Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

HRM Strategies in China An Entrepreneurship Perspective

Hochgeladen von

Randy JosephOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

HRM Strategies in China An Entrepreneurship Perspective

Hochgeladen von

Randy JosephCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 19, No.

5, May 2008, 945963

Modelling regional HRM strategies in China: An entrepreneurship perspective

Zhong-Ming Wanga* and Sheng Wangb

a

Zhejiang University, China; bUniversity of Nevada, Las Vegas, USA

With the rapid development of organizational change and globalization in China, most Chinese rms are preparing themselves for doing business across regions and going global through effective strategic entrepreneurship and human resource management (HRM). This study examines the relationship between two general HRM practices, strategic entrepreneurship and organizational performance, in order to build up a cross-regional HRM strategy model. Participants in the study constituted 103 rms from 11 different cities and provinces. In each company, three types of surveys were distributed: an HRM practice survey (career development and performance management), a strategic entrepreneurship survey and an organizational performance survey among two human resource (HR) managers, two three executives and two three members of top management teams, respectively. Altogether 606 managers and executives participated from across regions in China. The results showed that performance management was positively related to organizational performance and such relationship was stronger when adaptive capability, one dimension of strategic entrepreneurship, was higher. The performance management organizational performance relationship was also found to vary across regions. Moreover, two other dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship, proactive change and risk anticipation, were found to have effects on organizational performance. The implications of the ndings are discussed. Keywords: career development; China; HRM; performance management; regional analysis; strategic entrepreneurship

Introduction The rapid economic growth since economic reforms were launched and the open door policy initiated in 1978 in China has increasingly attracted the attention of academic researchers (e.g., Luo 1995; Child 1999; Warner 1999; Law, Tse and Zhou 2003; Atuahene-Gima and Li 2004; Zhou, WU and Luo 2007). With the entry of China into the WTO and the implementation of various regional development policies and entrepreneurship, it is timely to understand how rms in China may enhance performance and gain competitive advantage across domestic regions and in this more globalized and increasingly competitive market. Among recent developments in China, entrepreneurship, as one of the major approaches to business development, has been emphasized and in the meantime, human resource management (HRM) practices are particularly important in supporting such an approach (Wang and Zang 2005). Indeed, human resources have been identied as a critical source of sustainable competitive advantage (Wright, McMahon and McWilliams 1994; Wright and Barney 1998). Despite much research on entrepreneurship

*Corresponding author. Email: zmwang@zju.edu.cn; sheng.wang@unlv.edu

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online q 2008 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/09585190801994107 http://www.informaworld.com

946

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

in Western countries (e.g., Zahra, Jenning and Kuratko 1999; Daily, McDougall, Coving and Dalton 2002; Covin, Green and Slevin 2006), research in China, the largest emerging economy, has been active but still lagging behind (Liu, Luo and Shi 2003; Luo, Zhou and Li 2005). More and more studies focus on regional policies and HRM practices (Wang and Zang 2005). In coping with the challenges of the economic reform and rapid organizational changes, HRM research in China has shifted its focus from more functional HRM practices to more integrated HRM development and strategic HRM practices (Wang 2006). It is important, given recent HRM studies conducted under the context of organizational reform and innovation, that we introduce a strategic entrepreneurship perspective and more regional considerations into studies in this eld. Moreover, because of the different pace of economic reform, various regions in China offer different external environments in which rms operate (Liu, Luo and Shi 1999). Although there has been some research that shows the regional differences in the adoption of HRM practices (e.g., Ding, Goodall and Warner 2000), the question still remains as to how the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance is contingent upon regional policies and how strategic entrepreneurship might affect this relationship. In this study, to address the questions and issues raised, we identify two important HRM practices in the Chinese context, career development and performance management, and the dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship in China, and then examine their inuences on organizational performance. Additionally, we investigate the moderating role of regional differences on the relationships between the two HRM practices and organizational performance. In the following sections, we rst review literature related to HRM practices, strategic entrepreneurship and regional differences to develop our hypotheses. Then we present the empirical analysis of our research. Finally, we discuss the results and conclude with the implications of our ndings, study limitations and potential for future research. Literature review In the past 15 years, more and more rms have been conducting business across regions in China and are preparing themselves for going global. One of the key strategies has been adopting effective HRM practices. This includes two aspects: (1) building up regional models of effective HRM approaches along with organizational characteristics; (2) understanding challenges in HRM practices in working with regional development and entrepreneurship strategies. In the area of entrepreneurship, cross-regional mergers, acquisitions, joint ventures and business alliances were among the popular business strategies for developing larger and stronger rms (Siu and Liu 2005). However, in many Chinese cases of mergers, HRM was a bottleneck (Wang and Mobley 1999). Therefore, more specic HRM strategies were urgently needed for supporting organizational change, technological innovation and entrepreneurial development (Wang 2006). Among most Chinese rms, there was a lack of strategy-level integration of HRM practices with entrepreneurship, and different HRM approaches were often less effective in terms of sustainability (Wang and Mobley 1999). How do strategic entrepreneurship and HRM practices affect aspects of organizational performance? Johnson and Van de Ven (2002) used the resource-based perspective to develop the framework for entrepreneurial strategy. More recently, Borch and Madsen (2005) studied innovative SMEs and found a relationship between adaptive capability and entrepreneurship strategies. White (2000) demonstrated signicant effects of external

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

947

environment and internal capacities on technology decisions among Chinese state-owned enterprises. The theoretical development has provided basic constructs and thinking for developing a new framework for this study. Some key issues are addressed in relation to previous research on HRM modelling across regions. First, previous studies mentioned regional differences in economic conditions (e.g., Liu et al. 1999; Ding et al. 2000; Ding, Akhtar and Ge 2006) but neglected the regional analysis of HRM practices in relation to rm performance. Second, although there were a few studies on comparing HRM practices among ownerships (state, collective, foreign-funded and private sectors) (e.g., Zhu 2005), little research has examined the relationship between strategic entrepreneurship, HRM practices and organizational performance across regions by controlling characteristics such as ownership, size and rm developmental phases. It has been suggested that research in HRM and business strategies should focus more on regional and strategic modelling of effective HRM (Tsui and Lau 2002; Wang 2006). There has been an increasing demand for integrated strategies of HRM practices and strategic entrepreneurship across regions (Wang and Mobley 1999; Wang and Zang 2005; Wang 2006). Figure 1 presents the conceptual model among strategic entrepreneurship, the two HRM practices of interest in the study, and rm performance. Hypotheses development According to the resource-based view of the rm (c.f., Barney 1991; Wright et al. 1994), employees are considered human resource capital. If utilized well, this resource will be able to contribute to the competitive advantage of rms (Barney and Wright 1998). That is, how human resources are utilized and treated will likely affect organizational performance. Prior research in the western context has related HRM practices to

Figure 1.

The relationship between strategic entrepreneurship, HRM practices and rm performance.

948

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

rm performance. For example, Huselid and his colleagues (1997) showed that HRM effectiveness was positively related to productivity and market value of rm performance. Delaney and Huselid (1996) found positive associations between HRM practices and perceptual measures of rm performance. HRM practices have also been the focus of several cross-cultural studies in China (Satow and Wang 1994; Wang and Satow 1994; Verburg, Drenth, Koopman, Van Muijen and Wang 1999). We believe that two HRM practices, performance management and career development, are of particular interest in this study for the following reasons. In the past, especially before the economic reforms of 1978, state-ownership dominated the economy and HRM practices were limited to more functional activities. The evaluation of performance focused more on task accomplishment. Great differentiation among employees was not desirable largely because of the Chinese tradition of harmony (Chow 2004). There was no tight connection between performance and pay and performance appraisals were not conducted in a systematic and periodic fashion. Career opportunities were largely based on seniority rather than performance. Under the system of the iron rice bowl and with the virtue of harmony, there was not enough motivation for employees to pursue more developmental opportunities either. Due to institutional continuity (Warner 1999), it is difcult for many organizations to completely change such practices in a very short time. Both performance management and career development, which diverge from traditional HRM practices, may play a strategic role in organizations. Performance management involving organizational components links employees goals and behaviour with the organizations strategic goals. When on-going feedback is provided to the employees, they understand where their efforts should be directed to help achieve organizational goals. It helps improve processes within the organization and can affect business outcomes (Rummler and Brache 1990; Schuler, Fulkerson and Dowling 1991). McDonald and Smith (1995) provided some evidence that linked performance management to organizational performance. Using family-owned SMEs, Carlson and colleagues (2006) also found a positive relationship between the use of performance appraisals and sales growth. Career development, on the other hand, provides the opportunity for employees to grow and excel within the organization. This also allows employees to develop skills, acquire knowledge, and improve their competencies that may contribute to the organization in the long run. Moreover, this sends a signal of organizations commitment to their employees, which in turn leads to higher employee motivation and morale. Indeed, it has been argued that employee development is a key driver to organizational growth and adds value to organizations (Mayo 2000). Therefore, we expect the extent to which performance management and career development are used will contribute to organizational performance. Hypothesis 1: Performance management will have a positive inuence on organizational performance. Hypothesis 2: Career development will have a positive inuence on organizational performance. Research has suggested that rm strategies can have a direct impact on its performance in certain contexts (e.g., Chow and Liu 2007; Menguc, Auh and Shi 2007; Sun, Aryee and Law 2007). It has also been argued that entrepreneurship can contribute to rm performance and revitalization. Corporate entrepreneurship focuses on creating new business, innovation and growth (Zahra 1991) and is also characterized by seeking and seizing opportunities (McCline, Bhat and Baj 2000; Peng 2001). Some research has shown that entrepreneurship is likely to be

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

949

associated with nancial performance of organizations (e.g., Zahra 1991; Zahra and Covin 1995; Antoncic 2006). In emerging economies in particular, strategic entrepreneurship has increasingly been recognized as a stimulus for wealth creation (Peng 2001). For example, Bruton and Rubanik (2002) found that the more innovative the companies were the more likely they would grow effectively in a transition economy. In developing a construct and dimensional model of strategic entrepreneurship, Ireland et al. (2003) suggested that strategic entrepreneurship involves simultaneous opportunityseeking and advantage-seeking behaviour that result in superior rm performance and that strategic entrepreneurship has four dimensions: entrepreneurial mind-set; entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial leadership; strategic management of resources; and applying creativity to develop innovations. Yang (2002) argued for an analytic framework for double entrepreneurship in Chinas economic reforms. That is, on the one hand, an entrepreneur has to be innovative and to be able to identify promising new possibilities but on the other hand, it is also important to be adaptable and able to make adjustments and to take advantage of rules and regulations. In a review of adaptive capabilities, Wang and Ahmed (2007) identied three components for dynamic capabilities: adaptive capability; absorptive capability; and innovative capability. Among the Chinese rms, adaptive capability is more closely related to coordinating efforts and adjusting structures or systems. Innovative capability is more related to acquiring resources for innovation and adopting resources to motivate innovative activities. Zahra et al. (2005) also identify change actions and challenge coping as key strategies for entrepreneurship. Based on previous theoretical developments and Chinese regional entrepreneurial development and organizational change, in this study, we dene strategic entrepreneurship as a four-factor concept: adaptive capability; resourceful innovation; proactive change; and risk anticipation. Adaptive capability represents ability in coordinating, facilitating, adjusting, leading and adapting organizational resources for entrepreneurial and business development; resourceful innovation is the strategic management of resources that encourages new ideas and develops innovative projects through mobilizing effective resources and establishing systems for entrepreneurship and creativity; proactive change focuses on strategic change actions and active organization development, whereas risk anticipation represents the ability to recognize current difculties and challenges and build up the readiness for entrepreneurial actions. We expect these four dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship to be positively related to organizational performance. Moreover, the nature of adaptive capability suggests that it may serve as a moderator, as this capability facilitates the use of resources. A high level of adaptive capability will help a rm to better align their internal resources with encountered demands (Rindova and Kotha 2001). In the meantime, human resources are among the most important resources that may be coordinated and adapted for achieving organizational goals. Thus, we expect a moderating effect of adaptive capability such that the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance would be stronger with a higher level of adaptive capability. Hypothesis Hypothesis Hypothesis Hypothesis Hypothesis 3a: Adaptive capability will positively affect organizational performance. 3b: Resourceful innovation will positively affect organizational performance. 3c: Proactive change will positively affect organizational performance. 3d: Risk anticipation will positively affect organizational performance. 3e: Adaptive capability will moderate the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance

950

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

Several regional strategic actions need to be mentioned in order to fully understand the dynamics of HRM, entrepreneurship and rm performance. First, the western-China development strategy was launched during mid-1990s in order to attract more talented people and promote economic development in the region. The challenge is that talented people traditionally move to the eastern coast areas. It becomes more difcult to attract the best people in the central and western regions. Second, during late 1990s, the northern-China revitalization development strategy was implemented in a region of heavy industry with a large number of downsized labour forces. More recently a comprehensive mid-China development strategy was announced in order to cope with the lack of vital HRM. In the meantime, the Yangtze River Delta area has been seen as the most active entrepreneurship region, with active technological innovation and global entrepreneurship. These regional development policies have greatly promoted HRM strategic modelling strategic entrepreneurship in China. Despite the economic reform period in China, the eastern coast region has enjoyed much higher economy growth rate compared to the central and western regions which are located in inland China. Along the coastal region, special economic zones and open coastal cities have been created as an open platform for economic development. This region also offers favourable policies to foreign and local enterprises such as preferential tax incentives, organizational autonomy in recruitment and compensation, and support from the government. The region has attracted much foreign direct investment (FDI) which brings with it high technology, modern equipment, advanced practices and high levels of skills (see Caves 1996). As a result, the area is relatively more developed than the western and central regions of China. With a high concentration of FDI on the eastern coast and fast economic growth, this region provides better access to specialized, experienced and welleducated employees (see Porter 1998). Multinational enterprises (MNEs) also help improve the skill and knowledge levels of the labour market indirectly as their employees move to local rms (Blomstrom and Kokko 1998; Buckley, Clegg and Wang 2002). Moreover, Ding and his colleagues (2000) found that the average wages were signicantly higher in rms located in coastal China than inland China. The high economy growth rate, which signals more job opportunities, and the high compensation level attract talented individuals from other locations to the eastern coast cities and provinces. With a larger pool of talents, rms in the eastern regions are more likely to gain higher levels of human capital. However, in the western and central regions, it is relatively difcult to attract, hire and retain individuals with best skills and knowledge. Therefore, we hypothesize the following: Hypothesis 4: The relationship between performance management and organizational performance is stronger for rms located in the eastern region compared to those in the western and central regions. Hypothesis 5: The relationship between career development and organizational performance is stronger for rms located in the eastern region compared to those in the western and central regions

Methodology Participants The study involved 103 rms from 11 different cities and provinces. They were from Shanghai, Zhejiang (Hangzhou, Wenzhou, Ningbo), Shandong (Qingdao), Hubei (Wuhan), Hunan (Changsha), Guangxi (Guilin), Shanxi (Xian), Guizhou (Guiyang) and Yunnan

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

951

(Kunming). Altogether, 606 employees participated in the study. In each company, an in-depth interview was conducted and three surveys about HRM, strategic entrepreneurship and organizational performance were distributed among two HR managers, two three executives, and two three top management members, respectively. About 34 bureau ofcials also participated in the study, serving as external raters of organizational performance. The HRM practices survey was completed by 180 HR managers. The strategic entrepreneurship survey was conducted among 173 executives and the organizational performance survey was completed by 219 top managers and 34 bureau ofcials. We randomly selected 20 companies from the economic and technology development zone in each city (220 in total). To be included in the sample, the rms also needed to have been created within 10 years of our data collection in 2006. Among the nal 150 companies we physically approached, distributed surveys and conducted interviews, 130 survey packages were returned (86.7%) and 103 of all returned parts of the surveys were usable. Out of the initial contact, the nal response rate was 47% (103/220). No signicant differences were found between these rms and non-responding rms with regard to size and age.

Measures Performance management and career development were each measured with four items adapted from Verburg et al. (1999) and Wang and Zang (2005). A ve-point Likert scale was used to measure the degree of practices. A sample item for performance management was periodic performance appraisal activity and an item for career development was periodic internal employee position transfer. The Cronbach alphas were .90 and .84 for performance management and career development, respectively. A four-factor measurement of strategic entrepreneurship was designed on the basis of previous literature (e.g., Ireland, Hitt and Simon 2003), in-depth interviews, and prior research adapted to the Chinese situation (Wang and Zang 2005). A ve-point Likert scale was used (1 very uncharacteristic and 5 very characteristic). These four factors were: adaptive capability; resourceful innovation; proactive change; and risk anticipation. These four factors were rst tested among 10 companies through in-depth interviews and pilot surveys and the Cronbach alphas in the pilot test were .84, .80, .84, and .75, respectively. In the main study, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factoring using oblique rotation (Direct Oblimin) on the 18-item strategic entrepreneurship scale. Oblique rotation allows intercorrelations among factors. The results revealed four factors. These factors had eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and explained 67.58% of the total variance. Table 1 presents the rotated factor loadings for this four-factor structure. The Cronbach alphas were .90, .90, .86, and .75 for adaptive capability, resourceful innovation, proactive change and risk anticipation, respectively. In the strategic entrepreneurship survey, respondents were asked to identify in which city their rms were located, i.e. in which region they were situated. We coded participating rms into three groups (i.e., eastern, western, and central regions). Two dummy variables with the reference of eastern region were then created based on the location of the city to represent Chinas western and central regions. A survey of organizational performance was adapted from Wang and Satow (1994) and measured the following three indicators using ve-point Likert scale: . Market share: How much market share is held by the company compared with other companies in its industrial sector? (1 getting smaller, 2 expanding little, 3 expanding relatively little, 4 expanding fast, 5 expanding very fast)

952

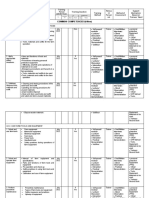

Table 1.

Strategic entrepreneurship factor analysis and factor loadings (oblique rotation). Resourceful innovation Risk anticipation .12 2.07 2.10 .07 2.09 .88 .80 2.11 2.11 .09 .07 .04 .04 2.12 .06 2.08 .04 .18 1.84 (10.22%) Adaptive capability .05 .28 .23 2 .04 .13 2 .10 .05 .82 .82 .81 .74 .63 2 .13 2 .18 .13 .36 .22 .21 1.47 (8.16%) Proactive change 2 .09 .07 .01 2 .15 2 .19 .12 2 .13 2 .04 2 .11 .14 2 .04 2 .13 2 .76 2 .72 2 .67 2 .61 2 .59 2 .49 1.18 (6.55%)

1. The rm sets up rewards for entrepreneurship and creative invention. 2. The rm establishes relevant systems to obtain innovative ideas from employees. 3. The rm sets up procedures to evaluate innovative ideas. 4. The rm sets up formal honorary titles for creative, excellent employees. 5. The rm provides effective resources to test new projects. 6. The rm anticipates challenges and risks in raising funds. 7. The rm anticipates high risk in expanding its market. 8. The rm facilitates new entrepreneurial activities through increasing autonomy of the departments. 9. The rm exibly adjusts organizational structure in order to strengthen entrepreneurial capability. 10. The rm coordinates departments to enhance entrepreneurial capability. 11. The rm adopts various approaches to change into new values, learn new knowledge and technology. 12. The rm organizes and adjusts new departments to enhance innovation and business development 13. The rm adopts strategic change according to competitive environment. 14. The rm plays a change leadership role rather than follower role. 15. The rm actively expands and takes risks in business. 16. The rm adopts proactive strategy in market competition. 17. The rm tries to adopt new strategies to cope with competitors. 18. The rm demonstrates technology change leading roles. Eigenvalues (variance explained)

.86 .77 .76 .74 .58 .09 2 .05 .04 2 .01 .19 .11 .26 .21 .19 .09 2 .08 .18 2 .22 7.68 (42.66%)

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

953

. Protability: How protable is this company in comparison with other companies in its industrial sector? (1 decit, 2 small prot, 3 middle level, 4 relatively protable, 5 very protable) . Competitiveness: How competitive is this company in comparison with other companies in its industrial sector? (1 very weak, 2 relatively weak, 3 middle level, 4 relatively strong, 5 very strong). Recognizing the limitations of one-item scales, we took the following steps. The indicators of organizational performance were rated by members of top management. For each indicator, we used the average of their ratings in each company based on the acceptable level of intraclass correlation (ICC) coefcients. To check reliability and validity, these indicators were also independently rated by industrial bureau ofcials. These ratings and the average ratings by top management team members were highly correlated, with an average correlation of .86, suggesting high reliability of the ratings. Control variables We included controls for several variables that may affect organizational performance. All these control variables were measured in the strategic entrepreneurship survey. First, we controlled for rm size as measured by the number of full-time employees because larger rms tend to have superior resources compared to smaller rms (Collins and Clark 2003). Specically, we used ve categories (, 50 scored 1; 50 100 scored 2; 100 500 scored 3; 500 1000 scored 4; and . 1000 scored 5). Second, ownership has been found to be related to rm performance in China (e.g., Peng and Luo 2000; Xu, Pan, Wu and Yim 2006). This variable was measured as state-owned rms (scored 1), privately-owned rms (scored 2), and foreign-invested rms (scored 3). Third, because rms with different developmental phases face fundamentally different problems and have different strategic focuses/goals which may affect their strategies and performance at the time (e.g., Kazanjian, 1988; Randolph, Sapienza and Watson1991), we also controlled for organizational phase. It was measured by (1) start-up phase, (2) growth phase, (3) maturity phase and (4) transformation phase.

Analysis strategy Hierarchical Ordinary Least Square (OLS) regression was used to test our hypotheses. Control variables were entered in the rst step followed by the two HRM practices (performance management and career development), dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship and the regions. In the last step, we included the interaction terms to test moderation effects. The variables, performance management, career development, and adaptive capabilities were entered before product terms were created (Cohen, Cohen, Western and Aiken 2003). Due to the relative small sample size and multicollinearity concern, we included one set of interaction terms at a time. Results Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables used in the study. An average rm in our sample had between 500 to 1000 employees. Table 3 reports the results of hierarchical regression analyses used to examine the effect of strategic entrepreneurship, HRM practices, and regions on organizational performance.

954

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

HRM practices Hypotheses 1 and 2 predicted that performance management and career development would be positively related to organizational performance. Regression results showed that performance management had signicant positive effects on all three indicators of organizational performance, competitiveness (b .35, p , .01), protability (b .28, p , .01), and market share (b .24, p , .05), providing support for Hypothesis 1. Contrary to our hypothesis, career development was negatively related to competitiveness at a marginally signicant level (b 2 .21, p , .10). No signicant effect was found for career development with regard to protability and market share. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was not supported. Strategic entrepreneurship Hypotheses 3a to 3d predicted positive relationships between dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship and organizational performance. As shown in Table 3, proactive change and risk anticipation had signicant effects on all three performance indicators including competitiveness, protability, and market share while adaptive capability and resourceful innovation were not signicantly related to any of these performance indicators. Specically, rms with higher levels of proactive change focus had higher competitiveness (b .51, p , .01), protability (b .24, p , .05), and market share (b .40, p , .01). On the other hand, unexpectedly, rms which anticipated greater risk had lower competitiveness (b 2 .25, p , .01) and protability (b 2 .37, p , .01). Therefore, Hypothesis 3c was supported while Hypothesis 3a, 3b and 3d were not. Hypothesis 3e predicted a moderating effect of adaptive capability on the HRM practices performance relationship. The results showed a signicant positive moderation effect (b .22, p , .05) of performance management on the adaptive capability competitiveness relationship and a negative moderation effect (b 2 .25, p , .01) of career management on the adaptive capability competitiveness relationship. No moderation effects were found for protability and market share. The pattern indicated in Figure 2 was consistent with our prediction. That is, the relationship between performance management and competitiveness was stronger, with a higher level of adaptive capability. However, the pattern in Figure 3 was the opposite of our prediction, suggesting the career development competitiveness relationship was stronger with a low level of adaptive capability. Therefore, Hypothesis 3e was partially supported. Regions Hypothesis 4 and 5 predicted the moderating effects of regions on the relationship between performance management and rm performance and between career development and rm performance, respectively. The results showed an interaction effect between performance management and western region (b 2 .31, p , .01) on competitiveness, and between performance management and central region on both competitiveness (b 2 .43, p , .01) and protability (b 2 .27, p , .01). A post-hoc analysis showed no difference between rms in the central region versus those in the western region with regard to performance management competitiveness relationship and performance management protability relationship. The patterns indicated in Figure 4 and 5 were consistent with those hypothesized. That is, there was a stronger relationship between performance management and competitiveness for rms located in the eastern region than those in the western and central regions; there was a stronger relationship between

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Table 2. Variables

Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables. M 2.52 1.67 3.55 .45 .21 3.69 3.22 3.69 3.03 3.59 3.06 3.63 3.16 3.51 SD .79 .71 1.35 .50 .41 .65 .85 .61 .74 .88 .77 .71 1.05 .87 1 2 .07 2 .02 2 .15 2 .06 .05 .10 2 .03 .13 .09 2 .07 2 .16 2 .05 2 .16 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

1. Phase 2. Ownership 3. Firm size 4. Eastern region 5. Western region 6. Adaptive capability 7. Resourceful innovation 8. Proactive change 9. Risk anticipation 10. Performance management 11. Career development 12. Competitiveness 13. Protability 14. Market share

2.22 .11 2.07 2.06 2.06 2.03 2.09 .15 .19 .11 2.07 2.21

.15 2 .13 .22 .46 .40 2 .13 2 .06 2 .14 .22 .26 .38

2.47 .13 .18 .18 2.18 .11 .30 .21 .14 .29

2 .09 2 .19 2 .18 .06 .03 2 .12 2 .18 2 .11 2 .20

.63 .60 2 .03 .05 .32 .28 .20 .27

.62 2.10 .19 .29 .34 .27 .35

.06 .10 .24 .50 .29 .48

.12 2 .14 2 .26 2 .39 2 .18

.54 .31 .32 .25

.19 .24 .23

.63 .59

.63

Note: Correlations with absolute values greater than .20, p , .05; correlations with absolute values greater than .25, p , .01; two-tailed test. Regions were dummy-coded with middle region as reference. Phase: start-up phase (1), growth phase (2), maturity phase (3), transformation phase (4); ownership: state-owned (1), privately owned (2), foreign-invested (3); rm size: ,50 (1), 50100 (2), 100 500 (3), 500 1000 (4), .1000 (5).

955

956

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analyses for organizational performance. Competitiveness Protability DR2 .09* 2 .06 2 .10 .23* .38 .35** 2.21 .04 2.03 .51** 2.25** 2.13 2.03 .43 .22* 2.25** .47 2.31** 2.43** .37 2.01 2.11 .00 2 .03 2 .08 .09** 2 .05 2 .27* .27 .00 .05 .18 .06** .06 2 .07 .31 .03 .02 2.05 .40 .01 .36** .28** .05 .02 2 .07 .24* 2 .37** 2 .03 .06 .28 .01 .06 .02 .39 .00 .29 .29** .24* .05 2.02 2.07 .40** 2.13 2.17 2.09 .39 .00 b Adj.R2 .05 DR2 .08* 2.17 2.21* .32** b Market Share Adj.R2 .18 DR2 .21**

Independent variables Step 1 Phase Ownership Firm size Step 2 Performance management (PM) Career development (CD) Adaptive capability Resourceful innovation Proactive change Risk anticipation Western region Central region Step 3 PM * Adaptive capability CD * Adaptive capability Step 3 PM * Western PM * Central Step3 CD *Western CD * Central

b 2.14 .13 .25*

Adj.R2 .06

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

.40

.26**

Note: Standardized coefcients are reported. The interactions terms were included in the regression one set at a time in the last step of each equation. Adj.R2 Adjusted R2. p , .10, *p , .05, **p , .01, two-tailed test. Regions were dummy-coded with the Eastern region as the reference. N 103.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

957

Figure 2. The moderating effect of adaptive capability on the relationship between performance management and competitiveness.

performance management and protability for rms located in the eastern regions than those in the central region. No moderating effects of regions were found for the career development performance relationship. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was partially supported while Hypothesis 5 was not supported. Discussion This study examined the inuences of two important HRM practices and strategic entrepreneurship on rm performance and the moderating role of regions. The results revealed some interesting ndings. In this study, we used multiple informants from the same rm to complete different surveys. The main predictors measures in the study were conducted separately, including HRM survey among HR managers, strategic entrepreneurship survey among rm executives and performance survey among top managers. Therefore, the results of this study were less affected by biases such as common-method variance and individual bias.

Figure 3. The moderating effect of adaptive capability on the relationship between career development and competitiveness.

958

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

Figure 4. The moderating effect of regions on the relationship between performance management and competitiveness.

Consistent with prior research (e.g., Zahra and Covin 1995; Peng 2001), our results showed pursuing strategic entrepreneurship can lead to better organizational performance for newly established rms in economic and technological development zones in China. Specically, the results revealed four dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship: resourceful innovation; proactive change; risk anticipation; and adaptive capability. Among them, proactive change seems to be an inuential dimension that had a positive direct effect on organizational performance indicators while risk anticipation, unexpectedly, showed a negative effect on performance indicators. It seems the anticipation of risk and challenge becomes an obstacle for organizations to overcome the risks and pursue their goals. This suggests that entrepreneurial rms may sometimes benet from not spending too much time anticipating all possible risks and difculties that might lie ahead, but rather, they need to take some risks and focus on seizing opportunities and putting ideas into action, which is consistent with the concept of entrepreneurship (Ireland et al. 2003). Future research is needed to further examine this dimension. Although adaptive capability and resourceful innovation did not show direct effects on organizational performance, adaptive capability showed its potential as an important moderator as it inuenced the HRM practices performance relationships. It is also likely

Figure 5. The moderating effect of regions on the relationship between performance management and protability.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

959

that these strategic entrepreneurship dimensions may also interact with other resources and contextual factors to affect rm performance. Consistent with prior research that emphasizes the importance of HRM (e.g., Wright et al. 1994; Delaney and Huselid 1996; Huselid, Jackson and Schuler 1997; Law et al. 2003), performance management was found to be positively related to organizational performance. The unique history of the Chinese labour and personnel management systems leads us to argue that performance management is one of the most important changes that need to be made as it contributes directly to rm performance in the Chinese context. However, we are by no means suggesting that other aspects of HRM are neglectable or not important but because of the Chinese tradition of harmony and the egalitarian mentality, the adoption of performance management may be a particular challenge for Chinese rms. It seems that while performance management has been a strategic HRM practice inuencing signicantly organizational performance and might be better integrated with strategic entrepreneurship at this stage, career development might rquire a longer time period in order to demonstrate its impact on performance. Further, rather unexpectedly, we found a negative relationship between career development and competitiveness at a marginally signicant level. One possible explanation is that career development might have resulted in high performers leaving for better external opportunities as they are better equipped to take the opportunities available. Indeed, Chow and Liu (2007) suggested that relatively high turnover rate could signicantly undermine the benets/value of employee development. More research is needed on this issue and a replication of this nding is desirable. It has been argued that the inuence of globalization is uneven on HRM across Asia-Pacic regions (Warner 2002). Due to location differences, rms in different regions in China may affect the adoption of HRM practices (e.g., Ding et al. 2000; Wei and Lau 2005). Our ndings showed that with the same level of HRM practices, their inuences on rm performance could vary depending on the different labour markets and policies across regions. Prior research tends to compare the coastal region against inland China but our ndings suggest that ner categorizations of regions may shed more insights. For example, the performance management protability relationship was not signicantly different between rms in the eastern and western region but a difference was found comparing those in the eastern and central region. This may indicate that through years of developmental strategies, the gap between the eastern and western regions is getting smaller while the central region was still left behind. Rather than looking at location differences, it might be more fruitful in the future to examine specic relevant issues that are different across regions, such as access to labour, concentration of foreign rms (Li 2004), and labour mobility rates (Schonberg 2007). Implications and limitations The results of this study have several important implications for modelling HRM strategies in different regions in China. First, performance management and career development are among the most important HRM practices in linking with strategic entrepreneurship to affect organizational performance in China. Our ndings suggest that performance management is critical to rms and by building adaptive capability, rms can better utilize and coordinate human resources to enhance their competitiveness. Second, strategic entrepreneurship including proactive change and risk anticipation should receive special attention as they showed direct relationship with rm performance. However, at the same time, some specic practices related to human resources may provide additional needed support to achieving the goals. Third, regional models of HRM strategies need

960

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

to be built in order to better understand and develop more strategic HRM approaches to t with local contingencies such as regional policies, labour markets and entrepreneurship. This has important implications for entrepreneurs who are interested in starting or continuing businesses in the different areas. There were some limitations that need to be mentioned. First, we adopted the methodology of using independent surveys to collect data from different sources, which alleviated the common method bias. However, in order to build more comprehensive regional models, more sites and regions need be taken into account and as a result, the sample size was relatively small. Second, cross-sectional design was used and this prevented us from making causality conclusions. Although we argued the impact of strategic entrepreneurship and HRM practices on performance, we cannot rule out the possibility that organizational performance might inuence choices of strategies and practices. Future research should be carried out using a longitudinal approach in order to test the causal relationship. Finally, we used perceptual measures of organizational performance and adopted external validation rating because we were not able to obtain objective measures. Although prior research has found positive relationship between objective and perceptual measures of performance (Dess and Robinson, 1984; Geringer and Hebert 1991), future research using objective measures is needed to provide more insights. Conclusions The main objective of this study was to test the effects of strategic entrepreneurship and HRM practices on organizational performance. Our results showed that among the four dimensions of strategic entrepreneurship, proactive change was critical in determining organizational performance while adaptive capability interacted with performance management and career development to affect performance. Risk anticipation was negatively related to performance. While performance management is crucial for rms, the performance management and performance relationship vary across regions.

Acknowledgement

The research work was supported by the NSF China Key Project (Grant No. 70732001) and the Ministry of Education China doctoral programme funds. We wish to thank the guest editor, Professor Malcolm Warner, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

References

Antoncic, B. (2006), Impacts of Diversication and Corporate Entrepreneurship Strategy Making on Growth and Protability: A Normative Model, Journal of Enterprising Culture, 14, 1, 4963. Atuahene-Gima, K., and Li, H. (2004), Strategic Decision Comprehensiveness and New Product Development Outcomes in New Technology Ventures, Academy of Management Journal, 47, 4, 583 597. Barney, J. (1991), Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage, Journal of Management, 17, 99120. Barney, J.B., and Wright, P.M. (1998), On Becoming a Strategic Partner: The Role of Human Resources in Gaining Competitive Advantage, Human Resource Management, 37, 1, 31 46. Blomstrom, M., and Kokko, A. (1998), Multinational Corporations and Spillovers, Journal of Economic Surveys, 12, 2, 131. Borch, O.-J., and Madsen, E. (2005), Adaptive Capability and Strategic Entrepreneurship: An Empirical Study of Innovative SMEs, in Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research, eds. S.A. Zahra, C.G. Brush, P. Davidsson, J.O. Fiet, P.G. Greene, R.T. Harrison, M. Lerner, C. Mason, D. Shepherd, J. Sohl, J. Wiklund and M. Wright Braintree, MA: Babson, p. 225.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

961

Bruton, G.D., and Rubanik, Y. (2002), Resources of the Firm, Russian High-technology Startups, and Firm Growth, Journal of Business Venturing, 17, 6, 553 576. Buckley, P.J., Clegg, J., and Wang, C. (2002), The Impact of Inward FDI on the Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Firms, Journal of International Business Studies, 33, 4, 637655. Carlson, D.S., Upton, N., and Seaman, S. (2006), The Impact of Human Resource Practices and Compensation Design on Performance: An Analysis of Family-owned SMEs, Journal of Small Business Management, 44, 4, 531543. Caves, R.E. (1996), Multinational Enterprise and Economic Analysis, New York: Cambridge University Press. Child, J. (1999), Management and Organizations in China: Key Trends and Issues, Hong Kong: Chinese Management Centre, University of Hong Kong. Chow, I.H. (2004), The Impact of Institutional Context on Human Resource Management in Three Chinese Societies, Employee Relations, 26, 6, 626642. Chow, I.H.-S., and Liu, S.S. (2007), Business Strategy, Organizational Culture, and Performance Outcomes in Chinas Technology Industry, Human Resource Planning, 30, 2, 47 55. Cohen, J., Cohen, P., Western, S.G., and Aiken, L.S. (2003), Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (3rd ed.), Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association. Collins, C.J., and Clark, K.D. (2003), Strategic Human Resource Practices, Top Management Team Social Networks, and Firm Performance: The Role of Human Resource Practices in Creating Organizational Competitive Advantage, Academy of Management Journal, 46, 740 751. Covin, J.G., Green, K.M., and Slevin, D.P. (2006), Strategic Process Effects on the Entrepreneurial Orientation Sales Growth Rate Relationship, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 30, 1, 5781. Daily, C., McDougall, P., Covin, J.G., and Dalton, D. (2002), Governance and Strategic Leadership in Entrepreneurial Firms, Journal of Management, 28, 387412. Delaney, J.T., and Huselid, M.A. (1996), The Impact of Human Resource Management Practices on Perceptions of Organizational Performance, Academy of Management Journal, 39, 949 969. Dess, G., and Robinson, D. (1984), Measuring Organizational Performance in the Absence of Objective Measures: The Case of the Privately Held Firm and Conglomerate Business Unit, Strategic Management Journal, 5, 265 273. Ding, D.Z., Akhtar, S., and Ge, G.L. (2006), Organizational Differences in Managerial Compensation and Benets in Chinese Firms, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17, 4, 693 715. Ding, D.Z., Goodall, K., and Warner, M. (2000), The End of the Iron Rice-bowl: Whither Chinese Human Resource Management? International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11, 2, 217 236. Geringer, M.J., and Hebert, L. (1991), Measuring Performance of International Joint Ventures, Journal of International Business Studies, 22, 249 263. Huselid, M.A., Jackson, S.E., and Schuler, R.S. (1997), Technical and Strategic Human Resource Management Effectiveness as Determinants of Firm Performance, Academy of Management Journal, 40, 171 188. Ireland, R.D., Hitt, M.A., and Sirmon, D.G. (2003), A Model of Strategic Entrepreneurship: The Construct and its Dimensions, Journal of Management, 29, 6, 963989. Johnson, S., and Van de Ven, A.H. (2002), A Framework for Entrepreneurial Strategy, in Strategic Entrepreneurship: Creating a New Mindset, eds. M.A. Hitt, R.D. Ireland, S.M. Camp and D.L. Sexton, Oxford, UK: Blackwell, pp. 66 86. Kazanjian, R.K. (1988), The Relation of Dominant Problems to Stage of Growth in Technology-based New Ventures, Academy of Management Journal, 31, 257 279. Law, K.S., Tse, D.K., and Zhou, N. (2003), Does Human Resource Management Matter in a Transitional Economy? China as an Example, Journal of International Business Studies, 34, 3, 255265. Li, S. (2004), Location and Performance of Foreign Firms in China, Management International Review, 44, 2, 151 169. Liu, A.Y., Li, S., and Gao, Y. (1999), Location, Location, Location, The China Business Review, MarchApril, 2025. Liu, S.S., Luo, X., and Shi, Y.-Z. (2003), Market-oriented Organizations in an Emerging Economy, Journal of Business Research, 56, 6, 481491. Luo, Y. (1995), Business Strategy, Market Structure, and Performance of International Joint Ventures: The Case of China, Management International Review, 35, 242 264. Luo, X., Zhou, L., and Liu, S.S. (2005), Entrepreneurial Firms in the Context of Chinas Transition Economy: An Integrative Framework and Empirical Examination, Journal of Business Research, 58, 3, 277 284. Mayo, A. (2000), The Role of Employee Development in the Growth of Intellectual Capital, Personnel Review, 29, 4, 521533. McCline, R.L., Bhat, S., and Baj, P. (2000), Opportunity Recognition: An Exploratory Investigation of a Component of the Entrepreneurial Process in the Context of the Health Care Industry, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25, 2, 81 94. McDonald, D., and Smith, A. (1995), A Proven Connection: Performance Management and Business Results, Compensation and Benets Review, 27, 1, 5962. Menguc, B., Auh, S., and Shih, E. (2007), Transformational Leadership and Market Orientation: Implications for the Implementation of Competitive Strategies and Business Unit Performance, Journal of Business Research, 60, 4, 314321.

962

Z.-M. Wang and S. Wang

Peng, M.W. (2001), How Entrepreneurs Create Wealth in Transition Economies, Academy of Management Executive, 15, 1, 95108. Peng, M.W., and Luo, Y. (2000), Managerial Ties and Firm Performance in a Transition Economy: The Nature of a Micromacro Link, Academy of Management Journal, 43, 486501. Porter, M.E. (1998), Clusters and the New Economics of Competition, Harvard Business Review, November December, 7790. Randolph, W.A., Sapienza, H.J., and Watson, M.A. (1991), Technology-structure Fit and Performance in Small Business: An Examination of the Moderating Effects of Organizational States, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 16, 1, 27 41. Rindova, V.P., and Kotha, S. (2001), Continuous Morphing: Competing through Dynamic Capabilities, Forms, and Functions, Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1263 1280. Rummler, G.A., and Brache, A.P. (1990), Improving Performance, San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Satow, T., and Wang, Z.M. (1994), Cultural and Organizational Factors in Human Resource Management in China and Japan: A Cross-cultural Socio-economic Perspective, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 9, 4, 311. Schonberg, U. (2007), Wage Growth Due to Human Capital Accumulation and Job Search: A Comparison between the United States and Germany, Industrial & Labour Relations Review, 60, 4, 562 586. Schuler, R.S., Fulkerson, J.R., and Dowling, P.J. (1991), Strategic Performance Measurement and Management in Multinational Corporations, Human Resource Management, 30, 3, 365 392. Siu, W.-S., and Liu, Z.-C. (2005), Marketing in Chinese Small and Medium enterprises (SMEs), The State of the Art in a Chinese Socialist Economy, Small Business Economics, 25, 333346. Sun, L.-Y., Aryee, S., and Law, K.S. (2007), High-performance Human Resource Practices, Citizenship Behavior, and Organizational Performance: A Relational Perspective, Academy of Management Journal, 50, 3, 558577. Tsui, A., and Lau, C.M. (2002), The Management of Enterprises in the Peoples Republic of China, Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Verburg, R.M., Drenth, P.J.D., Koopman, P.L., Van Muijen, J.J., and Wang, Z.M. (1999), Managing Human Resources across Cultures: A Comparative Analysis of Practices in Industrial Enterprises in China and The Netherlands, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10, 3, 391410. Wang, C.L., and Ahmed, P.K. (2007), Dynamic Capabilities: A Review and Research Agenda, International Journal of Management Reviews, 9, 1, 3152. Wang, Z.M. (2006), Leadership Competency and Implicit Assessment Modeling, address at Congress Proceedings: XVIII International Congress of Psychology, Beijing 2004. Hove & New York: Psychology Press. Wang, Z.M., and Mobley, W. (1999), Strategic Human Resource Management for Twenty-rst-century China, in Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, eds. P.M. Wright, L.D. Dyer, J.W. Boudreau and G.T. Milkovich, London: JAI Press Inc, pp. 353 366. Wang, Z.M., and Satow, T. (1994), Leadership Styles and Organizational Effectiveness in ChineseJapanese Joint Ventures, Journal of Managerial Psychology, 9, 4, 3136. Wang, Z.M., and Zang, Z. (2005), Strategic Human Resources, Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fit: A Cross-regional Comparative Model, International Journal of Manpower, 26, 6, 544 559. Warner, M. (1999), Human Resources and Management in Chinas Hi-tech Revolution: A Study of Selected Computer Hardware, Software and Related Firms in the PRC, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 10, 1, 120. Warner, M. (2002), Globalization, Labour Market and Human Resources in Asia-Pacic Economics: An Overview, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13, 384 398. Wei, L.-Q., and Lau, C.-M. (2005), Market Orientation, HRM Importance and Competency: Determinants of Strategic HRM in Chinese Firms, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16, 19011918. White, S. (2000), Competition, Capabilities, and the Make, Buy, or Ally Decisions of Chinese State-owned Forms, Academy of Management Journal, 43, 324341. Wright, P.M., and Barney, J. (1998), On Becoming a Strategic Partner: The Role of Human Resources in Gaining Competitive Advantage, Human Resource Management, 37, 1, 31 46. Wright, P.M., McMahan, G.C., and McWilliams, A. (1994), Human Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage: A Resource-based Perspective, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 5, 301 326. Xu, D., Pan, Y., Wu, C., and Yim, B. (2006), Performance of Domestic and Foreign-Invested Enterprises in China, Journal of World Business, 41, 3, 261274. Yang, K.M. (2002), Double Entrepreneurship in Chinas Economic Reform: An Analytic Framework, Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 30, 1, 134147. Zahra, S.A. (1991), Predictors and Financial Outcomes of Corporate Entrepreneurship: An Exploratory Study, Journal of Business Venturing, 6, 4, 259 285. Zahra, S.A., Brush, C.G., Davidsson, P., Fiet, J.O., Greene, P.G., Harrison, R.T, Lerner, M., Mason, C., Shepherd, D., Sohl, J., Wiklund, J., and Wright, M. (2005), Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 2005, Braintree, MA: Babson.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

963

Zahra, S.A., and Covin, J.G. (1995), Contextual Inuences on the Corporate Entrepreneurshipperformance Relationship: A Longitudinal Analysis, Journal of Business Venturing, 10, 4358. Zahra, S.A., Jennings, D.F., and Kuratko, D.F. (1999), The Antecedents and Consequences of Firm-level Entrepreneurship: The State of the Field, Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, 5, 4565. Zhou, L., Wu, W.-P., and Luo, X. (2007), Internationalization and the Performance of Born-global SMEs: The Mediating Role of Social Networks, Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 4, 673 690. Zhu, C.J. (2005), Human Resource Management in China: Past, Current and Future HR Practices in the Industrial Sector, London: Routledge.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 2013-IJHRM-strategic Integration of HRMDokument18 Seiten2013-IJHRM-strategic Integration of HRM2305060330Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management and Enterprise Performance in Small and Medium Enterprise in ChinaDokument39 SeitenHuman Resource Management and Enterprise Performance in Small and Medium Enterprise in ChinaIma KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yongmei Performance in SO Banking IndustryDokument24 SeitenYongmei Performance in SO Banking IndustryAshish Anand TripathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lee 20et 20al. 20 (2010)Dokument23 SeitenLee 20et 20al. 20 (2010)sajidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Human Resource ManagementDokument6 SeitenImpact of Human Resource ManagementIjaz Bokhari100% (1)

- HRM and Innovation StrategyDokument25 SeitenHRM and Innovation StrategySri KanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Human Resource Management PraDokument16 SeitenEffects of Human Resource Management Prasurya pratap singhNoch keine Bewertungen

- 305-Article Text-980-1-10-20190531Dokument14 Seiten305-Article Text-980-1-10-20190531eumague.136515090273Noch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management Practices and Firm Performance Improvement in Dhaka Export Processing ZoneDokument25 SeitenHuman Resource Management Practices and Firm Performance Improvement in Dhaka Export Processing ZoneGerishom Wafula ManaseNoch keine Bewertungen

- ITC - Balanced ScorecardDokument16 SeitenITC - Balanced ScorecardBibha Jha Mishra100% (1)

- Employee GreivanceDokument26 SeitenEmployee GreivanceMarutiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Links Between Business Strategy and Human Resource Management Strategy in Select Indian Banks: An Empirical StudyDokument19 SeitenLinks Between Business Strategy and Human Resource Management Strategy in Select Indian Banks: An Empirical StudychecklogsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Human Resource-Related Quality Management Practices IDokument42 SeitenThe Role of Human Resource-Related Quality Management Practices Iamreenshk73Noch keine Bewertungen

- Business Strategy and HRMDokument19 SeitenBusiness Strategy and HRMarchanam123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of Strategic Planning and Work Performance and Productivity of Employees in The Provincial Government of Misamis OccidentalDokument49 SeitenEffectiveness of Strategic Planning and Work Performance and Productivity of Employees in The Provincial Government of Misamis OccidentalJanet BarreraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management in The Afghanistan GovernmentDokument7 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management in The Afghanistan GovernmentAhmad Fawad FerdowsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross Cultural HRM IssuesDokument23 SeitenCross Cultural HRM IssuesShahriar MustafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Transformational and Ethical Leadership On Project SuccessDokument3 SeitenThe Role of Transformational and Ethical Leadership On Project SuccessAsadullah NiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Measurement: A Balanced Scorecard ApproachDokument5 SeitenHuman Resource Measurement: A Balanced Scorecard ApproachAngga Muhammad KurniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Changing Role of The Corporate HR Function in Global Organizations of The Twenty-First CenturyDokument19 SeitenThe Changing Role of The Corporate HR Function in Global Organizations of The Twenty-First CenturyPrakhar SahayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Change Drivers in Business Context: Evidence From PakistanDokument14 SeitenThe Change Drivers in Business Context: Evidence From PakistanVishal KalathiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource ProposalDokument42 SeitenHuman Resource ProposalMungujakisa MorphatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding Critical Success and Failure Factors of Business Process ReengineeringDokument10 SeitenUnderstanding Critical Success and Failure Factors of Business Process ReengineeringAndre RiantiarnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resources: A New Source For Competitive Advantage in The Global ArenaDokument17 SeitenStrategic Human Resources: A New Source For Competitive Advantage in The Global ArenaPMVC06Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Human Resource Management Practices and Business Strategies On Organizational PerformanceDokument63 SeitenThe Effect of Human Resource Management Practices and Business Strategies On Organizational PerformanceDiMA ArankiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Strategic HRMDokument6 SeitenLiterature Review On Strategic HRMtog0filih1h2100% (1)

- Managing Innovative Strategic HRMitcDokument14 SeitenManaging Innovative Strategic HRMitcshrennyshreyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Human Resources Management On Employee Performance: Organizational Commitment Mediator VariableDokument17 SeitenThe Impact of Human Resources Management On Employee Performance: Organizational Commitment Mediator VariableEnrique ImNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Transformational Leadership, Organisational Learning and Technological Innovation On Strategic Management Accounting in Thailand's Financial InstitutionsDokument24 SeitenEffects of Transformational Leadership, Organisational Learning and Technological Innovation On Strategic Management Accounting in Thailand's Financial InstitutionsdiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Human Resource Management On Organizational PerformanceDokument11 SeitenThe Impact of Human Resource Management On Organizational PerformanceAayush KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Human Resource Management On Organizational PerformanceDokument11 SeitenThe Impact of Human Resource Management On Organizational PerformanceAayush KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Innovation Not Imitation: Human Resource Strategy and The Impact On World-Class StatusDokument9 SeitenInnovation Not Imitation: Human Resource Strategy and The Impact On World-Class StatusCamilo QuevedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Literature Review On Contingency Factors and Bank Performance in ChinaDokument10 SeitenStrategic Literature Review On Contingency Factors and Bank Performance in ChinaThe IjbmtNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM BookDokument20 SeitenHRM BookMihir GhaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Practices and Organizational Performance. Incentives As ModeratorDokument16 SeitenHuman Resource Practices and Organizational Performance. Incentives As ModeratorNaeem HayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linkage Between Human Resource Management Practices and PerformanceDokument12 SeitenLinkage Between Human Resource Management Practices and PerformanceRavi KumawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Senior Manager's Perception About HRM in MalaysiaDokument6 SeitenSenior Manager's Perception About HRM in MalaysiaAli AghapourNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Literature Review-Systematic Approach: Mostly Discussed Research Areas in Human Resource Management (HRM)Dokument13 SeitenA Literature Review-Systematic Approach: Mostly Discussed Research Areas in Human Resource Management (HRM)asmita_matrix1983Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Study of Perception and Challenges Faced by HRM Function in PakistanDokument10 SeitenA Study of Perception and Challenges Faced by HRM Function in PakistanMuhammadMansoorGoharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management in Multinational Corporations: Prakriti Dasgupta, Ronan Carbery and Anthony McdonnellDokument20 SeitenHuman Resource Management in Multinational Corporations: Prakriti Dasgupta, Ronan Carbery and Anthony McdonnellM SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management SHRMDokument8 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management SHRMIndah ZaharaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HR Roles Effectiveness and HR Contributions Effectiveness: Comparing Evidence From HR and Line ManagersDokument6 SeitenHR Roles Effectiveness and HR Contributions Effectiveness: Comparing Evidence From HR and Line ManagersGanesh ChhetriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soomro, R. B., Gilal, R. G., & Jatoi, M. M. (2011)Dokument14 SeitenSoomro, R. B., Gilal, R. G., & Jatoi, M. M. (2011)Azra Farrah Irdayu AzmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Management Journal PDFDokument21 SeitenStrategic Management Journal PDFselvyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review Human Resources ManagementDokument5 SeitenLiterature Review Human Resources Managementauhavmpif100% (1)

- Determinants of Strategic Plan Implementation in OrganizationsDokument12 SeitenDeterminants of Strategic Plan Implementation in OrganizationsyaredgirmaworkuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding The HRM-Performance Link: A Literature Review On The HRM Strategy Formulation ProcessDokument11 SeitenUnderstanding The HRM-Performance Link: A Literature Review On The HRM Strategy Formulation ProcessBoonaa Sikkoo MandooNoch keine Bewertungen

- Análisis de Trabajo, Una Práctica Estratégica de Gestión de Recursos HumanosDokument27 SeitenAnálisis de Trabajo, Una Práctica Estratégica de Gestión de Recursos Humanosliz LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHRM PDFDokument8 SeitenSHRM PDFKaran UppalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Examples of Strategic Human Resources ManagementDokument3 SeitenExamples of Strategic Human Resources ManagementRichard ZawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of HR Practices On Employee PerformanceDokument19 SeitenImpact of HR Practices On Employee Performancelast islandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Behavior: A Case Study of Tata Consultancy Services: Organizational BehaviourVon EverandOrganizational Behavior: A Case Study of Tata Consultancy Services: Organizational BehaviourNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM Employee RetentionDokument14 SeitenHRM Employee RetentionKalbe HaiderNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationship Among Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning, and Organizational PerformanceDokument13 SeitenThe Relationship Among Knowledge Management, Organizational Learning, and Organizational PerformanceReema KapoorNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Nestlé Human Resources PolicyDokument24 SeitenThe Nestlé Human Resources Policyamanpreet0% (1)

- Current Pms PracticesDokument11 SeitenCurrent Pms PracticesAMRITANSH AGRAWALNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hitt - Strategic ManagementDokument7 SeitenHitt - Strategic ManagementFernando R SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of High Performance Work SysDokument16 SeitenThe Effects of High Performance Work SyssabaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Marketing Planning SMP and Sme PDFDokument13 SeitenStrategic Marketing Planning SMP and Sme PDFmaleeha mushtaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Masters of Business Administration (Mba) : Project Report On Live Projects On Non-Governmental Organization (Ngos)Dokument15 SeitenMasters of Business Administration (Mba) : Project Report On Live Projects On Non-Governmental Organization (Ngos)Virat SilswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Askari Commercial BankDokument42 SeitenIntroduction To Askari Commercial BankMajid Yaseen0% (1)

- Rewards Practices PDFDokument14 SeitenRewards Practices PDFJahanzeb ShahNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV ATS Mauriska Dearsi Ayanda (English)Dokument2 SeitenCV ATS Mauriska Dearsi Ayanda (English)mauriska dearsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LAD 5182 Introduction To Office & Personnel Management of Legal FirmsDokument15 SeitenLAD 5182 Introduction To Office & Personnel Management of Legal FirmssyakirahNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Analysis of Employee RecognitionDokument16 SeitenAn Analysis of Employee RecognitionPasquimelNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Reg SitesDokument6 SeitenCV Reg SitesFida HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alcon CablesDokument63 SeitenAlcon CablesMT RANoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM Case StudyDokument4 SeitenHRM Case StudyAyesha YounusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hacking The Future of HRDokument64 SeitenHacking The Future of HRNindyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Determinants of Pakistan Foreign PolicyDokument5 SeitenDeterminants of Pakistan Foreign Policyusama aslam56% (9)

- Roles of A Human Resource ManagerDokument19 SeitenRoles of A Human Resource ManagerKharim BeineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Henry FayolDokument9 SeitenHenry Fayolmanojtandale100% (1)

- Ne Ev BrochureDokument16 SeitenNe Ev Brochurex1y2z3a1Noch keine Bewertungen

- HRM in Co-Operative BankDokument10 SeitenHRM in Co-Operative BankDivya RangarajNoch keine Bewertungen

- GB520 Unit 3 Case AnalysisDokument9 SeitenGB520 Unit 3 Case AnalysisKatherine Moore GageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Profile Options in Oracle HRMSDokument9 SeitenProfile Options in Oracle HRMSRajiv ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Human Resources Cloud Implementing Global Human Resources@@@Dokument648 SeitenGlobal Human Resources Cloud Implementing Global Human Resources@@@hamdy2001Noch keine Bewertungen

- Oap TP CommonDokument4 SeitenOap TP CommonBautista PalalayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resourse Management: Team MemberDokument41 SeitenHuman Resourse Management: Team MemberLogesh UmapathiNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Empirical Study On Recruitment and Selection Process With Reference To Private Universities in UttarakhandDokument20 SeitenAn Empirical Study On Recruitment and Selection Process With Reference To Private Universities in UttarakhandsuryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The SHRM HRBP Training & DevelopmentDokument132 SeitenThe SHRM HRBP Training & Developmentara coNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Understanding HRMDokument12 SeitenChapter 1 Understanding HRMFadhlan FadhilahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resou RceDokument450 SeitenHuman Resou Rcejas12321100% (1)

- Fundamentals of business management-thầy Bản - 231025 - 150423Dokument50 SeitenFundamentals of business management-thầy Bản - 231025 - 150423Trần Ngọc Bảo TrânNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Overview of Human Resource Management: MoneyDokument191 SeitenAn Overview of Human Resource Management: Moneymelkamu endaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management Contemporary IssuesDokument599 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management Contemporary IssuesNaqash Jutt100% (15)

- Assignment 3 HRM2Dokument21 SeitenAssignment 3 HRM2Fasih Khairi67% (3)

- Functions of The Human Resource DepartmentDokument4 SeitenFunctions of The Human Resource DepartmentT YungNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2024 UAE Salary GuideDokument30 Seiten2024 UAE Salary Guideabdelrahman.m.youssefNoch keine Bewertungen