Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

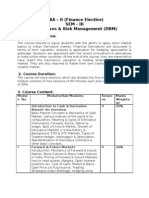

Project - Portfolio Mgmt. & Investment Analysis-Working-08.02.11

Hochgeladen von

kittysingla40988Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Project - Portfolio Mgmt. & Investment Analysis-Working-08.02.11

Hochgeladen von

kittysingla40988Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Introduction

We all dream of beating the market and being super investors and spend an inordinate amount of time and resources in this endeavor. Consequently, we are easy prey for the magic bullets and the secret formulae offered by eager salespeople pushing their wares. In spite of our best efforts, most of us fail in our attempts to be more than average investors. Nonetheless, we keep trying, hoping that we can be more like the investing legends another Warren Buffett or Peter Lynch. We read the words written by and about successful investors, hoping to find in them the key to their stock-picking abilities, so that we can replicate them and become wealthy quickly. In our search, though, we are whipsawed by contradictions and anomalies. In one corner of the investment townsquare, stands one advisor, yelling to us to buy businesses with solid cash flows and liquid assets because that what worked for Buffett. In another corner, another investment expert cautions us that this approach worked only in the old world, and that in the new world of technology, we have to bet on companies with solid growth prospects. In yet another corner, stands a silver tongued salesperson with vivid charts and presents you with evidence of his capacity to get you in and out of markets at exactly the right times. It is not surprising that facing this cacophony of claims and counterclaims that we end up more confused than ever. In this introduction, we present the argument that to be successful with any investment strategy, you have to begin with an investment philosophy that is consistent at its core and which matches not only the markets you choose to invest in but your individual characteristics. In other words, the key to success in investing may lie not in knowing what makes Peter Lynch successful but in finding out more about yourself

Most investors leave the more technical aspects of portfolio management to their financial consultants. However, this need not be the case. The average educated person can certainly gain a grasp of the topic sufficient enough to make his or her own investment decisions. The key to learning is gaining the knowledge and then practice applying it to your own portfolio in small amounts until you feel confident enough to manage it completely on your own. This article will briefly describe some of the concepts behind portfolio theory as well as some general techniques applied by portfolio managers. There are many good books 1

that can give more in depth information if you feel this is something you would like to know more about. The first important fact of portfolio management is understanding the two main decisions, which are related but completely separate for purposes of practicality. These two decisions are 1) Broad-based asset allocation and 2) Specific security selection The most important thing an investor can do is go through the in-depth process of determining a portfolio asset mix at the very onset of each year and again anytime there is a significant change to their portfolio. It is only after this mix is determined that the process of choosing individual investments should be made. Asset classes are by far a bigger factor in overall performance than individual security selection as time invested increases. Or to put this in a more pragmatic way, it doesnt matter in a 10-year period of time which stock you chose as much as it matters that you chose stock. This doesnt mean an individual security cant make a difference. It just means that it becomes less important over a period of five years or so since all securities of a given class tend to move toward an average performance which balances out extreme movements in specific periods of time. Another important fact of portfolio management is that one makes analytical decisions and not make decisions based on hunches or emotion. This kind of pragmatic and analytical approach will keep the average investor from making decisions to move money completely in or out of a security or an asset class based upon the latest market rumors or the five oclock news. Regardless of what insight we feel inclined to follow, the numbers and the data of past performance gives us clear indications that moving in and out of asset classes or individual securities during adverse periods hurts more than it helps in the long run. And if a decision is made to divest out of a specific security, it is always advised to dollar-cost average out of the investment in the same manner that one should have dollar-cost averaged in. Dollar cost averaging is a technique by which an investor divides the given investment over a period of time and invests that amount on a regular basis as opposed to buying in all at once. This technique is covered in more detail in a previous article.

Objectives of Portfolio Management:The objective of portfolio management is to invest in securities is securities in such a way that one maximizes ones returns and minimizes risks in order to achieve ones investment objective. A good portfolio should have multiple objectives and achieve a sound balance among them. Any one objective should not be given undue importance at the cost of others. Presented below are some important objectives of portfolio management. 1. Stable Current Return: Once investment safety is guaranteed, the portfolio should yield a steady current income. The current returns should at least match the opportunity cost of the funds of the investor. What we are referring to here current income by way of interest of dividends, not capital gains. 2. Marketability: A good portfolio consists of investment, which can be marketed without difficulty. If there are too many unlisted or inactive shares in your portfolio, you will face problems in encasing them, and switching from one investment to another. It is desirable to invest in companies listed on major stock exchanges, which are actively traded. 3. Tax Planning: Since taxation is an important variable in total planning, a good portfolio should enable its owner to enjoy a favorable tax shelter. The portfolio should be developed considering not only income tax, but capital gains tax, and gift tax, as well. What a good portfolio aims at is tax planning, not tax evasion or tax avoidance. 4. Appreciation in the value of capital: A good portfolio should appreciate in value in order to protect the investor from any erosion in purchasing power due to inflation. In other words, a balanced portfolio must consist of certain investments, which tend to appreciate in real value after adjusting for inflation. 5. Liquidity:

The portfolio should ensure that there are enough funds available at short notice to take care of the investors liquidity requirements. It is desirable to keep a line of credit from a bank for use in case it becomes necessary to participate in right issues, or for any other personal needs. 6. Safety of the investment: The first important objective of a portfolio, no matter who owns it, is to ensure that the investment is absolutely safe. Other considerations like income, growth, etc., only come into the picture after the safety of your investment is ensured. Investment safety or minimization of risks is one of the important objectives of portfolio management. There are many types of risks, which are associated with investment in equity stocks, including super stocks. Bear in mind that there is no such thing as a zero risk investment. More over, relatively low risk investment give correspondingly lower returns. You can try and minimize the overall risk or bring it to an acceptable level by developing a balanced and efficient portfolio. A good portfolio of growth stocks satisfies the entire objectives outline above. Scope of Portfolio Management:Portfolio management is a continuous process. It is a dynamic activity. The following are the basic operations of a portfolio management. a) Monitoring the performance of portfolio by incorporating the latest market conditions. b) Identification preferences. of the investors objective, constraints and

c) Making an evaluation of portfolio income (comparison with targets and achievement). d) e) Making revision in the portfolio. Implementation of the strategies in tune with investment objectives

Portfolio Management is used to select a portfolio of new product development projects to achieve the following goals:

Maximize the profitability or value of the portfolio Provide balance Support the strategy of the enterprise Portfolio Management is the responsibility of the senior management team of an organization or business unit. This team, which might be called the Product Committee, meets regularly to manage the product pipeline and make decisions about the product portfolio. Often, this is the same group that conducts the stage-gate reviews in the organization.

Theoretical Perspective

The art and science of making decisions about investment mix and policy, matching investments to objectives, asset allocation for individuals and institutions, and balancing risk against performance. Portfolio management is all about SWOT analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) in the choice of debt vs. equity, domestic vs. international, growth vs. safety, and many other tradeoffs encountered in the attempt to maximize return at a given appetite for risk.

In the case of mutual and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), there are two forms of portfolio management: passive and active. Passive management simply tracks a market index, commonly referred to as indexing or index investing. Active management involves a single manager, co-managers, or a team of managers who attempt to beat the market return by actively managing a fund's portfolio through investment decisions based on research and decisions on individual holdings. Closed-end funds are generally actively managed. Portfolio Management is used to select a portfolio of new product development projects to achieve the following goals: Maximize the profitability or value of the portfolio 5

Provide balance Support the strategy of the enterprise Portfolio Management is the responsibility of the senior management team of an organization or business unit. This team, which might be called the Product Committee, meets regularly to manage the product pipeline and make decisions about the product portfolio. Often, this is the same group that conducts the stage-gate reviews in the organization. A logical starting point is to create a product strategy - markets, customers, products, strategy approach, competitive emphasis, etc. The second step is to understand the budget or resources available to balance the portfolio against. Third, each project must be assessed for profitability (rewards), investment requirements (resources), risks, and other appropriate factors. The weighting of the goals in making decisions about products varies from company. But organizations must balance these goals: risk vs. profitability, new products vs. improvements, strategy fit vs. reward, market vs. product line, long-term vs. short-term. Several types of techniques have been used to support the portfolio management process: Heuristic models Scoring techniques Visual or mapping techniques The earliest Portfolio Management techniques optimized projects' profitability or financial returns using heuristic or mathematical models. However, this approach paid little attention to balance or aligning the portfolio to the organization's strategy. Scoring techniques weight and score criteria to take into account investment requirements, profitability, risk and strategic alignment. The shortcoming with this approach can be an over emphasis on financial measures and an inability to optimize the mix of projects. Mapping techniques use graphical presentation to visualize a portfolio's balance. These are typically presented in the form of a two-dimensional graph that shows the tradeoff's or balance between two factors such as risks vs. profitability, marketplace fit vs. product line coverage, financial return vs. probability of success, etc. Our recommended approach is to start with the overall business plan that should define the planned level of R&:D investment, resources (e.g., headcount, etc.), and related sales expected from new products. With 6

multiple business units, product lines or types of development, we recommend a strategic allocation process based on the business plan. This strategic allocation should apportion the planned R&D investment into business units, product lines, markets, geographic areas, etc. It may also breakdown the R&D investment into types of development, e.g., technology development, platform development, new products, and upgrades/enhancements/line extensions, etc. Once this is done, then a portfolio listing can be developed including the relevant portfolio data. We favor use of the development productivity index (DPI) or scores from the scoring method. The development productivity index is calculated as follows: (Net Present Value x Probability of Success) / Development Cost Remaining. It factors the NPV by the probability of both technical and commercial success. By dividing this result by the development cost remaining, it places more weight on projects nearer completion and with lower uncommitted costs. The scoring method uses a set of criteria (potentially different for each stage of the project) as a basis for scoring or evaluating each project. An example of this scoring method is shown with the worksheet below. Weighting factors can be set for each criteria. The evaluators on a Product Committee score projects (1 to 10, where 10 is best). The worksheet computes the average scores and applies the weighting factors to compute the overall score. The maximum weighted score for a project is 100. Once the organization has its prioritized list of projects, it then needs to determine where the cutoff is based on the business plan and the planned level of investment of the resources available. This subset of the high priority projects then needs to be further analyzed and checked. The first step is to check that the prioritized list reflects the planned breakdown of projects based on the strategic allocation of the business plan. Pie charts such as the one below can be used for this purpose. Other factors can also be checked using bubble charts. For example, the risk-reward balance is commonly checked using the bubble chart shown earlier. A final check is to analyze product and technology roadmaps for project relationships. For example, if a lower priority platform project was omitted from the portfolio priority list, the subsequent higher priority projects that depend on that platform or platform technology would be impossible to execute unless that platform project were included in the portfolio priority list. An example of a roadmap is shown below.

Finally, this balanced portfolio that has been developed is checked against the business plan as shown below to see if the plan goals have been achieved - projects within the planned R&D investment and resource levels and sales that have met the goals. With the significant investments required to develop new products and the risks involved, Portfolio Management is becoming an increasingly important tool to make strategic decisions about product development and the investment of company resources. In many companies, current year revenues are increasingly based on new products developed in the last one to three years. Therefore, these portfolio decisions are the basis of a company's profitability and even its continued existence over the next several years. INVESTMENT ANALYSIS Investment analysis is an ongoing process of evaluating current and potential allocations of financial assets and choosing those allocations that best fit the investor's needs and goals. The two opposing considerations in investment analysis are growth rate and risk, which are usually directly proportionate in any given investment vehicle. This means that investments with a high degree of certainty, such as securities, offer a very modest rate of return, whereas high-risk stock investments could double or quadruple in value over a few months. Through investment analysis, investors must consider the level of risk they're able to tolerate and choose investments accordingly. Beyond weighing the return of an individual investment, investors must also consider taxes, transaction costs, and opportunity costs that erode their net return. Taxes, for instance, may be reduced or deferred depending on the type of investment and the investor's tax status. Transaction costs may be incurred each time an individual purchases or sells shares of stock or mutual funds. These fees are usually a percentage of the dollar amount being transferred. Such fees may sift 36 percent or more off the initial investment and final return. If they don't seem warranted, such expenses may be avoided by choosing no load mutual funds and dealing with discount brokers, for instance. Much more nebulous is opportunity cost, which is what the investment could have earned had it been deployed elsewhere. Opportunity cost is largely the downside of investing too conservatively given one's means and circumstances. Again, both risk and growth factor into opportunity costs. For example, low risk comes at a price of low returns, but it may be worth the lost opportunity if the investor is retired and will be depending on the invested funds for living expenses in the near future. INTEREST-BEARING INVESTMENTS AND TREASURIES 8

Among the lowest riskand lowest returninvestments are interestbearing notes such as money market funds, certificates of deposit from banks notes and bonds. These pay the investor a guaranteed periodic interest payment, or, in the case of T-bills, a lump sum based on a guaranteed discount rate. To choose between the various options the investor need only consider the comparative interest rate (some pay more than others) and the term (many of these investments are based on fixed periods such as three months or a year). These sorts of investments are popular because they are fairly liquidthey can be bought and sold at any point in a financial cycle without adverse timing effectsand they offer a nearly risk-free option for investors who need certainty of return. MUTUAL FUNDS Mutual funds lure investors with the promise of stock market-like returns in a lower risk and more novice-friendly environment. These funds pool their members' investments in professionally managed portfolios of stocks, bonds, and other investments. As a result, they can provide individual investors with the kind of investment diversification that would otherwise require a much greater amount of money to be invested and much more effort in reviewing the many choices. In the 1980s and 1990s mutual funds were increasingly used for employeemanaged retirement savings programs. Most funds have an investment objective and, as with stocks, the choices range from conservative, low risk funds that mirror a market index like the Standard & Poor's 500 to high-stakes aggressive growth funds that focus on small and unproven companies. Also like stocks, many funds perform poorly in a given year or even over a period of years, a fact that fund marketers sometimes gloss over. Thus choosing mutual funds involves many of the same considerations as choosing stocks. FUTURES AND OTHER DERIVATIVES While investments like oil futures and options are often seen as some of the riskiest forms of investment, ironically a key use for these markettraded contracts is for hedging against adverse movements in cash markets. In other words, investors buy futures or options contracts in part to reduce their risk of facing a devastating price fall (or increase, as the case may be) in another market. Collectively, futures, options, and similar instruments are known as derivatives because they derive from price movements in other markets, including commodities, currencies, and stocks. Of course, many investors also use derivatives for speculation. By nature the individual contracts are short-term investments, although some investors, mainly corporations and other 9

institutions, maintain a regular portfolio of derivatives on underlying commodities or assets that affect their business. Analyzing futures and options involves analyzing the expected direction of price movements for the underlying goods. However, in contrast to stock or mutual fund analysis, which is usually best done with an eye to the long term, derivative analysis requires making a short-term (less than a year) forecast of what might happen to prices in the cash markets. If the forecast proves accurate the investor can make money, but if it's wrong the losses could be substantial. With the practice of buying on margin, which involves taking out a loan to increase the amount of the investment, the profits or losses can be multiplied. SECURITIES A security is a financial asset representing a claim on the assets of the issuing firm and on the profits produced by the assets. The term security analysis pertains to the process of identifying desirable investment opportunities in such financial assets. In the case of corporate stocks and bonds, the analysis flows from the interpretation of accounting and financial data regarding operations, profitability, net worth, and the like. Investment alternatives are identified based on (1) the investor's risk/reward ratio, (2) a specified time horizon, and (3) current market prices. Security analysts, in essence, are the catalysts which drive the efficient market hypothesis. That is, "smart" money will logically and efficiently distribute itself in such a way that security prices reflect all available information. As new information becomes available, analysts assess it and recommend market price adjustments according to changes they anticipate for price levels. The cumulative impact of price adjustments moves the market to equilibrium so that the price of any security approximates true investment value. Security analysts operate in three arenas, each reflecting a different set of goals and objectives. Investment banking and brokerage firms represent the "sell" side of security analysis. Their clients are fee and commission paying institutional and individual investors. Investment management organizations conduct security analysis for the portfolios they manage. Since portfolio managers purchase securities, they represent the "buy" side of the street. Finally, a number of investment publishing services provide security analysis for all investors subscribing to their reports. The most popular 10

investment services are available through Value Line Inc., Standard & Poor's, Moody's Investors Service, and Dun & Bradstreet.

Methodology and Procedure of Work There are two basic methodologies: fundamental analysis and technical analysis. In their own way, each approaches investment decisions from the top-down and from the bottom-up. THE TOP-DOWN APPROACH. The top-down approach, the traditional methodology, begins with a broad perspective and ends with a specific analysis of a stock or a bond. The top-down approach initially analyzes macroeconomic data, filters it into more specific sectors, and finally distills the results with respect to a specific security. Analysts determine the important economic conditions and forces at work and their potential impact on the markets. Analysts examine corporate profitability, the direction and magnitude of interest rates, money supply, fiscal policy, employment, migration, export/import trends, etc., to evaluate the future performance of individual economic sectors and industries. Security analysts also utilize the top-down approach to allocate available funds within portfolios between short-term and long-term investments, between risky and risk-free securities, and between stocks and bonds. Sector-to-sector and market-to-market comparisons purport to identify where investors should look for superior returns. Analysts recommend investing in favorable industries or sectors, and suggest specific stocks within each sector. THE BOTTOM-UP APPROACH. A major drawback to the top-down approach is the likelihood of overlooking certain stocks that offer significant investment opportunities but which are outside the favorable sectors. To remedy this, analysts also utilize the bottom-up approach which identifies superior performers without regard to industry. This approach identifies advantageous investments according to performance and financial criteria. The criteria are applicable across industry and sectors, establishing performance and financial benchmarks which companies must meet or exceed in order to be considered. 11

Analysts also develop criteria to separate the top performers by various degrees of risk, e.g., conservative versus aggressive. Once the screens have filtered out the appropriate securities, the analyst conducts a fundamental analysis of the company. FUNDAMENTAL ANALYSIS Fundamental analysts look for superior returns from securities that are mispriced by the market. To identify them the analyst engages in various calculations using data from financial statements and balance sheets to determine the future earnings and dividends of a company, the degree to which these exceed the expected average for the industry, and the potential for the stock to move closer to a correct or fair value. Fundamental analysts would recommend buying undervalued, or underpriced, stocks. When a stock is believed to be overvalued, the analyst would advise selling or taking a short position because the market would be expected to correct the price downward in the future.

THE OPERATING ENVIRONMENT. Some of the external conditions affecting a company's performance are: Demographic changes: sex, age, absolute numbers, location, population movements, educational preparation. Economic conditions: employment level, regional performance, wage levels, spending patterns, consumer debt, capital investment. Government fiscal policy and regulation spending levels, the magnitude of entitlements, debt, war and peace, tax policies, environmental regulations.

12

Competition: market penetration and position, market share, commodity, commodities marketing strategies, and niche products. Vendors: financial soundness, quality and quantity of product, R&D capabilities, alternative suppliers, just-in-time capabilities. Industry- and firm-specific characteristics important to the fundamental analyst are: profitability; market presence; productivity; product type, sales, and services; financial resources; physical facilities; research and development; quality of management. The analyst approaches these indicators in two ways: first, as trends within an industry, and secondly as features of a particular firm. To do this, analysts use a series of ratios constructed from the financial statements. Ratios represent the percentage or decimal relationship of one number to another. Ratios facilitate the use of comparative financial statements, which provide significant information about trends and relationships over two or more years. Analysts compare a company's ratios to industry ratios, as well as cross-sectionally to other companies. Structural analysis compares two financial statements in terms of the various items or groups of items within the same period. Time series analysis correlates ratios over time, measured in years or by quarters. Since ratios are relative measures, they furnish a common scale of measurement from which analysts construct historical averages. Thus, analysts are able to compare companies of different sizes and from different industries based on performance and financial condition by (a) establishing absolute standards, (b) examining averages, and (c) using trends to forecast future results. To increase predictability, the analyst considers the impact of external factors on internal trends. PIONEERS. In 1934 Benjamin Graham and David Dodd published Security Analysis. This book is considered the bible of fundamental practitioners. In the 1920s, Graham became a successful portfolio manager by stressing capital preservation by investing proportionately in high quality stocks and in low risk credit instruments. With Dodd, his student from UCLA, Graham laid out vigorous investment procedures in the book. Graham and Dodd primarily appraised stocks according to their earning power. They recommended an extensive list of financial ratios to measure a company's performance according to: Projected future earnings 13

Projected future dividends A method for valuing expected earnings The value of the asset In the belief that investors tended to overreact to near-term prospects, Graham and Dodd designed formulas to keep the disparity between P/E's for different companies within sharp focus. Analysts continue to apply these principles today. Analysis of Data Financial analysis is necessary in determining the future value of a company. Financial analysis concentrates on the condition of the financial statements: the income statement, the balance sheet, the statement of changes in shareholders' equity, and the funds flow statements. From these the analyst determines the values of the outstanding claims on the company's income. Financial analysts measure past performance, evaluate present conditions, and make predictions as to future performance. This information is important to investors looking for superior returns. Creditors use this information to determine the risk associated with the extension of credit. RATIO ANALYSIS. The most common method used by analysts is financial ratios. Composition ratios compare the size of the components of any accounting category with the total of that category, for example, the percentage of net income to net sales. Composition ratios: Indicate the size of each of the components relative to their total and to each other. Make historic comparisons and trending possible. Point to cause-and-effect components and their total. relationships between the individual

FUNDAMENTAL WEAKNESSES. Although widely used, financial analysis does have some fundamental weaknesses. Since it is based on data from financial reports, its findings 14

are subject to distortions resulting from inflation, wild business swings, changes in accounting practices, and undisclosed inner-workings of the firm. Management can manipulate important key ratios by changing inventory valuations, depreciation schedules, and expense recognition practices. Furthermore, since the financial statements are static, the analyst cannot account for the impact of seasonal variations. Finally, the ratios are meaningless unless compared to performance benchmarks. TECHNICAL ANALYSIS Technical analysis examines stock price trends in an attempt to predict future prices. Technical analysts believe that all the relevant information about economic fundamentals of an industry and of a stock are reflected in the direction and volume of prices. Therefore, technical analysts look to the past, for they believe that markets are cyclical, forming specific patterns, and these patterns repeat themselves over time. They further believe that it is only necessary to compare shortterm and intermediate price movements to long-term trends in order to predict market direction. Two major techniques form the basis of technical analysis: the study of key indicators, and the charting of market activity. KEY INDICATORS. Common key following: indicators utilized by technical analysts include the

Trading volume is based on supply-demand relationships and indicates market strength or weakness. Rising prices with increased buying generally signals uptrends. Decreasing prices with increasing demand, and increasing prices with decreasing volume, signal downtrends. Trading volume applies best to the short-term (three to nine months). Market breadth examines the activity of a broader range of securities than do highly publicized indices such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average. The breadth index is the net daily advances or declines divided by the amount of securities traded. The breadth index is calculated by either the number of securities, the dollar volume, or nominal volume. Breadth analysis concentrates on change rather than on level in order to evaluate the dispersion of a general movement in prices. The slope of the advance/decline line indicates the trend of the breadth index. Breadth analysis points to the prime turning points in bull and bear markets.

15

Confidence indices evaluate the trading patterns of bond investors who are regarded as more sophisticated and more well-informed that stock traders and, therefore, spot trends more quickly. Other confidence theories measure the sentiment among analysts themselves, the breadth trends in options and futures trading, and consumer confidence. Analysts consider these to have predictive value in the near and intermediate term. The put-call ratio divides the volume of puts outstanding by the volume of calls outstanding. Investors generally purchase the greatest number of puts around market bottoms when their pessimism peaks, thus indicating a turnaround. Call volume is greatest around market peaks, at the heights of investor enthusiasmalso indicating a market turn. The cash position of funds gives an indication of potential demand. Analysts examine the volume and composition of cash held by institutional investors, pension funds, mutual funds, and the like. Because fund managers are performance driven, analysts expect them to search out higher returns on large cash balances and, therefore, will invest more heavily in securities, driving prices higher. Short selling represents a bearish sentiment. Analysts in agreement with short sellers expect a downturn in the market. Analysts particularly watch the action of specialists who make a market in a specific stock. In addition, analysts look at odd-lot short sellers who indicate pessimism with increased activity. However, many technical analysts express a "contrarian" view regarding short sales. These analysts believe short sellers overreact and speculate because of the potential profits involved. In addition, to close their positions, short sellers will purchase the securities in the future, thus putting upward pressure on prices. Short selling analysis is based on month-to-month trends. Odd-lot theory follows the trends of transactions involving less than round lots (less than 100 shares). This theory rests on a contrarian opinion about small investors. The theory believes the small trader is right most of the time, and begins to sell into an upward trend. However, as the market continues to rise, the small investor re-enters the market as the sophisticated traders are bailing out in anticipation of a top and a pull back. Therefore, an increase in odd-lot trading signals a downturn in the market. Odd-lot indices divide (1) odd-lot purchases by odd-lot sales, (2) oddlot short sales by total odd-lot sales, and (3) total odd-lot volume (buys + sales) by round-lot volume. CHARTING. 16

Charting is useful in analyzing market conditions and price behavior of individual securities. Standard & Poor's Trendline is a well known charting service which provides data on companies. This data shows the trend of prices, insider sales, short sales, and trading volume over the intermediate and long-term. Analysts have plotted this data on graphs to form line, bar, and point-and-figure charts. Chart interpretation requires the ability to evaluate the meaning of the resulting formations in order to identify ranges in which to buy or sell. Charting assists in ascertaining major market downturns, upturns, and trend reversals. Analysts use moving averages to analyze intermediate and long-term stock movements. They predict the direction of prices by examining the trend in current prices relative to the long-term moving average. A moving-average depicts the underlying direction and degree of change. The relative strength of an individual stock price is a ratio of the average monthly stock price compared to the monthly average index of the total market or the stock's industry group. It informs the analysts of the relationship of specific price movements to an industry or the market in general. When investors favor specific stocks or industries, these will be relatively strong. Stocks that outperform the market trend on the upside may suddenly retreat when investors bail out for hotter prospects. Stocks that outperform in a declining market usually attract other investors and remain strong. As analysts construct charts, certain trends appear. These trends are characterized by a range of prices in which the stock trades. The lower end of the range forms a support base for the price. At that end a stock is a "good" buy and attracts additional investors, and thus forms a support level. As the price increases, a stock may become "unattractive" when compared to other stocks. Investors sell causing that upper limit to form a resistance level. Movements beyond the support and resistance levels require a fundamental change in the market and/or the stock. RANDOM WALK THEORIES Random-walk theorists do not believe in the cyclical nature of markets although they analyze the same data as do chartists. Random walk theory maintains that technical analysis is useless because past price and volume statistics do not contain any information by themselves that bode well for success. Random walkers believe choosing securities randomly will result in returns comparable to technical and fundamental analysis. 17

Through a series of illustrations, academicians in the 1960s and 1970s demonstrated that there is no basis in fact for technical analysis. They found that price movements were random and displayed no predictable pattern of movement, as did the Frenchman Louis Bachelier at the turn of the century. Therefore, prices have no predictive value. Since all the studies indicated randomness in price, the proponents of this hypothesis called it the "random walk theory." Random walkers use time-series models to relate efficient markets to the behavior of stock prices and investment returns. They believe that changes in prices are independent of new information entering the market, and that these prices changes are evenly distributed throughout the market. Since this means that the distribution of price changes is constant from one period to the next, investors are not able to identify "mispriced" securities in any consistent fashion. Experience and empirical evidence contradict this assumption, suggesting that the random walk properties of returns (or price changes) are too restrictive. Technicians maintain the validity of their practices especially with regards to the timing of investments. Since computer-based trading programs incorporate some timing technique into their matrix, intra-day trading has increasingly become characterized by dramatic movements in the indices. These movements represent a consensus among traders of the applicability of technical theories despite of the evidence of random walkers. A market driven by similarly configured indices, no matter what the basis, becomes more predictable over time. In practice, computer programs execute trades not only in anticipation of a market move, but to provide fund managers the opportunity to change positions ahead of the others. DOW THEORY Although Charles Dowpublisher of the Wall Street Journal was a fundamentalist, he published a series of articles which laid the foundation for William P. Hamilton's 1908 work that formalized the Dow Theory. Hamilton theorized that the stock market is the best gauge of financial and business activity because all relevant information is immediately discounted in the prices of stocks, as indexed by the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Dow Jones Transportation Average. Accordingly, both averages must confirm market direction because price trends in the overall market points to the termination of both bull and bear markets. Three movements are assumed to occur simultaneously: 18

A primary bull or bearish trend, typically lasting 28 to 33 months. A secondary trend goes counter to the primary trend, typically lasts three weeks to three months, and reflects a long-term primary movement. Day-to-day activity makes up the first two movements of the market, confirming the direction of the long-term primary trend. The primary trend must be supported by strong day-to-day activity to erase the effects of the secondary trend, otherwise, the market will begin to move in the opposite direction. If day-to-day activity supports the secondary trend, the market will soon reverse directions and develop a new primary trend. If the cyclical movements of the market averages increase over time, and the successive lows become higher, the market will trend upward. If the successive highs trend lower, and the successive low trend lower, then the market is in a downtrend. Computer programs have fully integrated Dow theory into their decision-making matrix. Portfolio investment 1. Passive investment for the sole-purpose of deriving income, as opposed to participating in the management of the investee firm under a direct investment. 2. Investment in an assortment or range of securities, or other types of investment vehicles, to spread the risk of possible loss due to below expectations performance of one or a few of them. Investment portfolio Pool of different investments by which an investor bets to make a profit (or income) while aiming to preserve the invested (principal) amount. These investments are chosen generally on the basis of different riskreward combinations: from 'low risk, low yield' (gilt edged) to 'high risk, high yield' (junk bonds) ones; or different types of income streams: steady but fixed, or variable but with a potential for growth.

Economic Definition of portfolio investment. Defined. Term portfolio investment Definition: The acquisition of financial assets (which includes stock, bonds, deposits, and currencies) from one country 19

in another country. In contrast to foreign direct investment, which is the acquisition of controlling interest in foreign firms and businesses, portfolio investment is foreign investment into the stock markets. Most economists consider foreign direct investment more useful than portfolio investment since this last one is generally regarded as temporal and can leave the foreign country at the first sign of trouble. Asset allocation - the way we divide our capital among different investment options - accounts for more than 90 per cent of your portfolio's overall return. Which is why it's so very important to get the asset allocation right in your investment portfolio. The portfolio's the thing Get used to the fact that, at any one time, a few parts of our portfolio will be doing terribly. Over a long enough time period, each and every component will have had a bad year or two. This is normal asset-class behavior and cannot be avoided. So, focus on the performance of the portfolio as a whole, not the individual parts. In asset allocation, job one is to pick an appropriate stock / bond mix This is determined primarily by our risk tolerance. Do not bite off more risk than we can chew - a classic beginner's mistake. Calmly and coolly planning for a market downturn is quite different from actually living through one, in the same way that crashing a flight simulator is different from crashing a real airplane. Time horizon is also important. Do not invest any money in stocks that you will need in less than five years, and do not invest more than half unless you will not need the money for at least a decade. Allocate our stocks widely among many different asset classes Our biggest exposure should be to the broad domestic stock market. Use small stocks, foreign stocks, and real estate investment trusts (REITs) in smaller amounts. It makes a difference where we put things Some asset classes, such as large foreign and domestic stocks, and domestic small stocks, are available in tax-efficient vehicles; put these in your taxable accounts. Other asset classes, particularly value stocks, REITs, and junk bonds, are highly tax-inefficient. Put these only in your tax-sheltered retirement accounts.

20

Don't rebalance portfolio too often. The benefit of rebalancing back to policy allocation is that it forces to sell high and buy low. Asset classes tend to trend up or down for up to a few years. Give this process a chance to work; We should not rebalance more often than once per year. These rules apply to tax-sheltered accounts. In taxable accounts, rebalance only with outflows, inflows, and mandatory distributions; here, the rebalancing benefit is usually outweighed by the tax consequences. Human beings tend to be most impressed with what has happened in the past several years and wrongly assume that it will continue forever. It never does. The fact that large U.S. growth stocks performed extremely well in the late 1990s does not make it more likely that this will continue; in fact, it makes it slightly less likely. The performance of different kinds of stocks and bonds is best evaluated only over the long haul. Investors like to have fashionable portfolios, invested in the era's most exciting technologies. Resist the temptation. There is an inverse correlation between an investment's entertainment value and its expected return; IPOs, on average, have low returns, and boring stocks tend to reward the most. An asset allocation that maximizes chances of getting rich also maximizes your chances of becoming poor.Best chance of making ourself fabulously wealthy through investing is to buy a few small stocks with good growth possibilities; Of course, it is far more likely that we will lose most of our money this way. On the other hand, although we cannot achieve extremely high returns with a diversified portfolio, it is the best way to avoid a retirement diet of cat food. Knowledge of financial history is the most potent weapon in the investor's armamentarium. Since the dawn of stock broking in the seventeenth century, every generation has experienced its own version of tech bust. The recent dot-com catastrophe was just one more act in finance's longest running comedy. Be able to say to yourself, 'I've seen this movie before, and I think I know how it ends.' The only thing that's new is the history you haven't read. A portfolio of 15 to 30 stocks does not provide adequate diversification The myth that it does results from a misinterpretation of modern financial theory. While it is true that a 30-stock portfolio has no more short-term volatility than the market, there is more to risk than day-today fluctuations. The real risk is not that short-term volatility will be 21

too high, but that long-term return will be too low. The only way of minimizing this risk is to own thousands of stocks in many nations. Or a few index funds. Investment Management: The professional management of assets, such as real estate, and securities, such as equities, bond and other debt instruments, is called investment management. Investment management services are sought by investors, which could be companies, banks, insurance firms or individuals, with the purpose of meeting stated financial goals. The need for investment management arises due to: The existence of a large number of complex financial products Financial market volatility Changes in regulatory requirements Every individual practices investment management to some degree, including budgeting, saving, investing and spending. However, an investment manager is one who specializes in placing money in diverse instruments in order to accomplish predetermined goals. Investment managers are also widely known as fund managers. Investment managers may specialize in advisory or discretionary management. When an investment manager merely offers suggestions regarding where to invest money and when to sell securities, the practice is known as advisory investment management. When an investment manager can take action in managing portfolios without requiring client approval, it is called "discretionary" investment management. Investment management is often used synonymously with fund management. Moreover, terms like asset management, wealth management and portfolio management are used, with a thin line differentiating them. Asset management is often used for the management of collective investments, which refers to investing money on behalf of a large group of clients in a wide range of investment options. An example of this is mutual funds. Investment management that involves managing the investments of high net worth individuals is often referred to as wealth management. Asset management and wealth management are also called portfolio management. The process of investment management involves the following: Setting investment objectives: Investment goals are different for individuals, financial institutions, banks, insurance companies and 22

pension and mutual funds. For instance, the objective of a bank could be to achieve a minimum interest spread, while that for an individual investor could be to increase return on investment. Formulating the investment plan: After setting the objective, the investment plan is formulated based on investor-related constraints, such as financial capacity and risk profile, as well as environmental constraints, such as government regulations, market conditions and the state of the economy. Establishing the portfolio strategy: Based on the objectives and constraints, the ideal mix of asset classes is identified. These asset classes could include equities, fixed income securities, foreign securities, debt, real estate and/or currencies. Selecting the assets: This involves selecting the individual options within the wide asset classes. Measuring and evaluating performance: Investment management is an ongoing process. It is critical to consistently evaluate the performance of the portfolio and to improve it continuously

A logical starting point is to create a product strategy - markets, customers, products, strategy approach, competitive emphasis, etc. The second step is to understand the budget or resources available to balance the portfolio against. Third, each project must be assessed for profitability (rewards), investment requirements (resources), risks, and other appropriate factors. The weighting of the goals in making decisions about products varies from company. But organizations must balance these goals: risk vs. profitability, new products vs. improvements, strategy fit vs. reward, market vs. product line, long-term vs. short-term. Several types of techniques have been used to support the portfolio management process: Heuristic models Scoring techniques Visual or mapping techniques

23

The earliest Portfolio Management techniques optimized projects' profitability or financial returns using heuristic or mathematical models. However, this approach paid little attention to balance or aligning the portfolio to the organization's strategy. Scoring techniques weight and score criteria to take into account investment requirements, profitability, risk and strategic alignment. The shortcoming with this approach can be an over emphasis on financial measures and an inability to optimize the mix of projects. Mapping techniques use graphical presentation to visualize a portfolio's balance. These are typically presented in the form of a two-dimensional graph that shows the tradeoff's or balance between two factors such as risks vs. profitability, marketplace fit vs. product line coverage, financial return vs. probability of success, etc In finance, a portfolio is a collection of investments held by an institution or an individual. Holding a portfolio is a part of an investment and risk-limiting strategy called diversification. By owning several assets, certain types of risk (in particular specific risk) can be reduced. The assets in the portfolio could include bank accounts, stocks, bonds, options, warrants, gold certificates, real estate, futures contracts, production facilities, or any other item that is expected to retain its value. In building up an investment portfolio a financial institution will typically conduct its own investment analysis, while a private individual may make use of the services of a financial advisor or a financial institution which offers portfolio management services. Portfolio management involves deciding what assets to include in the portfolio, given the goals and risk tolerance of the portfolio owner. Selection involves deciding which assets to acquire/divest, how many to acquire/divest, and when to acquire/divest them. These decisions always involve some sort of performance measurement, most typically the expected return on the portfolio, and the risk associated with this return (e.g., the expected standard deviation of the expected return). However, due to the almost-complete uncertainty of future values, this performance measurement is often done on a casual qualitative basis, rather than a precise quantitative basis (which would give a false sense of precision). Typically the expected return from portfolios of different asset bundles are compared. The unique goals and circumstances of the investor must also be considered. Some investors are more risk averse than others. Portfolio formation 24

Many strategies have been developed to form a portfolio; among them: equally-weighted portfolio capitalization-weighted portfolio price-weighted portfolio optimal portfolio (for which Risk-Adjusted Return is highest)

The chart shown above provides a graphical view of the project portfolio risk-reward balance. It is used to assure balance in the portfolio of projects - neither too risky or conservative and appropriate levels of reward for the risk involved. The horizontal axis is Net Present Value, the vertical axis is Probability of Success. The size of the bubble is proportional to the total revenue generated over the lifetime sales of the product. While this visual presentation is useful, it can't prioritize projects. Therefore, some mix of these techniques is appropriate to support the 25

Portfolio Management Process. This mix is often dependent upon the priority of the goals.

Findings, Inferences and Recommendations Our recommended approach is to start with the overall business plan that should define the planned level of R&:D investment, resources (e.g., headcount, etc.), and related sales expected from new products. With multiple business units, product lines or types of development, we recommend a strategic allocation process based on the business plan. This strategic allocation should apportion the planned R&D investment into business units, product lines, markets, geographic areas, etc. It may also breakdown the R&D investment into types of development, e.g., technology development, platform development, new products, and upgrades/enhancements/line extensions, etc. Once this is done, then a portfolio listing can be developed including the relevant portfolio data. We favor use of the development productivity index (DPI) or scores from the scoring method. The development productivity index is calculated as follows: (Net Present Value x Probability of Success) / Development Cost Remaining. It factors the NPV by the probability of both technical and commercial success. By dividing this result by the development cost remaining, it places more weight on projects nearer completion and with lower uncommitted costs. The scoring method uses a set of criteria (potentially different for each stage of the project) as a basis for scoring or evaluating each project. An example of this scoring method is shown with the worksheet below.

26

Weighting factors can be set for each criteria. The evaluators on a Product Committee score projects (1 to 10, where 10 is best). The worksheet computes the average scores and applies the weighting factors to compute the overall score. The maximum weighted score for a project is 100. This portfolio list can then be ranked by either the development priority index or the score. An example of the portfolio list is shown below and the second illustration shows the category summary for the scoring method.

27

Once the organization has its prioritized list of projects, it then needs to determine where the cutoff is based on the business plan and the planned level of investment of the resources available. This subset of the high priority projects then needs to be further analyzed and checked. The first step is to check that the prioritized list reflects the planned 28

breakdown of projects based on the strategic allocation of the business plan. Pie charts such as the one below can be used for this purpose.

Other factors can also be checked using bubble charts. For example, the risk-reward balance is commonly checked using the bubble chart shown earlier. A final check is to analyze product and technology roadmaps for project relationships. For example, if a lower priority platform project was omitted from the portfolio priority list, the subsequent higher priority projects that depend on that platform or platform technology would be impossible to execute unless that platform project were included in the portfolio priority list. An example of a roadmap is shown below.

29

This overall portfolio management process is shown in the following diagram.

30

Finally, this balanced portfolio that has been developed is checked against the business plan as shown below to see if the plan goals have been achieved - projects within the planned R&D investment and resource levels and sales that have met the goals. 31

With the significant investments required to develop new products and the risks involved, Portfolio Management is becoming an increasingly important tool to make strategic decisions about product development and the investment of company resources. In many companies, current year revenues are increasingly based on new products developed in the last one to three years. Therefore, these portfolio decisions are the basis of a company's profitability and even its continued existence over the next several years. Product portfolio strategy Introduction 32

The business portfolio is the collection of businesses and products that make up the company. The best business portfolio is one that fits the company's strengths and helps exploit the most attractive opportunities. The company must: (1) Analyse its current business portfolio and decide which businesses should receive more or less investment, and (2) Develop growth strategies for adding new products and businesses to the portfolio, whilst at the same time deciding when products and businesses should no longer be retained. Methods of Portfolio Planning The two best-known portfolio planning methods are from the Boston Consulting Group (the subject of this revision note) and by General Electric/Shell. In each method, the first step is to identify the various Strategic Business Units ("SBU's") in a company portfolio. An SBU is a unit of the company that has a separate mission and objectives and that can be planned independently from the other businesses. An SBU can be a company division, a product line or even individual brands - it all depends on how the company is organised. The Boston Consulting Group Box ("BCG Box")

Using the BCG Box (an example is illustrated above) a company classifies all its SBU's according to two dimensions:

33

On the horizontal axis: relative market share - this serves as a measure of SBU strength in the market On the vertical axis: market growth rate - this provides a measure of market attractiveness By dividing the matrix into four areas, four types of SBU can be distinguished: Stars - Stars are high growth businesses or products competing in markets where they are relatively strong compared with the competition. Often they need heavy investment to sustain their growth. Eventually their growth will slow and, assuming they maintain their relative market share, will become cash cows. Cash Cows - Cash cows are low-growth businesses or products with a relatively high market share. These are mature, successful businesses with relatively little need for investment. They need to be managed for continued profit - so that they continue to generate the strong cash flows that the company needs for its Stars. Question marks - Question marks are businesses or products with low market share but which operate in higher growth markets. This suggests that they have potential, but may require substantial investment in order to grow market share at the expense of more powerful competitors. Management have to think hard about "question marks" - which ones should they invest in? Which ones should they allow to fail or shrink? Dogs - Unsurprisingly, the term "dogs" refers to businesses or products that have low relative share in unattractive, low-growth markets. Dogs may generate enough cash to break-even, but they are rarely, if ever, worth investing in. Using the BCG Box to determine strategy Once a company has classified its SBU's, it must decide what to do with them. In the diagram above, the company has one large cash cow (the size of the circle is proportional to the SBU's sales), a large dog and two, smaller stars and question marks. Conventional strategic thinking strategies for each SBU: suggests there are four possible

(1) Build Share: here the company can invest to increase market share (for example turning a "question mark" into a star) 34

(2) Hold: here the company invests just enough to keep the SBU in its present position (3) Harvest: here the company reduces the amount of investment in order to maximise the short-term cash flows and profits from the SBU. This may have the effect of turning Stars into Cash Cows. (4) Divest: the company can divest the SBU by phasing it out or selling it - in order to use the resources elsewhere (e.g. investing in the more promising "question marks").

The BCG Matrix method is the most well-known portfolio management tool. It is based on product life cycle theory. It was developed in the early 70s by the Boston Consulting Group. The BCG Matrix can be used to determine what priorities should be given in the product portfolio of a business unit. To ensure long-term value creation, a company should have a portfolio of products that contains both high-growth products in need of cash inputs and low-growth products that generate a lot of cash. The Boston Consulting Group Matrix has 2 dimensions: market share and market growth. The basic idea behind it is: if a product has a bigger market share, or if the product's market grows faster, it is better for the company.

35

The four segments of the BCG Matrix Placing products in the BCG matrix provides 4 categories in a portfolio of a company: Stars (high growth, high market share) Stars are using large amounts of cash. Stars are leaders in the business. Therefore they should also generate large amounts of cash. Stars are frequently roughly in balance on net cash flow. However if needed any attempt should be made to hold market share in Stars, because the rewards will be Cash Cows if market share is kept. Cash Cows (low growth, high market share) Profits and cash generation should be high. Because of the low growth, investments which are needed should be low. Cash Cows are often the stars of yesterday and they are the foundation of a company. 36

Dogs (low growth, low market share) Avoid and minimize the number of Dogs in a company. Watch out for expensive rescue plans. Dogs must deliver cash, otherwise they must be liquidated. Question Marks (high growth, low market share) Question Marks have the worst cash characteristics of all, because they have high cash demands and generate low returns, because of their low market share. If the market share remains unchanged, Question Marks will simply absorb great amounts of cash. Either invest heavily, or sell off, or invest nothing and generate any cash that you can. Increase market share or deliver cash. the BCG Matrix and one size fits all strategies The BCG Matrix method can help to understand a frequently made strategy mistake: having a one size fits all strategy approach, such as a generic growth target (9 percent per year) or a generic return on capital of say 9,5% for an entire corporation. In such a scenario: Cash Cows Business Units will reach their profit target easily. Their management have an easy job. The executives are often praised anyhow. Even worse, they are often allowed to reinvest substantial cash amounts in their mature businesses. Dogs Business Units are fighting an impossible battle and, even worse, now and then investments are made. These are hopeless attempts to "turn the business around". As a result all Question Marks and Stars receive only mediocre investment funds. In this way they can never become Cash Cows. These inadequate invested sums of money are a waste of money. Either these SBUs should receive enough investment funds to enable them to achieve a real market dominance and become Cash Cows (or Stars), or otherwise companies are advised to disinvest. They can then try to get any possible cash from the Question Marks that were not selected. 37

Other uses and benefits of the BCG Matrix If a company is able to use the experience curve to its advantage, it should be able to manufacture and sell new products at a price that is low enough to get early market share leadership. Once it becomes a star, it is destined to be profitable. BCG model is helpful for managers to evaluate balance in the firms current portfolio of Stars, Cash Cows, Question Marks and Dogs. BCG method is applicable to large companies that seek volume and experience effects. The model is simple and easy to understand. It provides a base for management to decide and prepare for future actions. Limitations of the BCG Matrix Some limitations of the Boston Consulting Group Matrix include: It neglects the effects of synergy between business units. High market share is not the only success factor. Market growth is not the only indicator for attractiveness of a market. Sometimes Dogs can earn even more cash as Cash Cows. The problems of getting data on the market share and market growth. There is no clear definition of what constitutes a "market". A high market share does not necessarily lead to profitability all the time. The model uses only two dimensions market share and growth rate. This may tempt management to emphasize a particular product, or to divest prematurely. A business with a low market share can be profitable too. The model neglects small competitors that have fast growing market shares. 38

Portfolio (BCG) Matrix Using the Product Portfolio Matrix approach, a company classified all its SBUs or Products/Markets according to Growth-Share Matrix. Therefore, it is best describe as Portfolio planning model.

BCG Matrix In this Matrix Quadrants, the plate is divided 4 categories named A. Star B. Cash Cow C. Question Mark D. Dog The division is based on Market Share and Growth rate. A brief discussion comes follow: A. Star: Leader [i.e. high market share] of high growth market is called star. These SBUs are net user of cash, because they always require heavy investment to finance rapid growth and to sustain market share. When the product comes to mature stage, then the growth slow down and they turn to cash cow. 39

B. Cash Cow: Cash cows are low growth but high market share (Market leader) businesses or products. Their high earnings, coupled with their depreciation, represent high cash inflows and they need very little in the way of reinvestment. And thus, they are the net provider of cash. Surplus cash are used for Research and Development and to support other SBUs that need investment. C. Question mark: Products in a growth market with low market share are categorized as Question Mark. Because of growth, these SBUs require a lot of cash to hold their market share and let alone to increase it. If nothing is done to increase the market share, a Question mark will simply absorb large amount of cash in the short run and later, as growth slow down, become a dog. Thus, unless something is done to change its perspective, it becomes a cash trap. Management has to decide which question marks should try to build into stars and which should be phased out. D. Dog: Dog are low growths, low market generate enough cash to maintain themselves, large source Most often case, it should be liquidate and try for investment. share SBUs. They may but do not promise to be of cash. with Question mark SBUs

Market Growth Rate and Relative Market Share play important roll in BCG Matrix. Market Growth Rate is the measure of industry attractiveness and Relative Market Share is the measure of Competitive advantage. Therefore, these two are most important factors to consider organizations profitability and strategic plan. Limitations: Though the Product Portfolio Matrix is well known to ease the way of portfolio analysis, It has several limitations also. Here some of limitations are narrate briefly: A. High Market Share is not the only factor to measure competitive advantage. Similarly, Market growth rate is not the only factor to measure industry attractiveness. B. Sometime a dog SBU used as synergy to other SBUs. i.e. a dog may help other SBUs to gain a competitive advantage. 40

C. Sometimes Dogs of a huge market can earn even more cash as Cash Cows. Though it has some limitations, BCG matrix is a very effective tool to viewing a corporations business portfolio at a glance. And also helpful to the decision making process for allocating corporate resources.

10 rules for a profitable investment portfolio Asset allocation - the way you divide your capital among different investment options - accounts for more than 90 per cent of your portfolio's overall return. Which is why it's so very important to get the asset allocation right in your investment portfolio.

The portfolio's the thing Get used to the fact that, at any one time, a few parts of your portfolio will be doing terribly. Over a long enough time period, each and every component will have had a bad year or two. This is normal asset-class behaviour and cannot be avoided. So, focus on the performance of the portfolio as a whole, not the individual parts. In asset allocation, job one is to pick an appropriate stock / bond mix This is determined primarily by your risk tolerance. Do not bite off more risk than you can chew - a classic beginner's mistake. Calmly and coolly planning for a market downturn is quite different from actually living through one, in the same way that crashing a flight simulator is different from crashing a real airplane. Time horizon is also important. Do not invest any money in stocks that you will need in less than five years, and do not invest more than half unless you will not need the money for at least a decade. Allocate your stocks widely among many different asset classes Your biggest exposure should be to the broad domestic stock market. Use small stocks, foreign stocks, and real estate investment trusts (REITs) in smaller amounts. 41

It makes a difference where we put things. Some asset classes, such as large foreign and domestic stocks, and domestic small stocks, are available in tax-efficient vehicles; put these in your taxable accounts. Other asset classes, particularly value stocks, REITs, and junk bonds, are highly tax-inefficient. Put these only in your tax-sheltered retirement accounts. Don't rebalance your portfolio too often The benefit of rebalancing back to your policy allocation is that it forces you to sell high and buy low. Asset classes tend to trend up or down for up to a few years. Give this process a chance to work; you should not rebalance more often than once per year. These rules apply to tax-sheltered accounts. In taxable accounts, rebalance only with outflows, inflows, and mandatory distributions; here, the rebalancing benefit is usually outweighed by the tax consequences. The recent past is out to get you Human beings tend to be most impressed with what has happened in the past several years and wrongly assume that it will continue forever. It never does. The fact that large U.S. growth stocks performed extremely well in the late 1990s does not make it more likely that this will continue; in fact, it makes it slightly less likely. The performance of different kinds of stocks and bonds is best evaluated only over the long haul. If you want to be entertained, take up sky diving Investors like to have fashionable portfolios, invested in the era's most exciting technologies. Resist the temptation. There is an inverse correlation between an investment's entertainment value and its expected return; IPOs, on average, have low returns, and boring stocks tend to reward the most. An asset allocation that maximizes your chances of getting rich also maximizes your chances of becoming poor Your best chance of making yourself fabulously wealthy through investing is to buy a few small stocks with good growth possibilities; Of course, it is far more likely that you will lose most of your money this way. On the other hand, although you cannot achieve extremely high returns with a diversified portfolio, it is the best way to avoid a retirement diet of cat food. 42

43

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- 2CEXAM Mock Question Licensing Examination Paper 7Dokument10 Seiten2CEXAM Mock Question Licensing Examination Paper 7Tsz Ngong Ko100% (1)

- Trading Digital Financial AssetsDokument31 SeitenTrading Digital Financial AssetsArmiel DwarkasingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suggested Day Trading Plan - Fibonacciqueen: 8 Ema Crosses Above The 34 Ema and A Prior Swing High Is Taken OutDokument2 SeitenSuggested Day Trading Plan - Fibonacciqueen: 8 Ema Crosses Above The 34 Ema and A Prior Swing High Is Taken Outbrent100% (1)

- FRM Study PlanDokument4 SeitenFRM Study PlanMUKESH KUMARNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1099-b Whfit FormDokument6 Seiten1099-b Whfit FormYarod EL100% (4)

- BiofuelscanDokument15 SeitenBiofuelscanSAMYAK PANDEYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Date Settlement Price RM Per Ton Palm Oil Farmer (Short, RM) Balance (RM) Cooking Oil Factory (Long, RM) Balance (RM)Dokument2 SeitenDate Settlement Price RM Per Ton Palm Oil Farmer (Short, RM) Balance (RM) Cooking Oil Factory (Long, RM) Balance (RM)Abdul Aziz Al-BloshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recommendations of Narsimha CommitteeDokument10 SeitenRecommendations of Narsimha CommitteePrathamesh DeoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smart Money? The Forecasting Ability of CFTC Large Traders: by Dwight R. Sanders, Scott H. Irwin, and Robert MerrinDokument21 SeitenSmart Money? The Forecasting Ability of CFTC Large Traders: by Dwight R. Sanders, Scott H. Irwin, and Robert MerrinPerfect SebokeNoch keine Bewertungen

- OptionsDokument11 SeitenOptionsapi-3770121Noch keine Bewertungen

- 130 - Capital MarketDokument236 Seiten130 - Capital MarketShikha Arora100% (2)

- Datascope Reference DataDokument3 SeitenDatascope Reference DataGurupraNoch keine Bewertungen