Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Intro To Communitarianism - Butcher

Hochgeladen von

PRMurphyOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Intro To Communitarianism - Butcher

Hochgeladen von

PRMurphyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

COMMUNITARIAN VALUES as AMERICAN LUXURIES *

There are different ways to view the effort to build community. One view, that our only choices are chaos or community, suggests that building intentional community is a necessity in order to assure our long-term survival. A less fatalistic view is that building community, of any kind, is the effort to create luxuries that can not otherwise be enjoyed. These luxuries can also be called communitarian values. As fifty years of the post-war housing industry has shown, communitarian values are luxuries that we do not absolutely need if all that we are trying to do is acquire housing. Today, however, the challenge is to build a social fabric that provides, in addition to mere shelter, a culture that engenders in the individual an appreciation of others and a sense of responsibility for the environment we share. Communitarian values focus upon providing a safe and nurturing environment for children and seniors, community food service, and other collective services, such as building and auto maintenance, where people work together for mutual advantage and efficient resource usage. Communitarian values are experienced in neighborhood forums where people resolve disputes or discuss opportunities or challenges from within or from outside of the community. Communitarian values are supported by architectural and land use designs that encourage the random kindnesses and senseless acts of beauty that encourage interactions among people, and the development of friendships and other primary and secondary social bonds. As the effort to build community must seek to counter the generations of acculturation to the paradigm of home as moated castle, a new paradigm may be created in order to replace the materialistic American Dream and the paternalistic domestic mystique, with a more transcendent American Dream focused upon the egalitarian community mystique. Presenting communitarian values as a set of luxuries that money alone can not buy can serve this end. Consider the priceless value of the peace of mind that comes with knowing on a first name basis everyone in your neighborhood, because you talk and work with them regularly in day-to-day living. This we might call the trust luxury. The informal ambience of the common spaces, serving to facilitate interactions among people, we might call a social luxury. Consider too how the fellowship of community respects the spiritual ideals of brother- and of sisterhood, of living by the Golden Rule, or of practicing a love-thy-neighbor ethic. The opportunity to conform our lifestyle to our spiritual ideals can be cast as a spirituallycorrect luxury, while the focus upon sharing and ecological design is presented as a politically-correct luxury. And more than mere luxury, intergenerational community where both young and old are encouraged to care for the other, in comparison with the usual pattern of age segregation in America, is cultural elegance. Visiting other communities around the world is a holiday luxury. All of these and more are communitarian luxuries available to everyone.

A PHILOSOPHY OF HAPPINESS

In the pursuit of happiness, many people realize that good health, a personal outlook of optimism, personal control over ones own life, physical activity, and the quality of relationships we enjoy are all more important than personal wealth alone.* Through interweaving our concerns, cares, sadnesses, joys and loves with those of others, all of the elements of happiness, including health, optimism, control, activity and relationships, can be concentrated into a mutually supportive dynamic. Communitarianism then becomes a philosophy of happiness as the individual realizes that the well being of others is important to the securing of their own personal happiness. ** This introduction to communitarianism presents ways of understanding how people have collectively expressed and are living various philosophies of happiness. All communitarian designs share basic values of mutual aid, sharing and cooperation, yet their methods run the full spectrum of social and cultural designs. This brochure offers a set of definitions of terms and a classification structure for various intentional community designs. * John Stossel, Happiness in America, ABC, 20-20,

April, 1996. See also: Amitai Etzioni, The Spirit of Community: The Reinvention of American Society, Touchstone, 1993. The Communitarian Network, 2130 H St. NW, Ste. 714, Wash. DC 20052, (202) 994-7997.

A. Allen Butcher, March, 1998 For more detail on these concepts, see: Classifications of Communitarianism, Fourth World Services, PO Box 1666, Denver, CO 80201, 303-355-4501.

COPY and DISTRIBUTE FREELY

Introduction to

Communitarianism

Cohousing, Ecovillages, Communal Societies and other Intentional Community Designs

** See: Abraham Maslow, Toward a Psychology of

Being, Van Nostrand, 1968, and, Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, 1790, as quoted by Francis Moore Lappe in Self and Society, Creation, March/April 1988.

* Edited from, CoHousing as an American Luxury, by A. Allen Butcher printed in CoHousing, Summer, 1996.

THE ROLE of COMMUNITY in CONTEMPORARY CULTURE

As many intentional communities are created in response to problems perceived in the larger culture, these may be seen as small-scale, experimental societies, developing innovations in architecture and land use, governmental structures, family and relationships, and other aspects of culture that may provide viable alternatives to our global, monolithic, consumerist society. As crucibles-of-culture, intentional communities tend to attract many of the new and hopeful ideas of the day, develop them in living, small-scale societies into useful innovations, and then model successful adaptations of these ideas to the outside world. Although some intentional communities become very doctrinaire, closed societies, frozen in time like many Catholic monasteries and Hutterite colonies, others are open, encouraging an ongoing exchange with the larger culture. Open communities like cohousing, ecovillages and egalitarian societies provide insights into the direction of the larger society through their successful cultural innovations. In this way, intentional community serves to anticipate, reflect and quicken social change.

The COMMUNITARIAN CONTINUUM

Describing different communities according to their degree of common awareness and of collective action. INTENTIONAL COMMUNITY Substantial common agreements and collective actions: Zealotry Self-sufficiency Separatism Diversity among communities BALANCE or MODERATION within a community between separatism from and integration with the larger culture. May be either an intentional or a circumstantial community. CIRCUMSTANTIAL COMMUNITY Minimum of common agreements and of collective actions: Apathy Homogeneity Integration Uniformity of communities.

SHARING--to-PRIVACY CONTINUUM

When considering what kind of community to build or to join, the issue of sharing versus privacy can be the most helpful. In communities which share private property (collective) as in cohousing, one begins with the assumption of privacy and asks, How much am I willing to share? In communities which share commonly owned property (communal) one begins with the assumption of sharing and asks, How much privacy do I need? The difference is in the often expressed conflict between individuality and collectivity, and each community design finds an appropriate balance between these levels of consciousness, such that neither the individual nor the group is submerged by the other. Communal Mixed-Economy Collective Intentional Intentional Intentional Communities Communities Communities InterThe commu- For some people The family personal nity is the the family may is the Relation- primary be primary, for primary ships social bond others the comm. social bond Shared par- Mutual aid child Some mutual Family aid child care Structure, enting, serial care, diverse among nucmonogomy, family designs Child lear families polyfidelity Care Architectural Design, Land Use Common land & buildings, group residences Private living spaces with group housing & common space No or some common spaces, single family houses

WAVES of COMMUNITARIANISM

1st Wave - 1600s and 1700s, spiritual and authoritarian German/Swiss Pietist and English Separatist. 2nd Wave - 1840s secular: Anarchist Socialist, Associationist, Mutualist Cooperative, Owenite, Perfectionist, and the religious: Christian Socialist, Adventist. 3rd Wave - crested in the 1890s (50 years later) Hutterite, Mennonite, Amish, and first Georgist single-tax colony. 4th Wave - 1930s (40 years later) New Deal Green-Belt Towns, Catholic Worker, Emissary, School of Living. 5th Wave - 1960s (30 years later) peace/ecology/feminism. 6th Wave - 1990s cohousing, ecovillages, various networks.

OWNERSHIP-CONTROL MATRIX

Common Ownership of Wealth Consensus process control of wealth (win-win) Majority rule and other win-lose processes Egalitarian Communalism. Sharing common property, and income. Democratic Communalism. Common equity (some Israeli Kibbutzim). Mixed Economic Systems Egalitarian Commonwealth. (land trusts; communal cores) Democratic Commonwealth. Capitalism & socialism. Private Ownership of Wealth Egalitarian Collectivism. Sharing private property (cohousing). Economic Democracy. All cooperatives. (Mondragon)

TWO METHODS of DESCRIBING INTENTIONAL COMMUNITIES:

DESCRIPTIVE TERMS focus upon the primary shared concern, value or characteristic held by a particular community. Examples: Christian community, Yoga society, activist, back-to-theland, etc. Those that are part of networks use a catagorical name, such as land trust, cohousing, ecovillage, or a network name such as Carmalite nunnery and Emissary community. CLASSIFICATIONS compare socio-cultural factors in different communities. A relative measure, such as a continuum, presents a range of different approaches to particular issues. Example: governmental forms may range from authoritarian to participatory decisionmaking processes. Continua can be arranged in two-dimentional matrices, such as for politicaleconomic structures.

DEFINITIONS of TERMS

COMMUNITY - a group of people sharing any common identity or characteristic, whether geographic, economic, political, spiritual, cultural, psychological, etc. COMMUNITARIANISM - the idea and practice of mutual responsibility by members of a society. CIRCUMSTANTIAL COMMUNITY - a group of people living in proximity by chance, such as in a city, neighborhood or village, the residents of which may or may not individually choose to be active participants in the pre-existing association. INTENTIONAL COMMUNITY - a fellowship of individuals and families practicing common agreement and collective action.

Plutocratic Authori- Totalitarianism Authoritarianism. Capitalism. Complete tarian Labor credit Individual inPrivate Labor Corporate control of social control. Theocracy. come labor with businesses, Systems, systems, Communism. Patriarchy. Fascism. wealth Manage- Community community labor some group The two aspects of society and culture that businesses projects labor projects ment combine to create distinctively different patterns are: decision-making structures and methods of property Property Commonly Some common, Private some private property & ownership. Together these are called a politicalowned Codes, equity economy, and they can be explained by placing the assets/equity property Equity two continua, government (beliefs or control) and economics (sharing/privacy or ownership), at right philosophy, but not economic processes. Pluralist Belief Structure: Secular; Open society; Inclusive; IntegraPLURALISTangles to each other, forming a matrix. Either circumstantial or intentional Thus, very different economic systems can tionist; Expressed individuality; Participatory. Examples: to-UNIFIED have the same belief structure. Complications: community can function as the other. cohousing, land trust, egalitarian community. The political-economic matrix can be used to model the For example, an intentional community cross-overs exist between Pluralism and Few Common Beliefs: Group has a shared belief but is tolerant of entire range of human organization, from community to city BELIEFS may abandon its common agreements, Few Common Beliefs, and these may use differences. Ex. ecovillages (ecology), Kibbutz Artzi (Zionism). to nation-state to global civilization. It can also be used to causing the people to drift apart, or a CONTINUUM either consensus or democratic decisionUnified Belief Structure: Dogmatic; Closed/Class society; Exclusive; track the changes in a given culture over time, since when a town may pull together in collective Beliefs include spirit- making processes. Communities with uniform Isolationist; Suppressed individuality; Authoritarian. Examples: group or a country changes its economy or form of governaction to respond to a common threat. uality, religion and beliefs often have authoritarian governments. monasteries, Hutterites, Kibbutz Dati (Zionism/Judism). ment, it would move from one cell in the matrix to another.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Bullet Points: Reasons To Vote FOR Donald J. TrumpDokument5 SeitenBullet Points: Reasons To Vote FOR Donald J. TrumpPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- No Confidence Letter To Whatcom County (Washington) Councils - 2017Dokument4 SeitenNo Confidence Letter To Whatcom County (Washington) Councils - 2017PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- WCSO Memo - Sgt. Steve Cooley DisciplineDokument4 SeitenWCSO Memo - Sgt. Steve Cooley DisciplineLoriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Leftist, #NODAPL, #MayDay 'Protestors'Dokument18 SeitenLeftist, #NODAPL, #MayDay 'Protestors'PRMurphy100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Evidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 3 of 3Dokument72 SeitenEvidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 3 of 3PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Evidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 2 of 3Dokument61 SeitenEvidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 2 of 3PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- PDC Complaint - Gilfilen Vs Whatcom County Officials 11-30-2015Dokument15 SeitenPDC Complaint - Gilfilen Vs Whatcom County Officials 11-30-2015PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Steve Cooley - Civil Service Deposition - 11-09-12 - RedactedDokument89 SeitenSteve Cooley - Civil Service Deposition - 11-09-12 - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Paul R. Murphy: From: Sent: To: CC: Subject: Follow Up Flag: Flag Status: CategoriesDokument4 SeitenPaul R. Murphy: From: Sent: To: CC: Subject: Follow Up Flag: Flag Status: CategoriesPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 1 of 3 PDFDokument63 SeitenEvidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 1 of 3 PDFPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Pennington Co Jail Annex 2nd and 3rd FloorsDokument1 SeitePennington Co Jail Annex 2nd and 3rd FloorsPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Whatcom County Jail Report - Jay FarbsteinDokument16 SeitenWhatcom County Jail Report - Jay FarbsteinPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Evidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 1 of 3 PDFDokument63 SeitenEvidence Addendums To The PDC - Part 1 of 3 PDFPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Jihad That Lead To The Crusades - WarnerDokument17 SeitenThe Jihad That Lead To The Crusades - WarnerPRMurphy100% (1)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Case Study: Pennington Co, SD Jail AnnexDokument1 SeiteCase Study: Pennington Co, SD Jail AnnexPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Defense Expert Witness - Hard Drive Forensics - A38-Mitchell Report 2-17-14Dokument73 SeitenDefense Expert Witness - Hard Drive Forensics - A38-Mitchell Report 2-17-14PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Bill Elfo - Civil Service Deposition - 11-9-12Dokument18 SeitenBill Elfo - Civil Service Deposition - 11-9-12PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gulf Rd. Trails - Parks' Denial Email - 07-11-08 - PG 1Dokument1 SeiteGulf Rd. Trails - Parks' Denial Email - 07-11-08 - PG 1PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Exhibit 60 - Longarm Case Report Narrative - BPDDokument13 SeitenExhibit 60 - Longarm Case Report Narrative - BPDPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gulf RD Trails - Parks Email - 07-09-08Dokument3 SeitenGulf RD Trails - Parks Email - 07-09-08PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gulf Rd. Trails - Grievance Letter - Francis - 08-06-08Dokument2 SeitenGulf Rd. Trails - Grievance Letter - Francis - 08-06-08PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Chief Arthur Edge, WCSO - 03-11-14 Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedDokument20 SeitenChief Arthur Edge, WCSO - 03-11-14 Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

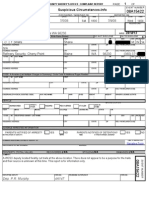

- Gulf Rd. Trails Police Report: 08A15422 SuspCirc - RedactedDokument2 SeitenGulf Rd. Trails Police Report: 08A15422 SuspCirc - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sgt. Kevin Mede, WCSO - Deposition (Federal) - Full TranscriptDokument60 SeitenSgt. Kevin Mede, WCSO - Deposition (Federal) - Full TranscriptPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steven Cooley, WCSO - Vol II - Minor RedactionDokument25 SeitenSteven Cooley, WCSO - Vol II - Minor RedactionPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deputy X5, WCSO - Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedDokument15 SeitenDeputy X5, WCSO - Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- I520 '426' Flags Email - Kevin Mede - RedactedDokument1 SeiteI520 '426' Flags Email - Kevin Mede - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lt. Scott Rossmiller, WCSO - Deposition Transcript (Federal)Dokument66 SeitenLt. Scott Rossmiller, WCSO - Deposition Transcript (Federal)PRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Deputy X19 - Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedDokument21 SeitenDeputy X19 - Deposition Transcript (Federal) - RedactedPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steven Cooley, WCSO - Vol I - Full TranscriptDokument35 SeitenSteven Cooley, WCSO - Vol I - Full TranscriptPRMurphyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Feeling in Relationship UHV CourseDokument54 SeitenFeeling in Relationship UHV CoursebinuNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Father's Advice To His DaughterDokument4 SeitenA Father's Advice To His Daughterrlweisman100% (3)

- The Human Person Flourishing in Terms of Science And: Weeks 7-8 Technology Technology As A Way of RevealingDokument34 SeitenThe Human Person Flourishing in Terms of Science And: Weeks 7-8 Technology Technology As A Way of RevealingJaylordPalattaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book ReviewsDokument53 SeitenBook ReviewsSantosh SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- The ABCs of Living A Happy LifeDokument2 SeitenThe ABCs of Living A Happy LifePhung Thanh ThomNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Good LifeDokument23 SeitenThe Good LifenicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Happiness and Place: Cities V Nature. Why Life Is Better Outside of The City?Dokument79 SeitenHappiness and Place: Cities V Nature. Why Life Is Better Outside of The City?nosequeinventarmeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human FlourishingDokument22 SeitenHuman FlourishingESCOBAR, Ma. Michaela G.- PRESNoch keine Bewertungen

- NSTP Chapter 3Dokument32 SeitenNSTP Chapter 3Grecel Joy BaloteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- How To Connect With Your Inner Power?Dokument29 SeitenHow To Connect With Your Inner Power?S.GumboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three Contemporary Questions: Etsi Deus Non Daretur - An Expression That Highlights TheDokument4 SeitenThree Contemporary Questions: Etsi Deus Non Daretur - An Expression That Highlights TheRona Via AbrahanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leo Strauss - Reason and Revelation (1948)Dokument40 SeitenLeo Strauss - Reason and Revelation (1948)Giordano BrunoNoch keine Bewertungen

- GE 9 10805 Midterm Exam ReviewerDokument5 SeitenGE 9 10805 Midterm Exam ReviewerJackie B. CagutomNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Good Life: A. QuestionsDokument3 SeitenThe Good Life: A. QuestionsWyeth Earl Padar EndrianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- TIBETAN Calendar 2012Dokument23 SeitenTIBETAN Calendar 2012hugodegalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Booklet 12Dokument7 SeitenBooklet 12OSZEL JUNE BALANAYNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Mindful Couple - How Acceptance and Mindfulness Can Lead You To The Love You WantDokument95 SeitenThe Mindful Couple - How Acceptance and Mindfulness Can Lead You To The Love You Wantmartafs-1100% (3)

- The Nature of MaterialismDokument14 SeitenThe Nature of MaterialismYam YamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics 9Dokument6 SeitenEthics 9Melanie Dela RosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Ethics & Corporate Governance (Be & CG) - Sem Iv-GtuDokument88 SeitenBusiness Ethics & Corporate Governance (Be & CG) - Sem Iv-Gtukeyur90% (61)

- Utilitarianism ExplainedDokument3 SeitenUtilitarianism ExplainedFrancisJoseB.PiedadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Term PaperDokument1 SeiteTerm PaperKessa CebrianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample IELTS Writing Task 2 SimonDokument25 SeitenSample IELTS Writing Task 2 SimonLê Hữu ThắngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leaman - Maimonides and Natural LawDokument16 SeitenLeaman - Maimonides and Natural Lawinvisible_handNoch keine Bewertungen

- 17 Rules of Happiness by Karl MooreDokument7 Seiten17 Rules of Happiness by Karl MooreAgus RiyadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- STS L5 Indigenous Science and Technology in The PhilippinesDokument5 SeitenSTS L5 Indigenous Science and Technology in The PhilippinesKrizzia DizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- AGK Buddhism EssayDokument7 SeitenAGK Buddhism EssayAaron KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jyotish - Brighu Prashna Nadi - RG RaoDokument161 SeitenJyotish - Brighu Prashna Nadi - RG RaoParameshwaran Shanmugasundharam91% (11)

- Finding Your FlowDokument29 SeitenFinding Your Flowmarianaluca100% (1)

- Ei Case 1 - Group 5Dokument9 SeitenEi Case 1 - Group 5Radhika ShingankuliNoch keine Bewertungen