Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Data Analysis Methods

Hochgeladen von

Sania MirzaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Data Analysis Methods

Hochgeladen von

Sania MirzaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

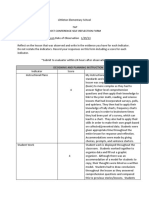

Features of Qualitative & Quantitative Research

Qualitative "All research ultimately has a qualitative grounding" - Donald Campbell

Quantitative "There's no such thing as qualitative data. Everything is either 1 or 0" - Fred Kerlinger The aim is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed. Researcher knows clearly in advance what he/she is looking for. Recommended during latter phases of research projects. All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected. Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or equipment to collect numerical data. Data is in the form of numbers and statistics. Objective seeks precise measurement & analysis of target concepts, e.g., uses surveys, questionnaires etc.

The aim is a complete, detailed description.

Researcher may only know roughly in advance what he/she is looking for. Recommended during earlier phases of research projects. The design emerges as the study unfolds.

Researcher is the data gathering instrument. Data is in the form of words, pictures or objects. Subjective - individuals interpretation of events is important ,e.g., uses participant observation, in-depth interviews etc.

Qualitative data is more 'rich', time consuming, and less able to be generalized. Researcher tends to become subjectively immersed in the subject matter.

Quantitative data is more efficient, able to test hypotheses, but may miss contextual detail. Researcher tends to remain objectively separated from the subject matter.

(the two quotes are from Miles & Huberman (1994, p. 40). Qualitative Data Analysis) Main Points

Qualitative research involves analysis of data such as words (e.g., from interviews), pictures (e.g., video), or objects (e.g., an artifact). Quantitative research involves analysis of numerical data. The strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative research are a perennial, hot debate, especially in the social sciences. The issues invoke classic 'paradigm war'. The personality / thinking style of the researcher and/or the culture of the organization is under-recognized as a key factor in preferred choice of methods. Overly focusing on the debate of "qualitative versus quantitative" frames the methods in opposition. It is important to focus also on how the techniques can be integrated, such as in mixed methods research. More good can come of social science researchers developing skills in both realms than debating which method is superior.

Qualitative Research

Paradigms There are three basic research paradigms -- positivism (quantitative, scientific approach), interpretivism, and critical science (Cantrell, n. d.).

2

Positivism, or the scientific approach, we have explored in the early parts of this course. Critical science, or the critical approach, explores the social world, critiques it, and seeks to empower the individual to overcome problems in the social world. Critical science enables people to understand how society functions and methods by which unsatisfactory aspects can be changed. We do not cover critical science in this course. Interpretivism, or the qualitative approach, is a way to gain insights through discovering meanings by improving our comprehension of the whole. Qualitative research explores the richness, depth, and complexity of phenomena. Qualitative research, broadly defined, means "any kind of research that produces findings not arrived at by means of statistical procedures or other means of quantification" (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Although acceptance of interpretivism is increasing within human movement sciences, positivism remains the dominant paradigm, as it does in other social science fields Assumptions of Interpretivism The underlying assumption of interpretivism is that the whole needs to be examined in order to understand a phenomena. Interpretivism is critical of the positivism because it seeks to collect and analyze data from parts of a phenomena and, in so doing, positivism can miss important aspects of a comprehensive understanding of the whole. Interpretivism proposes that there are multiple realities, not single realities of phenomena, and that these realities can differ across time and place. Unlike quantitative research, there is no overarching framework for how qualitative research should be conducted; rather each type of qualitative research is guided by particular philosophical stances that are taken in relation by the research to each phenomenon (O'Brien, n. d.). Main Types of Qualitative Research

Case study

Attempts to shed light on a phenomena by

3

studying indepth a single case example of the phenomena. The case can be an individual person, an event, a group, or an institution. Theory is developed inductively from a corpus of data acquired by a participantobserver. Describes the structures of experience as they present themselves to consciousness, without recourse to theory, deduction, or assumptions from other disciplines Focuses on the sociology of meaning through close field observation of sociocultural phenomena. Typically, the ethnographer focuses on a community. Systematic collection and objective evaluation of data related to past occurrences in order to test hypotheses concerning causes, effects, or trends of these events that may help to explain present events and anticipate future events. (Gay, 1996)

Grounded theory

Phenomenology

Ethnography

Historical

Main Types of Qualitative Data Collection & Analysis "Those who are not familiar with qualitative methodology may be surprised by the sheer volume of data and the detailed level of analysis that results even when research is confined to a small number of subjects" (Myers, 2002). There are three main methods of data collection:

Interactive interviewing

People asked to verbally described their experiences of phenomenon.

Written descriptions by participants

People asked to write descriptions of their experiences of phenomenon. Descriptive observations of verbal and non-verbal behavior.

Observation

Analysis begins when the data is first collected and is used to guide decisions related to further data collection. "In communicating--or generating--the data, the researcher must make the process of the study accessible and write descriptively so tacit knowledge may best be communicated through the use of rich, thick descriptions" (Myers, 2002).

Criticism of qualitative research "Qualitative studies are tools used in understanding and describing the world of human experience. Since we maintain our humanity throughout the research process, it is largely impossible to escape the subjective experience, even for the most seasoned of researchers. As we proceed through the research process, our humanness informs us and often directs us through such subtleties as intuition or 'aha' moments. Speaking about the world of human experience requires an extensive commitment in terms of time and dedication to process; however, this world is often dismissed as 'subjective' and regarded with suspicion. This paper acknowledges that small qualitative studies are not generalizable in the traditional sense, yet have redeeming qualities that set them above that requirement." "A major strength of the qualitative approach is the depth to which explorations are conducted and descriptions are written, usually resulting in sufficient details for the reader to grasp the idiosyncracies of the situation." "The ultimate aim of qualitative research is to offer a perspective of a situation and provide well-written research reports that reflect the researcher's ability to illustrate or describe the corresponding phenomenon. One of the greatest strengths of the qualitative approach is the richness and depth of explorations and descriptions."

5

- Myers (2002) Qualitative Exam Part 1 (5%): Compare and contrast two qualitative research studies in your field and interest. Include brief summaries of the studies, with relevant details about the research question and the qualitative methods. Comment on the strengths and weaknesses of these studies.

Qualitative Exam Part 2 (5%):

Describe a research question and present a qualitative research design which you think would be feasible for a Masters thesis or project. Comment on the strengths, weaknesses, and practical aspects of the design.

Qualitative Exam Part 3 (5%):

Describe a research question and a mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative methods) which you think would be feasible for a Masters thesis or project. Comment on the strengths, weaknesses, and practical aspects of the design. Make sure that your method is mixed, that is, that the techniques are meaningfully integrated.

Key Terms

Paradigms Positivism Critical science Interpretivism Grounded theory Phenomenology Ethnography Ethnoscience Historical Philosophical inquiry Action research

6

Interviewing Written descriptions Observation

Qualitative vs Quantitative analysis Corpus analysis can be broadly categorised as consisting of qualitative and quantitative analysis. In this section we'll look at both types and see the pros and cons associated with each. You should bear in mind that these two types of data analysis form different, but not necessary incompatible perspectives on corpus data. Qualitative analysis: Richness and Precision. The aim of qualitative analysis is a complete, detailed description. No attempt is made to assign frequencies to the linguistic features which are identified in the data, and rare phenomena receives (or should receive) the same amount of attention as more frequent phenomena. Qualitative analysis allows for fine distinctions to be drawn because it is not necessary to shoehorn the data into a finite number of classifications. Ambiguities, which are inherent in human language, can be recognised in the analysis. For example, the word "red" could be used in a corpus to signify the colour red, or as a political cateogorisation (e.g. socialism or communism). In a qualitative analysis both senses of red in the phrase "the red flag" could be recognised. The main disadvantage of qualitative approaches to corpus analysis is that their findings can not be extended to wider populations with the same degree of certainty that quantitative analyses can. This is because the findings of the research are not tested to discover whether they are statistically significant or due to chance. Quantitative analysis: Statistically reliable and generalisable results. In quantitative research we classify features, count them, and even construct more complex statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed. Findings can be generalised to a larger population, and direct comparisons can be made between two corpora, so long as valid sampling and significance techniques have been used. Thus, quantitative analysis allows us to discover which phenomena are likely to be genuine reflections of the behaviour of a language or variety, and which are merely chance occurences. The more basic task of just looking at a single language variety allows one to get a precise picture of the frequency and rarity of particular phenomena, and thus their relative normality or abnomrality.

7

However, the picture of the data which emerges from quantitative analysis is less rich than that obtained from qualitative analysis. For statistical purposes, classifications have to be of the hard-and-fast (so-called "Aristotelian" type). An item either belongs to class x or it doesn't. So in the above example about the phrase "the red flag" we would have to decide whether to classify "red" as "politics" or "colour". As can be seen, many linguistic terms and phenomena do not therefore belong to simple, single categories: rather they are more consistent with the recent notion of "fuzzy sets" as in the red example. Quantatitive analysis is therefore an idealisation of the data in some cases. Also, quantatitve analysis tends to sideline rare occurences. To ensure that certain statistical tests (such as chi-squared) provide reliable results, it is essential that minimum frequencies are obtained - meaning that categories may have to be collapsed into one another resulting in a loss of data richness. A recent trend From this brief discussion it can be appreciated that both qualitative and quantitative analyses have something to contribute to corpus study. There has been a recent move in social science towardsmulti-method approaches which tend to reject the narrow analytical paradigms in favour of the breadth of information which the use of more than one method may provide. In any case, as Schmied (1993) notes, a stage of qualitative research is often a precursor for quantitative analysis, since before linguistic phenomena can be classified and counted, the categories for classification must first be identified. Schmied demonstrates that corpus linguistics could benefit as much as any field from multi-method research.

The Qualitative versus Quantitative Debate In Miles and Huberman's 1994 book Qualitative Data Analysis, quantitative researcher Fred Kerlinger is quoted as saying, "There's no such thing as qualitative data. Everything is either 1 or 0" (p. 40). To this another researcher, D. T. Campbell, asserts "all research ultimately has a qualitative grounding" (p. 40). This back and forth banter among qualitative and quantitative researchers is "essentially unproductive" according to Miles and Huberman. They and many other researchers agree that these two research methods need each other more often than not. However, because typically qualitative data involves words and quantitative data involves numbers, there are some researchers who feel that one is better (or more scientific) than the other. Another major difference between the two is that qualitative research is inductive and quantitative research is deductive. In qualitative research, a hypothesis is not needed to begin research.

8

However, all quantitative research requires a hypothesis before research can begin. Another major difference between qualitative and quantitative research is the underlying assumptions about the role of the researcher. In quantitative research, the researcher is ideally an objective observer that neither participates in nor influences what is being studied. In qualitative research, however, it is thought that the researcher can learn the most about a situation by participating and/or being immersed in it. These basic underlying assumptions of both methodologies guide and sequence the types of data collection methods employed. Although there are clear differences between qualitative and quantitative approaches, some researchers maintain that the choice between using qualitative or quantitative approaches actually has less to do with methodologies than it does with positioning oneself within a particular discipline or research tradition. The difficulty of choosing a method is compounded by the fact that research is often affiliated with universities and other institutions. The findings of research projects often guide important decisions about specific practices and policies. The choice of which approach to use may reflect the interests of those conducting or benefitting from the research and the purposes for which the findings will be applied. Decisions about which kind of research method to use may also be based on the researcher's own experience and preference, the population being researched, the proposed audience for findings, time, money, and other resources available (Hathaway, 1995). Some researchers believe that qualitative and quantitative methodologies cannot be combined because the assumptions underlying each tradition are so vastly different. Other researchers think they can be used in combination only by alternating between methods: qualitative research is appropriate to answer certain kinds of questions in certain conditions and quantitative is right for others. And some researchers think that both qualitative and quantitative methods can be used simultaneously to answer a research question. To a certain extent, researchers on all sides of the debate are correct: each approach has its drawbacks. Quantitative research often "forces" responses or people into categories that might not "fit" in order to make meaning. Qualitative research, on the other hand, sometimes focuses too closely on individual results and fails to make connections to larger situations or possible causes of the results. Rather than discounting either approach for its drawbacks, though, researchers should find the most effective ways to incorporate elements of both to ensure that their studies are as accurate and thorough as possible.

It is important for researchers to realize that qualitative and quantitative methods can be used in conjunction with each other. In a study of computerassisted writing classrooms, Snyder (1995) employed both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The study was constructed according to guidelines for quantitative studies: the computer classroom was the "treatment" group and the traditional pen and paper classroom was the "control" group. Both classes contained subjects with the same characteristics from the population sampled. Both classes followed the same lesson plan and were taught by the same teacher in the same semester. The only variable used was the computers. Although Snyder set this study up as an "experiment," she used many qualitative approaches to supplement her findings. She observed both classrooms on a regular basis as a participantobserver and conducted several interviews with the teacher both during and after the semester. However, there were several problems in using this approach: the strict adherence to the same syllabus and lesson plans for both classes and the restricted access of the control group to the computers may have put some students at a disadvantage. Snyder also notes that in retrospect she should have used case studies of the students to further develop her findings. Although her study had certain flaws, Snyder insists that researchers can simultaneously employ qualitative and quantitative methods if studies are planned carefully and carried out conscientiously.

10

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Practical Research Lesson 2Dokument25 SeitenPractical Research Lesson 2Lance Go LlanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hypothesis TestingDokument60 SeitenHypothesis TestingRobiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotated BibliographyDokument4 SeitenAnnotated BibliographyMarlene POstNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spss SyllabusDokument2 SeitenSpss SyllabusBhagwati ShuklaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entity - Relationship-DiagramDokument21 SeitenEntity - Relationship-DiagramYaw Awuku AnkrahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mary Cassatt's The Sisters analyzedDokument24 SeitenMary Cassatt's The Sisters analyzedshoaib_ulhaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Nine: Qualitative Methods GuideDokument19 SeitenChapter Nine: Qualitative Methods GuideAhmed SharifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research1 Module 1 Wk1 PDFDokument3 SeitenResearch1 Module 1 Wk1 PDFjan campoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Design Mixed MethodDokument23 SeitenResearch Design Mixed MethodDr-Najmunnisa KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Selecting A Dissertation TopicDokument40 SeitenSelecting A Dissertation Topiccoachanderson08100% (1)

- IKM - Sample Size Calculation in Epid Study PDFDokument7 SeitenIKM - Sample Size Calculation in Epid Study PDFcindyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Introduction Writing: Term Paper Writing Guide Why Research Paper Editing Is ImportantDokument3 SeitenThesis Introduction Writing: Term Paper Writing Guide Why Research Paper Editing Is ImportantjoshuatroiNoch keine Bewertungen

- NJC - Toolkit - Critiquing A Quantitative Research ArticleDokument12 SeitenNJC - Toolkit - Critiquing A Quantitative Research ArticleHeather Carter-Templeton100% (1)

- Lesson No 5 Elements of Research DesignDokument26 SeitenLesson No 5 Elements of Research DesignJosephine Lourdes ValanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Khalid Mixed Methods Research WorkshopDokument32 SeitenKhalid Mixed Methods Research WorkshopKashif Raza100% (1)

- Commonly Used Statistical Terms ExplainedDokument4 SeitenCommonly Used Statistical Terms ExplainedMadison Hartfield100% (1)

- Qualitative Research: Anbony D. Cuanico, Ph.D. Graduate SchoolDokument52 SeitenQualitative Research: Anbony D. Cuanico, Ph.D. Graduate Schoollope pecayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Basic of Social Research - Study Guide 4th EditionDokument7 SeitenThe Basic of Social Research - Study Guide 4th EditionMelissa NagleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partial Correlation AnalysisDokument2 SeitenPartial Correlation AnalysisSanjana PrabhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paired t-test, correlation, regression in 38 charsDokument6 SeitenPaired t-test, correlation, regression in 38 charsvelkus2013Noch keine Bewertungen

- Types of VariablesDokument23 SeitenTypes of VariablesNaveedNoch keine Bewertungen

- HKUST COMP3211 Quiz1 SolutionDokument6 SeitenHKUST COMP3211 Quiz1 SolutionTKFNoch keine Bewertungen

- Quantitative Research MethodsDokument21 SeitenQuantitative Research MethodsElpi FerrerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Research All ChaptersDokument439 SeitenScientific Research All ChaptersEihab AlamoudiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exploratory Research DesignDokument24 SeitenExploratory Research DesignAakash SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Writing The Third Chapter "Research Methodology": By: Dr. Seyed Ali FallahchayDokument28 SeitenWriting The Third Chapter "Research Methodology": By: Dr. Seyed Ali FallahchayMr. CopernicusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 6 Inferential Statistics ModuleDokument34 SeitenGroup 6 Inferential Statistics ModuleR Jay Pangilinan Herno100% (1)

- Research Methodology: Sandeep Kr. SharmaDokument37 SeitenResearch Methodology: Sandeep Kr. Sharmashekhar_anand1235807Noch keine Bewertungen

- Admision Research Proposal TemplateDokument4 SeitenAdmision Research Proposal TemplaterahulprabhakaranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Qualitative vs. QuantitativeDokument27 SeitenQualitative vs. Quantitativecharles5544Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mixed Methods Research PDFDokument14 SeitenMixed Methods Research PDFChin Ing KhangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of Research MethodDokument4 SeitenTypes of Research MethodNataliavnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sampling Design and Terminology ExplainedDokument27 SeitenSampling Design and Terminology ExplainedsannyruraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collecting and Generating Quantitative DataDokument15 SeitenCollecting and Generating Quantitative DataRabiahtul AsiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review SHDokument7 SeitenLiterature Review SHapi-430633950Noch keine Bewertungen

- Qualitative and Quantitative ResearchDokument11 SeitenQualitative and Quantitative ResearchJeffrey ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Survey Research For EltDokument31 SeitenSurvey Research For EltParlindungan Pardede100% (3)

- Cronbach AlphaDokument5 SeitenCronbach AlphaDrRam Singh KambojNoch keine Bewertungen

- Being critical: Introducing questions, problems and limitationsDokument4 SeitenBeing critical: Introducing questions, problems and limitationsdhanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Step-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data AnalysisDokument28 SeitenStep-by-Step Guide to Qualitative Data AnalysisCinda Si IndarellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Phi CoefficientDokument1 SeitePhi CoefficientBram HarunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advice Authors Extended AbstractsDokument4 SeitenAdvice Authors Extended Abstractsadi_6294Noch keine Bewertungen

- Type I and II ErrorsDokument11 SeitenType I and II ErrorsPratik PachaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data Analysis Methods and TechniquesDokument22 SeitenData Analysis Methods and TechniquesDalel Nasri Kalboussi100% (1)

- PR 1.2 Different Types of ResearchDokument17 SeitenPR 1.2 Different Types of ResearchAizel Joyce Domingo100% (1)

- Formulating The Research ProblemDokument23 SeitenFormulating The Research ProblemTigabu YayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Statistical Significance: 2 Role in Statistical Hypothesis Test-IngDokument4 SeitenStatistical Significance: 2 Role in Statistical Hypothesis Test-IngLightcavalierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methods of Data CollectionDokument44 SeitenMethods of Data Collectionmalyn1218Noch keine Bewertungen

- Student Research Proposals 2021Dokument15 SeitenStudent Research Proposals 2021TheBoss 20Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sampling in Qualitative ResearchDokument20 SeitenSampling in Qualitative ResearchfurqanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Explaining the Importance of Background ResearchDokument3 SeitenExplaining the Importance of Background ResearchelneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation On Methods of Data CollectionDokument57 SeitenPresentation On Methods of Data CollectionTHOUFEEKNoch keine Bewertungen

- How-To Guide - Designing Academic PostersDokument18 SeitenHow-To Guide - Designing Academic PostersGOVINDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptual FrameworkDokument10 SeitenConceptual FrameworkEizzir M. BringtownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research MethodologyDokument33 SeitenResearch MethodologyEvans SieleNoch keine Bewertungen

- FOA UNIT-5 - Part .1Dokument7 SeitenFOA UNIT-5 - Part .1u2b11517Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Chapter 2 and 3Dokument17 SeitenResearch Chapter 2 and 3Ateng PhNoch keine Bewertungen

- LESSON 6 - The Research TitleDokument3 SeitenLESSON 6 - The Research TitleKaye Alejandrino - QuilalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differences Between Qualitative & Quantitative Research MethodsDokument22 SeitenDifferences Between Qualitative & Quantitative Research MethodsTadiwa KasuwaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wikipedia - Qualitative ResearchDokument3 SeitenWikipedia - Qualitative ResearchDaniel RubioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Epithalamio AnalysisDokument4 SeitenEpithalamio AnalysisSania MirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Use of Newspapers in Teaching EnglishDokument1 SeiteUse of Newspapers in Teaching EnglishSania MirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is SemanticsDokument8 SeitenWhat Is SemanticsSania MirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weight Training and Weight LossDokument8 SeitenWeight Training and Weight LossSania MirzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Claudine Padillon BSN 4Dokument2 SeitenClaudine Padillon BSN 4claudine padillonNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Com Module 1 and 2Dokument6 Seiten2018 Com Module 1 and 2Anisha BassieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post Lesson ReflectionDokument8 SeitenPost Lesson Reflectionapi-430394514Noch keine Bewertungen

- KONSTRUKTIVISME, PENGEMBANGAN MODEL, MEDIA, DAN BLENDED LEARNINGDokument28 SeitenKONSTRUKTIVISME, PENGEMBANGAN MODEL, MEDIA, DAN BLENDED LEARNINGordeNoch keine Bewertungen

- FrontmatterDokument9 SeitenFrontmatterNguyen ThanhNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBA SAMPLE 2 The Use of Simple Experiments and Mathematical Principles To Determine The Fairness of A Coin Tossed SBADokument11 SeitenSBA SAMPLE 2 The Use of Simple Experiments and Mathematical Principles To Determine The Fairness of A Coin Tossed SBAChet Jerry AckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategies to Improve MemoryDokument3 SeitenStrategies to Improve MemoryEcaterina ChiriacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mathematics Assessed Student WorkDokument37 SeitenMathematics Assessed Student WorkkhadijaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century Skills PDFDokument3 SeitenQuestionnaire Life Long Learners With 21ST Century Skills PDFHenry Buemio0% (1)

- Why Test With Users: Learn From Prototyping FeedbackDokument1 SeiteWhy Test With Users: Learn From Prototyping FeedbackAshish JainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devon Wolk ResumeDokument1 SeiteDevon Wolk Resumeapi-458025803Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of Music in Our LifeDokument2 SeitenThe Power of Music in Our LifeKenyol Mahendra100% (1)

- Project CLEAN Initiative at Pagalungan National HSDokument2 SeitenProject CLEAN Initiative at Pagalungan National HSalex dela vegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- الذكاء الاصطناعي ومستقبل التعليم عن بعدDokument14 Seitenالذكاء الاصطناعي ومستقبل التعليم عن بعدHoussem MekroudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reading: Rowell de Guia Bataan Peninsula State UniversityDokument16 SeitenReading: Rowell de Guia Bataan Peninsula State UniversityRojane FloraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kerstin Berger Case StudyDokument4 SeitenKerstin Berger Case StudySeth100% (1)

- Final Curriculum Implementation Matrix Cim World ReligionDokument5 SeitenFinal Curriculum Implementation Matrix Cim World ReligionBaby YanyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theatre For Social Change Lesson Plan OneDokument2 SeitenTheatre For Social Change Lesson Plan OneSamuel James KingsburyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Procrastination on Student Academic PerformanceDokument16 SeitenEffects of Procrastination on Student Academic PerformancealyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PolygonsDokument3 SeitenPolygonsapi-242739728Noch keine Bewertungen

- Twofold Magazine - Issue 27 - LyingDokument14 SeitenTwofold Magazine - Issue 27 - LyingcancerlaminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mastering Psychiatry 2014 (Final) 1Dokument356 SeitenMastering Psychiatry 2014 (Final) 1Melvyn Zhang100% (11)

- First Grade Lesson Plan Counting by Ones and TensDokument2 SeitenFirst Grade Lesson Plan Counting by Ones and TenskimNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education 7: ValuesDokument3 SeitenA Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in Physical Education 7: ValuesRose Glaire Alaine Tabra100% (1)

- The Magic Bullet Theory (Imc)Dokument3 SeitenThe Magic Bullet Theory (Imc)Abhishri AgarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychology From YoutubeDokument5 SeitenPsychology From YoutubeMharveeann PagalingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Miss Jenelle M. de Vera: English TeacherDokument38 SeitenMiss Jenelle M. de Vera: English Teacherromar brionesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finalized LDM Individual Development PlanDokument8 SeitenFinalized LDM Individual Development PlanJoji Matadling Tecson96% (47)

- Software Engineer Cover LetterDokument3 SeitenSoftware Engineer Cover Letternur syahkinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GTU Project Management CourseDokument3 SeitenGTU Project Management CourseAkashNoch keine Bewertungen