Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Hina AW Eporter: April 2011 Volume 7, Issue 1 China Committee Leadership

Hochgeladen von

Malcolm RiddellOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Hina AW Eporter: April 2011 Volume 7, Issue 1 China Committee Leadership

Hochgeladen von

Malcolm RiddellCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CHINA LAW REPORTER

中国法律报道

April 2011

Volume 7, Issue 1

China Committee REPORTING ON DEVELOPMENTS IN THE FOUR LEGAL SYSTEMS OF

Leadership GREATER CHINA

Co-Chairs

Adam F. Bobrow

abobrow@doc.gov

Russell K.L. Leu Happy Year of the Rabbit!

rklleu@yahoo.com

Welcome to the 2011 Spring edition of the China Law Reporter. The

Vice Chairs editorial team has done another excellent job of updating us on the latest

Paul B. Edelberg legal developments in China. As Co-Chairs, we truly appreciate the

pedelberg@foxrothschild.com submissions of our authors and the hard work put in by our editorial team.

Justin Evans

juwevans@alumni.iu The editorial board invites submission of articles for its next issue that fall

Robin Kaptzan within the mission of the China Law Reporter. Inquiries and submissions

kaptzan.r@grandall.com.cn can be made to Senior Co-Editors Russell Leu (rklleu@yahoo.com) or

Adam Li Paul Edelberg (PEdelberg@foxrothschild.com ).

liqi@junhe.com

Malcolm McNeil This issue’s articles include coverage of the much-discussed new national

MMcNeil@foxrothschild.com security review process for foreign investments. Coupled with the

Susan Ning coverage of new structures for private equity investors seeking to develop

Susan.ning@kingandwood.com

funds in China, we see a changing trend on the type of foreign investment

Richard Lawton Thurston

dick_thurston@tsmc.com that will be favored in coming years. With a new emphasis on growth in

Stephen Vogel seven strategic industries also highlighted in the 12th Five Year Plan

svogel@fulbright.com adopted last month during the annual session of the National People’s

Adria E. Warren Congress, we anticipate that foreign-invested enterprises will continue to

AWarren@foley.com have to demonstrate the ways they contribute to Chinese economic

growth.

Newsletter Editors

Russell K.L. Leu Another full-length article in this issue provide us with a better sense of

(Senior Editor)

leu@taftlaw.com

how the global economic downturn is playing out in cases in Chinese

Paul B. Edelberg courts related to commercial transactions. In recent years, Chinese courts

(Senior Editor) have followed a Supreme Court Judicial Interpretation allowing parties to

pedelberg@foxrothschild.com seek court relief to modify or rescind a contract if there was shown a

Jamilia Wang “fundamental changes of circumstances.” Most recently, Chinese courts

jamiliaw@gmail.com have displayed a more cautious attitude, distinguishing “fundamental

changes of circumstances” from normal commercial risks. The specific

Editorial Staff cases covered in this article will be of great use to practitioners working in

Kevin Blood China or with clients with significant Chinese business.

Kevin.blood@asu.edu

Alice Leung

aliceleung_ca@yahoo.ca As we welcome you to the Spring Meeting of the International Law

Section of the ABA with this issue of the China Law Reporter, we hope

you will enjoy the China Committee sponsored and co-sponsored

programs on the agenda. These programs should serve to remind

members that there are many ways to get involved and develop as a leader

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

CHINA LAW REPORTER

中国法律报道

April 2011

Volume 7, Issue 1

China Committee REPORTING ON DEVELOPMENTS IN THE FOUR LEGAL SYSTEMS OF

Leadership GREATER CHINA

Co-Chairs

Adam F. Bobrow

abobrow@doc.gov Co-Chairs Message, continued

Russell K.L. Leu

rklleu@yahoo.com within the Section and especially within the Committee. As the Co-

Chairs, we will always be happy to provide advice and support for any

Vice Chairs programming, publication and policy initiatives proposed by our

Paul B. Edelberg Committee members. We have active chapters in both Shanghai and

pedelberg@foxrothschild.com Beijing and the Section can support a wide variety of activities for

Justin Evans

juwevans@alumni.iu Committee members. Please do not hesitate to reach out to either of us.

Robin Kaptzan (Our email addresses are below.) And if you need guidance on what

kaptzan.r@grandall.com.cn programs are available, please feel free to simply express interest—we’ll

Adam Li help you get started!

liqi@junhe.com

Malcolm McNeil All the best,

MMcNeil@foxrothschild.com

Susan Ning Adam Bobrow, Co-Chair (abobrow@doc.gov)

Susan.ning@kingandwood.com

Russell Leu, Co-Chair (rkleu@yahoo.com)

Richard Lawton Thurston

dick_thurston@tsmc.com

Stephen Vogel Adam Bobrow is the Senior Advisor for China Policy Coordination for

svogel@fulbright.com the Secretary of Commerce.

Adria E. Warren

AWarren@foley.com Russell Leu is an attorney with the Beijing office of the law firm Taft,

Stettinius & Hollister LLP.

Newsletter Editors

Russell K.L. Leu

(Senior Editor)

leu@taftlaw.com

Paul B. Edelberg

(Senior Editor)

pedelberg@foxrothschild.com

Jamilia Wang

jamiliaw@gmail.com

Editorial Staff

Kevin Blood

Kevin.blood@asu.edu

Alice Leung

aliceleung_ca@yahoo.ca

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter

Page 3 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

CHINA ADOPTS PROCESS FOR NATIONAL SECURITY

REVIEWS OF MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS INVOLVING

FOREIGN INVESTORS

By Libin Zhang and Casey Rubinoff

When China’s former leader Deng Xiaoping gave permission to Dr. Armand Hammer to

fly his private plane into China in 1981 for negotiation of China’s first joint venture for a

coal mine in Antaibo, little did China’s government at the time think about national

security concerns involving foreign investment. Since then, China has become a focal

point for foreign investors worldwide. In 2010, China received $105.7 billion in foreign

direct investment (FDI). The World Bank reported that roughly 20% of all FDI going to

developing countries from 2000-2011 went to China.1 However, over the last five years

the Chinese government has created new policies and governmental bodies to safeguard

the domestic economy and national security in the face of the vast influx of investments

and mergers and acquisitions.

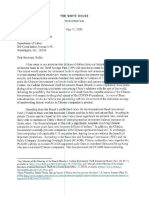

The most recent development is the State Council’s February 12, 2011 promulgation of

the Notice of the General Office of the State Council on Establishing a Security Review

Mechanism for Mergers and Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors

(Notice), which came into effect on March 5, 2011. The Notice sets forth a national

security review system for investments in and acquisitions of domestic companies by

foreign investors that may raise national security concerns. The security review process

under the Notice is intended by the Chinese government to be a regulatory review process

regulating M&As by foreign investors in China.

As a supplement to the Notice, on March 4, 2011, the Ministry of Commerce

(MOFCOM) issued the Tentative Provisions of the Ministry of Commerce on Issues

Related to the Implementation of the Security Review Mechanism for Mergers &

Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors (the “Provisions”). The

Provisions call for submission of opinions and comments by the public to MOFCOM

from the date of publication through April 10, 2011. The Provisions set forth further

details and regulations for implementation of the security review process provisionally

until August 31, 2011.

1

http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/EXTCHINESEHOME/EXTCOUNTRIESCHINESE/EX

TEAPINCHINESE/EXTEAPCHINAINCHINESE/0,,contentMDK:22648814~menuPK:3885991~pagePK:

2865066~piPK:2865079~theSitePK:3885742,00.html

The Section of International Law: Your Gateway to International Practice

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

国际法分部:你的跨国执业之门

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 4 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

Background

The national security review is not necessarily ‘new’ as China already has review

mechanisms in place to block deals that are not in line with its national strategy and the

establishment of a national security review has long been anticipated. In August 2006

MOFCOM along with several other agencies published the Rules on Mergers and

Acquisitions of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors, which, for the first time,

required notification and review of deals that had the potential to impact the country’s

economic stability. Then, in August 2008 China’s Anti-Monopoly Law (the “AML”)

went into effect, requiring further review of the impact of acquisitions of domestic

companies. Article 31 of the AML states:

Where a foreign investor participates in concentration of business operators

through a merger or acquisition of a domestic enterprise or any other method and

national security is involved, a state security review shall be conducted in

accordance with relevant state provisions in addition to the examination of the

concentration of business operators conducted in accordance herewith.

In April 2010, the PRC State Council issued Several Opinions on Further Improving the

Work of Utilizing Foreign Investment (“Opinions”). The Opinions advised the

government to accelerate the creation of a national security review mechanism for M&A

activity by foreign investors. The February 3, 2011 issuance of the Notice formally

established this review process and the scope of the review, which is independent from

the AML review process. Obviously, the national security review process is simply a

more codified way of conducting the reviews with the specific aim of protecting national

security. It should also be noted that a security review of mergers and acquisitions of

domestic financial institutions will be provided separately at a later date.

Affected Sectors

The Notice provides that mergers and acquisitions related to any military enterprise (1-3

below) and investments in the business sectors identified and outlined in number 4 below

where a foreign investor obtains “actual control” (to be discussed later), are subject to the

security review:

1. military and military supporting enterprises;

2. enterprises in the vicinity of major and sensitive military facilities;

3. other entities associated with national defense and security; and

4. domestic enterprises engaged in sectors related to national security such

as:

a) important agricultural products;

b) important energy and resources;

c) important infrastructure;

d) important transportation services;

e) key technologies; and

f) major equipment manufacturers.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 5 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The Notice does not define the words ‘important,’ ‘key,’ or ‘major’ as used in the Notice.

Additionally, it is interesting to note that some of the sectors listed above that will be

under particular scrutiny for M&A activity such as energy and agriculture, are areas in

which foreign investment had previously been encouraged under China’s Foreign

Investment Industrial Guidance Catalogue (the “Catalogue”). The Catalogue, as recently

amended by the PRC’s National Development and Reform Commission (the “NDRC”) in

2007, categorizes various industry sectors as ‘encouraged,’ ‘restricted,’ or ‘prohibited’

for foreign investment and is updated periodically by MOFCOM and the NDRC. Several

of these sectors fall under the nine “pillar industries” announced in December 2006 as

sectors in which State-owned enterprises should play leading roles.

Actual Control

Under the Notice, foreign investment in the sectors mentioned above in which a foreign

investor obtains actual control of a Chinese company is subject to the national security

review. The concept of ‘actual control’ is a broad one, encompassing not only

investments where foreign investors obtain a majority of equity interest, but also those in

which a foreign investor is able to exercise ‘material influence’ or control over company

decisions, although it may obtain only a minority interest in the target. As defined by the

Notice, actual control occurs when ‘a foreign investor becomes a holding shareholder of

or has actual control of a domestic enterprise after the merger and acquisition.’ This

includes the following circumstances:

1. The foreign investor, holding parent company or held subsidiary obtain

more than 50% of total shares after the merger or acquisition.

2. After the merger or acquisition two or more foreign investors aggregately

hold more than 50% of total shares.

3. Although the equity held by a foreign investor is less than 50% after the

merger or acquisition, the voting rights represented by the equity held by

them is sufficient to substantially influence the resolutions of the

shareholders meeting, shareholders assembly or the board of directors.

4. Any other circumstance in which actual control of a domestic enterprise’s

operational decisions, finances, personnel, technology, or other matters is

transferred to the foreign investor.

Application and Review Process

If a target company’s scope of business falls under one of the categories described in the

Notice, the foreign investor shall submit an application for security review with

MOFCOM. According to the Provisions, if more than one foreign investor is involved,

the foreign investors can either jointly submit an application or elect one of the parties to

submit the application on behalf of them all. The wording of the Provisions suggests that

it shall be the foreign investor and not the Chinese target who is responsible for

submitting the application and relevant materials. If a foreign investor does not submit an

application, but the local government finds that the transaction falls under the scope of

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 6 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

the security review, the local government will not accept the application for the M&A

transaction and will instead request that the parities submit a security review application

to MOFCOM.

Moreover, any relevant department under the State Council, any national industry

association, any enterprise in the same industry, or any upstream or downstream

enterprise may propose to MOFCOM to conduct the security review on a particular

transaction by submitting relevant information on the transaction and its supposed impact

on national security. This creates the potential for competitors of the target company to

ask MOFCOM to conduct security reviews on transactions that they oppose.

Article 3 of the Provisions stipulates that applicants may consult with MOFCOM prior to

filing an application regarding procedural issues. However, neither the Notice nor the

Provisions allows for lobbying during the review process or the possibility of appealing a

decision.

For filing for the national security review, the applicant should prepare, inter alia, an

application report and description of the transaction signed by the legal representative or

authorized representative of the applicant, the background information on the foreign

investor and its affiliated enterprises (including its actual control or parties acting in

concert), and statement on relationship with the government of relevant countries and the

background information on the target domestic enterprise including Articles of

Association, business license (copy), audited financial statements for the previous year,

structural chart before and after the M&A, company’s subsidiaries and relevant business

licenses (copy).

The applicant should also submit the Articles of Association, JV Contract or Partnership

Agreement of the foreign-invested enterprise that is planned to be established after the

M&A transaction and a list of proposed senior executives. In the case of an M&A

transaction involving equity transactions, the applicant shall submit the share transfer

agreement or subscription agreement, the relevant shareholder resolution of the target

domestic enterprise, and the relevant asset assessment report. In the case of an M&A

transaction involving assets transfer the applicant shall submit the resolution on the sale

of assets approved by the owner approving the asset sale, the asset purchase agreement

(including the checklist and status of assets to be purchased), a statement on the

information of all concerned parties of the agreement and a corresponding asset

evaluation report.

Finally, the application should also include a statement of the impact of voting rights

enjoyed by foreign investors to the resolution of the shareholders’ meeting and the

resolution of the board of directors, or to the enforcement of partnership affairs, statement

on other issues that may result in transfer of actual controlling power in relation to

decision-making, finance, human resources, technologies or other aspects to foreign

investor or its domestic or foreign affiliated enterprises, or agreement or documents

related to the aforementioned circumstances. MOFCOM has discretion to request

additional documents for filing.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 7 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

After a foreign investor who intends to acquire a domestic company files an application

with MOFCOM, MOFCOM will analyze the transaction for its potential impact on

national defense and security, economy stability, basic social order, and the domestic

capability to research and develop key technologies related to national security. Should

the transaction fall within one of the identified business sectors of the security review,

MOFCOM, within 5 working days, will request a security review by the Joint

Committee, which consists of the State Council, NDRC, and MOFCOM along with

relevant departments from the sector and industry under review.

The review process begins with a general review of the transaction, which can last up to

30 working days. If a transaction does not obtain approval after the general review, it

will then be subject to a special review, which can last up to another 60 working days.

After the review, the Committee can approve or terminate the transaction or may approve

of the transaction subject to certain conditions to address the national security concerns.

Transactions can also be modified by the parties during the security review process and

resubmitted to the Committee.

Necessity, Ambiguity and Uncertainty

What lies behind the legislation is that China’s government needs to constrain foreign

investment and protect and boost domestic industries. As it is for every country, national

security is a real issue for China. After decades of encouraging investment, the country

has a legitimate concern for national and economic safety and arguably needed to

implement a control measure.

However, some have voiced their disapproval of the mechanism, claiming that it has been

created simply to give the government the power to block more deals by foreign investors

in order to protect domestic industries. Some commentators viewed the establishment of

the national security review as a way for China to ‘turn the tables’ on those nations that

have previously blocked Chinese investment and serve as an economic tool of

reciprocity.

Fairly speaking, China is not the first, nor will it be the last, country to implement a

national security review mechanism. The U.S., Germany, Russia, Canada and Australia,

among others, have each either considered or already implemented a foreign investment

review process based on national security risks. Several of these countries have even

used their own security review mechanisms to block investments and acquisitions by

Chinese companies. Some observers said that the review has been established to ‘get

back’ at these countries that have hindered Chinese business and investment abroad.

They are concerned that China’s security review mechanism may go beyond the ‘typical’

security review mechanisms of other countries by creating another level of bureaucratic

control and encompassing matters outside of the scope of national security such as

economic and social stability.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 8 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The extent to which this mechanism has the potential to be abused by the government to

block deals in the name of national security remains to be seen. In the long run, China,

while moving in its uphill rise in the process of industrialization and globalization, cannot

afford to antagonize foreign investors and should still actively encourage foreign

investment. While there is a risk for abuse of this new power, history shows that the

Chinese government has been conservative in exercising its ability to block deals.

According to a US-China Business Council report in 2010, since the AML’s inception,

MOFCOM has reviewed over 140 M&A cases and approved 95% of those cases without

conditions (seven cases with conditions).2 MOFCOM has only rejected one case, Coca-

Cola’s proposed acquisition of Huiyuan Juice Company.3 However, these numbers do not

reflect those that felt inhibited from going through with an M&A transaction because of

China’s AML review.

National security reviews have been increasingly politicized in many countries and used

as tools of protectionism, perhaps in the face of the global economic recession. However,

countries must keep in mind that protectionism is a losing game when security reviews

move away from actual security concerns and have the potential to be mutually

economically destructive to the concerned parties.

Indeed, many countries’ legislations on national security reviews have intentionally left

the term ‘national security’ undefined and the language of the legislations has typically

been vague and general. Indeed, this is also the criticism of some commentators on the

Notice. The lack of definitions has left many fearful that the government will use its

discretion to define the scope of the terms set out in the Notice in their broadest sense.

Part of the problem in the vague language is that foreign investors who plan to comply

with the review process may be unaware whether the target business falls under a ‘key’

sector because the Notice does not list specific sub-sectors. Additionally, the ambiguity

of terms such as ‘social stability’ and ‘actual control’ means that what constitutes a risk

to national security or a controlling investor will be left to the judgment of MOFCOM

and the Joint Committee during review.

Chinese legislations have occasionally been known to be vague and general due to the

need to have provisional legislation for experimentation and thus leave room to provide

detailed rules in later notices and regulations. It is also possible that the language of the

Notice was intentionally left vague and undefined by the regulators so that transactions

will be judged on a case-by-case basis to stay in line with national plans; a tactic that

many countries use to their advantage when adopting legislations relating to national

security reviews of foreign investment.

Advice to Foreign Investors

In light of the above, we think foreign investors should consider the following before

acquiring any PRC domestic companies. First, foreign investors should keep a close eye

on development of the process of the review mechanism, particularly during the test

2

http://www.uschina.org/members/publications/cmi/2010/december/22/04.html

3

Disclosure: A partner of Broad & Bright represented Coca-Cola in this case.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 9 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

period of the Provisions. Second, foreign investors planning M&A in China should

thoroughly assess the effect that the national security review legislation will have on their

transactions and whether they will need to file for review. It is uncertain how things will

play out in reality of the implementation of the legislation and certainly many lessons will

be learned by both investors and the government. What is certain is that the legislation

regarding national security review will develop further and become more sophisticated

over time, whether for better or for worse.

Libin Zhang is a partner at Broad & Bright in Beijing and can be reached at Tel: 86-10-

85131818 or by email: Libin_zhang@broadbright.com

Casey Rubinoff is a paralegal at Broad & Bright and can be reached by email:

casey_rubin@broadbright.com

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 10 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

U.S. FUNDS LOOK TO RMB FUND

STRUCTURES IN CHINA

By Paul B. Edelberg

Until recently, U.S. private equity funds were limited under Chinese law to investing in

China through offshore vehicles. They could opt to invest through a wholly owned

subsidiary in China (commonly called a “WFOE”) or by creating a Sino-foreign joint

venture company with the target. The establishment of a foreign-invested WFOE or

joint venture company has required regulatory approval from the Ministry of Commerce

(known as “MOC”) and the State Administration of Industry and Commerce (“SAIC”) or

their respective provincial or local offices, and in some cases from other government

agencies, through a lengthy and laborious process. Among the various requirements are

minimum registered capital requirements established by these government agencies.

Typically, 15% of the registered capital has to be transferred to RMB accounts in China

within 90 days after approval, with the balance being due typically within two years.

This requires careful planning for funding investments and keeping capital at work. In

addition, foreign investors under this process have been subject to the Catalogue of

Industrial Guidance for Foreign Investment (the “FIE Industry Guidelines”)4, under

which industries are classified as encouraged, restricted or prohibited for foreign

investment (or, if not listed, presumed to be permitted) for acquisition by foreign-invested

entities. In most cases, separate approvals are needed for each investment. If not

properly structured and approved, foreign funds cannot be converted into RMB.

In 2003 the Chinese Government authorized private equity investments through an

onshore vehicle called a foreign-invested venture capital investment enterprise (a

“FIVCE”) as discussed below, but this structure has been subject to many of the above

requirements in addition to others. While a number of foreign PE funds have

successfully invested in China and have followed this difficult process, the obstacles have

hindered foreign PE investment in China.

In response to these hurdles, the Chinese Government over the last several years has

implemented regulations and made pronouncements to promote alternative onshore

structures for foreign private equity investment, called “RMB funds”. This article will

discuss recent legal developments and will explore which structures U.S. private equity

firms might consider using in structuring their funds in China.

4

Catalogue of Industrial Guidance for Foreign Investment, issued by the National Development and

Reform Commission and the Ministry of Commerce (Nov. 7, 2007, effective Dec. 1, 2007).

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 11 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

Recent Developments

The domestic PE industry in China has grown rapidly over the last several years. With

the increase of domestic wealth in China, together with excess government funds,

Chinese PE funds are able to raise capital domestically with relative ease. It has been

difficult for foreign PE funds to tap Chinese wealth, since regulations issued in 2006 have

made it difficult to restructure Chinese domestic companies as Chinese-owned offshore

companies or to move Chinese capital offshore. According to Zero2IPO Research Centre,

in 2009, for the first time more capital was raised for investment in China by domestic PE

firms than by foreign PE firms.5

Foreign PE funds are competing against domestic funds for deal flow, and there are more

funds available for investment than there are mature targets. Domestic PE funds do not

have to undergo the approval process that foreign PE funds do, which gives them a

distinct advantage. In addition, the national, provincial and municipal governments and

other state-owned entities have all set up sovereign wealth funds to invest into certain

geographic areas or certain industries.

In 2010 China’s Central Government announced that it would encourage the flow of

foreign capital into China, particularly in the high technology, high-end manufacturing,

renewable and clean energy and environmental industries. In Several Opinions of the

State Council on Utilizing Foreign Capital, Opinion No. 9, issued by the State Council

on April 6, 20106, the State Council declared a national policy towards easing restrictions

and facilitating the growth of foreign investment through foreign-invested PE funds and

directed the various government agencies to issue regulations implementing this policy.

On June 10, 2010, MOC issued its Circular on Delegating Approval Authority over

Foreign-Invested Enterprises7 that delegated approval authority for investments under

US$300 million by FIVCEs to provincial and local MOC authorities and shortened the

approval times for these investments.

On November 25, 2009, the State Council announced the Administrative Measures for

the Establishment of Partnership Enterprises by Foreign Enterprises and Individuals,

effective March 1, 2010 (the “Foreign Partnership Measures”)8. These Measures for the

first time allow foreign investors to establish foreign-invested limited partnerships

(known as “FILPs”). In essence, the authorization for FILPs enables foreign PE firms to

create onshore limited partnership funds.

5

http://www.allbusiness.com/banking-finance-markets-investing-funds/13773433-1.html.

6

Several Opinions of the State Council on Further Utilizing Foreign Capital, Guo Fa [2010] No. 9, issued

by the State Council (April 6, 2010) (“Opinion No. 9”).

7

Circular of the Ministry of Commerce on Delegating Approval Authority over Foreign Investment to

Local Counterparts, Shang Zi Fa [2010] No. 209, issued by the Ministry of Commerce (June 10, 2010),

Art. 4.

8

Administrative Measures for the Establishment of Partnership Enterprises by Foreign Enterprises and

Individuals, Order of State Council (Guo Wu Yuan Ling) [2010] No. 567, issued by the State Council

(Nov. 25, 2009) (“Foreign Partnership Measures”).

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 12 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

Another development of note is the encouragement of foreign private equity in certain

cities, particularly Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin. Tianjin, which has been designated by

the Central Government for private equity development, is competing with the other two

well-known financial centers for private equity growth. Because of the lack of clarity at

this early stage in Chinese private equity law, these cities have issued regulations to

authorize certain PE activity not yet specifically authorized under national law. These

cities have also offered certain tax incentives to encourage foreign-invested PE entities to

form and register in those cities.

The use of an offshore structure is still a viable option and may still be preferable in

certain instances. However, these recent developments have opened the way for foreign

private equity firms to create onshore RMB funds, which many believe will be the

preferred path for foreign private equity firms seeking to be serious players in the

Chinese market.

Types of Onshore Fund Entities

The historical onshore form used by foreign private equity firms has been the FIVCE.

However, recent developments have opened the possibility of other onshore structures.

FIVCE

A FIVCE may be formed with a Chinese partner as a legal person, such as a Sino-joint

venture company (also known as an equity joint venture), or as a non-legal person, such

as a contractual joint venture.9 The minimum capital requirement is US$5 million if an

equity joint venture and US$10 million if a contractual joint venture.10 At least one

investor must invest at least 30% of the registered capital.11 15% of the registered capital

must be paid within 90 days, and the balance must be paid within 5 years.12 Both US

dollars and RMB can be contributed.13 If a contractual joint venture, the parties will

benefit from pass-through tax treatment14; otherwise, an equity joint venture will be taxed

as an entity, and dividends received from the portfolio companies will under most

scenarios be subject to China’s Enterprise Income Tax Law at the entity level.

Management of a FIVCE may be delegated to a domestic management company, a

foreign-invested enterprise or an offshore entity.15

9

Administrative Regulations of Foreign-Funded Venture Capital Enterprises, issued by the Ministry of

Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the State

Administration for Industry and Commerce, State Administration of Taxation and SAFE [2003] No. 2, ,

(Jan.30, 2003, effective Mar. 1, 2003), Art. 4.

10

Id.,. Art. 6(2).

11

Id., Art. 7.

12

Id., Art.13(1).

13

Id., Art.6(2).

14

See Circular of the Ministry of Finance and the State Administration of Taxation on Issues Concerning

the Income Tax Levied on Partners of a Partnership Enterprise, Cai shui [2008] No. 159.

15

Id., Art.21.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 13 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

There are limitations to a FIVCE that make it disadvantageous for many foreign PE

firms. First, establishment of a FIVCE requires approval from central MOC if registered

capital (i.e., the amount to be contributed by both parties) is in excess of US$300

million.16 Second, each investment must be approved and is subject to the restrictions

and prohibitions in the FIE Industry Guidelines.17 Acquisitions of domestic targets for

transaction amounts of US$300 million (and in some cases, a lesser amount) require

central MOC approval, rather than local MOC approval, which will cause considerable

delay and uncertainty. Third, investments are limited to high technology and new

technology companies.18 Fourth, a FIVCE is not permitted to invest in listed

companies.19 Fifth, no debt is allowed to be used in acquisitions. Sixth, approval of the

Ministry of Science and Technology (“MOST”) is required to form a FIVCE because of

the limitations on the industries in which the fund can invest.20 Approvals in compliance

with China’s anti-monopoly law are also required where applicable.

With registered capital requirements and timing requirements for registered capital

infusions, maximizing fund deployment becomes complicated. Too many funds are

chasing too few deals, and transaction size in China is generally between US$50 million

to US$200 million. If the FIVCE’s registered capital is too high, the FIVCE may not be

able to timely deploy its assets effectively. One remedy is to set up a series of funds

seriatim, each no greater than the amount needed for two or three transactions. Another

problem of the capital requirements is the length of time for investment approvals, which

puts the FIVCE at a timing disadvantage to domestic RMB funds, which do not need

similar approval.

FILP

The Foreign Partnership Measures became effective as of March 1, 2010.21 Those

measures permit foreign entities and individuals to form a general or limited partnership

under Chinese partnership law, as modified by the Foreign Partnership Measures. The

approving authority is the local SAIC office, rather than MOC or its local offices,

although SAIC is required to notify the local MOC office of a FILP registration.22

Foreign entities with advanced technology business or with management expertise that

form FILPs to boost the modern service industry in China are viewed favorably under the

Foreign Partnership Measures.23 While the Foreign Partnership Measures state that the

foreign currency of the foreign partners shall be “freely exchanged”, it also states that

issues involving foreign currency, among others, shall “be handled according to relevant

laws, administrative regulations and relevant provisions of China.”24 Finally, the

16

Para. (16), Opinion No. 9, supra n. 3.

17

Id., Art.32(1).

18

Id., Art.3.

19

Id., Art.32(2).

20

Id., Art.8(3).

21

Foreign Partnership Measures, supra n. 5.

22

Id. Art. 5.

23

Id. Art. 3.

24

Id. Arts. 4 and 11.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 14 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

withdrawal of a foreign general or limited partner will necessitate applying to the local

SAIC office for modification of its registration.25

SAIC issued its Administrative Regulations on Registration of Foreign-Invested

Partnership Enterprises to implement the Foreign Partnership Measures, also effective

March 1, 2010.26 The regulations allow both general partnerships and limited

partnerships, the latter of which is relevant for private equity enterprises.27 A FILP is

limited to a maximum of 50 partners.28 While the Foreign Partnership Measures state

that MOC approval is not required, SAIC’s administrative regulations reserve the right to

require local MOC approval in specified instances. In addition, industry-specific

approvals and approvals of investments under the FIE Industry Guidelines may still be

required. 29 Approvals in compliance with China’s anti-monopoly law are also required

where applicable.

The two most obvious advantages of a FILP are the tax pass-through treatment and the

bypass of central or local MOC approval in most instances. The latter will expedite and

simplify the approval process. FILPs also are not subject to all of the restrictions of a

FIVCE, such as the limitation on types of investments. Moreover, there are no minimum

registered capital requirements, and no timing requirements for funding, thereby allowing

the funds to more easily raise capital on a committed basis and to better manage

deployment of assets. Another benefit is that FILPs are allowed to establish a branch

office without further approval (although registration of the branch is required). On the

other hand, there are limitations in using FILPs, partially due to regulatory limitations

and partially due to lack of clarity until further regulations are issued. With certain

exceptions, MOC or other government authorities must approve each investment. Each

investment is subject to the restrictions and prohibitions in the FIE Industry Guidelines.

FILPs are not eligible to access the public capital markets in China as an exit strategy.

Approvals in compliance with China’s anti-monopoly law are also required where

applicable.

A major obstacle is the lack of express authorization under national Chinese laws for an

onshore WFOE or joint venture as a general partner or management company of a FILP

formed for equity investments. In Circular 142 issued by the State Administration of

Foreign Exchange (“SAFE”) in 2008 to regulate the conversion of foreign funds of

foreign-invested enterprises (which include WFOEs and Sino-foreign joint ventures) into

RMB,30 SAFE took the position that it will prevent FIEs from converting foreign

currency into RMB if the purpose of the investment is not within the scope of the FIE’s

25

Id. Art. 8.

26

Administrative Regulations on Registration of Foreign-Invested Partnership Enterprises, issued by State

Administration for Industry and Commerce (Jan. 29, 2010).

27

Id. Art. 11.

28

Partnership Enterprise Law of the People’s Republic of China (Aug. 27, 2006, effective June 1, 2007),

Art. 61.

29

Foreign Partnership Measures, supra n. 5, Arts. 38 and 64.

30

Circular No. 142 of the State Administration for Foreign Exchange on Relevant Business Operations

Issues Concerning Improving the Administration of the Payment and Settlement of Foreign Exchange

Capital of Foreign-Funded Enterprises (Aug. 29, 2008).

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 15 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

business license. Despite the language regarding free convertibility in the Foreign

Partnership Measures, the conflicting language in the same Measures requiring

compliance with relevant foreign exchange laws and regulations has been interpreted to

restrict conversion pursuant to Circular 142. For a FILP to constitute a viable structure

for a U.S. private equity firm seeking to funnel its own capital or its own foreign

investors’ funds into its Chinese investments, this hurdle must be overcome.

Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin have adopted local rules to address some of the

impediments and uncertainties under the Foreign Partnership Measures and Circular 142.

Shanghai’s Pudong New Area reached an agreement with SAFE in 2009 to allow a

foreign general partner of a FEIMC to convert to RMB up to one percent of the total

capital raised by the fund. That rule was apparently superseded in January of this year

under the Implementation Measures on the Pilot Program of Foreign-Invested Equity

Investment Enterprises in Shanghai (the “Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures”).31

The local rules are discussed below.

FEIMC

Until recently, there were no relevant regulations authorizing or specifically regulating

foreign-invested management companies in China other than foreign-invested venture

capital management companies established to manage FIVCEs. While the Central

Government has yet to issue any such regulations, in the last few years Shanghai, Beijing

and Tianjin have issued local rules specifically authorizing and regulating foreign-

invested management companies, called “foreign-invested equity investment

management enterprises” (a “FEIMC”).32 All three cities permit FEIMCs to be formed as

equity joint ventures, WFOEs and FILPs. The FEIMC must be engaged in equity

investment management for private equity funds. The professional managers must satisfy

prescribed experience requirements. Each city offers tax benefits for forming a FEIMC

within its jurisdiction.

The Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures became effective January 23, 2011. The

Measures require minimum capital of US$2 million, of which 20% must be paid within

90 days and the balance within 2 years. A FEIMC may establish funds, manage

investments and provide private equity investment consulting services. The

promulgation of the local FEIMC rules is the first legal authorization for equity

investment management companies outside of the FIVCE context.

31

Implementation Measures on the Pilot Program of Foreign-Invested Equity Investment Enterprises in

Shanghai Hu Jin Rong Ban Tong [2010] No. 38 (Jan. 11, 2011, effective Feb. 10, 2011) ( “Shanghai Fund

Implementation Measures”).

32

See Circular on Printing and Distributing the Provisional Measures of Shanghai Municipality on the

Establishment of Foreign-Invested Equity Investment Management Enterprises in the Pudong New Area,

Pu Fu Zong Gai [2009] No. 2; Provisional Measures for the Establishment of Foreign-Invested Private

Equity Fund Management Enterprises in Beijing, Jing Jin Rong [2009] No. 163; Trial Implementation

Measures on Registration, Record Filing and Management of Equity Investment Funds and Equity

Investment Management Companies (Enterprises) in Tianjin (Nov. 5, 2009).

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 16 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures

The Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures are far reaching and extend beyond

authorizing FEIMCs, which had been previously authorized under the 2009 Pudong rules

mentioned above. The Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures also authorize

simplified procedures for establishing RMB funds in Shanghai, eliminate or minimize

disparities between foreign owned funds and domestic funds and permit conversion of

foreign currency investments by a foreign owned FEIMC and by certain qualifying

foreign limited partners.

A foreign-invested fund established under the Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures

(a “Shanghai FIE Fund”) must have minimum committed capital of US$15 million.33

Assuming the Shanghai FIE Fund is established as a FILP, only approval of the local

branch of SAIC is required; no MOC approval is required for its formation.34

There are two categories of Shanghai FIE Funds: those with only Chinese investors

(other than a foreign-owned FEIMC), and those with both Chinese and non-Chinese

investors. With respect to the first, the FEIMC may be partially or wholly owned by

foreign managers seeking to tap capital in China. The FEIMC may convert its foreign

currency into RMB to the extent of 5% of the committed capital of the Shanghai FIE

Fund.35 The fund will be treated the same as a domestic fund. It will not be subject to

the restrictions of the FIE Industry Guidelines, and its investments do not require

approval of MOC or its local offices.

With respect to Shanghai FIE Funds with both Chinese and non-Chinese investors, the

FEIMC is granted the same convertibility rights as a fund with only Chinese investors.

Certain large foreign investors are permitted to invest in foreign currency without

convertibility restrictions. These qualified limited partners must own assets of at least

US$500 million and must have managed at least US$1 billion in assets in the prior year.

These qualified limited partners must also satisfy requirements regarding corporate

governance procedures, experience levels and the absence of recent supervisory or legal

proceedings.36 Those limited partners who do not qualify will be subject to convertibility

restrictions and will be required to obtain the necessary SAFE approvals for each

investment.37 More importantly, Shanghai FIE Funds with both Chinese and non-

Chinese investors will be subject to the FIE Industry Guidelines and will be required to

obtain approval of MOC or its local offices for each investment.38

It is anticipated that Beijing and Tianjin will issue similar measures.

The Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures permit the formation of an onshore fund in

Shanghai managed by an onshore foreign-owned GP and manager. However, it remains

33

Shanghai Fund Implementation Measures, supra n. 28, Art. 14.

34

Id, Art.15 .

35

Id, Art. 24.

36

Id, Art.20.

37

Id, Art.5, 9, 14.

38

Id, Art.6.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 17 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

to be seen whether other municipalities will respect these new measures when the

Shanghai-based fund invests in those other municipalities.

RMB Fund without a FIVCE, a FEIMC or a Shanghai FIE Fund

Foreign private equity funds have tried various structures in the past to overcome the

legal restrictions of a FIVCE. Forming a standard foreign-invested enterprise without an

investment purpose within its business scope has not been viable since the issuance of

Circular 142. Others have formed foreign-invested enterprises or used offshore vehicles

to enter into contractual arrangements to manage domestic RMB funds. And others have

used shareholder notes in lieu of capital contributions to avoid being classified as foreign-

invested onshore funds. All of these hybrid methods risk acceptance by applicable

Chinese legal authorities.

Strategies for U.S. Private Equity Funds

Chinese regulation of foreign-invested private equity funds and management companies

is still in its infancy, and the strategies employed by U.S. private equity firms seeking to

enter the China market will need to be fluid to adjust to changing regulations.

Nonetheless, the PE firms will need to rely on the status of existing law and any

anticipated changes at the time it plans on entering China. To analyze which legal

structure to choose, the first step is to define the firm’s objectives.

If a U.S.-based PE firm merely wants to access Chinese capital and raise funds

domestically, the FEIMC and the Shanghai FIE Fund (or any equivalent fund formed

under similar rules of another municipality) provides a sound structure. In Shanghai at

least, the FEIMC (or if a Chinese partner is involved, the foreign partner) can invest and

convert into RMB up to 5% of the total committed amount of the fund it establishes. The

fund can be formed as a FILP, giving pass-through tax treatment. The fund can also be

used as a vehicle for LP investments by large qualifying institutional investors, although

each investment of the fund will then become subject to the FIE Industry Guidelines and

will require governmental approval.

If a PE firm is looking to infuse foreign capital into the Chinese market, a FIVCE

managed by a FEIMC may be the preferred structure. The FIVCE structure specifically

contemplates the conversion of foreign funds into RMB and is a viable structure for

foreign firms seeking to invest in China or to partner with a Chinese PE firm. The major

limitations for U.S. PE firms in a FIVCE are the requirements (1) that portfolio

investments be made in high technology and new technology industries, (2) that a FIVCE

with a legal person status cannot use the FILP as a vehicle, thereby denying investors of

pass-through tax treatment, (3) that a FIVCE must obtain MOC and MOST approval, (4)

that the investments must comply with the FIE Industry Guidelines, and (5) that the

FIVCE comply with timing requirements for pay-in of registered capital as they relate to

deployment of assets by the fund.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 18 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

For a U.S. PE firm seeking merely to co-invest its own funds alongside investments of its

Chinese partner, rather than creating a joint fund, it is still unclear whether the formation

of an onshore fund or FEIMC gives the U.S. PE firm any advantage. If the same FIE

restrictions apply to those onshore vehicles as they do to offshore funds, one approach is

to establish relationships with Chinese PE firms and co-invest on an ad hoc basis. The

Chinese PE firm must be willing to accept the restrictions of the FIE Industry Guidelines

and regulatory delays in executing on its potential targets.

It is recommended that legal counsel be consulted in choosing a structure and that advice

be obtained from qualified PRC counsel. Other factors may impact the general

conclusions stated in this article in any particular scenario. Moreover, the regulations

cited in this article have complexities that are beyond the scope of this article, with

numerous exceptions for particular situations, and other regulations may also apply to a

particular situation. Nor does this article discuss in depth the tax implications and exit

strategies available to U.S. private equity firms.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for general information purposes only and should not be construed as legal advice or legal

opinions on any specific facts or circumstances. An attorney-client relationship is not created by reading this article.

The author of this article is not admitted to practice law in China. While this presentation provides a general overview

of structuring options, nuances and changes in Chinese law may impact structuring options and strategies.

Paul B. Edelberg is a partner in the Stamford, Connecticut and New York, New York

offices of the law firm of Fox Rothschild LLP and can be reached by telephone at 203-

425-1521 and by email at pedelberg@foxrothschild.com.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter

Page 19 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

CHINESE COURTS ADOPT CAUTIOUS ATTITUDES

IN APPLYING “FUNDAMENTAL CHANGE IN

CIRCUMSTANCES” PROVISION IN

CONTRACTUAL DISPUTES ARISING FROM THE

GLOBAL ECONOMIC DOWNTURN.

By Susan Ning, Tao Huang and Yang Yang1

As was the case throughout the world, the global economic downturn beginning in 2008

caused many in the Chinese markets to face difficulties in fully performing executory

contacts formed prior to the crisis. Many parties to such contracts requested modification

or even rescission of these otherwise valid contracts under these changed circumstances.

In response to this trend, the Judicial Interpretation on Contract Law II2 was issued by

the Supreme People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China (hereinafter the “SPC”) to

further clarify certain legal rules under current Chinese Contract Law3. In particular,

Article 26, Chapter 4 of the Judicial Interpretation on Contract Law II (hereinafter

“Article 26” or the “Fundamental Change in Circumstances” provision) provides

guidance on a party’s right to modify or rescind a valid contract when a fundamental

change of circumstances occurs after contract formation. A fundamental change of

circumstances is differentiated from a force majeure event and does not cover changes

that may arise from normal commercial risks, or under which the purpose of the contract

would be frustrated or performance would result in extreme unfairness.

This article provides an overview of the prima facie elements of Article 26 and the

cautious attitude taken by the people’s courts in its application. In practice, Chinese

people’s courts will closely review the specific facts of each case in order to determine

whether the standards set by Article 26 are satisfied and then seek confirmation from

higher level judiciaries. Part I of this article is an introduction to the roles of the SPC,

Part II will provide an insight on the relevant provisions of Chinese contract law, to

which Article 26 is related; Part III is a detailed explanation of Article 26; Part IV is the

Conclusion.

I. Roles of the SPC

The Chinese legal system is based on civil law, meaning only laws and regulations

promulgated by the legislative bodies and their authorized government authorities are

binding. Court judgments outside the SPC only serve as interpretations of laws and do

not control in other cases.

1

Ms. Susan Ning and Mr. Tao Huang are Partners with King & Wood (PRC Lawyers), Ms. Yang Yang is

an Associate with King & Wood.

2

Judicial Interpretation of the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China II [“Judicial

Interpretation on Contract Law II”], Fashi [2009] 5, art. 26, chap.4 (promulgated by the Supreme Court of

People’s Republic of China on April 24, 2009, effective May 13th, 2009).

3 Contract Law of the People's Republic of China [“Chinese Contract Law”] (promulgated by the Nat’l

People’s Cong. March 15, 1999, effective October 1, 1999).

The Section of International Law: Your Gateway to International Practice

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

国际法分部:你的跨国执业之门

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 20 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The National People’s Congress (“NPC”) and its permanent committee, the Standing

Committee of the NPC are the primary legislative bodies that promulgate laws. The State

Council and its branches promulgate administrative regulations. Regulations

promulgated by the State Council, its ministries and organizations apply throughout the

nation, while regulations promulgated by local counterparts only apply to those local

administrative areas.

According to the Law of the Organization of the People’s Court of the People’s Republic

of China, people’s courts exercise nationwide judicial authority.4 The SPC is also

responsible for issuing judicial interpretations which provide guidance for all people’s

courts on the application of laws and regulations.5 Thus far, the SPC has issued two

judicial interpretations related to the Contract Law: (1) Judicial Interpretation on Contract

Law I;6and (2) Judicial Interpretation on Contract Law II.7 These interpretations provide

important guidance on the resolution of contract disputes.

II. Principles of Chinese Contract Law

Similar to most jurisdictions, under Chinese contract law, a valid contract is formed

through offer and acceptance. However, under certain circumstances, the contract itself

may be revocable8 or even void.9

Under PRC law, a contract may be revocable when it is unfair to a party at contract

inception, or the contract is made based upon significant misunderstandings or mistake

between the parties. A contract is void if a party has committed fraud, was coerced into

entering the contract, if the contract has an illegal subject or purpose, or if it contradicts

with mandatory laws or regulations.

The basic principle of Chinese contract law is that in valid contracts, a contractual party

must perform their respective obligations in accordance with the terms of the contract.

Neither party is allowed to unilaterally modify or rescind the contract;10 otherwise, it will

be liable for breach of contract. However, besides modification or rescission by mutual

agreement, Chinese contract law also provides some circumstances under which the

parties may be entitled to modify or rescind the otherwise valid agreement. These

circumstances include: (1) events of force majeure;11 (2) before the expiration of the

performance period, a party expresses explicitly or indicates through its acts, that it will

4

Law of the Organization of People’s Court of the People’s Republic of China [“Chinese Court Law”] art.

2-3, chap.1 (promulgated by the Nat’l People’s Cong. October 31, 2006 effective January 1, 1980).

5

Chinese Court Law, art.32, chap.2.

6

Judicial Interpretation of the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China I [“Judicial

Interpretation on Contract Law I”], (promulgated by the Supreme Court of People’s Republic of China on

December 29, 1999 effective December 29, 1999).

7

Supra note 2

8

Chinese Contract Law, art. 54, chap. 3.

9

Chinese Contract Law, art. 52, chap. 3.

10

Chinese Contract Law, art.8, chap. 1.

11

Chinese Contract Law, art. 117, chap. 7

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 21 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

not perform its principal debt obligations; (3) a party delays in performing its principal

debt obligations and fails, after being urged, to perform them within a reasonable time

period; (4) a party delays in performing its debt obligations or commits other acts in

breach of the contract so that the purpose of the contract is not able to be realized, and (5)

other circumstances provided by law.12

In short, if the parties desire to rescind a contract, they have three options: (1) mutually

agree to rescind the contact,(2) have provisions in the contact listing the events or

conditions which give rise to a rescission,13 or (3) rely on the above listed exceptions.14

For all three potential options to rescinding a contract, the legal procedures are the same.

First, the party requesting the rescission will serve notice upon the receiving party. If the

receiving party does not object, the contract will terminate. If the receiving party objects,

the requesting party must bring an action before the people’s court or an arbitration

commission subject to an arbitration agreement.15 The receiving/objecting party may

also file counterclaims to demand continued performance of the contract.16 The lawsuit

must be filed within a specific period as agreed by the two parties. If the two parties do

not agree on any specific period, the parties must file a lawsuit within 3 months of receipt

of the notice for rescinding the contract.17

III. Article 26 or the “Fundamental Change of Circumstances” Provision

The “fundamental change of circumstances” provision was not originally included in the

Contract Law, but was issued as a judicial interpretation during the recent global

economic downturn. The provision gives a contracting party the right to request

modification or rescission of a contract under “fundamental change of circumstances,”

but also sets up very strict conditions. Article 26 states:

“After a contract is legally formed, in view of objective circumstances not

anticipated by the parties when the contract was formed, not caused by

force majeure nor commercial risks, and significant changes occur so that

continuing the performance of the contact is unfair and inequitable to one

party or the objective of the contract cannot be fulfilled, then a party or both

parties may request the people's court to modify or rescind this contact.

12

Chinese Contract Law, art.94, chap.6.

13

Chinese Contract Law, sec.2, art. 93, chap. 6

14

Supra note 12.

The parties to a contract may rescind the contract under any of the following circumstances:

(1) The purpose of the contract is not able to be realized because of force majeure;

(2) One party to the contract expresses explicitly or indicates through its acts, before the expiry of the performance

period, that it will not perform the principal debt obligations;

(3) One party to the contract delays in performing the principal debt obligations and fails, after being urged, to perform

them within a reasonable time period;

(4) One party to the contract delays in performing the debt obligations or commits other acts in breach of the contract

so that the purpose of the contract is not able to be realized; or

(5) Other circumstances as stipulated by law.

15

Chinese Contract Law, art. 96, chap. 6.

16

Judicial Interpretation on Contract Law II, art. 24, chap. 4.

17

Id.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 22 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The people’s court shall abide by the principle of fairness and consider the

actual situations involved in this case before making a decision on

modifying or revoking the contract at issue.”

Accordingly, there are four elements that must be present in order to establish a prima

facie case so a request may be made to a court to modify or rescind a valid contract:

A. objective circumstances exist that were not anticipated by the parties when

the contract was formed;

B. the change of circumstances is not caused by force majeure;

C. the change of circumstances is not a result of a normal commercial risks;

and,

D. the continuing performance of the contact would be unfair and inequitable

to one party or the objective of the contract cannot be fulfilled.

In deciding whether to grant a request for modifying or revoking a contract, the people’s

courts will primarily consider (1) the principle of fairness and (2) the surrounding facts

involved in each individual case.

In addition, the SPC announced two additional policies after Article 26 which further

clarify the application of the Article: (1) Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the

Current Environment18 ; and (2) Announcement on Serving the State and Communist

Party by Correctly Applying Judicial Interpretation of the Application of Contract Law of

the People’s Republic of China II 19. In particular, the Guidance for Trials on Contract

Litigation in the Current Environment provides four policy objectives that we will

discuss further. These policies are very important to ensure fair and unified application

of Article 26.

A. Objective Circumstances Unanticipated by the Parties when the

Contract was formed.

The Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current Environment provides

standards for the interpretation of “unanticipated circumstances.”20 Standards are based

on: a reasonable person in common society standard, whether the level of risks is beyond

a reasonable person’s expectations, whether the risks can be avoided or controlled, and

whether transactions are of a high risk or high return nature. The people’s courts will

consider the circumstances involved in specific cases and make decisions on a case-by-

case basis.

18

Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current Situation [“Guidance on Contract Trials”]

(promulgated by the Supreme Court July 7, 2009, effective July 7, 2009).

19

Announcement on Serving the State and Communist Party by Correctly Applying Judicial Interpretation

of the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China II, (Fa [2009] 165) (Promulgated by the

Supreme Court.

20

Supra note 18.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 23 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

Some recent cases may provide insight into the meaning of “unanticipated objective

circumstances.” In April, the Beijing Municipal Government issued an announcement

that prohibited banks from issuing mortgage loans to home purchasers who already

owned two residential units. At the time this announcement was issued, many real estate

purchasers that already owned two or more units had entered into additional purchase

agreements. Therefore, many residential unit purchasers filed lawsuits with the people’s

courts claiming that due to this announcement, they could not obtain mortgage loans and

therefore could not afford to perform their end of the purchase agreements. In July, the

Beijing Haidian District Court announced the courts would recognize this development as

an “unanticipated objective circumstance.”

B. What is Force Majeure

Force majeure under Chinese Contract Law is defined as an extraordinary circumstance

that is unforeseeable, unavoidable and out of the control of any party.21 In practice, events

of force majeure mainly include natural disasters, wars, strikes, riots, civil commotions,

fires, explosions, sabotage, terrorism, or embargos. In 2003, the Chinese Supreme Court

issued an announcement that recognized “SARS” as an event of Force Majeure.

Article 26 requires that the objective circumstance unanticipated by the parties is not

caused by events of force majeure. However, Article 26 does not provide definitions for

the differences between force majeure and fundamental change of circumstances. From

the Beijing Haidian District Court’s decision referred to above, it seems that changes in

laws may also be recognized as a fundamental change in circumstances. Article 26 was

issued last year and more time is needed to fully understand the courts’ attitude in

differentiating between the two.

C. Difference between “Fundamental Change of Circumstances” and

“Commercial Risks”

Both Article 26 and the Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current

Environment stress a fundamental change of circumstances shall not include changes

arising from normal commercial risks. Generally, common commercial risks can be

reasonably anticipated and are assumed by the parties.

During the global economic downturn, most disputes seeking application of Article 26

refer to changes in commercial markets, such as price fluctuations in raw materials or

commodities. When distinguishing “fundamental change of circumstances” and

“commercial risks,” the courts are generally taking a cautious approach and will consider

whether the event could have been reasonably anticipated by the parties.

The Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current Environment provides that

when it comes to a significant increase or decrease in prices of raw materials, changes in

supply and demand, insufficient cash flow and other similar reasons, the people’s courts

shall strictly abide by the principle of fairness and carefully scrutinize the objective

21

Chinese Contract Law, art.117, chap. 7.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 24 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

circumstances alleged by a party.22 Generally, prices of raw materials, supply and

demand, and cash flow issues usually contain lower or more manageable risks than other

market factors such as currency fluctuations or interest risks. Market participants may

conduct routine transactions involving the same raw materials in the same territories.

Such risks are more likely to be seen as routine commercial risks.

For some higher-risk areas, the Supreme Court has called for a strict approach. The

Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current Environment requires much

stricter inspection on commodities that are extremely active on the market such as

petroleum, coal, nonferrous metals, or commodity price indexes and financial product

contracts such as stocks and futures.23

In a recent arbitral award related to swap contracts, the China International Economic and

Trade Arbitration Commission did not recognize the global economic crisis as a

“fundamental change of circumstances.” This decision was based on two reasons:

(1) The global economic crisis was in many respects a gradual process instead

of an abrupt event which caught market participants off guard. The

rationale behind this reason is that as the downturn unfolded, market

participants were able to anticipate and seek solutions to control risks; and

(2) The underlying index of the swap contracts involved in this arbitration

was the Libor interest rate which was recognized as high risk derivative

trading. All parties were aware of such high risks at the time of

contracting. The rationale behind this reason is that if parties are aware of

higher risks through the reasonableness standard, they shall bear such

anticipated risks. In addition, parties that enter into high risk transactions

are hoping to achieve high returns and correspondingly they shall bear any

losses that may arise in these transactions.

This arbitral decision implies that the people’s courts will impose increased scrutiny on

the financial derivative contracts. The global economic crisis will not be generally

recognized as an unanticipated circumstance because these transactions are considered

by a reasonable person to contain high commercial risks.

D. Continuing Performance of Contact is Unfair and Inequitable to One

Party or Objective of Contract Cannot be Fulfilled

This element is the same as that of mandatory rescission whereby a party is entitled to

rescind a contract if the other party breaches ancillary debt obligations after the

expiration of the performance period and such breach frustrates the objective of the

contract.24 Generally, the contract purpose may be described in the contract or inferred

from the negotiations and execution between the parties.

22

Supra note 18.

23

Supra note 18.

24

Supra note 12.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 25 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

On August 25, 2009, the Beijing Chaoyang District People’s Court issued a decision on

an exclusive license agreement suit brought by Song Ying, etc. against Beijing Chang

Xiang Bang Pet Information Consultancy Service Center. In this case, the courts held

that failure to obtain a required license, which partially contributed to a default, would be

considered as a situation where “the objective of the contract cannot be fulfilled.”

This case provides guidance for what may frustrate the purpose of a contract, such as

failure to obtain a required license by one of the parties. In addition, this case provides a

basis whereby if a party’s fault partially contributed to any event which will frustrate the

purpose of the contract, it would be unfair to have the other party perform the contract

and incur losses.

E. Procedures for Claiming Article 26 and the Mediation Policy of the

People’s Courts

A party may request application of Article 26 by filing a request at a people’s court either

as (1) an application to modify an existing contract or as (2) an application to rescind a

contract. Under Article 26, any notice for rescinding a contract by itself does not

effectively rescind the contract.

The Announcement on Serving the State and Communist Party by Correctly Applying

Judicial Interpretation of the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China

II25 provides two policy considerations for applying Article 26: (1) to maintain and

promote a stable financial system and economic growth; and (2) to actively mediate

disputes between parties. These two policies encourage people’s courts to actively

conduct mediations to mutually modify a contract towards a feasible and practicable

resolution.

In practice, if a party requests a contract be rescinded, the people’s courts will first try to

modify the contract based on the principle of fairness. If modification of the contract is

unfair or inequitable to a party, only then will the court will consider the application to

rescind the contract.

F. Cautious Attitudes of People’s Courts on Applying Article 26

The Guidance for Trials on Contract Litigation in the Current Environment provides a

policy objective for the people’s courts to protect the interests of parties who have

performed their contractual obligations in accordance with a valid contract.26 Moreover,

the policy is designed for people’s courts to not permit debtors to escape from performing

their debt repayment obligations.

25

Announcement on Serving the State and Communist Party by Correctly Applying Judicial Interpretation

of the Application of Contract Law of People’s Republic of China II, (Fa [2009] 165) (Promulgated by the

Supreme Court.

26

Supra note 18.

ST1 27240v1 04/05/11

Volume 7, Issue 1 China Law Reporter Page 26 of 30

April 2011 中国法律报道

The SPC requires all people’s courts to conduct very strict reviews on the unanticipated

circumstances alleged by parties seeking modification or rescission.

If, based on the specific situations of individual cases, the court considers applying this

provision, the trial court must first report this case to the high court at the provincial level

for examination and approval. When necessary, the case may also be reported to the SPC

for examination and approval. Having the high court at the provincial level as the

primary authority for applying Article 26 ensures unified application at least by province.

IV. Conclusion