Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Middle East Crisis and Its Impact On The Indian Economy

Hochgeladen von

Pranay JainOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Middle East Crisis and Its Impact On The Indian Economy

Hochgeladen von

Pranay JainCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

THE MIDDLE EAST CRISIS AND ITS IMPACT ON THE INDIAN ECONOMY

Background: What is Happening and Why? Between late 2010 and early 2011 a wave of spontaneous revolts in Tunisia and Egypt led to the downfall of the local regimes. Foreign exporters and investors in these countries are still being affected by the ongoing events, including looting, industrial action, supply chain disruptions and increased counterparty risk. Moreover, the success of the initial protests sparked new tensions across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), threatening the stability of Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Jordan, Libya and Yemen. Uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt The catalyst for these revolts was the suicide of young street vendor, Mohamed Bouazizi, in the Tunisian town of Sidi Bouzid in December 2010; Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest against a decision by the local authorities to seize his wares. In a few weeks demonstrations spread to the whole country, as many Tunisians took to the streets to protest against political repression and deteriorating living conditions. The combination of high youth unemployment, worsening living conditions, rising food prices, accusations of corruption and crony capitalism against President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali and his family, and the lack of legal outlets for widespread political discontent, led to an unprecedented uprising that the government was unable to stop. The aims of the revolt were to topple Ben Ali and replace his authoritarian regime with a multi-party democracy. The sudden collapse of Ben Alis regime opened a political vacuum. Parliament speaker Fouad Mebazaa replaced Ben Ali as president and a transition government, led by Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi, but including members of the opposition was formed. In February parliament granted emergency powers to the government, which can now rule by decree; this measure should enable the authorities to tackle the challenges posed by the difficult political transition. The Tunisian uprising markedly increased economic and commercial risks. During the protest, most businesses remained closed; they re-opened only gradually after the downfall of the regime. Retailers were particularly affected by looting; likewise, the tourism sector recorded major losses as visitors fled the country. Supply-chain disruptions and damage to offices and production plants were considerable; according to a February survey published by research centre IACE, average capacity utilisation in manufacturing industry fell to 52.9% in the wake of the uprising. Moreover, several banks were downgraded by ratings agencies, thus restricting access to credit on the international markets. In addition, there is uncertainty over the fate of 175 firms owned by relatives of former President Ben Ali, with financial institutions Banque de Tunisie and Zitouna Bank being placed under caretaker management. Inevitably, payment risks for foreign companies have soared. The political success of the Tunisian revolution set a dangerous precedent for authoritarian regimes in MENA, with Egypt following a similar path: large crowds gathered in the countrys main cities to protest against deteriorating living conditions, corruption and authoritarianism; despite the relatively peaceful management of the protest by the security forces, the death toll amounted to around 150 by early February.

Under pressure from the military, on 11 February President Hosni Mubarak stepped down and handed over power to the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), led by former Minister of Defence Mohamed Hussein Tantawi. The SCAF dissolved the parliament, appointed a committee to amend the suspended constitution, and committed to holding elections within six months. Although demonstrators cheered this military coup, there are significant concerns regarding the real intentions of the SCAF, which is made up of high-ranking officers linked to the previous regime; the outcome of the transition is still extremely uncertain. As in Tunisia, the economy also ground to a halt, as most businesses shut and re-opened only after Mubaraks resignation. For several days there were shortages of staple foods and fuel, internet access was blocked and phone communications were also subject to severe disruptions. Access to ports was also suspended, with several shipping companies re-routing their container ships to other regional port facilities. Positively, Egypts unrest did not affect traffic flows through the Suez Canal, which continued as normal. Unsurprisingly, tourists and investors pulled out of Egypt; on 6 February the pound plunged to a six-year low against the US dollar. That said, FX reserves were equivalent to 7.0 months of import cover at the end of 2010 and are sufficient to cover the countrys short-term requirements. Contagion Risk in the Rest of the Region In the wake of the successful uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, the risk of protest contagion became increasingly real. Throughout February a series of demonstrations took place in Algeria, Bahrain, Iran, Jordan and Yemen, while Libya was engulfed in a violent spiral of protests and harsh military repression that left the country on the brink of civil war. The motives behind these revolts were similar: failure to address the longstanding problem of unemployment; rising inflation, which in early 2011 was again eroding households purchasing power; a growing sense of injustice, fuelled by high levels of corruption and cronyism within the various regimes; and anger towards longstanding dictatorships and political repression. Many governments tried to pre-empt the protests by adopting limited reforms: in Algeria, the authorities promised to lift the state of emergency that has been in place for almost 20 years; in Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh announced that he would not run for a further term at the next presidential elections in 2013; and in Saudi Arabia King Abdullah bin Abdul-Aziz unveiled a USD37bn package of pay rises, unemployment benefits and other social measures. Nevertheless, at the end of February the risk of contagion in MENA was still high. The situation was particularly critical in Libya, where in late February protests against leader Muammar al-Qadhafis regime spread quickly across the country; several cities in the east of the country fell in the hands of the protestors. The uprising was met with an extremely harsh military response (including the aerial bombing of protesters) and left thousands dead. Moreover, as the country plunged into chaos, foreign companies and governments began operations to repatriate non-Libyan nationals and shut down hydrocarbon production.

The Middle East crisis will have a considerable impact on the major economies of the world. Some of the implications of this revolt are as follows.

1. Unstable Oil Prices The Middle East supplies much of the World with its oil. According to energy company BPs Statistical Review of World Energy, the region sits on top of 61.1% of the worlds total oil reserves and 45.0% of total natural gas reserves, and produces 35.3% of total oil production and 18.9% of natural gas output .What happens in part of the world has its ripple effect in other part of the part. The free flow of capital goods and services across the borders has resulted in unprecedented growth of world economy particularly in Asian economies. As the unrest spreads among Middle Eastern countries like Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Yemen and Bahrain, world economy which was seeing signs of improving sentiments, has again adopted a very cautious approach. The region provides 35% of the worlds oil. Libya produces 1.7m of the worlds 88m barrels a day. International crude prices had reached a 30-month high $120 per barrel in February following the earlier turmoil in Egypt and Tunisia. Egypt owns and maintains the Suez Canal, a key port that still handles a large traffic of commercial ships, larger than the Panama Canal. A prospect of closing down of the port means an additional roundabout journey of approximately 6,000 miles, equivalent to 21 days, and consequently, additional fuel consumption. It can prove to be a chokepoint for a number of raw materials and finished goods. Of the total 35,000 ships crossing the Canal in 2009, almost 10% were oil tankers What does it mean for country like India which imports 75% of their oil needs. An increase in the price of oil can cause a steeper jump in inflation, because it has a larger weighting in the consumers baskets, 14.2%.

2. Rising Food Prices Food prices in 2011, are the highest this century, and many food producing countries are dependent on oil to fuel their agricultural production. Soya bean prices are rising, whilst wheat prices are affected. Staples like Bread, Soya beans, meats and vegetables which are imported by countries are set to continue to increase. A World Bank report recently said the rising food prices have pushed 44 million into poverty. In India, however the food inflation has come down to 11.49 per cent in second week of February from over 18 per cent in December last year.

3. Reduced GDP Higher oil prices mean more has to be spent on the essentials and amenities we depend on, unless we live in a country that produces oil. Higher oil prices act as a tax on countries that import the stuff, which would normally call for easier monetary policy. But they also raise inflation, which calls for tightening. This has a knock on effect on GDP

(Gross Domestic Products), as higher prices mean consumers have less to spend on other goods, other than essentials. The GDP of many European countries and the United States is already affected by higher taxes and the effects of austerity programs- may decrease this year.

4. Corporate Losses Many of these nations experiencing revolt have a business relationship with many of our global Corporations. One reason we saw stranded expatriates in oil rich Libya, from all over the globe. The change of leadership, and the opening of these economies, is good news for the local economies, but could mean many of the businesses that exported and provided services through the deposed leadership, face new competition, and even the prospect of losing these lucrative contracts. Indian companies with plans of setting up shop in the Middle-East have either postponed their plans or are looking to shift to a different location in the same region with a lower risk profile, say strategic business consultants. Developments in Bahrain, in particular, need to be monitored as several Indian companies have invested in that country, they said. The real risk, however, will get aggravated if the crisis spreads to countries such as Saudi Arabia, Syria and the UAE.

5. New Business Opportunities Business has been about evolving with situations. Considering the dependency of countries like India on imported oil, many see this crisis as an opportunity for renewable energy companies to grow exponentially.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Commercial Banking - Terms and Knowldg. V 1.0Dokument64 SeitenCommercial Banking - Terms and Knowldg. V 1.0Pranay JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Banking - Terms and Knowldg. V 1.0Dokument64 SeitenCommercial Banking - Terms and Knowldg. V 1.0Pranay JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial BankingDokument3 SeitenCommercial BankingPranay JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Egypt News Release (PDF Reference)Dokument2 SeitenEgypt News Release (PDF Reference)Pranay JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colavito - Ancient Atom BombsDokument31 SeitenColavito - Ancient Atom BombsJason Colavito100% (3)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Chhattisgarh Special Public Safety Bill, 2005Dokument6 SeitenThe Chhattisgarh Special Public Safety Bill, 2005Dinesh PilaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hong Kong Education Policy & Ethnic Minority GroupsDokument29 SeitenHong Kong Education Policy & Ethnic Minority GroupsWunpawngNoch keine Bewertungen

- German Management Style ExploredDokument3 SeitenGerman Management Style ExploredNaveca Ace VanNoch keine Bewertungen

- FPJ International Epaper-05-09-2022 - C - 220905 - 030225Dokument32 SeitenFPJ International Epaper-05-09-2022 - C - 220905 - 030225Sag SagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anderson - Toward A Sociology of Computational and Algorithmic JournalismDokument18 SeitenAnderson - Toward A Sociology of Computational and Algorithmic JournalismtotalfakrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Biden Impeachment Inquiry Justsecurity Matz Eisen Schneider SmithDokument25 SeitenAnalysis of Biden Impeachment Inquiry Justsecurity Matz Eisen Schneider SmithJust SecurityNoch keine Bewertungen

- Independence and Partition (1935-1947)Dokument3 SeitenIndependence and Partition (1935-1947)puneya sachdevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hard Core Power, Pleasure, and The Frenzy of The VisibleDokument340 SeitenHard Core Power, Pleasure, and The Frenzy of The VisibleRyan Gliever100% (5)

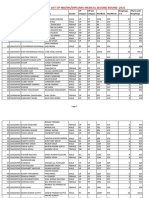

- UP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2Dokument168 SeitenUP MDMS Merit List 2021 Round2AarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tes Project Akap Monitoring Report 1 4 BonifacioDokument7 SeitenTes Project Akap Monitoring Report 1 4 BonifacioAna Carla De CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Rights: Global Politics Unit 2Dokument28 SeitenHuman Rights: Global Politics Unit 2Pau GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Singaporean Nationalism Already Existed Before 1965.'Dokument3 SeitenA Singaporean Nationalism Already Existed Before 1965.'Shalom AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Judicial Service-ThaniaDokument26 SeitenNational Judicial Service-ThaniaAnn Thania Alex100% (1)

- Affa DavitDokument2 SeitenAffa Davitmtp7389Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plunder Case vs. GMA On PCSO FundsDokument10 SeitenPlunder Case vs. GMA On PCSO FundsTeddy Casino100% (1)

- Outgoing ATMIS Djiboutian Troops Commended For Fostering Peace in SomaliaDokument3 SeitenOutgoing ATMIS Djiboutian Troops Commended For Fostering Peace in SomaliaAMISOM Public Information ServicesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education of an OrganizerDokument2 SeitenEducation of an OrganizerMalvika IyerNoch keine Bewertungen

- rtmv3 Ingles02Dokument208 Seitenrtmv3 Ingles02Fabiana MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFDokument130 SeitenGear Krieg - Axis Sourcebook PDFJason-Lloyd Trader100% (1)

- Retirement Pay PDFDokument3 SeitenRetirement Pay PDFTJ CortezNoch keine Bewertungen

- (1863) The Record of Honourable Clement Laird Vallandigham On Abolition, The Union, and The Civil WarDokument262 Seiten(1863) The Record of Honourable Clement Laird Vallandigham On Abolition, The Union, and The Civil WarHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Criminal Complaint - Stephanie BaezDokument14 SeitenCriminal Complaint - Stephanie BaezMegan ReynaNoch keine Bewertungen

- African Energy - July IssueDokument39 SeitenAfrican Energy - July IssueJohn NjorogeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sex Among Allies ReviewDokument3 SeitenSex Among Allies ReviewlbburgessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law NotesDokument118 SeitenAdmin Law NotesShavi Walters-Skeel100% (3)

- A History of England's Irish Catholic Slavery in America and Throughout The WorldDokument6 SeitenA History of England's Irish Catholic Slavery in America and Throughout The WorldConservative Report100% (1)

- Student-Father Mobile Stream DatabaseDokument20 SeitenStudent-Father Mobile Stream DatabaseDeepak DasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Teachings of The Church: Rights and ResponsibilitiesDokument23 SeitenSocial Teachings of The Church: Rights and ResponsibilitiesKê MilanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Regu PramukaDokument3 SeitenRegu Pramukazakyabdulrafi99Noch keine Bewertungen

- Vote PresentationDokument10 SeitenVote Presentationapi-548086350Noch keine Bewertungen