Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kenneth M Gold - School's in (Book Review - History of Education Quarterly - Srping 2003)

Hochgeladen von

Tina BrunoOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kenneth M Gold - School's in (Book Review - History of Education Quarterly - Srping 2003)

Hochgeladen von

Tina BrunoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

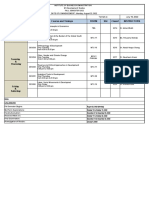

I Book Review History of Education Quarterly, 43.

11 The History Cooperative

Page 1 of 3

Vol. 43, No.

Spring 2003 Previous

Journals

Search

Partners

Information

Next

Table of contents

Table of contents

Search Builder

Book Reviews

List journal issues Home Printer-friendly format

Kenneth M. Gold. School's In: The History of Summer Education in American Public Schools. New York: Peter Lang, 2002. 315 pp. Paper $29.95. Kenneth Gold in no way makes so bold a claim as to say that one cannot fully understand the institutional development of public schooling in this country without understanding the changing historical role of public summer education. However, reading School's In, one could well think such a bold claim would not have been entirely out of line. Gold's serious, well researched, and well documented scholarly work on the changing nature of summer education in United States public schools presents a number of findings that revise and deepen our understanding of how public schooling developed institutionally. Gold sweeps away the enduring myth that schools in America have traditionally been closed during the summer because children's labor was needed on the family farm. Not only does this myth make no sense for urban school calendars but it also ignores the reality that farm life is most intense during spring and fall (at planting and harvest time), when rural schools did typically close. Similarly, Gold revisits the enduring perception that summer schooling has never been of equal caliber as schooling at other times of the year. Looking at records from New York, Michigan, and Virginia, he finds that rural and urban schools generally enrolled about as many students, taught the same types of subjects, and hired about as many teachers during the summer and winter terms. During summer terms in rural areas, however, young girls were more often hired to teach than during winter terms. Based on these findingsthat summer terms were an integral part of urban and rural schools from early to mid nineteenth centuryGold asks what happened to them. Why were summer terms eliminated? The answer Gold offers differs for rural and urban areas. In rural areas, he argues, they became a "casualty of efforts to lengthen and standardize school terms" (p. 19), while in urban areas they disappeared because of: the emerging middleclass habit of taking summer vacations; school budgetary crises; and school officials' beliefs: (1) that "school conditions in the summer were inferior, despite the availability of statistics that contradicted this view" (p. 72), (2) teachers could develop professionally during the summer, and (3) students and teachers needed rest lest they be overtaxed. Gold's most interesting chapter is the third ("'School's Out for Summer': Ideology and the Creation of Summer Vacation, 1840-90"), which provides a plausible (and convincing) explanation for how, in the absence of any centralized national authority or coordinating agency, school calendars

http://wvvw.historycooperative.org/journals/heq/43.1/br 8.html

5/26/2004

I Book Review I History of Education Quarterly, 43.1 I The History Cooperative

Page 2 of 3

Published by The liistory of Education Society

coalesced across the countryin both rural and urban areas, regardless of regionwith summer as a time for vacation. This chapter's explanation rests on a rhetorical and sociological analysis showing how conventional nineteenth-century understandings of how the mind worked and of time had opposite effects upon rural and urban school systems as they underwent calendar reforms. In urban areas where the school year was long (ranging from 240 to 259 days in major cities in the 1840s) these understandings made it logical to reduce the length of the school year to around 200 days by the century's end so as not to overtax students' and teachers' mental capacities. In rural areas, where the school year was often irregular, these understandings made it logical to increase the length of the school year to reduce students' "setback," i.e., the loss of learning and mental agility that can occur over long vacations. For most readers, these first three chapters may be the most interesting half of Gold's book because they provide an innovative slice through familiar (and some unfamiliar) territory. The next three chapters are more conventional. They explain why the school year became shorter over the end of the nineteenth century; how nonacademic summer "vacation schools" emerged in cities around the turn of the century to fill the lengthening summer break; and how vacation schools became transformed into academic summer school in the early twentieth century. Gold provides detailed case studies with abundant statistical evidence of the development of vacation schools in Providence and Newark and of the institutionalization of academic summer school in Detroit. He identifies four distinct stages in the development of vacation schools and their transition into summer schools: (1) vacation schools were founded by charitable organizations, (2) vacation schools were partially public funded, (3) vacation schools were completely public funded, and (4) academic classes for credit were introduced into vacation schools and eventually took over the summer curriculum, turning the schools into extensions of the regular public school or into "summer schools". Gold's analysis reveals that while vacation schools largely served their target populationimmigrant and lower-class students, for whom they actually served as a form of summer day care when they became summer schools, the student body changed in ways not anticipated by school officials: the summer schools became filled with students seeking or pushed to skip ahead. When summer school became largely a means of getting "students through the graded system"(p. 204), summer schools came under harsh criticism: "administrators judged them by the standards of the regular schools, ... [and] deemed them insufficient: they admitted too many marginal students, they promoted students too easily, and they lacked enough time to cover a school subject fully" (p. 208). These criticisms, Gold concludes, were most likely well-founded. However, Gold contextualizes such concerns about summer school by pointing out the role administrators and educators played in relegating summer school to a subordinate place in the public school system: "Educators set up a system in which credentialism mattered as much as learning and then complained when students blatantly used summer school to obtain such credentials and summer staffs lowered learning standards for them" (p. 206). Gold concludes the book with an epilogue that tells the story of summer

http://www.historycoopemtive.org/journals/heq/43.1/br 8.html

5/26/2004

IBook Review I History of Education Quarterly, 43.1IThe History Cooperative

Page 3 of 3

Published by The History of -Education Society

school after it became institutionalized as an extension of the regular public school. The epilogue traces how the federal government incorporated summer school into the National Defense Education Act of 1958, compensatory education programs in the 1960s and 1970s, and education excellence in the 1980s and 1990s. In doing so, he contends, the federal government encountered the same problems that run throughout the history of summer education. Gold ends by drawing out the policy implications of using summer education and recommending that "summer can and should play a vital and special role in public education today" (p. ?). This is a fine study that is accessible, well organized, and draws broadly 9 from multiple case studies across the country. It can be criticized for not drawing enough on western sources, for not bringing out the experience of summer school or its content at different historical moments, and in a few points for seeing a little too much through the lens of summer education. For example, the claim that "Innovations like consolidated districts, free schools, graded classes, and an official school year were all designed in part to increase the length of the school year and to decrease the use of summer for schooling" (p. 27) seems to stress a "part" that was a very minor if at all part of the original purpose of making schools free and instituting graded classes. However, such criticism would miss one of the main contributions of this work: it tills new ground and provides a broader historical foundation for the emerging wave of scholarship that seeks not to criticize or place blame for problems with the institutional development of public schooling, but rather, to explain the development in a way that adequately accounts for the same institutional changes occurring across the country, in historical proximity, under very different political and social conditions

Stephen Provasnik American Institutes for Research

Presented online In association with the Ilistory Cooperative

The History of

Education Society

0 2003

Content in the History Cooperative database is intended for personal, noncommercial use only. You may not reproduce, publish, distribute, transmit, participate in the transfer or sale of, modify, create derivative works from, display, or in any way exploit the History Cooperative database in whole or in part without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Spring 2003

Previous

Table of contents

Next

http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/heq/43.1/br 8.html

5/26/2004

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Status and Role: L S C ADokument2 SeitenStatus and Role: L S C ADeryl GalveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bar Matter 1645Dokument2 SeitenBar Matter 1645Miley LangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Virginia Saldanha-Bishop Fathers Child by NunDokument17 SeitenVirginia Saldanha-Bishop Fathers Child by NunFrancis LoboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Program On 1staugustDokument3 SeitenProgram On 1staugustDebaditya SanyalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay On Rabbit Proof FenceDokument6 SeitenEssay On Rabbit Proof Fencepaijcfnbf100% (2)

- Education AutobiographyDokument7 SeitenEducation Autobiographyapi-340436002Noch keine Bewertungen

- I. Heijnen - Session 14Dokument9 SeitenI. Heijnen - Session 14Mădălina DumitrescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malolos Constitution Gr.6Dokument8 SeitenMalolos Constitution Gr.6jerwin sularteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 Discussion QuestionsDokument4 SeitenChapter 1 Discussion Questionslexyjay1980Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nationalism and Globalization Are Two Concepts That Have Been Debated For CenturiesDokument2 SeitenNationalism and Globalization Are Two Concepts That Have Been Debated For Centuriesjohn karloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motions Cheat Sheet Senior MUNDokument2 SeitenMotions Cheat Sheet Senior MUNEfeGündönerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kansas Bill 180 SenateDokument2 SeitenKansas Bill 180 SenateVerónica SilveriNoch keine Bewertungen

- 140-French Oil Mills Machinery Co., Inc. vs. CA 295 Scra 462 (1998)Dokument3 Seiten140-French Oil Mills Machinery Co., Inc. vs. CA 295 Scra 462 (1998)Jopan SJNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction To ASEANDokument15 SeitenAn Introduction To ASEANAnil ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alt-Porn and (Anti) Feminist Identity - An Analysis of Furry GirlDokument34 SeitenAlt-Porn and (Anti) Feminist Identity - An Analysis of Furry Girljessica_hale8588Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Dokument5 SeitenMankin v. United States Ex Rel. Ludowici-Celadon Co., 215 U.S. 533 (1910)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Countries AND NATIONALITIESDokument2 SeitenCountries AND NATIONALITIESSimina BusuiocNoch keine Bewertungen

- 365 Islamic Stories For Kids Part1Dokument173 Seiten365 Islamic Stories For Kids Part1E-IQRA.INFO100% (14)

- World Watch List 2010, Open DoorsDokument16 SeitenWorld Watch List 2010, Open DoorsOpen DoorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Federalism in India: A Unique Model of Shared PowersDokument12 SeitenFederalism in India: A Unique Model of Shared PowersAman pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- JSAC Profile2014Dokument12 SeitenJSAC Profile2014marycuttleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Site Selection: Pond ConstructionDokument12 SeitenSite Selection: Pond Constructionshuvatheduva123123123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Command History 1968 Volume IIDokument560 SeitenCommand History 1968 Volume IIRobert ValeNoch keine Bewertungen

- MS Development Studies Fall 2022Dokument1 SeiteMS Development Studies Fall 2022Kabeer QureshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageDokument5 SeitenSahitya Akademi Award Tamil LanguageshobanaaaradhanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- الأسرة الجزائرية والتغير الاجتماعيDokument15 Seitenالأسرة الجزائرية والتغير الاجتماعيchaib fatimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Council of Red Men Vs Veteran ArmyDokument2 SeitenCouncil of Red Men Vs Veteran ArmyCarmel LouiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multiculturalism Pros and ConsDokument2 SeitenMulticulturalism Pros and ConsInês CastanheiraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"Dokument4 SeitenRhetorical Analysis of Sotomayor's "A Latina Judges Voice"NintengoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Career: Carlo AngelesDokument3 SeitenProfessional Career: Carlo AngelesJamie Rose AragonesNoch keine Bewertungen