Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Untitled

Hochgeladen von

leichtmaneOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Untitled

Hochgeladen von

leichtmaneCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Scribd Upload a Document Explore Sign Up Log In / 17

Search Documents

Download this Document for Free Page 1 A review of rubrics for assessing online discussions Bobby Elliott Scotti sh Qualifications Authority Abstract This paper explores current practice in the assessment of online forums. It does this by reviewing the literature relating to this area of online learning, and extracting the rubrics contained within tha t literature to discover best practice as defined by the leading writers in this field. Twenty rubrics were analysed to discover their common characteristics. T hese rubrics were also reviewed for their quality in terms of validity, reliabil ity and a new characteristic called fidelity. The results of this study show that there is an inconsistent approach to the expression and definition of rubrics for the assessment of online discussions; t hat the purpose of the rubrics appears to be confused; and that their validity and, particularly, their fidelity are low. The paper concludes by recommending that rubrics continue to be used for the assessment of online discussions but that a more consistent approach is taken to their construction and definition, and that current practice is changed to impro ve validity and fidelity. The characteristics of a good marking scheme are provided to help faculty to devel op rubrics. Keywords: assessment, learning, discussion, forums, criteria, rubric , marking scheme, online, writing. A review of rubrics for assessing online discussions Page 2 Introduction This in troductory section seeks to provide background information on the key themes in this paper, which are: online discussion boards, online writing, and assessment. Educational benefits of discussion boards The educational benefits of online di scussion boards are well known and long established. Jonassen, Davison, et al (1995) expressed their suitability for lea rning as follows: The dialogue serves as an instrument for articulation because in the pro cess of explaining, clarifying, elaborating, and defending ideas, cognitive processes involving integration, elaboration and structurisation took place. Newman, Webb a nd Cochrane (1995) found that students contributed more outside material and exp eriences, and integrated ideas better, when using online discussions. Hoag and B aldwin (2000) report that students learn more in an online collaborative class t han in a face-to-face classroom, and they also acquire greater experience of tea m work, communication, time management, and technology. Some academics have clai med that asynchronous discourse is inherently selfreflective and therefore more conducive to deep learning than synchronous discou rse (see Riel, 1995, for example). Berliner (1987) reported that the increased wait t ime (the time available to discuss each topic) increases the opportunities for refle ctive learning. Swan, Shen, & Hiltz (2006) summarise the benefits of online forums: Many research ers note that students perceive online discussion as more equitable and more dem ocratic than traditional classroom discussions because it gives equal voice to a ll participants. Online asynchronous discussion also affords participants the op portunity to reflect on their classmates contributions while creating their own,

and to reflect on their own writing before posting it. This creates a certain mindfulness and reflection among students. In addition, many researchers have noted the way participants in online discussion perceive the social presence of their colleagues, creating feelings of community. Such findings have led educators to conclude that asynchronous online discussion is a particularly rich vehicle for supporting collaborative learning. Some drawbacks The reduction in constraints on time and place can result in pressures on students and faculty to read and participate in online forums (see, for example, Gabriel, 2004, Hiltz and Wellman, 1997, and Wyatt, 2005). Peters and Hewitt (2009) carried out formal interviews with 57 post-graduate students undertaking an online programme and discovered that the volume of messages was their greatest frustration. The lack of visual communication clues, disembodied learning as Dreyfus (2002) put it, can cause conflict and anxiety among learners. Mixed patterns of participat ion are common, with some learners dominating discussions and some inhibited from contributing. The text-only format of traditional discussion boards can also inh ibit interaction and can disadvantage learners with poor writing skills. A review of rubrics for assessing online discussions Page 3 Online writing Onlin e discussion boards are one instance of what has been variously described as Web 2.0 writing , online writing, digital writing or digital learning narratives, which take various forms including online forums, blogs, wikis, social networks, inst ant message logs, and virtual worlds. Many of the issues raised in this paper ar e relevant to all forms of online writing. Most of the afore-mentioned benefits of online discussion boards are, in fact, benefits of any form of (asynchronous) online writing. This new medium provides new affordances new ways of utilising t he medium to communicate and collaborate. For example, online writing makes visi ble such things as co-operation, collaboration, and self-reflection; the learners thought processes are also more apparent. The inclusion of multimedia (such as audio and video) is straight-forward. Referencing (hyperlinking) to related reso urces or information is simple. The asynchronous nature of many online communica tions makes the time and place of contributions more flexible, and provides more wait time (see above) to improve opportunities for reflective writing. The writin g may have an audience far beyond the walls of the university (perhaps a national or global audience). Authenticity can be improved by tackling real-world issues and seeking feedback from peers and experts across the world. The potential for producing authentic, coconstructed, interconnected, continuously improved, media-rich information objec ts of national or international interest is unique. These new affordances have significant implications for assessment. They provide an opportunity to assess skills that were previously considered difficult, or i mpossible, to assess using traditional approaches. Assessment of online learning The word assessment is derived from its Latin rootassidere, which means to sit bes ide. At its most basic level, assessment can be defined as observing learning (Glos sary of assessment terms, 2002). For the purposes of this paper, a more detailed definition will be used: Assessment is an on-going process aimed at understandin g and improving student learning. It involves making our expectations explicit a nd public; setting appropriate criteria and high standards for learning quality; systematically gathering, analyzing, and interpreting evidence to determine how well performanc e matches those expectations and standards; and using the resulting information to document, explain, and improve performance. (Angelo, 1995) Characteristics of ass validity reli essment Assessment is traditionally viewed from two perspectives1: ability For the purposes of this paper, a third characteristic will be considere

d:fide lity. Sadler (2009) proposed this characteristic of assessment, which is explained below. 1 Fairness (the equality of an assessment) and practicality (the fe asibility of an assessment) are sometimes also considered as characteristics of assessment. A review of rubrics for assessing online discussions Page 4 Fidelity Sadler (200 9) expresses two concerns about contemporary assessment practice. The first rela tes to continuous assessment, which he criticises for assessing students learning while they are learning rather than at the end of the learning period, when lea rning may be better internalized. As Sadler puts it: Assessment in which early un derstandings are assessed, recorded and counted, misrepresents the level of achi evement reached at the end of the course. His second criticism relates to the mat ch between assessment and learning objectives. He calls this fidelity, which he defines as: Fidelity is the extent to which elements that contribute to a course grade are correctly identified as academic achievement. He points out that, in many instances, what is rewarded is not, in fact, real ac hievements, as defined by the course objectives: Many academics cannot help but b e impressed by the prodigious time and persistence thats some students apparently invest in producing responses to an assessment task. However, effort is clearly an input variable and therefore does not fall within the definition of academic achievement. Current practice in the assessment of online learning There is grow ing concern about the relevance of current assessment practices to the present generation of learners. There appears to be a consensus in the academic community that there is a need to modernise assessment practices to embrace some of the more contemporary skills, such as collaboration, and take account of new media. But this, itself, will present challenges: Most of its advocates [of writing using Web 2.0 tools] offer no guidance on how t o conduct assessment that comes to grips with its unique features, its differenc e from previous forms of student writing, and staff marking or its academic admi nistration. [] The few extant examples appear to encourage and assess superficial learning, and to gloss over the assessment opportunities and implications of We b 2.0s distinguishing features. (Gray, Waycott, et al, 2009). This criticism is li nked to the new affordances of online writing, previously described. There is a se nse that traditional assessment is being applied to the new learning environment, neglecting the unique characteristics and opportunities presented by this environment. Marking rubrics The definition of assessment used in this paper includes making e xpectations explicit, setting appropriate criteria and systematically interpreting e vidence.The importance of clear and transparent marking criteria is well known (s ee, for example, Hounsell et al, 2007). The use of a marking rubric provides a t ransparent and objective way of assessing learning (Pickett and Dodge, 2007). Rubrics typically contain specific performan ce criteria, each assigned one or more marks, with an associated narrative to aid marking. Hazari (2004) identifies two ways of marking: analytic marking andho listic mark ing. Analytic marking involves assigning marks to each criterion; holistic marki ng is a more impressionistic approach, assigning marks as a whole, without scori ng individual criteria. Analytical criteria are normally applied to each message

Upload a Document Search Documents Follow Us!scribd.com/scribdtwitter.com/scribd facebook.com/scribd

AboutPressBlogPartnersScribd 101Web StuffSupportFAQDevelopers / APIJobsTermsCopy rightPrivacy Copyright 2011 Scribd Inc.Language:English

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Reading Wonders - Practice.ELL Reproducibles.G0k TE PDFDokument305 SeitenReading Wonders - Practice.ELL Reproducibles.G0k TE PDFDeanna Gutierrez100% (1)

- The Best Regards DavidDokument56 SeitenThe Best Regards DavidNishantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Translanguaging in Reading Instruction 1Dokument8 SeitenTranslanguaging in Reading Instruction 1api-534439517Noch keine Bewertungen

- Research Group EvaluationDokument2 SeitenResearch Group EvaluationAlexandra ShaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is TeachingDokument7 SeitenWhat Is TeachingAlexandre Andreatta100% (1)

- Dubai Energy Efficiency Training Program Presents Certified Energy Manager Course (Cem)Dokument16 SeitenDubai Energy Efficiency Training Program Presents Certified Energy Manager Course (Cem)Mohammed ShamroukhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Study On Span of ControlDokument2 SeitenCase Study On Span of Controlsheel_shaliniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Does Ragging Develop FriendshipDokument7 SeitenDoes Ragging Develop FriendshipRejas RasheedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Asean Engineer RegistrationDokument4 SeitenAsean Engineer RegistrationkatheranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kerwin C. Viray: Career ObjectivesDokument2 SeitenKerwin C. Viray: Career ObjectivesMagister AryelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managerial SkillsDokument3 SeitenManagerial SkillsFarhana Mishu67% (3)

- Uzbekistan-Education SystemDokument3 SeitenUzbekistan-Education SystemYenThiLeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alpha Xi Delta Denver Alumnae Association: President's LetterDokument8 SeitenAlpha Xi Delta Denver Alumnae Association: President's LetterStacey CumminsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Da Vinci Studio School of Creative EnterpriseDokument32 SeitenThe Da Vinci Studio School of Creative EnterpriseNHCollegeNoch keine Bewertungen

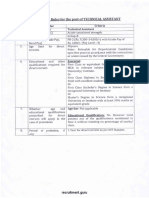

- NIT Recruitment RulesDokument9 SeitenNIT Recruitment RulesTulasiram PatraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Differentiated Instructional Reading Strategies and Annotated BibliographyDokument25 SeitenDifferentiated Instructional Reading Strategies and Annotated BibliographyShannon CookNoch keine Bewertungen

- IIT and NIT DetailsDokument25 SeitenIIT and NIT DetailsAssistant HRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Demo 2Dokument2 SeitenTeaching Demo 2api-488654377Noch keine Bewertungen

- De Luyen Thi THPT QG 2017Dokument4 SeitenDe Luyen Thi THPT QG 2017Nguyễn Thị Thùy TrangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attribute AnalysisDokument5 SeitenAttribute AnalysisSmriti KhannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd GRD Habit 6 LessonDokument2 Seiten2nd GRD Habit 6 Lessonapi-242270654Noch keine Bewertungen

- PerDev Mod1Dokument24 SeitenPerDev Mod1TJ gatmaitanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Quarter II-Module 13: Meaningful LifeDokument12 SeitenIntroduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person: Quarter II-Module 13: Meaningful LifeArien DinoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arola (2009) The Design of Web 2.0. The Rise of The Template, The Fall of Design PDFDokument11 SeitenArola (2009) The Design of Web 2.0. The Rise of The Template, The Fall of Design PDFluliexperimentNoch keine Bewertungen

- Significance of The StudyDokument2 SeitenSignificance of The Studykc_cañadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gist of RSTV Big Picture: National Education Policy 2020 - Languages, Culture & ValuesDokument3 SeitenGist of RSTV Big Picture: National Education Policy 2020 - Languages, Culture & ValuesAdwitiya MishraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 102322641, Amanda Wetherall, EDU10024Dokument7 Seiten102322641, Amanda Wetherall, EDU10024Amanda100% (1)

- 4G WeldingDokument11 Seiten4G WeldingMujahid ReanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gwinnett Schools Calendar 2016-17Dokument1 SeiteGwinnett Schools Calendar 2016-17bernardepatchNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter1 Entrepreneurship NidhiDokument23 SeitenChapter1 Entrepreneurship Nidhiusmanvirkmultan100% (3)