alexandre Yersin not only in terms of the great mortalities, but also

discovered the bacillus now known as Yersinia pestis, the social, economic and cultural consequences that

and in Karachi in 1898 that Paul-Louis Simond resulted. The course of development of communities

discovered the brown rat was the primary host and and nations was altered several times. Much has

the rat flea the vector of the disease.3, 4, 24, 25 changed to prevent the recurrence of pandemic

plague, such as the development of the germ theory

In 1900 the plague came to Australia where the first and the science of bacteriology, public health

major outbreak occurred in Sydney, its epicentre at measures such as quarantine, and antibiotics

the Darling Harbour wharves, spreading to the city, such as streptomycin, but plague today is still an

Surry Hills, Glebe, Leichhardt, Redfern, and The important and potentially serious threat to the

Rocks, and causing 100 deaths. John Ashburton- health of people and animals.

Thompson, the chief medical officer, recorded the

epidemic and confirmed that rats were the source Author’s Affiliation: Australian Defence Force

Contact author: John Frith

Email: jfrith@unwired.com.au

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Emergency Preparedness and Response: Bioterrorism –

Agents/Diseases. Available at : http://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/agentlist-category.asp, accessed on

6.11.11.

2. Achtman M, Zurth K, Morelli G, Torrea G, Guiyoule A, Carniel E. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague,

is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 1999; 96 (24): 14043-

14048. Available at : http://www.pnas.org/content/96/24/14043.full.pdf , accessed on 3.11.11.

3. Echenberg M. Plague Ports. New York; New York University Press, 2007.

4. Marriott E. Plague. New York: Metropolitan Books - Henry Holt & Co, 2003.

5. Gage KL, Kosoy MY. Natural history of plague: perspectives from more than a century of research. Ann

Rev Entomol 2005; 50: 505-528. Available at : http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.

ento.50.071803.130337?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed ,

accessed on 15.11.11.

Volume 20 Number 2; April 2012 Page 15

History

6. Drancourt M, Roux V, Dang LV, Tran-Hung L, Castex D, Chenal-Francisque V, Ogata H, Fournier P-E,

Crubezy E, Raoult D. Genotyping Orientalis-like Yersinia pestis, and plague pandemics. Emerging Inf Dis

2004; 10 (9): 1585-1592. Available at : http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/10/9/03-0933_article.htm ,

accessed on 3.11.11

7. Raoult D, Drancourt M. Yersinia Pestis and Plague. University of Marseille. 2006. Available at :

http://ifr48.timone.univ-mrs.fr/Fiches/Yersinia_pestis_Plague.html, accessed on 3.11.11.

8. Dobson M. Disease: The Extraordinary Stories Behind History’s Deadliest Killers. Quercus: London, 2007.

9. Porter S. The Great Plague. Phoenix Mill, Gloucestershire; Sutton Publishing, 1999.

10 Gratz N. Rodent Reservoirs & Flea Vectors of Natural Foci of Plague. In : WHO. Plague Manual:

Epidemiology, Distribution, Surveillance and Control. 2011. WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/99.2. Available at :

http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/plague/whocdscsredc992b.pdf , accessed on 19.11.11.

11 Butler T. Plague and Other Yersinia Infections. New York: Plenum Medical Book Company, 1983.

12. Rosen W. Justinian’s Flea: The First Great Plague and the End of the Roman Empire. New York: Viking

Penguin, 2007.

13. Gottfried RS. The Black Death. London: Robert Hale Ltd, 1983.

14. Halsall P. Medieval Sourcebook: Procopius: The Plague, 542. 1998. Available at : http://www.fordham.

edu/halsall/source/542procopius-plague.asp , accessed on 19.11.11.

15. Tikhomirov E. Epidemiology and Distribution of Plague. In : WHO. Plague Manual: Epidemiology,

Distribution, Surveillance and Control. 2011. WHO/CDS/CSR/EDC/99.2. Available at :

http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/plague/whocdscsredc992a.pdf , accessed on 10.11.11.

16. Morony MG. “For Whom Does the Writer Write ?” The First Bubonic Plague Pandemic According to Syriac

Sources. In : Little LK. Plague and the End of Antiquity: The Pandemic of 541-750. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 2007.

17. Zeigler P. The Black Death. Godalming, Surrey: Bramley Books, 1969.

18. Garrison F H. An Introduction to the History of Medicine. Philadelphia & London: W B Saunders & Co.,

1921.

19. Schreiber W, Mathys FK. Infectio: Infectious Diseases in the History of Medicine. Basle: F. Hoffman – La

Roche & Co, 1987.

20. Nohl J. The Black Death: A Chronicle of the Plague. (Translated by CH Clarke). London: George Allen &

Unwin, 1926.

21. Damen M. History and Civilisation: Section 6: The Black Death. 2010. [On-line] Available at http://www.

usu.edu/markdamen/1320hist&civ/chapters/06plague.htm , accessed on 1.4.12.

22. Mackowiak PA, Sehdev PS. The origin of quarantine. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 35 (9): 1071-1072. Available

at : http://cid.oxfordjournals.org/content/35/9/1071.full, accessed on 17.11.11

23. Gregg CT. Plague: An Ancient Disease in the Twentieth Century. Revised edition. Albuquerque; University

of New Mexico Press, 1985.

24. Archives de l’ Institut Pasteur. Alexandre Yersin (1863-1943). Available at : http://www.pasteur.fr/

infosci/archives/e_yer0.html , accessed on 24.11.10.

25. Archives de l’ Institut Pasteur. Paul-Louis Simond (1858-1947). Available at : http://www.pasteur.fr/

infosci/archives/e_sim0.html , accessed on 27.10.11.

26. Curson PH. Times of Crisis: Epidemics in Sydney 1788-1900. Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1985.

27. Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis – etiologic agent of plague. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997; 10 (1): 35-

66. Available at : http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172914/pdf/100035.pdf , accessed on

2.4.12.

28. WHO. Zoonotic Infections – Plague. 2012. Available at : http://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/

zoonotic/en/index3.html , accessed on 2.4.12.

Page 16 Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 21ST Century IlluminatiDokument29 Seiten21ST Century IlluminatiNISAR_786100% (4)

- Lug Star Trek RPG Netbook - An Open Mind - Mindmelds and Empaths - The Psionics SourcebookDokument118 SeitenLug Star Trek RPG Netbook - An Open Mind - Mindmelds and Empaths - The Psionics SourcebookMax Hertzog100% (3)

- Natural MedicineDokument182 SeitenNatural MedicineNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Canadian Encyclopedia of Natural MedicineDokument455 SeitenCanadian Encyclopedia of Natural MedicineNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Using The Flea As A WeaponDokument6 SeitenUsing The Flea As A WeaponReid KirbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Synthesis: Repertorium Homoeopathicum SyntheticumDokument29 SeitenSynthesis: Repertorium Homoeopathicum SyntheticumSk Saklin Mustak67% (3)

- 10 Super Foods For Super JointsDokument38 Seiten10 Super Foods For Super JointsNISAR_786100% (1)

- 15 Natural Remedies For Heartburn & Severe Acid RefluxDokument60 Seiten15 Natural Remedies For Heartburn & Severe Acid RefluxNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Everyday Health Guide: 365 Tips For Healthy LivingDokument136 SeitenEveryday Health Guide: 365 Tips For Healthy LivingNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- 20 Pain Cures in Our Kitchen CupboardDokument24 Seiten20 Pain Cures in Our Kitchen CupboardNISAR_786100% (1)

- Peat PDFDokument44 SeitenPeat PDFMary June Hayrelle Sale100% (2)

- Justinian PlagueDokument2 SeitenJustinian PlagueLaura BessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Care Plan For Schizoaffective Disorder Bipolar TypeDokument4 SeitenCare Plan For Schizoaffective Disorder Bipolar TypeAlrick Asentista100% (2)

- 7 Deadliest Diseases in HistoryDokument9 Seiten7 Deadliest Diseases in HistoryRth CMglNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Politically Incorrect Guide to PandemicsVon EverandThe Politically Incorrect Guide to PandemicsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Smallpox The Triumph Over The Most Terrible of The Ministers of DeathDokument8 SeitenSmallpox The Triumph Over The Most Terrible of The Ministers of Deathnacxit6Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Black Death: Rosemary HorroxDokument353 SeitenThe Black Death: Rosemary Horroxshadydogv5100% (5)

- Alternative Medicine by Harriet HallDokument4 SeitenAlternative Medicine by Harriet HallNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plague!: Epidemics and Scourges Through the AgesVon EverandPlague!: Epidemics and Scourges Through the AgesBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (1)

- Plagues and Pandemics: Black Death, Coronaviruses and Other Deadly Diseases of the Past, Present and FutureVon EverandPlagues and Pandemics: Black Death, Coronaviruses and Other Deadly Diseases of the Past, Present and FutureBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Cystic Fibrosis Nursing Care PlanDokument15 SeitenCystic Fibrosis Nursing Care PlanAira Anne Tonee VillaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCP GastroenteritisDokument1 SeiteNCP GastroenteritisFranchesca PaunganNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 - ClinicalDokument11 Seiten4 - Clinicalapi-464332286100% (1)

- Ndebreleasedquestions 2019 1 PDFDokument383 SeitenNdebreleasedquestions 2019 1 PDFManish JunejaNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of The Plague: An Ancient Pandemic For The Age of COVID-19Dokument6 SeitenHistory of The Plague: An Ancient Pandemic For The Age of COVID-19Diego TulcanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plague: From Natural Disease To Bioterrorism: S R, MD, P DDokument9 SeitenPlague: From Natural Disease To Bioterrorism: S R, MD, P DJuan Carlos GutiérrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- INFOGRAPHIC CORRECTED Pandemic, Virus and Vaccines by PumarealesDokument4 SeitenINFOGRAPHIC CORRECTED Pandemic, Virus and Vaccines by Pumarealesel milanesasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chap 16 - History of Small PoxDokument12 SeitenChap 16 - History of Small PoxJean-Pierre GhnassiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History and Natural History of Dengue FeverDokument2 SeitenThe History and Natural History of Dengue Feverchiquilon749100% (1)

- C6-Lecture 4 On Black DeathDokument16 SeitenC6-Lecture 4 On Black Deathaparupawork22Noch keine Bewertungen

- Were Moses and Aaron The First Bioterrorists - Forensic ScienceDokument8 SeitenWere Moses and Aaron The First Bioterrorists - Forensic Sciencekutil.kurukshetraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black DeathDokument6 SeitenBlack Deathapi-308366238Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lerios Week14ct8Dokument1 SeiteLerios Week14ct8janine kylaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yellow FeverDokument9 SeitenYellow Feversag50942723Noch keine Bewertungen

- Black DeathDokument51 SeitenBlack DeathSiyamthanda GanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 of These Deadly Pandemics That Changed The WorldDokument8 Seiten10 of These Deadly Pandemics That Changed The WorldEdmar TabinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Postgrad Med J 2005 Duncan 315 20Dokument7 SeitenPostgrad Med J 2005 Duncan 315 20Rigoberto ZmNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Plague: 3. The Archaeology of The 2nd Plague Pandemic (1348-1722 CE) : An Overview of French Funerary ContextsDokument2 SeitenHistory of Plague: 3. The Archaeology of The 2nd Plague Pandemic (1348-1722 CE) : An Overview of French Funerary ContextsLâm NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Black DeathDokument6 SeitenThe Black DeathjaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black DeathDokument6 SeitenBlack Deathapi-237394422Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bio ProjectDokument19 SeitenBio ProjectPRIYA DARSHANNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Caused The Black Death?: History of MedicineDokument6 SeitenWhat Caused The Black Death?: History of MedicineKhiZra ShahZadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bubonic Plague EssayDokument2 SeitenBubonic Plague Essayapi-655303552Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Bubonic Plague, Spanish Flu and Covid 19Dokument16 SeitenThe Bubonic Plague, Spanish Flu and Covid 19maia harnauthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benedictow, The Black Death The Greatest Catastrophe EverDokument7 SeitenBenedictow, The Black Death The Greatest Catastrophe EverNagy BalazsNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Informative EssayDokument1 SeiteEnglish Informative EssayPaul Christian G. SegumpanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The PlagueDokument26 SeitenThe PlagueJina NjNoch keine Bewertungen

- World History of PandemicDokument8 SeitenWorld History of PandemicDrizzy MarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black DeathDokument5 SeitenBlack DeathClaudia CheveresanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Black PlagueDokument3 SeitenThe Black PlagueKevin MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- "There Is No Contagion, There Is No Evil Portent":: Arabic Responses To Plague and Contagion in The Fourteenth CenturyDokument52 Seiten"There Is No Contagion, There Is No Evil Portent":: Arabic Responses To Plague and Contagion in The Fourteenth CenturyimreadingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Degue Web ResearchDokument5 SeitenDegue Web ResearchdavefamilyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 of The Worst Pandemics in The HistoryDokument2 Seiten10 of The Worst Pandemics in The HistoryprincessyeshacNoch keine Bewertungen

- ClinMicrobiolInfect20 191 195 2014Dokument5 SeitenClinMicrobiolInfect20 191 195 2014yulia fitri00Noch keine Bewertungen

- Middle Age Europe's PandemicsDokument3 SeitenMiddle Age Europe's PandemicsJorge A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Discovering The Internet Brief 5th Edition Jennifer Campbell Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDokument22 SeitenDiscovering The Internet Brief 5th Edition Jennifer Campbell Test Bank Full Chapter PDFstrangstuprumczi100% (10)

- Project Muse 399418Dokument34 SeitenProject Muse 399418Décio GuzmánNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bubonic Plague in ChinaDokument14 SeitenBubonic Plague in ChinaКирилл ХолоденкоNoch keine Bewertungen

- Escaping Pandora's Box - Another Novel Coronavirus: PerspectiveDokument3 SeitenEscaping Pandora's Box - Another Novel Coronavirus: PerspectivefaisaladeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virus Del Papiloma2Dokument3 SeitenVirus Del Papiloma2JOSE EDUARDO PALACIOS HERNANDEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plague of JustinianDokument5 SeitenPlague of JustinianХристинаГулеваNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12Dokument48 Seiten12BenjaminFigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feature ArticleDokument2 SeitenFeature ArticleChantelle BlakeleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Black DeathDokument1 SeiteThe Black DeathNick LiuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leptospirosis Cap 142Dokument11 SeitenLeptospirosis Cap 142EdsonPerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plague 101 - National GeographicDokument3 SeitenPlague 101 - National GeographicTôi Đi HọcNoch keine Bewertungen

- UntitleddocumentDokument2 SeitenUntitleddocumentapi-319343807Noch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Black DeathDokument1 SeiteThe History of Black DeathAlbert Leon ManullangNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Download Discovering Psychology Eighth Edition Ebook PDF Version Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterDokument36 SeitenHow To Download Discovering Psychology Eighth Edition Ebook PDF Version Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterflorentina.tafolla694100% (28)

- Black Death ReadingDokument16 SeitenBlack Death Readingthejacobshow24553Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plau GueDokument4 SeitenPlau Gueslatson10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Black Death PaperDokument5 SeitenBlack Death PaperCody SpengelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Black Death Epidemic ThesisDokument21 SeitenBlack Death Epidemic ThesisHaina Angela AlibasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Middle Ages - Bubonic PlagueDokument4 SeitenThe History of Middle Ages - Bubonic PlagueMonsour SalazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epidemic, Pandemic, Should I Call the Medic? Biology Books for Kids | Children's Biology BooksVon EverandEpidemic, Pandemic, Should I Call the Medic? Biology Books for Kids | Children's Biology BooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Try at Home Make CompassDokument2 SeitenTry at Home Make CompassNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tradesmath PerW LADokument4 SeitenTradesmath PerW LANISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- All About A Compass - Finding My WayDokument3 SeitenAll About A Compass - Finding My WayNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Use A Compass!Dokument8 SeitenHow To Use A Compass!NISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Or CF Math Num e 01 CalcperDokument9 SeitenOr CF Math Num e 01 CalcperNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheet PercentagesDokument7 SeitenWorksheet PercentagesNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Asthma Pocket GuideDokument32 SeitenAsthma Pocket GuideNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kefir's HistoryDokument22 SeitenKefir's HistoryNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Claustrophobia (Fear of Enclosed Spaces) !Dokument5 SeitenWhat Is Claustrophobia (Fear of Enclosed Spaces) !NISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spread of Islam in West Africa: (English - ي�ﻠ�ﻧ)Dokument15 SeitenSpread of Islam in West Africa: (English - ي�ﻠ�ﻧ)NISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- This Brilliant $200 Hearing Aid Is Taking Canada by Storm: AdvertorialDokument26 SeitenThis Brilliant $200 Hearing Aid Is Taking Canada by Storm: AdvertorialNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hand Washing - Post TreatmentDokument23 SeitenHand Washing - Post TreatmentNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) - If You Think You're SickDokument3 SeitenCoronavirus (COVID-19) - If You Think You're SickNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cabin Fever Symptoms and Coping Skills PDFDokument4 SeitenCabin Fever Symptoms and Coping Skills PDFNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stoicism - All AboutDokument1 SeiteStoicism - All AboutNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Myth Busters - COVID-19Dokument21 SeitenMyth Busters - COVID-19NISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- Symptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaDokument4 SeitenSymptomatic-Asymptomatic - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediaNISAR_786Noch keine Bewertungen

- High Risk Pregnancy HB TranxDokument11 SeitenHigh Risk Pregnancy HB TranxangeliquepastranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ExcerptDokument2 SeitenExcerptcoloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bhagatwala Et Al 2015, Indications and ContraindicationsDokument27 SeitenBhagatwala Et Al 2015, Indications and Contraindicationsedo adimastaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Vegan PowerDokument3 SeitenA Vegan PowerashankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPPA SampleDokument28 SeitenIPPA Samplekimglaidyl bontuyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDokument9 SeitenHyperemesis Gravidarumkeith andriesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Minute Exam DFSDokument2 Seiten3 Minute Exam DFSWeeChuan NgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Formula Tepung Okkara Dan Tepung Beras Hitam PDFDokument7 SeitenFormula Tepung Okkara Dan Tepung Beras Hitam PDFSistha oklepeNoch keine Bewertungen

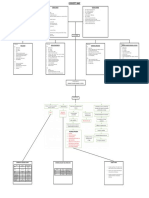

- IM-CAP Concept MapDokument1 SeiteIM-CAP Concept MapTrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indra Nooyi Draws On Vision and Values To LeadDokument1 SeiteIndra Nooyi Draws On Vision and Values To Leadimrul khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spinal Exercise Home ProgrammeDokument19 SeitenSpinal Exercise Home ProgrammePrabha VetrichelvanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-Disease MechanismsDokument5 Seiten1-Disease MechanismsMarian Dane PunzalanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orbit (Kankis)Dokument42 SeitenOrbit (Kankis)Jel JelitaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris (Health)Dokument17 SeitenTugas Bahasa Inggris (Health)Weni nuraeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sped in Mapeh FinalDokument30 SeitenSped in Mapeh FinalAngelle Bahin100% (2)

- Biers BlockDokument4 SeitenBiers Blockemkay1234Noch keine Bewertungen

- JKMJKDokument5 SeitenJKMJKSuci IrianiNoch keine Bewertungen

- In MemoriamDokument6 SeitenIn MemoriamChristopher PhillipsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bethel Schools 2018-2019 CalendarDokument1 SeiteBethel Schools 2018-2019 CalendarSinclair Broadcast Group - EugeneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuberculous MeningitisDokument8 SeitenTuberculous MeningitisEchizen RukawaNoch keine Bewertungen

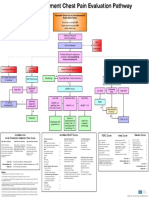

- Emergency Department Chest Pain Evaluation PathwayDokument2 SeitenEmergency Department Chest Pain Evaluation Pathwaymuhammad sajidNoch keine Bewertungen