Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Rule 63 Cases

Hochgeladen von

Vin BautistaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rule 63 Cases

Hochgeladen von

Vin BautistaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Rule 63.

Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

EN BANC G.R. No. 94723 August 21, 1997 KAREN E. SALVACION, minor, thru Federico N. Salvacion, Jr., father and Natural Guardian, and Spouses FEDERICO N. SALVACION, JR., and EVELINA E. SALVACION, petitioners, vs. CENTRAL BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES, CHINA BANKING CORPORATION and GREG BARTELLI y NORTHCOTT, respondents.

TORRES, JR., J.: In our predisposition to discover the "original intent" of a statute, courts become the unfeeling pillars of the status quo. Ligle do we realize that statutes or even constitutions are bundles of compromises thrown our way by their framers. Unless we exercise vigilance, the statute may already be out of tune and irrelevant to our day. The petition is for declaratory relief. It prays for the following reliefs: a.) Immediately upon the filing of this petition, an Order be issued restraining the respondents from applying and enforcing Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960; b.) After hearing, judgment be rendered: 1.) Declaring the respective rights and duties of petitioners and respondents; 2.) Adjudging Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 as contrary to the provisions of the Constitution, hence void; because its provision that "Foreign currency deposits shall be exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever i.) has taken away the right of petitioners to have the bank deposit of defendant Greg Bartelli y Northcott garnished to satisfy the judgment rendered in petitioners' favor in violation of substantive due process guaranteed by the Constitution; ii.) has given foreign currency depositors an undue favor or a class privilege in violation of the equal protection clause of the Constitution; iii.) has provided a safe haven for criminals like the herein respondent Greg Bartelli y Northcott since criminals could escape civil liability for their wrongful acts by merely converting their money to a foreign currency and depositing it in a foreign currency deposit account with an authorized bank. The antecedent facts: On February 4, 1989, Greg Bartelli y Northcott, an American tourist, coaxed and lured petitioner Karen Salvacion, then 12 years old to go with him to his apartment. Therein, Greg Bartelli detained Karen Salvacion for four days, or up to February 7, 1989 and was able to rape the child once on February 4, and three times each day on February 5, 6, and 7, 1989. On February 7, 1989, after policemen and people living nearby, rescued Karen, Greg Bartelli was arrested and detained at the Makati Municipal Jail. The policemen recovered from Bartelli the following items: 1.) Dollar Check No. 368, Control No. 021000678-1166111303, US 3,903.20; 2.) COCOBANK Bank Book No. 104-108758-8 (Peso Acct.); 3.) Dollar Account China Banking Corp., US$/A# 54105028-2 ; 4.) ID-122-30-8877; 5.) Philippine Money (P234.00) cash; 6.) Door Keys 6 pieces; 7.) Stuffed Doll (Teddy Bear) used in seducing the complainant. On February 16, 1989, Makati Investigating Fiscal Edwin G. Condaya filed against Greg Bartelli, Criminal Case No. 801 for Serious Illegal Detention and Criminal Cases Nos. 802, 803, 804, and 805 for four (4) counts of Rape. On the same day, petitioners filed with the Regional Trial Court of Makati Civil Case No. 89-3214 for damages with preliminary attachment against Greg Bartelli. On February 24, 1989, the day there was a scheduled hearing for Bartelli's petition for bail the latter escaped from jail.

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

On February 28, 1989, the court granted the fiscal's Urgent Ex-Parte Motion for the Issuance of Warrant of Arrest and Hold Departure Order. Pending the arrest of the accused Greg Bartelli y Northcott, the criminal cases were archived in an Order dated February 28, 1989. Meanwhile, in Civil Case No. 89-3214, the Judge issued an Order dated February 22, 1989 granting the application of herein petitioners, for the issuance of the writ of preliminary attachment. After petitioners gave Bond No. JCL (4) 1981 by FGU Insurance Corporation in the amount of P100,000.00, a Writ of Preliminary Attachment was issued by the trial court on February 28, 1989. On March 1, 1989, the Deputy Sheriff of Makati served a Notice of Garnishment on China Banking Corporation. In a letter dated March 13, 1989 to the Deputy Sheriff of Makati, China Banking Corporation invoked Republic Act No. 1405 as its answer to the notice of garnishment served on it. On March 15, 1989, Deputy Sheriff of Makati Armando de Guzman sent his reply to China Banking Corporation saying that the garnishment did not violate the secrecy of bank deposits since the disclosure is merely incidental to a garnishment properly and legally made by virtue of a court order which has placed the subject deposits in custodia legis. In answer to this letter of the Deputy Sheriff of Makati, China Banking Corporation, in a letter dated March 20, 1989, invoked Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 to the effect that the dollar deposits or defendant Greg Bartelli are exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body, whatsoever. This prompted the counsel for petitioners to make an inquiry with the Central Bank in a letter dated April 25, 1989 on whether Section 113 of CB Circular No. 960 has any exception or whether said section has been repealed or amended since said section has rendered nugatory the substantive right of the plaintiff to have the claim sought to be enforced by the civil action secured by way of the writ of preliminary attachment as granted to the plaintiff under Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court. The Central Bank responded as follows: May 26, 1989 Ms. Erlinda S. Carolino 12 Pres. Osmena Avenue South Admiral Village Paranaque, Metro Manila Dear Ms. Carolino: This is in reply to your letter dated April 25, 1989 regarding your inquiry on Section 113, CB Circular No. 960 (1983). The cited provision is absolute in application. It does not admit of any exception, nor has the same been repealed nor amended. The purpose of the law is to encourage dollar accounts within the country's banking system which would help in the development of the economy. There is no intention to render futile the basic rights of a person as was suggested in your subject letter. The law may be harsh as some perceive it, but it is still the law. Compliance is, therefore, enjoined. Very truly yours, (SGD) AGAPITO S. FAJARDO Director 1 Meanwhile, on April 10, 1989, the trial court granted petitioners' motion for leave to serve summons by publication in the Civil Case No. 89-3214 entitled "Karen Salvacion, et al. vs. Greg Bartelli y Northcott." Summons with the complaint was a published in the Manila Times once a week for three consecutive weeks. Greg Bartelli failed to file his answer to the complaint and was declared in default on August 7, 1989. After hearing the case ex-parte, the court rendered judgment in favor of petitioners on March 29, 1990, the dispositive portion of which reads: WHEREFORE, judgment is hereby rendered in favor of plaintiffs and against defendant, ordering the latter: 1. To pay plaintiff Karen E. Salvacion the amount of P500,000.00 as moral damages; 2. To pay her parents, plaintiffs spouses Federico N. Salvacion, Jr., and Evelina E. Salvacion the amount of P150,000.00 each or a total of P300,000.00 for both of them;

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

3. To pay plaintiffs exemplary damages of P100,000.00; and 4. To pay attorney's fees in an amount equivalent to 25% of the total amount of damages herein awarded; 5. To pay litigation expenses of P10,000.00; plus 6. Costs of the suit. SO ORDERED. The heinous acts of respondent Greg Bartelli which gave rise to the award were related in graphic detail by the trial court in its decision as follows: The defendant in this case was originally detained in the municipal jail of Makati but was able to escape therefrom on February 24, 1989 as per report of the Jail Warden of Makati to the Presiding Judge, Honorable Manuel M. Cosico of the Regional Trial Court of Makati, Branch 136, where he was charged with four counts of Rape and Serious Illegal Detention (Crim. Cases Nos. 802 to 805). Accordingly, upon motion of plaintiffs, through counsel, summons was served upon defendant by publication in the Manila Times, a newspaper of general circulation as attested by the Advertising Manager of the Metro Media Times, Inc., the publisher of the said newspaper. Defendant, however, failed to file his answer to the complaint despite the lapse of the period of sixty (60) days from the last publication; hence, upon motion of the plaintiffs, through counsel, defendant was declared in default and plaintiffs were authorized to present their evidence ex parte. In support of the complaint, plaintiffs presented as witnesses the minor Karen E. Salvacion, her father, Federico N. Salvacion, Jr., a certain Joseph Aguilar and a certain Liberato Madulio, who gave the following testimony: Karen took her first year high school in St. Mary's Academy in Pasay City but has recently transferred to Arellano University for her second year. In the afternoon of February 4, 1989, Karen was at the Plaza Fair Makati Cinema Square, with her friend Edna Tangile whiling away her free time. At about 3:30 p.m. while she was finishing her snack on a concrete bench in front of Plaza Fair, an American approached her. She was then alone because Edna Tangile had already left, and she was about to go home. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, pp. 2 to 5) The American asked her name and introduced himself as Greg Bartelli. He sat beside her when he talked to her. He said he was a Math teacher and told her that he has a sister who is a nurse in New York. His sister allegedly has a daughter who is about Karen's age and who was with him in his house along Kalayaan Avenue. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, pp. 4-5) The American asked Karen what was her favorite subject and she told him it's Pilipino. He then invited her to go with him to his house where she could teach Pilipino to his niece. He even gave her a stuffed toy to persuade her to teach his niece. (Id., pp. 5-6) They walked from Plaza Fair along Pasong Tamo, turning right to reach the defendant's house along Kalayaan Avenue. (Id., p. 6) When they reached the apartment house, Karen noticed that defendant's alleged niece was not outside the house but defendant told her maybe his niece was inside. When Karen did not see the alleged niece inside the house, defendant told her maybe his niece was upstairs, and invited Karen to go upstairs. (Id., p. 7) Upon entering the bedroom defendant suddenly locked the door. Karen became nervous because his niece was not there. Defendant got a piece of cotton cord and tied Karen's hands with it, and then he undressed her. Karen cried for help but defendant strangled her. He took a packing tape and he covered her mouth with it and he circled it around her head. (Id., p. 7) Then, defendant suddenly pushed Karen towards the bed which was just near the door. He tied her feet and hands spread apart to the bed posts. He knelt in front of her and inserted his finger in her sex organ. She felt severe pain. She tried to shout but no sound could come out because there were tapes on her mouth. When defendant withdrew his finger it was full of blood and Karen felt more pain after the withdrawal of the finger. (Id., p. 8)

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

He then got a Johnson's Baby Oil and he applied it to his sex organ as well as to her sex organ. After that he forced his sex organ into her but he was not able to do so. While he was doing it, Karen found it difficult to breathe and she perspired a lot while feeling severe pain. She merely presumed that he was able to insert his sex organ a little, because she could not see. Karen could not recall how long the defendant was in that position. (Id. pp. 8-9) After that, he stood up and went to the bathroom to wash. He also told Karen to take a shower and he untied her hands. Karen could only hear the sound of the water while the defendant, she presumed, was in the bathroom washing his sex organ. When she took a shower more blood came out from her. In the meantime, defendant changed the mattress because it was full of blood. After the shower, Karen was allowed by defendant to sleep. She fell asleep because she got tired crying. The incident happened at about 4:00 p.m. Karen had no way of determining the exact time because defendant removed her watch. Defendant did not care to give her food before she went to sleep. Karen woke up at about 8:00 o'clock the following morning. (Id., pp. 9-10) The following day, February 5, 1989, a Sunday, after a breakfast of biscuit and coke at about 8:30 to 9:00 a.m. defendant raped Karen while she was still bleeding. For lunch, they also took biscuit and coke. She was raped for the second time at about 12:00 to 2:00 p.m. In the evening, they had rice for dinner which defendant had stored downstairs; it was he who cooked the rice that is why it looks like "lugaw". For the third time, Karen was raped again during the night. During those three times defendant succeeded in inserting his sex organ but she could not say whether the organ was inserted wholly. Karen did not see any firearm or any bladed weapon. The defendant did not tie her hands and feet nor put a tape on her mouth anymore but she did not cry for help for fear that she might be killed; besides, all the windows and doors were closed. And even if she shouted for help, nobody would hear her. She was so afraid that if somebody would hear her and would be able to call the police, it was still possible that as she was still inside the house, defendant might kill her. Besides, the defendant did not leave that Sunday, ruling out her chance to call for help. At nighttime he slept with her again. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, pp. 12-14) On February 6, 1989, Monday, Karen was raped three times, once in the morning for thirty minutes after a breakfast of biscuits; again in the afternoon; and again in the evening. At first, Karen did not know that there was a window because everything was covered by a carpet, until defendant opened the window for around fifteen minutes or less to let some air in, and she found that the window was covered by styrofoam and plywood. After that, he again closed the window with a hammer and he put the styrofoam, plywood, and carpet back. (Id., pp. 14-15) That Monday evening, Karen had a chance to call for help, although defendant left but kept the door closed. She went to the bathroom and saw a small window covered by styrofoam and she also spotted a small hole. She stepped on the bowl and she cried for help through the hole. She cried: "Maawa no po kayo so akin. Tulungan n'yo akong makalabas dito. Kinidnap ako!" Somebody heard her. It was a woman, probably a neighbor, but she got angry and said she was "istorbo". Karen pleaded for help and the woman told her to sleep and she will call the police. She finally fell asleep but no policeman came. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, pp. 15-16) She woke up at 6:00 o'clock the following morning, and she saw defendant in bed, this time sleeping. She waited for him to wake up. When he woke up, he again got some food but he always kept the door locked. As usual, she was merely fed with biscuit and coke. On that day, February 7, 1989, she was again raped three times. The first at about 6:30 to 7:00 a.m., the second at about 8:30 9:00, and the third was after lunch at 12:00 noon. After he had raped her for the second time he left but only for a short while. Upon his return, he caught her shouting for help but he did not understand what she was shouting about. After she was raped the third time, he left the house. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, pp. 16-17) She again went to the bathroom and shouted for help. After shouting for about five minutes, she heard many voices. The voices were asking for her name and she gave her name as Karen Salvacion. After a while, she heard a voice of a woman saying they will just call the police. They were also telling her to change her clothes. She went from the bathroom to the room but she did not change her clothes being afraid that should the neighbors call for the police and the defendant see her in different clothes, he might kill her. At that time she was wearing a Tshirt of the American because the latter washed her dress. (Id., p. 16) Afterwards, defendant arrived and he opened the door. He asked her if she had asked for help because there were many policemen outside and she denied it. He told her to change her clothes, and she did change to the one she was wearing on Saturday. He instructed her to tell the police that she left home and willingly; then he went downstairs but he locked the door. She could hear people conversing but she could not understand what they were saying. (Id., p. 19) When she heard the voices of many people who were conversing downstairs, she knocked repeatedly at the door as hard as she could. She heard somebody going upstairs and when the door was opened, she saw a policeman. The

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

policeman asked her name and the reason why she was there. She told him she was kidnapped. Downstairs, he saw about five policemen in uniform and the defendant was talking to them. "Nakikipag-areglo po sa mga pulis," Karen added. "The policeman told him to just explain at the precinct. (Id., p. 20) They went out of the house and she saw some of her neighbors in front of the house. They rode the car of a certain person she called Kuya Boy together with defendant, the policeman, and two of her neighbors whom she called Kuya Bong Lacson and one Ate Nita. They were brought to Sub-Station I and there she was investigated by a policeman. At about 2:00 a.m., her father arrived, followed by her mother together with some of their neighbors. Then they were brought to the second floor of the police headquarters. (Id., p. 21) At the headquarters, she was asked several questions by the investigator. The written statement she gave to the police was marked as Exhibit A. Then they proceeded to the National Bureau of Investigation together with the investigator and her parents. At the NBI, a doctor, a medico-legal officer, examined her private parts. It was already 3:00 in the early morning of the following day when they reached the NBI. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, p. 22) The findings of the medico-legal officer has been marked as Exhibit B. She was studying at the St. Mary's Academy in Pasay City at the time of the incident but she subsequently transferred to Apolinario Mabini, Arellano University, situated along Taft Avenue, because she was ashamed to be the subject of conversation in the school. She first applied for transfer to Jose Abad Santos, Arellano University along Taft Avenue near the Light Rail Transit Station but she was denied admission after she told the school the true reason for her transfer. The reason for their denial was that they might be implicated in the case. (TSN, Aug. 15, 1989, p. 46) xxx xxx xxx After the incident, Karen has changed a lot. She does not play with her brother and sister anymore, and she is always in a state of shock; she has been absent-minded and is ashamed even to go out of the house. (TSN, Sept. 12, 1989, p. 10) She appears to be restless or sad, (Id., p. 11) The father prays for P500,000.00 moral damages for Karen for this shocking experience which probably, she would always recall until she reaches old age, and he is not sure if she could ever recover from this experience. (TSN, Sept. 24, 1989, pp. 10-11) Pursuant to an Order granting leave to publish notice of decision, said notice was published in the Manila Bulletin once a week for three consecutive weeks. After the lapse of fifteen (15) days from the date of the last publication of the notice of judgment and the decision of the trial court had become final, petitioners tried to execute on Bartelli's dollar deposit with China Banking Corporation. Likewise, the bank invoked Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960. Thus, petitioners decided to seek relief from this Court. The issues raised and the arguments articulated by the parties boil down to two: May this Court entertain the instant petition despite the fact that original jurisdiction in petitions for declaratory relief rests with the lower court? Should Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 and Section 8 of R.A. 6426, as amended by P.D. 1246, otherwise known as the Foreign Currency Deposit Act be made applicable to a foreign transient? Petitioners aver as heretofore stated that Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 providing that "Foreign currency deposits shall be exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever." should be adjudged as unconstitutional on the grounds that: 1.) it has taken away the right of petitioners to have the bank deposit of defendant Greg Bartelli y Northcott garnished to satisfy the judgment rendered in petitioners' favor in violation of substantive due process guaranteed by the Constitution; 2.) it has given foreign currency depositors an undue favor or a class privilege in violation of the equal protection clause of the Constitution; 3.) it has provided a safe haven for criminals like the herein respondent Greg Bartelli y Northcott since criminals could escape civil liability for their wrongful acts by merely converting their money to a foreign currency and depositing it in a foreign currency deposit account with an authorized bank; and 4.) The Monetary Board, in issuing Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 has exceeded its delegated quasi-legislative power when it took away: a.) the plaintiffs substantive right to have the claim sought to be enforced by the civil action secured by way of the writ of preliminary attachment as granted by Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court; b.) the plaintiffs substantive right to have the judgment credit satisfied by way of the writ of execution out of the bank deposit of the judgment debtor as granted to the judgment creditor by Rule 39 of the Revised Rules of Court, which is beyond its power to do so. On the other hand, respondent Central Bank, in its Comment alleges that the Monetary Board in issuing Section 113 of CB Circular No. 960 did not exceed its power or authority because the subject Section is copied verbatim from a portion of R.A. No. 6426 as amended

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

by P.D. 1246. Hence, it was not the Monetary Board that grants exemption from attachment or garnishment to foreign currency deposits, but the law (R.A. 6426 as amended) itself; that it does not violate the substantive due process guaranteed by the Constitution because a.) it was based on a law; b.) the law seems to be reasonable; c.) it is enforced according to regular methods of procedure; and d.) it applies to all members of a class. Expanding, the Central Bank said; that one reason for exempting the foreign currency deposits from attachment, garnishment or any other order or process of any court, is to assure the development and speedy growth of the Foreign Currency Deposit System and the Offshore Banking System in the Philippines; that another reason is to encourage the inflow of foreign currency deposits into the banking institutions thereby placing such institutions more in a position to properly channel the same to loans and investments in the Philippines, thus directly contributing to the economic development of the country; that the subject section is being enforced according to the regular methods of procedure; and that it applies to all foreign currency deposits made by any person and therefore does not violate the equal protection clause of the Constitution. Respondent Central Bank further avers that the questioned provision is needed to promote the public interest and the general welfare; that the State cannot just stand idly by while a considerable segment of the society suffers from economic distress; that the State had to take some measures to encourage economic development; and that in so doing persons and property may be subjected to some kinds of restraints or burdens to secure the general welfare or public interest. Respondent Central Bank also alleges that Rule 39 and Rule 57 of the Revised Rules of Court provide that some properties are exempted from execution/attachment especially provided by law and R.A. No. 6426 as amended is such a law, in that it specifically provides, among others, that foreign currency deposits shall be exempted from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever. For its part, respondent China Banking Corporation, aside from giving reasons similar to that of respondent Central Bank, also stated that respondent China Bank is not unmindful of the inhuman sufferings experienced by the minor Karen E. Salvacion from the beastly hands of Greg Bartelli; that it is only too willing to release the dollar deposit of Bartelli which may perhaps partly mitigate the sufferings petitioner has undergone; but it is restrained from doing so in view of R.A. No. 6426 and Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960; and that despite the harsh effect of these laws on petitioners, CBC has no other alternative but to follow the same. This Court finds the petition to be partly meritorious. Petitioner deserves to receive the damages awarded to her by the court. But this petition for declaratory relief can only be entertained and treated as a petition for mandamus to require respondents to honor and comply with the writ of execution in Civil Case No. 893214. This Court has no original and exclusive jurisdiction over a petition for declaratory relief. 2 However, exceptions to this rule have been recognized. Thus, where the petition has far-reaching implications and raises questions that should be resolved, it may be treated as one for mandamus. 3 Here is a child, a 12-year old girl, who in her belief that all Americans are good and in her gesture of kindness by teaching his alleged niece the Filipino language as requested by the American, trustingly went with said stranger to his apartment, and there she was raped by said American tourist Greg Bartelli. Not once, but ten times. She was detained therein for four (4) days. This American tourist was able to escape from the jail and avoid punishment. On the other hand, the child, having received a favorable judgment in the Civil Case for damages in the amount of more than P1,000,000.00, which amount could alleviate the humiliation, anxiety, and besmirched reputation she had suffered and may continue to suffer for a long, long time; and knowing that this person who had wronged her has the money, could not, however get the award of damages because of this unreasonable law. This questioned law, therefore makes futile the favorable judgment and award of damages that she and her parents fully deserve. As stated by the trial court in its decision, Indeed, after hearing the testimony of Karen, the Court believes that it was undoubtedly a shocking and traumatic experience she had undergone which could haunt her mind for a long, long time, the mere recall of which could make her feel so humiliated, as in fact she had been actually humiliated once when she was refused admission at the Abad Santos High School, Arellano University, where she sought to transfer from another school, simply because the school authorities of the said High School learned about what happened to her and allegedly feared that they might be implicated in the case. xxx xxx xxx The reason for imposing exemplary or corrective damages is due to the wanton and bestial manner defendant had committed the acts of rape during a period of serious illegal detention of his hapless victim, the minor Karen Salvacion whose only fault was in her being so naive and credulous to believe easily that defendant, an American national, could not have such a bestial desire on her nor capable of committing such a heinous crime. Being only 12

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

years old when that unfortunate incident happened, she has never heard of an old Filipino adage that in every forest there is a snake, . . . . 4 If Karen's sad fate had happened to anybody's own kin, it would be difficult for him to fathom how the incentive for foreign currency deposit could be more important than his child's rights to said award of damages; in this case, the victim's claim for damages from this alien who had the gall to wrong a child of tender years of a country where he is a mere visitor. This further illustrates the flaw in the questioned provisions. It is worth mentioning that R.A. No. 6426 was enacted in 1983 or at a time when the country's economy was in a shambles; when foreign investments were minimal and presumably, this was the reason why said statute was enacted. But the realities of the present times show that the country has recovered economically; and even if not, the questioned law still denies those entitled to due process of law for being unreasonable and oppressive. The intention of the questioned law may be good when enacted. The law failed to anticipate the iniquitous effects producing outright injustice and inequality such as the case before us. It has thus been said that But I also know, 5 that laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths are disclosed and manners and opinions change with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also, and keep pace with the times. . . We might as well require a man to wear still the coat which fitted him when a boy, as civilized society to remain ever under the regimen of their barbarous ancestors. In his Comment, the Solicitor General correctly opined, thus: The present petition has far-reaching implications on the right of a national to obtain redress for a wrong committed by an alien who takes refuge under a law and regulation promulgated for a purpose which does not contemplate the application thereof envisaged by the alien. More specifically, the petition raises the question whether the protection against attachment, garnishment or other court process accorded to foreign currency deposits by PD No. 1246 and CB Circular No. 960 applies when the deposit does not come from a lender or investor but from a mere transient or tourist who is not expected to maintain the deposit in the bank for long. The resolution of this question is important for the protection of nationals who are victimized in the forum by foreigners who are merely passing through. xxx xxx xxx . . . Respondents China Banking Corporation and Central Bank of the Philippines refused to honor the writ of execution issued in Civil Case No. 89-3214 on the strength of the following provision of Central Bank Circular No. 960: Sec. 113. Exemption from attachment. Foreign currency deposits shall be exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever. Central Bank Circular No. 960 was issued pursuant to Section 7 of Republic Act No. 6426: Sec. 7. Rules and Regulations. The Monetary Board of the Central Bank shall promulgate such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the provisions of this Act which shall take effect after the publication of such rules and regulations in the Official Gazette and in a newspaper of national circulation for at least once a week for three consecutive weeks. In case the Central Bank promulgates new rules and regulations decreasing the rights of depositors, the rules and regulations at the time the deposit was made shall govern. The aforecited Section 113 was copied from Section 8 of Republic Act NO. 6426, as amended by P.D. 1246, thus: Sec. 8. Secrecy of Foreign Currency Deposits. All foreign currency deposits authorized under this Act, as amended by Presidential Decree No. 1035, as well as foreign currency deposits authorized under Presidential Decree No. 1034, are hereby declared as and considered of an absolutely confidential nature and, except upon the written permission of the depositor, in no

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

instance shall such foreign currency deposits be examined, inquired or looked into by any person, government official, bureau or office whether judicial or administrative or legislative or any other entity whether public or private: Provided, however, that said foreign currency deposits shall be exempt from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever. The purpose of PD 1246 in according protection against attachment, garnishment and other court process to foreign currency deposits is stated in its whereases, viz.: WHEREAS, under Republic Act No. 6426, as amended by Presidential Decree No. 1035, certain Philippine banking institutions and branches of foreign banks are authorized to accept deposits in foreign currency; WHEREAS, under the provisions of Presidential Decree No. 1034 authorizing the establishment of an offshore banking system in the Philippines, offshore banking units are also authorized to receive foreign currency deposits in certain cases; WHEREAS, in order to assure the development and speedy growth of the Foreign Currency Deposit System and the Offshore Banking System in the Philippines, certain incentives were provided for under the two Systems such as confidentiality of deposits subject to certain exceptions and tax exemptions on the interest income of depositors who are nonresidents and are not engaged in trade or business in the Philippines; WHEREAS, making absolute the protective cloak of confidentiality over such foreign currency deposits, exempting such deposits from tax, and guaranteeing the vested rights of depositors would better encourage the inflow of foreign currency deposits into the banking institutions authorized to accept such deposits in the Philippines thereby placing such institutions more in a position to properly channel the same to loans and investments in the Philippines, thus directly contributing to the economic development of the country; Thus, one of the principal purposes of the protection accorded to foreign currency deposits is "to assure the development and speedy growth of the Foreign Currency Deposit system and the Offshore Banking in the Philippines" (3rd Whereas). The Offshore Banking System was established by PD No. 1034. In turn, the purposes of PD No. 1034 are as follows: WHEREAS, conditions conducive to the establishment of an offshore banking system, such as political stability, a growing economy and adequate communication facilities, among others, exist in the Philippines; WHEREAS, it is in the interest of developing countries to have as wide access as possible to the sources of capital funds for economic development; WHEREAS, an offshore banking system based in the Philippines will be advantageous and beneficial to the country by increasing our links with foreign lenders, facilitating the flow of desired investments into the Philippines, creating employment opportunities and expertise in international finance, and contributing to the national development effort. WHEREAS, the geographical location, physical and human resources, and other positive factors provide the Philippines with the clear potential to develop as another financial center in Asia; On the other hand, the Foreign Currency Deposit system was created by PD. No. 1035. Its purposes are as follows: WHEREAS, the establishment of an offshore banking system in the Philippines has been authorized under a separate decree; WHEREAS, a number of local commercial banks, as depository bank under the Foreign Currency Deposit Act (RA No. 6426), have the resources and managerial competence to more actively

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

engage in foreign exchange transactions and participate in the grant of foreign currency loans to resident corporations and firms; WHEREAS, it is timely to expand the foreign currency lending authority of the said depository banks under RA 6426 and apply to their transactions the same taxes as would be applicable to transaction of the proposed offshore banking units; It is evident from the above [Whereas clauses] that the Offshore Banking System and the Foreign Currency Deposit System were designed to draw deposits from foreign lenders and investors (Vide second Whereas of PD No. 1034; third Whereas of PD No. 1035). It is these deposits that are induced by the two laws and given protection and incentives by them. Obviously, the foreign currency deposit made by a transient or a tourist is not the kind of deposit encouraged by PD Nos. 1034 and 1035 and given incentives and protection by said laws because such depositor stays only for a few days in the country and, therefore, will maintain his deposit in the bank only for a short time. Respondent Greg Bartelli, as stated, is just a tourist or a transient. He deposited his dollars with respondent China Banking Corporation only for safekeeping during his temporary stay in the Philippines. For the reasons stated above, the Solicitor General thus submits that the dollar deposit of respondent Greg Bartelli is not entitled to the protection of Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 and PD No. 1246 against attachment, garnishment or other court processes. 6 In fine, the application of the law depends on the extent of its justice. Eventually, if we rule that the questioned Section 113 of Central Bank Circular No. 960 which exempts from attachment, garnishment, or any other order or process of any court, legislative body, government agency or any administrative body whatsoever, is applicable to a foreign transient, injustice would result especially to a citizen aggrieved by a foreign guest like accused Greg Bartelli. This would negate Article 10 of the New Civil Code which provides that "in case of doubt in the interpretation or application of laws, it is presumed that the lawmaking body intended right and justice to prevail. "Ninguno non deue enriquecerse tortizeramente con dano de otro." Simply stated, when the statute is silent or ambiguous, this is one of those fundamental solutions that would respond to the vehement urge of conscience. (Padilla vs. Padilla, 74 Phil. 377). It would be unthinkable, that the questioned Section 113 of Central Bank No. 960 would be used as a device by accused Greg Bartelli for wrongdoing, and in so doing, acquitting the guilty at the expense of the innocent. Call it what it may but is there no conflict of legal policy here? Dollar against Peso? Upholding the final and executory judgment of the lower court against the Central Bank Circular protecting the foreign depositor? Shielding or protecting the dollar deposit of a transient alien depositor against injustice to a national and victim of a crime? This situation calls for fairness against legal tyranny. We definitely cannot have both ways and rest in the belief that we have served the ends of justice. IN VIEW WHEREOF, the provisions of Section 113 of CB Circular No. 960 and PD No. 1246, insofar as it amends Section 8 of R.A. No. 6426 are hereby held to be INAPPLICABLE to this case because of its peculiar circumstances. Respondents are hereby REQUIRED to COMPLY with the writ of execution issued in Civil Case No. 89-3214, "Karen Salvacion, et al. vs. Greg Bartelli y Northcott, by Branch CXLIV, RTC Makati and to RELEASE to petitioners the dollar deposit of respondent Greg Bartelli y Northcott in such amount as would satisfy the judgment. SO ORDERED. Narvasa, C.J., Regalado, Davide, Jr., Romero, Bellosillo, Melo, Puno, Vitug, Kapunan, Francisco and Panganiban, JJ., concur. Padilla, J., took no part. Mendoza and Hermosisima, Jr., JJ., are on leave.

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

10

THIRD DIVISION G.R. No. 134958 January 31, 2001

PATRICIO CUTARAN, DAVID DANGWAS and PACIO DOSIL, petitioners, vs. DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT and NATURAL RESOURCES, herein represented by SEC. VICTOR O. RAMOS, OSCAR M. HAMADA and GUILLERMO S. FIANZA, in his capacity as Chairman of Community Special Task Force on Ancestral Lands (CSTFAL), Baguio City, respondents. GONZAGA-REYES, J.: Before us is a petition for review of the decision rendered by the Court of Appeals on March 25, 1998 and the order dated August 5, 1998 in CA-G.R. SP No. 43930, a petition for prohibition originally filed with the appellate court to enjoin the respondent DENR from implementing DENR Special Order Nos. 31, as amended by 31-A and 31-B, series of 1990, Special Order No. 25, series of 1993 and all other administrative issuances relative thereto, for having been issued without prior legislative authority.

1wphi1.nt

In 1990 the Assistant Secretary for Luzon Operations of the DENR issued Special Order no. 31 1 entitled "Creation of a Special Task force on acceptance, identification, evaluation and delineation of ancestral land claims in the Cordillera Administrative Region". The special task force created thereunder was authorized to accept and evaluate and delineate ancestral and claims within the said area, and after due evaluation of the claims, to issue appropriate land titles (Certificate of Ancestral Land Claim) in accordance with existing laws.2 On January 15, 1993 the Secretary of the DENR issued Special Order no. 253 entitled "Creation of Special Task Forces provincial and community environment and natural resources offices for the identification, delineation and recognition of ancestral land claims nationwide" and Department Administrative Order no. 02,4 containing the Implementing Rules and Guidelines of Special Order no. 25. In 1990, the same year Special Order no. 31 was issued, the relatives of herein petitioners filed separate applications for certificate of ancestral land claim (CALC) over the land they, respectively occupy inside the Camp John Hay Reservation. In 1996 the applications were denied by the DENR Community Special Task Force on Ancestral Lands on the ground that the Bontoc and Applai tribes to which they belong are not among the recognized tribes of Baguio City. Also pursuant to the assailed administrative issuances the Heirs of Apeng Carantes filed an application5 for certification of ancestral land claim over a parcel of land also within Camp John Hay and overlapping some portions of the land occupied by the petitioners. Petitioners claim that even if no certificate of ancestral land claim has yet been issued by the DENR in favor of the heirs of Carantes, the latter, on the strength of certain documents issued by the DENR, tried to acquire possession of the land they applied for, including the portion occupied by herein petitioners. Petitioners also allege that the heirs of Carantes removed some of the improvements they introduced within the area they actually occupy and if not for the petitioner's timely resistance to such intrusions, the petitioners would have been totally evicted therefrom. Hence, this petition for prohibition originally filed with the Court of Appeals to enjoin the respondent DENR from implementing the assailed administrative issuances and from processing the application for certificate of ancestral land claim (CALC) filed by the heirs of Carantes on the ground that the said administrative issuances are void for lack of legal basis. The Court of Appeals6 held that the assailed DENR Special Orders Nos. 31, 31-A, 31-B issued in 1990 prior to the effectivity of RA 7586 known as the National Integrated Protected Areas Systems (NIPAS) Act of 1992, are of no force and effect "for pre-empting legislative prerogative" but sustained the validity of DENR Special Order No. 25, and its implementing rules (DAO No. 02, series of 1993) by the appellate court on the ground that they were issued pursuant to the powers delegated to the DENR under section 13 of RA 7586, which reads: "Section 13. Ancestral Lands and Rights over Them. Ancestral lands and customary rights and interest arising therefrom shall be accorded due recognition. The DENR shall prescribe rules and regulations to govern ancestral lands within protected areas: Provided, that the DENR shall have no power to evict indigenous communities from their present occupancy nor resettle them to another area without their consent: Provided, however, that all rules and regulations, whether adversely affecting said communities or not, shall be subjected to notice and hearing to be participated in by members of concerned indigenous community."7 The petitioners filed with this Court a petition for review of the appellate court's decision on the ground that the Court of Appeals erred in upholding the validity of Special Order No. 25 and its implementing rules. The petitioners seek to enjoin the respondent DENR from processing the application for certificate of ancestral land claim filed by the Heirs of Carantes. Petitioners contend that in addition to the failure of the DENR to publish the assailed administrative issuances in a newspaper of general circulation prior to its implementation, RA 7586, which provides for the creation of a National Integrated Protected Areas System, does not contain the slightest implication of

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

11

a grant of authority to the DENR to adjudicate or confer title over lands occupied by indigenous communities. It is contended that the said law only grants DENR administrative and managerial powers over designated national and natural parks called "protected areas" wherein rare and endangered species of plants and animals inhabit.8 The petitioners further allege that the subsequent passage of in 1997 of Republic Act 8371, otherwise known as the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act, wherein the power to evaluate and issue certificates of ancestral land titles is vested in the National Commission on Indigenous Cultural Communities/Indigenous People (NCIP) is unmistakable indication of the legislature's withholding of authority from the DENR to confer title over lands occupied by indigenous communities.9 Finally, the petitioners claim that the validity of the questioned DENR special orders cannot be based on the constitutional provisions regarding the protection of cultural communities as the said provisions are policy statements to guide the legislature in the exercise of their law-making powers and by themselves are not self-executory. The Solicitor-General filed memorandum in behalf of the respondent DENR praying for the affirmance of the appellate court's decision. The respondent argues that the subject DENR special orders were issued pursuant to the powers granted by RA 7586 to the DENR to protect the socio-economic interests of indigenous peoples. The land occupied by the petitioners is within a "protected area" as defined by the said law and is well within the jurisdiction of the DENR. The respondent likewise claims that the petitioners are estopped from contesting the validity of the DENR administrative issuances considering that their relatives applied for certificates of ancestral land claim (CALC) under the said special orders which applications were, however, denied. The petitioners should not be allowed to challenge the same administrative orders which they themselves previously invoked. The respondents do not contest the ruling of the appellate court as regards the nullity of Special Order no. 31, as amended. The sole issue before us concerns the validity of DENR Special Order no. 25, series of 1993 and its implementing rules DAO no. 02. The petitioners' main contention is that the assailed administrative orders were issued beyond the jurisdiction or power of the DENR secretary under the NIPAS Act of 1992. They seek to enjoin the respondents from processing the application for ancestral land claim filed by the heirs of Carantes because if approved, the petitioners may be evicted from the portion of the land they occupy which overlaps the land applied for by the Carantes heirs. From a reading of the records it appears to us that the petition was prematurely filed. Under the undisputed facts there is as yet no justiciable controversy for the court to resolve and the petition should have been dismissed by the appellate court on this ground. We gather from the allegations of the petition and that of the petitioners' memorandum that the alleged application for certificate of ancestral land claim (CALC) filed by the heirs of Carantes under the assailed DENR special orders has not been granted nor the CALC applied for, issued. The DENR is still processing the application of the heirs of Carantes for a certificate of ancestral land claim, which the DENR may or may not grant. It is evident that the adverse legal interests involved in this case are the competing claims of the petitioners and that of the heirs of Carantes to possess a common portion of a piece of land. As the undisputed facts stand there is no justiciable controversy between the petitioners and the respondents as there is no actual or imminent violation of the petitioners' asserted right to possess the land by reason by the implementation of the questioned administrative issuances. A justiciable controversy has been defined as, "a definite and concrete dispute touching on the legal relations of parties having adverse legal interest"10 which may be resolved by a court of law through the application of a law. 11 Courts have no judicial power to review cases involving political questions and as a rule, will desist from taking cognizance of speculative or hypothetical cases, advisory opinions and in cases that has become moot.12Subject to certain well-defined exceptions13 courts will not touch an issue involving the validity of a law unless there has been a governmental act accomplished or performed that has a direct adverse effect on the legal right of the person contesting its validity.14 In the case of PACU vs. Secretary of Education15 the petition contesting the validity of a regulation issued by the Secretary of Education requiring private schools to secure a permit to operate was dismissed on the ground that all the petitioners have permits and are actually operating under the same. The petitioners questioned the regulation because of the possibility that the permit might be denied them in the future. This Court held that there was no justiciable controversy because the petitioners suffered no wrong by the implementation of the questioned regulation and therefore, they are not entitled to relief. A mere apprehension that the Secretary of Education will withdraw the permit does not amount to a justiciable controversy. The questioned regulation in the PACU case may be questioned by a private school whose permit to operate has been revoked or one whose application therefor has been denied.16 This Court cannot rule on the basis of petitioners' speculation that the DENR will approve the application of the heirs of Carantes. There must be an actual governmental act which directly causes or will imminently cause injury to the alleged right of the petitioner to possess the land before the jurisdiction of this Court may be invoked. There is no showing that the petitioners were being evicted from the land by the heirs of Carantes under orders from the DENR. The petitioners' allegation that certain documents from the DENR were shown to them by the heirs of Carantes to justify eviction is vague, and it would appear that the petitioners did not verify if indeed the respondent DENR or its officers authorized the attempted eviction. Suffice it to say that by the petitioners own admission that the respondents are still processing and have not approved the application of the heirs of Carantes, the petitioners alleged right to possess the land is not violated nor is in imminent danger of being violated, as the DENR may or may not approve Carantes' application. Until such time, the petitioners are simply speculating that they might be evicted from the premises at some future time. Borrowing from the pronouncements of this Court in the PACU case, "They (the petitioners) have suffered no wrong under the terms of the lawand, naturally need no relief in the form they now seek to obtain."17 If indeed the heirs of Carantes are trying to enter the land and disturbing

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

12

the petitioners possession thereof even without prior approval by the DENR of the claim of the heirs of Carantes, the case is simply one for forcible entry. Wherefore, for lack of justiciable controversy, the decision of the appellate court is hereby set aside. SO ORDERED. Melo, Vitug, Panganiban, and Sandoval Gutierrez, JJ., concur.

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

13

EN BANC G.R. No. L-2402 November 29, 1950

SANTIAGO DEGALA, plaintiff-appellee, vs. CECILIA REYES and VALENTIN UMIPIG, defendants-appellants. J. Quintillan for appellants. Antonio Directo for appellee. FERIA, J.: During the pendency of the appeal from the order of the Court of First Instance of Ilocos Sur probating a will executed by the late Placida Mina of Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur on April 22, 1927, Santiago Degala, alleging that he is one of the legal heirs of said Placida Mina, filed a petition with the court praying that the provisions of said will and testament creating a trust be declared null and void because there is no cestui que named therein, under Rule 66 on Declaratory judgment. The said will provides, among others, the following: SEGUNDO. Las rentas o productos de mis terrenos, casas y animales con excepcion de las parcelas de terreno arriba mencionadas se aplicaran al pago de amillaramiento de mis propiedades, para la reparacion y continuacion de la construccion de mis dos casas de mamposteria que estan frente a frente, y para la realizacion de las misas dispuestas en este testamento; y caso de que sobrare algo se dispondra, en caso necesario, para ayudar en los gastos de la reparacion de la iglesia, convento y la antigua capilla del cementerio romano de Santa Maria y la iglesia de Burgos. xxx xxx xxx

OCTAVO. Ordeno que todos los aos empezando desde mi muerte se celebran misas cantadas en las fechas del dia de mi nacimiento y muerte, en sufragio de mi alma, de las de mis parientes mencionadas al comienzo de este testamento y de las de mis difuntos abuelos Santiago Mina y Florentina Degala, padre y madre de mi padre, y de las de Mariano Directo y Anastacia Peralta, padre y madre de mi madre. The only persons who were made party defendants in the petition for declaratory judgment are Cecilia Reyes, petitioner for the probate of the will in case No. 3689, Valentin Umipig, special administrator of the estate of the deceased appointed by the court, and Leona Leones and Cipriana Alcantara named as trustees under the will. After the hearing of the petition, the Court of First Instance of Ilocos Sur held that if it were not the unanimous desire of all the parties that the court declare, once and for all, whether certain provisions of the will are null and void or not, it would dismiss the petition for declaratory judgment in accordance with American precedents, because the judgment of the lower court probating the will was then still pending appeal in the Supreme Court. But in view of such unanimous desire, the court declared, among others, that the above quoted provisions of the will creating a fideicomiso or trust are null and void, because the testatrix has not named the first heir or cestui que trust and because they are contrary to the law on perpetuities. The defendants Cecilia Reyes and Valentin Umipig appealed from the said judgment to this court. The appellants in a well written brief contend (1) that the provisions in the will or testament of the late Placida Mina which leave certain properties of the testatrix for the saying of masses for the soul of the testatrix and her relatives and for the maintenance and repair of the church, convent and the old chapel of the Roman Catholic cemetery of Sta. Maria and of the church of Burgos, Ilocos Sur, create a charitable and religious trust; and this court in the case of Government of the Philippine Island vs. Abadilla (46 Phil., 642, 647), quoting Perry on Trusts, held that in regard to private trust it is not always necessary that the cestui que trust should be in esse at the time the trust is created in his favor, and that in charitable trust the rule is still further relaxed. And (2) as to prohibition to alienate the properties in trust, article 785 of the Civil Code provides that in fiduciary substitutions "dispositions, imposing perpetual prohibition and temporary prohibition beyond the limits fixed by article 781" are inoperative; and that article 792 prescribes that, impossible conditions and those contrary to law and good morals imposed in testamentary disposition shall be considered as not imposed, and shall not prejudice the heir or legatee in any manner whatsoever, even should the testator otherwise provide. It is obvious, that the Roman Catholic Church or its legal representative the Roman Catholic Bishop of Nueva Segovia, has interest in defending the validity of the trust created in the will and its interest would be affected by the declaration of nullity of the trust. Section 3,

Rule 63. Declaratory Relief & Similar Remedies

14

Rule 66, of the Rules of Court provides that "when declaratory relief is sought, all persons shall be made parties who have or claim any interest which would be affected by the declaration, and no declaration shall, except as otherwise provided in these rules, prejudice the rights of persons not parties to the action." The non-joinder of necessary parties would deprive the declaration of that final and pacifying function it is calculated to subserve, as they would not be bound by the declaration and may raise the identical issue (Hoskyns vs. National City Bank of New York, 85 Phil., 201.) "And the absence of a defendant with such adverse interest is a jurisdictional defect, and no declaratory judgment can be rendered" (Corpus Juris Secundum, Vol. I, p. 1049). But the Roman Catholic Church, or its legal representative was not included as party defendant in the present case. In view of the foregoing, the judgment appealed from in so far as it declares the trust under consideration null and void, is set aside, without pronouncement as to costs. So ordered. Moran, Bengzon, C. J., Paras, Pablo, Padilla, Tuason, Montemayor, Reyes, Jugo and Bautista, JJ., concur.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Judicial Ethics - Full Text Cases, Set 1Dokument129 SeitenJudicial Ethics - Full Text Cases, Set 1Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Judicial Ethics - Full Text Cases, Set 1Dokument129 SeitenJudicial Ethics - Full Text Cases, Set 1Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recommended Cases - Tax 2Dokument6 SeitenRecommended Cases - Tax 2Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Private International Law Cases Wills and PropertyDokument30 SeitenPrivate International Law Cases Wills and PropertyVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflicts Set 2Dokument20 SeitenConflicts Set 2Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Examination Questionnaire For TaxationDokument24 SeitenBar Examination Questionnaire For TaxationFrederick E. EurolfanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01 - Saudi Arabian Airlines Vs CA, GR 122191Dokument9 Seiten01 - Saudi Arabian Airlines Vs CA, GR 122191Joyce Hidalgo PreciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lee Yick Hon - CustomsDokument13 SeitenLee Yick Hon - CustomsVin Bautista100% (1)

- Special Proceedings FinalsDokument148 SeitenSpecial Proceedings FinalsVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- T He Case: vs. EDNA MALNGAN y MAYO, AppellantDokument18 SeitenT He Case: vs. EDNA MALNGAN y MAYO, AppellantVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spec Pro FinalsDokument121 SeitenSpec Pro FinalsVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (A.M. NO. 004-07-SC 2000-11-21) : Rule On Examination of A Child WitnessDokument13 Seiten(A.M. NO. 004-07-SC 2000-11-21) : Rule On Examination of A Child WitnessChrislyned Garces-TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. CagodDokument3 SeitenPeople v. CagodVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking Cases Set 2 (Complete)Dokument84 SeitenBanking Cases Set 2 (Complete)Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spec Pro MidtermsDokument15 SeitenSpec Pro MidtermsVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 69Dokument31 SeitenRule 69Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict of Laws Set 1Dokument29 SeitenConflict of Laws Set 1Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Banking Cases Set 1 (Almost Complete)Dokument149 SeitenBanking Cases Set 1 (Almost Complete)Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full Text Cases - Special Civil ActionsDokument58 SeitenFull Text Cases - Special Civil ActionsVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recommended Cases in Legal Forms Set 1Dokument33 SeitenRecommended Cases in Legal Forms Set 1Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revenue Regulations 02-03Dokument22 SeitenRevenue Regulations 02-03Anonymous HIBt2h6z7Noch keine Bewertungen

- Amended Small ClaimsDokument5 SeitenAmended Small ClaimscarterbrantNoch keine Bewertungen

- PalaganasDokument2 SeitenPalaganasVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 71Dokument28 SeitenRule 71Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SpecPro 120311 CasesDokument39 SeitenSpecPro 120311 CasesVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Title of The Code. Corporation Defined.: Sec. 1. Sec. 2Dokument27 SeitenTitle of The Code. Corporation Defined.: Sec. 1. Sec. 2Vin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence 112211 CasesDokument21 SeitenEvidence 112211 CasesVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine Ports AuthorityDokument16 SeitenPhilippine Ports AuthorityVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ra 8799Dokument45 SeitenRa 8799Colleen Rose GuanteroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rule 68 Foreclosure of Real Estate MortgageDokument10 SeitenRule 68 Foreclosure of Real Estate MortgageVin BautistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Sofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementDokument3 SeitenSofitel Montreal Hotel and Resorts AgreementJoyce ReisNoch keine Bewertungen

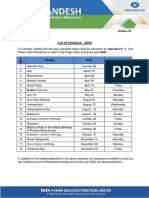

- Holiday List - 2020Dokument3 SeitenHoliday List - 2020nitin369Noch keine Bewertungen

- Error IdentificationDokument2 SeitenError IdentificationMildred TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ScribieDokument3 SeitenScribieNit's NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- G C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerDokument4 SeitenG C Am7 F Gsus G C F C: Chain BreakerChristine Torrepenida RasimoNoch keine Bewertungen

- WFRP Warhammer Dark ElvesDokument19 SeitenWFRP Warhammer Dark ElvesLance GoodthrustNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reason For Popularity of Charlie ChaplinDokument4 SeitenReason For Popularity of Charlie Chaplinmishra_ajay555Noch keine Bewertungen

- COMELEC resolution on 2001 special senate election upheldDokument2 SeitenCOMELEC resolution on 2001 special senate election upheldA M I R ANoch keine Bewertungen

- The Seventh Day Adventists - Sunday Study in CultsDokument30 SeitenThe Seventh Day Adventists - Sunday Study in CultssirjsslutNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 TimoteoDokument29 Seiten12 TimoteoPeter Paul RecaboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Succession ExplainedDokument211 SeitenSuccession ExplainedGoodFather100% (3)

- The Peace OfferingDokument8 SeitenThe Peace Offeringribka pittaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ApplicationDokument3 SeitenApplicationSusanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Curse of CanaanDokument2 SeitenThe Curse of CanaanNikita DatsichinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Saga v2 - Getting Started With Mutatawwi'aDokument4 SeitenSaga v2 - Getting Started With Mutatawwi'abaneblade1Noch keine Bewertungen

- CTM DWB400 Motor Safety and Installation InstructionsDokument1 SeiteCTM DWB400 Motor Safety and Installation Instructionsjeffv65Noch keine Bewertungen

- Citibank Vs TeodoroDokument7 SeitenCitibank Vs TeodoroCaroline DulayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Litany For The Faithful DepartedDokument2 SeitenLitany For The Faithful DepartedKiemer Terrence SechicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appl. Under Sec.10 CPC - For Stay of Suit 2021Dokument9 SeitenAppl. Under Sec.10 CPC - For Stay of Suit 2021divyasri bodapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPM TRIAL 2007 English Paper 2Dokument19 SeitenSPM TRIAL 2007 English Paper 2Raymond Cheang Chee-CheongNoch keine Bewertungen

- NocheDokument13 SeitenNocheKarlo NocheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Element of GenocideDokument18 SeitenElement of GenocidePrashantKumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managmnt DataDokument722 SeitenManagmnt DataAnurag Kanaujia100% (1)

- Words 2Dokument2.087 SeitenWords 2c695506urhen.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Villanueva vs. Court of AppealsDokument1 SeiteVillanueva vs. Court of AppealsPNP MayoyaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resolution To Censure Graham - PickensDokument12 SeitenResolution To Censure Graham - PickensJoshua CookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effect of An Arbitration AgreementDokument28 SeitenEffect of An Arbitration AgreementUpendra UpadhyayulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thers Something About Mary ScriptDokument142 SeitenThers Something About Mary ScriptsporangiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harsha Tipirneni Vs Pooja TipirneniDokument9 SeitenHarsha Tipirneni Vs Pooja TipirneniCSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Erotic Artworks Jonh o Dirty Anal Games PDFDokument2 SeitenErotic Artworks Jonh o Dirty Anal Games PDFLydiaNoch keine Bewertungen