Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Mutual Fund Risk & Return

Hochgeladen von

pmanish1203Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mutual Fund Risk & Return

Hochgeladen von

pmanish1203Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Limited

A summer training report on

“the knowledge of Risk Tolerance that an Investor can handle

to find an optimal trade-off between the risk and returns”

(05 May 2008 – 05 Juy 2008)

Under the Guidance of

Mr. TARUN KUMAR SINGH Mr. PRASHANT DUTTA GUPTA

(INDUSTRY GUIDE) (FACULTY GUIDE)

By

MANISH PRASAD

Roll no: 27090

Batch: 2007-09

NIILM CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

NEW DELHI.

2

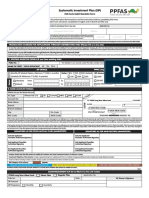

INFORMATION SHEET

1) NAME OF THE COMPANY: Mahindra & Mahindra Financial

Services Limited

2) ADDRESS OF THE COMPANY: M-8, 2nd Floor, Old DLF Colony,

Sector-14, GURGAON-121003

3) PHONE NUMBER OF THE COMPANY: 022- 66526000

4) DATE OF INTERNSHIP COMMENCEMENT: 05/05/2008

5) DATE OF INTERNSHIP COMPLETETION: 50/07/2008

6) SIGATURE AND NAME OF THE INDUSTRY GUIDE: -------------------------

Mr. TARUN KUMAR SINGH

7) DESIGNATION OF THE INDUSTRY GUIDE: “Customer Relationship manager”

8) STUDENT’S NAME: Manish Prasad

9) STUDENT’S ROLL NUMBER: 27090

10) STUDENT’S EMAIL ID: pmanish2001@gmail.com

11) STUDENT’S MOBILE/RESIDENCE NUMBERS: 9871936904/03412240836

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

3

CERTIFICATE OF AUTHENTICITY

This is to certify that MR. MANISH PRASAD student of PGDBM (Full Time) 2007-

2009 batch, NIILM – Centre for Management Studies, NEW DELHI, has done his

training project under my supervision and guidance.

During his project he was found to be very sincere and attentive to small details

whatsoever was told to him.

I wish him good luck and success in his future

…………………………… ……………………………

(Manish Prasad) ( Mr. Prashant Dutta Gupta)

27090 Professor

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

4

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

It is a pleasure to acknowledge my mentors, friends and respondents, though it is still

inadequate appreciation for their contribution.

I would not have completed this journey without the help, guidance and

support of certain people who acted as guides, friends and torchbearers along the

way.

I would like to express my deepest and sincere thanks to my company guide

Mr. Tarun Kumar Singh , Customer Relationship manager, Ashutosh pankaj of

Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Limited. and my faculty guide Mr.

Prashant Dutta Gupta for their valuable guidance and help. The project could not be

complete without their support and guidance. Thanking them is only a small gesture

for the generosity shown.

I am also thankful to all my friends, my family and all the staff members of

Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Limited , for cooperating with me at every

stage of the project. They acted as a continuous source of inspiration and

motivated me throughout the duration of the project helping me a lot in

completing this project.

Manish Prasad

27090

Niilm-Cms

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

5

ABSTRACT

A Mutual Fund is the most suitable investment for the common man as it offers an

opportunity to invest in a diversified, professionally managed basket of securities at a

relatively low cost.

In finance theory, investment risk is considered a precise, abstract and purely technical

statistical concept. This risk concept, however, does not reflect private investors’

understanding of risk; they have a more intuitive, less quantitative, rather emotionally

driven risk perception. Empirical studies that deal with investors’ risk perceptions

detect four different dimensions of perceived risk:

— Downside risk: the perceived risk of suffering financial losses due to negative

deviations of returns, starting from an individual reference point

— Upside risk: the perceived chance of realising higher-than-average returns,

starting from an individual reference point

— Volatility: the perceived fluctuations of returns over time

Ambiguity: a subjective feeling of uncertainty due to lack of information and lack of

competence.

Consumers wishing to avoid risk do not buy mutual funds, since risk is inherent in all

stock market products. Consumers may however try to minimize risks.

Consumers take a big risk when they invest money in the stock market as opposed to

traditional bank deposits or bonds. Consequently, they are willing to take that risk to

get a higher return than they would get from traditional savings.

Since no prior Consumer Behaviour studies with a holistic focus on the mutual

fund market were available, all Likert-scales had to be developed for this study.

Most consumers buy mutual funds as a means to some other goal (retirement, house,

vacation, etc.). Thus, they do not consume mutual funds in the same sense that other

products and services are consumed.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

6

CONTENTS

Information Sheet…………………………………………………………………………….2

Acknowledgement …………………………………………………………………………. 4

Abstract…………...………………………………………………………………………….. 5

Chapter 1 Introduction 7

About Mutual Fund Industry 8

About Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Limited 14

Chapter 2 Review of Literature 17

Advertising in the mutual fund business 18

Risk- Return Perceptions and Advertising Content 20

Consumer Knowledge, Involvement, and Risk Willingness on Investments 24

Return and Risk on Common Stocks 33

Idiosyncratic Risk and Mutual Fund Return 36

Chapter 3 Methodology 38

BETA, Risk and Mutual Funds 46

Data: NAVs of mutual fund schemes 53

Fund analysis 59

Chapter 4 Research Analysis and Conclusion 79

Bibliography 84

References

Annexure

-Questionnaire

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

7

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

8

ABOUT MUTUAL FUND INDUSTRY

CONCEPT

A Mutual Fund is a trust that pools the savings of a number of investors who share a

common financial goal. The money thus collected is then invested in capital market

instruments such as shares, debentures and other securities. The income earned

through these investments and the capital appreciation realised are shared by its unit

holders in proportion to the number of units owned by them. Thus a Mutual Fund is

the most suitable investment for the common man as it offers an opportunity to invest

in a diversified, professionally managed basket of securities at a relatively low cost.

The flow chart below describes broadly the working of a mutual fund:

Fig. Mutual Fund Operation Flow Chart

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

9

ORGANISATION OF A MUTUAL FUND

There are many entities involved and the diagram below illustrates the organisational

set up of a mutual fund:

Fig. Organisation of a Mutual Fund

ADVANTAGES OF MUTUAL FUNDS

The advantages of investing in a Mutual Fund are:

Professional Management

Diversification

Convenient Administration

Return Potential

Low Costs

Liquidity

Transparency

Flexibility

Choice of schemes

Tax benefits

Well regulated

TYPES OF MUTUAL FUND SCHEMES

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

10

Wide variety of Mutual Fund Schemes exists to cater to the needs such as financial

position, risk tolerance and return expectations etc. The table below gives an overview

into the existing types of schemes in the Industry.

History of the Indian Mutual Fund Industry

The mutual fund industry in India started in 1963 with the formation of Unit Trust of

India, at the initiative of the Government of India and Reserve Bank the. The history

of mutual funds in India can be broadly divided into four distinct phases

First Phase – 1964-87

Unit Trust of India (UTI) was established on 1963 by an Act of Parliament. It was set

up by the Reserve Bank of India and functioned under the Regulatory and

administrative control of the Reserve Bank of India. In 1978 UTI was de-linked from

the RBI and the Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI) took over the

regulatory and administrative control in place of RBI. The first scheme launched by

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

11

UTI was Unit Scheme 1964. At the end of 1988 UTI had Rs.6,700 crores of assets

under management.

Second Phase – 1987-1993 (Entry of Public Sector Funds)

1987 marked the entry of non- UTI, public sector mutual funds set up by public sector

banks and Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) and General Insurance

Corporation of India (GIC). SBI Mutual Fund was the first non- UTI Mutual Fund

established in June 1987 followed by Canbank Mutual Fund (Dec 87), Punjab

National Bank Mutual Fund (Aug 89), Indian Bank Mutual Fund (Nov 89), Bank of

India (Jun 90), Bank of Baroda Mutual Fund (Oct 92). LIC established its mutual

fund in June 1989 while GIC had set up its mutual fund in December 1990.

At the end of 1993, the mutual fund industry had assets under management of

Rs.47,004 crores.

Third Phase – 1993-2003 (Entry of Private Sector Funds)

With the entry of private sector funds in 1993, a new era started in the Indian mutual

fund industry, giving the Indian investors a wider choice of fund families. Also, 1993

was the year in which the first Mutual Fund Regulations came into being, under

which all mutual funds, except UTI were to be registered and governed. The erstwhile

Kothari Pioneer (now merged with Franklin Templeton) was the first private sector

mutual fund registered in July 1993.

The 1993 SEBI (Mutual Fund) Regulations were substituted by a more

comprehensive and revised Mutual Fund Regulations in 1996. The industry now

functions under the SEBI (Mutual Fund) Regulations 1996.

The number of mutual fund houses went on increasing, with many foreign mutual

funds setting up funds in India and also the industry has witnessed several mergers

and acquisitions. As at the end of January 2003, there were 33 mutual funds with total

assets of Rs. 1,21,805 crores. The Unit Trust of India with Rs.44,541 crores of assets

under management was way ahead of other mutual funds.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

12

Fourth Phase – since February 2003

In February 2003, following the repeal of the Unit Trust of India Act 1963 UTI was

bifurcated into two separate entities. One is the Specified Undertaking of the Unit

Trust of India with assets under management of Rs.29,835 crores as at the end of

January 2003, representing broadly, the assets of US 64 scheme, assured return and

certain other schemes. The Specified Undertaking of Unit Trust of India, functioning

under an administrator and under the rules framed by Government of India and does

not come under the purview of the Mutual Fund Regulations.

The second is the UTI Mutual Fund Ltd, sponsored by SBI, PNB, BOB and LIC. It is

registered with SEBI and functions under the Mutual Fund Regulations. With the

bifurcation of the erstwhile UTI which had in March 2000 more than Rs.76,000 crores

of assets under management and with the setting up of a UTI Mutual Fund,

conforming to the SEBI Mutual Fund Regulations, and with recent mergers taking

place among different private sector funds, the mutual fund industry has entered its

current phase of consolidation and growth.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

13

The graph indicates the growth of assets over the years.

GROWTH IN ASSETS UNDER MANAGEMENT

Note:

Erstwhile UTI was bifurcated into UTI Mutual Fund and the Specified Undertaking of the

Unit Trust of India effective from February 2003. The Assets under management of the

Specified Undertaking of the Unit Trust of India has therefore been excluded from the total

assets of the industry as a whole from February 2003 onwards.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

14

ABOUT MAHINDRA & MAHINDRA FINANCIAL SERVICES

LIMITED

Investment Advisory Services

Company Profile

Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Limited, a subsidiary of Mahindra &

Mahindra Limited, was established in the year 1991 with a vision to become the

number one semi-urban and rural Finance Company. In a short span of 12 years, it has

become one of the India’s leading non-banking finance company providing finance

for acquisition of utility vehicles, tractors and cars. It has more than 350 branches

covering the entire India and services over 6,00,000 customer contracts.

It is a part of US $3 bln Mahindra Group, which is among the top 10 industrial houses

in India. Mahindra & Mahindra is the only Indian company among the top five tractor

manufacturers in the world and is the market leader in multi-utility vehicles in India.

The Group is celebrating its 60th anniversary in 2005-06. It has a leading presence in

key sectors of the Indian economy, including trade and financial services (Mahindra

Intertrade, Mahindra & Mahindra Financial Services Ltd.), automotive components,

information technology & telecom (Tech Mahindra, Bristlecone), and infrastructure

development (Mahindra GESCO, Mahindra Holidays & Resorts India Ltd., Mahindra

World City). With around 60 years of manufacturing experience, the Mahindra Group

has built a strong base in technology, engineering, marketing and distribution. The

Group employs around 30,000 people and has eight state-of-the-art manufacturing

facilities in India spread over 500,000 square meters.

Mutual Fund Distribution

Recently it has received the necessary permission from Reserve Bank of India (RBI)

to start the distribution of Mutual Fund products through its network. Hitherto the

company was only participating in the liability requirements of its customers and with

mutual fund distribution business, it can also participate in their asset allocation.

When it comes to investing everyone has unique needs based on their own objective

and risk profile. Even though many investment avenues such as fixed deposit, bonds

etc. exists, equities typically outperform these investments, over a longer period of

time. We are of the opinion that, systematic investment in equity will allow you to

create Wealth.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

15

Hence only through proper allocation of your portfolio, you can get the maximum

return with moderate risk. Investing in equity is not as straight forward as investing in

bonds or bank deposits. It requires expertise and time. Our Investment Advisory

services will help you to invest your money in equity through different Mutual Fund

Schemes. For instance there are some products of Mutual Fund, which allows you to

manage your cash flow by providing liquidity (liquid Funds) as well give you tax free

return.

Personalized Service

We believe in providing a personalized service enabling individual attention to

achieve your investment goal.

Professional Advice

We provide professional advice on equity and debt portfolio with an objective to

provide consistent long-term return while taking calculated market risk. Our approach

helps you to build a proper mix of portfolio, not just to promote one individual

product. Hence your long term objective are best served.

Long-term Relationship

We believe steady wealth creation requires long-term vision, it can’t be achieved in a

short span of time. To achieve this one needs to take advantage of short-term market

opportunity while not loosing sight of long term objective. Hence we partner all our

clients in their objective of achieving their long-term Vision.

Access to Research Reports

Through us, you will have access to certain research work of CRISIL, so that you will

benefit from the expert knowledge of economists and analysts of one of the leading

financial research and rating company of India. This third party research gives you a

comfort of getting unbiased advice to make a proper decision for your investment.

Transparency & Confidentiality

Through email you will get a regular portfolio statement from us. You will also be

given a web access to view at your convenience the details of your investments and its

performance. Access to your portfolio is restricted to you and our monitoring system

enables us to detect any unauthorized access to your investments.

Flexibility

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

16

To facilitate smooth dealing and consistent attention, all our clients will be serviced

by their respective relationship executive. This allows us to provide tailor made

advice to achieve your investment objective.

Hassle Free Investment

Our relationship person will provide you with a customized service at your

convenience. We take care of all the administrative aspects of your investments

including submission of application forms to fund houses along with monthly

reporting on overall state of your investments and performance of your portfolio.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

17

CHAPTER2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

18

Advertising in the mutual fund business and the role of judgmental heuristics in

private investors’ evaluation of risk and return

Effective advertising strategies are of growing importance in the mutual fund industry

due to keen competition and changes in market structure. But the dominant variables in

financial decision making, investor’s perceived investment risk and expected return,

have not yet been analysed in an advertising context, although these product- related

evaluations can be influenced by advertising and therefore serve as additional

indicators of advertising effectiveness. In this study, I have used a large-scale

experimental study (n=100) to detect how risk-return assessments of private investors

are influenced by specific elements of print ads. In this context, judgmental heuristics

used systematically by private investors play a crucial role.

Advertising in the Mutual Fund Industry

After 2003, the mutual fund industry was one of the fastest growing market sectors in

India. Assets held in mutual funds rose from less than Rs 2000 crores at the beginning

of the decade to Rs 87,000 crores by the end of 2003. Due to fierce competition

resulting from the internationalisation of financial markets, technological changes and

fundamental changes in private households’ investment behaviour, effective

marketing strategies are of great importance in the mutual fund business, and

advertising has become an important marketing instrument to attract fund sales.

Accordingly, advertising expenditures of mutual fund companies increased

significantly in the last years. In Germany, they rose to 145.61m in 2001, which is

more than twice as high as three years before (66.75m).

Similar developments can be found in other European countries and in the USA. But

what is known about the way advertising works in the mutual fund business? There is

no doubt that many theoretical and empirical findings of behavioural advertising

research apply to investment products too, for instance the attainment of brand

awareness or the creation of emotional experiences through advertising. There are,

however, special features of investment products which advertising research should

analyse explicitly. Above all, investment decisions are characterised by high

exogenous uncertainty, as future product performance must be estimated from a set of

noisy and vague variables. So investors’ expectations about uncertain future events

play a crucial role in investment decision making. Most importantly, purchase

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

19

decisions in investment markets follow two dominant criteria: perceived investment

risk and expected return, constructs which apply exclusively to investment products.

Risk and return are crucial variables in financial decision making, as indicated in the

fundamental normative model of investment behaviour, the mean-variance portfolio

analysis. Financial services advertising should aim to influence positively investors’

perceptions of these product-specific decision criteria. This paper delivers theoretical

and empirical insights into the influence of advertising on private investors’ risk-

return perceptions. Hypotheses are tested by means of a large-scale experimental

study, and practical implications are deduced in the last section of the paper. product-

specific variables of advertising effectiveness in order to understand and optimise

advertising’s persuasive impact in this special business.

In finance theory, investment risk is considered a precise, abstract and purely technical

statistical concept. This risk concept, however, does not reflect private investors’

understanding of risk; they have a more intuitive, less quantitative, rather emotionally

driven risk perception. Empirical studies that deal with investors’ risk perceptions

detect four different dimensions of perceived risk:

— Downside risk: the perceived risk of suffering financial losses due to negative

deviations of returns, starting from an individual reference point

— Upside risk: the perceived chance of realising higher-than-average returns,

starting from an individual reference point

— Volatility: the perceived fluctuations of returns over time

— Ambiguity: a subjective feeling of uncertainty due to lack of information and

lack of competence.

These different aspects have to be taken into account, as single item measures lead to

an incomplete and simplified measurement of the perceived risk construct.Expected

return, on the other hand, is a simpler, one-dimensional numerical construct, which

can be measured in absolute or relative terms.

Effects

Risk perception and return estimations are crucial constructs in the context of

financial decision making. Traditional behavioural advertising research, however,

focuses on rather general categories of advertising effects, like awareness, recall or

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

20

attitude change. Regarding investment products, private investors’ risk-return

perceptions should be treated as additional, in intuitively quantitative evaluations.

The Relevence of Private Investors’ Judgmental Heuristics for Risk- Return

Perceptions and Advertising Content

Behavioural finance, a field of research at the interface of economics, finance and

psychology, is a relatively new paradigm and was developed in the late 1980s in the

USA due to mounting empirical evidence that existing financial theories appeared to

be deficient in a real market setting. Contrary to the normative approach of classical

portfolio theory, behavioural finance deals with the descriptive analysis of actual

behaviour of individuals in financial markets and analyses psychological influences on

information processing and financial decision making. The typical investor is

considered to be a ‘homo heuristics’ rather than a ‘homo economicus’ who makes use

of judgmental heuristics in information processing and decision making instead of

formal statistical analysis. Judgmental heuristics are abridged, often sub-optimal

information processing strategies, so-called ‘mental shortcuts’ or ‘rules of thumb’

which are used systematically but often unconsciously to simplify decision making.

Heuristics like the anchoring heuristic, the representativeness heuristic, the

availability heuristic or framing lead tobiases in the perception of risks and returns.

So if advertising content evokes the use of judgmental heuristics, advertising will

influence investors’ risk- return perceptions by means of those heuristics.

In the next sections, Explanation about two cognitive heuristics and one affect-based

heuristic and deduction of the implications for advertising effects are given. The

heuristics were chosen on the basis of their practical relevance in actual mutual fund

advertising.

Anchoring heuristic

While making forecasts, predictions or probability assessments like risk-return

evaluations of mutual funds, people tend to rely on a numerical anchor value which is

explicitly or implicitly presented to them. Anchoring effects are not restricted to

numerical values with a logical coherence to the subsequent numeric estimate.

According to the so- called ‘basic anchoring effects any random and uninformative

starting point might represent an initial anchor value which leads to biases in forecasts

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

21

and estimates of the value of that initial starting point. Anchoring effects have been

identified in many empirical studies and in various decision fields. This robust

judgmental heuristic is of particular relevance in financial markets, where it applies to

any financial forecast (eg stock market prices), leading to severe biases. In practice,

numerical data play an important role in the informative content of mutual fund ads.

Almost every print ad and many television spots highlight figures like past

performance data, assets under management, distribution of dividends etc. In addition

to direct anchor values (these are anchors that evoke direct associations with risks and

returns, eg ‘10 per cent’), indirect anchor values with dimensions other than return or

monetary units, eg ‘15,000 research specialists worldwide’, ‘Value Basket Fund’,

‘1,000 dreams come true’) can also exert an influence on estimates. In accordance

with the anchoring heuristic, even those irrelevant figures will distort return-

perceptions of the anchor value when they are prominently highlighted in the ad.

H1: A low anchor value in an ad will lead to a lower return estimation, compared to a

high anchor value, even when the anchor is uninformative in nature.

Representativeness heuristic People tend to rely on stereotypes. They judge the

likelihood of an event in accordance to its fitting into a previously established schema

or mental model. They consistently judge the event that seems to be the more

representative to be the more likely, without considering the prior probability, or base-

rate frequency of the outcomes. Representativeness is a commonly used and very

problematic heuristic in financial markets, as it leads to a misinterpretation of

empirical or causal coherence. Illusory correlation, betting on trends, naı¨ve causality,

misperception of randomness and other related biases in the use of judgment criteria

are typical consequences. For instance, past performance data and trend patterns of

mutual funds’ performance charts are extrapolated into the future without considering

the exogenous uncertainty and randomness of financial markets. In terms of practice,

mutual fund ads suggestively promote stereotype thinking by communicating positive

past performance data, fund ratings and fund awards, and by pointing out specific

brand values like trustworthiness, competence and experience. Due to stereotypical

thinking (thinking in brand associations and brand schemata), risk-return perceptions

of private investors will heavily depend on the investment company that stands behind

the investment product. With regard to investment products, however, investors’

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

22

reliance on brand images or brand stereotypes in the evaluation of risks and returns is

a severe anomaly, as strong brands cannot serve as a warranty for high returns or low

risks due to the exogenous uncertainty of financial markets.

H2: A well-known investment company with a clearly positive brand image will

evoke better risk-return perceptions at the product level compared to a relatively

unknown investment company lacking a clear and positive brand image profile,

although identical products are advertised and identical product information is

provided affect heuristic

Modern financial theory increasingly recognises the fact that financial decision

making is also determined by affective states. Negative emotions like fear, worry,

anger or shame, and positively experienced emotions like hope, greed, pleasure and

joy may influence risk-return perceptions and investment behaviour. A direct influence

of emotions on risk perception and expected returns can be deduced from the ‘affect

heuristic’ which postulates that perceptions of risks and benefits of an alternative are

derived from global affective evaluations and associations. If a stimulus arouses a

positive affective impression, the decision maker will judge the risks related to this

alternative to be lower and the benefits (eg returns) to be higher, compared to neutral

emotional states. If a stimulus is associated with negative affective impressions, the

opposite effect will occur: risks are judged to be higher, the returns, on the other hand,

to be lower. In practice, mutual fund ads most often contain emotional pictures and

emotional slogans as well as product information. In terms of the affect heuristic,

these emotional elements exert a direct influence on investors’ risk-return perceptions

if they succeed in evoking positive affective impressions of the mutual fund.

H3: If the emotional content in the ad (pictures, slogans, tonality) succeeds in evoking

positive affective impressions of the advertised mutual fund, the investor will judge

the investment risk to be lower and the return to be higher than a purely informative

ad.

The moderating impact of private investors’ expertise

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

23

It is important to discuss possible moderating factors in the use of heuristics.

Do only inexperienced, uninformed investors use these heuristics,

or are they also applied by novice and expert investors?

The question whether or not knowledge has an influence on heuristic information

processing has been controversially discussed. Some researchers underline the

unconsciousness and automatism of judgmental heuristics, implying that both lay and

expert investors systematically make use of them. Indeed, some empirical findings

reveal that investors’ expertise has no influence on the use of judgmental heuristics.

Others, however, demonstrate the moderating role of individuals’ knowledge, stating

that knowledgeable persons do not apply judgmental heuristics, or only to a moderate

extent.

Discussion

Advertising in the mutual fund industry may become more effective if advertising

firms are aware of and apply theoretical and empirical insights of behavioural

finance theory, especially regarding investors’ systematic use of judgmental

heuristics in the evaluation of risk and return. Besides more general variables of

advertising effects, it is reasonable to consider private investors’ risk-return

perceptions as additional, product-specific variables of advertising effects in the

mutual fund industry in order to understand and optimise advertising effectiveness.

Private investors make use of judgmental heuristics during the processing of

advertising stimuli, regardless of their expertise in investment decisions.

Uninformed investors, however, make use of heuristics to a larger extent, resulting

in larger biases in the perception of risks and returns. This finding highlights the

necessity of target group- or market segment-specific advertising strategies in the

investment industry, as differences in knowledge and experiences lead to different

risk-return perceptions. Numerical values in print ads serve as anchor values and

bias expected returns, even when there is no logical connection between anchor

value and return estimation. Therefore, prominent numbers and figures in mutual

fund ads have to be integrated very carefully, with full awareness of their potential

biasing influence.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

24

Brand awareness and brand image play a central role in the processing of ads, as they

are able to distort private investors’ risk perception at the product level. Investment

risk is judged lower if a highly reputable and well-known investment company offers

the advertised mutual fund. As a consequence, investing in brand equity is very

important. Private investors’ risk perceptions are influenced by emotional states.

Emotional stimuli in the ad not only lead to a more favourable, positive affective

evaluation of the advertised mutual fund, but also to a lower perception of investment

risk compared to a merely informative advertising style. This finding indicates that

emotional advertising is an effective tool, even in the abstract, rational, risk- return-

oriented investment industry.

The Impact of Consumer Knowledge, Involvement, and Risk Willingness on

Return on Investments in Mutual Funds and Stocks

Consumer knowledge, involvement, and risk are central concepts in consumer

behav- ior research. A review of prior research shows however that there is

no universally agreed understanding of how these concepts should be defined, nor

on how they are related in terms of antecedents, dimensions, and consequences. In

this study the relationship between these key concepts were explored and their

impact on consumers’ return on investments in mutual funds was analyzed.

Theory based alternative relationships were systematically tested in SEM

analyses. The study sheds new light on the knowledge concept by showing

that the knowledge construct should be modeled in terms of three dimensions

(ability, opportunity, and familiarity) in complex decision contexts (mutual funds

and stocks). The hypothesized importance of domain specific knowledge was

confirmed and a mediation analysis showed the relations of involvement and risk

willingness to knowledge and returns. Consumers’ ability and opportunity to get

access to stock market information is strongly related to their involvement, which

in turn influence both familiarity and risk willingness. Risk willingness has a

stronger effect on return than does familiarity.

In the last decade, almost all employed consumers have, intentionally or unin-

tentionally changed from being savers to being investors on the stock market.

Whereas 50% of consumers in most industrialized countries own mutual funds,

the figure can be higher for indirectly own mutual funds within a pension

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

25

system. Sweden, as an example, has a record number of indirect investors (more than

90% of the population 18–74 years old). In the trade press as well as in peer reviewed

journals (e.g., Capon et al., 1996) the growth of the mutual fund industry has been

described as a revolution; ‘In fact, it’s no overstatement to suggest that this

movement from Wall Street to Main Street is one of the most

significant socioeconomic trends of the past few decades’ (Serwer, 1999). These

consumers make risky decisions involving large amounts of money. To make

wise financial decisions, they must be able to determine how much information is

needed, which information is most useful and what sequence of information

acquisition is best for them (Jacoby et al., 2001). Their ability, motivation and

opportunity to do so influence what return they may expect on their investments.

But the overwhelming amount of technical stock market information makes it

impossible for consumers to evaluate the quality of the mutual funds on the market

(e.g., Sandler, 2002; Aldridge, 1998). The situation on the stock market is, thus,

typically a situation where many consumers would use heuristics in quality

assessments (Dawar and Parker, 1994) they

1) have a need to reduce the perceived risk of purchase;

2) they lack expertise and consequently the ability to assess quality;

3) their involvement is low (e.g., Benartzi and Thaler, 1999; Foxall and

Pallister, 1998);

4) objective quality is too complex to assess or they are not in the habit of spending

time objectively assessing quality; and

5) there is a need for information.

While heuristics may serve a purpose in many other situations of less complexity,

they may be dangerous to use on the stock market. Therefore, it does not

come as a surprise that consumers who use heuristics to make complex financial

decisions are described as naıve (Capon et al., 1996) and that they are regarded to be

in an unusually weak position on the financial market (e.g., Sandler, 2002). The

fact that shopping for financial instruments increasingly has become like

shopping for many other consumer items (Wilcox, 2001) and with entrepreneurs

like Virgin entering the market, consumers may not realize the risks of making

bad investment decisions. However, the long-term negative consumer welfare

implications from poor investments have been estimated to be in the hundreds of

thousands of dollars for individual consumer investors (Lichtenstein et al.,

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

26

1999). That will have a large impact on their future welfare. Extensive prior

research of behavioral data shows that there are two types of nonprofessional

investors, namely sophisticated and unsophisticated investors. Unsophisticated

investors (the majority) direct their money to funds based on advertising and

advice from brokers (Gruber, 1996), and their involvement is low (Foxall and

Pallister, 1998). The current practice in mutual fund advertising is to emphasize

past performance and advertised funds attract significantly more money than

comparable funds that are not advertised (Jain and Shuang Wu, 2000). Past

performance is however not associated with future results (ibid.), which may explain

why unsophisticated investors get lower return on investments.

This brief review indicates that there are certain key variables that need to be

considered in an holistic study. Prior research (e.g., Alba and Hutchinson,

1987; Lichtenstein et al., 1999; Jacoby et al., 2001) emphasizes the important

role of consumer knowledge. The effects of knowledge on consumer behavior can

however not be regarded only as main effets, but must be studied along with a wide

range of moderating variables (Alba and Hutchinson, 1987). Within consumer

behavior (CB) involvement is assumed to influence subsequent consumer behaviors

(e.g., Alba and Hutchinson, 1987; Zaichkowsky, 1985a, 1985b, 1986, 1994; Laurent

and Kapferer, 1985; Dholakia, 2001). The cornerstone principle in traditional

finance is that expected return on investments in stocks is positively related to

willingness to take risks (Shefrin, 2001), and most research on mutual funds has

employed these two explanatory variables, i.e., risk and return (Capon et al., 1996).

Harry M. Markowitz, Nobel Laureate in Economic Sciences 1990, has argued that

investors can not expect a higher return than for example the bank interest rate if they

are not willing to take risks (Bernhardson, 2004).

The aim of this study is to explore and clarify the relationships among the

key constructs and to develop a parsimonious model that captures the

relative importance of these constructs on return on investments in mutual

funds and stocks (MF&S). Earlier research on knowledge, involvement and risk has

focused on perceptual variables only, not on what matters most to consumers and

firms alike; actual behavior and the consequences of behavior. This has

hampered the cumulation of knowledge about relationships between important

constructs in CB. Comparing and contrasting mental phenomena with actual

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

27

behavior has special research benefits (Mick, 2003). Poiesz and de Bont (1995)

concluded for example that there is a lack of conceptual clarity, a seemingly

uncontrolled application, an overlap with presumed antecedents, and an

unavoidable lack of consistent operationalisa- tions of the involvement concept.

Similarly, Dholakia (1997) concluded that there is confusion in the literature whether

perceived risk should be treated as an antecedent of involvement, one of its

dimensions, or as its consequence. Laurent and Kapferer (1985) regarded perceived

risk (i.e., risk avoidance and negative consequences) as an antecedent of situational

involvement, whereas Venkatraman (1989) and Dholakia (2001) suggested that

enduring involvement precedes risk. None of them discussed situations where

consumers are willing to take risks (e.g., investments in mutual funds). Diacon

and Ennew (2001) who studied risk perceptions of UK investors included

(poor) knowledge as a dimension of risk perception rather than treating

knowledge as a separate construct. Researchers who have studied consumers

with high versus low knowledge have done so with no regard to the involvement

studies. No research has simultaneously compared the relative influence of these

three important constructs on behavioral intentions or behavior, which is similar

to the situation that prevailed in service marketing regarding the role of quality,

value, and satisfaction on behavioral intentions (e.g., Cronin et al., 2000).

There is also a general lack of contributions from the academic world in this

important domain (complex decisions or savings in MF&S) that can have

a tremendous impact on consumers’ welfare (Bazerman, 2001; Lehmann, 1999;

Lichtenstein et al., 1999; Mick, 2003). In the present study, therefore,

we systematically examined a variety of relations between the relevant key

constructs (knowledge, involvement, risk willingness, and return). Even though

the literature suggests various relations between these constructs, the guidance is

not strong enough to formulate a specific model. Therefore, the modeling task

corresponds to what Jo¨reskog (1993: 295) calls the Model Generating

(MG) situation. The alternative links between concepts in the alternative models

tested were derived from previous literature. We used a nationally representative

sample of owners of MF&S.

In terms of methodology we focused more on generalizability than on precision and

realism. Conceptually, the focus was more on parsimony than on differentiation of

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

28

detail or on the scope of the focal problem (Brinberg and McGrath, 1985: 43). These

choices seemed quite natural considering the importance of mutual funds to

most consumers, the lack of earlier research in the field, and the need

to use a representative sample to get enough variety in the answers. To summarize,

this study will clarify relations between knowledge, involvement and risk, and it will

estimate their impact on consumers’ return on investment in MF&S.

The report is organized in the following way. First, earlier research on the key

constructs is reviewed. Then the analyzed alternative models derived from the

literature are described. Third, results from the analyses of the alternative

models are presented in the following sequence: the knowledge construct,

alternative relations between knowledge and involvement, and alternative

relations between knowledge, involvement, risk willingness and return on

MF&S investments. Fourth, results are evaluated and interpreted and the

limitations of the study are acknowledged.

Theoretical Background

Consumer Knowledge

In a classic study of consumer knowledge Alba and Hutchinson (1987) made a

fundamental distinction between two major components of knowledge: expertise and

familiarity. Expertise has been defined as ‘knowledge about a particular

domain, understanding of domain problems, and skill about solving some of these

problems’ (Hayes-Roth et al., 1983: 4). It is difficult to be an expert on the stock

market. Earlier research compiled from different sources (Jacoby et al., 2001)

indicates that general market and industrywide factors (e.g., deregulation of an

industry) account for perhaps 40%–50% of the changes in a stock’s price,

approximately 300 fundamental factors (those involving a company’s financial

statement) account for approximately 30%–35% of the variance, and that other

company-unique non-financial variables (e.g., changes in leadership) account

for 20%–25% of the variance. It is, consequently, almost an understatement

to say that financial decision-making is a complex and multifaceted task. An

American survey showed for example that 66% of mutual fund investors could not

confidently name a single company in which their mutual funds invest (from

Krumsiek, 1997). The majority, 58%, of the respondents (employees at USC) in

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

29

Benartzi and Thaler’s (1999) study spent an hour or less on their retirement allocation

decision, and they read only the material provided by the vendors and consulted only

family members. Nonetheless they expressed confidence that they had made the right

choice and many of them never changed their initial choice. Against this

background it may come as no surprise that large groups of consumers both in

the US and in Europe are classified as financially illiterate. That is considered a major

problem in many countries (Aldridge, 1998; Nefe, 2002; Sandler, 2002).

Earlier research has found systematic differences between better and poorer

performers (professional analysts) in regard to the type of information access

(the content of the search), the order in which different items of information are

accessed (the sequence of the search) and the amount of information accessed (the

depth of the search) (Jacoby et al., 2001). Better performers engage in

significantly greater amounts of within-factor search. They select one factor, such as

earnings per share, and check its value for all stocks of interest before moving

on to the next factor. Poorer performers tend to do more ‘within-stock’ search. They

select one stock and check its value on all factors of interst. The better-performing

analysts tend to access more information overall and maintain the same relatively high

level of information search across all four periods of the task, while the poorer

performers typically taper off their search considerably after the first period.

Similar results were found by Hershey and Walsh (2000–2001). They found that

experts are more goal-oriented and efficient and are able to impose a

meaningful structure on ill-structured tasks and focus their attention on a

smaller number of more diagnostic items of information. The prior knowledge

of the range of acceptable parameters for a variety of variables allows experts to form

a general impression of whether an investment is indicated or not, and on that

basis they are able to specify a reasonably accurate intuitively based investment

amount. Novices are more likely to sample the opinions

of others and to use ‘nonfunctional’ attributes such as brand name and price.

In extreme cases, they may rely primarily on brand familiarity. As novices gain some

familiarity with the problem domain they simplify their solutions, whereas experts

continue to solve the problems at a consistent level of complexity across trials.

Familiarity was defined as the number of product-related experiences that have

been accumulated by the consumer (Alba and Hutchinson, 1987). Experience gives a

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

30

feeling of security and consequently a higher propensity to accept risks. When

decision-makers see themselves as more competent and knowledgeable, they are

more likely to see chance events as controllable and believe that they have

skills enough to predict events on the market (Langer, 1983). That feeling

(confidence knowledge) makes them more prone to attempt to master their

environment. Antonides and Van Der Saar (1990) found for example that the

perceived risk of an investment is lower the more the stock price has increased

recently.

Involvement

Consumers’ (enduring) involvement was defined as the on-going mobilization of

behavioral resources for the achievement of a personally relevant goal (as opposed to

Poiesz and de Bont, 1995, who discussed momentary mobilization).

Involvement was seen as the consequence of the combined subjective

assessments of motiva- tion, ability and opportunity to seek, access, interpret

and evaluate task-relevant information. As noted by Petty and Cacioppo (1981: 23,

emphasis added), ‘the level of involvement is not the only determinant of the route to

persuasion. In addition to having the necessary motivation to think about issue-

relevant argumentation, the message recipient must also have the ability to process

the message if change via the central route is to occur’. Opportunity was in their

definition subsumed under ability. This implies that high personal relevance may

be associated with low involvement, and that involvement may be considered a

determinant or antecedent to behavioral phenomena (Poiesz and de Bont, 1995).

Most consumer researchers (e.g., Laurent and Kapferer, 1985; Zaichkowsky,

1985a, 1985b, 1986, 1994) have focused on the motivational aspects of

involvement only and not on the behavioral aspects of it. Furthermore, most consumer

behaviour (CB) research on involvement deals with familiar search products rather

than with complex credence products. That difference may explain why earlier

CB research has not included ability and opportunity when defining involvement.

As noted by Poiesz and de Bont (1995: 450), ‘to the extent that ability and

opportunity conditions become more favorable, the difference between personal

relevance and involvement becomes smaller’. This study deals with a domain

where the ability and opportunity conditions are highly unfavorable.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

31

Risk Willingness

As noted by Dholakia (2001: 1342), ‘an important property of risk conceptualization

within consumer psychology is that risk is thought to arise only from

potentially negative outcomes, in contrast to other disciplines such as behavioral

decision theory and other areas of psychology, where both positive and negative

aspects are considered when evaluating risk’. Research on risk avoidance is of

limited relevance in this study. Consumers wishing to avoid risk do not buy mutual

funds, since risk is inherent in all stock market products. Consumers may however try

to minimize risks. Venkatraman (1989) as well as Dholakia (2001) suggested that

since enduring involvement is a long-term product concern while perceived risk

is limited to the purchase situation, enduring involvement precedes risk. In this

study it was assumed that perceived risk willingness is an enduring phenomenon

which lasts as long as you own mutual funds. It is extremely hard for people to think

about uncertainty, probabability, and risk (Slovic, 1984). Repeated demonstrations

have shown that most people lack an adequate understanding of probability

and risk concepts (Shanteau, 1992). Furthermore, there is no universally

agreed understanding of how risk should be conceptualized or measured (Diacon

and Ennew, 2001). But, it is generally agreed that the stock market is driven by

expectations about future returns and by risk perceptions, where psychological

risks may dominate over simple facts. Most people’s beliefs are biased in the

direction of optimism, and they also underestimate the likelihood of poor outcomes

over which they have no control (Kahneman and Riepe, 1998). Empirical studies

have shown that consumers often claim that they ‘take calculated risks’, but

that they ‘do not gamble’ (De Bondt, 1998). Many households are however

underdiversified, and do not define risk at portfolio level but rather at the level of

individual assets. In these contexts, risk is seen as controllable. Based on a review

of prior studies Diacon (2004: 182) concluded that ‘risks are perceived as being

more severe if an individual has little information or control over what may happen’.

Risk taking in a bull (hausse) market may create an illusion of control, i.e., an

expectancy of a personal success probability inappropriately higher than the

objective probability would warrant (Langer, 1983: 62). This may be explained

by the fact that consumers lack appropriate reference points (Lichtenstein et

al., 1999).

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

32

Financial Returns

Consumers take a big risk when they invest money in the stock market as opposed to

traditional bank deposits or bonds. Consequently, they are willing to take that risk to

get a higher return than they would get from traditional savings. There is no earlier

CB research on the return concept, but the success of advertising campaigns focusing

on past returns indicates that consumers are prone to listen to the high return

argument. Such advertising is one of the most important sources of information for

individual fund investors when making investment decisions (Capon et al.,

1996; Fondbolagens Fo¨rening, 2004). The content in fund advertisements

includes information on past returns and independent research (e.g., Morningstar),

whereas measures of costs and risks are absent (Jones and Smythe, 2003).

Analyzed Models

It is well known in the trade that the majority of consumers are reluctant to

buy complex financial products, and that they, in many cases, must be sold to buy

the product. It is therefore reasonable to assume that consumers must have a

minimum amount of motivation, ability and opportunity to get access to

and process information about the stock market. Without motivation, one

does not acquire expertise in such a complex domain. By adopting the definition of

involvement in the stock market used by Petty and Cacioppo (1981) as well as by

Poiesz and de Bont (1995) it follows that involvement is a consequence of

expertise. Furthermore, in this particular domain, it would be unlikely to find

consumers with expertise and involvement who do not use their knowledge for

investment purposes, i.e., thereby getting familiarity. Familiarity, in turn, may create

an illusion of control and con- sequently a higher willingness to take risks. Risk

willingness may therefore be seen as a consequence of involvement via

familiarity. However, there may be alternative models that would describe

relations between constructs in a more accurate way. Unfortunately, as already

mentioned, no previous research has simultaneously compared the relative

influence of three of the major constructs in this study, namely knowledge (expertise

and familiarity), involvement and risk (neither risk willingness nor risk avoidance)

on behavioral consequences. Earlier studies have, as mentioned, focused on the

perceptual concepts only. That explains the contradictory findings that for example

Poiesz and de Bont (1995) discussed regarding antecedents, dimensions, and

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

33

consequences of the involvement concept. It was therefore considered essential to

test alternative models to improve our understanding of the relations between

these concepts.

The first alternative was to treat knowledge as a one-factor model rather than as a

two factor-model (expertise and familiarity) as suggested by Alba and Hutchinson

(1987). In a preliminary study Zaichkowsky (1985b) emphasized that

expertise should be separated from familiarity (product use), but she studied search

products rather than complex credence products.

A second alternative is that involvement precedes knowledge rather than the

other way around as in the proposed model. The involvement literature on search

products would favor this alternative. Zaichkowsky (1985) also found that

involvement and product use (familiarity) may be related, while involvement and

expertise may not necessarily be related.

These two alternative models were also tested. Return on investments in

MF&S is the dependent variable and risk and return are related. Alternative

relations for the risk willingness concept were also tested.

Return and Risk on Common Stocks

The capital asset pricing model (CAPM) of Sharpe (1964) and others

suggests that the total risk of an asset can be dissected into a market related

component or systematic risk, and a company specific component or idiosyncratic

risk. Idiosyncratic risk can be diversified away by investors and is therefore not

priced in an efficient capital market. Systematic risk, measured by the asset s beta,

is therefore the only relevant measure of risk in an informationally efficient

market. Accordingly, in an efficient market, the CAPM predicts a linear

relation between security returns and beta.

As predicted by the CAPM, several studies using sample periods prior

to 1969 find significant linearity between beta and stock returns (Miller and

Scholes, 1972; Black, Jensen, and Scholes, 1972; Fama and MacBeth,

1973).Miller and Scholes (1972) find a linear association between average

returns and beta, as well as a positive association between average returns and

idiosyncratic risk, using a 1954 to 1963 sample period. In line with other previous

studies, which they report, they find that the relation between idiosyncratic

risk and average returns is even stronger than between beta and average returns.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

34

They also find a linear relation between beta and idiosyncratic risk. Black, Jensen,

and Scholes (1972) report a positive linear relation between average returns and

beta and demonstrate that the relation between average returns and beta for 17

non-overlapping two year periods, from 1932 to 1965, is unstable and negative for

at least 7 of the 17 periods. Finally, Fama and MacBeth (1973) find a linear relation

between average returns and beta from January 1926 to June 1968, and find that no

measure of risk besides beta systematically affects expected returns.

Recent studies are not supportive of linearity between beta and security

returns. Fama and French (1992) find that, controlling for firm size, stock beta is

not linearly related to average returns from 1963 to 1990.1 Their results are

supported by Malkiel and Xu (1997), who suggest that firm size is a better proxy of

risk than stock beta. Furthermore, Malkiel and Xu (2002) find that beta estimated

using the market model is important in explaining cross-sectional return

differences from 1935 to 1968, but that beta s role weakened considerably

during the more recent 1963 to 2000 period.2 Idiosyncratic risk, on the other

hand, is important in both periods whether it is measured using the market

model or the Fama and French (1992) three-factor model.

The relation between average returns and such firm characteristics as

size, price-to- earnings (P/E) ratio and price-to-book (P/B) ratio are well

documented. For example, Banz (1981) finds that firm size varies negatively

with average returns.3 Basu (1983), on the other hand, demonstrates that P/E ratio

varies negatively with average returns even after controlling for the effect of firm size.

Furthermore, Rosenberg, Reid and Lanstein (1985) find that P/B ratio varies

negatively with average returns, and Fama and French (1992) find a strong

univariate relation between average returns and both firm size and P/B ratio. Using a

bivariate regression, Fama and French (1992) show that firm size and P/B ratio

together absorb the role of P/E ratio in stock returns. They argue that stock

risks are multidimensional, one dimensionof risk proxied by firm size and another

proxied by P/B ratio. Moreover, Malkiel and Xu (1997) report that both firm size and

P/B ratio appear to be good proxies of risk over the 1963 to 1994 sample period.

Is Idiosyncratic Risk Relevant?

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

35

Studies that find significant association between idiosyncratic volatility and

stock returns include Miller and Scholes (1972), Friend, Westerfield, and

Granito (1978), Levy (1978), Amihud and Mendelson (1989) and Lehman

(1990). In line with Miller and Scholes (1972), Malkiel and Xu (1997) find a

significant linear relation between idiosyncratic risk and average returns. Their

results indicate that the relation between idiosyncratic risk and average returns is

even stronger than between firm size and returns. Malkiel and Xu also find a

negative relation between idiosyncratic risk and firm size and suggest that

idiosyncratic risk is a proxy for firm size and is perhaps a proxy for a wide range of

systematic factors. They argue that idiosyncratic risk may serve as a useful risk

proxy since portfolio managers are often called upon to explain why they invest in a

stock that declined considerably during a reporting period. Accordingly, such

portfolio managers may demand a risk premium on individual stocks with high

perceived idiosyncratic risk.

Noting that a significant proportion of investors are either not able or not willing to

hold the market portfolio, Malkiel and Xu (2002) contend that idiosyncratic risk could

be priced to compensate investors who are not fully diversified. Malkiel and Xu

(2002) show that idiosyncratic volatility is more powerful than either beta or

firm size in explaining the cross- sectional differences in stock returns. They

show also that the explanatory power of idiosyncratic volatility is not

subsumed by either firm size or P/B ratio. Furthermore, Goyal and Santa-Clara

(2003) show that lagged average stock variance, which they find to be mostly driven

by idiosyncratic volatility, is positively related to returns on the market. They find

this relation to be stronger for smaller firms after controlling for the effect of P/B

ratio.Campbell, Lettau, Malkiel and Xu (2001) find that idiosyncratic volatility

is the largest component of the total volatility of an average firm from1962 to

1997. They also find a significant positive trend in idiosyncratic volatility and

find no significant trend in market volatility during that period. They

demonstrate that the increase in idiosyncratic volatility from1962 to 1997 has

increased the number of randomly selected stocks needed to achieve a relatively

complete diversification. For example, 20 stocks reduced annual excess standard

deviation to 5% from 1963 to 1985, whereas 50 stocks were required to achieve the

same level of diversification from 1986 to 1997.

Idiosyncratic Risk and Mutual Fund Return

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

36

The purpose of the present study is to find out if previous evidence regarding

the relation between common stock return and idiosyncratic risk can be generalized to

mutual fund prices. A secondary objective is to investigate the relation between

mutual fund return and price-to-book (P/B) ratio, price-to-earnings (P/E)

ratio, price-to-cash-flow(P/C)ratio, and market capitalization of the

companies held by mutual funds. According to the CAPM, there should be no

significant linear relation between return and idiosyncratic volatility. There should

also be no linear relation between return and such firm characteristics as P/B ratio,

P/E ratio, P/C ratio and market capitalization unless such characteristics are proxies of

systematic risk. However, since previous studies of common stock return find positive

relation between idiosyncratic volatility and return, as discussed above, I predict

a positive relation between mutual fund return and undiversified-idiosyncratic

volatility. I also predict a negative relation between mutual fund return and P/B

ratio, P/C ratio, P/E ratio, and the capitalization of companies held by mutual funds.

Moreover, I predict positive relation between return and fund’s net assets, since

mutual fund costs are known to vary inversely with fund size.

The increase in idiosyncratic risk for individual stocks over time, the

decline in the explanatory power of the market model, and the increase in the

number of randomly selected stocks needed to achieve diversification, as

demonstrated by Campbell, Lettau, Malkiel and Xu (2001), have special

significance to institutional investors who are known to be attracted to the more

volatile stocks (Sias, 1996; Haugen, 2002). Sias observes that,

accounting for capitalization differences, larger betas and larger residual

variances are both associated with greater institutional holdings of stocks. These

findings are supported by Falkenstein (1996) who finds that mutual funds generally

prefer the larger stocks with high visibility and are averse to stocks with low

idiosyncratic risk. Falkenstein argues that mutual funds are not driven by

conventional proxies for risk and that idiosyncratic risk, rather than beta, is a

significant factor in explaining stock holdings of mutual funds. Moreover,

Lakonishok, Shleifer, and Vishny (1994) find that individuals and institutional

investors prefer stocks of glamorous firms with high P/B ratios. Furthermore,

based on Fortune Magazine’s annual survey of company reputation, Shefrin

and Statman (1995) find that financial analysts, senior corporate executives and

outside directors rank companies as if they believe that good companies are

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

37

companies with high P/B ratios, and that good stocks are stocks of well run,

highly visible companies. They also rank stocks as if they are indifferent to beta.

Consistent with the CAPM and inconsistent with several studies of stock returns, I

find no significant linear relation between mutual fund returns and undiversified-

idiosyncratic risk, even though idiosyncratic variance is approximately 45% of

the average fund s variability of returns from 1992 to 2001. Instead, the study

finds a significant nonlinear relation between returns and idiosyncratic risk.

Suggestive of economies of scale, my results show a positive linear relation

between returns and fund size after controlling for the effects of portfolio beta.

Furthermore, the study finds a negative linear relation between returns and P/B

ratio after controlling for the effects of beta, and it finds no significant linear relation

between returns and either the P/E ratio or market capitalization of companies held by

mutual funds.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

38

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

39

Methodology

Since no prior Consumer Behaviour studies with a holistic focus on the mutual

fund market were available, all Likert-scales had to be developed for this study.

Most consumers buy mutual funds as a means to some other goal (retirement, house,

vacation, etc.). Thus, they do not consume mutual funds in the same sense that other

products and services are consumed.

Expertise must be considered and accurately measured in ways that are task-

relevant (Alba and Hutchinson, 1987). In this study expertise was measured by five

variables: perception of own knowledge (subjective knowledge; SUBJ), frequency of

information search, i.e., how often the stock market was monitored (FREQ), access to

information and stock market analyses in six leading business magazines (INFO),

perceived ability to make own analyses of the stock market (EVAL), and perceived

ability to interpret annual reports (ANREP). Familiarity was operationalized as

respondents’ experience with the MF&S market in terms of own investments

and how long they had been investors. People who have invested in MF&S for

many years and who have a larger share of their savings in MF&S would by this

definition be likely to have more familiarity with the stock market. It was for example

assumed that the longer consumers have invested in the stock market, the more

tolerance they will have for the volatility in the market. Familiarity was

measured by three variables: percentage of total savings in MF&S (SAVE%), MF&S

as a percentage of annual income (INC%), and how many years the respondent

had owned MF&S (YEARS). Consumers who invest in MF&S have decided to

risk their money by investing in products that by nature are risky. Thus, they do not

avoid risk as such, although they may be more or less willing to take high risks on the

stock market. Risk Willingness was operationalized as willingness to take risks on the

stock market (RISK), feelings of uncertainty having made decisions (CERT), how

long they wait to sell a fund that decrease in value (WAIT), and what percentage of

total savings that they have in MF&S (SAVE%). The more they invest in the stock

market, the higher risk they take. SAVE% is also included in the Familiarity construct,

since a higher share of MF&S also results in a more varied experience of MF&S. The

two remaining concepts in the proposed model, enduring involvement (INVOLV),

and relative success or return on investments (RETURN) were measured by

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

40

single variables, which were used as manifest variables in the model. Enduring

involvement i.e., owners of MF&S.

Expertise must be considered and accurately measured in ways that are task-

relevant (Alba and Hutchinson, 1987). In this study expertise was measured by five

variables: perception of own knowledge (subjective knowledge; SUBJ), frequency of

information search, i.e., how often the stock market was monitored (FREQ), access to

information and stock market analyses in six leading business magazines (INFO),

perceived ability to make own analyses of the stock market (EVAL), and perceived

ability to interpret annual reports (ANREP). Familiarity was operationalized as

respondents’ experience with the MF&S market in terms of own investments

and how long they had been investors. People who have invested in MF&S for

many years and who have a larger share of their savings in MF&S would by this

definition be likely to have more familiarity with the stock market. It was for example

assumed that the longer consumers have invested in the stock market, the more

tolerance they will have for the volatility in the market. Familiarity was

measured by three variables: percentage of total savings in MF&S (SAVE%), MF&S

as a percentage of annual income (INC%), and how many years the respondent

had owned MF&S (YEARS). Consumers who invest in MF&S have decided to

risk their money by investing in products that by nature are risky. Thus, they do not

avoid risk as such, although they may be more or less willing to take high risks on the

stock market. Risk Willingness was operationalized as willingness to take risks on the

stock market (RISK), feelings of uncertainty having made decisions (CERT), how

long they wait to sell a fund that decrease in value (WAIT), and what percentage of

total savings that they have in MF&S (SAVE%). The more they invest in the stock

market, the higher risk they take. SAVE% is also included in the Familiarity construct,

since a higher share of MF&S also results in a more varied experience of MF&S. The

two remaining concepts in the proposed model, enduring involvement (INVOLV),

and relative success or return on investments (RETURN) were measured by

single variables, which were used as manifest variables in the model. Enduring

involvement exists when someone shows interest in an activity or in products over a

long period of time (Hoyer and MacInnis, 2001: 56). Consumers are motivated

to invest in MF&S for the potential returns they may get from such

investments, but the majority of them lack the ability and opportunity to

select and process the information required for making informed decisions.

NIILM- CENTRE FOR MANAGEMENT STUDIES

B-II/66, M.C.I.E., Sher Shah Suri Marg, New Delhi- 110044. Tel: (011) 29894514.

41