Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Vaccinations For Sheep and Goats

Hochgeladen von

kitemetseOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Vaccinations For Sheep and Goats

Hochgeladen von

kitemetseCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Vaccinations for sheep and goats

Vaccinations are an integral part of a flock health management program. They provide cheap insurance against diseases that commonly affect sheep and goats. Probably, the only universally recommended vaccine for sheep and goats is CD-T. CD-T toxoid provides three-way protection against enterotoxemia (overeating disease) caused by Clostridium perfringins types C and D and tetanus (lockjaw) caused by Clostridium tetani. Seven and 8-way combination vaccines for additional clostridial diseases such as blackleg and malignant edema are available, but generally not necessary for small ruminants. Enterotoxemia type C, also called hemorrhagic enteritis or "bloody scours," mostly affects lambs and kids during their first few weeks of life, causing a bloody infection of the small intestine. It is oftenrelated to indigestion and is predisposed by a change in feed, such as beginning creep feeding or a sudden increase in milk supply. Enterotoxemia type D, also called "pulpy kidney disease," usually affects lambs and kids over one month of age, generally the largest, fastest growing lambs/kids in the flock. It is precipitated by a sudden change in feed that causes the organism, which is already present in the young animal's gut to proliferate, resulting in a toxic reaction. Type D is most commonly observed in animals that are consuming high concentrate diets, but can also occur in lambs/kids nursing heavy milking dams. To confer passive immunity to lambs and kids through the colostrum, ewes and does should be vaccinated 2 to 4 weeks prior to parturition. Females giving birth for the first time should be vaccinated twice in late pregnancy, about four weeks apart. Maternal antibodies will protect lambs and kids for about two months, if offspring have ingested adequate colostrum. Lambs/kids should receive their first CD-T vaccination when they are 6 to 8 weeks old, followed by a booster 2 to 4 weeks later. If pastured animals are later placed in a feed lot for concentrate feeding, producers should consider re-vaccinating them for enterotoxemia type D. Lambs and kids whose dams were not vaccinated for C and D can be vaccinated with some success at two to three days of age and again in two weeks. However, later vaccinations will be more successful since colostral antibodies interfere with vaccinations at very young ages. A better alternative may be to vaccinate offspring from non-vaccinated dams at 1 to 3 weeks, with a booster 3 to 4 weeks later. Anti-toxins can provide immediate short-term immunity if dams were not vaccinated or in the event of disease outbreak or vaccine failure. Lambs and kids whose dams were not vaccinated for tetanus should be given the tetanus anti-toxin at the time of docking, castrating, and disbudding, especially if elastrator bands are used. Rams and bucks should be boostered annually with CD-T.

In addition to CD-T, there are other vaccines that sheep and goat producers may include in the flock vaccination program, depending upon the health status of their flock and the diseases prevalent in their area.

Soremouth There is a vaccine for sore mouth (contagious ecthyma, orf), a viral skin disease commonly affecting sheep and goats. It is a live vaccine that causes sore mouth lesions at a location (on the animal) and time of the producers choosing. Ewes should be vaccinated well in advance of lambing. To use the vaccine, a woolless area on the animal is scarified, and the re-hydrated vaccine is applied to the spot with a brush or similar applicator. Ewes can be vaccinated inside the ear or under the tail. Lambs can be vaccinated inside the thigh. Because the sore mouth vaccine is a "live" vaccine and sore mouth is highly contagious to humans, care must be taken when applying the vaccine. Gloves should be used. Flocks which are free from sore mouth should probably not vaccinate because the vaccine will introduce the virus to the flock/premises. Once soremouth vaccination is begun, it should be continued yearly.

Footrot Foot rot (and foot scald) is one of the most ubiquitous diseases in the sheep and goat industry. It causes considerable economic loss due to the costs associated with treating it and the premature culling of affected animals. There are two vaccines for foot rot and foot scald in sheep. Neither product prevents the diseases from occurring, but when used in conjunction with other management practices such as selection/culling, regular foot trimming, foot soaking/bathing, etc., can help reduce infection levels. Foot rot vaccines should be administered every 3 to 6 months and especially prior to anticipated outbreaks of hoof problems (i.e. prior to the wet/rainy season).

Caseous lymphadenitis There is a vaccine for caseous lymphadenitis (CLA, cheesy gland, abscesses) in sheep. CLA affects primarily the lymphatic system and results in the formation of abscesses in the lymph nodes. It is highly contagious. When it affects the internal organs, it becomes in a chronic wasting disease. The cost of CLA to the sheep and goat industry is probably grossly underestimated. The CLA vaccine is convenient to use because it is combined with CD-T. The CLA vaccine should only be used in flocks which do not already show signs of CLA infection.

Abortion Abortion is when a female loses her offspring during pregnancy or gives birth to weak or deformed babies. There are vaccines (individual and combination) for several of the agents that cause abortion in sheep: enzootic (EAE, Chlamydia sp.) and vibriosis (Campylobacter fetus). Abortion vaccines should be administered prior to breeding. Risk factors for abortion include an open flock and a history of abortions in the flock. Unfortunately, there is no vaccine (available in the U.S.) for toxoplasmosis, another common cause of abortion in sheep. Since the disease-causing organism is carried by domestic cats, the best protection is to control the farm's cat population by spaying/neutering and keeping cats from contaminating feed sources.

Rabies Though the risk to sheep and goats is usually minimal, rabies vaccination may be considered if the flock is located in a rabies-infected area and livestock have access to wooded areas or areas frequented by raccoons, skunks, foxes, or other known carriers of rabies. Frequent interaction with livestock may be another reason to consider vaccianting. The cost of the rabies vaccine relative to the value of the animals should be considered as well. The large animal rabies vaccine is approved for use in sheep. No rabies vaccine is currently licensed for goats. All dogs and cats on the farm should be routinely vaccinated for rabies. Producers should consult their veterinarian regarding rabies vaccination. In order for vaccination programs to be successful, label directions must be carefully followed and vaccines need to be stored, handled, and administered properly. Only healthy livestock should be vaccinated. It is also important to note that vaccines have limitations and that the immunity imparted by vaccines can sometimes by inadequate or overwhelmed by disease challenge. With the increasing role of small ruminants in small farms and sustainable farming systems and the rapid growth of the meat goat industry, hopefully animal health companies will develop and license more vaccines for sheep and especially goats. Scientists are currently working on vaccines to protect small ruminants against worms. Copyright 2004.

DE-WORMING AND VACCINATION SCHEDULING

Goats as a species are very susceptible to internal parasites, especially stomach worms. In parts of the United States

warm and wet, the stomach worm to be concerned about is Haemonchus contortus, also known as the Barberpole wo worm feeds on blood; if untreated, it causes anemia and death. Infection reaches highest levels in summer. In cold cl brown stomach worm causes diarrhea, ill thrift (the goat does poorly) and, if untreated, death.

Goats are browsers/foragers -- like deer. They need to eat "from the top down" to protect themselves from internal pa goats are forced to graze grasses like cattle and sheep, they will ingest stomach worms. Goats have the fastest metab all ruminants and are picky eaters; they like the newest, tenderest, and most most nutritious plant materials -- the on closest to the ground where the worms are. Dr. Jim Miller, ruminant parisitologist at Louisiana State Unversity, report recent research study indicated that stomach worm larvae were found farther up blades of grass than previously thou

Frequency of deworming ("worming," in goat producers' vernacular) depends upon the wetness/dryness of the area, p density in pens and pasture, when does are scheduled to kid, overall health of the goats, and a host of other things. T of goats that a producer can run on a given parcel of land is NOT based upon available plant materials but rather on h the wormload can be controlled. Goats as a species are dry-land animals. Areas with higher than 30 inches of annual present major challenges to a producer who is trying to raise healthy goats.

This article will describe how deworming and vaccinations are done at Onion Creek Ranch near Lohn, Texas, where av annual rainfall is 20 inches or less in a normal year. This is a breeding stock operation, so management is more intens that of the average commercial goat ranch. This program may or may not work in other areas but will give producers information that should be useful.

The first line of defense against stomach worms is the use of the FAMACHA field examination. Note that FAMACHA onl anemia-producing infections and the primary anemia producer is Haemonchus contortus. FAMACHA provides the prod method of visually observing signs of anemia in a goat. FAMACHA training and certification are available from Dr. Jim GoatCamp every October at Onion Creek Ranch in Texas and at other locations around the USA throughout the year be used as one of multiple tools for monitoring stomach worm infestation. Occasionally FAMACHA can be misleading; of goats who are perfectly healthy also have light pink to white eye membranes, but they are the exception to FAMAC usefulness. Producers should make every effort to attend FAMACHA training to learn the intricacies of using FAMACHA exams on goats.

An over-simplified explanation of FAMACHA is that the producer examines the inner lower eye membrane (not the mo gums) for coloration. Red to bright pink membranes indicate a very low wormload, pink to light pink reflects the need further testing and de-worming, and white means anemia exists and the goat needs immediate medical attention. FAM also indicate anemia that is the result of liver flukes, so the producer should collect fecal samples both in specific goat white to pink eye membranes and randomly in apparently healthy goats for verification of actual worm loads. Perform own fecals can save money on wormers by revealing to the producer when it is time to deworm. Random routine feca examinations may stretch the time between wormings. There is an article entitled "How To Do Your Own Fecals" on th Page at www.tennesseemeatgoats.com and this procedure is also taught at every GoatCamp.

The dewormer of choice at Onion Creek Ranch since January 1990 has been 1% Ivermectin injectable given orally at a one cc per 50 pounds bodyweight (1 cc per 50 lbs.). Occasionally goats with dairy influence (including Boers and Boer need to be dewormed with a *white* dewormer like Safeguard/Panacur or Valbazen to get tapeworms. However, Ten Meat Goats and TexMasters have consistently responded well to the 1% Ivermectin given orally.

Current research indicates that goats in most herds should be examined by FAMACHA testing and dewormed as neede individual basis. Onion Creek Ranch runs close to 1000 goats, and while FAMACHA is used every time a goat is handle reason, it isn't possible to keep up with individual deworming schedules on such a large number of goats. Therefore, e dewormed every six months while susceptible goats are individually treated throughout the year as needed.

Do not rotate dewormers. Use one dewormer until it quits working, then change to another family of dewormers. As a rule, the white-colored dewormers no longer kill stomach worms in most areas of the United States. In wet areas, pro may get a better response from deworming by fasting the goats (take them off grain and hay but not off water) for at hours before deworming. Using a contrast-colored PaintStik crayon (hot pink and fluorescent green show up well), ma forehead of each goat as deworming progresses so that animals are not medicated multiple times. This also saves mo anthelmintics (dewormers) are expensive. Keep the animals in the same pen/pasture for up to 24 hours because they sloughing worms in their feces -- then move them to a fresh clean pen/pasture. However, under many circumstances, dewormed goats that were heavily infested with worms should not be moved to new pasture because whatever worm

retained are resistant to the dewormer that was used, resulting in contaminating the fresh pasture with resistant worm producer obviously does not want a clean pasture full of resistant worms. These choices are something that each prod learn to deal with as it applies to the specific goat-raising operation.

Kids are dewormed the first time at one month of age at Onion Creek Ranch. Deworming kids at an earlier age won't but it is a waste of time and money, because they don't begin to eat significant amounts of solid food until they are ab weeks old. Kids become infected with stomach worms as they graze the ground for plant materials and pick up infecte as they "mouth" everything in sight. Worms can live in a state of hypobiosis (a sort of hybernation) inside the pregnan The dam's birthing process wakes them up and starts their three-week life cycle. When the young kids are first beginn solid foods, the worms are there on the grasses just waiting for the kids to ingest them.

Dewormer dosages should be calculated carefully. Some dewormers can be double- or tripled-dosed without problem, have a very narrow margin of safety. Levamasole (Tramisol) has a very narrow margin of safety. The difference betwe effective dose and the toxic dose is very small. The premise that "more is better" is not correct with medications. Alwa a knowledgeable goat vet or a producer with extensive experience in raising goats before administering medications o to your goats There are now four classes of dewormers: 1) Avermectins (Ivermectin) the "clear" de-wormers; Dectomax and Cydectin are in this category.

2) Benzimidazoles (Valbazen, Safeguard, Panacur, Telmin, Synanthic, Benzelmin, Anthelcide, TBZ): the "white" dewor Warning: Do not de-worm pregnant does with Valbazen. It can cause abortions. 3) Imidothiazole (Tramisol, Levamasole).

4) Amino-Acitonitrile Derivatives (AAD) -- This new class of dewormer, which has been developed by Norvartis and m under the name Zolvix(tm), is currently on the market for sheep in New Zealand and is not available in the US. When might be available in the US is anyone's guess.

Goats have thin hides (relative to other ruminants, such as cattle) and very fast metabolisms. For these reasons, do n dewormers as back drenches on goats. Back drenching goats with anthelmentics has been proven to be both undesira ineffective.

Diatomaceous Earth is currently a popular product which some people believe acts as a dewormer. As of this date, ev which has been done on the de-worming efficacy of DE has proven that it is not effective against internal parasites. If one of those people who believe in DE with an almost religious fervor, please do both yourself and your goats a favor use an ethical dewormer from the list above. It may be that DE will allow longer stretches between deworming. Until a study proves DE's effectiveness against internal parasites, do not rely on it solely to keep your goats dewormed.

Deworming feed additives and deworming blocks are available to be purchased. Unless the producer has the ability to goat individually every day, do not use these products. The producer has no assurance of each goat's having received adequate dosage of deworming medication. The least aggressive animal -- the one least likely to go to the deworming fight for feed containing dewormer additives -- is usually the one who needs it most. So take the time to measure the medication and give it to each animal individually.

The easiest way to give oral deworming medication to a goat is to draw it into a syringe, remove the needle, straddle (facing the same direction as the goat), lock your legs around its middle and place your feet in front of its back hoove mouth with one hand (watch those back teeth), put the syringe into the side of the mouth and over the back of the to push the syringe. If you used feed to entice the goats in order to catch them , make sure it has been chewed and swa first, or expensive dewormer mixed with feed is going to fall from the goat's mouth onto the ground. For orally deworm numbers of goats, Jeffers sells a 20 ml dosing syringe made by Syrvet (item # SP-D1) that the nozzle doesn't fall off major time saver.

If you are injecting deworming medication (the relatively new Cydectin injectable, for example), make sure to have a Epinephrine (vet prescription) on hand for use if the goat goes into shock. You only have seconds to save an animal in

Gel-type wormers generally come in tubes dosage-calibrated for large animals like horses. They are difficult to measu enough amounts for goats and are therefore wasteful of time and money.

External Parasites: The most common external parasite is lice. Lice are prevalent during cool weather. If goats have been treated for wor verified through fecal counts as having tolerable worm loads but they still have rough coats, then the goats probably h Lice infestation tends to look like a goat has had a bad haircut. Lice come in two types: blood-suckers and non-bloodBlood-sucking lice are the most dangerous, putting the goat into an anemic condition which can result in death. Lice n like grains of white rice in the hair coat. Regardless of type of lice, buy a product like Synergized De-Lice and apply it the back of the goat from base of neck to base of tail. Follow the directions carefully. The dosage is quite small and us should be repeated in one to two weeks. For kids under three months of age and pregnant does, use a kitten-safe or flea powder or spray. The adults' product is too strong and dangerous to use on kids. Take care to cover the kid's eye nose, and other mucous membranes. Jeffers (use link below to go to Jeffers) carries topical delice products.

Ticks are another external parasite prevalent in some areas of the USA. Use 5% Sevin Dust topically on adults and Se cut with an equal amount of diatomaceous earth (DE) on kids and pregnant does.

Overeating/Tetanus Vaccinations: Here we have products actually made for goats! CD/T is a combination vaccine which provides long-term protection a Overeating Disease (Enterotoxemia) and Tetanus. Colorado Serum makes a CD/T vaccine called Essential 3+T which d cause injection site abscesses. Jeffers carries it.

Kids should be given their first Essential 3+T vaccination at one month of age. This is shortly after they have begun to food, their rumen has started to develop, the milk stomach has begun to shrink, and the immune system is up and ru vaccination can be given earlier, but it is not likely to be helpful, and thus a waste of money. Give each kid two cc's (2 cutaneously (SQ -- under the skin). This is one of the few medications which dosage is the same regardless of goat's size, sex, breed, religion, race, or national origin. A booster vaccination (also 2 cc's SQ) must be given in three to fou plan on giving the second Essential 3 +T vaccination when the kid is two months old. All adult goats brought anew to property should receive the two-shot series of Essential 3+T. Don't assume that the previous owner used it.

If using a brand other than Colorado Serum's Essential 3+T, don't be surprised if a lump develops at the injection site the immune system's reaction to the vaccine and means it is working; ' however, an injection site abscess does not ha appear to prove the vaccine's effectiveness. Sometimes this lump goes away and other times it remains. Use the Colo Serum brand and avoid this entirely.

Every goat must receive an annual Essential 3+T booster injection of 2 cc's SQ to renew the protection afforded again Overeating Disease and Tetanus. Some producers chose to boost this vaccine every six months. Pregnant does should Essential 3+T booster four to five weeks before they are due to kid. This vaccine must be kept refrigerated and it free high temperatures, so in winter, the producer may need to turn the temperature control on the medicine refrigerator avoid freezing. Do not use it if it has frozen in the bottle. When using the bottle in the field, use a cooler with an icepa

Pneumonia vaccinations: The two most common killers of goats are worms and pneumonia. Vaccinate against the most common forms of pneu using Colorado Serum's Mannheimia Haemolytica-Pasteurella Multocedia Bacterin vaccine. Inject SQ two cc's (2 cc's) month of age and repeat in two to four weeks. Goats added to the producer's herd, kids or adults, should receive the immunization to insure adequate protection.

At Onion Creek Ranch, we vaccinate for both overeating disease/tetanus and pneumonia at one month and again at tw of age, giving the injections on opposite sides of the body SQ over the ribs with a 22 gauge needle.

Most medications have a statement on the label recommending that they be used in their entirety once opened. This i necessarily true and is the manufacturer's way of protecting itself from liability. To prevent contamination of the bottle

contents, put a single needle into the bottle and change syringes and needles each time medication is drawn. Suzanne W. Gasparotto ONION CREEK RANCH 6-13-09

Common Vaccinations for Goats

By Cheryl K. Smith If raising goats is part of your green lifestyle, you can make yourself more sustainable by giving your goats vaccines yourself. Just what vaccines do your goats need to be healthy? Well, most veterinarians recommend that, at a minimum, you vaccinate goats for clostridium perfringens types C and D and tetanus (CDT). This vaccine prevents tetanus and enterotoxemia that's caused by two different bacteria. Yet many breeders don't vaccinate their goats with this or any other vaccine, for different reasons. Vaccinating for enterotoxemia or another disease doesn't always prevent the disease. But in some cases, if a vaccinated goat does get the disease, it will be shorter and less severe, and the goat is less likely to die. And the cost of vaccinating is minor compared with treating the disease or paying to replace a dead goat. A number of vaccines are used to prevent disease in goats. Most of them are approved for use in sheep but not goats. That doesn't mean that they aren't effective or can't be used in goats but that they haven't been formally tested on goats. Most goat owners with small herds usually don't need any vaccines other than CDT. In areas where rabies is rampant, some veterinarians recommend that you vaccinate your goats for rabies, even though it isn't approved for goats. It is a good idea to work with a veterinarian to determine what is right for your circumstances.

Creating a First Aid Kit for Goats

By Cheryl K. Smith If you have only a couple of goats, you probably can afford the occasional veterinary visit. But as your herd grows, you're likely to find that you want to save money and hassle by treating some of their minor ailments or handling some of the health care yourself. But even if you don't want to take over some of this care, you still need to be prepared for those times when a vet isn't available or the problem is minor. The following lists show you what to have on hand in a goat first aid kit. You can get all of them from a feed store, a drug store, or a livestock supply catalog. None require a prescription. Include the following equipment and supplies:

Surgical gloves Drenching syringe for administering medications Cotton balls Gauze bandage Alcohol prep wipes

Elastic bandage Digital thermometer Syringes and needles

Tuberculin needles and syringes for kid injections 20-gauge needles and syringes of various sizes 3 cc, 6 cc, 15 cc

Tube-feeding kit (tube and syringe) for feeding weak or sick kids Small clippers for shaving around wounds Sharp scalpel Sharp surgical scissors

Include these medications:

7 percent iodine Terramycin eye ointment for pinkeye or eye injuries Antiseptic spray such as Blu-Kote for minor wounds Blood stop powder, for hoof trimming injuries Di-Methox powder or liquid for coccidiosis or scours Epinephrine, for reactions to injections Kaolin pectin, for scours Antibiotic ointment, for minor wounds Aspirin, for pain Activated charcoal product, such as Toxiban, for poisoning Children's Benadryl syrup, for congestion or breathing problems Procaine penicillin, for pneumonia and other infections LA-200 or Biomycin, for pneumonia, pinkeye, or infections Tetanus antitoxin, to prevent tetanus when castrating or for deep wounds CDT antitoxin, for treatment of enterotoxemia Milk of magnesia for constipation or bloat

You also want to include these items:

Betadine surgical scrub, for cleansing wounds Probiotics, such as Probios or yogurt with active cultures Powdered electrolytes, for dehydration Fortified vitamin B, for goat polio or when goat is off feed

Hydrogen peroxide, for cleaning wounds Rubbing alcohol, for sterilizing equipment

Using Guardian Animals to Protect Your Goats

By Cheryl K. Smith Many goat owners keep livestock guardian dogs, donkeys, llamas, or alpacas with goats as full-time guard animals. Guardian animals can add a substantial cost in terms of training and upkeep, but they may be well worth the effort and time if they work out. Try to get a guardian animal from a breeder who has used the animals for this purpose and can vouch for (but not guarantee) their pedigree, training, and temperament.

Livestock guardian dogs (LGDs) were bred and have been used for thousands of years to protect goats and sheep in Europe and Asia. They live and bond with the goats, are aggressive toward predators, and are focused on the job. These dogs are traditionally white, which enables them to blend in with the sheep flock and be distinguished from predators. Of the many breeds of livestock guardian dogs, the Great Pyrenees is probably the best known. Other common livestock guardian breeds include

Akbash Anatolian Komodor Kuvasz Maremma Ovcharka Shar Planinetz Slovak Cuvac Tatra Sheepdog

Don't buy a herding breed such as Australian shepherd or border collie to guard your goats; they aren't qualified. Their job is to herd, and you may have a problem with them chasing goats. That isn't to say that some haven't been successful, just that they are unlikely to do a good job protecting goats.

Donkeys have been used for hundreds of years to guard sheep and other herd animals. They're very intelligent and have good hearing and eyesight. They work better alone and don't like dogs, so they can't work as a team with an LGD. Donkeys' dislike of dogs also makes them effective against coyotes. Because donkeys are naturally herd animals, if they're bonded to the goats, they can be counted on to stay with them most of the time. Ideally, you get a guardian donkey at birth or as soon as it's weaned to make sure it bonds with the goats. Because they eat the same food as the goats, donkeys also will want to stay with the herd after they realize that's where the food is.

When a guardian donkey becomes aware of a predator, she situates herself between the intruder and the herd and brays loudly. If the animal doesn't leave, she chases it, and if that doesn't work, she attacks by rearing up on her hind legs and coming down on the predator with her front feet.

Llamas and alpacas are good guardian animals because they bond quickly to goats and also eat the same feed. Castrated males make the best goat guardians. Males can injure goats by trying to mount them and can be too aggressive toward humans as well. Unlike dogs, llamas work better as guardians when they're alone instead of in a pack. A llama and guard dog combination can be trained to work cooperatively, though. Llamas need strong fences to help them do the job. If a guardian llama can't scare off a dog or coyote with his aggressive attitude, the predator may kill him.

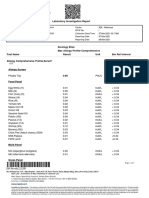

Here are the common vaccines for goats:

Goat Vaccinations

Vaccine CDT Disease Protected Against Enterotoxemia and Tetanus When to Give Does: Fourth month of pregnancy Kids: 1 month old and one month later All: Booster annually

Pneumonia

Pasteurella multocida or Mannheimia Haemolytica pneumonia Cornybacterium pseudotuberculosis

Two doses 24 weeks apart

CLA

Kids: 6 months old, 3 weeks later and annual booster Annually First 2845 days of pregnancy Annually

Rabies Chlamydia Soremouth

Rabies Chlamydia abortion Orf

All goat vaccines are formulated to be and so must be given as injections. Follow these guidelines when giving a vaccination:

To minimize the chance of an adverse reaction, vaccinate goats only when they are in good health. Do not use expired or cloudy vaccines. Use a 20-gauge, 1-inch or 3/4-inch needle on an adult, or a 1/2-inch needle on a kid. Follow the manufacturer's instructions for dosage. Use a new, sterile needle and syringe on each goat. Do not mix vaccines. For the best effect, do not delay booster shots. Keep a record of vaccinations given.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Nursing Care Plans - Nursing Dia - Gulanick, MegDokument1.374 SeitenNursing Care Plans - Nursing Dia - Gulanick, Megeric parl91% (22)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- NUR194 ADokument15 SeitenNUR194 AJemuel DalanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- HEPADNAVIRIDAEDokument14 SeitenHEPADNAVIRIDAEnur qistina humaira zulkarshamsiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Pa Tas Database (Conso)Dokument40 SeitenPa Tas Database (Conso)AlbeldaArnaldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Rizal in Ateneo de Manila and USTDokument8 SeitenRizal in Ateneo de Manila and USTDodoy Garry MitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- PreparateDokument2 SeitenPreparateVasile LozinschiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- 01-2020 - Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC)Dokument5 Seiten01-2020 - Tactical Emergency Casualty Care (TECC)pibulinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Laboratory Investigation ReportDokument7 SeitenLaboratory Investigation ReportAmarjeetNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- CEO COO Behavioral Health in ST Louis MO Resume David LeeDokument2 SeitenCEO COO Behavioral Health in ST Louis MO Resume David LeeDavidLee2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Practice TestDokument2 SeitenPractice TestMinh Châu NguyễnNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Test Bank For Phlebotomy 4th Edition by Warekois DownloadDokument9 SeitenTest Bank For Phlebotomy 4th Edition by Warekois Downloadryanparker18011988fno100% (23)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Aga Khan University Postgraduate Medical Education (Pgme) Induction Frequently Asked QuestionsDokument15 SeitenAga Khan University Postgraduate Medical Education (Pgme) Induction Frequently Asked QuestionsRamzan BibiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Ethnomedicine and Drug Discovery PDFDokument2 SeitenEthnomedicine and Drug Discovery PDFJohn0% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- United General Hospital ICU Expansion Case StudyDokument7 SeitenUnited General Hospital ICU Expansion Case StudyTeddy Les Holladayz25% (4)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- PARM LBP CPG 2nd Edition 2017 PDFDokument293 SeitenPARM LBP CPG 2nd Edition 2017 PDFGumDropNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluid Therapy and Shock: An Integrative Literature Review: Joana Silva, Luís Gonçalves and Patrícia Pontífice SousaDokument6 SeitenFluid Therapy and Shock: An Integrative Literature Review: Joana Silva, Luís Gonçalves and Patrícia Pontífice Sousateguh sulistiyantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Jurnal Kesehatan Dr. SoebandiDokument6 SeitenJurnal Kesehatan Dr. SoebandiHary BudiartoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists Final Fellowship Examination March/May 2006 Examiners ReportDokument10 SeitenThe Hong Kong College of Anaesthesiologists Final Fellowship Examination March/May 2006 Examiners ReportJane KoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Placenta PreviaDokument12 SeitenPlacenta Previapatriciagchiu100% (3)

- Dr. Manella Joseph Senior Lecturer/Consultant PathologistDokument41 SeitenDr. Manella Joseph Senior Lecturer/Consultant PathologistNipun Shamika100% (1)

- Chapter 1 Introduction To Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics 1Dokument92 SeitenChapter 1 Introduction To Biopharmaceutics and Pharmacokinetics 1Marc Alamo100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- DNRDokument1 SeiteDNRabiangdanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Participant Final Exam Answer Sheet: Emergency First Response Primary Care (CPR)Dokument2 SeitenParticipant Final Exam Answer Sheet: Emergency First Response Primary Care (CPR)Zirak Maan HussamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unik Group-1Dokument10 SeitenUnik Group-1Different PointNoch keine Bewertungen

- Farmasy Farmakoekonomi S1 2021Dokument67 SeitenFarmasy Farmakoekonomi S1 2021MochamadIqbalJaelani100% (1)

- Rachael Stanton Resume Rachael Stanton LVT 1 2Dokument2 SeitenRachael Stanton Resume Rachael Stanton LVT 1 2api-686124613Noch keine Bewertungen

- Corticosteroids 24613Dokument33 SeitenCorticosteroids 24613NOorulain HyderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Las - Mapeh - Health Module 1Dokument5 SeitenLas - Mapeh - Health Module 1Analiza SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Piis1036731421001144 PDFDokument7 SeitenPiis1036731421001144 PDFvaloranthakam10Noch keine Bewertungen

- Our Lady of Fatima University College of Nursing - Cabanatuan CityDokument3 SeitenOur Lady of Fatima University College of Nursing - Cabanatuan CityDanica FrancoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)