Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Anticoagulantes en El Embarazo

Hochgeladen von

namizuOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Anticoagulantes en El Embarazo

Hochgeladen von

namizuCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review www. AJOG.

org

OBSTETRICS

Antithrombotic therapy and pregnancy: consensus report and

recommendations for prevention and treatment of venous

thromboembolism and adverse pregnancy outcomes

Adam J. Duhl, MD; Michael J. Paidas, MD; Serdar H. Ural, MD; Ware Branch, MD; Holly Casele, MD; Joan Cox-Gill, MD;

Sheri Lynn Hamersley, MD; Thomas M. Hyers, MD; Vern Katz, MD; Randall Kuhlmann, MD, PhD;

Edith A. Nutescu, PharmD; James A. Thorp, MD; James L. Zehnder, MD;

for the Pregnancy and Thrombosis Working Group

T he incidence of pregnancy-related

venous thromboembolism (VTE) is

difficult to measure. The common

Venous thromboembolism and adverse pregnancy outcomes are potential complica-

tions of pregnancy. Numerous studies have evaluated both the risk factors for and the

symptoms and signs are nonspecific— prevention and management of these outcomes in pregnant patients. This consensus

dyspnea, tachypnea, peripheral edema, group was convened to provide concise recommendations, based on the currently

and leg pain—and are often associated available literature, regarding the use of antithrombotic therapy in pregnant patients at

with advanced, normal pregnancy, risk for venous thromboembolic events and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

sometimes making the diagnosis diffi-

cult. Even when VTE is suspected, some Key words: pregnancy, thrombophilia, venous thromboembolism

practitioners are reluctant to use diag- Cite this article as: Duhl AJ, Paidas MJ, Ural SH, et al. Antithrombotic therapy and pregnancy:

nostic tests because of fears of radiation consensus report and recommendations for prevention and treatment of venous thromboembo-

exposure to the fetus. Consequently, the lism and adverse pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197:457.e1-457.e21.

occurrence of VTE is probably underes-

timated in pregnant patients. Despite

these difficulties, the incidence of VTE in leading cause of maternal death in both who experience DVT during pregnancy

pregnancy is reported to be 4- to 6-fold the United Kingdom and North Amer- are also more likely to have poor preg-

higher than in age-matched nonpreg- ica, with death from PE occurring in 2 in nancy outcomes. Furthermore, the risk

nant women,1,2 and pulmonary embo- 100,000 deliveries in the United King- of VTE extends to the postpartum pe-

lism (PE) remains a frequent cause of dom4 and representing 11% of maternal riod, with 50% of VTE cases occurring

maternal mortality.2,3 Indeed, VTE is the deaths in the United States.5 Women postpartum.6

After a firm diagnosis of VTE has been

From the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mercy Hospital of Pittsburgh, made in the pregnant patient, the per-

Pittsburgh, PA (Dr Duhl); the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Yale University ceived complications of antithrombotic

School of Medicine, New Haven, CT (Dr Paidas); the Department of Obstetrics and therapy sometimes delay or inhibit its im-

Gynecology, Penn State University, Hershey, PA (Dr Ural); the Department of Obstetrics plementation. A pregnant patient’s risk of

and Gynecology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT (Dr Branch); the Department of having VTE develop is difficult to estimate

Obstetrics and Gynecology, San Diego Perinatal Center, San Diego, CA (Dr Casele); the and is dependent on numerous factors,

Comprehensive Center for Bleeding Disorders, Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee,

some not readily identifiable by clinical

WI (Drs Cox-Gill and Kuhlmann); the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shady

Grove Adventist Hospital, Potomac, MD (Dr Hamersley); the Department of Pulmonary history or examination. As a result, identi-

Services, CARE Clinical Research, St Louis, MO (Dr Hyers); the Department of Obstetrics fying the patient who would benefit from

and Gynecology, Center for Genetic and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Eugene, OR (Dr Katz); prophylaxis is difficult. A number of pub-

the Antithrombosis Services, University of Illinois College of Pharmacy, Chicago, IL (Ms lications have addressed these problems,

Nutescu); the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sacred Heart Women’s Hospital, and some guidelines for prevention and

Pensacola, FL (Dr Thorp); and the Department of Hematology/Clinical Oncology, Stanford treatment of VTE have been issued.7-10

University Medical Center, Stanford, CA (Dr Zehnder). However, these guidelines are incomplete

Received Dec. 6, 2006; revised March 23, 2007; accepted April 1, 2007. and are not always evidence based. The

Reprints not available from the authors. major reason for this deficiency is the rela-

Funding for the meetings and editorial assistance for the manuscript were provided by Aventis tive paucity of well-designed, properly

Pharmaceuticals, a member of the Sanofi-Aventis group. The working group, however, powered, randomized controlled trials in

maintained full and independent responsibility for content of the consensus document.

prevention and treatment of thromboem-

0002-9378/$32.00

bolism associated with pregnancy.

© 2007 Mosby, Inc. All rights reserved.

doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.022 To define current consensus on these is-

sues an expert meeting was organized by

NOVEMBER 2007 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 457.e1

Review Obstetrics www.AJOG.org

TABLE 1

Grading of evidence according to the US Preventive Services Task Force11

Grade of evidence

I Evidence obtained from at least 1 properly designed randomized controlled trial.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

II-1 Evidence obtained from well-designed controlled trials without randomization.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

II-2 Evidence obtained from well-designed cohort or case-control analytic studies, preferably from more than one center

or research group.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

II-3 Evidence obtained from multiple time series with or without the intervention. Dramatic results in uncontrolled

experiments also could be regarded as this type of evidence.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

III Opinions of respected authorities, based on clinical experience, descriptive studies, or reports of expert committees.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Recommendation

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

A Recommendation is based on good and consistent scientific evidence.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

B Recommendation is based on limited or inconsistent scientific evidence.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

C Recommendation is based primarily on consensus and expert opinion.

Aventis Pharmaceuticals, a member of the P HARMACOLOGIC is minimally secreted into the breast milk

Sanofi-Aventis group. In subgroups, 6 top- M ANAGEMENT OF VTE IN and is therefore considered safe to use in

ics were discussed, including identification P REGNANCY breastfeeding mothers.7,16 Treatment

of the problem, risk assessment, options of Management of thrombosis in preg- guidelines recommend postpartum anti-

prevention and counseling for VTE, op- nancy remains a challenge. The antico- coagulation with warfarin for 4-6 weeks

tions of prevention and counseling for agulant drugs currently available for the with a target international normalized

poor obstetric history, practical manage- prevention and treatment of VTE in- ratio (INR) of 2.0-3.0 (with overlap with

ment of anticoagulation and pregnancy, clude warfarin, unfractionated heparin UFH or LMWH until the INR ⱖ2.0).7

and anticoagulation in labor, postpartum (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparins UFH has a short half-life and must be

and beyond. A round-table discussion of (LMWHs), factor-Xa inhibitors, and di- administered subcutaneously or via con-

all topics by all participants followed, from rect thrombin inhibitors. tinuous infusion.17 The current treat-

which an original outline resulted. Based Warfarin, a coumarin derivative, in- ment guidelines recommend subcutane-

on the outline, this report was drafted, re- teracts with many other medications. ous dosing of UFH every 12 hours; either

fined, and agreed on after multiple review as a low dose of 5000 U, to achieve target

Because of the physiologic changes asso-

rounds after the meeting was held. The anti-Xa between 0.1 and 0.3 U/mL

ciated with pregnancy as well as nausea

working group maintained full and inde- (moderate dosing), or to achieve target

and vomiting, it is difficult to attain sta-

pendent responsibility for content of the midinterval aPTT into the therapeutic

ble anticoagulation with this drug. Use of

consensus document. range (adjusted dosing).7 It requires fre-

the drug during the first trimester has

This report provides a concise update quent laboratory monitoring and dosage

been associated with spontaneous abor-

for practitioners in maternal and fetal adjustment. Although UFH can be re-

health. Recommendations for the use of tion and warfarin embryopathy, consist- versed by protamine sulfate, its use is

antithrombotic drugs in pregnancy are ing of mental retardation, optic atrophy, complicated by the potential for bleed-

given throughout the report. Recommen- microphthalmia, cataracts, ventral mid- ing complications (probably due to its

dation grades A to C and evidence levels I line dysplasia, nasal hypoplasia, stippled effect on factor IIa resulting in inhibition

to III are based on the US Preventive Ser- bones and epiphyses, and central ner- of prothrombin activity and an anticoag-

vices Task Force grading of evidence (Ta- vous system (CNS) abnormalities in ap- ulant effect). Although heparin-induced

ble 1).11 In brief, grade A recommenda- proximately 4-5% of exposed fetuses. thrombocytopenia (HIT) is infrequently

tions and level I evidence come from Frequencies of abnormalities up to 29% reported in pregnancy, it remains a con-

randomized controlled trials with clear re- have been reported in patients requir- cern, as up to 5% of individuals treated

sults; grade B recommendations and level ing warfarin for mechanical heart with standard heparin develop this com-

II evidence come from well-designed non- valves.12-14 Moreover, warfarin can plication, which is associated with a high

randomized studies with limited or incon- cause CNS abnormalities after exposure thrombosis risk. Long-term use of UFH

sistent evidence; and level III evidence and at any stage during pregnancy. Warfarin has been reported to cause osteoporosis,

grade C recommendations result from readily crosses the placenta and results in which is a concern in patients who re-

consensus opinions of respected experts fetal anticoagulation that is not readily quire treatment throughout their preg-

and authorities based on clinical experi- reversible, resulting in an increased risk nancy.17 UFH is classified by the Food

ence and descriptive studies. of intracranial hemorrhage.15 Warfarin and Drug Administration (FDA) as a

457.e2 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2007

www.AJOG.org Obstetrics Review

pregnancy category C drug. It does not other comparator regimens containing who require anticoagulation for mater-

cross the placenta and is considered safe UFH (intravenous [IV] UFH followed nal indications, and those who require

for the fetus when used during preg- by LMWH, IV UFH, followed by subcu- anticoagulation for the prevention of ad-

nancy. UFH is not secreted in breast milk taneous [SC] UFH and SC UFH). The verse pregnancy outcomes (APOs).

and can be used by nursing mothers.7 lower incidence of adverse events re- Pregnant women may have more than 1

LMWHs are administered subcutane- sulted in lower overall treatment costs indication for anticoagulation since the

ously either once or twice daily for the for the LMWH regimen.29 underlying medical illness may predis-

prevention or treatment of VTE. They Factor-Xa inhibitors are a relatively new pose to APOs that may be amenable to

have considerable theoretical benefits class of anticoagulants. Fondaparinux be- anticoagulant therapy.

over UFH, including better bioavailabil- came the first drug in this class to gain FDA

ity,18,19 longer plasma half-life (or higher approval for the prevention of VTE in ma-

anti-factor-Xa activity),20 more predict- jor orthopedic surgery and for the treat- Maternal thromboembolism

able pharmacokinetics and pharmaco- ment of acute VTE. Fondaparinux is la- 1.1 History of VTE. The risk of VTE in

dynamics,21 less potential to cause osteo- beled as a pregnancy category B drug. pregnancy ranges from 0.05% to 1.8%,

porosis,22 and lower incidence of HIT.23 Animal reproduction studies have demon- with a rate of recurrent VTE of 1.4-

LMWHs inhibit factor Xa more effec- strated no harm to the fetus or to fertility, 11.1%.46-48 Levels of coagulation activa-

tively than factor IIa to produce their an- although fondaparinux was found to be se- tion markers such as prothrombin frag-

tithrombotic effect.24 Many data are creted in breast milk in these studies.30 No ment 1.2 (PF1.2) and thrombin-

available supporting the use of LMWH adequate clinical data exist on the use of antithrombin complex (TAT) increase

over UFH for the treatment of acute VTE fondaparinux in pregnant women.30 with the progression of pregnancy to lev-

in nonpregnant patients,25 and monitor- Several direct thrombin inhibitors are els seen in patients with active thrombo-

ing anticoagulation intensity or dosage approved for clinical use in the United sis.49 Therefore, women in the later

adjustments are generally unnecessary States. Lepirudin, bivalirudin, and argatro- stages of pregnancy often require an in-

with LMWH in these populations. How- ban are labeled by the FDA as pregnancy crease in the dose of UFH to maintain

ever, pregnant patients can present an category B drugs.31-33 Animal studies have therapeutic levels of anticoagulation.50

exception to this rule because the phar- demonstrated no evidence of impaired fer- Brill-Edwards et al46 addressed the

macokinetics of LMWHs can change tility or harm to the fetus. However, animal safety of withholding heparin treatment

during pregnancy.7 The increased renal studies have shown that lepirudin can in 125 pregnant women with a history of

clearance and changes in maternal cross the placenta31 and argatroban has VTE occurring more than 3 months be-

weight over the course of pregnancy may been detected in breast milk.32 It is not fore the current pregnancy. An antepar-

necessitate higher and more frequent known, definitively, whether these drugs tum recurrence of VTE occurred in 2.4%

dosing than in the nonpregnant individ- are secreted in human breast milk. Cur- of these patients. No recurrences oc-

ual. LMWHs are cleared from the body rently there are no adequate clinical data curred in the 44 women without evi-

partially via a nonsaturable (renal) route on the use of direct thrombin inhibitors in dence of thrombophilia or with a tempo-

of elimination.26 Pregnancy is character- pregnant women. rary risk factor associated with the

ized by initial increase in glomerular previous episode, whereas 5.9% of 51 pa-

filtration rate with a subsequent decre- tients with thrombophilia or an idio-

ment at term. Protamine only reverses

R ISK A SSESSMENT pathic VTE had an antepartum recur-

The hemostasis changes in pregnancy

the anti-IIa activity of LMWH com- rence. A subsequent study by Pabinger et

that tend to create a prothrombotic mi-

pletely, whereas the anti-Xa activity is al51 also found that the risk of symptom-

lieu have been well documented.34-42

not fully neutralized (maximum reversal atic VTE recurrence was 3-fold higher

Pregnancy is associated with a 20-200%

⬃60%).26 LMWHs are classified by the during pregnancy, but that temporary

increase in levels of fibrinogen and fac-

FDA as a pregnancy category B drug. risk factors (such as trauma, surgery or

tors II, VII, VIII, X, and XII.43 Decreases

They do not cross the placenta and are immobilization) at the first event did not

occur in both the natural anticoagula-

safe for the fetus.7,27 LMWHs are not se- differentiate clearly between women at

tion system, such as decreases in protein

creted in breast milk and can therefore high risk or low risk of a pregnancy-as-

S levels,41 and in the fibrinolytic process,

be safely used by nursing mothers.7 The sociated VTE recurrence. These data

evidenced by increases in plasminogen-

safety profile of LMWHs has been fur- suggest that not all pregnant women

activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) and 2 (PAI-

ther confirmed in a recent systematic re- with a previous VTE need be treated with

2)44 and thrombin-activatable fibrinoly-

view encompassing 64 reports on 2777 prophylactic anticoagulants. They also

sis inhibitor (TAFI) levels.45

patients.28 Furthermore, a recent study indicate that the presence of thrombo-

confirmed that consistent administra- philia or previous idiopathic VTE is a

tion of LMWH during both the acute I DENTIFICATION OF P ATIENTS risk factor for VTE.

and long-term therapy for VTE during AT R ISK OF VTE 1.2 Inherited thrombophilic condi-

pregnancy was associated with lower Potential candidates for anticoagulation tions. Inherited thrombophilias are a

rates of adverse events compared with 3 in pregnancy can be classified as patients heterogeneous group of disorders in-

NOVEMBER 2007 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 457.e3

Review Obstetrics www.AJOG.org

TABLE 2

Thrombophilia and thromboembolism1

VT/VTE in pregnancy or

Inherited thrombophilia General incidence VT or VTE puerperium

AT deficiency (most thrombogenic) 0.02-0.17% 50% life chance of VTE 50% chance VTE in

1% in patients with VTE pregnancy

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

APCR or factor V Leiden* 3-7% of white women Incidence of 20-30% with VTE APCR found in 78% with VTE

Factor V Leiden in 46% with

VTE (predictive value

1:500)

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

†

Protein S or C deficiency 0.14-0.5% Found in 3.2% with VTE Protein S 0-6%

Protein C 3-10%

Postpartum:

Protein S 7-22%

Protein C 7-19%

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Factor V Leiden and PGM G20210A Predictive value 4.6:100

Prevalence in VTE 9.3% vs 0

in control group

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Hyperhomocysteinemia/homozygous MTHFR 8-10% of healthy population Increased risk NA

(C677T/A1298C)

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

APCR, activated protein C resistance; NA, not available; PGM, prothrombin gene mutation; VT, venous thrombosis.

* Includes causes other than factor V Leiden for resistance to APC.

†

Protein S levels decrease in pregnancy to below normal standard reference range.

cluding deficiencies of protein S, protein Other inherited thrombophilic muta- TAFI.45 There is a high incidence of in-

C, and antithrombin (AT). In 1994, an tions, including methylene tetrahydro- sulin-resistance syndrome (also known

association between a mutation in the folate reductase (MTHFR) C677T and as metabolic syndrome or syndrome X)

factor V gene and increased thrombotic A1298C (often associated with hyperho- in obese patients. A core feature of this

risk was first reported.52 This mutation is mocysteinemia) and PAI gene mutations syndrome is elevated plasma levels of

present in 5% of American white, 1% of 4G/4G, 4G/5G, and 5G/5G, have been PAI-1,71 the primary inhibitor of both

African American, and 5-9% of Euro- weakly associated with pregnancy com- tissue-type plasminogen activator

pean populations, but is rare in Asian plications.59-61 The MTHFR mutations (t-PA) and urokinase-type plasminogen

and African populations.53,54 The factor have been associated with neural tube activator (u-PA), which limits the fi-

V mutation is associated with resistance defects, and other malformations. brinolytic process.70 Low-dose aspirin

to activated protein C (APC) and is in- Data from several studies suggest that reduces plasma levels of PAI-1 in preg-

herited primarily in an autosomal-dom- abnormalities in the natural anticoagu- nant patients.72

inant fashion.54,55 Heterozygosity is lation system, such as AT deficiency, Data from several studies indicate

found in 20-40% of nonpregnant pa- APC resistance, and protein S or C defi- adverse outcomes associated with obe-

tients with thromboembolic disease, ciency, induce varying degrees of in- sity in pregnant women.73,74 The com-

whereas homozygosity confers a more creased risk for thrombosis in pregnancy bination of pregnancy and obesity

than 100-fold increased risk of thrombo- and the puerperium (Table 2).1,57,62-65 would logically be considered a com-

embolic disease.54 More recently, the Although heterozygous factor V Leiden pounded hypercoagulable and pro-

prothrombin gene mutation (pro- and prothrombin G20210A have lower thrombotic state. Sebire et al73 studied

thrombin G20210A) has been found to hazard ratios for thrombosis, they are by 287,213 singleton pregnancies. Com-

increase circulating prothrombin lev- far the most commonly noted mutations pared with women with normal body

els48 and hence the risk of both throm- associated with thrombosis and adverse mass index (BMI 20-24.9 kg/m2),

bosis50 and pregnancy complications.56 outcomes in pregnancy.49,66-68 obese women (BMI ⬎ 25 kg/m2) were

In women with a history of VTE during 1.3 Obesity. Obesity has been associ- significantly more likely to develop

pregnancy, prothrombin G20210A was ated with higher risk of atherothrom- gestational diabetes mellitus and pro-

found in 17% of patients compared with botic disease and VTE in the general teinuric preeclampsia, to have induced

1% of age-matched controls.57 Homozy- medical population.69 Multiple aspects labor, to undergo emergency cesarean

gosity for prothrombin G20210A is of obesity aggravate the prothrombotic delivery, and to experience postpartum

thought to confer an equivalent risk of risk in pregnancy. The fibrinolytic pro- hemorrhage, genital tract infection,

VTE to that of factor V Leiden cess is decreased, as manifest by in- urinary infection, wound infection,

homozygosity.58 creased levels of PAI-1, PAI-2,70 and birth weight greater than the 90th per-

457.e4 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2007

www.AJOG.org Obstetrics Review

TABLE 3

Clinical risk factors for VTE (ORs with CIs)

Lindqvist et al37 Danilenko-Dixon et al77 Anderson and Spencer78

(N ⴝ 603) (N ⴝ 90) (N ⴝ 1231)

Moderate-risk factors

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Age ⱖ 35 y 1.3 (1-1.7) 2.0 (age ⬎ 40 y)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Parity

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

2 1.5 (1.1-1.9) 1.1 (0.9-1.4)

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

ⱖ3 2.4 (1.8-3.1)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Smoking 1.4 (1.1-1.9) 2.5 (1.3-4.7)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Multiple gestation 1.8 (1.1-3.0) 7 (0.4-135.5)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Preeclampsia 2.9 (2.1-3.9) 1 (0.14-7.1)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Varicose veins 2.4 (1.04-5.4) 4.5

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Obesity 1.5 (0.7-3.2) ⬍2

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Cesarean section 3.6 (3.0-4.3)

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Obstetric hemorrhage 9 (1.1-71.0)

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

High-risk factors

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Spinal cord injury ⬎ 10

.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Major abdominal surgery ⱖ 30 min ⬎ 10

centile, and intrauterine death. This 2. Moderate risk: Patients undergo- prolonged immobilization, which is

population of patients may benefit ing a minor procedure with general known to be a risk factor for VTE in

from screening for common thrombo- anesthesia for more than 30 min- the absence of pregnancy. Therefore,

philic mutations such as factor V Lei- utes and are 40-60 years old or have prolonged bed rest under these con-

den, prothrombin G20210A, MTHFR additional risk factors. Patients ditions may also place pregnant

C677T/A1298C, as well as functional younger than 40 years with no ad- women at a higher risk of VTE. Fur-

protein S and C, and AT deficiency, al- ditional risk factors and undergo- thermore, other moderate risk factors

though few data currently exist as to ing major surgery. should also be considered including

the benefit of screening in obese pa- 3. High risk: Patients older than 40 age older than 35 years, smoking, mul-

tients. Further studies are necessary to years or with additional risk factors tiple gestation, and preeclampsia, as

determine whether this population undergoing major surgery. Pa- outlined in Table 3.37,77,78

should be screened. The risk-benefit tients undergoing minor surgery 2. Adverse pregnancy outcomes.

ratio of prescribing heparin or low- who are older than 60 years or have After excluding congenital birth defects

dose aspirin to high-risk obese patients additional risk factors. and idiopathic preterm delivery, severe

who have not had a VTE requires fur- preeclampsia at 36 weeks or less, intra-

ther investigation. 1.5 Family history. As many throm- uterine growth retardation (IUGR), fetal

1.4. Surgery. Pregnancy adds an ad- bophilic states are inherited, patients loss at 20 weeks’ gestation or more, and

ditional hypercoagulable state to the with a family history of VTE may be at abruption account for three-quarters of

thrombotic risks associated with surgery. increased risk for VTE. The risk is further all cases of fetal mortality and/or mor-

In general the risk of fatal PE is 0.2-0.9% increased in the presence of thrombo- bidity, with a prevalence of approxi-

in patients undergoing elective sur- philic conditions. Specifically, the risk is mately 8% (Table 4).79

gery.75 Risk factors include advanced increased approximately 8-fold for AT Numerous studies examining the as-

age, a history of VTE, obesity, heart fail- deficiency, 7-fold for protein C defi- sociation between inherited thrombo-

ure, paralysis, or thrombophilia.75 Surgi- ciency, and doubled for factor V Leiden philias and adverse reproductive out-

cal risk has been classified into the fol- mutation.76 comes have been performed. However,

lowing 3 categories:75 1.6. Other risk factors. Bed rest is of- there are no clear conclusions to be

ten recommended to pregnant women drawn from these studies, as some show

1. Low risk: Patients under the age of with threatened preterm labor, pre- a positive relationship between throm-

40 years, no additional risk factors, eclampsia, and/or signs of uteroplacental bophilias and adverse outcomes,

and undergoing minor procedure. insufficiency. However, this involves whereas others show no association.

NOVEMBER 2007 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 457.e5

Review Obstetrics www.AJOG.org

TABLE 4

Prevalence and risk of recurrence of APO without thrombophilia

Previous pregnancy Prevalence of pregnancy Pregnancy complication in Fetal death with pregnancy

complication complication (%) subsequent pregnancy (%) complication (%)

Fetal loss after or at 20 wks 0.5 8.5 8.5

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Severe preeclampsia 2 26 13.5

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

HELLP 1 4 13.5

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Eclampsia 0.5 3 13.5

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Abruption 0.8 5 26

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

IUGR ⱕ 5th percentile 5.3 16 20

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

One or more 8 61-85 —

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Reprinted from Paidas et al79 with permission from Elsevier.

Some of the most widely quoted studies noted between IUGR and prothrombin There is more evidence suggesting that

demonstrating a positive association are G20210A (OR 5.7, 95% CI, 1.2-27) and loss of the conceptus in the fetal period

flawed by the small number of patients or protein S deficiency (OR 10.2, 95% CI, (loss of the fetus documented to have been

the use of composite outcomes.56,80 Sys- 1.1-91).82 alive at or beyond 10 weeks’ gestation) is

tematic reviews have evaluated the associ- It is difficult to determine the rela- associated with thrombophilias,100,102-104

ation between factor V Leiden or the pro- tionship between thrombophilias and though negative studies also exist.105 Most

thrombin gene mutation G20210A and abruptio placentae. This is due to the case-control and cohort studies suggest a

IUGR.81-83 Both mutations confer an in- presence of confounding variables, such 2- to 4-fold increase in the rate of throm-

creased risk of giving birth to a growth-re- as chronic hypertension,96,97 and be- bophilias among women with a history of

stricted infant (factor V Leiden: odds ratio cause it is often observed in the setting of fetal death, especially in those with more

[OR] 2.7, 95% CI 1.3-5.5; prothrombin other APOs, such as preeclampsia, than 1 episode.100,102,106-108 In contrast,

G20210A mutation: OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.3- IUGR, and fetal death. For example, 29% many studies of the general obstetric pop-

5.5), but the association may be driven by of patients with abruption had a protein ulation have found a weaker association

small studies of poor quality that demon- S deficiency compared with 0.2-2% in between thrombophilia and recurrent

strated extreme associations.81 the general population.97 Systematic re- pregnancy loss.109-111 Uteroplacental

Several studies, most of which were views do suggest an association between thrombosis is a common feature in preg-

case controlled, have examined the rela- factor V Leiden and abruptio placentae, nancies with unexplained late fetal loss102

tion between heterozygous factor V Lei- but this is based on few studies with con- and could theoretically be reduced by hep-

den and severe preeclampsia.56,80,83-93 founding factors and low numbers of arin thromboprophylaxis, which may help

Factor V Leiden was identified in be- patients.82,83 to prevent a recurrence by decreasing vas-

tween 5% and 26% of patients with se- Studies of the possible relationship cular injury and thrombin generation and

vere preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP between thrombophilia and pregnancy further reducing thrombosis in the utero-

syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver en- loss are plagued by differences in the def- placental circulation.

zymes, low platelets).56,84-87,93-95 In a initions used for miscarriage and fetal Protein Z levels at the 20th percentile

systematic review of 18 preeclampsia death, the methods used to select pa- (1.30 g/mL) are also associated with an

studies,82 a positive association between tients, and the lack of appropriate, eth- increased risk of APO (OR 4.25, 95% CI

factor V Leiden and preeclampsia or nicity-matched controls. Most research 1.54-11.76, sensitivity 93%, specificity

eclampsia (OR 1.6, 95% CI, 1.2-2.1) was suggests that thrombophilias (AT defi- 32%).112 In the same group of patients,

found. ciency, protein C or S deficiency, factor V protein S levels were significantly lower in

In the largest study published to date Leiden, prothrombin G20210A, and the the second and third trimesters in patients

involving women whose infants had most common MTHFR mutation) are with APO compared with patients with

IUGR (defined as ⬍ 10th percentile), the not associated with loss of the conceptus normal pregnancy outcome (34.4 ⫾

prevalence of factor V Leiden was 4.5% or recurrent miscarriage before 10 11.8% vs 38.9 ⫾ 10.3% and 27.5 ⫾ 8.4% vs

and of prothrombin G20210A was weeks’ gestation (preembryonic or em- 31.2 ⫾ 7.4%, respectively, for the second

2.5%.59 Prevalence rates ranging from bryonic losses).98,99 At the same time, and third trimesters; P ⬍ .05 for both),

5% to 35% for factor V Leiden, 2.5% to other investigators have reported that suggesting that decreased protein S and Z

15% for prothrombin G20210A, and 1% untreated women with recurrent mis- levels are additional risk factors for APO.

to 23% for protein S deficiency have also carriage and factor V Leiden have partic- To further clarify the prothrombotic ele-

been reported. In a systematic review of 3 ularly poor subsequent pregnancy ments involved, Laude et al113 studied

studies, significant associations were outcomes.100,101 women with a history of recurrent preg-

457.e6 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2007

www.AJOG.org Obstetrics Review

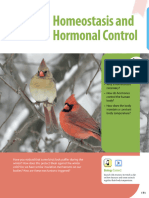

FIGURE

Figure risk assessment and prevention of VTE and APOs in pregnant patients

Thrombophilia screening for patients with:

a history of VTE; history of unexplained fetal loss

Risk assessment ≥ 20 weeks, severe preeclampsia/HELLP, severe

IUGR, or family history of thrombosis

Low risk Moderate risk High risk Highest risk

• Transient risk factors • History of APO: severe • History of idiopathic VTE • History of antiphospholipid

• Family history of VTE preeclampsia, IUGR < 5th outside of pregnancy without antibody syndrome

• History of APO: severe percentile, fetal loss at ≥ 20 identifiable risk factors • Active arterial and/or venous

preeclampsia, IUGR < 5th weeks • History of VTE with thromboembolism

percentile, fetal loss at ≥ 20 • History of VTE with transient thrombophilia (factor V Leiden, • Known antithrombin deficiency

weeks risk factors including prothrombin G20210A, • Homozygotes or compound

pregnancy functional protein C/S heterozygotes for factor V Leiden

• Thrombophilia with family deficiency or antithrombin) or prothrombin mutations

history of VTE • History of antiphospholipid

antibody syndrome (criteria

met by recurrent pregnancy

Prevention of VTE loss only) Prevention of VTE/APO

• Possible intrapartum • Therapeutic anticoagulation

antithrombotic compression mandatory during pregnancy and for

Prevention of VTE

boots ≥ 6 weeks during postpartum

• Postpartum enoxaparin 40 • Enoxaparin 1 mg/kg BID or dalteparin

mg SC QD, 30 mg BID* or 200 U/kg QD

dalteparin 5,000 U SC QD Prevention of VTE/APO ‡

• Weekly peak and trough monitoring of

Prevention of APO • Antepartum enoxaparin 40 mg anti-Xa levels, adjusting dose to keep

• Antepartum enoxaparin 40 SC QD, 30 mg BID* or peak anti-Xa at 0.8−1.0 IU/mL and

mg SC QD or dalteparin dalteparin 5,000 U SC QD trough anti-Xa at ≥ 0.5 IU/mL†

5,000 U SC QD May require BID dosing • Postpartum anticoagulation: target

• Assessing anti-Xa levels each INR 2.5-3.5 for 4-6 weeks with initial

trimester is an option overlap of UFH or LMWH until INR

• Postpartum treatment in ≥ 2.5

patients with a history of VTE

Monitoring guidelines for patients treated with LMWH or UFH

1. Anti-factor Xa assay: target peak range (3-4 hours after dosing) is 0.2-0.4 IU/mL for prophylaxis and 0.5-1.0 for treatment (upper range for treatment 0.8-1.0 IU/mL).

Target trough range (12 hours after dosing) 0.1-0.3 IU/mL for prophylaxis and 0.2-0.4 IU/mL (> 0.5 IU/mL if highest risk) for treatment.

2. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia: check platelet counts at start of treatment with heparin, then weekly for 3 weeks.

3. During in-hospital treatment for VTE, fetal surveillance is recommended.

Treatment recommendations based on empiric evidence from the consensus panel

*The choice of enoxaparin dose should be tailored according to the individual patient as these doses have not been compared in this setting.

†

The dose of enoxaparin may be increased to maintain peak level at the top end of the desired range.

‡

Aspirin and heparin are recommended in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies.

Duhl. Antithrombotic therapy and pregnancy. AJOG 2007.

nancy loss or late fetal demise (⬎ 10th tive use, trauma, obesity, cancer, or under- or a family history of thrombosis. Evidence

week) and their levels of circulating proco- lying medical conditions, may benefit in favor of this practice is limited but accu-

agulant thrombin-generating micropar- from being screened for thrombophilia mulating at present. The prospective ran-

ticles. Of the patients, 59% in the early (Figure). Screening patients with a first domized trial by Gris et al114 firmly sug-

pregnancy-loss group (⬍ 10 weeks) and VTE for thrombophilias is currently the gests a potential treatment benefit in

48% in the late fetal-demise group had in- subject of considerable study and debate. screening women with otherwise unex-

creased levels of microparticles. The Though encouraged by some clinicians, plained fetal death for factor V Leiden,

women were not pregnant at the time of routine testing for thrombophilias may be prothrombin G20210A, and functional

the assessment and these findings would of limited clinical value. In contrast, pa- protein S deficiency.

indicate an ongoing preexisting pro- tients presenting with recurrent thrombo- The basic tests for thrombophilia

thrombotic state that may be further en- sis or with thrombosis in the setting of a screening include functional protein C,

hanced during pregnancy. strong family history of VTE may be can- functional protein S, antithrombin III

didates for thrombophilia testing. (AT-III) (functional assay), APC resis-

S CREENING FOR Some obstetricians have recommended tance (or factor V Leiden [polymerase

T HROMBOPHILIA thrombophilia screening in women with chain reaction]), and prothrombin

Patients with a history of thrombosis, unexplained fetal loss at 20 weeks’ gesta- G20210A [polymerase chain reaction]).

whether it is of idiopathic origin or associ- tion or longer, severe preeclampsia or Other screening for acquired thrombo-

ated with pregnancy, with oral contracep- HELLP, severe IUGR (⬍ 5th percentile), philic conditions can include testing for

NOVEMBER 2007 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 457.e7

Review Obstetrics www.AJOG.org

TABLE 5

Heparin administration to prevent APO

Author N Drug Patients studied Outcome

Riyazi et al133 26 Nadroparin ⫹ ASA 80 mg Thrombophilia plus prior preeclampsia or Treatment associated with lower rates of

IUGR preeclampsia/IUGR compared with

historical control

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

134

Brenner et al 50 Enoxaparin Thrombophilia plus recurrent fetal loss Treatment associated with higher live birth

rate compared with historical control

(75% vs 20%)

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

135

Ogueh et al 24 UFH Thrombophilia plus IUGR or abruption No improvement compared with historical

control.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Kupferminc et al 136

33 Enoxaparin ⫹ ASA 100 Thrombophilia plus preeclampsia or IUGR Higher birth weight and gestational age at

mg delivery compared with previous

untreated complicated pregnancies.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

137

Grandone et al 25 UFH or enoxaparin Thrombophilia plus APO/ Treatment was associated with lower rates

of APO in treated (10%) vs nontreated

(93%) patients.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

138

Brenner 183 Enoxaparin Thrombophilia plus recurrent fetal loss Treatment was associated with increased

rate of live birth, and decreased rate of

preeclampsia and abruption compared

with historical control.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Paidas et al 139

41 Enoxaparin, dalteparin, or Thrombophilia plus APO ⬃80% risk reduction in APO compared

UFH with untreated pregnancies.

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

114

Gris et al 160 Enoxaparin or aspirin Thrombophilia plus unexplained fetal loss Enoxaparin was associated with higher live

birth rates (86%) compared with aspirin

(29%).

anticardiolipin antibodies immuno- tion or longer, severe preeclampsia/ Typically, patients at highest risk are

globulin G (IgG) and IgM, and lupus an- HELLP at less than 34 weeks’ gestation, on coumarin before pregnancy and ide-

ticoagulant. However, not all of these an- severe IUGR, or a family history of ally should be converted to LMWH be-

tibodies need to be drawn. A platelet thrombosis may benefit from thrombo- fore conception or as soon as the patient

count can be used to screen for throm- philia screening.114 The basic screening presents for care. Previous guidelines

bocytosis and related disorders. Further tests include factor V Leiden mutation, have recommended that target peak an-

supplemental screening may consist of prothrombin G20210A mutation, func- ti-Xa levels (measured 4 hours after a

homocysteine, other factor V mutations, tional protein C and S deficiencies, AT- subcutaneous dose) should be 1.0-1.2

thrombomodulin gene variants, protein III deficiency, lupus anticoagulant, ho- IU/mL.5 Therapeutic anticoagulation

Z levels, PAI-1 activity levels, PAI-1 mocysteine level, and anticardiolipin should be considered in high-risk

4G/5G polymorphisms, MTHFR, ho- antibodies.79 (Level IIIC) women during pregnancy but using pro-

mocysteine PAI-1 polymorphisms, and phylactic dosing and less frequent mon-

factor evaluation (VII, VIII, IX, XI). itoring than in the highest-risk group.

Currently, the costs of routine thrombo- R ISK A SSESSMENT AND The prophylactic and therapeutic doses

philia screening for all patients are prohib- A NTITHROMBOTIC for the most commonly used LMWHs

itive. Clearly, more evidence-based data R ECOMMENDATIONS D URING are illustrated in Table 5.24 Because of the

from prospective randomized trials evalu- P REGNANCY altered pharmacokinetics of heparin me-

ating the use of anticoagulation for the pre- Patients can be classified according to tabolism in pregnancy,18,115-117 dosage

vention of APOs are needed before these their risk for VTE, their risk of an APO, adjustment may be necessary to achieve

costs can be justified. or both. Antithrombotic recommenda- desired adequate peak or trough anti-Xa

tions are based on an assessment of an levels and thus monitoring for therapeu-

C ONSENSUS P ANEL individual patient’s level of risk, and are tic anticoagulation is suggested. Dosing

R ECOMMENDATIONS outlined in the Figure. It should be em- adjustment is also needed to achieve ad-

FOR T HROMBOPHILIA phasized that the risk categories and equate levels in obese patients. If UFH is

S CREENING treatment regimens are based on level II used for therapeutic anticoagulation,

● Patients with a history of thrombosis, and III studies and/or extrapolated from higher doses and 3 times daily dosing are

unexplained fetal loss at 20 weeks’ gesta- level I nonpregnant studies. usually required to maintain adequate

457.e8 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2007

www.AJOG.org Obstetrics Review

TABLE 6

Prophylactic and therapeutic doses for the most commonly used LMWHs

Proprietary name, Anti-factor-Xa/IIa Prophylactic dosage Therapeutic dosage

LMWH manufacturer activity for VTE for VTE

Enoxaparin sodium Lovenox, Sanofi-Aventis 2.7/1 40 mg (4000 IU) QD 1 mg (100 IU)/kg BID

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Dalteparin sodium Fragmin, Pfizer Corporation 2.1/1 2500-5000 IU QD or 2500 IU BID 100 IU/kg BID

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Nadroparin calcium Fraxiparin, GlaxoSmithKline 3.2/1 3075 IU QD 170 IU/kg QD or BID

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Tinzaparin sodium Innohep, LEO Pharma 1.9/1 2500-4500 IU QD 175 IU/kg QD

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Ardeparin sodium Normiflo, Wyeth-Ayerst 2.0/1 100 IU/kg per day BID NA

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Reviparin sodium Clivarin, Knoll AG 3.5/1 1432-3436 IU antifactor Xa QD 142 IU/kg BID

................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

NA, data not available.

Adapted from Laurent et al24 with permission from Wolters Kluwer Health.

anticoagulation peak levels to rise the ac- available in clinical laboratories. Most lab- such as cesarean delivery, bed rest, or the

tivated partial thromboplastin time oratories that offer this test have it set up postpartem period, creates a very differ-

(aPTT) to 2-2.5 times normal.118 for 1 of the LMWHs (eg, enoxaparin, ent approach to thromboprophylaxis

Women at moderate risk may be offered which has a recommended therapeutic compared with the nonpregnant state.

prophylactic doses of LMWH (Figure), range of 0.5-1.0 anti-Xa units/mL and a Dosages and monitoring guidelines for

with 2500-5000 IU dalteparin twice daily prophylactic range of 0.2-0.4 IU/mL). As nonpregnant women cannot be extrapo-

(BID), 40 mg enoxaparin once daily (QD), the various LMWHs have different factor lated accurately to pregnant women. All

or 30 mg enoxaparin BID. Although the Xa/IIa activity (Table 5),24 the test must be protocols and regimens of thrombopro-

relative efficacy of these 2 enoxaparin calibrated for the drug in question. For ex- phylaxis in pregnancy entail extensive

doses has not been studied, and the use of ample, a factor Xa assay set up for enox- patient and clinician interaction. Modi-

40 mg enoxaparin QD is common prac- aparin should not be used interchangeably fications during pregnancy are common,

tice, members of the consensus panel have for another LMWH or anti-Xa drug, as it and treatment plans need to be individ-

divided opinions for the choice of dose, may give erroneous readings. ualized with informed consent between

based on the pharmacokinetic properties patients and their physicians.

of LMWH in pregnancy.7 Until studies P REVENTION AND C OUNSELING

comparing the 2 regimens are published, FOR VTE

clinicians should choose the most appro- Current recommendations for throm- H OW TO M ANAGE P ATIENTS

priate regimen for their patient and her boprophylaxis during pregnancy are W ITHOUT P RIOR VTE OR

clinical situation. Some investigators aim based largely on case series and extrapo- T HROMBOPHILIA

to achieve peak anti-Xa levels (3-4 hours lation from studies of nonpregnant pa- Thromboprophylaxis in pregnancy is ac-

after dosing) ranging from 0.2-0.4 IU/mL tients. Because of the incidence of recur- complished primarily with self-adminis-

but, in general, monitoring is not necessary rent VTE being low, studies need to be tered subcutaneous UFH or LMWH.

for these patients. Women at low risk may extremely large to obtain sufficient However, because thromboprophylaxis

not need antepartum prophylaxis, but power to demonstrate the efficacy of any carries a risk of bleeding, HIT, and osteo-

some authors recommend postpartum strategy and thus far, such a randomized porosis when given for prolonged peri-

prophylaxis ranging from 3 days to 6 prospective trial in pregnancy has not ods, its use may only be justified or cost

weeks, particularly in obese women and been done. In the nonobstetric litera- effective in selected pregnant women.

women with cesarean birth.24,43 ture, thromboprophylaxis is prescribed Nevertheless, pregnant women with 1

to protect patients during short periods high-risk factor or multiple (⬎ 3) mod-

M ONITORING OF P ATIENTS ON covering specific vulnerable events such erate-risk factors for VTE (Table

LMWH OR F ACTOR -X A as orthopedic surgery. In pregnancy, 3)37,77,78 are considered for thrombo-

I NHIBITORS thromboprophylaxis is given for pro- prophylaxis in the United Kingdom119

Where monitoring is indicated, an anti-Xa longed periods because pregnancy and (Table 6),119 although more data are re-

assay must be used because the aPTT is in- the puerperium is a hypercoagulable quired before this approach can be ac-

sensitive to LMWHs and Xa inhibi- state lasting approximately 308 days cepted in the United States. The Confi-

tors.26,29 Most commonly, anti-Xa-activ- from conception until 6 weeks after de- dential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths

ity assays involve setting up a standard livery. Maintaining a constant level of in the United Kingdom revealed that,

curve using the drug in question and mea- anticoagulation, with changing renal when maternal death occurred due to

suring drug activity using a chromogenic clearance, increasing weight, and super- VTE, 1 or more of these risk factors was

substrate, but this test is not routinely imposed periods of even higher risk, present in 80% of the women.120

NOVEMBER 2007 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 457.e9

Review Obstetrics www.AJOG.org

1. Thromboprophylaxis during ce- ion of the Working Group mechanical with UFH or LMWH administered ante-

sarean delivery. Thromboprophylaxis thromboprophylaxis may be considered natally and during the 6 weeks postpar-

during cesarean delivery is not widely and perhaps recommended in patients tum may be an appropriate option for

used in the United States. Expert pan- with multiple risk factors. some patients. Patients should also be

els8,75 have published recommendations encouraged to regain mobility after

for thromboprophylaxis in pregnancy C ONSENSUS P ANEL childbirth, but in individuals in whom

but they do not specifically address ce- R ECOMMENDATIONS FOR this is not possible, compression stock-

sarean delivery. In 1995, the Royal Col- M ANAGING P ATIENTS W ITHOUT ings could be worn.

lege of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists P RIOR VTE OR 3. How to manage patients with a his-

(RCOG) published recommendations T HROMBOPHILIA tory of 2 or more VTEs. Few data are

for thromboprophylaxis during cesarean available to suggest that, if a person has

delivery (Table 6),119 but only one fifth ● Thromboprophylaxis use in all preg- had 2 or more episodes of idiopathic

of physicians in the United Kingdom nant patients without prior VTE or VTE, she will be at increased risk of VTE

were found to be following them. As a thrombophilia may only be justified or during pregnancy. Theoretically, this

consequence, the RCOG now recom- cost effective in selected pregnant pa- group of patients may have an even

mends that all women undergoing cesar- tients.121 (Level IIIC) higher risk of VTE compared with pa-

ean delivery should receive heparin ● There are insufficient data to recom- tients with no history and so may already

thromboprophylaxis.120 mend routine pharmacologic prophy- receive lifelong anticoagulation. If not,

Currently, only 4 prospective random- laxis in patients undergoing cesarean then antenatal and postpartum prophy-

ized trials of thromboprophylaxis during delivery.121 (Level II-2B) lactic anticoagulation with UFH or

cesarean delivery have been published, and ● Intermittent pneumatic compression LMWH124,125 and patient counseling

none are of adequate size to determine may be considered in patients under- should be mandatory in these patients.

whether thromboprophylaxis for routine going cesarean delivery with multiple However, the patient must be informed

cesarean delivery is warranted.121 Simi- VTE risk factors.123 (Level IIIC) of the limited amount of data available to

larly, the effectiveness of nonpharmaco- support the use of anticoagulants in this

logic mechanisms of thromboprophylaxis, H OW TO M ANAGE P ATIENTS setting.

such as venous compression stockings and W ITH A H ISTORY OF VTE 4. How to manage patients with prior

pneumatic compression boots, have not 1. Provoked VTE or temporary risk fac- VTE and thrombophilia. Most experts

been studied in pregnant patients. Al- tors. It is unclear whether women with a agree that the management of pregnant

though there are compelling data from history of provoked VTE or temporary women with prior VTE and an acquired

both meta-analyses and several placebo- risk factors, such as a bone fracture or a or inherited thrombophilia requires

controlled, double-blind randomized tri- prolonged period of immobility, are at some sort of thromboprophylaxis in the

als demonstrating that there is no signifi- increased risk of VTE during pregnancy. antepartum and postpartum peri-

cant increase in major bleeding from They may be at lower risk than women ods.43,126-128 Although not prospectively

thromboprophylactic regimens of UFH or with a history of idiopathic VTE but at evaluated in a clinical trial, the intensity

LMWHs, there is a significant increase in higher risk than patients with no history of thromboprophylaxis should reflect

minor bleeding (66%) and impaired sur- of any VTE.52 However, as a conse- the relative risk conferred by having that

gical hemostasis observed with these quence of this theoretical increased risk thrombophilia. Most authors recom-

drugs.122 Not only is there a lack of data over the general obstetric population, it mend full anticoagulation using aspirin

regarding the efficacy of thromboprophy- is reasonable to counsel the patient ac- and heparin in women with a prior VTE

laxis in pregnancy and the potential for cordingly. At present, the need for either and antiphospholipid syndrome. In

increased morbidity, but concern about antepartum or postpartum thrombo- women with low-risk thrombophilias,

increased costs associated with thrombo- prophylaxis is unsettled, and clinicians such as hyperhomocysteinemia or factor

prophylaxis during cesarean delivery also are forced to manage cases on an individ- V Leiden/prothrombin G202010A het-

contributes to the lack of prophylaxis. ual basis. erozygosity, prophylactic doses of UFH

Until a prospective randomized trial of ad- 2. Idiopathic VTE. Few data are avail- or LMWH are probably sufficient. In

equate sample size is conducted that ad- able on the management of pregnant pregnant women with high-risk throm-

dresses this question, routine pharmaco- women who have a history of idiopathic bophilias, such as AT-III deficiency, ho-

logic thromboprophylaxis during cesarean VTE prior to the current pregnancy. mozygotes for either factor V Leiden or

delivery with UFH or LMWH cannot be These patients are likely to be at higher the G20210A mutation, or compound

recommended. However, such a trial is risk of VTE compared with individuals heterozygotes for factor V Leiden and

unlikely given the low VTE incidence rates without a history.46 One of the difficul- prothrombin G20210A mutations, ad-

and cost concerns. Because intermittent ties faced by physicians in counseling justed-dose UFH or LMWH to achieve a

pneumatic compression may be as effec- such patients lies in weighing the risks of target aPTT (2-2.5 control) or anti-Xa

tive as UFH or LMWH, and does not in- treatment with the risk of developing a level (0.5-1.0) should be recommended.

troduce risk to the patient,123 in the opin- thrombus. Prophylactic anticoagulation These relative risks and the recom-

457.e10 American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology NOVEMBER 2007

www.AJOG.org Obstetrics Review

mended intensity of prophylaxis are

summarized in Table 7.56,129,130 TABLE 7

Relative risk of recurrent VTE in pregnancy56,129,130

C ONSENSUS P ANEL Disorder Risk of VTE Prophylaxis intensity

R ECOMMENDATIONS FOR Factor V Leiden heterozygote 3- to 9-fold Low-dose prophylaxis

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

M ANAGING P ATIENTS W ITH Factor V Leiden homozygote 49- to 80-fold Adjusted-dose therapy

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

P RIOR VTE Prothrombin G20210A heterozygote 2- to 9-fold Low-dose prophylaxis

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

● In patients with a history of idiopathic Prothrombin G20210A homozygote 16-fold Adjusted-dose therapy

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

VTE, prophylaxis with LMWH or Antithrombin III deficiency 25- to 50-fold Adjusted-dose therapy

UFH may be considered antepartum ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Protein C deficiency 3- to 15-fold Low-dose prophylaxis

and for 6 weeks postpartum.46 (Level ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

IIIC) Protein S deficiency 2-fold Low-dose prophylaxis

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

● In patients with a history of 2 or more Hyperhomocysteinemia 2.5- to 4-fold Low-dose prophylaxis

..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

VTE episodes, antenatal and postpar- Antiphospholipid antibodies 5.3-fold Adjusted-dose therapy

tum prophylaxis with LMWH and ..............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Compound heterozygote of Factor V Leiden 150-fold Adjusted-dose therapy

UFH should be used.124,125 (Level and Prothrombin G20210A

IIIC)

● Patients with a history of VTE and

thrombophilia should receive prophy-

laxis with LMWH or UFH. Prophy- history, asymptomatic pregnant patients C ONSENSUS P ANEL

laxis intensity should be tailored to the with AT-III deficiency or those who are R ECOMMENDATIONS FOR

risk conferred by the thrombo- homozygotes or compound heterozy- M ANAGING P ATIENTS W ITH N O

philia (Table 756,129,130).43,126-128 gotes for the factor V Leiden or pro- P RIOR VTE OR APO B UT W ITH

(Level II-3C) thrombin G20210A mutations are at T HROMBOPHILIA

● Patients with a history of VTE on pre- very high risk for maternal thromboem-

gestational full anticoagulation should bolic disorders and require UFH or ● There is insufficient evidence to rec-

be maintained on full anticoagulation LMWH throughout pregnancy.43 With ommend anticoagulant drug treat-

during pregnancy. (Level IIIC) the exception of the above, there does ment during pregnancy in asymptom-

not appear to be any justification for an- atic women with no prior VTE or

H OW TO M ANAGE P ATIENTS tenatal treatment with UFH or LMWH APO. Some such patients will have ad-

W ITH N O P RIOR VTE OR in asymptomatic patients incidentally ditional risk factors that may lead the

A DVERSE P REGNANCY found to have an inherited thrombo- clinician to treat.132 (Level IIIC)

O UTCOMES B UT W ITH philia and no history of prior VTE or ● Asymptomatic women with AT defi-

T HROMBOPHILIA characteristic adverse pregnancy out- ciency or who are homozygotes or

Retrospective data have been used to comes.7,43,124 Short-term thrombopro- compound heterozygotes for the fac-

suggest that previously asymptomatic phylaxis with UFH or LMWH might be

tor V Leiden and prothrombin

women with an inherited thrombophilia considered in pregnant women with

G20210A mutations require thera-

are at increased risk of VTE and a poten- thrombophilia and no history of VTE or

peutic UFH or LMWH throughout

tially poor obstetric outcome.131 How- adverse pregnancy outcomes when other

pregnancy.43 Asymptomatic patients

ever, the only prospective study involv- risk factors are also present, such as mul-

incidentally found to have other in-

ing previously asymptomatic women tiple family members with VTE or med-

herited thrombophilia and no prior

who tested positive for factor V Leiden ical complications known to be associ-

ated with VTE. VTE or APO do not require UFH or

revealed no higher rates of VTE, pre-

Current guidelines are based on rec- LMWH.5,43,124 (Level II-2B)

eclampsia, or fetal death in comparison

ommendations by the American College ● For patients being treated with LMWH,

with those women who tested negative

for this mutation.132 Also, it is likely that of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and are if an antifactor-Xa level is evaluated, the

the level of risk varies according to the grade 1C (equivalent to level II-2 in these target peak range (drawn 3-4 hours after

type of thrombophilia and the presence guidelines), derived mainly from obser- subcutaneous administration) is 0.2-0.4