Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Answer Assignment 1

Hochgeladen von

naveed566Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Answer Assignment 1

Hochgeladen von

naveed566Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Whiteknights, Reading Berkshire RG6 6AW Tel: +44 (0) 118 921 4628 Fax: +44 (0) 118

921 4681

University of Reading BSc ECONOMICS Assignment 1 Module Code: Due Date: OUTLINE ANSWER QUESTION 1a This was a reflective question about the purpose of economics as a discipline. It is often students least favourite subject, due to the weight of jargon and the abstraction of much of the analysis. However, it is concerned with some of the most important features of the way our world (globally and close to home) is organised. Occasionally, when my guilty secret of being an economist is let slip, people ask, Oh, thats about cooking isnt it?. This is because many in the UK have heard of the life skills school subject home economics and know that the preparation of food is part of that subject! The reason economics is used to describe such skills is because it involves the best use of resources. Families have limited budgets and, to run a home successfully, they need to try to maximise their home comforts with the minimum of waste (in raw materials, time and effort). This includes, among other things, cookery skills. This does not mean that I am going to ask you to prepare Thai prawns for your next assignment. The economics of your course has bigger fish to fry! It is concerned with the best use of resources in the country (or indeed the world) as a whole. This focus leads to a logical set of concerns. How should production and consumption activity be organised to best use resources? What goods and services should be produced to make the best use of resources? Which resources should be devoted to which production? Who should benefit from goods and services produced? These are the focal questions of economics. These questions are couched in prescriptive terms what choices should be made? Much of economics is, in practice, about how choices are made. However, the assumption is that we need to understand how the economy actually works to be able to recommend how it might be improved. Economics is about resource choices and you should have explained the notion of scarcity and discussed the nature of the choices necessitated by that fundamental fact of life. QUESTION 1b i. You are required to make it clear what exactly the two curves are showing. Basically, the distinction is between changes in nominal gross domestic product (GDP) (single line) and changes in real GDP at 2004 prices (double line). They would coincide if the level of prices were to remain constant (i.e. if inflation were zero). When nominal GDP changes at a faster rate than real GDP (the single line curve is higher), inflation must be positive. The level of inflation can be inferred from the vertical gap between the curves. For F101ECO 22 February 2011

QF111AV12-0

instance, in 2007 the respective values are approximately 10% and 16%, which suggests an inflation rate of (116 100/110) 100, which is 5.5%. During 20042005, growth in both measures is shown to be negative and the nominal curve is below the real curve. This implies that inflation in this period was negative. Some economists call this disinflation, while others call it deflation. The fact that the real GDP measure is based on 2004 prices should make no difference to the pattern of the curve. ii. This is a very simple question if you have coped with part i. You need to appreciate that the curves show rates of change and not actual levels. Looking at the nominal curve (single line): The highest level must be in 2010, as it was 7.5% higher than in 2009, which was 11% higher than in 2008, etc. Conversely, the lowest level was in 2001, as substantial growth occurs in the next two years prior to the modest fall in the GDP level mid-period.

iii.

It appears, from the real double line, that the year subsequent to the base date of 2004 brought 1% growth, followed by a year of 8.5% growth and then up to 2007 there was 10.0% growth. Starting from 100 this gives us 100 101 109.6 120.6. This is simply a matter of compounding (not just aggregating) all the growth rates shown for real GDP (double line again). To me they look like 6.5%, 7.5%, 7.5%, -2%, 1%, 8.5%, 10%, 8%, 7% and finally 5.5%. Obviously, a reasonable margin of error is allowable on each of these. Starting at a convenient 100 we therefore get: 100 106.5 114.5 123.1 120.6 121.8 132.2 145.4 157.0 168.0 177.3 which suggests overall growth of 77.3% (close to 6% p.a.).

iv.

QUESTION 2 The study paper wording about these Slutsky effects is to be found in Paper 3447, Demand and supply, section 3.3. However, these concepts are revisited in Paper 3448, Consumers, section 6.8, where indifference curve analysis is used. Figure 18 would be appropriate. Basically, when a price changes we respond for two distinct reasons. Firstly, there is a change in the products value for money relative to other forms of expenditure. Thus, we reallocate our spending. Secondly, even if we spent the same on the product, its price change would leave us with a different amount purchasable. Cross elasticity of demand has some relevance to the substitution effect and income elasticity of demand has relevance to the real income effect. However, it is price elasticity of demand (PED) which is most closely linked to these two effects. Figure 8 in Paper 3448 (reproduced in Figure 1, here) illustrates that all determinants of PED must relate to one, or other, or both of the effects.

FIGURE 1: The determinants of price elasticity of demand

QUESTION 3 Imperfect competition is so called because it differs from perfect competition. There are therefore many different types of imperfect competition according to the permutations of imperfections that apply. Such imperfections would include: a limited number of firms a differentiated product barriers to entry imperfect information.

Permutations of these define the various forms of monopolistic competition and oligopoly. You should examine one such form in detail. Further imperfections could be included, such as: price discrimination government intervention objectives other than profit maximisation

and each would imply a slightly different kind of imperfection competition. There is also another important sense in which competition may be called imperfect and that is in its effects, particularly on the efficiency with which resources are allocated. There are welfare losses (see Paper 3458, Competition and monopoly, section 3.6 and Figure 12 for the appropriate diagram). These losses occur in both monopolistic competition and oligopoly. Such inefficiencies (from society's viewpoint) may be the result of any of the imperfect characteristics mentioned above. For example, differentiated products will mean the firm charges a price above marginal cost and therefore there will be a range of output which would have contributed more

to consumer utility (measured by willingness to pay) than to resource costs. However, this range of output is not produced. Diagrammatic models should be used to predict behaviour and illustrate the effect on economic welfare. This imperfection of effect would suggest that competition could also be imperfect if externalities exist (e.g. pollution).

QUESTION 4a The special characteristics of land are set out in Paper 0018, Property resources, section 3. The two characteristics of significance in explaining the price volatility of land are: its low (or zero) price elasticity of supply; its residual valuation.

The former means that its average value is primarily influenced by shifts in demand, and that such shifts will have most or all of their effect on price rather than quantity in the market. This is indicated in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2: Price volatility with low PES

Price

Perfectly inelastic supply

P2 Large P variability D2 P1 D1 0 NO Q variability

Quantity of land

In the case of individual plots of land, the residual nature of their value will make them particularly sensitive to changes in the profitability of development. A simple arithmetic example would illustrate this.

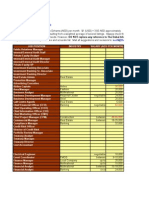

Before 10% increase in income earning potential of land Income potential Non-land costs Normal profit Land residual 1m 0.5m 0.3m 0.2m

After 10% increase in income earning potential of land Income potential Non-land costs Normal profit Land residual 1.1m 0.5m 0.3m 0.3m

It can be seen that the 10% rise in the lands earning potential creates a 50% rise in its value. You could vary the other components in the calculation which is based upon Figure 10 in Paper 0018. Students may legitimately ascribe price volatility to other factors such as planning redesignations. QUESTION 4b The arguments in favour of taxing land are covered in more detail in Module F105ECO. However, the basic argument about land rent being the definitive type of economic rent can be used here (see Paper 0018, sections 3.4 and 3.6). Taxing other factors of production typically creates a disincentive to use them. High wage taxes may discourage work, high capital taxes may discourage investment and high taxes on enterprise may discourage innovation. Such negative responses would be ways of avoiding the taxes. However, taxes on land are not so easily avoided. Indeed, it is argued that such taxes may encourage fuller use of land to be able to afford the tax. Related to this is the idea that land value is created by society, so should be, at least in part, returned to society. Contrasts with the other factors can be made.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Construction Claims and ResponsesDokument6 SeitenConstruction Claims and Responsesnaveed56667% (6)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- MoS Section A - Group 8 - Case3Dokument3 SeitenMoS Section A - Group 8 - Case3Vatsal MaheshwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Writing Complete 1st TermDokument13 SeitenClass Writing Complete 1st Termnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- I I I I I: Key Experience and BackgroundDokument4 SeitenI I I I I: Key Experience and Backgroundnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Method Statement For Earth WorkDokument22 SeitenMethod Statement For Earth Worknaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- SMP Template As of 24 March - 1Dokument33 SeitenSMP Template As of 24 March - 1naveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- 5A&B Dalvi LS Final Presentation Nov-2014Dokument21 Seiten5A&B Dalvi LS Final Presentation Nov-2014naveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Casting SchuduleDokument2 SeitenCasting Schudulenaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- HSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016Dokument2 SeitenHSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016naveed566100% (2)

- Change Management or Variation ManagementDokument14 SeitenChange Management or Variation Managementnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Monopolistic CompetitionDokument5 SeitenMonopolistic Competitionnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Finance Interest Rates For BusinessDokument22 SeitenFinance Interest Rates For Businessnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Monopolistic CompetitionDokument5 SeitenMonopolistic Competitionnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Contractor Progress PaymentDokument1 SeiteContractor Progress Paymentnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dummy Certificate - Sample DocumentDokument1 SeiteDummy Certificate - Sample Documentnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Procurement StategeDokument9 SeitenProcurement Stategenaveed566100% (1)

- HSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016Dokument2 SeitenHSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016naveed566100% (2)

- HSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016Dokument2 SeitenHSE Monthly Statisctical Report February 2016naveed566100% (2)

- Capital Budgeting TechniquesDokument11 SeitenCapital Budgeting Techniquesnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- F107ECODokument3 SeitenF107ECOnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Erogonomics FactorsDokument7 SeitenErogonomics Factorsnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Life Cycle Cost AnalysisDokument30 SeitenLife Cycle Cost AnalysisJalisman FilihanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sanitry Work-Fire Station BuildingDokument3 SeitenSanitry Work-Fire Station Buildingnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sabah Al-Salem University City - Kuwait UniversityDokument1 SeiteSabah Al-Salem University City - Kuwait Universitynaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- F107man-02 1002196Dokument20 SeitenF107man-02 1002196naveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Report - HSEDokument64 SeitenReport - HSEnaveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- F101eco 1002196Dokument10 SeitenF101eco 1002196naveed566Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thirdtrimester: X X Z X XDokument3 SeitenThirdtrimester: X X Z X XKumar KrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penarth Classified 090415Dokument3 SeitenPenarth Classified 090415Digital MediaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philippine School: A Research Presented To The Faculty of The Senior High School Department The Philippine SchoolDokument49 SeitenThe Philippine School: A Research Presented To The Faculty of The Senior High School Department The Philippine SchoolErla MarieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dialnet LaMedicionDeLaProductividadDelValorAgregado 4808514 PDFDokument9 SeitenDialnet LaMedicionDeLaProductividadDelValorAgregado 4808514 PDFVásquezRamosCarmenJannethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ad BudgetDokument27 SeitenAd Budgetshalu golyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benefits of GSTDokument18 SeitenBenefits of GSTHiteshi AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- MKTG363 SYM FinalProjectDokument30 SeitenMKTG363 SYM FinalProjectDiemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Mix of Godrej CompnayDokument81 SeitenMarketing Mix of Godrej CompnayGunjan Prajapati0% (1)

- Pele 2011 Winners by AgencyDokument17 SeitenPele 2011 Winners by AgencyHonolulu Star-AdvertiserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acctg Manual Hacienda 1Dokument66 SeitenAcctg Manual Hacienda 1William Andrew Gutiera BulaqueñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing MixDokument6 SeitenMarketing MixelianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business PlanDokument6 SeitenBusiness Planapi-278585621Noch keine Bewertungen

- Director Project Program Management in Baltimore MD Resume Gary HughesDokument3 SeitenDirector Project Program Management in Baltimore MD Resume Gary HughesGaryHughesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diva ThesisDokument96 SeitenDiva ThesisIrina ZamfirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7.pivot TableDokument107 Seiten7.pivot TableSakshi AdhaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contract of SaleDokument13 SeitenContract of SaleParas MainaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bearings in Peru: 1. ImporodDokument5 SeitenBearings in Peru: 1. ImporodSelene CarrizalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tanner Strohl ResumeDokument1 SeiteTanner Strohl Resumeapi-509881599Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nancy Grabusnik Honored As A Woman of The Month For September 2021 by P.O.W.E.R.-Professional Organization of Women of Excellence RecognizedDokument3 SeitenNancy Grabusnik Honored As A Woman of The Month For September 2021 by P.O.W.E.R.-Professional Organization of Women of Excellence RecognizedPR.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategy Implementation & Control - Unit 5Dokument92 SeitenStrategy Implementation & Control - Unit 5Bijay Poudel100% (1)

- Comparative Study of The Products of HDFC Standard Life Insurance Company and MetLife India Insurance CompanyDokument58 SeitenComparative Study of The Products of HDFC Standard Life Insurance Company and MetLife India Insurance CompanyMayank Mahajan100% (2)

- Eddie Bauer, IncDokument11 SeitenEddie Bauer, IncBharat Veer Singh Rathore50% (2)

- Iskratel Case 2002Dokument10 SeitenIskratel Case 2002Igor ČučekNoch keine Bewertungen

- CFAS PPT 24 - PAS 38 (Intangible Assets)Dokument26 SeitenCFAS PPT 24 - PAS 38 (Intangible Assets)Asheh DinsuatNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT Dallas Syllabus For mkt6380.501.11f Taught by Joseph Picken (jcp016300)Dokument12 SeitenUT Dallas Syllabus For mkt6380.501.11f Taught by Joseph Picken (jcp016300)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Sheet V - ANOVADokument5 SeitenProblem Sheet V - ANOVARuchiMuchhalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Salaries in DubaiDokument4 SeitenSalaries in DubaiHafis MhNoch keine Bewertungen

- BurningGlass Certifications 2017Dokument18 SeitenBurningGlass Certifications 2017Rahul NagrajNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Strategic Planning ProcessDokument12 SeitenThe Strategic Planning ProcessAtif KhanNoch keine Bewertungen