Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Violin Pedagogy

Hochgeladen von

Fadil Al TurkiOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Violin Pedagogy

Hochgeladen von

Fadil Al TurkiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Violin-Viola Pedagogy: Sevcik yes or Sevcik no.

By John Krakenberger Before going into this matter, I want to be fair with the reader: I am unconditionally pro-Sevcik, although I listen carefully to what the opponents have to say, which is, mainly: 1) It is boring, 2) it is unmusical, 3) one can get technique with tudes. If we agree with the latest advances in pedagogy, assimilating playing our instruments with high-competition sport, it is meaningless to talk about point one: Abdominals or knee-bending is not precisely an exciting activity for athletes, neither is the work at the horizontal bar for dancers. As regards the second point, one can play any rhythmic sequence musically, even if repetitive and uninteresting. Dounis, another defender of systematic training, did not allow his students to play his unmusical sequences unmusically . I dont know about Sevcik, but I presume he insisted on the same. And as regards point 3, Etudes are musical pieces. To acquire technique with music is something I reject. Maybe technique comes out winning, but will the music? So, dear reader, if you dont wish to be convinced to become pro-Sevcik, please dont read on. Youd be wasting your time. Let us get started: Otakar Sevcik (1852-1934) was and still is an object of debate. The above three points have been the reason why many pedagogues have rejected his exercises. Others, however, affirm that his studies are the fruit of a genius because they reflect a profound understanding of what playing the violin is all about. I propose to make an objective analysis, in order to incline the doubtful reader one-way or the other. After a career as violinist and teacher in Kiev and Prague, Sevcik taught at the Academy of Music in Vienna until 1919. It is well known that precisely during this period, Vienna was one of the foremost intellectual centers of Europe, where important work on the human mind and body was made. Without the scientific knowledge to which we have become accustomed in our days, Vienna boasted then of the best diagnosticians in medicine, and psychologists, which were to become world-famous. If we look for explanations for these extraordinary exploits we arrive at a single possible conclusion: These were very intelligent people, and above all, acute observers of almost fanatical curiosity. Their minute study of human behavior led to discoveries, some of them sensational, which profoundly influenced the evolution of medicine, psychology and psychiatry all over the world. It was in this environment that Sevcik found himself with the task to write a publication of his methods for learning the violin (later on transcribed for the viola by the English master Lionel Tertis). Many the majority of the methods born during this same period are no longer in use. We must ask ourselves, therefore, how it is that Sevciks work has survived until our days, being in spite of everything the most used text in violin and viola tuition. To reply to this question let us start analyzing briefly what we must demand from a methodology towards a good instrumental apprenticeship: It should go through different phases of learning, thus: 1) Get acquainted with the material, 2) Experiment with the material, 3) Assimilate material, 4) Perfect material, and 5) Automation of material. To get this done within an organic process, one should start of with a simple process, easy to assimilate, which is not the case if for mastering a certain technical aspect you have to learn a whole etude, where the musical line is usually not of masterpiece-value (some etudes are pretty poor, musically speaking). Indeed, 90% of the effort goes into learning the notes and other lateral

aspects, and only 10% is dedicated to the task one wants to get done: Acquire dexterity in this or that technical area. It is for this reason that Sevcik has systemized the apprenticeship: When it comes to the right hand, the melody used to get certain bow strokes right is always the same (you automate that in a short time) and when the left hand is concerned you work on bars or short phrases which can be repeated in seconds, and which are then accelerated by duplicating and quadruplicating the initial tempo. The basic method of Sevcik is to follow strictly the sequence 1) to 5) mentioned in the paragraph above. You can set out comfortably, with time to spare, and as you advance, time gets shorter; things precipitate, and movements get more complicated, taking you to automatism without you noticing it. Since you start out slowly and easily, the perception in your mind is: No problem here and this feeling prevails. That is very important! In another article I mentioned that in the not too distant future it will be the neurologists who will tell us which methods for learning to play the violin are efficacious and which are not: I am absolutely sure that Sevciks methods will get kudos for being the most effective in existence. I have so far alluded only to op.1 & 2 (fingers and bowing, respectively). To give some satisfaction to the enemies of Sevcik Ill admit that the material for beginners (op. 6) is a little on the arid side, not suited for the youngsters of the second millennium. There is plenty of good material for beginners, which is up to date, and which gives the youngsters an incentive to continue studying, including Sevcik when the moment is ripe. Recommendable material for beginners will be part of another article. At this stage I should still mention op 2 N4 (for 4-5th year students) to get a good bowing technique via training of the left-hand wrist. And another indispensable exercise is op. 8, which caters to shifting positions and which, strangely enough, is used in places where op. 1 and op. 2 are frowned upon. I dont understand the logic: op.8 is as schematic as the others. But just as the others enormously useful. I hope nobody gets the idea to work only Sevcik and nothing else. That would be a fatal mistake. The acquisition of a good technique must at all times be at the service of music and should not fill more than half of the students efforts. It is the same with sports: You have to train but you also have to play. Each aspect should get its due. Before ending I would like to repeat an anecdote of the first half of the 20th century: Carl Flesch, the celebrated pedagogue, had an extremely gifted pupil called Henryk Szering. Following his masters request, Szering went through the whole work of Sevcik and those who have heard him I was fortunate to play the Mozart Duos for violin/viola with him will have realized that this helped him to become one of the top fiddlers of the world but that it did in no way damage his musicality, and less still his outstanding tonal quality. Of course there are other ways to learn how to play. The 100.000 dollar question is, with which method do we waste less time. In our ever faster moving world, time is becoming scarcer by the day. If before the age of 18 one has not been able to play all the Kreutzer studies, all the Rode caprices, and the 24 pieces of the op.35 by Dont, having previously overcome the technical difficulties posed, the student will not be able to aspire towards a career of a successful soloist. To get this done, the shortest way is, in my opinion, the one shown by Sevcik. To start playing childrens tunes at the age of 5 is indispensable, and if this brings the will and the pleasure to persevere, Sevcik can be started on as early as with 7-8 years, depending on the maturity of the pupil. You can then begin with Kayser etudes, preparatory of

Kreutzer,at the age of 12. Sevcik makes this possible. I dont know any alternative method that will get us there, except maybe other equally schematic methods such as Dounis. I have no doubt that during the 3rd millennium training methods for sports and learning instruments will converge. What is surprising is that Sevcik found precisely this way almost 100 years ago, and this speaks very well of his intelligence and genius.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Violin & Viola - Tecnica Correcta Del ArcoDokument119 SeitenViolin & Viola - Tecnica Correcta Del ArcoSilvana IbarraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tadeusz Wronski On Practice PDFDokument10 SeitenTadeusz Wronski On Practice PDFRafael Muñoz-Torrero100% (3)

- The Violin: Some Account of That Leading Instrument and Its Most Eminent Professors, from Its Earliest Date to the Present Time; with Hints to Amateurs, Anecdotes, etcVon EverandThe Violin: Some Account of That Leading Instrument and Its Most Eminent Professors, from Its Earliest Date to the Present Time; with Hints to Amateurs, Anecdotes, etcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Left Hand ChecklistDokument1 SeiteViolin Left Hand ChecklistNikkia CoxNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Violin and Its Technique - As a Means to the Interpretation of MusicVon EverandThe Violin and Its Technique - As a Means to the Interpretation of MusicBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- Tartini - Violin ConcertosDokument13 SeitenTartini - Violin ConcertosEdinei GracieleNoch keine Bewertungen

- About SevcikDokument21 SeitenAbout SevcikamiraliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violins and Violin Makers: Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the ViolinVon EverandViolins and Violin Makers: Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the ViolinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Repertoire List UNFINISHEDDokument3 SeitenViolin Repertoire List UNFINISHEDquietfool50% (2)

- The Development of the Violin Idiom in 17th Century Italian Solo SonatasDokument46 SeitenThe Development of the Violin Idiom in 17th Century Italian Solo SonatasWynton0535Noch keine Bewertungen

- Approaching The Ševčík Studies - ViolinSchoolDokument2 SeitenApproaching The Ševčík Studies - ViolinSchoolMichael LeydarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin RepertoireDokument7 SeitenViolin RepertoireWhy BotherNoch keine Bewertungen

- George Gemünder's Progress in Violin Making: With Interesting Facts Concerning the Art and Its Critics in GeneralVon EverandGeorge Gemünder's Progress in Violin Making: With Interesting Facts Concerning the Art and Its Critics in GeneralNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Methods and EtudesDokument2 SeitenViolin Methods and EtudesVicente Wehbe100% (1)

- How to Study Fiorillo: A detailed, descriptive analysis of how to practice these studies, based upon the best teachings of representative, modern violin playingVon EverandHow to Study Fiorillo: A detailed, descriptive analysis of how to practice these studies, based upon the best teachings of representative, modern violin playingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Von EverandViolin Playing As I Teach It (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Bewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (3)

- "Crazy Eights" - Exercises For A 4-Note Finger PatternDokument1 Seite"Crazy Eights" - Exercises For A 4-Note Finger PatternRafael VideiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Influence of The Bow On Aperiodicity of Violin NotesDokument1 SeiteThe Influence of The Bow On Aperiodicity of Violin NoteschellestteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Making 'The Strad' Library, No. IX.Von EverandViolin Making 'The Strad' Library, No. IX.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Choosing violin literature for students of different levelsDokument2 SeitenChoosing violin literature for students of different levelsBobi BoboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Signor Paganini Solo Violin Manual (Kontakt)Dokument5 SeitenSignor Paganini Solo Violin Manual (Kontakt)Garth NeustadterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Resource RepDokument10 SeitenViolin Resource Repnessa246Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Play Rode CapricesDokument4 SeitenHow To Play Rode CapricesBruna Caroline SouzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Methodology for developing the right hand Part 3Dokument27 SeitenMethodology for developing the right hand Part 3Xabier Lopez de Munain100% (2)

- Staccato - One of The Most Controversial Elements of Right-Hand Technique - Premium Feature - The StradDokument5 SeitenStaccato - One of The Most Controversial Elements of Right-Hand Technique - Premium Feature - The StradnanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aaron Rosand On How To Produce A Beautiful ToneDokument4 SeitenAaron Rosand On How To Produce A Beautiful ToneMaria Elena GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Play ViolinDokument5 SeitenHow To Play ViolinJasmineKitchenNoch keine Bewertungen

- IMSLP407370 PMLP593895 Courv Technicsofviolin EdDokument142 SeitenIMSLP407370 PMLP593895 Courv Technicsofviolin EdThiago PassosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Simon Fischer - Article - Improving at Any Age and StageDokument3 SeitenSimon Fischer - Article - Improving at Any Age and StageTaiana RaederNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bow, Its History, Manufacture and Use 'The Strad' Library, No. III.Von EverandThe Bow, Its History, Manufacture and Use 'The Strad' Library, No. III.Bewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Kato Havas Research PaperDokument6 SeitenKato Havas Research Paperapi-272908366Noch keine Bewertungen

- 100 Best Violin Song ListDokument13 Seiten100 Best Violin Song ListBabuBalaramanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cello Care Guide: How to Tune, Rosin, Clean Your CelloDokument3 SeitenCello Care Guide: How to Tune, Rosin, Clean Your CelloFebie DevinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Methods and Studies Sheet Music Collection CDDokument8 SeitenViolin Methods and Studies Sheet Music Collection CDdigitalsheetplusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Camilla: A Tale of a Violin: Being the Artist Life of Camilla UrsoVon EverandCamilla: A Tale of a Violin: Being the Artist Life of Camilla UrsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin ExcerptsDokument10 SeitenViolin ExcerptsZsolt Magyar100% (1)

- Violins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.Von EverandViolins and Violin Makers Biographical Dictionary of the Great Italian Artistes, their Followers and Imitators, to the present time. With Essays on Important Subjects Connected with the Violin.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Handbookofviolin00schruoft PDFDokument204 SeitenHandbookofviolin00schruoft PDFAngel AlvaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developing Beautiful Vibrato for String StudentsDokument3 SeitenDeveloping Beautiful Vibrato for String StudentsDaniel SandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bouncing The Bow: BasicsDokument2 SeitenBouncing The Bow: BasicsMarie MayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heejung Lee: Violin Portamento - An Analysis of Its Use by Master Violinists in Selected Nineteenth-Century ConcertiDokument27 SeitenHeejung Lee: Violin Portamento - An Analysis of Its Use by Master Violinists in Selected Nineteenth-Century ConcertieightronNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Physics of the Violin and Its Defining Influence Upon TechnicDokument93 SeitenThe Physics of the Violin and Its Defining Influence Upon TechnicRafael Muñoz-TorreroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of The ViolinDokument4 SeitenThe History of The ViolinJuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Violin Playing - How to Achieve SuccessVon EverandThe Art of Violin Playing - How to Achieve SuccessBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Best of Technique: BowingDokument3 SeitenThe Best of Technique: BowingosmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Fingering in The 18th CenturyDokument18 SeitenViolin Fingering in The 18th CenturyjaschamilsteinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin Methods and Etudes - ViolinmasterclassDokument3 SeitenViolin Methods and Etudes - ViolinmasterclassBenjamim alvesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 50 Contoh Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 5 SD Inggris OnlineDokument6 Seiten50 Contoh Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas 5 SD Inggris OnlineDorJonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tom Sawyer - SupaduDokument16 SeitenTom Sawyer - SupaduCecilia GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan For ETDokument4 SeitenLesson Plan For ETramla_hassan123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sla PaperDokument3 SeitenSla Paperapi-257595875Noch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Updated 2018Dokument3 SeitenResume Updated 2018api-307254141Noch keine Bewertungen

- Re-enrollment Intent Form ReturnDokument3 SeitenRe-enrollment Intent Form ReturnMairos Kunze BongaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 From 9781111771379 p02 Lores PDFDokument22 SeitenChapter 1 From 9781111771379 p02 Lores PDFkarladianputri4820100% (1)

- Erasmus Policy StatementDokument3 SeitenErasmus Policy StatementomerkemalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fads, Fashions, and Folderol in PsychologyDokument10 SeitenFads, Fashions, and Folderol in PsychologyDan SimonetNoch keine Bewertungen

- LMS Student GuideDokument33 SeitenLMS Student GuideRahim_karimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1 TOEFL Excercise: Choose The Best Answer For Multi-Choice QuestionDokument19 SeitenLesson 1 TOEFL Excercise: Choose The Best Answer For Multi-Choice QuestionFeby Ayu Kusuma DewiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Quality Handwashing ChildrenDokument10 SeitenTeaching Quality Handwashing ChildrenOscar CocNoch keine Bewertungen

- College Readiness of Senior High School StudentsDokument10 SeitenCollege Readiness of Senior High School StudentsBea C. Masujer83% (6)

- The Bowdoin Orient - Vol. 146, No. 4 - September 30, 2016Dokument15 SeitenThe Bowdoin Orient - Vol. 146, No. 4 - September 30, 2016bowdoinorientNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHBE486-686 Fall 2015 - Syllabus & CalendarDokument6 SeitenCHBE486-686 Fall 2015 - Syllabus & CalendarguadelupehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lauren Carew ResumeDokument1 SeiteLauren Carew ResumeLauren CarewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Movement Education PPDokument7 SeitenMovement Education PPapi-318644885Noch keine Bewertungen

- General Manual of Accreditation NBA PDFDokument78 SeitenGeneral Manual of Accreditation NBA PDFravinderreddynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pal MCQDokument4 SeitenPal MCQkylie_isme0% (1)

- FS Detailed Lesson PlanDokument18 SeitenFS Detailed Lesson PlanMeryll83% (6)

- Ten Metacognitive Teaching StrategiesDokument20 SeitenTen Metacognitive Teaching StrategiesMark Joseph Nepomuceno Cometa100% (2)

- Fraternity ViolenceDokument4 SeitenFraternity ViolenceArmiRoseValenciaJuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spe 615 Lesson 2 PlanDokument3 SeitenSpe 615 Lesson 2 Planapi-302304245Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Instruction Plan 1Dokument3 SeitenSample Instruction Plan 1api-341636057Noch keine Bewertungen

- Newsletter 127 - 09.09.11Dokument2 SeitenNewsletter 127 - 09.09.11stbedescwNoch keine Bewertungen

- AC05 ModelDokument5 SeitenAC05 ModelVenkatram PrabhuNoch keine Bewertungen

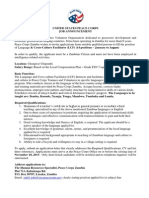

- Peace Corps Language & Cross-Culture Facilitator (LCF) (14 Positions - January To August)Dokument2 SeitenPeace Corps Language & Cross-Culture Facilitator (LCF) (14 Positions - January To August)Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Course Outline-SI 2017Dokument4 SeitenCourse Outline-SI 2017Aravind ParanthamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cusat - Admission Notification - Cat 2018: Cochin University of Science & TechnologyDokument1 SeiteCusat - Admission Notification - Cat 2018: Cochin University of Science & Technologyjozf princeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Learner'S Class Card: Deped Tambayan PHDokument2 SeitenLearner'S Class Card: Deped Tambayan PHGelle100% (1)