Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Aids and Climate Paper

Hochgeladen von

samikasOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Aids and Climate Paper

Hochgeladen von

samikasCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Climate Change Incieasing the ulobal

Thieat of BIvAIBS

repared lor ur ChrlsLlanne SLephens

An1P8C 3C03 PLAL1PLnvl8CnAn1P8C A8 PL1PACL 3CC3

March 30 2011

Sandra Macdonald

9402813

Introduction

The suggestion oI direct correlations between climate change and the HIV/AIDS

pandemic may seem at Iirst perplexing, iI not improbable. While both concerns bring broad scale

crises threatening to change humanity in a spectrum oI populations, it is only in the last Iew

years that research is Iocusing a lens on identiIying the impact oI the changing environmental

conditions on the distribution and Irequency oI HIV inIection, and vice-versa. Much oI the

literature on climate change mentions HIV/Aids as a background or secondary Iactor in current

and expected mortality rates caused by climate change. For example, a 2003 report published by

the WHO indicates that inIectious diseases are on the rise in tandem with the current increase in

climate events and global warming, but stops well short oI suggesting and direct or indirect links

(Kovats, Ebi, & Menne, 2003). Furthermore, authoritative reports on HIV/Aids including the

2002 and 2003 UNAIDS studies, neglect to include any signiIicant research on climate and

correlations to transmission rates and dissemination patterns oI HIV (UNAIDS, 2002)

(UNAIDS/WHO, 2003). More recently, however, investigations into deIinitive links are being

undertaken by prominent scientists and sociologists. In a recent article published by Mongo Bay

news David Cooper, director oI the National Centre in HIV Epidemiology and Clinical Research

in Australia indicated that nutritional impacts caused by changing environmental conditions will

put the immunocompromized at a greater risk oI dying oI HIV (McLean, 2008). The same article

cites a leading proIessor oI health and human rights at the University oI New South Wales as

stating that a 'chain oI events caused by climate instability will result in vulnerability increases

to inIectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS. With pessimism in the Iorecast Ior a vaccine by

scientists predicting at least one or two decades Ior its development (McLean, 2008), it should be

paramount to develop a clear understanding oI how current and impending climate Ilux will alter

the disease transmission patterns in order to develop strong mitigation and coping strategies.

The spread oI HIV/AIDS and the impact oI climate change have many commonalities.

Populations with the least amount oI resources are aIIected the most, and there is a lack oI

political support and technical capabilities to contain either calamity. Additionally, just as

HIV/AIDS exacerbates poverty, gender vulnerability, exploitation oI children, and access to

health care, so too does climate change heightens these same social disparities. The background

Iactors and vulnerabilities that create the conditions Ior increasing HIV/AIDS risk are either

directly or indirectly inIluenced by changing climate conditions. Ecological changes in general

combined with social and political Iactors such as increasing population growth, mass migration

and mobility, growing urban centers and overcrowding, poor sanitation, poverty and hunger,

resource allocation, education and Iailure oI political eIIort can all be linked to the changing

environment, and lead to increasing inIection rates oI HIV/AIDS (Crewe, 2009). Additionally,

climate Iactors can aIIect human resilience and innate immunity to inIectious diseases, and

threaten the biological resources that could provide treatments and therapies in the Iuture

(Napier, et al., 2009). Using a medical ecology and biological approach, these Iactors can be

linked to climate change through cultural, physical, political and biological activities and

phenomenon, all leading to increased risk oI HIV/AIDS proliIeration.

IVJAIDS: A Social Pandemic

It is important to internalize that by and large the HIV/AIDS pandemic is rooted in social

processes. The Iirst reason Ior this is due to the physical transmission mechanisms Ior the

disease. Without strong evidence Ior vector-based transmission, HIV/AIDS is nearly exclusively

transmitted through sexual and drug-injection networks (Bluthenthal, Lorvick, Kral, Edlin, &

Khan, 1999), which in themselves are largely social phenomenon. Social norms which shape the

variables oI these networks, such as timing and number oI sexual partners, injection and drug use

patterns, community support, education and law enIorcement policies are all subject to disruption

by both long term and acute crises. Wars, revolutions, socioeconomic transitions, economic

collapses, and ecological disasters in recent years have lead to large-scale HIV outbreaks, mostly

due to rapid disruptions oI the social mechanisms that governed the aIIected populations. For

example, economic hardship aIter the disruption oIten leads some people to sell sex Ior goods or

money, putting individuals at high risk Ior inIection and transmitting inIections to large numbers

oI other people (Friedman, Rossi, & Flom, 2006). Additionally, social disruption and the

emergence oI disease as a result is oIten heightened by additional environmental stressors.

limate ange and te Food risis

Although rising rates oI HIV/AIDS inIection in industrialized nations are being reported,

and there are grave concerns about possible explosions in rates oI transmission in the Asian

block countries, sub-Saharan AIrica, with less than 15 percent oI the world`s population, still

bears the brunt oI the overall inIections, with over 70 oI the worlds HIV/AIDS cases coming

Irom this area (Crewe, 2009). This area is one whose history is studded with strains on Iood

security, Irom outright Iood shortages in the 1970`s to lack oI access Ior the masses oI urban

poor due to pricing structures throughout the 1990`s and 2000`s (Maxwell, 1999). The near

absence oI social nets has shiIted the issues oI Iood security to the individual. The eIIect oI

environmental change on agriculture and Iood supplies is already becoming evident. Increasing

droughts has resulted in a drop in crop yield, increases in pests, and loss oI Iertile land (Cook,

1992). Climate change will continue to compound the existing Iood insecurity. The

simultaneous occurrence oI HIV/AIDS and Iood insecurity in AIrica is so proIound that some

researchers have nicknamed it the 'deadly duo (Gommes, de Guerny, Glantz, & Hsu, 2004). A

report by OXFAM investigated the Iactors leading to the current Iood crisis, and climatic Iactors

were at the IoreIront (Gommes, de Guerny, Glantz, & Hsu, 2004) . They stressed that the

improvement oI the Iood situation would not only quell the transmission, but also work to reduce

the HIV/AIDS pandemic overall. It is well established that under nutrition and inIection act

synergistically (Bluthenthal, Lorvick, Kral, Edlin, & Khan, 1999), and improvements in Iood

security will reduce the probability oI HIV inIection and slow the progression Irom HIV to

AIDS.

limate ange as a Driver for Mobility and Increased Population Density

The movement oI people and increases in population density may together present the

largest Iactor in determining vulnerability to HIV/AIDS (Gommes, de Guerny, Glantz, & Hsu,

2004). Mobility is generally a strategy Ior adaptation to environmental and political stressors, but

with globalization and mass population movements, the transmission oI diseases across both

geographical and cultural borders is a concern (McElroy & Townsend, 2009). Population growth

and clustering in urban areas interIaces with climate change in ways that ampliIy other

mechanism at work in the HIV/AIDS vulnerability Iramework, namely shelter, Iood, and water

scarcity (Napier, et al., 2009).

Large temporary populations Irequently occur and will continue to grow due to various

types oI climate-based disasters, including Ilooding, earthquakes, and extreme weather events.

So called 'environmental reIugees can also be displaced by drought or other Iactors such as

rising sea levels Iorcing them to abandon their living areas and land (Kovats, Ebi, & Menne,

2003). Over 25 million environmental reIugees have been created by climate and weather events,

and some predictions place over 100 million at risk Irom coastal Ilooding by 2100 (The

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2007). Migrant and displaced populations are at a

higher risk oI contracting HIV/AIDS primarily due to their status and situations they must Iace,

including poverty, lack oI inIormation and health resources, discrimination and stigma.

Poverty and lack oI opportunity, particularly Ior women who make up the majority oI the

agricultural workIorce hardest hit in an environmental crisis, can lead to migration to urban

areas, where they are Iorced into dangerous work in the drug trade and prostitution (United

Nations Food Populations Fund, 2007). The possibilities oI entrepreneurial activities in the sex

or drug trades may be improved during climate-based disasters. This can arise due to the

combination oI an increase in potential workers due to economic desperation and migration plus

a weakening oI police controls over these activities due to institutional disruption, lack oI

resources or an increased willingness oI law authorities to look the other way (Friedman, Rossi,

& Flom, 2006).

When climate disasters cause a large scale movement oI people, they oIten weaken or

completely disintegrate the system oI social norms, support networks, and inIluence that Iorm a

basis oI regulation in communities (Kovats, Ebi, & Menne, 2003). People who have spent their

entire lives surrounded by close Iriends and relatives with established communication networks

Ior expressing their well being, and more importantly, expressing and accepting authoritative

opinions on how people should conduct their lives, can suddenly Iind themselves in temporary

living arrangements or urban centres where none oI this is available. This phenomenon can

increase the probability that some will undertake what was previously unacceptable behaviour,

such as drug use, violence, and risky sexual activity (Friedman, Rossi, & Flom, 2006), all

signiIicant risk Iactors Ior contracting HIV (Bluthenthal, Lorvick, Kral, Edlin, & Khan, 1999).

HIV/AIDS may itselI be a cause oI migration. People living with HIV are oIten driven to

leave their homes and Iamilies, both due to shame and stigma and the lack oI health resources

outside oI urban areas. Migrants living with HIV are subject to additional Iorms oI

discrimination due to Iactors such as ethic origin, religious belieIs, socio-economic status, and

migration and living status. This type oI migration stress illustrates the vicious cycle oI poverty

that is reinIorced by AIDS and climate change. 36 oI the world population lacks access to

health care, and Ior many oI the worlds working poor an HIV/AIDS diagnosis oIten leads to job

loss with no compensation or health care support (Unrepresented Nations and Peoples

Organization, 2006).

limate ange and Immunity Implications

Social Iactors aIIecting the prevalence and distribution oI HIV/AIDS will be increasingly

joined by biological and physiological Iactors inIluenced by climate change. In addition to under

nutrition, other important causes oI immune suppression such as environmental pollutants and

ozone depletion may directly suppress immune responses, and render individuals more

susceptible to acquiring pathogens such as HIV (Kovats, Ebi, & Menne, 2003). Immunity to

inIectious diseases is mediated by a biological response which is compromised by ultraviolet

light exposure. Exposure to excess summer sun due to inIrastructure loss by climate disaster,

increase oI UV-B radiation due to atmospheric changes or both will decrease immunity cell

concentrations, and leave individuals more susceptible to inIection (Cook, 1992).

Immunosupression Irom exposure to other climate change exacerbated pathogens also plays a

role in increasing the threat oI HIV/AIDS. Climate changes have been shown to increase the

prevalence oI certain disease vectors such as mosquitoes responsible Ior yellow Iever, dengue

and malaria (Cook, 1992). Additionally, overcrowding, under nutrition, lack oI access to health

care, urbanization and disturbed social conditions, all precipitated by climate change, can lead to

increases in immune compromising conditions such as tuberculosis, leprosy, measles, parasites

and the plague (Cook, 1992),.

Human health is dependent upon the biodiversity oI the earth. The largest direct cause oI

lost oI biodiversity is the conversion oI land Ior agricultural use, and the subsequent destruction

oI habitat. This practice is one oI the leading anthropological causes oI the current global

warming trends, which in turn leads to Iurther habitat destruction through weather related

disasters, drought, erosion and other longer term changes. There needs to be an appreciation oI

the impact oI not only destroying the organisms themselves, but also the intricate network oI

interactions between species which can hold valuable clues to the discoveries oI new

pharmaceutical and traditional treatments (Daily & Ehrlich, 1996). The delicate network oI

interactions between the species is paramount Ior the discovery oI unique treatments and cures oI

disease. In Iact, 118 out oI 150 top prescription drugs are based on chemical compounds

harvested Irom other organisms (Farhsworth, 1988). Because oI this, climate change poses a

threat to the prognosis oI long term treatment options and a cure Ior HIV/AIDS.

allenges in Resource Allocation

In an interesting social and political tug oI war, climate change, even with its signiIicant impact

on HIV/AIDS, may be directing media attention and government support away Irom issues in human

health. Indeed, the attention that climate change has received in the media and in scientiIic study has been

relatively narrow. For example, investigations into the impact oI increasing levels oI atmospheric carbon

dioxide have been undertaken largely without consideration oI the direct and indirect impacts that this has

on human health (Ziska, Gebhard, Frenz, & Faulkner, 2003). This phenomenon is causing a shiIt in

resource allocation that threatens the advancements that have been made in Iighting the disease. Bjorn

Lomborg oI the Copenhagen Consensus Center provides an illustration oI the struggle between the issues

through a story Irom Tanzania. He claims that 10,000 tourists are drawn to Mount Kilimanjaro in

Tanzania, driven in no small part by the Iear that the mountain's magniIicent ice will soon melt (Lomborg,

2009). Some experts reIute the claims that the receding glaciers are indeed due to global warming,

however climate activists have managed to promote local tourism and have brought the world's attention

to the mountain's glaciers. What has been neglected is bringing attention to the actual people oI Tanzania,

and their battle with HIV/AIDS. Mr. Lomborg suggests that the resources used to promote tourism and

bring attention to the melting ice could better be used to provide public education about HIV in order to

reduce the stigma Ior those aIIlicted, and slow the transmission rates in the country.

In the same theme oI resource allocation, climate change and its related consequences threaten to

tax resource systems to maximum levels, depleting resource pools previously dedicated to the Iight

against HIV/AIDS. Progress on HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment, and care is plateauing as major Iinding

sources begin to ration resources, their coIIers running low (Stockman, 2010). II existing health needs are

excluded Irom climate change adaptation strategies then it is likely that climate change will act as a

competitor, detracting attention and Iunding away Irom current needs and investing in strategies that may

not deliver any signiIicant health improvement (Hall, 2009). At a time when it seems as though

medication costs, education trends, and viable long term treatments seem to be nearing the tipping point

Iunding is being capped or diverted away Irom the cause (Stockman, 2010). By understanding the

interrelations between climate change and HIV/AIDS a concerted eIIort and resource pooling may be a

viable strategy Ior mitigating the eIIects oI both concerns.

onclusions

By taking a step back and investigating HIV/AIDS within a broader Iramework, it becomes

evident that although there are speciIicities with respect to management oI the disease, interactions

between the environment, social structures, migration and other inIectious diseases exist, and are growing

rapidly in importance. It is imperative to complement existing eIIorts and to advocate looking beyond the

Ilat Iace oI AIDS and stop dealing with it in isolation. IdentiIying and recognizing climate and

environmental Iactors as warning signs Ior the dissemination and growth oI the disease is imperative in

creating development strategies that can pre-empt or mitigate the root causes oI HIV/AIDS. Continued

discussion needs to be initiated among Iunders, media, biological and social researchers to encourage the

continuation oI concerted eIIorts in dealing with the eIIects oI both climate change and HIV/AIDS.

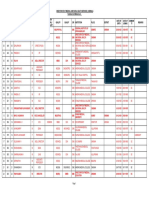

orks ited

luLhenLhal 8 Lorvlck ! kral A Ldlln khan ! 1999 CollaLeral damage ln Lhe war on drugs Plv

rlsk behavlors among ln[ecLlon drug users lnLernaLlonal lnLervenous urug ollcy 2338

Cook C 1992 LffecL of global warmlng on Lhe dlsLrlbuLlon of paraslLlc and oLher lnfecLlons dlseases

!ournal of Lhe 8oyal SocleLy of Medlclne 688691

Crewe M 2009 1he aLLern of 8esponse Lo Plv/AluS CllmaLe Change A CommenLary 8eLrleved

lebruary 23 2011 from un Chronlcle

hLLp//wwwunorg/wcm/conLenL/slLe/chronlcle/home/archlve/lssues2009/pld/3067

ually C Lhrllch 1996 Clobal change and human suscepLlblllLy Lo dlsease Annual 8evlew of Lnergy

adn Lhe LnvlronmenL 124144

larhsworLh n 1988 Screenlng planLs for new medlclnes lodlverslLy 8397

lrledman S 8ossl u llom 2006 lg LvenLs" and neLworks ConnecLlons 914

Commes 8 de Cuerny ! ClanLz M Psu Ln 2004 CllmaLe and Plv/AluS angkok unu

Pall v 2009 CllmaLe Change and PealLh A Lens Lo 8efocus on Lhe Lhe oor CommonwealLh SecreLarlaL

18

kovaLs S Lbl k L Menne 2003 MeLhods of asseslng human healLh vulnerapblllLy and publlc

healLh adapLaLlon Lo cllmaLe change Ceneva WPC

Lomborg 2009 uecember 7 Clobal Warmlng and ML klllman[aro 1he Wall SLreeL !ournal p

Cplnlon

Maxwell u 1999 1he ollLlcal Lconomy of urban lood SecurlLy ln SubSaharan Afrlca World

uevelopmenL 19391933

McLlroy A 1ownsend k 2009 Medlcal AnLhropology ln an Lcologlcal erspecLlve hlladelphla

WesLvlew ress

McLean 1 2008 Aprll 30 Clobal warmlng seL Lo fan Lhe Plv flre 8eLrleved lebruary 1 2011 from

Mongo ay hLLp//newsmongabaycom/2008/0430hlvhLml

napler u 8edcllfL n agel C 8ees P 8ogger u eL al 2009 Managlng Lhe healLh effecLs of cllmage

change 1he LanceL 16391733

SLockman l 2010 Aprll 9 uS seeks Lo reln ln AluS program osLon Clobe p 3

1he lnLergovernmenLal anel on CllmaLe Change 2007 lourLh CllmaLe Change AssessmenL angkok

World MeLeorologlcal CrganlzaLlon (WMC) and Lhe unlLed naLlons LnvlronmenL rogramme

(unL)

unAluS 2002 8eporL on Lhe Clobal Plv/AluS Lpldemlc Ceneva unAluS

unAluS/WPC 2003 Alds Lpldemlc updaLe Ceneva unAluS

unlLed naLlons lood opulaLlons lund 2007 SLaLe of Lhe world populaLlon 2007 new ?ork unlA

unrepresenLed naLlons and eoples CrganlzaLlon 2006 SepLember 14 aLwa Sexual vlolence Lack of

PealLhcare Spreads Plv/AluS 8eLrleved March 14 2011 from unrepresenLed naLlons and

eoples CrganlzaLlon hLLp//wwwunpoorg/arLlcle/3423

Zlska L P Cebhard u L lrenz u A laulkner S 2003 ClLles as harblngers of cllmaLe

changeCommon ragweed urbanlzaLlon and publlc healLh !ournal of Allergles and Cllnlcal

lmmunology 290293

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Social Work MaterialDokument214 SeitenSocial Work MaterialBala Tvn100% (2)

- Part-IDokument507 SeitenPart-INaan SivananthamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vince Gironda 8x8 RoutineDokument10 SeitenVince Gironda 8x8 RoutineCLAVDIVS0% (2)

- Amy L. Lansky - Impossible Cure - The Promise of HomeopathyDokument295 SeitenAmy L. Lansky - Impossible Cure - The Promise of Homeopathybjjman88% (17)

- Glycerol MsdsDokument6 SeitenGlycerol MsdsJX Lim0% (1)

- Rafika RespitasariDokument8 SeitenRafika RespitasariYeyen SatriyaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becas Taiwan ICDFDokument54 SeitenBecas Taiwan ICDFlloco11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bed Making LectureDokument13 SeitenBed Making LectureYnaffit Alteza Untal67% (3)

- EQ-5D-5L User GuideDokument28 SeitenEQ-5D-5L User GuideCristi100% (1)

- Chapter 020Dokument59 SeitenChapter 020api-263755297Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chevron Phillips Chemical Company Issued Sales SpecificationDokument1 SeiteChevron Phillips Chemical Company Issued Sales SpecificationSarmiento HerminioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life-Long Learning Characteristics Self-Assessment: Behavioral IndicatorsDokument2 SeitenLife-Long Learning Characteristics Self-Assessment: Behavioral Indicatorsapi-534534107Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Miracle of ChocolateDokument10 SeitenThe Miracle of ChocolateAmanda YasminNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 8 - P.E PPT (Week 1)Dokument30 SeitenGrade 8 - P.E PPT (Week 1)Dave Sedigo100% (1)

- Basic Education For Autistic Children Using Interactive Video GamesDokument5 SeitenBasic Education For Autistic Children Using Interactive Video GamesEwerton DuarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engl7 Q4 W4 Determining-Accuracy Villanueva Bgo Reviewed-1Dokument18 SeitenEngl7 Q4 W4 Determining-Accuracy Villanueva Bgo Reviewed-1johbaguilatNoch keine Bewertungen

- A 58 Year Old Client Is Admitted With A Diagnosis of Lung CancerDokument9 SeitenA 58 Year Old Client Is Admitted With A Diagnosis of Lung CancerNur SanaaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- 57 2 3 BiologyDokument15 Seiten57 2 3 BiologyAadya SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urbanization and HealthDokument2 SeitenUrbanization and HealthsachiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laboratory Result Report: Requested Test Result Units Reference Value Method ImmunologyDokument1 SeiteLaboratory Result Report: Requested Test Result Units Reference Value Method ImmunologyYaya ZakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 2 - Up-Fa1-Stem11-19 - Chapter IiDokument7 SeitenGroup 2 - Up-Fa1-Stem11-19 - Chapter IijamesrusselNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cut-Off Points For Admission Under The Government Sponsorship Scheme For The Academic Year 2015/2016.Dokument4 SeitenCut-Off Points For Admission Under The Government Sponsorship Scheme For The Academic Year 2015/2016.The Campus Times100% (1)

- Working in A Lab Risk & AssessmentDokument10 SeitenWorking in A Lab Risk & AssessmentMariam KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Junal 1Dokument6 SeitenJunal 1indadzi arsyNoch keine Bewertungen

- NBR Leaflet Krynac 4955vp Ultrahigh 150dpiwebDokument2 SeitenNBR Leaflet Krynac 4955vp Ultrahigh 150dpiwebSikanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- AssignmentDokument2 SeitenAssignmentReserva, ArchelleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatrics-AAP Guideline To SedationDokument18 SeitenPediatrics-AAP Guideline To SedationMarcus, RNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective Leadership Towards The Star Rating Evaluation of Malaysian Seni Gayung Fatani Malaysia Organization PSGFMDokument10 SeitenEffective Leadership Towards The Star Rating Evaluation of Malaysian Seni Gayung Fatani Malaysia Organization PSGFMabishekj274Noch keine Bewertungen

- AnsdDokument12 SeitenAnsdAlok PandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tre Mad OdesDokument31 SeitenTre Mad OdesmoosNoch keine Bewertungen