Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Designing Visual Recognition For The Brand

Hochgeladen von

nguoilaanhsangcuadoitoi_theoneOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Designing Visual Recognition For The Brand

Hochgeladen von

nguoilaanhsangcuadoitoi_theoneCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622 r 2009 Product Development & Management Association

Designing Visual Recognition for the Brand

Toni-Matti Karjalainen and Dirk Snelders

The present paper examines how companies strategically employ design to create visual recognition of their brands core values. To address this question, an explorative in-depth case study was carried out concerning the strategic design efforts of two companies: Nokia (mobile phones) and Volvo (passenger cars). It was found that these two companies fostered design philosophies that lay out which approach to design and which design features are expressive of the core brand values. The communication of value through design was modeled as a process of semantic transformation. This process species how meaning is created by design in a three-way relation among design features, brand values, and the interpretation by a potential customer. By analyzing the design effort of Nokia and Volvo with the help of this model, it is shown that control over the process of semantic transformation enabled managers in both companies to make strategic decisions over the type, strength, and generality of the relation between design features and brand values. Another result is that the embodiment of brand values in a design can be strategically organized around lead products. Such products serve as reference points for what the brand stands for and can be used as such during subsequent new product development (NPD) projects for other products in the brand portfolio. The design philosophy of Nokia was found to depart from that of Volvo. Nokia had a bigger product portfolio and served more market segments. It therefore had to apply its design features more exibly over its product portfolio, and in many of its designs the relation between design features and brand values was more implicit. Six key drivers for the differences between the two companies were derived from the data. Two external drivers were identied that relate to the product category, and four internal drivers were found to stem from the companies past and present brand management strategies. These drivers show that the design of visual recognition for the brand depends on the particular circumstances of the company and that it is tightly connected to strategic decision making on branding. These results are relevant for brand, product, and design managers, because they provide two good examples of companies that have organized their design efforts in such a way that they communicate the core values of their brands. Other companies can learn from these examples by considering why these two companies acted as they did and how their communication goals of product design were aligned to those of brand management.

Introduction

ecognition is key in a competitive market. In a situation of high competition, markets are often saturated by a constant ow of signs and messages from numerous brands. As a consequence, the creation and management of recognition for the brand becomes a major communication objective. Companies have set out to achieve brand recognition through various means. Product design is among these, and it has been put forward as a main ingredient in fostering a strong visual identity for a brand (Schmitt and Simonson, 1997; Stompff, 2003) and in creating brand value (Borja de Mozota, 2004).

Address correspondence to: Toni-Matti Karjalainen, IDBM Program, Helsinki School of Economics, P.O. Box 1210 FI-00101, Helsinki, Finland. Tel.: 358 50 357 4047. Email: toni-matti.karjalainen@hse.. The authors thank Oscar Person, Maria Saaksjarvi, and three anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this paper.

There are many examples of companies who have successfully communicated their brand values through product design. The Caterpillar brand, for example, communicates its core brand values of comfort and performance not only through its advertising, website, and slogan (Industry leading comfort and performance) but also in the design of its products. Caterpillar has ensured that its products are comfortable to use. Just as Caterpillar shoes have warm and soft padding on the inside, so the operator cabins of Caterpillars trucks and loaders have been tted with soft interiors and come with noise and dust prevention features. Furthermore, the sturdy color scheme and logo signal that the products perform well in tough situations. These design aspects apply as much to the heavy machines the company produces as to its shoes, which are targeted at the consumer market. Thus, Caterpillars core brand values are connected to recognizable and meaningful aspects of its designs.

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

This paper looks at how companies strategically aim for visual brand recognition through design. Recognition is a mode of attention dened by Krippendorff (2005, p. 91) as identifying something by its kind (name) and in view of the use to which it could be put. Note that this denition is somewhat different from denitions of recognition used in the past in advertising or marketing research (e.g., Du Plessis, 1994; Finn, 1988; Singh, Rothschild, and Churchill, 1988). In these elds, recognition has often been dened as a weak (aided) measure of a consumers memorization of an advertising message or a product, and it is typically juxtaposed to recall a strong (unaided) measure of this. This implies that in advertising and marketing research recognition is regarded as a type of declarative knowledge, established by a consumer who states that a certain advertisement or product has been seen or noted before. Krippendorffs denition, used in this paper, is somewhat broader, in that it describes recognition as a process of identication (connected to the work of Biederman and colleagues on visual recognition of faces; e.g., Biederman, 1987; Biederman and Ju, 1988) that results from semantic memory (abling classication of the product) as well as procedural memory (which helps to understand product usage). In addition, the process of recognition can be conscious or unconscious, and therefore consumers can recognize the product and its features without much awareness of it. Thus, the term recognition here includes both conscious (declarative) and unconscious (implicit) knowledge of a product, about both what the product is and what one can do with it.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES Dr. Toni-Matti Karjalainen holds the degrees of Doctor of Arts (art and design) from the University of Art and Design Helsinki and M.Sc. (economics) from the Helsinki School of Economics. He works as research director of the International Design Business Management (IDBM) Program at the Helsinki School of Economics and also has several years experience as project manager at the Business Innovation Technology (BIT) Research Centre at the Helsinki University of Technology. His research on product design, design semantics, brand management, and new product development is conducted in close collaboration with international companies. Dr. Dirk Snelders is associate professor of marketing at the Department of Product Innovation Management at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. His background is psychology, and his current research interests focus on the role of design in market research. Dr. Snelders has published earlier on consumer decision making, consumer perceptions of abstract product attributes, aesthetic product judgments, and the role of novelty and surprise in design.

Across different industries, scholars have looked at the role of the visual appearance of products in creating recognition for the brand. From the viewpoint of strategic management, design can be used to reect corporate and brand values, to develop greater consistency over the product range, and to dene the distinguishing attributes of brands and sub-brands in the companys brand portfolio (Kotler and Rath, 1984; Olson, Cooper, and Slater, 1998). However, it is unclear how companies aim for the recognition of brand value through the visual design of their products. An important starting point for exploring this issue is a series of case studies by Ravasi and Lojacono (2005) that looked at how companies organize their strategic design effort. Their study shows the importance of a design philosophy that establishes a connection among the core capabilities of the company, its strategy, and brand image. This paper examines how such a design philosophy can be an instrument in creating visual recognizable designs that communicate the brands core values. The key question in this paper is the following: How can companies strategically employ design to create visual recognition of the brands core values? The departure point for our analysis of visual brand recognition is a model of semantic transformation, which allows for an in-depth analysis of how design can communicate the brand message. The existence and working of the process described in this model is then demonstrated by two case studies at Nokia and Volvo. These case studies show how the core brand values of these two companies are transformed into a visual design language for new products and how this involves an array of strategic decisions that are partly made before, and partly during, new product development (NPD). In addition, this paper corroborates Ravasi and Lojaconos (2005) earlier nding that a design philosophy provides the strategic basis for establishing a coherent visual identity for the brand. A last contribution is the nding that the stage of strategic renewal requires a process of semantic transformation that is more sensitive to issues of brand heritage and that is organized around socalled lead products. For lead products, the design effort of the company implies a focus on product features that have more explicit and more widely understood references to the core brand values. Such products serve as internal and external reference points for what the brand stands for, and they can be used as such during subsequent NPD projects that receive less design-strategic attention. Taken together, an overview is provided of the deployment of a design

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

philosophy, and of design itself, for the strategic purpose of creating brand recognition. These results are relevant for brand, product, and design managers, because they provide two good examples of companies that have organized their design efforts in such a way that they communicate the core values of their brands. Other companies can learn from these examples by considering how the communication goals of product design can be aligned to those of brand management. Managing the translation of brand values into the design of a product requires an understanding of what designers in a team are doing when they express brand value through product design. Both in NPD and during stages of brand strategic renewal, managers can benet from the insight that design communicates brand value in its own way and that the direction of the design process needs its own targets, checks, and balances.

Intentional Communication through Design

Design is but one of the media through which a company can communicate its core brand values. According to Aaker (1996), the communication of brand value should be done in a synchronized way, so that all communication channels deliver a concerted brand message to customers. This interactional or holistic perspective on brands (for an overview of brand perspectives, see Harkins, Coleman, and Thomas, 1998; Harris and de Chernatony, 2001; Louro and Cunha, 2001) implies that product and brand meaning are intertwined and that together they lead to a powerful mix of associations that point to the core brand values. In product design, the brand message is composed of a number of product features (hereafter called design features) that embody the core brand values. Together with the other communication media, the design features represent the brands identity. If the design features contribute to the desired communication, other forms, like advertising, can be used more effectively and efciently (Mooy and Robben, 2002). Kreuzbauer and Malter (2005) stress that the connection between the design features and brand value is based on more than repeated exposure. Building on the work of Barsalou (1999), Biedermann (1987), and Zaltman (1997), these authors argue that brand recognition is not purely an exercise of semantic classication based on a set of otherwise arbitrary design features. Instead, they point to the relevance of the design features themselves in codetermining the mean-

ing of the brand. Kreuzbauer and Malter speak of embodied cognition in this respect, by which they mean that the identication of products as members of a brand is dependent on visual appearance, which can carry a set of associations of its own. In this sense, the design features should be seen as a direct embodiment of (interlinked) product and brand associations, capable of communicating core brand values of their own accord, and in their own special way. Product design can thus play an important role as a persistent and nonarbitrary reminder of the brands core values. In this sense products can be regarded as language and their features as talking to people (Oppenheimer, 2005). All manufactured products can be seen as stating something through their design, intentionally or unintentionally, passively or actively (Giard, 1990). The intentional view of design is that of a strategic activity, concerned with how things ought to be, and devising artifacts to attain goals (Simon, 2001). This intentional, value-based view of design implies that design has a strategic, goal-oriented character and that, in a business setting, it should function in coordination with other strategic intentions of the company. In a multiple case study among 11 companies that had recently undergone a process of design-driven renewal, Ravasi and Lojacono (2005) looked more closely at the strategic role of design. For these authors, design has the potential to drive strategic innovation on the basis of a design philosophy. Such a philosophy comprises a stylistic identity (based on value-based design features) and core design principles (a coherent set of beliefs and principles about the companys approach to design). A design philosophy is one of the driving forces of strategic renewal in a company, other forces being the companys core capabilities, its competitive scope (as expressed by the core brand values), and its strategic intent. For Ravasi and Lojacono (p. 71), it is imperative that the design philosophy co-evolves with these other forces, to help designers relate their work to broader issues of competition and market positioning.

Semantic Transformation: From Strategic Intent to Value-Based Design Features

The relation between brand strategy and product design is established through acts of semantic transformation (Karjalainen, 2004). Through these acts, qualitative brand descriptions are transformed into value-based design features, and these generate the intended meaning of products. The notion of semantic

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

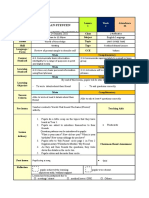

design feature

R O

brand value

interpretation context

Figure 1. The ROI Framework for the Analysis of Brand References in Design

transformation is derived from design semantics, which deals with the issue of how meaning is formed and mediated by signs that are embodied in products and recognized by others. In this eld there exist a variety of approaches toward product analysis to help designers understand how their work becomes meaningful to others (Krippendorff, 1989, 2005; Mono, 1997; Muller, 2001; Steffen, 2000; Vihma, 1995). With few exceptions (Warell, 2001), this literature has looked primarily at the communication between individual designers and society at large. Here the potential of semantic transformation is explored to function as a model for the deliberate effort of companies to communicate specic brand values to customer target groups. The theory of signs by Peirce (1955) and Peirce Edition Project (1998) provides a potential entry point to the semantic analysis of products (Karjalainen, 2004; Vihma, 1995; Warell, 2001; Wickstrom, 2002). The theory suggests that the process of signication (the attribution of meaning) is regarded as a triadic relationship among a Representamen (a perceptible object, R), an Object (of reference, O), and an Interpretant (the effect of the sign, I). Meaning is constructed through this triadic interaction. Applied to design, R can be regarded as a design feature that functions as a manifestation of the sign through its properties (e.g., form, shape, color), while O relates to a brand value with which the design element has a reference relation (Figure 1). For example, specic design features of Nike running shoes (R) can be a manifestation of the dynamic orientation of the Nike brand (O). The context of interpretation (I) comprises the subjective realm of the interpreter and the environment in which the interpretation is made. Three dimensions of the semantic transformation process play a role in this. Genuine and Stringed References. RO relations have a bidirectional nature, which means that design features create associations that connect the product

with specic brand values, and, at the same time, the brand values and their historical representations strongly affect the interpretation of the design features. This latter process, from historic brand value to feature interpretation, can be regarded as an interpretation bias, since it implies that the meaning of design features will always be affected by expectations set by the brand. As a consequence, the relation between design features and brand value is often stringed; that is, the associations that the design features evoke are themselves entangled with additional associations evoked by the brand. As a group these associations create a thematic connection between the design and the brand values. In contrast, a direct genuine reference of a design feature would be the rst (unbiased) association that a design feature brings to mind (after Peirce, 1955). Stringed references are usually culturally formed and time and context dependent. As such, stringed references are as much a product of the market as of the company, and control over them is very difcult. Still, companies can make use of stringed references under some circumstances. This is when (parts of) stringed references are based on coupled associations, which are sets of (often two) associations that frequently co-occur in products and that have become predictable and manipulable. Coupling can bring new interpretations to an initially simple reference relation (Janlert and Stolterman, 1997). For example, chrome details in cars or aluminum in mobile phones are coupled with the association of premium quality. Through coupling, companies may exert some control over stringed references, and this may allow them to communicate brand values through design in more ingenious, and less direct, ways. Explicit and Implicit References. Recognition of the core brand values can be built through both explicit and implicit visual references (Karjalainen, 2004; see also Crilly, 2005). Explicit references are embedded in design features that designers implement with the intention of being immediately perceived and recognized. These are often features in the product that have relatively distinct object boundaries (e.g., the kidney grille and quad headlights of BMW cars) or that are repeated over a large portion of the product (e.g., the variety of concave and convex shark surfaces on the body of recent BMW cars). Implicit references are based on features not so readily distinguished in the product but implemented with the intention of being inherently perceived and

10

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

recognized without customers being consciously aware of them. These references are based on design features that are not easily detected by uninformed customers. However, when implicit references are applied to a design, they can still make sense, be it more intuitively. For these references, the recognition process may not be unlike that for the recognition of a human face, which has been shown to be based for a large part on unconscious processing and on facial features that people are not aware of (Rakover and Cahlon, 2001). The socalled Hofmeister kink of BMW is an example of a reference that is implicit for most consumers. This small bend in the rear window in the C-pillar of almost all BMW saloon cars since the 1960s, named after a former director of design at BMW, creates the impression that the back of the car sits precisely on the rear-wheel axis. Even after detection most people may still not be aware how important the kink is for their perception of a powerful, rear-wheel driven car. Complete and Partial Attribution of Brand Characteristics. Attribution by customers is an important aspect of the interpretation context. Characteristics whose attribution is close to universal can be regarded as so-called complete characteristics (Janlert and Stolterman, 1997). Certain visual features entail rather complete attribution. Such features can be inherent either to human nature or to culturally established codes. For example, rounded forms and warm colors can suggest that a product has a warm, friendly, and protective character (ibid., p. 299). Specic shapes and forms can also entail complete attributions that are categoryspecic. For instance, street and off-road motorbikes can be recognized through specic form elements (Kreuzbauer and Malter, 2005), and specic packaging design can express the taste of the dessert it contains (Smets and Overbeeke, 1995). Partial characteristics, in turn, have a lesser scope of attribution. These characteristics cannot be used successfully beyond a limited group of customers. Outside this group, the interpretation of the brand reference will be uncertain. In other words, partial characteristics involve right (in this case, brand-specic) references among a limited number of customers and are arbitrary outside this group of subjects.

changes) over the entire product line, or even over the entire product portfolio of a brand. However, the level of consistency that is sought over the product line or portfolio can differ strongly between brands and industries and perhaps even between different parts of the world. Some companies have a high consistency strategy for the design of their products. Brands such as BMW, Jaguar, Citroen, Apple, Bang & Olufsen, and Braun have clearly recognizable design features that are repeated over their product lines and portfolios. Brands such as Toyota, Nissan, Ford, Sony, Panasonic, and Samsung have selected a more exible strategy with a focus on the design of individual products. Some products in the product portfolio may also be more central to the identity of a brand than others. Such lead products (or agship products) strongly incorporate the core values of the brand (Ealey and Troyano, 1997). With respect to this, Kapferer (1992) notes that almost all the major brands have pivotal products in their portfolio that best transmit the meaning of the brand. One example of such a lead product is the Volkswagen Golf (or Rabbit in the United States). The Golf was one of the rst hatchback cars to arrive on the market, and it was an instant and lasting success. To date, ve Golf generations have gone through evolutionary changes, but all have held onto a number of design features that represent German engineering quality, functional design, and good value for money. The example of the Golf shows that products can become lead products by creating a strong brand presence on the market, either through a high sales volume or through the special experience they bring to customers. A historical role for lead products is to establish an authentic heritage for the brand. Thus, the main design challenge from the product line and portfolio viewpoint is to decide how to employ valuebased design features in the product line-up of the brand and how to manage this over successive product generations. From this perspective, it is concluded that not all products in the present and historic product line and portfolio will contribute to the visual recognition of brand values in the same way, to the same extent, or at the same time.

The Construction of Product Lines and Portfolios

Value-based design features not only exist in single products: they can also be replicated (with some

Method

Two topics were identied above concerning the strategic management of brand recognition through

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

11

visual design features: the type of brand references in design and the organization of these references in product portfolios and product lines. To address these topics, an explorative in-depth case study was carried out concerning the strategic design efforts of two companies: Nokia (mobile phones) and Volvo (passenger cars). Three objectives were dened for the case studies: (1) To describe and illustrate the strategies of Nokia and Volvo for creating visual brand recognition through design. (2) To identify the key drivers behind these strategies and the case-specic variation in how these drivers exert their inuence. (3) To identify the implications of these strategies for the management of brand recognition through product design.

introduced in 1998 and the rst car to unfold Volvos new design direction, won the European Automotive Design Award (voted by professional car designers and design students from 33 countries) in the following year. The award was justied by a press release stating that the Volvo S80 represents a radical change without breaking the continuity of Volvo design and that the design has been more successful in synthesizing the past and the future than any other car in 1998 (Volvo Press Release, 1999). The design effort of both companies was extensive, but it was expected that there would be differences in their approach to product design because they operated in different industries and held different market positions. Thus the two cases had great potential to supplement each other, leading to greater depth and trustworthiness of the analysis.

Case Selection

The selection of the two cases was based on purposive and theoretical sampling, so that the cases were deliberately chosen and varied on a theoretically made distinction (Silverman, 2000). Strong, wellestablished brands of durable products with signicant attention to industrial design were selected. In particular, the aim was to nd companies that regard product design as a key instrument for creating visual brand recognition. Nokia was chosen as the rst case. The company had become the global leader in mobile phones, among other things through heavy emphasis on product design as a competitive factor. From early on, Nokia had emphasized design next to technological development (Ainamo and Pantzar, 2000). More importantly, the wealth of meanings attributed to mobile phones and their connection to the brand identity of Nokia made the company an appropriate starting point for our study. Already in the beginning of the 1990s the Nokia design strategy stated that Nokia products should be identiable and global and should incorporate soft design language (Pulkkinen, 1997). Volvo was selected as the second case because the company had gone through a strategic renewal process from the early 1990s to the early 2000s, a remarkable process in which design played a key role. A number of articles and analyses in the automotive press paid attention to the consistent and meaningful relation between Volvos new design direction and the companys brand values and heritage. For example, the S80 model,

Data Sources

To meet the objectives of the study, data were collected from multiple sources between 2002 and 2004. The complete brand portfolios of cars and mobile phones were studied as expressions of strategic brand identity. Material on design concepts created by the companies was also collected and analyzed, as well as promotional material such as images of the products, press releases, annual reports, and Internet pages. An important objective was to understand why certain design decisions had been made on the visual design of the products and product portfolios. An initial conceptualization of the strategic approach chosen by the companies was developed after the collection of the secondary data already described. This conceptualization was then complemented and challenged in a number of in-depth interviews. Personal interviews were held with the designers and design managers of the companies to determine what was intended with the designs and, consequently, to achieve an additional level of interpretation. Three people were interviewed at Nokia (one of them, the design director, three times) and seven at Volvo (two of them, the design directors, twice). The interview duration varied between 30 minutes and 2 hours. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The interview schedule was adapted to the Nokia and Volvo cases and slightly modied from one interview to another to take the different positions and context of the interviewees into account. The topics that were covered dealt with the creation of

12

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

brand-specic design (e.g., What were Nokia- and Volvo-specic design features? How consistently were these features used over products in the portfolio?), the semantic transformation process (e.g., How did the work proceed from the verbal brief to the design elements? How free was a designer to use his or her creativity?), the design process (e.g., a description of the decisive points, the managers role in the process), and product examples.

Volvo to create visual brand recognition. A summary of these case descriptions is presented in the following section. Next, the key drivers behind the visual design strategies of both Nokia and Volvo are summarized, as well as the case-specic variation in these drivers. Finally, some implications for the design for visual recognition are discussed, referring to the themes identied in the introduction.

Data Analysis

The analysis of the products through images and 3D objects was conducted rst. This was done by identifying the design features companies were using across their product portfolios. The visual search was then supported by textual data from interviews and secondary sources. The analysis of this textual material involved a number of steps. The key thematic issues and their relations that emerged from the literature were conceptualized. Textual data, interview transcriptions, and other text material were then coded and organized on the basis of the conceptual framework. Data organization and coding were completed manually as a way of disaggregating the data, breaking it down into manageable segments, and identifying these segments (Schwandt, 1997). The practices of categorization (coding interviews into specied categories of phenomena), condensation (of the expressed meanings into shorter formulations), and ad hoc approaches (eclectic meaning creation with no standard method) were used in the data organization process (Kvale, 1996). Then, data were expanded, transformed, and reconceptualized through various iteration rounds to create more diversity in the analysis, which is especially important in descriptive studies (Coffey and Atkinson, 1996). Organization and interpretation of the data resulted in initial summaries of the Nokia and Volvo cases that were then sent to the designers and design managers of the companies for further comment. This allowed for a further test and validation of the analysis, and it enabled a deeper interpretation of the data. A comparison between the two cases resulted in the identication of a number of internal and external factors that serve as key drivers behind the different design philosophies of the two companies as well as differences in the way the companies set out to create visual brand recognition through design. Based on the analysis, a description was made of the strategic use of design references at Nokia and

Case Descriptions

During the latter part of the 1990s there was a signicant shift in the mobile phone industry from technology to design as the main area for differentiation. Nokia as market leader was at the forefront of this trend. The thematic focus of the Nokia case was on this development in the industry and on Nokias leading position in design from the late 1990s to the period of data collection in 20022004. Compared with the mobile phone industry, the car industry is relatively mature, and visual recognition has long been a strategic goal for most manufacturers. Design plays a fundamental role in the consumer assessment of cars and car brands. Volvo, in addition to being an established but relatively small brand on the global market, had given design a central competitive role along with a recently completed process of strategic renewal. The renewal, called Revolvolution, was initiated in the design of the Environmental Concept Car (ECC), presented at the Paris Motor Show in 1992, and was nally unveiled in the launch of the S80 model in 1998. Subsequent production models (V70, S60, XC90, S40 and V50, launched by the end of the data collection period) consistently followed the design philosophy that had been set by the ECC and S80. Based on a visual analysis of the brand portfolios, and, through the interviews and secondary source material, it was evident that both Nokia and Volvo used product design intensively, intentionally, and instrumentally to create and maintain the desired visual recognition for their brands. However, it also became clear that, during the time of the data collection, Nokia and Volvo had fundamentally different approaches to their design and portfolio strategies. The difference particularly concerned the degree of consistency within the product portfolio. As suggested in Figure 2, Volvo had adopted a consistent strategy in launching products, and its designs also contained a number of explicit brand references. Nokia, on the

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

13

brand references implicit explicit consistent product portfolio flexible NOKIA

VOLVO

Figure 2. Comparison of the Design Approaches Used by Volvo and Nokia

other hand, was managing the designs of the products in its portfolio more exibly and was also nurturing more implicit brand references in its products. It must be added that there was still some organization in the portfolio of Nokia. The company nurtured a variety of product lines, within which more consistent and explicit references were used. However, from the perspective of the total brand portfolio, the use of design was exible, and brand references seemed more implicit.

that Nokia had created, resulting from the customerdriven approach adopted by the company. The knowledge about customer segmentation that resided within the company formed a core capability. Nokia introduced specically designed products (and complete product lines) for different market segments well before its main competitors. Moreover, the company had gained a competitive advantage by way of its design excellence. Already in the mid 1990s, when the industry as a whole was still mainly technology driven, product design was considered a core strategic factor at Nokia. Nokias value-based approach to design became more important in the late 1990s, when a variety of line- and product-specic designs was introduced. The consistency of a product portfolio with varying designs was managed through subtle references, and some of these were even held to function at a subconscious level. Nokia designers claimed that their products, even those with very different designs, were recognized as Nokia products, because they incorporated specic design features in a more subtle, qualitative way.

The Nokia Design Philosophy

The key strategic intent of Nokia, as analyzed here, concerned the creation of personalized products for a wide range of market segments. As market leader, the company felt that every customer should nd an interesting and appealing product in its wide product family. However, for all phones usability was the number one priority; ease of use was regarded as a core Nokia value. These brand values also guided the design philosophy. Personalization and usability formed the core principles of Nokia design. Every new Nokia product was intended to incorporate characteristics such as comfort, balance, and pleasure of use. Nokia also wanted its phones to be perceived as friendly, developed on the basis of a human approach to technology. This was regularly mentioned in Nokias promotional material in the late 1990s and was considered important at a time when mobile phones were still regarded as a professional device for doing serious business. Making the products more approachable for a wider range of customers was a strategic goal for Nokia. Personalization was a design principle that led to a careful consideration of the design features (shapes, materials, colors, and details) that each product should have. The ability to create personalized products and take various user preferences into account was based on the effective market intelligence system

Nokia Design Features and Portfolio Flexibility

Until the early 2000s Nokia had nurtured a set of design features that were applied consistently over the product portfolio (Figure 3). The Y and U shapes were characteristic design themes, forming the typical Nokia silhouette and the curved frame around the display. The composition of the keypad and function buttons was an additional feature for which Nokia became known. The 3310, also due to its huge sales volumes, became the strongest representative of this design approach in Nokias history. Many of these design features (although executed differently and constantly evolving) are still apparent in recent Nokia models, and they still constitute a substantial part of Nokia brand recognition, as was noticed in a number of student workshops organized recently by one of the authors. At the time of the study, Nokia had radically expanded its product portfolio. The portfolio consisted of various product lines, each with its specic target segment and each with a different interpretation of Nokias general design philosophy. A basic phone (e.g., the 3310) had to differ visibly from a fashion phone and a premium phone. Nokias product portfolio as a whole had few consistently applied design features, and at the time of the study the versatility of the portfolio was increasing rapidly. The product

14

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

Figure 3. The Evolution of the Early Nokia Design Features in the Late 1990s

portfolio had expanded drastically, and many new product lines were emerging, based on Nokias intensive market segmentation effort. There were still many lead products that nurtured the classic Nokia design features, but new product lines with their own stylistic identity were introduced as well, both as high-volume models and models intended for niche markets. Despite the visual exibility over the entire product category, there were a number of recurring attributes across Nokia design. Usability was achieved by putting special emphasis on the development of a user interface that became standard in most Nokia phones. The functionality and layout of the keypad was also designed to increase usability, and it stayed recognizable over most product lines. There was also an attempt to maintain an impression of friendliness for all phones in the portfolio. Curved lines were preferred over straight lines. Although the U-shaped curve around the display (as with the 3310) was no longer standard, upward smiling curves were still used in most models for the lineup of keys in the keypad. The classical human-like Y shape silhouette was replaced in some models by other silhouettes, but these also stuck to curved, natural lines, which retained the value of high usability by tting comfortably in the hand. However, the U and Y shapes did not die out, and even to date some lead products in the portfolio show an evolutionary interpretation of these classical Nokia shapes.

closely connected to the strategic intent of Revolvolution, as well as Volvos core brand values and core capabilities. The intention of the strategic renewal was to shake up the Volvo brand image. The brand was losing customers, and a fresher appearance was needed to appeal to a younger clientele. However, it was important to preserve the strong heritage and brand recognition Volvo had achieved with earlier models. Volvo had become known as the number one safety brand in the automotive industry, based on its year-long emphasis and research and development (R&D) spending on safety. Moreover, the Scandinavian heritage was considered an inherent part of the Volvo brand, offering a vital basis for differentiating Volvo from its competitors. In addition to these established values of the Volvo brand, new values were introduced that underlined the renewal. A more dynamic approach was needed to give the brand a more emotive character and to lift it up to unambiguous premium status. The strategic intent, the core capabilities, and the new brand values were expressed in the Volvo design philosophy. As the most central Volvo value, safety was always put rst. The Scandinavian design approach was interpreted as a combination of functionality and simplicity with beauty and elegance. Furthermore, new Volvo design features had to provide the cars with a dynamic appearance that promised premium quality, which should lead to more affective recognition.

The Volvo Design Philosophy

In the design philosophy of Volvo the design of visual recognition for the brand was considered on a longterm basis. The new Volvo design philosophy was

Volvo Design Features and Portfolio Consistency

Within the new design philosophy, Volvo dened a number of explicit design features. These specic features included the characteristic front with the soft

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

15

Figure 4. Volvo Design Features Represented in the S60 Model

nose and the diagonal Volvo logo, the V-shaped bonnet, the strong shoulder line, the rear with its distinctively carved backlight, the third side window, and the owing line from roof to boot lid (Figure 4). The same features were used for all models introduced between 1998 and 2004, although the execution varied from model to model. The design philosophy that lies at the basis of these new models was guided by concerns for safety, Scandinavian design, and a more dynamic image for the brand. To start with the rst, Volvo wanted to create a stronger safety impression in the overall visual appearance of the car. The strong shoulders, for instance, made the sides look more solid and thicker, thereby appearing safer. Active safety showed most clearly in the interior design, specically in the control devices and instrument panel that reduced unnecessary information and potential distractions to the driver to a minimum. The clean, simple controls and instrument panel also accentuated the Scandinavian approach to design. A detail in the interior was the oating centre stack, the innovative instrument panel rst introduced in the S40 and then in all subsequent Volvo models. Top-range versions of this panel were made from Scandinavian oak and Volvo designers commonly described it as a piece of Scandinavian furniture. In addition, the exteriors new muscular look, its V-shaped bonnet, and the owing roof line created a strong impression of movement, and a number of other design features and details were carefully designed to enhance the emotional and premium appearance of the cars.

Volvos new design features were also explicitly promoted to the public to reinforce their recognition. The company aimed for complete attribution of the design features. The reason for this is that Volvo wanted not only to make its values recognizable for its target audience but also to help its target audience to be recognized by others as adhering to the Volvo values. Another aim of this communication was to show the relation between the new design philosophy and Volvos design heritage. The new design features of Volvo differed radically from the previous generation of Volvo cars. During the previous two decades Volvo had become known for its functional, robust, and static box design. Except for the grille and front lights, the new design features were not used during the box period. However, many of the new features, such as the V-shaped bonnet and strong shoulder line, referred back to historical Volvo models from before the box era (e.g., the famous PV 444/544 and P120 Amazon models from the 1940s and 1950s). Volvo made this link explicit in its promotions and releases to the automotive press. It was crucial for them that consumers would regard the new design, with softer edges and a dynamic appearance, as plausible for Volvo.

Key Drivers behind the Design Philosophies of Volvo and Nokia

When investigating why Nokia and Volvo chose their respective design philosophies, six principal drivers were derived from the data (Figure 5). These drivers

16

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

life-cycle stage

renewal cycle

brand position

portfolio width

brand heritage

product history

mature VOLVO consistent

long

niche small, well-defined target group

narrow

long, defined

solid, periodic styles

flexible NOKIA

growing

short

leader broad target group

wide

short, undefined

versatile, constant evolution

Figure 5. The Key Drivers behind Nokia and Volvo Strategies

are set to explain differences in the design philosophies between the two companies, based on which they had created visual brand recognition through the design of their products. Two external drivers were identied that relate to the product category (life-cycle stage and renewal cycle) and four internal drivers stemming from the companies past and present brand management strategies (brand position, portfolio width, brand heritage, and design history).

Life-Cycle Stage of Product Category

The product category in which the brand operates creates specic requirements for the management of a visual identity. In particular, the phase of the industry life cycle was found to affect the overall approach to design and the construction of the product portfolio. The growth of the mobile phone market was very high at the time of the study. As a consequence, more product lines and more phone models started to emerge, differing widely in visual appearance. The car market, in turn, was mature and contained models and product lines that faced direct competition from other companies. Car manufacturers and their brands had established positions in the marketplace. Competition was characteristically based on differentiation between the brands, based on the explicit and consistent use of design features.

fore, car design features had a long life span, while those for mobile phones followed short-term market trends. This meant that a consistent strategy was not a feasible option for Nokia and that design innovation was regarded as a core competence of the company. At the time of the study, mobile phone designs followed on from each other in quick succession. Each new model that came onto the market quickly made its predecessor appear outdated. Thus, Nokia was experiencing constant revolutions in design, as new innovative designs were introduced in different categories at an increasing pace. The whole mobile phone industry changed radically every few years. In contrast, Volvos approach to the design of new models was characterized by slow evolution. Design revolutions occurred rarely. There had been only ve major renewals in the 80-year history of Volvo cars.

Brand Position

The position of the company in the market affected its design philosophy. Nokia had reached the position of market leader and had been one of the key companies in establishing the mobile phone industry. World market domination was achieved during the end of the 1990s through a series of highly successful products. Nokia had also been one of the rst companies to develop new markets with the help of conspicuously distinctive products. As a dominant market player, Nokia was in a position to steer developments in the mobile phone market. This meant that Nokia was able to set new standards on the market and was more likely to take the lead in trying out new directions for mobile devices and their design features. The position of Volvo was that of a relatively small company in a mature and saturated market. Whereas Nokia covered

Renewal Cycle of Product Models

The life cycle of a single product was another driver that caused differences in the design philosophy. A typical Nokia model stayed on the market for 1 to 2 years, whereas a Volvo model was designed to last from 5 to 10 years (with minor modications). There-

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

17

a wide spectrum of mobile phone segments, Volvo was forced to nd a specic niche to gain a sufcient level of differentiation. As a result, the design philosophy of Nokia was more exibly and implicitly translated to design features, while that of Volvo could be applied more consistently and explicitly.

Width and Structure of the Product Portfolio

In general, the number of models on the market at a given time drives decisions regarding consistency. Consistency becomes untenable with many models in the portfolio (resulting, for instance, from serving many market segments), and a more exible application of a design philosophy is needed in this case. In the case of Nokia, some consistency was sought within different stylistic identities (represented, e.g., by the basic, classic, premium, and fashion product lines). These product lines had their own visual denition. For instance, the design of the Nokia 3310 was heavily inuenced by the requirements Nokia had dened for its basic line, in terms of visual appearance and the use of materials. However, the 3310 was a lead product for Nokia, and as such its design still had a strong impact on the visual recognition of the entire brand. For such lead products (usually mass-selling models), the design requirements for the product line were stringently applied, but Nokia allowed more experimentation in design for nonleading products. If the brand portfolio contains only a few models then the importance and signicance of a single product becomes much greater. In such a situation, every new model can have a great impact on brand recognition, and design decisions will have far-reaching implications for brand identity. This was the situation in the Volvo case. The messages that each new design carried were carefully considered, because every new car model was a considerable investment for the company and important in terms of brand identity and business success. For Volvo, each new model can be considered a lead product, and therefore, each model carried design features that it shared with other models in the portfolio.

such an important role. The company was established as early as 1865, but the Nokia brand remained virtually unknown outside Finland. The old Nokia had been a totally different company from the current Nokia. Its history restarted almost from scratch around 1990, following the companys structural change from a diverse business portfolio to a strong focus on telecommunication. Since that time Nokia had become one of the strongest brands in the world, and its core values were also widely recognized. New products had to be sufciently congruent with this recent heritage to avoid conicting messages. However, a strong sentiment existed at Nokia at the time of the study that it was making history for itself, and its experimentation with new designs may be seen as an expression of that. Volvo used its heritage intensively in its communications. The main values that were tied to its heritage were safety and its Scandinavian origin. The safety perception stemmed from the accumulated reputation that Volvo had gained through its history of technological and functional innovation in active and passive safety standards. The Scandinavian character was present on a more implicit level. It was not easy to indicate precisely which elements in the history of Volvos design made the brand characteristically Scandinavian. Still, in the design philosophy both values were listed as departure points for new designs.

Product History

For both Nokia and Volvo, past models inuenced current design features. However, there was a difference in the explicitness and singularity in the way the companies product histories were treated in the current design philosophies. Nokia had a short product history due to the young age of the mobile phone industry. Furthermore, Nokia carried several product lines, each with its own stylistic identity and own history. This made it difcult to show a clear path of historical examples. However, the design features used in the very early Nokia products, even if for a short time and for very small markets, were still regarded as Nokia cues. These features were not neglected in the current portfolio. The new Volvo design approach made explicit references to past models. This was important because the strategic renewal of Volvo implied a major change in design compared with the previous Volvo generation. This required the company to communicate that

Brand Heritage

The prevailing image and reputation of the brand on the market affects the formation of recognition. As already noted, this situation is typical for companies in mature industries. A strong heritage and early-established identity form an effective basis for brand recognition. At Nokia, brand heritage did not play

18

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

the new design philosophy was connected to Volvo designs from a more distant past. Overall, past products have a decisive inuence on product design for a surprisingly long time. One of the greatest challenges for design is to nd the right balance between familiarity and novelty. Companies seek the familiar in their own product history, starting from the very rst product of the brand. It is felt that references in the design to past products can have a considerable impact on the future recognition of the brand. Thus, if new companies establish their brand by accident rather than by design, they may have to reinvent or clean up the brand later on (Cagan and Vogel, 2002).

Strategic Design for Visual Recognition

The case-specic variation in how the drivers exert their inuence indicates that the requirements for designing visual recognition are industry-, product- and company-dependent. Therefore, the generic strategic guidelines that are given here should be regarded as sensitizing issues for further research and for practitioners who may consider them against the background of their experience, expertise, and knowledge of portfolio management and strategic product design.

Semantic Transformation

Once a strategic approach has been chosen regarding the use of design features in the portfolio, the major issue becomes how these features should represent the core brand values. Nokia and Volvo had dened a set of core values that functioned as a basis for the development of their design features. As the case descriptions illustrate, both Nokia and Volvo had used design features that made sense given the brand values of the company. For instance, specic curves of

Nokia phones may be interpreted as a friendly smile, which supports the brand values of personalization and a human approach. Volvos shoulder feature, in turn, refers to the value of safety by its intended interpretation as solid and protective (Figure 6). Of course, both companies ensured that the key design features of products evoked the desired associations among target users. Knowledge concerning different user groups, as well as social and cultural contexts of interpretation, is another prerequisite for effective design. User tests and customer clinics are the means through which this kind of knowledge can be created, as practiced by both Nokia and Volvo. In the Nokia and Volvo cases, designers used features to represent the brand values of safety, dynamism, and personalization, and these were intended to be understood by most consumers in the same way, leading to complete attribution. Volvo used a consistent set of design features over its portfolio, and it considered all its models lead products, in the sense of being the best example for the brand at the moment of market introduction. Nokia, on the other hand, designed models for various product lines that each had its own stylistic identity and a continuous ow of new models. As a consequence, the explicit references in its products tended to have partial attribution, because they were tied to a specic market segment, and their aim was to differentiate the product within the brand, against Nokia phones in other product lines. In trying to maintain recognition for the overall Nokia brand the models also carried more implicit references to differentiate the brand from other mobile phone brands, so these had to have complete attribution. Thus, all Nokia phones, even those from highly distinct product lines, still shared some features that would be recognized by most people as expressive of Nokia values. Taking the two cases together, a tentative conclusion is that lead products and nonlead products (as variations of the lead products) can be dened

Volvo shoulder

interpreted as solid

R

Nokia curve

interpreted as friendly smile

O

safety

personalization, human approach

Figure 6. The ROI Framework Applied to Volvo and Nokia Cases

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

19

brand references explicit implicit Variations of lead products for betweenbrand differentiation

complete

Lead products (between-brand differentiation)

attribution Variations of lead products for within-brand differentiation

partial

Figure 7. A Tentative Design Strategy for Lead Products and Their Variations

by the type of brand reference that is made and the type of attribution that takes place (Figure 7). Lead products serve to differentiate the brand from other brands in the market. As a result, they will have explicit references with complete attribution. Later variations of these lead products will consist of a mix of explicit references with partial attribution (serving further differentiation within the brand) and additional, more implicit references with complete attribution (serving between-brand differentiation).

Visual Consistency of Product Portfolios

A number of guidelines for strategic decisions concerning the visual consistency of the brand portfolio can be derived from the key drivers. If the brand operates in a mature product category, characterized by established solutions for the technology-user interface and a stable brand image, greater consistency over the portfolio may be preferred. Consistency in the portfolio may also be benecial when the renewal cycle of products and product lines is long. In addition, the consistent use of explicit design features over the portfolio is likely to be more appropriate for niche brands (and possibly also for new brands) that focus on a limited number of market segments. If the brand has a strong heritage and, in particular, if the brand has already nurtured a recognizable design identity throughout earlier product generations, there may be a greater need for consistency in the brand portfolio and also a greater potential to create consistency by referring to iconic designs from the brands past. On a more general level there may exist two divergent strategies with respect to the maintenance of

visual recognition of products in a brand portfolio. Companies can aim to build coherent product portfolios where each product has a number of explicit design features, or they can create individual identities for different products in the portfolio. In the latter case, brand recognition is managed by the creation of lead products in separate product lines that each have their own stylistic identity and their own explicit design features. Each lead product then represents a variation of what the brand stands for, and it is through this variation that the brand identity is dened. As stated before, the repeated use of design features over different models can enhance their recognition. Customers have to learn the design features to be able to identify new products as belonging to a certain brand and expressing its values, and repeated exposure to the design features is critical in this. But repetition can also incite boredom and reduced attention for the brand values that are expressed through its design. Therefore, managing the equation of renewal and consistency in employing design features may be crucial for sustaining the visual recognition of the brand. This implies that there is also a need for outof-the-box thinking and innovative concept creation through which the freshness and topicality of the visual appearance is ensured. The Volvo concept cars highlighted such thinking. Besides being consistent in visual appearance by incorporating the Volvo design features, they explored the possibilities for renewal and further development of the visual identity of Volvo through a number of concept studies. In the car industry, concept studies represent an established practice of presenting design innovations and preparing the public for changes in the future. As such they are crucial instruments for brand management (Karjalainen, 2006).

Managing Strategic Renewal and the NPD Process

The unity of intent and consistency of action are thought to be starting points for the successful management of design (Ravasi and Lojacono, 2005). The specic challenge within NPD is to maintain these qualities in a design process that has many parties inuencing decisions on the visual appearance of products. If the core brand values are understood, agreed upon and internalized by all involved parties, it becomes easier to employ design for the creation of visual brand recognition. At Nokia, design managers played an important part in this since they were required to translate the general brand values of the

20

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

company to a design philosophy with many adaptations for the various market segments it served. They also had to promote this philosophy to all parties involved and to organize the implementation of this philosophy into actual product designs. In the Volvo case, where the market was more uniform, the process was less formalized. Here the current director of design acted as the main catalyst in the renewal of Volvos design philosophy, pushing it away from what the company was used to. By paying special attention to lead products, concept studies, and iconic designs from the brands past, the design manager created anchor points that best expressed the core brand values and that inspired all parties involved in the NPD process. Stories similar to the Volvo case can be found in other companies such as BMW (Bangle, 2001). Finally, what characterized both the Nokia and Volvo cases was the central role that design had been given in the company strategy. Design was not merely regarded as answering to the requirements of other functions. Instead, designers themselves contributed to the design philosophy through the design features they created. In this sense, a design philosophy is always a project under construction and never a closed booklet with a set of examples of design features that designers can copy and paste. As already suggested by Ravasi and Lojacono (2005), it is important that design is acknowledged as a driving force in itself, contributing to strategic renewal of the brand and corporation, driving brand repositioning and inspiring strategy formulation.

Conclusion

This paper presents two cases of companies that have strategically employed design to create visual recognition for their brand values. In both cases it was found that companies took a deliberate and planned effort to translate the core brand values of the company to a design philosophy. This philosophy specied a number of design principles and design features to be used in the design of the companys products. Both companies were found to express their core brand values through design features, based on a process of semantic transformation. Control over this process enabled managers in both companies to make strategic decisions over the type (genuine, stringed), strength (explicit, implicit), and generality (complete, partial) of the relation between design features and brand values.

The inuence of the design philosophy over the design of products was found to vary over the companys product portfolio. The inuence was most complete for the companys lead products, which incorporated the design features specied in the philosophy to the fullest and thus served as reference points for what the brand stands for. The design of these lead products received most attention from design managers, and they served as examples for later NPD projects in the company. In this way, the inuence of the design philosophy was felt throughout the companys product portfolio. A between-company analysis of design and brand portfolio management led to the identication of a number of factors that drive a companys strategy for establishing visual recognition for the brand. The existence of these drivers implies that there is no simple recipe for creating visual recognition of the brand. Instead, the design effort of the two companies for the creation of visual recognition was based on a continuous renewal of the connection between brand value and design features. This renewal can sometimes be revolutionary and highly consistent and sometimes evolutionary and multifaceted, depending on the type of company and the market it is serving. The insights resulting from this analysis can be used as a basis for further research on the strategic role that design can play in innovation processes and NPD. New studies could, for instance, look at companies that do not have such a strong focus on design as a strategic instrument as Nokia and Volvo. Both companies originate from the Nordic countries, where a strong focus of design in industry has a long and established tradition. Thus, it would be good to consider cases from other regions where a company focus on design has been lacking or where the role of design in industry has a different tradition. Additional studies could also delve more deeply into the precise nature of some of the drivers of design philosophies discussed here. For example, the driver brand position describes the relative size of the company in the market, which has implications for its leadership in setting market standards but also for its organizational complexity. These two aspects of brand position could not be disentangled in the present study: Compared with Volvo, Nokia was more of a standard setter as well as a more complex organization. As a result, the effect of these two factors on the design philosophies of the companies could be described only in combination under the more abstract notion of brand position. The drivers may also be interrelated. For example, the im-

DESIGNING VISUAL RECOGNITION

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

21

portance of brand heritage seemed typical for companies in mature industries. A better understanding of such relations may lead to a prioritized and more structured view of the drivers of design philosophies. Given the limited number of cases in this study, these issues have not been addressed here. The focus in this study on the company intended effects of design on visual recognition has led to three limitations. First, this study has looked at the intentions of companies to create visual recognition, whereas, ultimately, recognition of the brand is created in the market. The focus in this study has been on the company, and the assumption has been that the companies had extensive market data on the basis of which they formulated their design philosophies. However, it would be interesting to further explore the relation between the symbolic meanings that companies bestow on their products through design, and the meaning that the market attributes to products, based on the same design. Second, the study looked only at the visual qualities of design and by doing so disregarded the other senses. The visual may be dominant in customer recognition, but information from the other senses (e.g., auditory, tactile, olfactory) may also play an important role. For example, the attention Nokia paid to its characteristic ring tone led it to produce one of the rst friendly, nontechnical-sounding ring tones, and as such it is a good example of Nokias human approach to technology. This suggests that semantic transformation of brand values into design features into brand values might be extended to other modes of perception. Third, the intended communication of brand value through design has been studied only with the goal of recognition in mind. Other goals for design, such as exploration of and reliance on the product (Krippendorff, 2005) have been left aside. For example, BMWs position as the ultimate driving machine is underscored by its cars, whose road-handling qualities can be explored extensively. Such exploration of the product can be another goal of design through which brand values can be communicated. A complication arises here, because it becomes difcult to disentangle the symbolic qualities of design (that communicate brand value) from the functional qualities (that deliver the benets related to the brand value). However, for exactly that reason the communicative role of design at the stages of exploration and reliance is worth further investigation. It should be noted that these conclusions run somewhat counter to the idea of design DNA that prac-

titioners in many companies are talking about. The analogy with DNA suggests that the visual identity of companies and their brands is inherited and develops as a matter of course, and it implies that change in the visual identity comes slowly and over many generations. The relationship between design and brand identity that has been found here is one that can be planned, has to be internalized, and is open to radical change. The notion of design DNA may also point to design as an inner strength of the company that keeps it t for the market. It was found that design can sometimes be such a driver, but it is also driven itself by a host of internal and external factors. It is thus recommended that design becomes a less primal and more self-reective strategic force in a company, working together with corporate, technological, and commercial strategic forces.

References

Aaker, D.A. (1996). Building Strong Brands. New York: Free Press. Ainamo, A. and Pantzar, M. (2000). Design for the Information Society: What Can We Learn from the Nokia Experience. Design Journal 3(2):1526. Bangle, C. (2001). The Ultimate Creativity Machine: How BMW Turns Art into Prot. Harvard Business Review 79(1):4755. Barsalou, L.W. (1999). Perceptual Symbol Systems. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 22(4):577609. Biederman, I. (1987). Recognition-by-Components: A Theory of Human Image Understanding. Psychological Review 94(2):11547. Biederman, I. and Ju, G. (1988). Surface versus Edge-Based Determinants of Visual Recognition. Cognitive Psychology 20:3864. Borja de Mozota, B. (2004). Design Management: Using Design to Build Brand Value. New York: Allworth Press. Cagan, J. and Vogel, C.M. (2002). Creating Breakthrough Products: Innovation from Product Planning to Program Approval. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Coffey, A. and Atkinson, P. (1996). Making Sense of Qualitative Data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Crilly, N. (2005). Product Aesthetics: Representing Designer Intent and Consumer Response. Ph.D. diss., Cambridge University, Cambridge, UK. Du Plessis, E. (1994). Recognition versus Recall. Journal of Advertising Research 34(3):7591. Ealey, L. and Troyano, L. (1997). Cars as Commodities. Automotive Industries 177(3):7781 (March). Finn, A. (1988). Print Ad Recognition Readership Scores: an Information Processing Perspective. Journal of Marketing Research 25:16877. Giard, J. (1990). Product Semantics and CommunicationMatching the Meaning to the Signal. In: Semantic Visions in Design, ed. S. Vihma. Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki, b1b7. Harkins, J., Coleman, O.W., and Thomas, G. (1998). Commentaries on the State of the Art in Consulting. Design Management Journal 9(3):3540. Harris, F. and de Chernatony, L. (2001). Corporate Branding and Corporate Brand Performance. European Journal of Marketing 35(34):44156.

22

J PROD INNOV MANAG 2010;27:622

T.-M. KARJALAINEN AND D. SNELDERS

Janlert, L.-E. and Stolterman, E. (1997). The Character of Things. Design Studies 18(3):297314. Kapferer, J.N. (1992). Strategic Brand Management: New Approaches to Creating and Evaluating Brand Equity. New York: Free Press. Karjalainen, T.-M. (2004). Semantic Transformation in DesignCommunicating Strategic Brand Identity through Product Design References. Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki. Karjalainen, T.-M. (2006). Strategic Concepts in the Automotive Industry. In: Product Concept DesignA Review of the Conceptual Design of Products in Industry, ed. T. Keinonen, and R. Takala. New York: Springer Verlag, 13355. Kotler, P. and Rath, G.A. (1984). Design: a Powerful but Neglected Strategic Tool. Journal of Business Strategy 5(2):1621. Kreuzbauer, R. and Malter, A.J. (2005). Embodied Cognition and New Product Design: Changing Product Form to Inuence Brand Categorization. Journal of Product Innovation Management 22:16576. Krippendorff, K. (1989). On the Essential Contexts of Artifacts or on the Proposition that Design Is Making Sense (of Things). Design Issues 5(2):939. Krippendorff, K. (2005). The Semantic Turn: A New Foundation for Design. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Kvale, S. (1996). InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Louro, M.J. and Cunha, P.V. (2001). Brand Management Paradigms. Journal of Marketing Management 17(78):84975. Mono, R. (1997). Design for Product Understanding: The Aesthetics of Design from a Semiotic Approach. Stockholm: Liber. Mooy, S.C. and Robben, H.S.J. (2002). Managing Consumers Product Evaluations through Direct Product Experience. Journal of Product & Brand Management 11(7):43246. Muller, W. (2001). Order and Meaning in Design. Utrecht: Lemma Publishers. Olson, E.M., Cooper, R., and Slater, S.F. (1998). Design Strategy and Competitive Advantage. Business Horizons 41(2):5561. Oppenheimer, A. (2005). Products Talking to PeopleConversation Closes the Gap between Products and Consumers. Journal of Product Innovation Management 22:8291. Peirce, C.S. (selected and edited with an introduction by J. Buchler) (1955). Philosophical Writings of Peirce. New York: Dover Publications.

Peirce Edition Project (Ed.) (1998). The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings, Volume 2 (18931913). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Pulkkinen, M. (1997). The Breakthrough of Nokia Mobile Phones. Helsinki: Helsinki School of Economics and Business Administration. Rakover, S.S. and Cahlon, B. (2001). Face Recognition: Cognitive and Computational Processes. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Ravasi, D. and Lojacono, G. (2005). Managing Design and Designers for Strategic Renewal. Long Range Planning 38:5177. Schmitt, B. and Simonson, A. (1997). Marketing Aesthetics: The Strategic Management of Brands, Identity and Image. New York: Free Press. Schwandt, T.A. (1997). Qualitative Inquiry: A Dictionary of Terms. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Singh, S.N., Rothschild, M.L., and Churchill, G.A. Jr. (1988). Recognition versus Recall as Measures of Television Commercial Forgetting. Journal of Marketing Research 25:7280. Silverman, D. (2000). Doing Qualitative Research. London: Sage Publications. Simon, H.A. (2001). The Sciences of the Articial, (3d ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Smets, G.J.F. and Overbeeke, C.J. (1995). Expressing Tastes in Packages. Design Studies 16:34965. Steffen, D. (2000). Design als Produktsprache Der Offenbacher Ansatz in Theorie und Praxis. Frankfurt (Main): Verlag Form. Stompff, G. (2003). The Forgotten Bond: Brand Identity and Product Design. Design Management Journal 14(1):2632. Vihma, S. (1995). Products as Representations. Helsinki: University of Art and Design Helsinki. Volvo Press Release (1999). March 9: Volvo Wins European Automotive Design Award. Goteborg: Volvo Car Corporation. Warell, A. (2001). Design Syntactics: A Functional Approach to Visual Product Form. Gothenburg: Chalmers University of Technology. Wickstrom, L. (2002). Produktens budskapMetoder fo vardeing r av produktens semantiska funktioner ur ett anva ndarperspektiv. Gothenburg: Chalmers University of Technology. Zaltman, G. (1997). Rethinking Marketing Research: Putting People Back In. Journal of Marketing Research 24(4):42437.

This document is a scanned copy of a printed document. No warranty is given about the accuracy of the copy. Users should refer to the original published version of the material.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Design Management: Using Design to Build Brand Value and Corporate InnovationVon EverandDesign Management: Using Design to Build Brand Value and Corporate InnovationBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (4)

- Brand Logo and Its ImportanceDokument64 SeitenBrand Logo and Its ImportanceDeepak SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand ArticleDokument20 SeitenBrand ArticleAbdur RahmanNoch keine Bewertungen