Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Dystopia - Usage

Hochgeladen von

maj.krzysiekOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Dystopia - Usage

Hochgeladen von

maj.krzysiekCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

86

NOTES AND QUERIES

2010

Fame is usually thought to be an ironically self-referential gesture toward Haywoods ill-fame: the scandalous reputation of her own life and work. The oppositional cast of the political wares to be had at Fame suggests an additional layer of symbolic meaning. In the vibrant, intensely visual culture of mid-century England, Fame was a stock allegorical figure who took the form of a robed and winged female bearing a trumpet with which to proclaim the triumph of virtue over corruption.14 A representation of this winged, trumpetbearing womanI reckon it to be a reproduction of the sign that hung outside Haywoods shop in Covent Gardendominates the upper third of the 1745 frontispiece to the first collected edition of Female Spectator. This framed picture of the emblematic figure of Fame floats above the lively scene of female collaborative authorship beneath that has compelled attention in our own feminist moment. The sign of Fame, present but until now unnoticed in this oft-examined frontispiece, stands a fitting reminder how much remains to be learned about this elusive author within her contemporary contexts. KATHRYN R. KING University of Montevallo

doi:10.1093/notesj/gjp251 The Author (2010). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

14 H. M. Atherton, Political Prints in the Age of Hogarth (Oxford, 1974), 28. See, e.g., To the Glory of Walpole (Plate 10) and The Noble Stand (Plate 12).

DYSTOPIA: AN EARLIER EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY USE UNTIL recently it was believed that the earliest appearance of dystopia printed as an

1 Patricia Koster, Dystopia: an Eighteenth-Century Appearance, N&Q, February (1983), 656. For the coinage of dystopia in 1868, apart from Kosters note, see Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edn) on CD-ROM. Version 3.0 (Oxford, 2002). For an update on the origin of the word, indicating its appearance in the late eighteenth century, see dystopia noun The Oxford Dictionary of English (revised edition) ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson (Oxford, 2005). Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Sofia University Library. 11 June 2009 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html? subviewMain&entryt140.e23522>.

English word was in 1782, contrary to the general understanding that it was coined by John Stuart Mill in 1868.1 According to Patricia Koster, it was Baptist Noel Turner, a lover of word-play, who coined this concept, and, as she further notices, he may be credited with the words etymology as he prefixed it with Greek letters: ty-topia.2 A recent discovery by Deirdre Ni Chuanachain, noted in Lyman Tower Sargents In Defense of Utopia, however, challenges this assertion.3 The anonymously published Utopia: or Apollos Golden Days of 1747, attributed to Lewis Henry Younge, clearly makes use of the word dystopia, though erroneously spelled, and contrasts it directly to utopia.4 In the attempt to express the opposite notion of utopia, the author of the poem, it would seem, mistakenly rendered the Greek prefix dty (in its meaning of bad or unlucky5) as dus. As a result, the newly coined word appears three times in this work as DUSTOPIA.6 My research into the appearance of the concept, however, led to a new find which proves that the use of dystopia was not an isolated case in 1747; it surprisingly emerged again in print the very next year. Extracts from Utopia, enclosed in a letter to the editor, appeared in The Gentlemans Magazine for September 1748. This time the typographically puzzling rendition of dustopia was corrected to come out as dystopia. Moreover, the excerpted version of the poem includes additional explanatory footnotes, absent in the Dublin edition of 1747, clearly defining dystopia and utopia as opposites. While it may be under dispute who corrected the prefix from dus to dysthe contributor or the editorit may be argued that the 1748 September issue of The Gentlemans Magazine printed perhaps the earliest possible spelling version of dystopia,

Downloaded from nq.oxfordjournals.org at Biblioteka Jagiellonska on January 15, 2011

Ibid., 656. Lyman Tower Sargent, In Defense of Utopia, Diogenes, liii, 1 (2006), 1117. 4 Ibid., 15. 5 Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edn) on CD-ROM. Version 3.0 (Oxford, 2002). 6 Lewis Henry Younge, Utopia: or, Apollos Golden Days (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1747), 4, 6, 21.

3

2010

NOTES AND QUERIES

87

known to the present and, very likely, shows its earliest possible definition in print. The poem praises the Earl of Chesterfields administration in Ireland and was designed as an abstract of the most remarkable passages of his excellent government.7 It allegorically envisages Ireland as dystopia before Chesterfields arrival there as lord lieutenant of Ireland: But heavn, of late, was all distraction, And, more than ever, rent in faction; Causd only by a wretched isle, On which we thought no God would smile: Not stord with wealth, nor blest in air: No useful plants would ripen there, Mismanagd by th unskilful hinds, Or nipt by chilling eastern winds: Or if they flourishd for a day, They soon became some insects prey: For many such infest the soil, Devouring th honest labrers toil; So venomous, that some had rather Have, in their stead, the toad or adder. Unhappy isle! scarce known to fame; DYSTOPIA was its slighted name. (399400) A footnote by the contributor gives a definition of dystopia which reads An unhappy country (400). This short annotation adds to a variety of meanings which the coined word may have evoked. A late seventeenth-century dictionary, for example, specifies dys as evil, difficult, or impossible;8 evil, bad, difficult, and ill, on the other hand, are used as qualifiers in dictionary definitions of scientific, predominantly medical, terms starting with this prefix.9 Obviously, dystopia benefited from these adverse notions and was coined to suggest negation in order to put a moral slant on current political affairs. Further in the poem, by the order of Jove, Apollopresumably the Earl of

Chesterfieldis sent on a mission to the unhappy country to help better its condition: Then to Apollo thus began: Haste, my beloved friend to man: Fly to yon barren, dreary shore Thou knowst my willthere needs no more. Again a God forsakes the skies, To make a sinking nation rise: But needs not study to assume A shape, as Maias son for Rome. To mortals, STANHOPE he appears, Come to dry up Dystopias tears. (400) Almost at the end of the poem, dystopia appears as diametrically opposed to utopia. In the next lines, the monarch praises Apollo for his success in inverting the state of dystopia which has finally come in agreement with British royal policy: Dystopia ownd that shaking throne, And made our royal cause her own. We, therefore, mindful of her zeal, For yours and for your monarchs weal, Sent bright APOLLO, for a while, To cheer that loyal, drooping isle! If Gratitude appears on earth, To heavn the Goddess owd her birth: Then, let her not be wholly driven To grosser earth, from purer heaven. Such bliss we never gave before: We ought no lesswe could no more. Thrice happy isle! the boast of fame, Henceforth, UTOPIA be thy name. And now, behold, he upward flies, Once more to grace his native skies. (401) In this excerpt, an explanatory footnote reference to utopia points out a happy or blessed country (401); it makes a clear contrast to the definition of dystopia, given previously on page 400. A comment in prose, intercepting the poem, regrets that the beloved and just now blessd Utopia is bewailing the absence of her tutelaries (401) and sorrowfully concludes, apparently after the Earl of Chesterfields return to England, that misrule may prevail again: Still hapless isle!how shortly blest! (402) Obviously, dystopia was coined to suggest the inverted, negative meaning of utopia in a poem

Downloaded from nq.oxfordjournals.org at Biblioteka Jagiellonska on January 15, 2011

7 Utopia, &c., The Gentlemans Magazine, xviii (Sept. 1748), 399. Subsequent references are cited parenthetically in the text. 8 Francis Gouldman, A Copious Dictionary in Three Parts (Cambridge, John Hayes, 1674). 9 Elisha Coles, An English Dictionary (1676; London, 1717). On the scientific notions of dys, see also the OED.

88

NOTES AND QUERIES

2010

praising Chesterfields administration in Ireland and warning against imminent socio-political disorder after his departure. While the contrast between dystopia and utopia can be inferred contextually from the 1747 Dublin edition, the excerpted version of Utopia: or Apollos Golden Days in The Gentlemans Magazine illustrates this opposition by means of footnoted definitions. Though it may be uncertain when exactly it was coined, apparently dystopia silently entered the public sphere in Dublin, in 1747, and in London, in 1748. The polarity between the two concepts is very much similar to J. S. Mills construal of dystopia as the opposite of utopia; yet, dystopia was coined, printed in English, and even defined as a concept much earlier than it was believed. V. M. BUDAKOV Sofia University

doi:10.1093/notesj/gjp235 The Author (2010). Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournals.org

THE MYSTERY OF ISAAC AXFORD AND HANNAH LIGHTFOOT NEITHER Mary Pendered (The Fair Quaker, 1910), nor Justinian Mallett (Princess or Pretender, 1939), nor John Lindsey (The Lovely Quaker, 1939) felt the need to reproduce in their respective books the conclusive evidence surrounding this mysterious affair that had been discovered by the founding editor of Notes & Queries. Mr W. J. Thoms had established that the Isaac Axford, who allegedly married the Fair Quaker, Hannah Lightfoot, was born at Erlestoke, Wilts. in the year 1734 (N&Q, 3rd S (285) vol. 11, 15 June 1867, p. 484); for a reader had also brought to Mr Thomss attention evidence showing that this Isaac Axford was the Isaac Axford of the same parish, described on the marriage bond as a widower, who had gone on, as legend had it, to lawfully marry Mary Bartlett, spinster of Warminster at Holy Saviours Church, Erlestoke on 3 December 1759. The reader had proof not only of the Axford/Bartlett marriage but also the baptismal certificates of both parties (N&Q,

3rd S (278) vol. 11, 1867, pp. 3423). Isaac Axfords personal history was confirmed subsequently in greater detail by Mr Horace Bleackley: the Erlestoke Registers recorded that Isaac Axford, the son of John and Elisabeth Axford, was born on 17 August 1734 (N&Q, 10th S. viii, 21 December 1907, pp. 4834). B. Wood-Holt of St John, New Brunswick, Canada, attempted in the early 1980s to construct the family tree of the Axfords of Earlestoke, Wilts, whilst omitting any mention of John and Elisabeth Axford (N&Q, vol 229, 1984, p. 397401). Sheila Mitchell and W. Ian Axford of Swindon did disprove B. WoodHolts contrasting conclusion that a William and Hester Axford were the parents of the Isaac Axford, who allegedly married Hannah Lightfoot (N&Q, vol 241, 1996, pp. 3045) whilst professing that their own scrutiny of family tradition had led them to believe that a William Axford and his wife, Susannah (Exton) were the parents. Mitchell and Axford neglected similarly the conclusive evidence provided by Messrs. Thoms and Bleackley, as did Matthew Kilburn of the New Dictionary of National Biography. Mitchell and Axfords assertion appears in the ODNB, citing an Isaac Sylvester Axford, a note of whose apprenticeship appears in the registers of the Commissioners of Stamps of Duty received on indentures, 2 June 1747: Isaac, son of William Axford was indentured for 6 years to Master John Barton, Broiderer, from Lady Day 25 March 1747. His adult baptism is assumed to have been registered in the parish of St Martin, Ludgate (Guildhall library MS 10214), 1747, May 24, Isaac Sylvester Axford, an adult person, aged 16 years. It is very apparent that two Isaac Axfords did flourish in Wiltshire and London at this particular time. Isaac Sylvester Axford was born at Xmas (?) in 1730/31 to William and Susannah Axford, and indentured to Master John Barton, Broiderer in the year 1747. Isaac Sylvester Axford had no connection with Hannah Lightfoot whatsoever. The Isaac Axford who allegedly married Hannah Lightfoot at Keiths Chapel, Mayfair on

Downloaded from nq.oxfordjournals.org at Biblioteka Jagiellonska on January 15, 2011

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Walk and Stand - Watchman NeeDokument24 SeitenWalk and Stand - Watchman NeeZafar Ismail100% (4)

- ADnDFE Oriental AdventuresDokument146 SeitenADnDFE Oriental AdventuresAlessandro Bruson100% (17)

- Pride and Prejudice-LitChartsDokument18 SeitenPride and Prejudice-LitChartsSAQIB HAYAT KHAN100% (1)

- The Player's Grimoire - Mage The AwakeningDokument35 SeitenThe Player's Grimoire - Mage The Awakeningfinnia60050% (4)

- Essentials The New Testament Greek PDFDokument288 SeitenEssentials The New Testament Greek PDFHeliana Cláudia Silva80% (5)

- Utopia Sort of A Case Study in MetamodernismDokument14 SeitenUtopia Sort of A Case Study in MetamodernismLaura DumitrescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beginning Nazarene Israelite Siddur v0.9 Home PrintableDokument35 SeitenBeginning Nazarene Israelite Siddur v0.9 Home Printablevajkember100% (2)

- The Doctrine of The Antichrist Summarized in Outline Form by Dr. John Cereghin Pastor, Grace Baptist Church of Smyrna, DelawareDokument10 SeitenThe Doctrine of The Antichrist Summarized in Outline Form by Dr. John Cereghin Pastor, Grace Baptist Church of Smyrna, DelawareChris MooreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 546 - How To Start A Prayer Ministry-From Oregon ConfDokument30 Seiten546 - How To Start A Prayer Ministry-From Oregon ConfLa Sa100% (1)

- Scottish Accent: VowelsDokument4 SeitenScottish Accent: VowelsВладислава МелешкоNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pittaway, Eileen, Bartolomei, Linda, & Hugman, Richard. Stop Stealing Our Stories.Dokument23 SeitenPittaway, Eileen, Bartolomei, Linda, & Hugman, Richard. Stop Stealing Our Stories.Gilberto Perez CamargoNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Article On EcosophyDokument21 SeitenAn Article On EcosophytathagathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedDokument21 SeitenBruno Latour - Will Non-Humans Be SavedbcmcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apocalypse-Utopia and DystopiaDokument11 SeitenApocalypse-Utopia and DystopiaMarwa GannouniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Show Us Your Papers!Dokument23 SeitenShow Us Your Papers!Timothy MortonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ecofeminism Ursula PDFDokument51 SeitenEcofeminism Ursula PDFLorena GNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Philosophical Reflection of Man in LiteratureDokument476 SeitenThe Philosophical Reflection of Man in LiteraturekrajoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elite To Inclusive. Lysistrata and Gender, Democracy, and WarDokument142 SeitenElite To Inclusive. Lysistrata and Gender, Democracy, and WarEra HeilelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authority & Utopia - Utopianism in Political ThoughtDokument21 SeitenAuthority & Utopia - Utopianism in Political ThoughtDavid LeibovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Posthumanism-Neil BadmingtonDokument5 SeitenPosthumanism-Neil BadmingtonUmut AlıntaşNoch keine Bewertungen

- On ANT and Relational Materialisms: Alan P. RudyDokument13 SeitenOn ANT and Relational Materialisms: Alan P. RudyMariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sargent - The Three Faces of Utopianism RevisitedDokument38 SeitenSargent - The Three Faces of Utopianism RevisitedFlatanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Helene Cixous: The Cat's ArrivalDokument23 SeitenHelene Cixous: The Cat's ArrivalNika Khanjani RosadiukNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frawley - Questioning The CarnivalesqueDokument9 SeitenFrawley - Questioning The CarnivalesqueAshley FrawleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Age of Living MachinesDokument2 SeitenThe Age of Living MachineskriticaosNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is BiomediaDokument33 SeitenWhat Is BiomediaNic Beuret100% (1)

- Avasthas of PlanetsDokument21 SeitenAvasthas of PlanetsJSK100% (1)

- Bakhtin and Lyric PoetryDokument21 SeitenBakhtin and Lyric PoetryGiwrgosKalogirouNoch keine Bewertungen

- Byrd-The Transit of EmpireDokument26 SeitenByrd-The Transit of EmpireEsaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Future: A New Paradigm - Pathways For Averting CollapseVon EverandThe Future: A New Paradigm - Pathways For Averting CollapseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tangled Mobilities: Places, Affects, and Personhood across Social Spheres in Asian MigrationVon EverandTangled Mobilities: Places, Affects, and Personhood across Social Spheres in Asian MigrationAsuncion Fresnoza-FlotNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Anna Greenspan) Capitalism's Transcendental Time PDFDokument225 Seiten(Anna Greenspan) Capitalism's Transcendental Time PDFAnonymous SLWWPRNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arts Education ReviewDokument298 SeitenArts Education ReviewLacrimioara Dana AmariuteiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constellations of Care: Anarcha-Feminism in PracticeVon EverandConstellations of Care: Anarcha-Feminism in PracticeCindy Barukh MilsteinBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Mimicry and Performative Negotiations of Belonging in the Everyday: A Synthesized Analysis of Maryse Condé's I, Tituba, Black Witch of SalemVon EverandMimicry and Performative Negotiations of Belonging in the Everyday: A Synthesized Analysis of Maryse Condé's I, Tituba, Black Witch of SalemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samaritan PentateuchDokument3 SeitenSamaritan PentateuchAlexandra GeorgescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- There Is No Nature and We Are Its Prophets: Timothy Morton's Ecocritical PoeticsDokument12 SeitenThere Is No Nature and We Are Its Prophets: Timothy Morton's Ecocritical PoeticsMiroslav CurcicNoch keine Bewertungen

- We Hear Only Ourselves: Utopia, Memory, and ResistanceVon EverandWe Hear Only Ourselves: Utopia, Memory, and ResistanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post Human Assemblages in Ghost in The ShellDokument21 SeitenPost Human Assemblages in Ghost in The ShellJobe MoakesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Felix Guattari Remaking Social PracticesDokument8 SeitenFelix Guattari Remaking Social Practicesvota16767% (3)

- Antonis Balasopoulos - Anti-Utopia and Dystopia - Rethinking The Generic Field PDFDokument10 SeitenAntonis Balasopoulos - Anti-Utopia and Dystopia - Rethinking The Generic Field PDFLuisa LimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Queer UtopianismDokument15 SeitenQueer Utopianismjuancr3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Situated Knowledges - Feminism and Partial Perspective - HarawayDokument26 SeitenSituated Knowledges - Feminism and Partial Perspective - HarawayGustavo Guarani KaiowáNoch keine Bewertungen

- Documentality, M. BucklandDokument6 SeitenDocumentality, M. BucklandJulio DíazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Australia as the Antipodal Utopia: European Imaginations From Antiquity to the Nineteenth CenturyVon EverandAustralia as the Antipodal Utopia: European Imaginations From Antiquity to the Nineteenth CenturyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouDokument13 SeitenAdrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouzizekNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Accidental Utopia?: Social Mobility and the Foundations of an Eglitarian Society, 18801940Von EverandAn Accidental Utopia?: Social Mobility and the Foundations of an Eglitarian Society, 18801940Noch keine Bewertungen

- Roberts Race Gender DystopiaDokument23 SeitenRoberts Race Gender DystopiaBlythe TomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eugenics and Other EvilsVon EverandEugenics and Other EvilsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Ecofeminism: A Feminist Approach To Environmental EthicsDokument6 SeitenEcofeminism: A Feminist Approach To Environmental EthicsMohammad Kaosar AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labor As Action. The Human Condition in The AnthropoceneDokument21 SeitenLabor As Action. The Human Condition in The AnthropoceneJaewon LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 20 3 HirdDokument27 Seiten20 3 HirdhawkintherainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cities of Dreams and Despair Utopia and Dystopia in Contemporary Brazilian Film and LiteratureDokument357 SeitenCities of Dreams and Despair Utopia and Dystopia in Contemporary Brazilian Film and LiteraturePedro Fortunato100% (1)

- Leonard E Read - I, Pencil (1958)Dokument18 SeitenLeonard E Read - I, Pencil (1958)Ragnar Danneskjold100% (3)

- Non-Phenomenological Thought, by Steven ShaviroDokument17 SeitenNon-Phenomenological Thought, by Steven ShavirokatjadbbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leuven University Press Transpositions: This Content Downloaded From 89.76.12.79 On Sat, 25 Apr 2020 15:16:24 UTCDokument11 SeitenLeuven University Press Transpositions: This Content Downloaded From 89.76.12.79 On Sat, 25 Apr 2020 15:16:24 UTCDaria MalickaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ellen Rooney. "A Semi-Private Room"Dokument30 SeitenEllen Rooney. "A Semi-Private Room"s0metim3sNoch keine Bewertungen

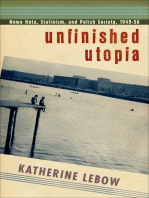

- Unfinished Utopia: Nowa Huta, Stalinism, and Polish Society, 1949–56Von EverandUnfinished Utopia: Nowa Huta, Stalinism, and Polish Society, 1949–56Noch keine Bewertungen

- De Loughrey Revisiting Tidalectics 2018Dokument6 SeitenDe Loughrey Revisiting Tidalectics 2018lonenerryNoch keine Bewertungen

- MariaImperial EyesDokument4 SeitenMariaImperial EyesEdilvan Moraes LunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ellen Rooney and Elizabeth Weed D I F F e R e N C e S in The Shadows of The Digital HumanitiesDokument173 SeitenEllen Rooney and Elizabeth Weed D I F F e R e N C e S in The Shadows of The Digital HumanitiesLove KindstrandNoch keine Bewertungen

- Williams, R. (1961 - 2006)Dokument10 SeitenWilliams, R. (1961 - 2006)Petrina HardwickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sargent, Three Faces of UtopianismDokument37 SeitenSargent, Three Faces of UtopianismJ. Jesse RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science and Sensibility: Negotiating an Ecology of PlaceVon EverandScience and Sensibility: Negotiating an Ecology of PlaceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poet Oliver Andrade PandileDokument4 SeitenPoet Oliver Andrade PandileJoan Pablo100% (2)

- Being A Widow and Other Life StoriesDokument19 SeitenBeing A Widow and Other Life StoriesWeslei Estradiote RodriguesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performance Task #4 - LyricsDokument3 SeitenPerformance Task #4 - LyricsALTHEA QUELLE MILLABASNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ishq Ka SheenDokument271 SeitenIshq Ka Sheenroadsign100% (3)

- Raymond Carver in The ViewfinderDokument21 SeitenRaymond Carver in The ViewfinderMóni ViláNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kikuchi Akane - Gambar - Pinterest: Terjemahkan Halaman IniDokument3 SeitenKikuchi Akane - Gambar - Pinterest: Terjemahkan Halaman IniFüseshü Tärürà KyòChuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legend of Lake Chini Nurul Asrina 5 ArifDokument2 SeitenLegend of Lake Chini Nurul Asrina 5 ArifCintahatiku SelamanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elizur Pinhas - ContentsDokument4 SeitenElizur Pinhas - ContentsHeloise OfParisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Michael Berg Masters PDFDokument143 SeitenMichael Berg Masters PDFCyrus ChanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cambridge Citation of SourcesDokument5 SeitenCambridge Citation of SourcesSara NamouryNoch keine Bewertungen

- SHS LiteratureDokument4 SeitenSHS LiteratureYosh CNoch keine Bewertungen

- I. Objectives: The Learners Have An Understanding of Poetry As A Genre and How To Analyze Its Elements and TechniquesDokument5 SeitenI. Objectives: The Learners Have An Understanding of Poetry As A Genre and How To Analyze Its Elements and TechniquesMary DignosNoch keine Bewertungen

- National 5 MacCaig Set Text General Revision and Set Text QuestionsDokument10 SeitenNational 5 MacCaig Set Text General Revision and Set Text QuestionsRobloxVidzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Utp MPW 2153 - Moral Studies (Assignment Format)Dokument5 SeitenUtp MPW 2153 - Moral Studies (Assignment Format)Alan A. AlexanderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Student's Friend 1 of 2Dokument28 SeitenStudent's Friend 1 of 2fwoobyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syllabus: The Documentary ImpulseDokument12 SeitenSyllabus: The Documentary ImpulseAni MaitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position StatementDokument5 SeitenPosition Statementapi-242533375Noch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Take Heed That Ye Do Not Your Alms Before Men, To Be Seen of Them: Otherwise Ye Have No Reward ofDokument8 Seiten6 Take Heed That Ye Do Not Your Alms Before Men, To Be Seen of Them: Otherwise Ye Have No Reward ofChristopher SullivanNoch keine Bewertungen