Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Review of Fifty Key Figures in Islam by Roy Jackson

Hochgeladen von

mnasrin11Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review of Fifty Key Figures in Islam by Roy Jackson

Hochgeladen von

mnasrin11Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review of Fifty Key Figures in Islam by Roy Jackson, London: Routledge Key Guides (2006), pp.261+xvi.

This book claims to be the perfect resource for learning about muslim culture, people and its teachings. There are however some fundamental errors in regards to certain entries and also various terms are left unexplained. I was rather taken aback by the misinformation regarding alShafiI. According to the author al-ShafiI is credited to have laid the foundations for the science of jurisprudence in actual fact al-ShafiI is credited for his Risalah which is a textbook for the principles (usul al-fiqh) and not jurisprudence (fiqh) itself. Jackson does not distinguish between the two. Jackson also believed that this new foundation al-ShafiI had lain was independent of Aristotelian logic or dialectic. One has trouble understanding Jackson here as Aristotelian logic or dialectic entered principles of jurisprudence (usul al-Fiqh) after the time of al-ShafiI and not before him. Probably Jackson meant the principles of Qiyas or analogical reasoning which al-ShafiI had criticized. Nonetheless such confusion should not be within a book which claims to be a guide. Other mistakes abound, in the section on Ali, Jackson mistakenly alleged that the Quran used by the Shia Muslims today is the one compiled by Ali and is both longer (it has references to Ali) and different (pg.18) from that compiled by the third caliph Uthman. Such statements imply that the Shia Muslims have a different Quran from the majority of Muslims in the world. This view reflects a certain anti-shia propaganda affecting the author. Just a minor glance to any Iranian printed Quran today would reveal the reverse as it is similar to the ones being used by Muslims worldwide. There are also other few fundamental errors in history committed by Jackson especially in attributing Alis acceptance of arbitration due to him being old and tired (pg.20). A cursory glance at historical sources would indicate to us that Ali was forced to accept the arbitration at Siffin by a group of his supporters who were tricked by the tactics of putting the Quran on the tip of lances by Muawiya. This same group was later to become known as the seceders (al-khawarij). The excellent studies by Ayoub (Crises of Muslim History) and Madelung (Succession to Muhammad) should have supplemented this entry on Ali and Abu Bakr and other figures connected with the issue of succession. A correct understanding of this volatile period is crucial in understanding the main divisions between Sunni and ShiI sect within Islam. Unfortunately Jackson does not even refer to these sources focusing instead on other general history of the period for writing his entry. By alleging that the shiI have a different Quran than the Sunni community Jackson is actually playing into the hands of extremist groups which had always believed that and used it as a basis for attacks on the shiI community. One could not help but think the worse when reading the entry on ShiI and how this would help fuel such bigotry against the shiI community especially in such volatile areas such as Pakistan or even Iraq. Jackson had included 18 entries on contemporary muslim thinkers. One of them is Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab or al-Wahhab whom Jackson regards as one of the renewers of religion (pg.139) as indicated in the oft quoted hadith here. The renewers included with al-Wahhab are alGhazali, Ibn Taymiyyah and Shah Wali Allah. He is at pains to connect Shah Wali Allah as being similar to al-Wahhab and claims that their differences lie mainly in their approaches where alWahhab was militant if compared to the less confrontational approach of Wali Allah (pg.157). The entry on Wali Allah is interspersed with the opinions of al-Wahhab in Jacksons attempt to link the two scholar together. Surely the reality is that al-Wahhabs literary input or lack of it is incomparable to the impressive writings of Wali Allah (See Wahhabism by Hamid Algar). In the entry on al-Wahhab one cannot but ponder the orientations of Jackson as he alleges that the fall of the Ottoman empire was due to their hanging onto superstitious practices very much in line with the jihad or campaign of terror declared by the Bani Saud and the followers of al-Wahhab

(Wahhabis) against the Ottomans. There is no mention of the violence nor resistance towards the Saud and the Wahhabis from the local scholars nor the people of the then Hijjaz. Jackson skips all these and praises this great reviver as the person who has come to guide muslims when their Islamic activities were evidently shirk (pg.161). Many scholars have written about the violent rise of the Wahabbi movement (see Algar, Wahhabism for references in Arabic and others) and the various criticism leveled against them by prominent scholars of the period none however seems to have made it into Jacksons entry. One gets the impression that the Wahhabis were welcome and their founder a great scholar. The reality is that Muhammad ibn Abdul Wahhab was not a seminal figure in the history of muslim thought as whatever that he has written are mainly short and minimal responses towards certain questions and brief statements. Other mistakes and misunderstandings abound such as in the entry on Khomeini, Jackson grossly attributes the view that Mullahs or jurist are qualified to do ijtihad to Khomeini as if before Khomeini this was never within the whole corpus of shii legal writing and thought. One has trouble understanding Jackson here, what does he mean by the word jurist and mullah? As only qualified mujtahid are allowed to do ijtihad in the shiI legal tradition. Whatever he meant by the word it does demonstrate his ignorance of the facts involved in regards to the development of shiI legal thought. There are other mistakes in regards to the entry on Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini which includes him being regarded as the Mahdi by the ShiI (which has never been the case), he had clamped down on freedom of thought (pg.190) etc. Political views aside, such understanding on Khomeini and eventually the whole shiI legal tradition is surprising given the amount of studies written which is available in western language (see in particular works written by Modarressi Tabatabai). Overall the book attempts to cover all the major figures though the figures chosen are arbitrary. None of the other major Sufi writers (ibn Ataallah, Shadhili, Najm al-Din Kubra etc.) are included here apart from Ibn Arabi and Rumi. Due to the range of materials covered I would have wished that each entry be written by an expert scholar within the field. Thus as a guide it would have fulfilled its purpose as each entry would have been covered much more in depth and the suggested readings after each section would have been more enriched. However the end product as we have it here relies only upon the author whose inclinations sometimes influences the way he writes a certain entry as I have demonstrated above. Mohamad Nasrin Nasir University Brunei Darussalam

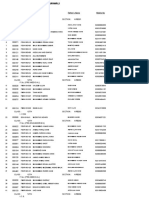

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Abuse of The People of Lut (English)Dokument54 SeitenAbuse of The People of Lut (English)Dar Haqq (Ahl'al-Sunnah Wa'l-Jama'ah)Noch keine Bewertungen

- First Term Jss2 Week 1 - 065249Dokument2 SeitenFirst Term Jss2 Week 1 - 065249Bello HassanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pembagian Kelompok+ Dosen Tutor IPE (Fix)Dokument58 SeitenPembagian Kelompok+ Dosen Tutor IPE (Fix)Ninda fadilahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islamic NamesDokument93 SeitenIslamic NamesMansoor Ahmed100% (3)

- New Born Baby Procedure PDFDokument17 SeitenNew Born Baby Procedure PDFShaik SarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- PROSIDING 2018 Conference Unhas ICAME PDFDokument61 SeitenPROSIDING 2018 Conference Unhas ICAME PDFirineNoch keine Bewertungen

- RampurDokument82 SeitenRampurrahatsenrsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural ExchangeDokument3 SeitenCultural ExchangeAqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cover Letter and ResumeDokument2 SeitenCover Letter and ResumeMiey JieyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Template Opening Ceremony Doa in EnglishDokument1 SeiteTemplate Opening Ceremony Doa in Englishrmhvnaz92% (13)

- Berne Convention For The Protection of Literary and Artistic WorksDokument5 SeitenBerne Convention For The Protection of Literary and Artistic WorksfeolacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- VND Ms-Excel&rendition 1Dokument4 SeitenVND Ms-Excel&rendition 1Muhammad AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Borang Transit PBD PJK Ting 3 2021Dokument6 SeitenBorang Transit PBD PJK Ting 3 2021hasliana mohd yunus100% (1)

- Revue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 11.Dokument334 SeitenRevue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 11.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urdu NaatDokument152 SeitenUrdu NaatSaadiyah mu100% (1)

- MySalahMat MiniBook01-DuaForSalahDokument6 SeitenMySalahMat MiniBook01-DuaForSalahhalemaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2019 5.3 FLY Project TopicsDokument5 Seiten2019 5.3 FLY Project TopicsShubham KalitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beema-E-Zindagi Life Insurance by Shaykh Mufti Muhammad ShafiDokument81 SeitenBeema-E-Zindagi Life Insurance by Shaykh Mufti Muhammad Shafisaif ur rehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salvadora PersicaDokument3 SeitenSalvadora PersicaVAXAEVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Car MavrikijeDokument2 SeitenCar MavrikijeVlada MarkovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mexican Halal StandardDokument86 SeitenMexican Halal StandardYaisa Marrugo JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- En Rights and Duties in Islam PDFDokument72 SeitenEn Rights and Duties in Islam PDFsirtariqNoch keine Bewertungen

- KEL Mentoring Ikhwan 2021 NewDokument8 SeitenKEL Mentoring Ikhwan 2021 NewZein FirmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Speech TextDokument6 SeitenEnglish Speech TextFika Atina Rizqiana100% (1)

- Chapter - 6 History Town, Traders and Craftspersons: Sources of Knowing About The History of This PeriodDokument2 SeitenChapter - 6 History Town, Traders and Craftspersons: Sources of Knowing About The History of This PeriodRohit RahulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selangor Times Sept 30 - Oct 2, 2011 / Issue 42Dokument24 SeitenSelangor Times Sept 30 - Oct 2, 2011 / Issue 42Selangor TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINALDokument116 SeitenFINALJerome Fayluga100% (1)

- Dilawer EssayDokument5 SeitenDilawer EssayDilawar Khoso0% (1)

- Satan's Counterfeit Israel, Antichrist & World RuleDokument26 SeitenSatan's Counterfeit Israel, Antichrist & World Rulelucscurtu100% (1)