Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Educational Complex Kelley

Hochgeladen von

temporarysite_orgOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Educational Complex Kelley

Hochgeladen von

temporarysite_orgCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mike Kelley. Educational Complex. 1995. Photograph by Gran rtegren.

The Educational Complex: Mike Kelleys Cultural Studies

HOWARD SINGERMAN

I. First shown at New Yorks Metro Pictures in 1995 and now in the Whitney Museums collection, Mike Kelleys Educational Complex is a set of architectural models, realized with the help of professional architects, in foam core, berglass, and wood; its platform is some sixteen feet long by eight feet across. Its a work I think is very smart, for reasons I hope will become clear in the following pages, but I will begin with its title, and the way its second word, complex, nods to both the psychological, as in Oedipus, and the institutional, as in military-industrial. The models recreate each of the buildings in which Kelley was reared, educated, and disciplined, from his family home in Westland, Michigan, a suburb of Detroit, where he was born in 1954, to the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia (CalArts), where he received his MFA in 1979. The models are something of a record of his coming of ageof his becoming something, at leastbut the passage is far from transparent and the terms of its re-creation murky. It is crossed from the outset, rather deliberately, by the failures of memory and the constructions of ction. Kelley has talked about the making of Educational Complex and related pieces in numerous statements and interviews. More than once he has explained that its autobiographical thrust was a direct response to his dissatisfaction with the way in which his work of the mid- to late 1980sthe thrift-store afghans, the stuffed animals, and the felt bannershad been misread. He was dismayed with the assumption that the work was quite specically and sadly about him, about his childhood and some putative trauma or abuse. He complained to Dennis Cooper in an interview in Artforum that people really started to free-associate

* Versions of this paper were delivered at the Princeton University Art and Archaeology Graduate Student Conference; the Institut fr Kunstgeschichte, Universitt Bern; the graduate studio art program of the University of Southern California; and the California Institute of the Arts. My thanks to those audiences of students and teachers for their comments, and to Hal Foster, Lane Relyea, Sande Cohen, and George Dimock for comments on the manuscript. OCTOBER 126, Fall 2008, pp. 4468. 2008 October Magazine, Ltd. and Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

46

OCTOBER

around those materialsaround that yarn and feltand to project all sorts of things onto my own biography. It made me really, really unhappy that no matter what I did with those materials, thats all people could talk about . . . . I knew that on one level they evoked childhood and all that, but I also thought they were about class aesthetics and formal things that were going on and things about categorization. Over six years, I did a number of different shows that really focused on different aspects of those kinds of materials, and yet the critical reception always tended to be about nostalgia and trauma. I nally got so pissed off about this that I just said, Ill give people what they want. I invented this pseudobiography and started doing biographical work. That was Educational Complex.1 Educational Complex and its related works are, as Kelley says, pseudobiography, but they are also, in ways I hope to present, quite accurate, or as Kelley himself put it: Despite the fact that my biography might be fabricated, its not ahistorical.2 Kelley had originally intended to construct these models based on plans drawn from memory. But his recollections were too incomplete: the drawings simply did not provide enough information to build three-dimensional structures.3 As realized, Educational Complexs external elevations are fairly accurate; Kelley ended up basing them on photographs and site visits, but the insides remain structured by memory: they record both what he could rememberwhether accurate or notand what had been forgotten. The rooms and hallways, the interiors that Kelley could not remember are not left empty; rather they are represented by solid, inaccessible blocks, as though his inability to remember signied something else, something repressed. As he put it in the title of an essay published in Architecture New York in 1996, architectural non-memory [is] replaced with psychic reality.4 Kelley took his inability to remember seriously, or it might be more accurate to say, symptomatically. His methodological touchstone was repressed memory syndromeor sometimes retrieved or even false memory syndrome, a topic of widespread public discussion (and of media-driven hysteria) in the 1980s and 1990s. On the surface, Educational Complex seems far from hysterical, but as Kelley told Cooper, It doesnt say on the surface of this work that its about repressed-memory syndrome. It doesnt have to. That's part of the way everyone looks at everything anyway.5 Certainly, at a certain moment, it seemed to be. In Los Angeles, repressed

1. Trauma Club: Dennis Cooper Talks with Mike Kelley, Artforum 39, no. 2 (October 2000), pp. 12429. 2. Interview: Isabelle Graw in conversation with Mike Kelley, in Mike Kelley, with contributions by John C. Welchman, Isabelle Graw, and Anthony Vidler (London: Phaidon, 1999), p. 39. 3. Missing Space/Time: A Conversation between Mike Kelley, Kim Colin, and Mark Stiles, in Mike Kelley, Minor Histories: Statements, Conversations, Proposals, ed. John C. Welchman (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2004), p. 332. 4. Mike Kelley, Repressed Architectural Memory Replaced with Psychic Reality, ANY: Architecture New York, 15 (1996), pp. 3639. 5. Trauma Club, p. 129.

The Educational Complex

47

Kelley. The Wages of Sin (left) and More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid. Both 1987. Photograph by Douglas M. Parker.

memory syndrome gured most infamously in the 1980s in the McMartin Preschool case, where the alleged abuse was situated in a school building, precisely as its architecture was imagined, misconstrued, or misremembered. It is difcult to summarize the McMartin case, and difcult as well to catch its hysteria or its just believability. What began as a single accusation of child abuse in a Los Angeles day-care center in the summer of 1983 would grow by May of 1984 into the indictment of seven adults on 208 charges alleging the abuse of forty child victims. It ended nearly a decade later with the demolishing of the school building, the dismissal of all but two counts, and, nally, after two hung juries, not a single conviction. Like the Educational Complex, although certainly more horribly, the McMartin site was transformed into imaginary architecture, marked not by what was visible, but by what could not be seen, what could only be remembered or suggested. With the urging and assistance of various parents, prosecutors, and therapists, the McMartin children assembled increasingly detailed stories of sexual abuse, Satanic worship, and animal torture, and equally detailed maps of trapdoors, passages, and secret rooms under the preschools concrete slab, as though drawing a model of the unconscious itself, of repressed material seeking its way through the egos defenses. In March 1985, a group of fty McMartin parents attempted to excavate the site in search of

48

OCTOBER

the hidden architecture their children had described; a few days later, an archeological rm hired by the District Attorneys Ofce began its own dig. Authorities found no evidence of rooms or tunnels, but one can still nd dissidents writing essays on the Web insisting on their existence. What is crucial to them, it seems, and to the researchers and psychologists who interviewed the McMartin children over and over again in the 1980s and, indeed, to Mike Kelley in his architectural remembrancesis just that lack of evidence: the non-correspondence between exterior elevation and interior life. Against the clarity and transparency of modern educational architecture, and of the reasoned pedagogy it at once gures and Hans Hofmann. informs, they cling to a distinctly antimodEquinox. 1958. ernist, even gothic, darkness. But here I need to pull back a bit: the psychologists and researchers were all experts, licensed professionals, trained in just such buildings; and Kelley, for his part, insists that his complex is a fully modern, or at least fully formal, one. II. The buildings in Educational Complex are not arranged in chronological or biographical order; rather, as Kelley has explained in multiple places, the work is really a formal thing, a compositional exercise. This seems a little disingenuous, given not only the way everyone looks at everything anyway, but also the volatility of his sources. Still, it is the same assertion he made about the stuffed animals and felt banners, when he spoke of his disappointment with how they were received. They, you will recall, referenced class aesthetics and formal things that were going on and things about categorization. Perhaps what formal meantat least in that caseis something closer to semiotic, that is, that his thrift-store objects carry and produce fully social meanings, that they function culturally, rather than magically or personally: they open out ideologically to the way everyone looks at everything. Elsewhere he will insist that that is how he has always used symbols, how he has composed the objects and images he has appropriated since college . . . which is, to bring things back to cases, where he learned the means by which he has composedhas balanced and enframedthe edices here. According to Kelley, the buildings in Educational Complex are arranged in homage to Hans Hofmann, according to the masters theory of push-pull. It is composed, that is, in relation to the dynamic of the rectangle, at once situated in and constructing an improvisationally

The Educational Complex

49

Kelley. Educational Complex, viewed from above.

gridded order. In the model, I see the blocks of repressed space as formally analogous to the rectangular blocks of paint in some of Hofmanns paintings. In such paintings, unstructured organic paint application is balanced by the superimposit ion of geometr ic forms. 6 It is not just in it s represent at ions that Educational Complex is about Kelleys schooling, but in its method and its form. Kelley speaks about art school in two distinctly different ways. On one level, he is informatively mundane, and sometimes he is quite generous. He was an undergraduate art student at the University of Michigan from 1972 to 1976, where he recalls his training as quite academic with generous doses of color theory [taught according to an Albers-based formal approach7], life and still life drawing and painting, and even exercises in such archaic techniques as egg tempera painting and hand calligraphy. The typical student painting was a gestural abstract formalist composition in the Hans Hofmann manner.8 As dry as that sounds, Kelley writes warmly of a few of his old Ann Arbor teachers: Gerome Kamrowski, Al Mullen, and Jacqueline Rice. A ceramic sculptor, Rice was only briey at Michigan; she received her MFA in 1970 from the University of Washington (where the rst MFA degree was awarded in 1924), and left Ann Arbor for the Rhode Island School of Design just after Kelley graduated. Given the degree, her West Coast MFA, and, not coincidentally, her gender, Rice stands for a different kind of history than Kamrowskis and Mullensa newer, more American one. Their

6. 7. 8. Missing Space/Time, p. 329. Mike Kelley, The Poetry of Form, in Minor Histories, p. 96. Mike Kelley, Missing Time: Works on Paper 19741976, Reconsidered, in Minor Histories, p. 64.

50

OCTOBER

story is more familiarly embedded in a history of European modernism, and through them, as Timothy Martin has pointed out, Kelleys artistic upbringing can be linked to the three European migrs who most inuenced American postwar art educationJosef Albers, Hans Hofmann, and Lszl Moholy-Nagy.9 Kamrowski, in the 1920s, at the University of Minnesota, had been a student of Cameron Booth, one of Hofmanns earliest American followers, and he went on to study with Hofmann in New York and Provincetown, as well as with Moholy-Nagy in Chicago, at the New Bauhaus. Before leaving New York for Ann Arbor in 1946, Kamrowski was also part of a circle of artists around the Surrealist Roberto Matta, painting experimental canvases with Jackson Pollock and William Baziotes in 1940 and 1941. Mullen had studied with Fernand Lger in Paris just after World War II, and then with Hofmann in New York, where he experienced a brief moment of recognition as an Abstract Impressionist in the early 1950s, showing on and off into the 1960s. He taught at Michigan from 1956 until his death in 1983. Thus, Kelleys link to the European masters is, at least on paper, continuous, a matter of one degree of separation, but its not at all clear what that means, or, more to the point, what that meant to him then. How good was the reception in Ann Arbor? Here is a curious piece of evidence: the 1974 University of Michigan School of Art bulletin Kelley. Cottage Cheese. 197495. notes that both Kamrowski and Mullen were student s of Hofmann, but Hofmann is spelled incorrectly in both of the short biostwo fs and one nas if it named an imposter, or someone who mattered a long time ago. Introducing a series of paintings dated 197495, works such as Cottage Cheese, rst nished in Ann Arbor and then, as Kelley says, reconsidered, he writes of his teachers rather differently: I attempted to relearn to paint in the manner of my college years, and [have] presented the results as a form of art therapy meant to confront the institutional abuse of my academic formalist painting training.10 His accusation is quite pointed, as Martin notes: The cult leader or abuser in question is not merely the faceless institution of Kelleys art education, but the patriarch of the specic method behind his undergraduate instruction in painting: the venerable pedagogue Hans Hofmann.11 Kelley himself implicates the master; he names Hofmann directly, legally, as the involved party, lling in the blanks of a Suspected Child Abuse Report. Explain known history of similar incident(s) for this child, prompts the form: repeatedly, continually, over and over . . . now living in a frozen,

9. Timothy Martin, Abuse and Composition: Notes on Missing Time, in Mike Kelley 19851996, ed. Jos Lebrero Stals (Barcelona: Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, 1997), p. 84. 10. Mike Kelley, Black Out, in Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, p. 158. 11. Martin, Abuse and Composition, p. 84.

Kelley. Abuse Report. 1995.

52

OCTOBER

perpetual stasis. Time is uniform, classical, free of history, replies Kelly. He might be describing a certain formalism, but here it is one that belongs not to the surface of painting but to the timeless repetitions of his teachers, guys who had been teaching at Michigan since the war, telling their old war stories of the art world, not only to Kelley, but to legions of students, maybe even to the conceptual artist Douglas Huebler, Kelleys graduate school mentor at CalArts in the late 1970s, who had had the same teachers as an undergraduate at Michigan some twenty years earlier. Present location of the child, asks the form; Kelleys answer: he is dwelling in the past: painful and secure.12 Hofmann had denied all such charges, so to speak, nearly two years before Kelley was born: I consider it part of my artistic responsibility to help, support, and encourage always all that is young, vital, progressive, and honest.13 That is certainly the claim of a charismatic teacher, one involved in the lives of his students insofar as they areor are mistaken forthe life of art. Perhaps he has helped too much. Kelleys charge is that he has exercised undue inuence, that he has bent his students in particular ways, that he continues to haunt them. III. What does it mean to speak of inuence, even in the moreindeed the mostconventional sense? What sense exactly does it make to say that Kelley was inuenced by Hofmann, or Kamrowski, or Mullen, or for that matter by Huebler? Kelleys 1997 appreciation of his CalArts mentor is entitled, in full Oedipal cry, Shall We Kill Daddy. His charge is exaggerated, traumatized, but it is, I would argue, situated in the correct register. His map of repressions, of those sites within his art training that he cannot remember, that he cannot logically situate in the trajectory that the Educational Complex plots, suggests that there is a kind of blank at the center of artistic training. There is, to make this as obvious as possible, no clear path that goes from fullling assignments to being an artist. There is a point (a decidedly unpunctual one) where that training switches from the answering of assignmentscolor and design exercises out of Albers, perhaps; the standard procedures of a medium-based art education and the sorts of things that can be taught, practiced, and corrected against a standardto the demand, however buried, that one make ones own work. This is an increasingly opaque and unmappable transformation insofar as it is no longer obvious what it is necessary for an artist to know or what skills he or she must have, and whether the display of those skills is ever, any longer, enough to constitute the work of art. The scenario inscribes a moment of abandonment, at least perceived, on the part of the teacher, and, on the side of the student, of aggressivity and identication: Kelleys off-the-rack Oedipus isnt far offbut it is, in ways Ill try to make

12. Mike Kelley: The Thirteen Seasons (Heavy on the Winter), exh. cat. (Cologne: Jablonka Galerie, 1995). 13. Hans Hofmann, What is an Artist? address given at Forum 49, July 3, 1949, Provincetown, in Hans Hofmann, ed. Cynthia Goodman (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1990), p. 168.

The Educational Complex

53

clear, off-the-rack. Unfulllable, the assignment becomes a demand posed to the student as artist; its questionthat is, the question it raises in the studentis: He is saying this to me but what does he want? This is Jacques Lacans formula for the birth of desire in the child, but it could also describe the scene of professional desire.14 For Lacan, it is the childs unvoiced question to the parent, and to the enigma of the adults desire, but it is also, as I have noted elsewhere, the question the young San Francisco painter Ernest Briggs posed to his teacher Clyfford Still in the late 1940s, or, rather, in recollection, about him: he became a problem to me . . . in terms of, what does it mean? What does he mean?15 Mean to me, of course: how can I give him what he wants? Not what he asks for, but what he lacks, what he wont dismiss right off as sheer repetition, the same stuff students showed him ten years ago, or twenty, or more. Thus the scene of teaching is not quite so simple as Kelley has imagined it, or at least as he wrote of it in the liner notes that accompanied a three-CD set of his reunited college band, Destroy All Monsters: art school, despite its reputation for nonconformity, is just the same as any other academic practice. It breeds people who want to please rather than follow their own interests.16 At some point, I would argue, what pleases in this exchange, what situates itself in relation to what the teacher wants, is precisely the students interests as they stand, at least for the teacher, forin Hofmanns wordsall that is young, vital, progressive. Kelley himself describes the scenario: I . . . drew from my own knowledge of fringe popular culture: weird second-rate comic books, erotica, adolescent imagery, and my interest in the fringes of the art world and underground culture. For example, I included recognizable images of Patty Hearst, the Symbionese Liberation Army logo, Santo the Mexican masked wrestler, William Burroughs, Rudolph Schwarzkogler, Stravinsky, Sun Ra, etc., in my compositions, alongside more mundane or ridiculous images and various paint handling techniques to push what I considered the limits of equivalency.17 Kelleys list of images is indeed vital and progressive. He was a good student at Michigan, a successful undergraduate among the nearly 400 majors, perhaps because his interests succeeded in producing his youth and his difference as content. They answered to the teachers implicit demand: show me something I havent seen. Be interestingin order that I might once have been. Interesting is a term that has had signicant

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. 14. Alan Sheridan (New York: W.W. Norton, 1978), p. 214. Quoted in Howard Singerman, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University (Berkeley: 15. University of California Press, 1999), pp. 14647. Mike Kelley, Destroy All Monsters: Liner Notes for 3CD Box Set (extract), 1994, in Mike Kelley, 16. p. 120. 17. Mike Kelley, Missing Time: Works on Paper 19741976, Reconsidered, exh. cat. (Hannover: KestnerGesellschaft, 1995), n.p. The version that appears in Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, is cast slightly differently through this paragraph.

54

OCTOBER

play of late, following the possibility opened up in Donald Judds famous formulation, a work of art needs only to be interesting, and even more in Michael Frieds infamous attack on it.18 Defending Judd against Frieds dismissal, against the merely seemingly implied by interesting, various art historians have traced Judds interest back to the Pragmatist philosopher Ralph Barton Perry in a way that thickens, and, so to speak, dignies the term, that gives it an appropriate history. Here I want to keep it thin, and even thinner than the way Hal Foster has glossed it: the neo-avant-garde . . . [marks] an implicit shift from a disciplinary criterion of quality, judged in relation to artistic standards of the past, to an avant-gardist value of interest, provoked through a testing of cultural limits in the present.19 What I am after is something like the way that Scott Rothkopf used the word a few years ago, in a review of the 2004 Whitney Biennial: The lions share of this work seems to announce for its makers, I am interested in thiswith this preferably standing for some slightly outr yet hip cultural signier like Super Mario Bros. or a disco ballad your parents once knew.20 This sort of interest suggests not Judds specic object, situated in relation to an audience for art, nor, indeed, any sort of specicity; what it suggests instead is spread, as it opens out onto other cultural sites and other audiences. It connects us ready-made to a whole universe of meaning, as Rothkopf says, especially as that universe is peculiarly, interestingly different than our own. IV. Frieds and Fosters opposing terms, quality and interest, echo for me another, more parochial and bureaucratic opposition: a debate joined about a decade ago between the discipline of art history, on the one side, and the metonymically slippery, intertwined and interdisciplinary elds of visual culture, visual studies, and, sometimes, cultural studies, on the other.21 Posed against the boundaries and hierarchies of art history, they are characterized by horizontal spread, a thinned promiscuousness of methods and objectsof interests and subject matters. And here is where Kelleys interests and mine might coincide: the kinds of interests that Kelley had, or that distracted Rothkopf at the Whitney, raise the same questions around audience, appropriation, identication, and subculture that cultural studies has taken up. Lets

18. Donald Judd, Specic Objects, in Donald Judd: Complete Writings 19591975 (Halifax: Press of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1975), p. 184. Frieds critique is in Art and Objecthood, now included in his Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), see in particular pp. 16467. 19. Hal Foster, Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996), xi. 20. Scott Rothkopf, cited in Mary Leclre, From Specic Objects to Specic Subjects: Is there (still) Interest in Pluralism? Afterall, no. 11 (2005), p. 9. Leclres essay is a close reading of the word interest in relation to contemporary practice. 21. On the confusion of these terms and for a discussion of this debate as it appeared in October and elsewhere, see Marquard Smith, Visual Studies, or the Ossication of Thought, Journal of Visual Culture 4, no. 2 (2005), pp. 23756. Smith is concerned to clarify these terms; here, I take advantage of their conation.

The Educational Complex

55

say that Kelleys multiple undergraduate interests allow us to see that different audiences communicate within different structures of tradition, linguistic convention, and behavioral forms of interaction, and that specicity of audience address and experiences must be part of the study of culture. Im quoting from the synopsis of Stuart Halls and Raymond Williamss cultural studies that appears in the methodological introduction to the social history of art in the opening pages of Art Since 1900: Modernism, Anti-Modernism, Postmodernism, a survey text authored by Foster with Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin Buchloh, all editors of this journal. (Let me start this turn by saying that I will rely on Art Since 1900 a few more times in the coming pages, not because of its links to October, but because of its links to the classroom and the scene of teachinglinks legible in its synoptic methodological introductions, its glossary, and its sidebars; the classroom is, after all, where most of this essay takes place.) The authors conclude their brief on cultural studies by allowing Theodor Adorno to comment on it, or, rather, by imagining what Adornos comment would have been, given Halls and Williamss refusal of the hierarchical and hegemonic singularity of culture. Speaking as Adorno, they introduce yet another concept: Adornos counterargument would undoubtedly have been to accuse their project of being one of extending desublimation into the very center of aesthetic experience, its conception and critical evaluation.22 I have wanted to get to desublimation for some timethose familiar with Kelleys work might think that I have taken a very long way around. Ive taken this path so that I can go through the question of cultural studies, and put that on the table as well, because I am not sure how the work of desublimation works for Kelley, or for any artist anymore. The glossary in Art Since 1900 takes a serious stab at desublimationbetter, clearer, than most sourcespushing the word in a couple of ways: as loss and as strategy. On the one side, what one might call the conditional, desublimation points to those social conditions that foil the subjects capacity to sublimate libidinal demands and to differentiate experience within increasingly complex forms of social relations, knowledge, and production. And, on the other, which I would call the intentional, desublimation names the strategic foreground[ing of] the conflicting impulses within the aesthetic object itself. The social enforcement of sublimation is counteracted in anti-aesthetic gestures, processes or materials that discredit the sublimatory triumphalism made by the work of high art. As the glossarys discussion continues, it is clear that desublimation is played out, just where Kelley usually plays, in the dialectics of high art versus mass culture, performed throughout the twentieth century as a counter identication with the iconographies and the technologies of mass culture in order to debase the false autonomy claims with which modernism has propelled its myths.23 In this arrangement, cultural studies could be seen as both an effect of

Hal Foster, Rosalind Krauss, Y ve-Alain Bois, and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Art Since 1900: 22. Modernism, Anti-Modernism, Postmodernism (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2004), p. 30. Foster et al., Art Since 1900, pp. 68283. 23.

56

OCTOBER

desublimation, a product of the inability of even our smartest students and peers to differentiate high from lowtheir inability to not see things like everybody else sees them, as Kelley had itand an a priori surrender to it: a surrender to conditional desublimation of the tools of its critical or intentional uses. For its Adornian detractors, cultural studies gets to false autonomy far too easily and embraces heteronomy far too quickly, remorselessly (and uncritically) emptying out spaces for otherness or resistance. At certain points in the last century, one of those spaces was the unconscious, at least as it was imagined by Symbolism or Surrealism: irrational, irredeemably other, and thus not always already given up to the rationale of the culture industry or industrial culture, it could also stand as an analog for the autonomy of the work of art, and of the artist. Kelleys project, like that of the Surrealists, like that of his teacher Kamrowski, is to represent the unconscious, but his unconscious looks very different, and is located in a very different place. It is no longer the watery inscape of biomorphs and personages, radically other than the world; rather, it has been franchised. Introducing Kelleys future teacher to a Paris audience in 1950, Andr Breton wrote that of all the [American] newcomers, Kamrowski was the only one I found tunneling in a new direction.24 Breton links him to a familiar list of European modernsPicasso, De Chirico, Duchamp, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Ernst, Miras though forecasting a lineage that might include Kelley as well. But he concludes with a rupture that Kelley will only exaggerate: All that the Gerome Kamrowski. latter have bequeathed to Kamrowski is their pickaxe and The Student. 1950. lamp. Like Kamrowski, Kelley is a spelunker (indeed, he has been one since the 1985 Platos Cave, Rothkos Chapel, Lincolns Prole), and he too offers mists and miasma. The title of the 1998 work Sublevel: Dim Recollection Illuminated by Multicolored Swamp Gas seems a good enough description of Matta or Mir, or Kamrowski, but its conditions of representability, as Freud might have put it, are quite different. A three-dimensional memory map of the California Institute of the Arts sub-basement joined to the imaginary tunnels of the McMartin preschool, Sublevel is constructed in particle board and nished with red cast-resin panels intended to invoke the crystalline interiors of caves and geodes, and the softer, eshier interiors of the body. The conation of the cave and the female body is a Surrealist standard, of course, but Sublevel pushes its reference not toward Greek mythology or the Surrealist unknown but toward the annals of mass-cultural publication: Her darkness has been illuminated with a spotlight so all its glory is

24. Andr Breton, Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper and Row, 1972), p. 226.

Kelley. Sublevel detail (top) and installation view. 1998.

58

OCTOBER

revealed, Kelley writes in the accompanying catalog, as though of the insides of geodes, but he continues rather differently: In pornography, the split beaver shot is a fairly recent development. I do not think it existed before the 1970s.25 Perhaps, in the passage from one sentence to the next, we are supposed to hear what critic John Welchman described as the whiz of counter-repressive emergence, the adolescent guffaw for having lowered Surrealisms sights, and Freuds insights, to the level of Hustler magazine.26 But it seems to me, and to Herbert Marcuse writing in 1964 in the pages of One-Dimensional Man, the desublimatory tumble took place long before Kelley, at least the adult Kelley, ever got there. Something has fallen, a distinction has been lost, Marcuse complained, when you can nd Plato and Hegel, Shelley and Baudelaire, Freud and Marx in the drugstore.27 That imaginary spinner rack holds Marcuses reading list, too, of course, but his problem is not with the reading; it is with the drugstore, and those readers like Kelley who would take their Freud with or from Hustler. V. It is not only the drugstore that stands against Marcuse; what he termed repressive desublimation operates across a number of architectural sites. Among them, I would argue, are the institutions that Kelley has assembled as Educational Complex. Marcuse didnt name the college art department or the studio graduate-school modeled on the research university, as an aesthetic think tank;28 what he did say was this: Artistic alienation is sublimation.29 His argument here is a familiarly Frankfurtian one: alienation produces works of art that are irreconcilable with the established Reality Principle but which, as cultural images, become tolerable, even edifying and useful. Or at least alienation once did. Now this imagery is invalidated, not only by its appearance in the drugstore, but also by its incorporation into the kitchen, the ofce, the shop; its commercial release for business and fun is, in a sense, desublimation. Marcuses statement on the relationship between alienation and sublimation takes the form of an equation: not only is it reversible (sublimation is tantamount to artistic alienation, both cause and effect), but, as his corollary makes clear, the inverse is also true: dis-alienation, or for the time being let me say incorporation, is, in a sense, desublimation. And incorporation was the project of American art education across the rst half of the twentieth century, across the history that Educational Complex offers.

25. Mike Kelley, Sublevel: Dim Recollection Illuminated by Multicolored Swamp Gas, in Mike Kelley, Minor Histories, p. 105. 26. John Welchman, Survey: The Mike Kelleys, in Mike Kelley, 57. 27. Herbert Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man: Studies in the Ideology of Advanced Industrial Society (Boston: Beacon Press, 1964), p. 64. 28. The phrase was used early on by its founders to describe and differentiate CalArts. See Judith Adler, Artists in Ofces (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Books, 1979), p. 1. 29. Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, p. 72.

The Educational Complex

59

If we compose the buildings in Educational Complex not according to Hofmann, but in lived order, from Kelleys kindergarten and elementary days at St. Marys School in Wayne, to Adlai Stevenson Junior High and John Glenn High School, to the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and CalArts, we get something like a historical map of American art education, and the attempts across a century and a half to promulgate citizen-artists and art in everyday life. Michigans art program, like the studio departments in many public universities, began in a department of architecture in a school of engineering, as drawing and surface design for architects; art and design was carved out as a major in conjunction with the School of Education, with the addition of courses in watercolor and drawing for supervisors, art instructors, grade teachers, and school principals.30 At the turn of the last century, most American art students were in such teacher-training programs, bound with their displays and projects and banners for kindergarten or grade school classrooms, like those of St. Marys; or in architecture or design schools and bound, in ways that cut along class and gender lines, to ofces and high school drafting rooms. Art was taught to young men and women as a set of useful and marketable skills in relation to pliable and acceptable trades. For campus administrators and American commentators on art, the training of artistsat least of the kind of artist that a young Marcuse had written of in his 1922 Freiburg dissertation on the German Knstlerromantook place elsewhere, in Europe and in the past. The artists professional arrival on campus was still in the futureThe University of Michigan awarded its rst MFA in art in 1960 along with the promise of a different sort of artistic identity. Art at Michigan gained its full departmental autonomy more slowly than most; separate departments of art and architecture were created in the College of Architecture and Design in 1954, but a separate school of art and design wasnt formed until 1974, Kelleys last year on campus. The goals of those who championed teaching art in the university, rather than in ateliers and academies, had been not only to rationalize and streamline the teaching of artistsin no other profession, wrote the president of the nascent College Art Association in 1917, is there such a woeful waste of the raw material of human life as exists in certain phases of art education31but also, in doing so, to cure the artist of his physical and psychical isolation. Marcuse had written of this isolation, of a distinctly modern division between Knstlertum and Menschentum, early on; it was the very subject of his dissertation: the dissolution and tearing asunder of a unitary life-form, the opposition of art and life, the separation of the artist from the surrounding world, is the presupposition of the Knstlerroman, and its problem is the suffering and longing of the artist, his struggle for a new

30. Harlow O. Whittemore, The College of Art and Design, in The University of Michigan: An Encyclopedic Survey in Four Volumes, ed. Walter A. Donelly, vol. 3 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1953), p. 1307. 31. John Pickard, Presidents Address (April 6, 1917), Art Bulletin 1, no. 2 (1917), p. 43.

60

OCTOBER

community. 32 But the administrative pragmatism of commentators such as Carnegie Foundations R. L. Duffus, surveying American art education in the late 1920s, sits most uneasily with Marcuses critical historical understanding. In his brief for a professionalized university-based training, Duffus lampooned artistic struggle, and the training that has left the artist shut up in a little art universe all by himself, away from the swirl and ow of life, like a Trappist . . . offer[ing] up perfunctory prayers for the artistic salvation of a public which he despises. As though by at, or, perhaps, by curriculum design, the work of the artist ought to be just as necessary, just as understandable and in a way just as commonplace as that of the farmer, carpenter, and tailor. He ought to be friendly and human rst, then artistic.33 This might seem too unserious and too peculiarly journalistic to respond effectively to Marcuses ideal of artistic alienation, but there are weightier names than Duffuss who have pushed the social healthfulness and psychological cleanliness of art as a means of pushing it onto campuses. Making art a part of every students general education and insisting that those who would be artists be broadly and philosophically educated were intended, hand in hand, to give a rational healthy artist to a society able to embrace him. Any healthy man can become a musician, painter, sculptor, or architect, insisted Moholy-Nagy from the New Bauhaus; and any healthy man is precisely not the consumptive, be-garreted, neurotic genius of an older European model.34 By the 1960s, becoming an artist in the university could be, as Dan Flavin once put it in the pages of Artforum, a mature decision for intelligent individuals with a prerequisite of sound personally construed education35 perhaps an education like Kelleys, with its stepped courses in drawing and composition, two- and three-dimensional design, and a required class entitled Contemporary Art, Its Origins, which took as its subject the place of the artist and designer in contemporary society and the resulting art contributions.36 It is difcult to imagine what place Kelleys work might occupy within such a course, what it might contribute, or how it could sustain the glowingly professional image that Moholy-Nagy or Flavin offer. But it seems that art schools can desublimate, incorporate anything, producing for business and fun and tuition dollars even that work that would claim a more transgressive and critical desublimation. Art Center College of Design, where Kelley taught until 2006, recently offered a Transdisciplinary Studio entitled Loving Ugly: Art Drawn to the Offensive, Repugnant, and Dark Side of Life. This seems the very denition of

32. Herbert Marcuse, cited in Barry M. Katz, New Sources of Marcuses Aesthetics, review of Schriften I: Der deutsche Knstlerroman, Frhe Aufstze (1978), New German Critique 17 (Spring 1979), p. 177. 33. R. L. Duffus, The American Renaissance (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928), pp. 18687. 34. Lszl Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision (1928), 4th rev. ed., and Abstract of an Artist (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1947), p. 67. 35. Dan Flavin, On an American Artists Education, Artforum 6, no. 7 (March 1968), p. 31. 36. The University of Michigan Bulletin: School of Art 197475 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1974), p. 38.

The Educational Complex

61

repressive desublimation, produced by the commercial and ideological machinery of an afuent society from a position of strength on the part of society, which can afford to grant more than before because its interests have become the innermost drives of its citizens.37 While in the high art of the past, the refusal to behave may well have marked the critical appearance of the realm of freedom, it is not at all clear that such a course amounts to any sort of refusal; rather, in the classroom, it is precisely a kind of behaving.38 To return one last time to Marcuses equation, this desublimation is dis-alienation or, at the very least, dis-artistic alienation. The artist that such a course imagines is aggregated to a subculture (an identity, perhaps) afrmed and made whole as member or acionado. It is the promise of community, albeit not quite the community imagined by the artists of Marcuses Knstlerroman. Even for artists, the adjective artistic might not be an effective characterization of that site at which alienation is lived, if it is at all, nor of that place from which it is redeemed. In a certain light, one could argue that Kelley had begun to work with Marcuses desublimation long before Educational Complex, that his play goes back at least as far as his undergraduate paintings and the secondhand lessons of Hofmann. There is a kind of rhyme that Kelley played, that he intuited, perhaps, between Marcuses description of the conditions of desublimationthe attening out of critical historical categoriesand the German masters teaching on the organization of atness. The conquest and unication of opposites, which nds its ideological glory in the transformation of higher into popular culture, takes place on a material ground of increased satisfaction. This is also the ground which allows a sweeping desublimation.39 If the conquest and unication of opposites can be taken as something of a redescription of desublimation, it might also be taken as an oddly learned, or misrecognized, version of Hofmanns push-pull. Marcuses phrase rhymes nicely with a denition of push-pull that Irving Sandler offered in the catalog for the Whitney Museums 1990 Hofmann retrospective: it is an improvisational orchestration of areas of vivid colors conceived of as opposing forces, each force answered by a counter-force . . . so as to achieve an equilibrium and all-over intensity.40 By the time push-and-pull got to Kelley at Michigan, where, after all, Hofmann had come misspelled, color had dropped out of the equationthe question of what was to be put in tension had shifted in the face of Pop arts representations and the centered images and expansive elds of color eld painting. What Kelley learned to set in opposition, to use as force and counterforce atop a gestural ground, were not blocks of color but banks of images and bits of styles. His project, at least in retrospect, was to push and pull associations in a frame that had switched from the formal or visual to the cultural and ideological, where the tension was to be, could only be, between high and low, or inside

37. 38. 39. 40. Marcuse, One-Dimensional Man, p. 72. Ibid., p. 71. Ibid., pp. 7172. Irving Sandler, Hans Hofmann: The Dialectical Master, in Hans Hofmann, p. 79.

62

OCTOBER

and out, fringes and centers. I thought such surfaces could be used to great advantage in combination with various kinds of more loaded images, images that didnt lend themselves so easily to abstract equivalency.41 Kelleys student works are lled with awkward, attened juxtapositions, as are his revisited versions of them, but its not at all clear that he intended these images to hold together in the end, to achieve an equilibrium or all-over intensity, or a conquest and unity of opposites, or even how that was to be valued and in what register it might take place. I was always wondering, he told an interviewer, whether these collisions of style had any particular meaning, whether there was an ideological clash being represented, or whether the fact that it was paint just neutralized the conict.42 One way to read Kelleys comment is that, according to the intentional calculus of desublimation, painting as the very image of high art always wins, always sublimates in the end. But one could read it in reverse as well, that even then, in Kelleys school years, painting no longer provided a privileged ground on which to work; that it could no longer be debas[ed] with all means of deskilling or with abject or low-cultural iconography as it had been throughout modernity (my words here are borrowed once again from the same Art Since 1900 text). Kelleys problem with paint ing was that it would no longer t ake the fall. The hydraulics of the Freudian social subjectand the aesthetic dimension as its doublehad long since been attened out; or, more simply, the effects of deskilling and debasement had already been discounted, were already part of the teaching. In 1974, Kelleys painting was legible and gradable; it fulfilled his assignments, both explicit and implicit. VI. If painting could not do the work of negation, of protest[ing] against that which is, such was the explicit project of at least some of the images Kelley included in them. Those images would claim not only the negative work of irreconcilability, but offered an imagination of the new needs and new satisfactions that Marcuse linked to Eros and a real rather than repressive desublimation. Writing in 1967, he credited that imagination specically to communities of hippies and diggers, where sexual, moral, and political rebellion are somehow united; their aggressive nonaggressiveness offered, at least potentially, the demonstration of qualitatively different values, a transvaluation of values.43 I dont know that Kelley read Marcuse, though he easily could have picked up One-Dimensional Man or Eros and Civilization in any used bookstore in Ann Arbor.

Kelley, Missing Time, p. 65. 41. Mike Kelley, interviewed by Jean-Franois Chevrier, Galeries Magazine, no. 45 (OctoberNovember 42. 1991), p. 90. Herbert Marcuse, Liberation from the Affluent Society, in Critical Theory and Society: A 43. Reader, eds. Stephen Eric Bronner and Douglas McKay Kellner (New York: Routledge, 1989), p. 286.

The Educational Complex

63

Here let me offer a more immediate source for both the conjoining of sexual and political rebellion and for images as privileged site of ideological contestation: John Sinclairs White Panther Party, founded in Ann Arbor in November of 1968. Like the Black Panthers with whom they hoped to align, the White Panthers had a ten-point program, calling for a total assault on the culture by any means necessary, including rock n roll, dope and fucking in the streets, and in full aesthetico-utopian cry, Free time and space for all humansdissolve all unnatural boundaries. Those boundaries would include art school walls, or the precisely unnatural boundaries of the aesthetic dimension: We take our program with us everywhere we go. Our culture, our art, the music, newspapers, books, posters, our clothing, our homes, the way we walk and talk, the way our hair grows, the way we smoke dope and fuck and eat and sleepit is all one message, and the message is FREEDOM!44 This might be the real desublimation Marcuse envisioned, but, on the other hand, maybe not: after German university students occupied his ofces of the Institute for Social Research in early 1969, Adorno wrote to Marcuse, I nd it difcult to imagine that you had this type of desublimation in mind.45 According to Elisabeth Sussman, who curated Kelleys 1993 Whitney retrospective, Kelley was eetingly involved with the White Panthers at John Glenn High School, but by the time he left for the University of Michigan in the fall of 1972, he found the basic utopianism of the White Panthers an embarrassment. This does not imply, she argues, . . . that he could or wanted to give up the heroes of hip street culture and politics or to suppress the enormous appeal and interest this culture held for him. Rather, at Michigan, he was introduced to the rich variety of twentieth-century avant-garde experimentation in art and literature, and the creative potential of this legacy soon coexisted with his street lore and class attitudes.46 Sussmans language could scarcely be more determined; art, literature, avant-garde experimentation, and, perhaps most of all, legacy are clearly marshaled to trump hero-worship, lore, attitudes, and (on this side most of all) utopianism. The university marks the triumph of a tradition within which all of that other experience, other interest, is reduced precisely to interests, to subject matter for the project of art. Almost all the names Sussman drops from that point onand there are many, from Joseph Beuys and yvind Fahlstrm to LaMonte Young and Raymond Rousselare real artists, part of the legacy. Sussman (and, maybe, for that matter, Kelley) needs to prop up the tradition, to reassert a list of names that might just be all that is left of what Adorno or Marcuse thought of as the aesthetic dimension, in order for

44. John Sinclair, White Panther Party Statement, November 1, 1968, http://www.luminist.org/ archives/wpp.htm. 45. Theodor Adorno, letter to Herbert Marcuse, 19 June 1969, in Correspondence on the German Student Movement, introduced by Esther Leslie, New Left Review 1, no. 233 ( JanuaryFebruary 1999), p. 132. 46. Elisabeth Sussman, introduction to Mike Kelley: Catholic Tastes (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1993), pp. 1617.

64

OCTOBER

it to be deated again, in order to play out the ups and downs of abjection, of critical desublimation. Sinclairs White Panther appears only once in Kelleys work that I know of, in a piece entitled Entry Way (Genealogical Chart) that was exhibited alongside Educational Complex at Metro Pictures in 1995. Kelleys chart is a rerouted version of those signs at the entrances to towns and cities that announce civic organizat ions and welcome v isitor s and newcomer s; its an adult system, and, conventionally, a synchronic one. In Kelleys revision, however, in its title, its particular gridding, and in those pink and blue circles that recall genetic markers, the chart moves along the diachronic axis, from fathers to sons, from Elks, Lions, and Optimists, through the White Panther Party and the crossed rie and electric guitar of Sinclairs later Guitar Army, down to Ding-Dong School. Let me take Kelley at his word that this is a genealogical chart, and to pause at least briefly to note its distant family resemblance to Alfred Barrs famous genealogy of Cubism and abstract art. Kelleys Entry Way doesnt get us to or from Hofmann, rather, it charts a very different legacy, another set of influences. Kelley has wr itten t hat t he composit ion was determined by a genealogical chart of my immediate family,47 and one could easily imagine such a slide from the civic to the rebellious circa 1970, but Entry Way takes place most clearly, indeed absolutely, outside the immediacy of the family, as that family acts outor spins outwhat Marcuse, writing in the 1960s, termed the obsolescence of the Freudian concept of man.48 For Marcuse, it mattered that Freuds late-nineteenth-century subject was formed deep within the family, a crucible whose hierarchical structure left a fundamental dividing mark on the subject, setting in motion the multidimensional dynamic by which the individual attained and maintained his own balance between autonomy and heteronomy, freedom and repression, pleasure and pain. By the 1960s, whatever interiority might have belonged to the subject formed in the family seemed to Marcuse to have been fully unfolded in the social. The reality principle now spoke not through the father to the individual child in the family unit, but through the daily and nightly media which coordinate one privacy with that of all others, but also through the kids, the peer groups, the colleagues . . . the playmates, their neighbors, the leader of the gang, the sport, the screen: these are the authorities on appropriate mental and physical behavior. 49 These are new families, meanings, communities, desires. But to see the social fragmented and divided this way, and the subject in a sense undividedor at least no longer divided only in two, split along the axis of subjectivity, but rather unraveled, strung along a series of initiations and memberships, situated and interpellatedis to switch subjects, and maybe that

Kelley, Repressed Architectural Memory Replaced with Psychic Reality, p. 36. 47. Herbert Marcuse, The Obsolescence of the Freudian Concept of Man, in Critical Theory and 48. Society, p. 236. Ibid., p. 239. 49.

The Educational Complex

65

Kelley. Entry Way (Genealogical Chart). 1995.

is what Kelleys project has been about throughout . . . at least this is what I have been arguing throughout. His subject is not the deep subject of traditional psychoanalysis or for that matter of art history, but the atter subject of cultural studies. From its title on, Entry Way takes place inindeed it maps rather precisely what Rosalind Krauss has descr ibed as cultural studies domain: interpellationor in its more psychological guise, identicationis the very subject-eld of a whole new discipline that began to develop in the university . . . . This discipline, Cultural Studies, has set itself to systematize our understanding of the constitution of human subjects as so many identities that are not so much produced by their accession to a set of social conditions as they are reproduced through a process of (unconscious) identication with preexisting sources of authority and legitimation, whether these sources be people, institutions, or texts.50 Whether, to take the case at hand, they be Hofmann, the University of

50. Rosalind Krauss, Welcome to the Cultural Revolution, October 77 (Summer 1996), p. 85.

66

OCTOBER

Michigan, or the clarion call of the White Panthers, each of which comes with its texts, its authorities, and its modes of reproduction. Kelleys subject in Entry Way, and in the various hallways mapped in the bowels of Educational Complex, is the deposit of a social relationship, a phrase Foster borrows from Michael Baxandalls description of a fteenth-century painting in order to reattach it to the subject of cultural studies. Here, rather than the art, the subject is the deposit of social relations: indeed, he is ooded by the social. The shift from art history to visual culture is marked by a shift in principles of coherence, Foster continues, working his way to a word that Kelley, too, fell upon, from a history of style, or an analysis of form, to a genealogy of the subject.51 VII. Kelley may be using genealogy familiarly, to talk family; Foster, its clear, is using the term technically. His genealogy is Michel Foucaults: a way of writing history that can dispense with the constituent subject, that can account for the constitution of knowledges, discourses, domains of objects, etc., without having to make reference to a subject which is either transcendental in relation to the field of events or runs in empty sameness throughout the course of history.52 While this is no doubt comfortably old territory, the argument for a genealogical history should continue to pose a problem for art history. Certainly it troubles both the traditional subject of humanism, and its divided double, the subject of classical psychoanalysis. Beyond that, and here, for me, more importantly, what genealogy questions is the subject of history, or in our case, what the word art stands for in art history. Perhaps art needs to be derived, to be constructed in each moment in relat ion to it s inst itut ional and discur sive professional practices. Genealogically, autonomy comes to look like professional practice, which suggests, among other things, that genealogy insists on the present, while art historyat least that art history that makes art its continuous subjecttends to elide the present as it moves from the past to a future that its subject demands.53 This is, again, old news, perhaps, a theoretical position weve already discounted, but it does have specific ramifications for terms such as desublimation or deskilling, which in their shared prex de can only chart a fall from grace, precisely as it instantiates and constitutes its subject; desublimation demands of its readers that we make sublimation the characteristic and, indeed, permanent mechanism of something called art, that has always already been art. The footnotes here are not only to Foucault but to Jean Baudrillard or even Allan Kaprow: desublimation secures art, it inoculates it against its disappearance in the present. Clearly, cultural studies poses a threat, or did in the pages of October in

51. 52. 53. Hal Foster, The Archive without Museums, October 77 (Summer 1996), p. 103. Michel Foucault, cited in ibid. See Lane Relyea, Art by Degrees, Frieze 49 (NovemberDecember 1999), pp. 5456.

The Educational Complex

67

1996now a long time ago, but not too long after Kelleys Educational Complex was installed at Metro Pictures. The production of the discourse of visual culture entails the liquidation of art as we know it. There is no way within such a discourse for art to sustain a separate existence, not as a practice, not as a phenomenon, not as an experience, not as a discipline.54 Its hard to know now how exactly Susan Buck-Morss intended those words to be read, in what tone of voice: in anger, in sadness, maybe in triumph. Like a number of contributors to Octobers special number on visual culture, she situated visual cultures practices and effects not abroad in some new and proliferating image world, but fully and insistently in the university, and in its internal forms and politics. What proliferates, it seems, are programs and students: The producers of the visual culture of tomorrow are the camera-women, film/video editors, city planners, set designers for rock stars, tourism packagers, marketing consultants, political consultants, television producers, commodity designers, layout persons, and cosmetic surgeons . . . . They are the students who sit in our classes today. What is it they need to know? What will be gained, and by whom, in offering them a program in visual studies?55 Buck-Morsss list of professions and semi-professions is astonishing, but it is also distressingly familiar; it recites the burgeoning lists of certicate and degree programs of any number of colleges and universities now fully excellent, or fully in ruins, to borrow terms from the late Bill Readings.56 Here, or rather, now, students are no longer formed or gebildet, but allowed to realize themselves according to their interests and memberships into slots already made. It is alsolike most complaints against the onslaught of cultural studies, or of one-dimensional mana seemingly endless list. Mike Kelleys work mimics the terms and descriptions of cultural studies, specically as it is described by its harshest critics and caricaturists, by those who see it as political surrender or intellectual weaknessas one more piece of the same decline and fall. But when I write, particularly in these pages, that Kelleys subject is the subject of cultural studies, what I want to suggest is not his criticality, nor, one more time, his desublimating urge, nor his acquiescence to something some might still see as the terrors of mass culture. Rather, what I want to end up saying is that I take him as its teacher, a professor of cultural studies, in the university with the rest of uswhich is, after all, where his research and his work have been thematically for the past decade. Kelleys project has long been a study of the visual culture of high school and college, and the university art department, but it might also be helpful to understand the stakes for us. Against an art history of the museum, or one that takes the museum and the past that it stands for as the seat of its power, cultural studies base is the university, and maybe particularly the classroom that Buck-Morss, like Kelley, evokes so powerfully. It dwells, complained Krauss (and again it is difficult to

54. 55. 56. Susan Buck-Morss, response to Visual Culture Questionnaire, October 77 (Summer 1996), p. 29. Ibid., pp. 3031. Bill Readings, The University in Ruins (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996).

68

OCTOBER

catch exactly the tone of voice, or the site from where exactly this is seen), in that part of the Academy that likes to think of itself as avant-garde.57 But the value of Kelleys work, and of a Foucauldian cultural studies, might be just that focus on our institutions and discourses, on how artists or, for that matter, art historians are formedor interpellatedand where they, too, perform and police their disciplines. If all the history of art can do here, in relation to the present most of us nd ourselves in, is to record again our losses and lacks, or, in nearly the same breath, our acts of brave criticism against a stand-up autonomy, perhaps what we need cultural studies for is to remind us of our institutional entanglements, our memberships and investments.

57.

Krauss, Welcome to the Cultural Revolution, p. 92.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Utopian Globalists: Artists of Worldwide Revolution, 1919 - 2009Von EverandThe Utopian Globalists: Artists of Worldwide Revolution, 1919 - 2009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hal Foster Which Red Is The Real Red - LRB 2 December 2021Dokument12 SeitenHal Foster Which Red Is The Real Red - LRB 2 December 2021Leonardo NonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buchloh Figures of Authority PDFDokument31 SeitenBuchloh Figures of Authority PDFIsabel BaezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francis Alys Exhibition PosterDokument2 SeitenFrancis Alys Exhibition PosterThe Renaissance SocietyNoch keine Bewertungen

- October's PostmodernismDokument12 SeitenOctober's PostmodernismDàidalos100% (1)

- CONCEPTUAL+ART Handout+3 8 17Dokument3 SeitenCONCEPTUAL+ART Handout+3 8 17Richel BulacosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Decorative, Abstraction, and The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in The Art Criticism of GreenbergDokument25 SeitenThe Decorative, Abstraction, and The Hierarchy of Art and Craft in The Art Criticism of GreenbergSebastián LomelíNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buntix, Gustavo y Ivan Kamp - Tactical MuseologiesDokument7 SeitenBuntix, Gustavo y Ivan Kamp - Tactical MuseologiesIgnacia BiskupovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- After The White CubeDokument6 SeitenAfter The White CubeGiovanna Graziosi CasimiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brian Holmes - Recapturing Subversion - Twenty Twisted Rules of The Culture GameDokument15 SeitenBrian Holmes - Recapturing Subversion - Twenty Twisted Rules of The Culture GameAldene RochaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blake Gopnik On Hiroshi SugimotoDokument4 SeitenBlake Gopnik On Hiroshi SugimotoBlake GopnikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baird - The Abject, The Uncanny, and The SublimeDokument14 SeitenBaird - The Abject, The Uncanny, and The SublimejinnkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Red Art New Utopias in Data CapitalismDokument250 SeitenRed Art New Utopias in Data CapitalismAdam C. PassarellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bois Krauss Intros3 4 ArtSince1900Dokument17 SeitenBois Krauss Intros3 4 ArtSince1900Elkcip PickleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtDokument27 SeitenFoster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtEdsonCosta87Noch keine Bewertungen

- Alain Bowness - Symbolism (Chapter 4)Dokument8 SeitenAlain Bowness - Symbolism (Chapter 4)KraftfeldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Figures of Authority, Ciphers of RegressionDokument31 SeitenFigures of Authority, Ciphers of RegressioncuyanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gregory Battcock - Minimal ArtDokument7 SeitenGregory Battcock - Minimal ArtLarissa CostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sternberg Press - July 2017Dokument11 SeitenSternberg Press - July 2017ArtdataNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pictorial Jeff WallDokument12 SeitenThe Pictorial Jeff WallinsulsusNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01-Gutai ArtDokument28 Seiten01-Gutai ArtДщъы АнопрстфхцNoch keine Bewertungen

- Italian Futurism and RussiaDokument7 SeitenItalian Futurism and RussiaMadhumoni DasguptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Terry Smith: Questionnaire On "The Contemporary" OCTOBER 130, Fall 2009Dokument9 SeitenTerry Smith: Questionnaire On "The Contemporary" OCTOBER 130, Fall 2009MERODENENoch keine Bewertungen

- Ernst Gombrich - The Break in Tradition (Ch. 24)Dokument23 SeitenErnst Gombrich - The Break in Tradition (Ch. 24)Kraftfeld100% (1)

- Bourriaud PostproductionDokument47 SeitenBourriaud Postproductionescurridizo20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mike Kelley - Shall We Kill DaddyDokument12 SeitenMike Kelley - Shall We Kill DaddyCineclubdelItae100% (1)

- Balla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseDokument3 SeitenBalla and Depero The Futurist Reconstruction of The UniverseRoberto ScafidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Joselit, Notes On Surface-Toward A Genealogy of FlatnessDokument16 SeitenDavid Joselit, Notes On Surface-Toward A Genealogy of FlatnessAnonymous wWRphADWzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hal Foster - The Archives of Modern ArtDokument15 SeitenHal Foster - The Archives of Modern ArtFernanda AlbertoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pop Art A Reactionary Realism, Donald B. KuspitDokument9 SeitenPop Art A Reactionary Realism, Donald B. Kuspithaydar.tascilarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Primitivism and The OtherDokument13 SeitenPrimitivism and The Otherpaulx93xNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Uncanny, Mike KelleyDokument5 SeitenThe Uncanny, Mike KelleyLuis Miguel ZeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daston & Galison - The Image of ObjectivityDokument49 SeitenDaston & Galison - The Image of ObjectivityGabriela LunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Falling Into The Digital Divide: Encounters With The Work of Hito Steyerl by Daniel RourkeDokument5 SeitenFalling Into The Digital Divide: Encounters With The Work of Hito Steyerl by Daniel RourkeDaniel RourkeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarDokument21 SeitenLeighten Picassos Collages and The Threat of WarmmouvementNoch keine Bewertungen

- Passaic Boys Are Hell: Robert Smithson's Tag As Temporal and Spatial Marker of The Geographical SelfDokument14 SeitenPassaic Boys Are Hell: Robert Smithson's Tag As Temporal and Spatial Marker of The Geographical SelfazurekittyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rosalyn Deutsche, Uneven DevelopmentDokument51 SeitenRosalyn Deutsche, Uneven DevelopmentLauren van Haaften-SchickNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 - An Essay by Carolyn Christov-BakargievDokument16 Seiten4 - An Essay by Carolyn Christov-BakargievSilva KalcicNoch keine Bewertungen

- +boris Groys - The Curator As Iconoclast.Dokument7 Seiten+boris Groys - The Curator As Iconoclast.Stol SponetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kounellis - PradaDokument3 SeitenKounellis - PradaArtdataNoch keine Bewertungen

- !.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1Dokument4 Seiten!.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1tendermangomangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrian Rifkin, Marx's ClarkismDokument9 SeitenAdrian Rifkin, Marx's ClarkismDaniel SpauldingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art and Archive 1920-2010Dokument18 SeitenArt and Archive 1920-2010Mosor VladNoch keine Bewertungen

- George Baker Ed 2003 James Coleman October Books MIT Essays by Raymond Bellour Benjamin H D Buchloh Lynne Cooke Jean Fisher Luke Gib PDFDokument226 SeitenGeorge Baker Ed 2003 James Coleman October Books MIT Essays by Raymond Bellour Benjamin H D Buchloh Lynne Cooke Jean Fisher Luke Gib PDFAndreea-Giorgiana MarcuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Georges Didi-Huberman - Picture Rupture. Visual Experience, Form and Symptom According To Carl EinsteinDokument25 SeitenGeorges Didi-Huberman - Picture Rupture. Visual Experience, Form and Symptom According To Carl Einsteinkast7478Noch keine Bewertungen

- Kester, Lesson in FutilityDokument15 SeitenKester, Lesson in FutilitySam SteinbergNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Post-Contemporary Interventions) D. N. Rodowick-Reading The Figural, Or, Philosophy After The New Media - Duke University Press Books (2001)Dokument297 Seiten(Post-Contemporary Interventions) D. N. Rodowick-Reading The Figural, Or, Philosophy After The New Media - Duke University Press Books (2001)Tarik AylanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coco Fusco On Chris OfiliDokument7 SeitenCoco Fusco On Chris OfiliAutumn Veggiemonster WallaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Hammons Follows His Own RulesDokument19 SeitenDavid Hammons Follows His Own RulesMaria BonomeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claire Bishop Black - Box - White - Cube - Gray - Zone - Dance - Exh PDFDokument22 SeitenClaire Bishop Black - Box - White - Cube - Gray - Zone - Dance - Exh PDFCorpo EditorialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Situationist ManifestoDokument3 SeitenSituationist ManifestoRobert E. HowardNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Dokument16 SeitenNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catálogo - Torres-GarcíaDokument31 SeitenCatálogo - Torres-GarcíaB.L.ANoch keine Bewertungen

- OckmanDokument41 SeitenOckmanatarmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physicality of Picturing... Richard ShiffDokument18 SeitenPhysicality of Picturing... Richard Shiffro77manaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curating Architecture - Irina Verona - Columbia UniversityDokument7 SeitenCurating Architecture - Irina Verona - Columbia UniversityFelipe Do AmaralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claire Bishop IntroductionDokument2 SeitenClaire Bishop IntroductionAlessandroValerioZamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Godfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDokument35 SeitenGodfrey, Mark - The Artist As HistorianDaniel Tercer MundoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Susan Sontag-Against Interpretation PDFDokument5 SeitenSusan Sontag-Against Interpretation PDFHasanhan Taylan Erkıpçak100% (6)

- Alloway-Network Art and A ComplexPresentDokument9 SeitenAlloway-Network Art and A ComplexPresenttemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Time Again PressDokument17 SeitenTime Again Presstemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art Since 1900Dokument36 SeitenArt Since 1900temporarysite_org100% (2)

- Dexter DalwoodDokument3 SeitenDexter Dalwoodtemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exegesis:When We Build Let Us Think That We Build ForeverDokument6 SeitenExegesis:When We Build Let Us Think That We Build Forevertemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issue Nr. 77 / March 2010 "Painting"Dokument4 SeitenIssue Nr. 77 / March 2010 "Painting"temporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Third Text WrightDokument13 SeitenThird Text Wrighttemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artistic Autonomy Etc Brian HolmesDokument9 SeitenArtistic Autonomy Etc Brian Holmestemporarysite_org100% (1)

- New Institutional IsmDokument12 SeitenNew Institutional Ismtemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. VistavisionDokument24 SeitenPierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. Vistavisiontemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artistic Education - RifkinDokument4 SeitenArtistic Education - Rifkintemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- ContingencyDokument9 SeitenContingencyNicolás LamasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Feathers of The Eagle: Sven LüttickenDokument17 SeitenThe Feathers of The Eagle: Sven Lüttickentemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire On The Contemporary. OCTOBER 130, Fall 2009, pp.3-124.Dokument122 SeitenQuestionnaire On The Contemporary. OCTOBER 130, Fall 2009, pp.3-124.Theresa Plunkett-HillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Here There and - RaunigDokument3 SeitenHere There and - Raunigtemporarysite_orgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complications On Collaboration, Agency and Contemporary ArtDokument22 SeitenComplications On Collaboration, Agency and Contemporary Arttemporarysite_org100% (1)

- NVIDIA Professional Graphics SolutionsDokument2 SeitenNVIDIA Professional Graphics SolutionsJohanes StefanopaulosNoch keine Bewertungen

- FXO Gateway Setting For ElastixDokument7 SeitenFXO Gateway Setting For ElastixAlejandro LizcanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TAC General 0091192 Tac Vista Catalogue Scheneider 2008Dokument108 SeitenTAC General 0091192 Tac Vista Catalogue Scheneider 2008Pello InsaustiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 - The Basics of Server and Web Server AdministrationDokument8 SeitenChapter 1 - The Basics of Server and Web Server Administrationghar_dashNoch keine Bewertungen

- BILLING NO.2 - Daanlungsod-Calangahan DetailedDokument1 SeiteBILLING NO.2 - Daanlungsod-Calangahan Detailedanthony christian yangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Network Time ProtocolDokument19 SeitenNetwork Time Protocoljayanth_babluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover LetterDokument2 SeitenCover LetterFifi Rahima YantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0 - E2461-12 Standard Practice For Determining The Thickness of Glass in Airport Traffic Control Tow PDFDokument17 Seiten0 - E2461-12 Standard Practice For Determining The Thickness of Glass in Airport Traffic Control Tow PDFMina AdlyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dungeon Magazine Chaos Scar CampaignDokument396 SeitenDungeon Magazine Chaos Scar CampaignJ100% (10)

- Concrete Rate Analysis: Grade of Concrete (N/MM )Dokument2 SeitenConcrete Rate Analysis: Grade of Concrete (N/MM )Debarshi SahooNoch keine Bewertungen

- VoQuangHai CVDokument6 SeitenVoQuangHai CVvietechnoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SRIM ReadMe (English-2011)Dokument4 SeitenSRIM ReadMe (English-2011)Miguel MagallanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stratford 2004Dokument10 SeitenStratford 2004carlrequiolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sand ColumnDokument16 SeitenSand ColumnZulfadli MunfazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chiller YorkDokument76 SeitenChiller YorkJosaphat Avila RodriguezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Migrating To H3C Lab Guide Lab01 Basic Config v2.8Dokument32 SeitenMigrating To H3C Lab Guide Lab01 Basic Config v2.8Vargas AlvaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leveraging COBIT To Implement Information SecurityDokument29 SeitenLeveraging COBIT To Implement Information SecurityZaldy GunawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Etsi Eg 202 057-1Dokument34 SeitenEtsi Eg 202 057-1Dusan JokanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suprematism Manifesto Unovis PDFDokument2 SeitenSuprematism Manifesto Unovis PDFclownmunidade100% (2)

- Think WoodDokument10 SeitenThink WoodkusumoajiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Architecture - Sustainable Urban DesignDokument28 SeitenArchitecture - Sustainable Urban Designlucaf79100% (2)

- Rural Bank: Case StudyDokument10 SeitenRural Bank: Case StudyChelsea DyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nexans Cabling Best Practices v6.2Dokument33 SeitenNexans Cabling Best Practices v6.2Oageng Escobar Baruti100% (1)

- Marley Aquatower - User ManualDokument28 SeitenMarley Aquatower - User ManualVILLANUEVA_DANIEL2064Noch keine Bewertungen

- Geetest InstallationDokument4 SeitenGeetest InstallationNarutõ UzumakiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- F25 - FGB Metro Station To Al Qouz LNDL Area 3&4 Dubai Bus Service TimetableDokument8 SeitenF25 - FGB Metro Station To Al Qouz LNDL Area 3&4 Dubai Bus Service TimetableDubai Q&ANoch keine Bewertungen

- Contoh Company ProfileDokument10 SeitenContoh Company ProfilePoedya Samapta Catur PamungkasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Node JsDokument32 SeitenNode Jssteamer92Noch keine Bewertungen

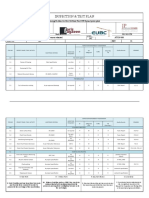

- Inspection & Test PlanDokument2 SeitenInspection & Test PlanKhaled GamalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lal-Dora - in The High Court of Delhi at New DelhiDokument30 SeitenLal-Dora - in The High Court of Delhi at New DelhiEva SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen