Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Workforce Planning in Small Local Governments

Hochgeladen von

Helen JekelleOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Workforce Planning in Small Local Governments

Hochgeladen von

Helen JekelleCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Review of Public Personnel Administration

http://rop.sagepub.com/

Workforce Planning in Small Local Governments

Enamul H. Choudhury Review of Public Personnel Administration 2007 27: 264 DOI: 10.1177/0734371X06297464 The online version of this article can be found at: http://rop.sagepub.com/content/27/3/264

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Section on Personnel Administration and Labor Relations of the American Society for Public Administration

Additional services and information for Review of Public Personnel Administration can be found at: Email Alerts: http://rop.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://rop.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://rop.sagepub.com/content/27/3/264.refs.html

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Workforce Planning in Small Local Governments

Enamul H. Choudhury

Miami University

Review of Public Personnel Administration Volume 27 Number 3 September 2007 264-280 2007 Sage Publications 10.1177/0734371X06297464 http://roppa.sagepub.com hosted at http://online.sagepub.com

The current milieu of public personnel administration is bustling with reform ideas and practices. As the public sector moves from a civil service to a human resources paradigm, adapting innovative personnel practices is increasingly becoming critical for good governance. Workforce planning (WFP) is one such innovation that allows a jurisdiction to build its long-term capacity in the face of changing work requirements, work values, technology, demography, and an array of other factors. Although the evidence on the use of WFP at the federal level is encouraging, the same is not the case at the state and local levels. There is little to nothing known about the need or the applicability of WFP in small local governments. Therefore, in the context of small local government, the article assesses the conceptual promises of WFP against the realities and capacities of governments operating at the grassroots level. Keywords: workforce planning; strategic human resource management; small local governments

orkforce planning (WFP) is a strategic planning process for human resource management. It involves taking steps for systematically matching the projected staffing needs of a jurisdiction with the available and emerging employee skills in the labor market. The growing interest in WFP is evident in both theory and practice. In texts, WFP is discussed as a component of strategic human resource management (SHRM), whereas in public agencies it has been advocated as a tool of the Government Performance and Results Act. Moreover, in academic and professional outlets, there is a growing body of literature on the status of WFP in federal, state, and large city and county governments. The current pattern of WFP in government is ad hoc and mixed (Government Performance Project [GPP], 2001; International Personnel Management Association [IPMA], 2002, p. v; Selden, 2005; Selden, Ingraham, & Jacobson, 2001). Although government units report having formal strategic planning in place, this is often not backed up with a formalized workforce plan. For example, the GPP, which rates jurisdictions on a scale of 1 to 20 (with higher scores indicating a more formal effort in adopting WFP), reports a mean state score of 7.7 (Kellough & Selden, 2003, p. 176). Within this broad discussion, which covers the federal, state, and local levels, the literature provides little or no information on the status of WFP in small local governments. This is an important focus given the fact that national or statewide studies

264

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 265

of larger local governments generally overlook the variables that are salient in smaller governments (Gianakis & McCue, 1997). For example, a recent survey of WFP practices in 97 local governments consisted mostly of large jurisdictions (Johnson & Brown, 2004). Small local governments are increasingly assuming more service responsibilities and partnering with other jurisdictions to both plan their future and address present needs. The ability to fulfill their present and future responsibilities requires small local governments to make necessary adjustments in their staffing processes and practices. Thus, WFP offers an important means of complementing the traditional civil servicebased system with the practices of SHRM. Although the theory of WFP is long on the promise of improving the management capacity of local governments, its realization rests in securing the conditions of effective implementation and adoption. For many small local governments, just as for larger ones, this frequently involves overcoming the procedural and attitudinal conditions that underscore the traditional civil service rules and regulations and the state statutes under which they operate. The adoption of WFP is particularly challenging for smaller local governments because of their distinctive characteristics. Small local governments are distinctive in terms of their size, political status, administrative capacity, and culture. They often lack the fiscal, technical, and professional capacities to adopt administrative innovations (French & Folz, 2004, p. 52). Unlike larger jurisdictions with a substantial number of professional employees, the administrative and political offices in small local governments are frequently managed through informal exchanges. In small local governments, elected and appointed officials, citizen volunteers, and part-time and contract employees frequently make up the workforce. They often do not have a separate personnel department, and, in many cases, citizen boards and commissions often substitute for professionally staffed and specialized departments (Honadle, 2001; McGuire, Rubin, Agranoff, & Richards, 1994; Russo, Waltzer, & Gump, 1987). This article focuses on small local governments because the conditions of effective human resource management at the federal, state, or large urban levels often are not a good fit for smaller jurisdictions. The discussion is intended to bring attention to the promise, prospects, and reality of smaller local governments as important users of WFP. Specifically, the discussion is framed by two basic questions. First, do small local governments perceive a need for WFP, and how do they conceptualize such need? Second, which components of WFP are considered important? The study offers an understanding of both in terms of what smaller local governments value and prefer in their practice of WFP. Specifically, this involves focusing on the staffing techniques in use rather than the normative model of WFP. For example, this could involve practicing WFP without formally invoking any of its technically specified constructs. The discussion draws on the available literature and, for illustrative purposes, also draws on data from a survey and selected interviews with local officials in southwestern Ohio.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

266 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Method and Data

The Center for Public Management and Regional Affairs at Miami University conducts an annual survey on public sector wages and benefits of Ohio local governments in a 10-county area (Butler, Warren, Montgomery, Clark, Greene, Darke, Preble, Shelby, Miami, and Clermont Counties and selected townships across the state). Periodically, the basic survey includes supplemental questions on specific issues relating to personnel management. In 2005, the supplemental questionnaire asked local officials about their views and practices concerning WFP in their jurisdictions. A total of 53 local governments responded to the 2005 supplemental questions. I selected 40 of these that had a population of fewer than 25,000. The median population of these 40 small local governments was 7,800, and the median number of full-time employees was 30. In the literature, small local governments represents jurisdictions serving populations of between 2,500 and 24,500 (French & Folz, 2004, p. 54), 5,000 to 25,000 (Gianakis & McCue, 1997), and fewer than 50,000 (Brudney & Selden, 1995). In this article, jurisdictions serving fewer than 25,000 people are considered small. The literature on WFP is characterized by a number of empirical analyses, including Johnson and Brown (2004), Pynes (2004), IPMA (2002), Gresham and Andrulis (2002), South Carolina Budget and Control Board (2000), and the International City/County Management Association (ICMA, 2000). The 2005 supplemental questionnaire in the survey included questions based on or drawn from these studies. In addition, to gain an in-depth understanding of the perceptions of local officials, structured personal interviews were conducted with the manager or assistant manager in three local governments.

WFP as Strategic Adaptation

In local governments, the professionalization of personnel practices was driven by the principles of the civil service reform movement. An elaborate system of rules, regulations, quasi-independent civil service commissions, and various statutes regulating personnel practices were designed to counter political influence and emphasize rule compliance. This system is focused on protecting personnel from the abuse of partisan politics and promoting the merit principle. The traditional system is increasingly becoming inadequate, as it was designed for a workforce facing different challenges of a different time (Pynes, 2003; Selden et al., 2001; Shafritz, Rosenbloom, Riccucci, Naff, & Hyde, 2001; Tompkins, 2002; Tompkins & Stapczynski, 2004). During a long period, this system has institutionalized a set of constraints that limits local governments adopting and practicing SHRM. For example, narrow and rigid classification plans, slow hiring processes, and procedural constraints limit investments in testing and training (Gresham & Andrulis, 2002; Selden, 2005). In

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 267

many cases, recruitment practices do not align with training strategies. Employee retention often focuses more on compensation issues than on education and flexible work arrangements (Tompkins & Stapczynski, 2004). The inadequacy also rests on a multitude of environmental factors that are propelling a shift in workforce, work technology, and work processes (Freyss, 2004; GPP, 2001; Green, 2000; ICMA, 2000; IPMA, 2002; Pynes, 2004; U.S. General Accounting Office [GAO], 2003; West & Berman, 1993). For example, even under the current reform impetus, employee development is given very little attention irrespective of the fact that skills such as communications, quality management, and customer service are considered as mission critical. Local governments recognize the need to complement the traditional approach with what is now variously described as SHRM (Freyss, 2004, p. 17; GAO, 2003, p. 2; Perry & Mesch, 1997; Pynes, 2003, p. 93; Selden et al., 2001; Tompkins & Stapczynski, 2004, p. 7). SHRM means that a jurisdiction anticipates the impact of external environmental factors on its staffing functions and aligns its staffing practices in relation to some broadly defined strategic needs (IPMA, 2002, p. x; Kellough & Selden, 2003, p. 168; McGregor, 1991, p. 33; Pynes, 2003, p. 93; Tompkins, 2002, p. 106). These staffing practices include recruitment, retention, succession planning, retirement, redeployment, compensation, and training and development functions of a jurisdiction. An important argument for change is to institute a more flexible staffing system through WFP initiatives such as narrow job classes, updating job analyses, broad banding pay structures, and using pay for performance schemes and managed competition strategies as well as development, training, and education assistance programs (Selden, 2005, p. 61).

SHRM in the Context of Small Local Government

The aim of this article is to find out whether there is a shift in incorporating SHRM in small local governments with fewer than 25,000 residents. Such governments offer some unique constraints for adopting administrative innovations such as WFP. In fact, small local governments have often been found to be the weakest in adopting administrative or technological innovations. Their weakness has been attributed to a variety of factors: the lack of political authority, political will, budgetary slack, and technical skills; and the level of professionalism, unionization, or simply their size, which prevents small local governments from implementing systems that require a larger operational scope (Brudney & Selden, 1995, p. 74; French & Folz, 2004, p. 52; Freyss, 2004; Gianakis & McCue, 1997, p. 274). Many small local governments in Ohio not only share these conditions, but they also display some distinctive features as they operate in a highly decentralized fiscal system. In national surveys, they have been found to be less innovative and professional than similar jurisdictions elsewhere. For instance, tools and techniques considered mundane elsewhere have been viewed as true innovations in Ohio (Gianakis

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

268 Review of Public Personnel Administration

& McCue, 1997, pp. 270, 282). In the GPP rating, although the average score for state adoption of WFP is quite low (7.7 out of a possible 20), Ohio scored even lower with a 4.5 score (Kellough & Selden, 2003, p. 176). Taken together, these limitations and constraints work to hinder the capacity of small local governments in Ohio to anticipate and plan for their future. They also limit their ability to invest resources for a full-fledged adoption of an untested process such as the WFP. Therefore, before we can assess what kind of WFP can be adopted and how, we need to get a clear understanding of what WFP means at this level.

The Generic WFP Model

As a tool, WFP carries different labels, criteria, and focus (ICMA, 2000, p. 2; Shafritz et al., 2001). A short definition of WFP is planning for future human resource needs now (Kurowski & Mills, 2005, p. 4). More simply, it means getting the right people in the right job at the right time (Anderson, 2004, p. 363; Pynes, 2004, p. 391). In formal terms, WFP matches the available supply of labor with the forecasted demand in light of the strategic goals of an organization (ICMA, 2000, p. 2; Pynes, 2003, p. 96). For example, the city of Virginia Beachs award-winning Workforce Planning and Development Software allows managers to produce reports detailing projected retirement statistics, workforce demographics, and vacancy reports and to tailor career development paths (Miracle, 2004, p. 449). A variety of techniques supports the four stages of the WFP model: demand, supply, gap, and solution analyses (IPMA, 2002, pp. 23-27). Demand analysis involves identifying future activities and competencies using techniques such as projecting the human resource needs of an entity. Projections may be done through sophisticated models or by simply being aware of changes in the labor market. Supply analysis examines the current and future composition of the workforce using techniques such as attrition forecast. Both demand and supply analyses are systematically matched in gap analysis to identify staffing deficiencies. This is followed with solution analysis, which identifies ways to correct the short- and long-term problems. The WFP model links staffing functions with the entire management process in terms of two component strategies (GAO, 2003, p. 2; Gresham & Andrulis, 2002, p. 3; IPMA, 2002, pp. 14-15): (a) aligning an organizations human resource needs with its mission and program goals and (b) deploying long-term strategies to acquire, develop, and retain staff for goal achievement. Different WFP models conceptualize these two components in terms of different practices (IPMA, 2002). Currently, it seems that a one-size-fits-all mentality is driving the adoption of the WFP model, particularly the models articulated by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM, 2002) and the U.S. GAO (Anderson, 2004, p. 375; GAO, 2003; Gresham & Andrulis, 2002, p. 4). However, in practice, the adoption of WFP varies from being centralized to decentralized, elective to mandated, or one time to ongoing (Anderson, 2004, pp. 363-364). Despite the variation in use, translating the generic model into practice is a much more

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 269

difficult task, especially when jurisdictions vary in terms of their environment, size, mission, and goals (GAO, 2003, p. 12; Shafritz et al., 2001, p. 138).

Conditions for the Effective Adoption of WFP

The adoption of administrative innovations in local government is driven by contextual and even idiosyncratic factors (Gianakis & McCue, 1997, p. 426; Selden, 2005, p. 65; West & Berman, 1993, p. 279). For example, many local governments embrace WFP only after considering what the results will mean or how the data will actually be used rather than simply on the merits of the theory itself (Kurowski & Mills, 2005). Besides specific contextual factors, the literature specifies a set of structural and procedural conditions for the effective adoption of WFP. These include having a clear strategy in place, having resource and management support to act on the strategy, staying motivated to overcome frustrations and failures, and keeping the focus on demonstrating clear benefits (Gresham & Andrulis, 2002, p. 4; IPMA, 2002, p. 14; Johnson & Brown, 2004; Kurowski & Mills, 2005, p. 5; Pynes, 2003, 2004; Tompkins, 2002, p. 103). It needs to be pointed out that these generic conditions apply across all levels of government; however, their specification depends on the particular context where the adoption of WFP takes place. Adequate funding and top management support. In small local governments, the condition of a clearly delineated strategic goal or a planning process is often absent. Small jurisdictions may not have or even need a separate personnel department to do such planning. In those instances where there is a department head, they perform most of the personnel functions. Therefore, at this level, what it means to strategically manage needs to be understood more in terms of informal planning and organization of the staffing functions. In many cases, the strategy is ad hoc and emerges from informal discussions, targeted recruitment effort, or learning from training programs (Tompkins & Stapczynski, 2004, p. 2). The formal WFP model calls for continuous resource support from top management. This is deemed necessary to install and maintain a systematic process of gathering, analyzing, and projecting staffing data 5 or 10 years into the future (IPMA, 2002, p. 14). However, the literature reports that WFP is not yet a high-profile concern of top management, nor does it garner the necessary budget allocation and staffing support (Gresham & Andrulis, 2002; Johnson & Brown, 2004, p. 379; Pynes, 2004). These limitations are often reinforced by the perception of political risk in investing in a technique that is yet to deliver on its promise. Flexible adaptation and clear demonstration of benefits. There is a widespread recognition that the application of WFP needs to be customized to a jurisdictions unique goals and how it does its business in general (Kurowski & Mills, 2005, p. 4; Shafritz et al., 2001, p. 147). This calls for matching WFP expectations and practices

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

270 Review of Public Personnel Administration

with a jurisdictions culture (Tompkins, 2002, p. 103). For instance, at the state level, legislative professionalism has been found to have a positive effect on the adoption of WFP, whereas unionization shows a negative effect (Kellough & Selden, 2003). Furthermore, changes in personnel practices necessitate trust and open communication to overcome the control orientation that is entrenched in the staffing process (Pynes, 2003; Tompkins, 2002). However, small jurisdictions need to be cautious in their adoption strategy. This is because, although the WFP theory is premised on coping with environmental complexity, small local governments face much less complexity, and in some cases, it may be practically absent. Small local governments also need to focus on addressing the expectations of their primary stakeholders. To do so, WFP initiatives must create visible benefits for a jurisdiction (Gresham & Andrulis, 2002, p. 10; Kurowski & Mills, 2005, p. 5). For instance, at the initial stage, a jurisdiction can focus on either its staffing gaps or the most difficult to hire positions (Anderson, 2004, p. 375). This is a crucial choice in the adoption of WFP. Making the right choice not only cushions the jurisdiction from some negative results (which are inevitable) but also builds positive support for maintaining momentum. Acting on either choice is often very difficult for small local governments because they may lack slack resources or staff time to follow through. Given that we cannot resolve these problems through theory, it is necessary to learn what the practitioners at this level think about WFP and the techniques they consider useful in addressing their staffing needs.

The Receptivity of WFP and Preference for WFP Strategies

The survey sought to identity whether and to what extent local officials value the theory and practice of WFP. In reporting the findings, the terms receptive and preference rather than awareness and support are used for the following reason. Because much of the knowledge of new administrative techniques circulates as catch phrases, the aim was not to capture simple awareness of the concept of WFP but its valuation in terms of specific applications. Thus, in this study, receptivity and preference convey the subjective attitudes of local officials (and hence, indirectly, their experience). At this nascent stage of WFP in small local governments, assessing its feasibility is more salient than prescribing strategies for adoption.

Receptivity of WFP in Small Local Governments

The survey data show that small local governments have a stable workforce. Among the jurisdictions surveyed, 54% report that the average age of their officials has remained the same, with 33% reporting that the average age increased moderately. In addition, 75% of the responding jurisdictions did not experience much turnover and report a 78% success rate in hiring their first-choice candidates. Despite

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 271

this degree of stability, local officials recognize turnover as a problem arising from the growing competition for qualified labor. When asked to identify the primary reasons for which individuals have left full-time employment in the past 5 years, compensation (22%) and better opportunities (19%) are the often-cited reasons. From the general literature on WFP, we can infer that competitiveness will intensify for some positions, leading to the creation of new positions. Other reasons for turnover that are mentioned by the respondents include personal conflict, grant running out, moving to a large city, and disciplinary dismissal. In response to the anticipated instability, small local governments do consider WFP a strategic tool to address their staffing needs and manage their programmatic functions. In the survey, local officials were asked to rate (as high, moderate, or low) a set of operational measures that generally accompany the adoption of WFP. Specifically, officials were asked to indicate the relative importance of these measures with respect to their current recruitment and retention practices. Table 1 reports the ratings of the local officials indicating the degree to which they find these measures relevant for their jurisdictions. Because not all jurisdictions responded to all questions, Tables 1 and 2 present the number of jurisdictions that responded to a particular survey question. Consistent with the literature on WFP at other levels of government, in small local government, recruitment also looms as the most pressing reason for valuing WFP. For example, the jurisdictions surveyed report that they emphasize targeted hiring (80%) to recruit the best candidate. They also indicate that public image of the jurisdiction (53%) plays an important role in effective recruitment. Thus, image is accorded more weight than what the literature suggests as the justification for valuing WFP. The more interesting case is the low ranking of flexibilitywhich is a defining pillar of SHRM. However, given the fact that red tape at this level is not a significant obstacle, the current level of flexibility may be viewed as sufficient for taking effective personnel action. For instance, one of the survey questions asked whether jurisdictions consider either restructuring or reassignment of an existing position before making a hiring decision. Of the 28 jurisdictions that responded, 79% claimed that they do. Small local governments find WFP important to remain responsive to their environment and the needs of their constituents. The survey asked local officials to identify the skill areas where they see the greatest need for recruiting competent employees. The content analysis of the responses is as follows: professional skills (27%) and technical skills (22%), management skills (30%), customer service skills (11%), and computer related skills (10%). Interviews with some local officials also point to additional factors such as the growing reliance on new technology, uncertainty of intergovernmental relationships, and generational differences in values that will be affecting their staffing functions. For instance, in relation to generational difference, one local official puts it in the following terms: Many of us dont like to take sick leave and feel it is a duty to come and complete the work.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

272 Review of Public Personnel Administration

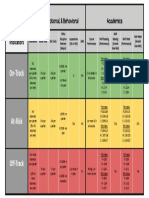

Table 1 Receptivity of Workforce Planning in Small Local Governments

Workforce Planning Techniques Targeted effort to hire Public image of the unit Competitive pay and benefit Wider pool of diverse candidates Adoption of flexible work rules Greater flexibility in rule application High (%) 80 53 51 24 28 13 Moderate (%) 20 35 46 49 53 47 Low (%) 0 12 3 27 19 40 n 35 34 35 33 32 30

Note: Because not all jurisdictions responded to all questions, the number of jurisdictions that responded to a particular survey question is mentioned separately.

However, now [new] people just call up saying they wont come. Another important concern conveyed by a different official focused on finding educated people who are willing to serve in local government. This concern is reinforced by the apprehension that fewer numbers of people are considering (public) management as a career option, especially for the senior management positions. Thus, local officials seem to be very much aware of the environmental changes that are affecting local government employment, and they are thinking about these as they assess their future condition and capacity. The local officials interviewed consider the generic model useful only when it is adapted to their local context. As one official phrased it, We want a more local, municipal WFP. Such a response underscores the need to become more flexible while continuing to operate in a system characterized by antiquated civil service regulations, testing procedures, and unionization, which impede progress toward SHRM. Strategically, jurisdictions refer to the importance of cultivating a perception of caring government through formal training in better customer service. This awareness finds an explicit recognition in the following contention:

We are not much different from others in the area except in our approach to work. We operate by the principles of high performance organization theoryoperating with a team focus, leaders involving employees at all levels in problem solving, serving customers, and doing things quickly.

Thus, we find small local governments to be not only receptive to WFP but also more realistic and progressive than what the conventional view leads us to presume.

Preference for WFP Strategies

The federal adoption of WFP remains ad hoc (IPMA, 2002, p. v). The same situation prevails in the states, large cities, and counties (GPP, 2001; Selden et al., 2001).

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 273

Table 2 Preference for Workforce Planning Strategies in Small Local Governments

Workforce Planning Techniques Recruitment Diversifying benefits Creation of a larger application pool Involving line managers/supervisors Retention Career growth opportunity Expansion of training opportunities Expansion of career paths High (%) Moderate (%) Low (%) n

34 33 33 32 23 16

47 61 30 58 67 58

19 2 37 10 10 26

32 33 30 31 30 31

Note: Because not all jurisdictions responded to all questions, the number of jurisdictions that responded to a particular survey question is mentioned separately.

At the state level, there is a growing use of technology, temporary staff, and flexibility in compensation. However, they are used more to address immediate deficiencies than to build the long-term capacity of state agencies. As with other levels of government, small local governments also value WFP. Nevertheless, it is one thing to value WFP as a concept and another thing to institutionalize the demand, supply, gap, and solution analysis in operational terms. In the survey, respondents were asked to rate (as high, moderate, or low) some WFP techniques in relation to the recruitment and retention functions of their jurisdictions. Table 2 identifies some of these techniques as a way to capture the preferences of local officials for adopting WFP strategies. Based on questions asking local officials to rate various recruitment, hiring, and retention practices, the survey data show that local officials are quite selective in their preferences. They not only weigh one strategy differently from another, but they also recognize that different strategies apply to the recruitment and retention functions. For example, under retention, they give more weight to career growth opportunity (i.e., expanding employee development opportunities such as with online coursework) than expansion of career paths (i.e., counseling or moving into new positions). In addition, diversifying benefits (a recruitment strategy) receives stronger preference than expansion of training opportunity (a retention strategy). Key to the effectiveness of adopting a WFP strategy is its role in improving staffing capacity. A variety of strategies can contribute in effecting such improvement using a larger application pool, diversifying benefits, involving line management, and expanding career paths and training opportunities. We find that one third (33%) of the jurisdictions consider these techniques to be high in importance, but except for involving line management, more consider them to be moderately important (47% and 61%, respectively). The salience of involving line managers/supervisors points to

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

274 Review of Public Personnel Administration

consultation as a critical factor in effective recruitment. On the other hand, for retention, career growth opportunity (32%) stands out as the most preferred way to sustain a qualified workforce.

Demand Analysis in Small Local Governments

Demand analysis involves the systematic identification and tracking of future competencies and the nature of the workforce and workload that will be needed in a jurisdiction. As part of the identification of demand, jurisdictions track the changes in technology, laws, and social values that will have long-term impact on their workforce and work process. Which techniques do small local governments prefer to profile their workforce? The survey data show that, although about 78% of jurisdictions are not currently experiencing much difficultly in hiring their first-choice candidates, they nevertheless consider it important to keep track of their current staffing situation. Formal tracking involves periodic review of job descriptions. However, in most cases, tracking the current workforce is informal and involves simply the supervisory evaluation of day-to-day assignments. As one administrator elaborates, Just because you can do something doesnt mean you are good at it. In the interviews, local officials report that their jurisdictions engage in some form of monitoring of skill level of their workforce, even when these skills involve only 10% of their staff capacity. For example, the manager of one jurisdiction reports anticipating changes in federal or state policies that will affect the jurisdictions local programs and services (e.g., e-government initiatives). The manager also considers changes in other jurisdictions (e.g., consolidation and/or outsourcing) and in the expectations of their constituencies as important forces shaping the jurisdictions future. To identify whether jurisdictions are keeping the future in mind, skills were divided into two categories: traditional and emergent. Under the traditional heading were included skills such as knowledge of procedures and applicable laws, writing competency, cost-control, loyalty, and esprit de corps. In contrast, under the emergent category were included skills such as computer skills, customer service skills, planning skills, and multi-tasking skills. Based on these two categories, local officials emphasized the emergent category when identifying the skills needed in the future. Within this category, management competency (e.g., people and fiscal skills and work ethic), technology competency (e.g., knowledge of GIS), and communication competency (e.g., cultural and customer service skills) received the most prominence in weighing future recruitment and training. However, there seems to be a greater concern with management competency than with technical expertise. One local official echoes the view of others by saying,

It is easy to find people with technical skills, or you can teach or train them. In fact, we use a lot of contracting services, but it is getting difficult to hire people whose values match with those of the organization.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 275

Despite the importance that local officials give to tracking demand, small local governments do not find it necessary to use a formal information system for this purpose. The general feeling is that they can get adequate information when they want it. In effect, they believe that their small size makes professional experience and professional contacts as sufficient for tracking demand. Taken together, these factors show that small local governments are not complacent with stability but open to the increasing competitive pressures and uncertainty in their environment.

Supply Analysis in Small Local Governments

Supply analysis involves identifying and tracking the supply of the future workforce that will be in need. This involves the systematic mapping of the changing environment through monitoring demographic shifts, updating the recruitment process, and using attrition forecasts. Given that, local officials view their environment as relatively stable; the survey data show that small local governments find recruitment techniques only moderately important for securing supply. This indicates that environmental turbulence is yet to become a characteristic feature of small local governments. At the same time, this also points to the fact that local officials do not simply embrace the generic model of WFP but make realistic assessment of their need. In profiling their future, small local governments prefer specific techniques to anticipate future changes. In general, they consider analyzing the impact of technology and the states budget on jobs to be more valuable than analyzing the impact of social and political trends. Their analysis includes not only the issue of competency but also the very nature of a jurisdictions core functions. For example, in the future, functions such as police, fire, emergency service, storm water management, zoning, tax administration, and engineering will require new skills that will become harder to find. In fact, many anticipate such functions to become contracted out or consolidated. Currently, some jurisdictions already contract out functions such as engineering. However, in the next 5 years, local officials anticipate new skills and competencies to grow in demand. These range from performance evaluation to computer skills. Their small size also makes it easy to anticipate the vacancies that arise from retirement or hiring freeze. They see these vacancies as an opportunity to rethink the position, and this rethinking often leads to outsourcing as a way to secure costly competencies. One jurisdiction conveys its experience in the following way:

There was an impending retirement in the police department. We learned that in the state retirement system, the person was allowed to retire but can continue to work on a rehire agreement. So we rehired him as a contractual employee.

In some areas, small local governments are adopting formal methods to assess whether a position is still needed or not. For example, one jurisdiction reports that it audits its positions in regular intervals. Three years ago, the jurisdiction audited each

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

276 Review of Public Personnel Administration

position, and it plans to audit them again in the coming year. Thus, small jurisdictions do not simply fill empty positions but rethink openings through job analysis. When a vacancy occurs, administrators do take into consideration redeploying the current staff or restructuring the position to secure the needed competencies. For example, one jurisdiction is currently rethinking its finance director position, which has experienced much turnover and plans either to reengineer the position or to spread the work to existing employees and part-time work. Interviews with officials also revealed that, in making outsourcing decisions, small local governments do consider cost savings as their primary but not their only criterion. Other criteria such as acquiring hard to get skills, particularly those that require certification (e.g., engineers and wastewater treatment plant operators), are also considered as ways to supplement the existing workforce.

Gap Analysis in Small Local Governments

Gap analysis specifies what an agency can realistically attempt based on the knowledge gathered from its demand and supply analyses. Small local governments are very much involved, often creatively, in adopting strategies to reduce the gaps. For instance, they explicitly recognize the need to upgrade the civil service testing procedures. They also conduct HR audit, job analysis, and work redesign to update job functions, direct training to targeted jobs, and measure employee workloads for making budget recommendations. Small jurisdictions not only try to identify their skill gaps but often do targeted analyses of difficult-to-hire or difficult-to-train jobs. They attempt to target where they perceive most of the gap to lie: computer use, accounting, teamwork, and interpersonal communication. One area that is gaining attention is customer service. Local officials also remain alert to the use of outsourcing, professional development, and position consolidation as contingency strategies. For example, one jurisdiction improved its customer service capacity by centralizing its clerical employees in the front office. The purpose behind such centralization was to create redundancy so that one employee can fill in for another in the event one does not show up for work. The use of gap analysis in small local governments is also demonstrated in the use of both formal and informal retention efforts. This includes preference for techniques such as using training as the primary means for upgrading skills or using vacancies as opportunities for developmental assignments. In addition, supporting and funding the professional affiliation of employees seem to be more important than techniques such as mentoring, job shadowing, or promotion-readiness evaluation. Techniques that are considered the least important include telecommuting, bringing back retirees to serve as mentors and trainers, and employing retirees for special projects. The little interest shown in career growth opportunities and telecommuting does not necessarily signal a lag in capacity on the part of these jurisdictions. Small local governments also operate through small flat organizations and

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 277

in smaller geographic space, often rural or suburban in nature. Sophisticated techniques such as telecommuting, career planning, job enrichment, or mentoring by retirees are things small local governments cannot provide and may not even need. Rather than deploying and relying on formal techniques, local officials place more emphasis on informal approaches. In small local governments, the informal approach often means redeploying persons to another position rather than losing an experienced employee. As one local official observes, We looked for ways to do it, but could not do it, because financial concerns forced us to eliminate the position. Local officials often act creatively in using positions and skills for cross-functional use. The flexible use of personnel to meet contingent program needs highlights such creativity. For instance, when there is a shift in demand for service, administrators deploy employees with the requisite skills to address the need. How such improvisation occurs is illustrated in the following example. Yard signs, as one township administrator narrates,

go up in neighborhoods on Fridays as soon as the zoning inspector leaves work. For the weekend, we simply extended the authority to other employees living in a nearby neighborhood to do the inspection. Employees take on such expanded duties because they feel a stewardship role towards their job.

Other ways in which jurisdictions informally seek to reduce gaps is by encouraging employees to volunteer for functions. According to one local official, employees in his office retooled their personnel evaluation process by doing their own research to incorporate a 360-degree evaluation. This pattern of preferences shows that small jurisdictions are actively thinking and doing what gap analysis requires. The pattern also shows that although the current emphasis is on informal techniques, the more significant the anticipated change, the more the preference moves in the direction of adopting formal techniques.

Solution Analysis in Small Local Governments

Small local governments already have in place many of the techniques that address the gaps arising from the discrepancy of demand and supply of personnel. Do they also think about the effectiveness of their techniques or incorporate new techniques to improve their staffing capacity in the future? They in fact do. Although the current pattern of application is ad hoc, the future use of WFP is viewed and valued in more holistic terms. Administrative leaders see WFP as an occasion to think about where they need to be in the future. As one local official notes, We have a specific HR person who is currently in the process of creating a more formal orientation program. The purpose is to create awareness in the organization of what the city is about. Others express the same intent in terms of making a positive impact on the community and supporting the creation of a seamless government by facilitating smooth succession in key supervisory positions.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

278 Review of Public Personnel Administration

In terms of more proximate ends, small local governments see in WFP a way to more systematically and quickly attend to their priorities through the effective delegation of staffing functions. They also seem to take a learning approach in adopting new techniques. For instance, one jurisdiction seeks out best practices through professional contacts. Small local governments see the future in terms of a more systematic effort toward WFP than what is now in place. For instance, one official reports that the jurisdiction, in keeping with its size and mission, considers data collection and analysis for WFP to be an expanded function of the department heads, assistant manager, or team rather than a specialized activity requiring a separate human resource department. Thus, small local governments are very realistic in their views on whether their current organizational culture would be supportive of the changes that WFP may bring in the future. As one administrator puts it, Some will welcome it, others will resist, and some would be in between. Although their smallness makes it relatively easier, success in adopting WFP in small local governments depends on management style and employee participation. A key issue for institutionalizing WFP is whether the elected council considers it as priority. Elected officials tend to be interested in satisfying their immediate needs; therefore, staffing innovations such as WFP are often ignored. In fact, WFP is yet to gain widespread political support at the small government level, which may also be its most significant challenge in the future.

Conclusion

Clearly, small local governments recognize the need to strengthen their human resource capacity to adapt to the changes in their environment. WFP is one such tool to serve the citizens and stakeholders of a jurisdiction. Generally, administrative innovations such as WFP address the needs of large, complex agencies at the federal or state levels. The traditional pattern that small local government either will adopt these innovations through a trickle-down process or follow a best-practice model is not supported in our analysis. In addressing the neglected domain of small local governments, we found that rather than embracing a normative model of WFP, smaller jurisdictions are proactive about their future staffing needs and think realistically in the context of their culture and capacity. Given the limitation of the data, we find that for small local governments WFP is not an entirely new concept. Therefore, they do not view it as a passing fad but consider a component of SHRM. Even though their current workforce remains stable, small local governments are informally acting in adopting the WFP strategies. The approach remains informal because of the inherent limitations in their administrative capacity and the adequacy of the existing approaches to meet current needs. Thus, it is the administrative capacity and culture of small local governments and not the prescriptive requirements of the available WFP models that define what WFP means in small local governments.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Choudhury / Workforce Planning 279

In the context of the jurisdictions surveyed, we also find that in small local governments, the meaning and importance of WFP is understood in a holistic way, although in practice these governments adopt it in a more selective manner to cope with their fiscal and institutional constraints. Although the importance of technical needs is acknowledged, local officials also convey the critical importance of the image of the jurisdiction, political climate, and changing work ethics as more salient than the conventional issues of diversity and customer service. They recognize that different strategies are needed for the recruitment and retention needs of their jurisdiction and that team involvements and empowerment are more effective strategies in WFP than formal forecasts. Such pragmatic responses point to the fact that small local governments are focused more on their present conditions than their future needs. In other words, they are acting more tactically than strategically to their changing requirements and environments. As a result, they seem not to be much inclined to adopt techniques that can strengthen their long-term capacity for acquiring and retaining the required work force. However, this observation must be buttressed by the fact that the informal and improvisational flexibility that local officials display in their current approach to WFP is an asset that helps them to cope with the constraints under which they operate.

References

Anderson, M. W. (2004). The metrics of workforce planning. Public Personnel Management, 33(4), 363-378. Brudney, J. L., & Selden, S. C. (1995). The adoption of innovation by smaller local governments: The case of computer technology. American Review of Public Administration, 25(1), 71-85. French, P. E., & Folz, D. H. (2004). Executive behavior and decision making in small U.S. cities. The American Review of Public Administration, 34(1), 52-66. Freyss, S. F. (2004). Local government operations and human resource policies: Trends and transformations. In The municipal yearbook 2004 (pp. 17-25). Washington, DC: International City/County Management Association. Gianakis, G. A., & McCue, C. P. (1997). Administrative innovation among Ohio local government finance officers. American Review of Public Administration, 27(3), 270-286. Government Performance Project. (2001). State grades. Retrieved February 20, 2004, from http://www .maxwell.syr.edu/gpp/statistics/2001_State_HRM_11.11.02.v2.htm.asp Green, M. E. (2000). Beware and prepare: The government workforce of the future. Public Personnel Management, 29(4), 435-443. Gresham, M. T., & Andrulis, J. (2002). Creating value in government through human capital management Integrating workforce planning approaches. Retrieved March 16, 2004, from http://www.ibm.com/ services/hk/igs/pdf/g510-1691-creating-value-govt-human-capital.pdf Honadle, B. W. (2001). Theoretical and practical issues of local government capacity in an era of devolution. Journal of Regional Analysis and Policy, 31(1), 77-90. International City/County Management Association. (2000). Workforce planning and development. MIS Report, 32(3), 1-17. International Personnel Management Association. (2002). Workforce planning resource guide for public sector human resource professionals. Alexandria, VA: Author.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

280 Review of Public Personnel Administration

Johnson, G. L., & Brown, J. (2004). Workforce planning not a common practice, IPMA-HR study finds. Public Personnel Management, 33(4), 379-388. Kellough, J. E., & Selden, S. C. (2003). The reinvention of public personnel administration: An analysis of the diffusion of personnel management reforms in the states. Public Administration Review, 63(2), 165-176. Kurowski, C., & Mills, F. (2005, January). Workforce planning: Making it fit. IPMA-HR News, 1, 4-5. McGregor, E. B., Jr. (1991). Strategic management of human knowledge, skills, and abilities: Workforce decision-making in the post-industrial era. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. McGuire, M., Rubin, B., Agranoff, R., & Richards, C. (1994). Building development capacity in nonmetropolitan communities. Public Administration Review, 54(5), 426-432. Miracle, K. (2004). Case study: The city of Virginia Beachs innovative tool for workforce planning. Public Personnel Management, 33(4), 449-458. Perry, J. L., & Mesch, D. J. (1997). Strategic human resource management. In C. Ban & N. Riccucci (Eds.), Public personnel management: Current concerns, future challenges (pp. 21-34). New York: Longman. Pynes, J. E. (2003). Strategic human resource management. In S. W. Hays & R. C. Kearney (Eds.), Public personnel administration: problems and prospects (pp. 93-105). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Pynes, J. E. (2004). The implementation of workforce and succession planning in the public sector. Public Personnel Management, 33(4), 389-404. Russo, P. A., Jr., Waltzer, H., & Gump, R. (1987). Rural government management and the new federalism: Local attitudes in southwestern Ohio. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 17, 147-159. Selden, S. C. (2005). Human resource management in American counties, 2002. Public Personnel Management, 34(1), 59-84. Selden, S. C., Ingraham, P., & Jacobson, W. (2001). Human resource practices in state government: Findings from a national survey. Public Administration Review, 61(5), 598-607. Shafritz, J. M., Rosenbloom, D., Riccucci, N. M., Naff, K. C., & Hyde, A. C. (2001). Human resource planning. In Personnel management in governmentPolitics and process (pp. 94-130). New York: Marcel Dekker. South Carolina Budget and Control Board. (2000). Workforce planning survey. Retrieved March 8, 2004, from http://www.ohr.sc.gov/OHR/employer/OHR-wfplan-overview.phtm Tompkins, J. (2002). Strategic human resource management: Unresolved issues. Public Personnel Management, 31(1), 95-109. Tompkins, J., & Stapczynski, A. (2004). Planning and paying for work done. In S. F. Freyss (Ed.), Human resource management in local government: An essential guide (2nd ed., pp. 1-32). Washington, DC: International City/County Management Association. U.S. General Accounting Office. (2003). Human capital: Key principles for effective strategic workforce planning. Washington, DC: Author. U.S. Office of Personnel Management. (2002). OPM workforce planning model. Retrieved March 10, 2004, from http://www.opm.gov/workforceplanning/wfpmodel.htm West, J. P., & Berman, E. (1993). Human resource strategies in local government: A survey of progress and future directions. American Review of Public Administration, 23(3), 279-297.

Enamul H. Choudhury teaches at Miami University. He has published articles in the International Journal of Public Administration and American Behavioral Scientist. He is active in the Greater Cincinnati ASPA chapter. His research interests lie in administrative theory and budget theory.

Downloaded from rop.sagepub.com by Helen Jekelle on September 12, 2010

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Public Service Motivation A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionVon EverandPublic Service Motivation A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hi5019 Strategic Information SystemsDokument9 SeitenHi5019 Strategic Information SystemsShivali RS SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Finding Human Capital: How to Recruit the Right People for Your OrganizationVon EverandFinding Human Capital: How to Recruit the Right People for Your OrganizationNoch keine Bewertungen

- Open Compensation Plan A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionVon EverandOpen Compensation Plan A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSR Corporate Social Responsibility A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionVon EverandCSR Corporate Social Responsibility A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRM and Performance: Achievements and ChallengesVon EverandHRM and Performance: Achievements and ChallengesDavid E GuestNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transformation Change A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandTransformation Change A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training and development A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandTraining and development A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Leadership A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionVon EverandBusiness Leadership A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management Effectiveness A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandManagement Effectiveness A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Bsbled401 (Amy)Dokument16 SeitenAssessment Bsbled401 (Amy)Shar KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Process Engineering A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionVon EverandBusiness Process Engineering A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Implementation Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandImplementation Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Administration A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionVon EverandBusiness Administration A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kasus Merit Pay PlanDokument1 SeiteKasus Merit Pay PlanGede Panji Suryananda100% (1)

- Assignment 2 - Consumer Research, Inc.Dokument9 SeitenAssignment 2 - Consumer Research, Inc.orestes chavez tiburcioNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Development Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandNational Development Plan A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Resource Management System Complete Self-Assessment GuideVon EverandHuman Resource Management System Complete Self-Assessment GuideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Budgeting and Planning Complete Self-Assessment GuideVon EverandBudgeting and Planning Complete Self-Assessment GuideNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument4 SeitenCase StudyAsad HaroonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Describe Four You Would Implement When Managing A Team To Ensure That All Members Are Clear On Their Responsibilities and RequirementsDokument12 SeitenDescribe Four You Would Implement When Managing A Team To Ensure That All Members Are Clear On Their Responsibilities and RequirementssumanpremNoch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Marketing Communications A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionVon EverandIntegrated Marketing Communications A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- MIS500 Assessment 3 Brief - Reflection ReportDokument7 SeitenMIS500 Assessment 3 Brief - Reflection Reportsherryy619Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lean Six Sigma: Vivekananthamoorthy N and Sankar SDokument23 SeitenLean Six Sigma: Vivekananthamoorthy N and Sankar SKrito HdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- International Strategic Management A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionVon EverandInternational Strategic Management A Complete Guide - 2020 EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Analysis of The Industrial Relations System of Russia, Taiwan, Cameroon, and VenezuelaDokument55 SeitenComparative Analysis of The Industrial Relations System of Russia, Taiwan, Cameroon, and VenezuelaToluwalope Feyisara Omidiji71% (7)

- Strategy implementation A Clear and Concise ReferenceVon EverandStrategy implementation A Clear and Concise ReferenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Capital Development in South Asia: Achievements, Prospects, and Policy ChallengesVon EverandHuman Capital Development in South Asia: Achievements, Prospects, and Policy ChallengesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Capital Investment For Better Business PerformanceVon EverandHuman Capital Investment For Better Business PerformanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Human Resource Management at SerbiaDokument14 SeitenStrategic Human Resource Management at SerbiaDavid Susilo NugrohoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Employee Surveys: Evidence-based Guidelines for Driving Organizational SuccessVon EverandStrategic Employee Surveys: Evidence-based Guidelines for Driving Organizational SuccessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Management Practices and Students' Academic Performance in Public Secondary Schools: A Case of Kathiani Sub-County, Machakos CountyDokument11 SeitenStrategic Management Practices and Students' Academic Performance in Public Secondary Schools: A Case of Kathiani Sub-County, Machakos CountyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhonda Zubas - Assignment 2 HPT Intervention For Abc WirelessDokument10 SeitenRhonda Zubas - Assignment 2 HPT Intervention For Abc Wirelessapi-278841534Noch keine Bewertungen

- Business Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipVon EverandBusiness Improvement Districts: An Introduction to 3 P CitizenshipNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psy 3711 First Midterm QuestionsDokument14 SeitenPsy 3711 First Midterm QuestionsShiv PatelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment of HRMDokument11 SeitenAssignment of HRMShadab RashidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Importance of Diversity Planning in The Future of American BusinessDokument7 SeitenImportance of Diversity Planning in The Future of American BusinessGinger RosseterNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 - Leadership and Risk-Taking Propensity Among Entrepreneurs in MsiaDokument9 Seiten2013 - Leadership and Risk-Taking Propensity Among Entrepreneurs in MsiajajaikamaruddinNoch keine Bewertungen

- MentoringDokument19 SeitenMentoringvadapalliadityaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Appraisal - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument11 SeitenPerformance Appraisal - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediaductran268100% (1)

- Career Research EssayDokument2 SeitenCareer Research Essayapi-459816116Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mayur (Stubborn) - BSBHRM513 - Assessment 5 (7!08!2020)Dokument8 SeitenMayur (Stubborn) - BSBHRM513 - Assessment 5 (7!08!2020)chakshu jainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Administrative Management in Education: Mark Gennesis B. Dela CernaDokument36 SeitenAdministrative Management in Education: Mark Gennesis B. Dela CernaMark Gennesis Dela CernaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd Grade Hidden Letters 2Dokument2 Seiten3rd Grade Hidden Letters 2Asnema BatunggaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- (The Systemic Thinking and Practice Series) Laura Fruggeri, Francesca Balestra, Elena Venturelli - Psychotherapeutic Competencies_ Techniques, Relationships, and Epistemology in Systemic Practice-RoutDokument209 Seiten(The Systemic Thinking and Practice Series) Laura Fruggeri, Francesca Balestra, Elena Venturelli - Psychotherapeutic Competencies_ Techniques, Relationships, and Epistemology in Systemic Practice-RoutTomas Torres BarberoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reaction of ChangeDokument6 SeitenReaction of ChangeConnor LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- One Step Beyond Is The Public Sector Ready PDFDokument27 SeitenOne Step Beyond Is The Public Sector Ready PDFMuhammad makhrojalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mid Term Report First Term 2014Dokument13 SeitenMid Term Report First Term 2014samclayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muhurtha Electional Astrology PDFDokument111 SeitenMuhurtha Electional Astrology PDFYo DraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of The Spirit Catches You and You Fall DownDokument4 SeitenSummary of The Spirit Catches You and You Fall DownNate Lindstrom0% (1)

- Grade 11 Curriculum Guide PDFDokument3 SeitenGrade 11 Curriculum Guide PDFChrisNoch keine Bewertungen

- English, Title, EtcDokument4 SeitenEnglish, Title, EtcRebecca FurbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CS708 Lecture HandoutsDokument202 SeitenCS708 Lecture HandoutsMuhammad Umair50% (2)

- MaC 8 (1) - 'Fake News' in Science Communication - Emotions and Strategies of Coping With Dissonance OnlineDokument12 SeitenMaC 8 (1) - 'Fake News' in Science Communication - Emotions and Strategies of Coping With Dissonance OnlineMaria MacoveiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Howard Gardner - Multiple IntelligencesDokument10 SeitenHoward Gardner - Multiple Intelligencesapi-238290146Noch keine Bewertungen

- Communicating Assurance Engagement Outcomes and Performing Follow-Up ProceduresDokument16 SeitenCommunicating Assurance Engagement Outcomes and Performing Follow-Up ProceduresNuzul DwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living TreeDokument1 SeiteLiving TreeZia PustaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Dokument6 Seiten5.3 Critical Path Method (CPM) and Program Evaluation & Review Technique (Pert)Charles VeranoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teacher Work Sample Rubrics: To Be Completed As Part of The Requirements During The Directed Teaching SemesterDokument12 SeitenTeacher Work Sample Rubrics: To Be Completed As Part of The Requirements During The Directed Teaching SemesterIbrahim KhleifatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Caitlyn Berry-CompetenciesDokument4 SeitenCaitlyn Berry-Competenciesapi-488121158Noch keine Bewertungen

- 99999Dokument18 Seiten99999Joseph BaldomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishDokument2 SeitenA Detailed Lesson Plan in EnglishMaria Vallerie FulgarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Servant LeadershipDokument67 SeitenServant LeadershipEzekiel D. Rodriguez100% (1)

- Work Orientation Seminar Parts of PortfolioDokument1 SeiteWork Orientation Seminar Parts of PortfoliochriszleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Top 10 Qualities of A Project ManagerDokument3 SeitenTop 10 Qualities of A Project ManagerAnonymous ggwJDMh8Noch keine Bewertungen

- 20 Angel Essences AttunementDokument26 Seiten20 Angel Essences AttunementTina SarupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise Effects For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Metabolic Health, Autistic Traits, and Quality of LifeDokument21 SeitenExercise Effects For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder: Metabolic Health, Autistic Traits, and Quality of LifeNatalia Fernanda Trigo EspinozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acrp - A2 Unit OutlineDokument11 SeitenAcrp - A2 Unit Outlineapi-409728205Noch keine Bewertungen

- VQescalavalores2.0 S2212144714000532 Main PDFDokument9 SeitenVQescalavalores2.0 S2212144714000532 Main PDFlorenteangelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018-11 211 Resourcelist MentalhealthDokument1 Seite2018-11 211 Resourcelist Mentalhealthapi-321657011Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ramayana The Poisonous TreeDokument755 SeitenRamayana The Poisonous TreeGopi Krishna100% (2)

- Ews 1Dokument1 SeiteEws 1api-653182023Noch keine Bewertungen