Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Phenomenon of Architecture in Cultures in Change

Hochgeladen von

Les TariOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Phenomenon of Architecture in Cultures in Change

Hochgeladen von

Les TariCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

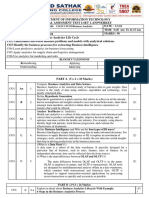

Build. Sci.

Vol. 7, pp. 291-294. Pergamon Press 1972. Printed in Great Britain

BOOK REVIEWS

The Phenomenon of Architecture in Cultures in Change

DAVID O A K L E Y Pergamon Press, Oxford (1970). 370 pp. 4.50

O A K L E Y GIVES in this book his overview of architecture; it is primarily autobiographical in its sources, arising from the experience of a traditionally-orientated education responding to the problems confronted as a professional architect and as an educationalist. The need to respond was urgent and in sharp focus as the context was predominantly in the under-developed countries. In the early fifties, architectural education was still totally concerned with the design of buildings, although, at the AA, this had been widened to include all scales of the urban environment of the industrialized countries. There was only a vague inkling that some vital factor was being overlooked, but there was wide dissatisfaction with what was considered an inadequate education. During this period, there was a trend for a proportion of students to work overseas. For these people, the confrontation with the problems encountered in the new environment had a dynamic effect, at the least a readjustment was required, but in the more extreme situations, it was clear that the problems were totally different from those anticipated by the educational programme. Oakley's experience with low cost housing in an extreme climate being a case of the latter, where the degree of technical complexity and the social and economic framework had not been foreseen by any school curriculum of that time. In Oakley's case, his professional work resuited in a most useful book, "Tropical Houses, A Guide to Their Design". This type of experience was repeated in all the developing countries where insufficient numbers of professionals were called upon to solve such problems as resettlement, urbanization, or self-help, low cost housing. In these situations, it was manifest that architecture had no adequate theoretical base and lacked technical competence. The professional was forced to realize-if he had not already done so--that his education had given him no preparation for the over-riding importance of the social aspects of all these problems. In the present book, Oakley attempts both to document and tabulate the problems encountered in designing for the built environment, and also to 291

discuss the basis of an architectural theory. In spite of his statement in the introduction, the predominant and recurring theme in the book is building design. This concern with building as the end object of architecture is a contributory factor in preventing any proper analysis of "the phenomenon". However, the book recognizes that in a developing country (not uniquely, but usually far more clearly) the relationship between the social structure and its elements and the physical environment and its artifacts is governed by the social structure. As Pierre Dansereau has said elsewhere, "Urban development is a process that carries a heavy scientific and technological load, but in which all the levers are of a socio-economic nature". To understand these levers and, from this, to be able to describe the "phenomenon of architecture", needs a more profound and a different set of basic concepts than one which can arise from the traditional preconceptions and theories of architectural design. Oakley, himself, recognizes the need for a conceptual structure. In the section on education, he states, "Without theory, we cannot effectively teach", but in the same section of the book, he also says, "Theory is a policy". In the same section, a diagram draws a parallel between the science of materials, the theory of structures, and the resultant means of analysis and computation, based upon the theories, with the theory of environment and of architecture resulting in design method. Structural engineering has a set of objective and scientific theories upon which are based the means of analysis and computation used by the engineering professions. In the sense of a theory as a verifiable, consistent, and objective statement describing the behaviour of a phenomenon, no theory of the environment or of architecture exists. Instead, we have policies, which may be opportunist, pragmatic, in accordance with some philosophy, or just personal opinions. There are, therefore, no working techniques which can be based upon theories. We have design methods which, traditionally, were craft and aesthetic based and, to a large extent, relied on the faculty of

292

Book Reviews

intuition. More recently, design methods have been devised, loaned from other disciplines, or from management techniques and applied to the problem of environment and architecture. The effect of the development during the sixties of design method and of such books as Norberg Schultz's "Intentions in Architecture", has been to draw attention to the fact that architectural design has very much in common with problem-solving in general and to make one aware that problemsolving has to operate within a context. The major determinant of this context is nearly always socialpolitical. Whilst the general problems of physical design are becoming more demanding, it is also necessary to find means of operating in the socialpolitical field, if the work of the physical designer is to have any relevance. This has been borne out by experience in the developing countries. " P e r m a n e n t " buildings as the end object of architectural design activity have been proved obsolete in "'cultures in change". Indeed, if one gives consideration to this problem, this is almost self-evident. One had hoped that Oakley would have stated this more categorically than he has. As he says, " M a n y of the problems of an architect arise because a building is expected to have a long life". He points out that, in such acute situations as the urban footholder, flexibility and change are a basic requirement. Today, flexibility and even indeterminacy are found as requirements in other situations than in under-

developed countries. It is increasingly the normal requirement in commercial and social building programmes of the industrialized countries. The book attempts to be all-inclusive and, by naming one of the chapters, "Intentions", suggests an unfortunate comparison with Norberg Schultz. Like Norberg Schultz before him, he cannot produce a new or illuminating synthesis or concept. Such a synthesis is clearly going to take many contributions, such as Oakley's, before it begins to emerge, but it is important and valuable that the attempt be made, as it is here. It would have been far more effective if rather drastic editing had been carried out to reduce the volume, the inconsistencies, and the jargon. Much of the material should be found useful, especially to students in their early years. The book seems aimed largely at this level, but the experience behind the contents and the contents themselves would justify and call for more mature treatment. However, because the author so clearly holds the view that the traditional role of the architect is still the appropriate one, what he has to say should have all the more impact on staff and students in schools where the broader implications of the present situation are only being acknowledged with reluctance.

MICHAEL LLOYD

Land Use Consultant.

Fundamentals of Structural Theory

C O U L L and D Y K E S McGraw-Hill, New York (1972). 348 pp. T H E P R O L I F E R A T I O N of textbooks on Structural Analysis places any author at a disadvantage. The reader invariably becomes more discerning and wants to know what is different about a new edition which might make it more attractive than existing volumes. Fundamentals of Structural Theory by Coull and Dykes is designed as a first text of an undergraduate course in Structures. Chapter 1 on the Scope of Structural Engineering focuses the attention on idealisations carried out in structural analysis, and the behaviour of structures under load. The illustrative diagrams are good, and more could possibly have been included. Principles of statics and bending of beams are well covered in Chapters 2 and 3, but Chapter 4 on Stress and Strain is possibly unnecessary and confusing at such an early stage. There seems to be a weak link between this treatment of stress and strain and Chapter 5 on Flexural Stresses and Deformation (and indeed with other Chapters). Chapters 6 and 7 form a good introduction to the analysis of Statically Indeterminate Structures, the topic dealt with under headings of Flexibility and Stiffness in Chapters 8 and 9. The whole book is well written, well illustrated with diagrams and solved examples and uses SI units throughout. A surprising omission is a treatment of elastic instability--a reader learns something of the behaviour of frames and beams but not struts! Perhaps the second edition will rectify this omission. The book should prove popular with staff and students alike and is a very good buy for 3"25. F. SAWKO

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- JNKI-SOP-004-Welder Continuity Procedure - RevisionDokument3 SeitenJNKI-SOP-004-Welder Continuity Procedure - RevisionAvishek GuptaNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. Objectives:: Peh11Fh-Iia-T-8 Peh11Fh-Iia-T-12 Peh11Fh-Iid-T-14Dokument2 SeitenI. Objectives:: Peh11Fh-Iia-T-8 Peh11Fh-Iia-T-12 Peh11Fh-Iid-T-14John Paolo Ventura100% (2)

- PDFDokument827 SeitenPDFPrince SanjuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teachers' Perception Towards The Use of Classroom-BasedDokument16 SeitenTeachers' Perception Towards The Use of Classroom-BasedDwi Yanti ManaluNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rouse On The Typological MethodDokument4 SeitenRouse On The Typological MethodLuciusQuietusNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestDokument84 SeitenGeneral Knowledge Solved Mcqs Practice TestUmber Ismail82% (11)

- Adina Lundquist ResumeDokument2 SeitenAdina Lundquist Resumeapi-252114142Noch keine Bewertungen

- SRM Curricula 2018 Branchwise PDFDokument110 SeitenSRM Curricula 2018 Branchwise PDFrushibmr197856040% (1)

- Teaching Methods in ScienceDokument4 SeitenTeaching Methods in ScienceJavy mae masbateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effectiveness of Talent Management at BRACDokument40 SeitenEffectiveness of Talent Management at BRACM.N.G Al FirojNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar and StructureDokument5 SeitenGrammar and StructureAini ZahraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thinking Outside The Box CaseDokument3 SeitenThinking Outside The Box CaseTan Novinna56% (9)

- Prof. N. R. Madhava Menon Asian Jural Conclave 2021-2022Dokument37 SeitenProf. N. R. Madhava Menon Asian Jural Conclave 2021-2022Shrajan RawatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 8 Lesson PlansDokument46 SeitenGrade 8 Lesson PlansArlene Resurreccion100% (1)

- Olimpiada 2015 Engleza Judeteana Suceava Clasa A Viiia SubiecteDokument3 SeitenOlimpiada 2015 Engleza Judeteana Suceava Clasa A Viiia SubiecteAnthony AdamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCW331 BA IAT 1 Set 1 & Set 2 QuestionsDokument19 SeitenCCW331 BA IAT 1 Set 1 & Set 2 Questionsmnishanth2184Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mycom Nims ProptimaDokument4 SeitenMycom Nims ProptimasamnemriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book Review OutlineDokument2 SeitenBook Review OutlineMetiu LuisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section Code Schedule Fees Amount: TotalDokument1 SeiteSection Code Schedule Fees Amount: TotalHeart SebNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bathing Your Baby: When Should Newborns Get Their First Bath?Dokument5 SeitenBathing Your Baby: When Should Newborns Get Their First Bath?Glads D. Ferrer-JimlanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kathakali and Mudras DocumentDokument23 SeitenKathakali and Mudras DocumentRasool ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emma Watson Bachelor ThesisDokument4 SeitenEmma Watson Bachelor Thesissheenacrouchmurfreesboro100% (2)

- Linear Functions WorksheetDokument9 SeitenLinear Functions Worksheetapi-2877922340% (2)

- Electricity & Magnetism SyllabusDokument5 SeitenElectricity & Magnetism SyllabusShivendra SachdevaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisDokument1 SeiteBambang National High School Remedial Exam in Poetry AnalysisShai ReenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyperbits Songwriting Cheat SheetDokument1 SeiteHyperbits Songwriting Cheat SheetJonathan Krief100% (1)

- 18Th Iukl Convocation 2022 Date: 19 March 2022 Venue: Multipurpose Hall, IUKLDokument2 Seiten18Th Iukl Convocation 2022 Date: 19 March 2022 Venue: Multipurpose Hall, IUKLQi YeongNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaDokument3 SeitenJames Mallinson - On Modern Yoga's Sūryanamaskāra and VinyāsaHenningNoch keine Bewertungen

- N. J. Smelser, P. B. Baltes - International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioral Sciences-Pergamon (2001)Dokument1.775 SeitenN. J. Smelser, P. B. Baltes - International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioral Sciences-Pergamon (2001)André MartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employment News 24 November - 30 November 2018Dokument32 SeitenEmployment News 24 November - 30 November 2018ganeshNoch keine Bewertungen