Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

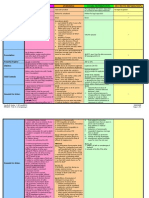

LegRes Case Digests

Hochgeladen von

roxie_mercadoOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

LegRes Case Digests

Hochgeladen von

roxie_mercadoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

In re: Cunanan, 94 Phil.

534 (1954) FACTS OF THE CASE: In the manner of the petitions for Admission to the Bar of unsuccessful candidates of 1946 to 1953; Albino Cunananet. al petitioners. In recent years few controversial issues have aroused so much public interest and concern as R.A. 972 popularly known as the Bar Flunkers Act of 1953. Generally a candidate is deemed passed if he obtains a general ave of 75% in all subjects w/o falling below 50% in any subject, although for the past few exams the passing grades were changed depending on the strictness of the correcting of the bar examinations (1946- 72%, 1947- 69%, 1948- 70% 1949-74%, 1950-1953 75%). Believing themselves to be fully qualified to practice law as those reconsidered and passed by the S.C., and feeling that they have been discriminated against, unsuccessful candidates who obtained averages of a few percentages lower than those admitted to the bar went to congress for, and secured in 1951 Senate Bill no. 12, but was vetoed by the president after he was given advise adverse to it. Not overriding the veto, the senate then approved senate bill no. 372 embodying substantially the provisions o the f vetoed bill. The bill then beca me law on June 21, 1953 Republic Act 972 has for its object, according to its author, to admit to the Bar those candidates who suffered from insufficiency of reading materials and inadequate preparations. By and large, the law is contrary to public intere since it qualifies 1,094 law st graduates who had inadequate preparation for the practice of law profession, as evidenced by their failure in the exams. ISSUES OF THE CASE:

Due to the far reaching effects that this law would have on the legal profession and the administration of justice, the S.C. would seek to know if it is CONSTITUTIONAL.

y y y y

An adequate legal preparation is one of the vital requisites for the practice of the law that should be developed constantly and maintained firmly. The Judicial system from which ours has been derived, the act of admitting, suspending, disbarring, and reinstating attorneys at law in the practice of the profession is concededly judicial. The Constitution, has not conferred on Congress and the S.C. equal responsibilities concerning the admission to the practice of law. The primary power and responsibility which the constitution recognizes continue to reside in this court Its retroactivity is invalid in such a way, that what the law seeks to cure are not the rules set in place by the S.C. but the lack of will or the defect in judgment of the court, and this power is not included in the power granted by the Const. to Congress, it lies exclusively w/in the judiciary. Reasons for Unconstitutionality: There was a manifest encroachment on the constitutional responsibility of the Supreme Court. It is in effect a judgment revoking the resolution of the court, and only the S.C. may revise or alter them, in attempting to do so R.A. 972 violated the Constitution. That congress has exceeded its power to repeal, alter, and supplement the rules on admission to the bar (since the rules made by congress must elevate the profession, and those rules promulgated are considered the bare minimum.) It is a class legislation Art. 2 of R.A. 972 is not embraced in the title of the law, contrary to what the constitution enjoins, and being inseparable from the provisions of art. 1, the entire law is void. HELD: Under the authority of the court:

1. 2. 3. 4. 5.

1. 2.

That the portion of art. 1 of R.A. 972 referring to the examinations of 1946 to 1952 and all of art. 2 of the said law are unconstitutional and therefore void and w/o force and effect. The part of ART 1 that refers to the examinations subsequent to the approval of the law (1953- 1955) is valid and shall continue in force. (those petitions by the candidates who failed the bar from 1946 to 1952 are denied, and all the candidates who in the examination of 1953 obtained a GEN Ave. of 71.5% w/o getting a grade of below 50% in any subject are considered as having passed whether they have filed petitions for admissions or not.

Agustin v. Edu, 88 SCRA 195 (1979) ;Agustin is the owner of a Volkswagen Beetle Car. He is assailing the validity of Letter of Instruction No 229 which requires all motor vehicles to have early warning devices particularly to equip them with a pair of reflectorized triangular early warning devices. Agustin is arguing that this order is unconstitutional, harsh, cruel and unconscionable to the motoring public. Car are s already equipped with blinking lights which is already enough to provide warning to other motorists. And that the mandate to compel motorists to buy a set of reflectorized early warning devices is redundant and would only make manufacturers and deale rs instant millionaires. ISSUE: Whether or not the said is EO is valid. HELD: Such early warning device requirement is not an expensive redundancy, nor oppressive, for car owners whose cars are already equipped with 1) blinking-lights in the fore and aft of said motor vehicles, 2) battery-powered blinking lights inside motor vehicles, 3) built-in reflectorized tapes on front and rear bumpers of motor vehicles, or 4) well-lighted two (2) petroleum lamps (the Kinke) . . . because: Being universal among the signatory countries to the said 1968 Vienna Conventions, and visible even

under adverse conditions at a distance of at least 400 meters, any motorist from this country or from any part of the world, who sees a reflectorized rectangular early warning device installed on the roads highways or expressways, will conclude, without , thinking, that somewhere along the travelled portion of that road, highway, or expressway, there is a motor vehicle which is stationary, stalled or disabled which obstructs or endangers passing traffic. On the other hand, a motorist who sees any of the aforementioned other built-in warning devices or the petroleum lamps will not immediately get adequate advance warning because he will still think what that blinking light is all about. Is it an emergency vehi le? Is it a law enforcement car? Is it an ambulance? c Such confusion or uncertainty in the mind of the motorist will thus increase, rather than decrease, the danger of collision. The Letter of Instruction in question was issued in the exercise of the police power. That is conceded by petitioner and is the main reliance of respondents. It is the submission of the former, however, that while embraced in such a category, it has offended against the due process and equal protection safeguards of the Constitutio although the latter point was mentioned only in n, passing. The broad and expansive scope of the police power which was originally identified by Chief Justice Taney of the American Supreme Court in an 1847 decision, as nothing more or less than the powers of government inherent in every sovereignty was stressed in the aforementioned case of Edu v. Ericta thus: Justice Laurel, in the first leading decision after the Constitution came into force, Calalang v. Williams, identified police power with state authority to enact legislation that may interfere with personal liberty or property in order to promote the general welfare. Persons and property could thus be subjected to all kinds of restraints and burdens in order to secure the general comfort, health and prosperity of the state. Shortly after independence in 1948, Primicias v. Fugoso reiterated the doctrine, such a competence being referred to as the power to prescribe regulations to promote the health, morals, peace, education, good order or safety, and general welfare of the people. The concept was set forth in negative terms by Justice Malcolm in a pre-Commonwealth decision as that inherent and plenary power in the State which enables it to prohibit all things hurtful to the comfort, safety and welfare of society. In that sense it could be hardly distinguishable as noted by this Court in Morfe v. Mutuc with the totality of legislative power. It is in the above sense the greatest and most powerful attribute of government. It is, to quote Justice Malcolm anew, the most essential, insistent, and at least illimitable powers, extending as Justice Holmes aptly pointed out to all the great public needs. Its scope, ever expanding to meet the exigencies of the times, even to anticipate the future where it could be done, provides enough room for an efficient and flexible response to conditions and circumstances thus assuring the greatest benefits. In the language of Justice Cardozo: Needs that were narrow or parochial in the past may be interwoven in the present with the well-being of the nation. What is critical or urgent changes with the time. The police power is thus a dynamic agency, suitably vague and far from precisely defined, rooted in the conception that men in organizin the g state and imposing upon its government limitations to safeguard constitutional rights did not intend thereby to enable an individual citizen or a group of citizens to obstruct unreasonably the enactment of such salutary measures calculated to insure communal peace, safety, good order, and welfare.

It was thus a heavy burden to be shouldered by petitioner, compounded by the fact that the particular police power measure challenged was clearly intended to promote public safety. It would be a rare occurrence indeed for this Court to invalidate a legislative or executive act of that character. None has been called to our attention, an indication of its being non -existent. The latest decision in point, Edu v. Ericta, sustained the validity of the Reflector Law, an enactment conceived with the same end in view. Calalang v. Williams found nothing objectionable in a statute, the purpose of which was: To promote safe transit upon, and avoid obstruction on roads and streets designated as national roads . . . As a matter of fact, the first law sought to be nullified after the effectivity of the 1935 Constitution, the National Defense Act, with petitioner failing in his quest, was likewise prompted by the imperative demands of public safety. Victorias Milling Co., Inc. v. Social Security Commissions 4 SCRA 627 (1962)

Facts: On October 15, 1958, the Social Security Commission issued its Circular No. 22 of the following tenor: "Effective November 1, 1958, all Employers in computing the premiums due the System, will take in...to consideration and include in the E mployee's remuneration all bonuses and overtime pay, as well as the cash value of other media of remuneration. All these will comprise the Employee's remuneration or earnings, upon which the 3-1/2% and 2-1/2% contributions will be based, up to a maximum of P500 for any one month." Petitioner Victorias Milling Company, Inc. wrote the Social Security Commission in effect protesting against the circular as contradictory to a previous Circular No. 7, dated October 7, 1957 expressly excluding overtime pay and bonus in the computation of the employers' and employees' respective monthly premium contributions. Moreover, it contended that due notice via publica tion was not complied with. Issue: (1) Whether or not Circular No. 22 is a rule or regulation, as contemplated in Section 4(a) of Republic Act 1161 empowering the Social Security Commission "to adopt, amend and repeal subject to the approval of the President such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the provisions and purposes of this Act." Held: It will thus be seen that whereas prior to the amendment, bonuses, allowances, and overtime pay given in addition to the regular or base pay were expressly excluded, or exempted from the definition of the term "compensation", such exemption or exclusion was deleted by the amendatory law. It thus became necessary for the Social Security Commission to interpret the effect of such deletion or elimination. Circular No. 22 was, therefore, issued to apprise those concerned of the interpretation or understanding of the Commission, of the law as amended, which it was its duty to enforce. It did not add any duty or detail that was not already in the law as amended. It merely stated and circularized the opinion of the Commission as to how the law should be construed.

National Federation of Sugar Workers vs. Ovejera GR No. L-59743, May 31, 1982 ; 114 SCRA 354 PLANA, J: FACTS: National Federation of Sugar Workers (NFSW) has concluded with Central Azucarera de la Carlota (CAC) a CBA effective February 16, 1981 to February 15, 1984 which provided that the parties agree to maintain the present practice on the grant of Christmas bonus, milling bonus, and amelioration bonus to the extent as the latter is required by law. The Christmas and millng i bonuses amount to 1 months' salary. On November 28, 1981, NFSW struck allegedly, to compel the payment of the 13th month pay under PD 851, in addition to the Christmas, milling and amelioration bonuses being enjoyed by CAC workers. On January 22, 1982, NFSW filed with the Ministry of Labor and Employment (MOLE) a notice of strike based on non-payment of the 13th month pay. Six days after, NFSW struck. One day after the commencement of the strike, a report of the strike-vote was filed by NFSW5 with MOLE. CAC filed a petition with the Regional Arbitration Branch of MOLE to declare the strike illegal, principally for being violative of BP 130, that is, the strike was declared before the expiration of the 15-day cooling- off period for ULP strikes, and the strike was staged before the lapse of seven days from the submission to MOLE of the result of the strike-vote After the submission of position papers and hearing, Labor Arbiter Ovejara declared the strike illegal. On February 26, 1982, the NFSW, by passing the NLRC filed the instant Petition for prohibition. ISSUE: Whether or not the strike declared by NFSW is illegal, the resolution of which mainly depends on the mandatory or directory character of the cooling-off period and the 7-day strike ban after report to MOLE of the result of a strike-vote, as prescribed in the Labor Code. HELD: When the law says "the labor union may strike" should the dispute "remain unsettled until the lapse of the requisite number o days f (cooling-off period) from the filing of the notice," the unmistakable implication is that the union may not strike before the lapse of the cooling-off period. Similarly, the mandatory character of the 7-day strike ban after the report on the strike-vote is manifest in the provision that "in every case," the union shall furnish the MOLE with the results of the voting "at least seven (7) days before the intended strike, subject to the (prescribed) cooling-off period." It must be stressed that the requirements of cooling-off period and 7day strike ban must both be complied with, although the labor union may take a strike vote and report the same within the statutory cooling-off period. If only the filing of the strike notice and the strike-vote report would be deemed mandatory, but not the waiting periods so specifically and emphatically prescribed by law, the purposes for which the filing of the strike notice and strike -vote report is required would not be achieved, as when a strike is declared immediately after a strike notice is served, or when as in the instant case the strike-vote report is filed with MOLE after the strike had actually commenced Such interpretation of the law ought not and cannot be countenanced. It would indeed be self-defeating for the law to imperatively require the filing on a strike notice and strikevote report without at the same time making the prescribed waiting periods mandatory. Floresca v. Philex Mining Company, 135 SCRA 141 (1985) SC Cannot Legislate - Exception Floresca et al are the heirs of the deceased employees of Philex Mining Corporation (hereinafter referred to as Philex), who, while working at its copper mines underground operations at Tuba, Benguet on June 28, 1967, died as a result of the cave-in that buried them in the tunnels of the mine. Specifically, the complaint alleges that Philex, in violation of government rules and regulations, negligently and deliberately failed to take the required precautions for the protection of the lives of its men working under round. g Floresca et al moved to claim their benefits pursuant to the Workmens Compensation Act before the Workmens Compensation Commission. They also petitioned before the regular courts and sue Philex for additional damages. Philex invoked that they ca no n longer be sued because the petitioners have already claimed benefits under the WCA. ISSUE: Whether or not Floresca et al can claim benefits and at the same time sue. HELD: Under the law, Floresca et al could only do either one. If they filed for benefits under the WCA then they will be estopped from proceeding with a civil case before the regular courts. Conversely, if they sued before the civil courts then they would also be estopped from claiming benefits under the WCA. The SC however ruled that Floresca et al are excused from this deficiency due to ignorance of the fact. Had they been aware of such then they may have not availed of such a remedy. However, if in case theyll win in the lower court whatever award may be granted, the amount given to them under the WCA should be deducted. The SC emphasized that if they would go strictly by the book in this case then the purpose of the law may be defeated. Idolatrous reverence for the letter of the law sacrifices the human being. The spirit of the law insures mans survival and ennobles him As . Shakespeare said, the letter of the law killeth but its spirit giveth life. Justice Gutierrez dissenting No civil suit should prosper after claiming benefits under the WCA. If employers are already liable to pay benefits under theWCA they should not be compelled to bear the cost of damage suits or get insurance for that purpose. The exclusion provided by the WCA can only be properly removed by the legislature NOT the SC.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- LP 10 - Ylj - 301 - 7-6-10 - 0505Dokument6 SeitenLP 10 - Ylj - 301 - 7-6-10 - 0505roxie_mercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RR 06-2001 Full TextDokument7 SeitenRR 06-2001 Full Textroxie_mercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consti RevDokument20 SeitenConsti Revroxie_mercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PERSONS Marriage MatrixDokument6 SeitenPERSONS Marriage Matrixsaintkarri100% (1)

- StatCon ReportDokument2 SeitenStatCon Reportroxie_mercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macalintal V COMELECDokument1 SeiteMacalintal V COMELECroxie_mercado100% (1)

- PERSONS Marriage MatrixDokument6 SeitenPERSONS Marriage Matrixsaintkarri100% (1)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- FOR IC FILING OF UNITED COCONUT PLANTERS LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION FINANCIAL STATEMENTSDokument101 SeitenFOR IC FILING OF UNITED COCONUT PLANTERS LIFE ASSURANCE CORPORATION FINANCIAL STATEMENTSHoyo VerseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iles Greg - True EvilDokument317 SeitenIles Greg - True Evilpunto198367% (3)

- Pa SS1+2 HWDokument10 SeitenPa SS1+2 HWHà Anh ĐỗNoch keine Bewertungen

- Email Ids and Private Video Link UpdatedDokument4 SeitenEmail Ids and Private Video Link UpdatedPriyanshu BalaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Project Report On Derivatives (Futures & Options)Dokument98 SeitenA Project Report On Derivatives (Futures & Options)Sagar Paul'gNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ravine and Natural Feature Permit ApplicationDokument1 SeiteRavine and Natural Feature Permit ApplicationMichael TilbrookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of ExplanationDokument3 SeitenAffidavit of ExplanationDolores PulisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary WorldDokument39 SeitenContemporary WorldEmmanuel Bo100% (9)

- Learning Module: Andres Bonifacio CollegeDokument70 SeitenLearning Module: Andres Bonifacio CollegeAMANCIO DailynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Foreign Affairs March April 2021 Issue NowDokument236 SeitenForeign Affairs March April 2021 Issue NowShoaib Ahmed0% (1)

- MX - Inside The Uda Volunteers and ViolenceDokument242 SeitenMX - Inside The Uda Volunteers and ViolencePedro Navarro SeguraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mac16Cm, Mac16Cn Triacs: Silicon Bidirectional ThyristorsDokument6 SeitenMac16Cm, Mac16Cn Triacs: Silicon Bidirectional Thyristorsmauricio zamoraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume (Purcom)Dokument2 SeitenResume (Purcom)Angelo GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cerilles v. CSCDokument2 SeitenCerilles v. CSCMina AragonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accuride Wheel End Solution BrakeDokument56 SeitenAccuride Wheel End Solution Brakehebert perezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Public Private Partnership Model For Affordable Housing Provision in NigeriaDokument14 SeitenPublic Private Partnership Model For Affordable Housing Provision in Nigeriawidya nugrahaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 193 of 2013 2015 SCMR 456 Ali Azhar Khan Baloch VS Province of SindhDokument75 Seiten193 of 2013 2015 SCMR 456 Ali Azhar Khan Baloch VS Province of SindhAbdul Hafeez100% (1)

- Authorization LetterDokument3 SeitenAuthorization LetterAnik Roy.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ross Video Switcher Carbonite Operation ManualDokument62 SeitenRoss Video Switcher Carbonite Operation ManualClaudio C. SterleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Accounting A Managerial Perspective PDFDokument3 SeitenFinancial Accounting A Managerial Perspective PDFVijay Phani Kumar10% (10)

- Physics For Scientists and Engineers 9th Edition Serway Test BankDokument30 SeitenPhysics For Scientists and Engineers 9th Edition Serway Test Banktopical.alemannic.o8onrh100% (30)

- Order 3520227869817Dokument3 SeitenOrder 3520227869817Malik Imran Khaliq AwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS Amonium OksalatDokument5 SeitenMSDS Amonium OksalatAdi Kurniawan EffendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- RHB Auto Finance Customer Service Request FormDokument1 SeiteRHB Auto Finance Customer Service Request FormParang Tumpul100% (2)

- CG and Other StakeholdersDokument13 SeitenCG and Other StakeholdersFrandy KarundengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship Reviewer FinalsDokument7 SeitenEntrepreneurship Reviewer FinalsEricka Joy HermanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Egypt flight reservation under processDokument2 SeitenBook Egypt flight reservation under processmaged wagehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ppa LetterDokument1 SeitePpa LetterBabangida GarbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rental Venue 2018 - Glass HouseDokument2 SeitenRental Venue 2018 - Glass HouseoktreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Barnes LawsuitDokument20 SeitenBarnes LawsuitNewsTeam20Noch keine Bewertungen