Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kamukhaan: Report On A Poisoned Village

Hochgeladen von

Chandrika Cds DeviOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kamukhaan: Report On A Poisoned Village

Hochgeladen von

Chandrika Cds DeviCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

KAMUKHAAN

REPORT ON A POISONED VILLAGE

Written by Ilang Ilang Quijano

Edited by Jennifer Mourin

Published by Pesticide Action Network (PAN) Asia and the Pacific, December 2002

The place is so barren and desolate, one would think Through constant aerial and ground spraying, the people

that it was abandoned, except that the shabby huts and have been in direct contact with these chemicals for

its impoverished inhabitants are impossible to miss. years, both their health and living environment

withering under their deadly mist. And while the

This is Kamukhaan, a community of 150 families in

perfectly healthy and unscathed bananas produced in

Davao del Sur, Mindanao, Philippines, whose people

the plantation are shipped off, for consumers in foreign

and land have been facing a slow but certain death due

countries to enjoy and major fruit canning industries,

to heavy exposure to pesticides over the past nineteen

the people of Kamukhaan are left to pay the price.

years. The entry of the LADECO banana plantation

situated right next to it in 1981 marked the genesis of Kamukhaan was not the wasteland that it is now. As

poisoning, sickness and poverty. village elders wistfully recall, it was once the picture of

perfect prime: a place so rich in natural resources people

Since then, the village has been subjected to large doses

never went hungry. Trees and vegetation were

of pesticides the plantation utilizes for its own benefit.

PAN AP Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village 1

abundant, and the seas were loaded with marine life. says that: They promised to raise cattle in it. They

The villagers who either fished or grew crops for a living cheated us and we had never been able to recover it.

always had more than enough to feed their families The vast acreage is currently being used by the LADECO

and sustain quite a comfortable lifestyle. The land company for the running of a banana plantation, which

where the banana plantation now stands originally from the beginning promised prosperity, a banana

belonged to the descendants of the Buloy family, part dreamland that would change the lives of the people.

of the Manobo tribe, who rented the property to the Now, virtually no trace of that past life remains to be

Americans during the American Occupation. Diego seen. All that is left is barren land, a contaminated sea,

Buloy, 71, the only living member of the Buloy family and 700 sick and impoverished people breathing in

poisoned air.

Since the plantations expansion in the early 1980s,

the people of Kamukhaan have had to endure aerial

spraying of pesticides which takes place as often as two

to three times a month. Pesticides, which the company

uses to ensure for themselves pest-free, export quality

bananas, are sprayed by an airplane, which sweeps

through the plantation and their entire village. Every

time spraying occurs, the villagers smell strong and

odorous fumes, from which there is no escape, even in

the shelter of their own homes. Their eyes sting painfully

and their skins itch. Most of them experience feelings

of suffocation, weakness and nausea. Alona Tabarlong,

31, elaborates, Children playing in the street come in,

coughing and complaining that their eyes hurt. The

airplane passes our streets, and even when its far away,

the smell of pesticides still reaches inside our homes.

Another villager claims that during aerial spraying, he

is sometimes sprinkled with pesticides, and itchy and

painful skin lesions promptly appear.

Children and adults alike, who rarely became sick before

the plantation came, are now vulnerable to disease.

Skin diseases, abnormalities and various types of illnesses

2 Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village PAN AP

are rampant among the villagers. They easily catch

fever and constantly encounter spells of weakness and

dizziness, vomiting and cough. Many claim to experience

all sorts of body achesstomachaches, backaches and

headacheswhich are aggravated during the periods

of aerial spraying. Several people also suffer various

ailments such as asthma, thyroid cancer, goiter, diorrhea

and anemia. As Edgar Rodriguez, 31, narrates: My

skin has these white spots. Sometimes I have difficulty

breathing. I am often attacked by severe cough and at

times I cant sleep because of it. Linda Manggaga, a

woman in her mid-forties, has a large lump on her neck

that she claimed had been growing for a long time now.

She believes that her weariness, and the growth on her

neck had been the effects of pesticide exposure. Around

1981, she recalls, I was on my way to sell wood when

I smelt strong fumes and fell very ill. Then years later,

I discovered this huge lump on my throat.

Infants are often born sick, and with abnormalities

ranging from cleft lip and palate to badly disfigured

bodies. Several children are born with severe skin An example is Lilibeth Hitalia, an 8 year old child who

abnormalities. Infants dying at birth or shortly after are is constantly rushed to the hospital because of diarrhea.

not rare. When Rebecca Dolka, 36, bore her child, it She was already 4 years old when she started to speak.

was lifeless, its body and eyes yellow in color. I didnt She has great difficulty in understanding things, and

expect that the pesticides I inhaled would affect my also was born too small, her mother relates.

pregnancy, she said. Consistent exposure to pesticides

have also proven to be an impediment in childrens A number of adults have also been diagnosed with more

mental and physical development. Children are often serious, terminal diseases such as cancer. Many more

behind in their studies, and are often absent in class have died of various contracted diseases. A village

due to sicknesses. officer, Leonardo Tigaw, testified that in one month

alone 5 people died because of diorrhea and fever.

Michael Bakiran, 31, said that his mother constantly

complained of the pesticide fumes and

suspected that she died precisely because of

this. Her stomach became enlarged, and she

became weak. The hospital diagnosed it as a

complicated disease and she died 2 weeks

after. Nanette Rodriguez, 37, narrates,

Several people have already died and many

became sick, so we appealed to the manager

of the plantation. But he said that they refused

to pay the hospital bills if the illnesses are caused

by our water and not by the pesticides, even

when hospital doctors say that our water supply

is contaminated by the pesticides that seep into

our soil. Thats also the reason why so many

people get sick, and spend so much. Others

dont even reach the hospital alive. Apparently,

constant deaths caused by diseases, ranging

PAN AP Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village 3

from the simple to complicated, have horrifyingly

plagued the people for years. Just recently another

villager testifies, a woman lost two of her children.

Moreover, growth of plant life in the village has also

been seriously stunted. When exposure to pesticides

started, the coconut trees suddenly stopped bearing fruit

so the villagers were left with no other choice but to

cut them down. The chemicals the plantation uses

might be good for their banana crops, but on our coconut

trees, it is destructive, says Nanette Rodriguez, a

villager. Their soil, too, had become infertile, so growing

crops for food and income has now become very difficult.

Planting food was suddenly not an option they could

afford anymore. Even grass grew scantily among the

place. Raising pigs, chickens and other animals also

proved very difficult because increasing numbers of them

would die every time spraying occurred. Animals that

wandered into the plantation or fed on the grass near

their property also met their death. The villagers also

believe that their streams have been contaminated as

well, because many animals refuse to drink from it and

the animals that do consume the water eventually die.

Aside from the aerial spraying, the plantation also

ground-sprays their banana crops using chemicals such

as Furadan and Nemacur, both of which have been

labeled as extremely hazardous. The village people

believe that their underground water supply, which lies

180 feet deep, has long since been contaminated with

pesticides. During the rainy season, rains wash over

the plantations land and the pesticide-riddled water

flows into the village where it rises up to as high as

waist-level. As a result, the villagers who unavoidably

wade in it, and the children who play in it, get ill.

An even worse predicament for the village is the fact

that the river and the sea, both of which have been

one of their major sources for food and income before,

have not been spared from pesticide contamination.

Their waters, which used to be teeming with fish, are

now heavily polluted with chemicals. Fishermen recall

a time 30 years ago, when we used to garner up to

200 kilos of fish everyday. Now we are lucky if we can

catch 2 kilos of it. They have also observed the regular

occurrence of fish kills, when before there used to be

none. And due to extreme poverty people cannot avoid

4 Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village PAN AP

consequently ended up losing two toes and ended up

with a badly infected footthe treatment for which he

had to pay on his own. Another companion of his, who

was doing similar work, was more unfortunate and

eventually died of cancer of the foot.

Pesticide applicators inject pesticides to the bananas or

directly spray it by backpack, some doing it as often as

on a daily basis. Two laborers who had used

GRAMOXONE (the trade name for paraquat) as spray

were hospitalized, and one of them died. The other

workers experience dizziness, weakness, and skin itching,

and are absent from work almost once a week because

of their illnesses. Edward Rama, who injects BAYCOR

and DECIS every week to banana buds, said that he is

always feverish, experiences stomach aches, has skin

that constantly itches, and tires easily. Jose Antermo,

30, used FORMALIN daily, and he regularly experienced

spells of weakness and dizziness. FORMALIN is painful

to the nose, and my chest tightens when I smell it. My

wife, she lost our child when she was 4 months pregnant.

I think it was because of my job. She washes my work

clothes doused with FORMALIN. Laborers who had

served in the plantation for a long period of time

eating the contaminated fish, and they end up getting

sick as a result. Complaints have been repeatedly

brought up to the plantation owners but the owners

have refused to claim responsibility for the

contamination of the sea and other water sources. The

fishermen then tried to appeal to provincial authorities.

They even took samples of the dead specimens, water,

and soil to the town hall, but again their pleas merely

fell on deaf ears and no definite action was taken.

With pesticides destroying the natural life from the land

and water they were dependent on, the villagers who

never went hungry before suddenly found themselves

going to bed with empty stomachs. The blondeness

among several of the children are tell-tale signs of

malnutrition and protein deficiency.

When being farmers or fishermen alone made survival

virtually impossible, most of the men in the community

were forced to work as laborers in the plantation. They

are usually employed as drainage workers and pesticide

applicators, working in direct contact with the chemicals,

wearing little or no protective clothing at all. One laborer

narrates that his job involved walking through canals of

waste materials, wherein the chemical-laced waters

reached his thighs, thus rendering his boots useless. He

PAN AP Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village 5

gradually became too weak and sickly to continue, and

had to stop working altogether.

These workers are obviously involved in risky work,

which affects their health. But they only receive a

miniscule salary in return. The average employee who

works in these extremely hazardous conditions, from

morning until sundown, only earns about 45 pesos (US

$1.1) a day. Sometimes, we receive 90 pesos, if we

finish a lot, says one of them. This small amount of

money the workers receive is well below the threshold

income to be able to buy food that would sufficiently

sustain their families. Oftentimes, these workers do

not receive the medical treatment they badly need

because they cannot afford to pay for it themselves.

The plantation refuses to grant employees a raise in

their salaries and could not be expected to pay for their

hospital bills. One employee reported that he does not

even get paid his salary, but is given food instead. He

claimed that he was promised 9 pesos per cubic meter.

And for the 6 cubic meters he manages to dig per day:

I should be given 54 pesos a day but instead I get 5

kilos of rice every week that is supposed to be enough

to feed my family of four. He has tried to complain

about this unfair arrangement but according to him the

labour contractor is never around.

Some people, desperate for a living even sell ipil-ipil

leaves (an ingredient for animal feed) for 2 pesos per

kilo and earn the measly sum of 100 pesos a week.

6 Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village PAN AP

With their health fast deteriorating, their food supply deserve. It is in far-flung villages like Kamukhaan where

seriously depleted, their land destroyed and with no other the picture of globalization and human greed is most

source of income sufficient enough, the people of clearly depicted.

Kamukhaan may not be too far away from extinction, unless

The survivors of this community have presented their

they find an effective antidote to their poisoned lives.

plight, which clearly reveals the grave impact pesticides

The plantation is nonchalant when confronted with use has on peoples lives. How it has caused the

complaints about their unsafe pesticide operations, and degeneration of Kamukhaan from a near natural

the local authorities likewise proved to be of no help to paradise into a living hell. The damage can only be

them. A village elder says with resignation, Weve undone with the aid of people who value the intrinsic

tried, but as much as we want to, we cannot do anything worth of human life over any amount of money or profit.

about it anymore. It is very powerful people we are

Perhaps by working hand in hand with the people of

up against.

Kamukhaan to rebuild their homes and lives, we may

Would man go as far as to slowly and painstakingly be one in our hope in making this world a much safer

destroy more than 700 lives in the name of profit? place for ourselves, for our children, and for the future.

Apparently, yes. In a land reeking with disease, coupled But as long as villages like Kamukhaan exist, the battle

with poverty, the survival of the people of Kamukhaan against injustice, human greed and oppression will and

barely hangs by a thread. By relating their observations must continue.

and what they have endured through the years, they

are literally crying out for help. Too deeply mired in

their state of sickness, poverty and hopelessness, For further information on the Kamukhaan Community

perhaps it is the only thing that they can do. and How you can help contact:

But we can help by supporting communities who are Dr. Romeo F. Quijano, President, PAN Philippines,

struggling to lift themselves up from places that profit- Lot 2, Block 30, Salome Tan street, BF Executive

hungry corporations have religated them, to once more Village, Las Pinas, Metro Manila, Philippines. Tel/

give them a glimpse of the life that they once had and Fax: 63-2-5218251 E-mail: romyquij@yahoo.com

PAN AP Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village 7

The Pesticide Action Network (PAN) is an international coalition of citizens

groups and individuals who oppose the misuse and overuse of pesticides, and

support the reliance on safe and sustainable alternatives. Established in 1982,

the PAN international network presently links over 300 groups in 50 countries,

and is coordinated through five regional coordinating centers. PAN is a network

and no individual can direct or represent the entire coalition. Participants are

free to pursue their own projects to further PANs objectives, and benefit

from their access to the collective resources of the network.

PAN Asia and the Pacific (PAN AP) is based in Penang, Malaysia. We are

linked to more than 150 groups, in 18 countries in the Asia Pacific region.

The Vision Statement of PAN Asia and the Pacific, as adopted at the 1996 and

2000 Steering Council Meetings, states:

WE believe in people-centered, pro-women, development through sustainable

agriculture;

WE are committed to protect the safety and health of people and the environment

from pesticide use, and genetic engineering in food and agriculture;

WE will achieve these goals by empowering people within effective networks at the

Asia Pacific and global levels.

PAN AP prescribes to the following development principles: a participatory

holistic approach; a commitment to gender equity and genuine partnership;

the need to confront social injustice and global inequities; the value of

biodiversity, appropriate traditional and indigenous knowledge systems; and

the recognition that our earth is one interdependent living system.

Pesticide Action Network (PAN) Asia and the Pacific

P. O. Box: 1170, 10850 Penang, MALAYSIA

Tel: (604) 657 0271 / 656 0381 Fax: (604) 657 7445

Email: panap@panap.net

Home page: www.panap.net

8 Kamukhaan: A Poisoned Village PAN AP

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Invasive SpeciesDokument22 SeitenInvasive Speciesapi-3706215Noch keine Bewertungen

- Impacts of Land-use Change on the EnvironmentDokument8 SeitenImpacts of Land-use Change on the EnvironmentMariel Adie TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMO Training Slides - 29 January 2021Dokument598 SeitenAMO Training Slides - 29 January 2021MeAn UmaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pests, Diseases and Beneficials: Friends and Foes of Australian GardensVon EverandPests, Diseases and Beneficials: Friends and Foes of Australian GardensBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Drinking Water PurificationDokument26 SeitenDrinking Water PurificationShubhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pyramid 1978 Book Les BrownDokument29 SeitenThe Pyramid 1978 Book Les Brownhistorymakeover100% (1)

- Disaster Readiness and Risk Reduction: Disasters and Its Effects Learning From Weakness Why Us? Not Others?Dokument8 SeitenDisaster Readiness and Risk Reduction: Disasters and Its Effects Learning From Weakness Why Us? Not Others?Eli67% (12)

- Dairy Etp CalculationsDokument7 SeitenDairy Etp CalculationsSagar Apte100% (1)

- Presentation # 3 Pre Treatment For SWRO Plants PDFDokument22 SeitenPresentation # 3 Pre Treatment For SWRO Plants PDFMahad QaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Waste Collector Research MaterialDokument12 SeitenWater Waste Collector Research MaterialJanna May Villafuerte100% (1)

- Test 3Dokument12 SeitenTest 3Hiền Cao MinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Folleto Tríptico de Masajes Tipográfico Verde y Beife Con Detalles Fotográficos para Especialista en Masaje Shiatsu Con TestimoniosDokument2 SeitenFolleto Tríptico de Masajes Tipográfico Verde y Beife Con Detalles Fotográficos para Especialista en Masaje Shiatsu Con TestimoniosDula PeepNoch keine Bewertungen

- Demographic and Genetic Phenomena Destruction of Wild Habitats Introduction of Invasive Species Climate ChangeDokument4 SeitenDemographic and Genetic Phenomena Destruction of Wild Habitats Introduction of Invasive Species Climate ChangeAnh Lê Thị TúNoch keine Bewertungen

- Air Pollution 4. Noise & Light PollutionDokument3 SeitenAir Pollution 4. Noise & Light Pollutionclara olsenNoch keine Bewertungen

- DRR Module 3Dokument4 SeitenDRR Module 3Jasmin BelarminoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Actividad de Inglés - JairoDokument5 SeitenActividad de Inglés - Jairojairoc2008Noch keine Bewertungen

- Activity 3 Tiburcio, Patrick F. - Btvted 2-L DT ADokument2 SeitenActivity 3 Tiburcio, Patrick F. - Btvted 2-L DT APatrick F. TiburcioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research About An Invader in Your CountryDokument2 SeitenResearch About An Invader in Your CountryDANIEL SANTIAGO GUAVITA RODRIGUEZNoch keine Bewertungen

- African Jungle Women Living Life Just Living Book 2: Sara’s Uncomplicated Life Thereafter Associated with the White ManVon EverandAfrican Jungle Women Living Life Just Living Book 2: Sara’s Uncomplicated Life Thereafter Associated with the White ManNoch keine Bewertungen

- Home Is Where The Harm Is: Inadequate Housing As A Public Health CrisisDokument6 SeitenHome Is Where The Harm Is: Inadequate Housing As A Public Health CrisisDeivy Gustavo Gonzales RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Invasive Species BrochureDokument2 SeitenInvasive Species Brochureapi-321377965Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kentucky Pest News August 17, 2010Dokument7 SeitenKentucky Pest News August 17, 2010awpmaintNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Pollution NotesDokument1 SeiteWater Pollution NotesMary Francesca CobradoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Pandemic On Flora and FaunaDokument22 SeitenImpact of Pandemic On Flora and FaunaAsmi MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wa1 Gee6Dokument7 SeitenWa1 Gee6MAR ANTHONY JOSEPH ALVARANNoch keine Bewertungen

- PODCASTDokument3 SeitenPODCASTtim80924Noch keine Bewertungen

- Activity 22-23-24-25 StsDokument8 SeitenActivity 22-23-24-25 StsMarizuela QuidayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Studies Biodiversity DegradationDokument10 SeitenCase Studies Biodiversity DegradationDiecast RadiationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colombia fails to tackle malnutrition crisis among Indigenous childrenDokument2 SeitenColombia fails to tackle malnutrition crisis among Indigenous childrenJ412Noch keine Bewertungen

- Carson's Silent Spring Highlights Threats of Unchecked Pesticide UseDokument10 SeitenCarson's Silent Spring Highlights Threats of Unchecked Pesticide UsenuclearlaunchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Module Week 2 Quarter 1Dokument5 SeitenHealth Module Week 2 Quarter 1delda.janikaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journey to Discover How Environmental Changes Spread Deadly Diseases Like Malaria, Dengue & CholeraDokument3 SeitenJourney to Discover How Environmental Changes Spread Deadly Diseases Like Malaria, Dengue & CholeraNaomiGrahamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 2Dokument19 SeitenTask 2Paula CardozoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silent SpringDokument3 SeitenSilent Springapi-423260675Noch keine Bewertungen

- Q1COT PPT-HEALTH9TypesofEnvironmentalIssuesAutosavedDokument42 SeitenQ1COT PPT-HEALTH9TypesofEnvironmentalIssuesAutosavedJessa May Fernandez CaranooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avocados and Vanilla ExtinctionDokument2 SeitenAvocados and Vanilla ExtinctionAlfonso El SabioNoch keine Bewertungen

- DiscoveriesDokument6 SeitenDiscoveriesRoland WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Invasive Species BrochureDokument3 SeitenInvasive Species Brochureapi-468903777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Task in Science V: Submitted By: Briana Chaellean R. Dandoy Grade V - Tunny FishDokument10 SeitenPerformance Task in Science V: Submitted By: Briana Chaellean R. Dandoy Grade V - Tunny FishApril DandoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Off White Vintage Newspaper Style NewsletterDokument10 SeitenOff White Vintage Newspaper Style Newsletterapi-431100088Noch keine Bewertungen

- PP 2Dokument1 SeitePP 2api-311321957Noch keine Bewertungen

- Group 2-BiodiversityDokument37 SeitenGroup 2-BiodiversityVillanueva, Alwyn Shem T.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eng SDokument9 SeitenEng Sapi-3700197Noch keine Bewertungen

- BiodiversityDokument1 SeiteBiodiversityHartford CourantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review Silent Spring 190210Dokument9 SeitenBook Review Silent Spring 190210api-457299267Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Portfolio Part 4 Term 222 1Dokument17 SeitenReading Portfolio Part 4 Term 222 1wewswf1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Deforestation's Impact on EnvironmentDokument10 SeitenDeforestation's Impact on EnvironmentJethalal GadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mining IssuesDokument4 SeitenMining Issuescool joesNoch keine Bewertungen

- DRRR ModuleDokument148 SeitenDRRR Modulemichael hobayanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task 2 - Writing ProductionDokument8 SeitenTask 2 - Writing ProductionOscar AponteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Household & Public HealthDokument3 SeitenHousehold & Public HealthmdollNoch keine Bewertungen

- Climate Change: Technological University of The PhilippinesDokument2 SeitenClimate Change: Technological University of The PhilippinesShexaniho RonquilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passage A - The Healer PDFDokument2 SeitenPassage A - The Healer PDFdillipinactionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Indigenous Peoples: Gee6 Written Assessment No.1Dokument6 SeitenIntroduction To Indigenous Peoples: Gee6 Written Assessment No.1Fainted HopeNoch keine Bewertungen

- News 2005 04Dokument4 SeitenNews 2005 04Geoff BondNoch keine Bewertungen

- Silent KillerDokument23 SeitenSilent KillerRakesh BalakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011 - Pringle Encyclopedia Invasive SPPDokument5 Seiten2011 - Pringle Encyclopedia Invasive SPPAbdullahi Rabiu KurfiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shrimp Farming Case StudyDokument64 SeitenShrimp Farming Case StudyPichakornNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Investigatory Project (Recovered)Dokument25 SeitenBiology Investigatory Project (Recovered)shubham25% (4)

- 2nd Semester SUMMARIESDokument9 Seiten2nd Semester SUMMARIESiibbyy00123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Activity 3Dokument2 SeitenActivity 3Espiritu, ChriscelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 2: Worksheet No. 1: Social Issues Identified Problem Possible SolutionsDokument3 SeitenModule 2: Worksheet No. 1: Social Issues Identified Problem Possible SolutionsDavina DavinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health and SafetyDokument4 SeitenHealth and SafetyRhoxane SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marine Pollution Sources, Effects, and SolutionsDokument8 SeitenMarine Pollution Sources, Effects, and SolutionsStephen Jude BolondroNoch keine Bewertungen

- FInal NSTP ActivityDokument2 SeitenFInal NSTP ActivityElixer ReolalasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Of of The: Killed in by ElephantsDokument4 SeitenOf of The: Killed in by ElephantsMeiraba ChanambamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1.9 SBRDokument11 Seiten1.9 SBRAbdul rahmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment of Waste Water Quality of Sewage Treatment Plant-A Case StudyDokument5 SeitenAssessment of Waste Water Quality of Sewage Treatment Plant-A Case StudyAkari SoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Conservation Guidelines and Plans in ZambiaDokument56 SeitenWater Conservation Guidelines and Plans in ZambiaCharles ChisangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHN EnvironmentDokument3 SeitenCHN Environmentsadaf parveezNoch keine Bewertungen

- DPHE ITN 2006 WSP For Rain Water HarvestingDokument16 SeitenDPHE ITN 2006 WSP For Rain Water HarvestingPoppyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determining the Effects of PCBs on Periwinkles and Crabs in Lagos Lagoon SedimentsDokument10 SeitenDetermining the Effects of PCBs on Periwinkles and Crabs in Lagos Lagoon SedimentsAkpan EkomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 6 - Water ResourcesDokument4 SeitenModule 6 - Water ResourcesLouie DelavegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dirty Water-Pollution Problems PersistDokument6 SeitenDirty Water-Pollution Problems Persistshahan lodhiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Monitoring Pollution Level of The River KhiruDokument6 SeitenMonitoring Pollution Level of The River KhiruNusrat Jahan RiteNoch keine Bewertungen

- SMR FORM April To June 2021Dokument12 SeitenSMR FORM April To June 2021Jonathan CatalonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sewage Treatment PlantDokument129 SeitenSewage Treatment PlantzfrlNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ieee FormatDokument4 SeitenIeee FormatClydeG.SepadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Pollution: Presented By: Esther NG E-Jo Jordan Teah Hong Yek Joan Cheah Ern Lin Teh Wen Paul Teoh Shu WeiDokument24 SeitenWater Pollution: Presented By: Esther NG E-Jo Jordan Teah Hong Yek Joan Cheah Ern Lin Teh Wen Paul Teoh Shu WeiESTHER NG E-JO MoeNoch keine Bewertungen

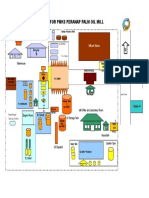

- PMKS Palm Oil Mill Layout PlanDokument1 SeitePMKS Palm Oil Mill Layout PlanSalim Siregar100% (1)

- Microorganisms in Drinking Water: Types, Sources, and SafetyDokument10 SeitenMicroorganisms in Drinking Water: Types, Sources, and SafetyRaihana NesreenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Article: Water Pollution and Water Quality Assessment of Major Transboundary Rivers From Banat (Romania)Dokument9 SeitenResearch Article: Water Pollution and Water Quality Assessment of Major Transboundary Rivers From Banat (Romania)Jhosa Yna AnireNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review: The Real Time Water Quality Monitoring System Based On IoT PlatformDokument4 SeitenA Review: The Real Time Water Quality Monitoring System Based On IoT PlatformEditor IJRITCCNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 SUEZ Industrial (Process) Membranes ListDokument1 Seite2 SUEZ Industrial (Process) Membranes ListcarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson PlanDokument5 SeitenLesson PlanSyahir HadziqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module 1 - Urban Planning - 2021-1Dokument150 SeitenModule 1 - Urban Planning - 2021-1SREYAS K MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 3Dokument45 SeitenChapter 3samuel TesfayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- West Virginia Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual FULL November 2012-V2Dokument502 SeitenWest Virginia Stormwater Management and Design Guidance Manual FULL November 2012-V2Nimco CadayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handling of By-Products and Treatment of WasteDokument7 SeitenHandling of By-Products and Treatment of WastezalabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- KAP Customer Satisfaction Survey Questionnaire FinalDokument7 SeitenKAP Customer Satisfaction Survey Questionnaire FinalBongga Ka DayNoch keine Bewertungen