Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Mel421 Yeshaswani

Hochgeladen von

Akash MehtaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Mel421 Yeshaswani

Hochgeladen von

Akash MehtaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP IN THE PROVISION OF HEALTH CARE SERVICES TO THE POOR IN INDIA

Partnership with the burgeoning private sector has emerged as one of the avenues of health sector reforms, in many parts of the World, in part resulting from resource constraints for the public sector (Mitchell-Weaver and Manning 1992), and due to a wider belief that public sector is endemically inefficient and unresponsive and that market mechanisms will ensure cost effective, good quality services (WHO 2001; Bloom, Craig and Mitchell 2000). There is also a growing realisation that, given their respective strengths and weaknesses, neither the public sector alone nor the private sector alone would be at the best interest of the health system. It is proposed that public and private sectors in health can potentially gain from one another (ADBI 2000). Yet another perspective to private sector partnership advocates a reorientation in the role of public sector vis--vis financing and the delivery of services. Fostering a collaborative relationship with the private sector for providing health services to the poor and underserved sections of the population is particularly critical in the Indian context. Due to the deficiencies in the public sector health systems, the poor in India are forced to seek services from the private sector, under immense economic duress. Over the years the private health sector in India has grown remarkably. The private sector is not only the most unregulated sector in India, but also the most potent and untapped sector. Various state governments in India are experimenting partnerships with the private sector to reach the poor and underserved sections of the population. There are several challenges in collaborating with the private sector. The operational challenges include issues such as the motive of the partners, scope of services and objectives of partnerships, benefits to the poor and under privileged from the partnership, facilitating or constraining conditions for partnership, appropriateness of one model of partnership over the other, quality of services under partnership, technical and managerial capacity of the partners to manage a partnership, etc. Some of the policy issues relate to the risks and benefits of partnerships, institutional and legal framework, and the resource implications in such partnerships. Evidence on these issues is scanty in India. Many of the operational limitations of private partnerships are due to its nascent stage. The public sector must build technical and managerial capacity of its own institutions to optimise the benefits accruing from public private partnership. Estimates by NCAER (National Council of Applied Economic Research) show that 48% of the Indian households earn more than 90,000 (US$1,825.2) annually (or more than US$ 3 PPP per person). According to NCAER, in 2009, of the 222 million households in India, the

absolutely poor households (annual incomes below 45,000) accounted for only 15.6% of them or about 35 million (about 200 million Indians). Another 80 million households are in income levels of 45,000 90,000 per year. These numbers also are more or less in line with the latest World Bank estimates of the below-the-poverty-line households that may total about 100 million (or about 456 million individuals) and are highly dependent on free health services from the public sector. Despite having a large network of health centres and hospitals, the public sector health system is unable to deliver health care services at desirable levels of quality and efficiency due to several inherent deficiencies in the system. As a result the poor in India are forced to seek services from the private sector, often borrowing money, or selling their land, cattle and even children, to pay for the services. India has one of the highest levels of private-out of pocket- financing (to the tune of 87%) in the World (World Bank 2007). Out-of-pocket expense at the point of service use is about 84.6% (Kulkarni 2003). Such modes of financing impose debilitating effects on the poor. It is estimated that more than 40% of hospitalised people borrow money or sell assets to cover expenses, and 35% of hospitalised Indians fall below the poverty line because of hospital expenses. Out of pocket medical costs alone may push 2.2% of the population below poverty line in one year (Selvaraju and Annigeri 2001; Mahal, et al 2002). The inequities in the health system are further aggravated by the fact that public spending on health has remained stagnant at around one percent of GDP (0.9%), against the global average of 5.5%. Even the public subsidy on health does not benefit the poor. The poorest 20% of population benefit only 10% of the public (state) subsidy on health care, while richest quintile (20%) benefit to the tune of 34% of the subsidies (Mahal, et al 2002).

PRIVATE HEALTH SECTOR IN INDIA Growth of private health sector in India has been rapid. There have been several reasons for such growth: budgetary constraints leading to virtual stoppage of services in the public health facilities, government subsidies and tax incentives to the private investors setting up specialty facilities, raising middle-income groups, and unfettered regulatory environment. Estimates indicate that at independence the private sector in India had only eight per cent of health care facilities (World Bank 2004) but today it is supposedly accounts for 93% of all hospitals, 64% of beds, 80-85% of doctors, 80% of outpatients and 57% of inpatients. In financial terms, by 2012, the health care market in India would be at Rs. 1,560 billions and it is expected to reach Rs.14K billion by 2022. Apart from providing clinical services, the private sector has also gained dominant presence in all health submarkets, such as medical education and training, manufacture of medical technology and diagnostic instruments, and pharmaceuticals. Pervasiveness of the private sector portends both opportunities and challenges for the government.

In the absence of effective regulatory environment, the behavior of private health sector and its consequences is one of the most debated issues in India. Serious concerns have been expressed on several depraved practices of the private sector for pecuniary benefits. However, though private health sector is the most unregulated sector in India, it possesses immense untapped potential. Although expensive, over-indulgent in clinical procedures and without quality standards or public disclosure of practices, the private sector is perceived to be more easily accessible, better managed, and more efficient than its public counterpart. It is assumed that collaboration with the private sector in the form of Public-Private Partnership (PPP) would improve equity (by moderating the economic impact on the poor), efficiency, accountability, quality, and accessibility of the entire health system. There is also a realization that public and private sectors in health can potentially gain from one another in the form of resources, technology, knowledge and skills, cost efficiency and even their respective public image. It is also presumed that since the private sector is grossly underutilized due to its rapid, unplanned growth partnerships may actually benefit the private sector.

Several policy and plan documents on health sector in India, such as the World Bank, National Health Policy, National Commission on Macroeconomics in Health (NCMH) and Planning Commission, strongly advocated harnessing the private sectors potential and counter its failures. Simultaneously, it also proposed organizational and institutional reforms to help public sector improve its efficiency and adopt best practices from the private sector. Several state governments in India have been exploring the option of involving private sector and creating partnerships with them in order to meet the growing health care needs of the population.

PUBLIC-PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP IN HEALTH The term public and private can be defined in many ways (Wang 2000). However, in general, public sector includes organizations or institutions that function under government budgets financed by state revenue and are under direct or indirect state control. The private sector, however, is less easy to characterise. They comprise those organizations and individuals working outside the direct control of the state (Bennet 1991). Broadly, private sector includes all non-state actors, some explicitly seeking profits (for-profit) and others operating on a nonprofit (not-for-profit) basis. The former are conventionally called private enterprise; the latter as non-governmental organizations (NGOs). In health sector, the diversity in the composition of for-profit providers range from individual physicians, diagnostic centres, ambulance operators, pathology labs, pharmacy shops, blood banks, commercial contractors, polyclinics, nursing homes, hospitals of various capacities, etc. They may also include community service extension of industrial establishments, co-operative societies, community-based organizations, religious and philanthropic trusts, professional associations, self-help groups, citizen forums and other types of non-state organizations. The not-for-profit sector is also highly heterogeneous, but is significantly less in proportion. Apart from the motive, characteristics of the private sector also may vary depending on geographical location, nature of ownership and financing, system of medicine, and the scope of clinical services provided. Public Private Partnerships in health care sector in India: 1. The Uttaranchal Mobile Hospital and Research Center (UMHRC) It is three-way partnership among the Technology Information, Forecasting and Assessment Council (TIFAC), the Government of Uttaranchal and the Birla Institute of Scientific Research (BISR). The motive behind the partnership was to provide health care and diagnostic facilities to poor and rural people at their doorstep in the difficult hilly terrains. TIFAC and the State Govt. shares the funds sanctioned to BISR on anequal basis. 2. PHCs in Gumballi and Sugganahalli, Karnataka Management of Primary Health Centers in Gumballi and Sugganahalli was contracted out by the Government of Karnataka to Karuna Trust in 1996 to serve the tribal community in the hilly areas. 90% of the cost is borne by the Govt. and 10% by the trust. Karuna Trust has full responsibility for providing all personnel at the PHC and the Health Sub-centers within its jurisdiction; maintenance of all the assets at the PHC and addition of any assets if required at the PHC. The agency ensures adequate stocks of essential drugs at all times and supplies them free of cost to the patients. No patient is charged for diagnosis, drugs, treatment or anything else except in accordance with the Government policy. The staff salaries are shared between the Govt. and the Trust. Gumballi district is considered a model PHC covering the entire gamut of primary health care preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative

3. Yeshasvini Health scheme in Karnataka The Yeshasvini Co-operative Farmers Healthcare Scheme is a health insurance scheme targeted to benefit the poor. It was initiated by Narayana Hrudayalaya, superspecialty heart hospital in Bangalore, and by the Department of Co-operatives of the Government of Karnataka. The Government provides a quarter (Rs. 2.50) of the monthly premium paid by the members of the Cooperative Societies, which is Rs.10 per month. The incentive of getting treatment in a private hospital with the Government paying half of the premium attracts more members to the scheme. The cardholders could access free treatment in 160 hospitals located in all districts of the state for any medical procedure costing upto Rs. 2 lakhs. 4. Arogya Raksha Scheme in Andhra Pradesh The Government of Andhra Pradesh has initiated the Arogya Raksha Scheme in collaboration with the New India Assurance Company and with private clinics. It is an insurance scheme fully funded by the government. It provides hospitalization benefits and personal accident benefits to citizens below the poverty line who undergo sterilization for family planning from government health institutions. The government paid an insurance premium of Rs. 75 per family to the insurance company, with the expected enrollment of 200,000 acceptors in the first year.

5. Emergency Ambulance Services scheme in Tamil Nadu The Government of Tamil Nadu has initiated an Emergency Ambulance Services scheme in Theni district of Tamil Nadu in order to reduce the maternal mortality rate in its rural area. The major cause for the high MMR is an on-medical cause - the lack of adequate transport facilities to carry pregnant women to health institutions for childbirth, especially in the tribal areas. This scheme is part of the World Bank aided health system development project in Tamil Nadu. Seva Nilayam has been selected as the potential non-governmental partner in the scheme. This scheme is self-supporting through the collection of user charges. The Government supports the scheme only by supplying the vehicles.

6. Urban Slum Health Care Project, Andhra Pradesh The Urban Slum Health Care Project the Andhra Pradesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare contracts NGOs to manage health centers in the slums of Adilabad. The basic objectives of the project are to increase the availability and utilization of health and family welfare services, to build an effective referral system, to implement national health programs, and to increase health awareness and better health-seeking behaviour among slum dwellers, thus reducing morbidity and mortality among women and children. To serve 3 million people, the project has established 192 Urban Health Centers. Five Mahila Aarogya Sanghams (Womens Wee-Being Associations) were formed under each UHC, and along with the self-help groups and ICDS workers mobilize the community and adopt Behaviour Change Communication strategies. The

NGOs are contracted to manage and maintain the UHCs, and based on their performance, they are awarded with a UHC, or eliminated from the program

7. Rajiv Gandhi Super-specialty Hospital, Raichur, Karnataka The Rajiv Gandhi Super-specialty Hospital in Raichur Karnataka is a joint venture of the Government of Karnataka and the Apollo hospitals Group, with financial support from OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries). The basic reason for establishing the partnership was to give super-specialty health care at low cost to the people Below Poverty Line. The Govt. of Karnataka has provided the land, hospital building and staff quarters as well as roads, power, water and infrastructure. Apollo provided fully qualified, experienced and competent medical facilities for operating the hospital. The losses anticipated during the first three years of operation were reimbursed by the Govt. to the Apollo hospital. From the fourth year, the hospital could get a 30% of the net profit generated. When no net profit occurred, the Govt paid a service charge (of no more than 3% of gross billing) to the Apollo Hospital. Apollo is responsible for all medical, legal and statutory requirements. It pays all charges (water, telephone, electricity, power, sewage, sanitation) to the concerned authorities and is liable for penal recovery charges in case of default in payment within the prescribed periods.

8. Community Health Insurance scheme in Karnataka The Karuna Trust in collaboration with the National Health Insurance Company and the Government of Karnataka has launched a community health insurance scheme in 2001. It covers the Yelundur and Narasipuram Taluks. Underwritten by the UNDP, the Karuna Trust undertook the project to improve access to and utilization of health services, to prevent impoverishment of the rural poor due to hospitalization and health related issues, and to establish insurance coverage for out-patient care by the people themselves. The scheme is fully subsidized for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes who are below the poverty line and partially subsidized for nonSC/ST BPL. Poor patients are identified by field workers and health workers who visit door-todoor to make people aware of the scheme. ANMs and health workers visiting a village collect its insurance premiums and deposit them in the bank.

THE KARNATAKA YESHASVINI HEALTH INSURANCE SCHEME FOR RURAL FARMERS & PEASANTS Yeshasvini Cooperative Farmers Health Care Trust is a charitable trust governing a health insurance scheme of the same name. The scheme was launched at the end of 2002 and became operational in June 2003. In October 2003, the Trust was officially registered as a charitable trust. The Trust and its insurance scheme are based on the initiative of Dr. Devi Shetty, An expert in cardiac surgeries and chairman of Narayana Hrudayalaya Hospital in Bangalore. He started a telemedicine programme in cooperation with Indian Space Research Organisation (IRSO). Through this programme, medical expertise is made accessible to people even in remote rural areas of Karnataka. He spread sophisticated surgical methods in many rural areas by connecting doctors and urban hospitals via satellite. Lack of proper infrastructure was supposed to be the root of the insufficient medical treatment many people experienced. However, field studies conducted on behalf of the hospital revealed something different: a number of hospitals throughout Karnataka experienced poor utilization rates, as low as 35%. This lead to the conclusion that it was not the improper health infrastructure, but insufficient financial means that hindered the poor people from curing their health problems. To address the problem of low purchasing power, the idea of health insurance covering critical surgeries evolved, and Dr. Shetty and his team developed the insurance model of Yeshasvini. Mr. A. Ramaswamy I.A.S., then Principal Secretary in the Department of Cooperation, Government of Karnataka, then gave concrete shape to Shettys idea. Yeshasvinis goal is to provide quality health care all over the state of Karnataka at affordable prices. The target group are relatively poor farmers organised in cooperative societies. An inexpensive insurance policy, affordable even for low-income groups, is only possible if there is a sufficiently big risk pool. Farmers pay a relatively small annual premium that allows them access to high-quality treatment including critical operations. To get a sufficient number of members, some of the bigger cooperative federations like Karnataka Milk Federation, were addressed. Within the first seven months, 5,000 members underwent all different kinds of surgeries and 23,500 farmers or family members had ambulatory consultations without paying an extra fee. Starting with 1.6 million of members in the beginning, the scheme already had more than 2 million members in 2004.

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE To describe the organizational structure of Yeshasvini Cooperative Farmers Health Scheme, it is helpful to separate the full structure into four pillars: 1. The Trust 2. The Third Party Administrator (TPA) 3. The Governments Cooperative Structure 4. The Cooperative Sector 1. The Trust Yeshasvini Trust is the actual owner of its insurance scheme. It is registered as a charitable trust and governed by a board of trustees. This board consists of six persons from the Department of Cooperation, who are board members by designation, the Director of the Karnataka Health Department, and five nominated board members (mainly medical professionals). The board of the trust governs the whole scheme and is responsible for its further development, final decision on claims, reimbursing the claims, monitoring performance and listing new network hospitals. The TPA, Family Health Plan Limited (FHPL), representatives of the cooperative sector (federation level) and the network hospitals may attend the meetings as well (top line of the figure).

2. Third Party Administrator TPAs are for-profit-companies that assume most of the administration of an insurance scheme in exchange for a commission. The TPAs main duty is to manage the contact between the client, the health care provider and the insurance scheme. Yeshasvini has hired Family Health Plan Limited, a TPA registered with IRDA, to administer its scheme: FHPL has experience with selffunded schemes as it administers two schemes for the police in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh. The tasks assigned to FHPL include: a) Maintaining a register of the insured clients b) Issuing ID cards c) Authorising treatment d) Preparation of claim settlement including verification e) Managing the funds f) Monitoring the network hospitals and guide them g) Prepare reports and statistics

3. Governments Cooperative Structure The Principal Secretary of the Karnataka Department for Cooperation chairs the board of the trust. The Department for Cooperation is actively involved in distributing the insurance. The governments support of the cooperative structure helps makes the scheme as successful in reaching large numbers of insured.

4. Cooperative Sector Yeshasvini depends on this cooperative structure to provide information to members and to collect premiums. The members receive information about the scheme in their regular contact with the Secretary or President of their Cooperative Society. During the subscription period, they can join the scheme or renew their policy. The individual cooperative societies in turn receive their information from their unions. The link between the cooperative society and the union is maintained by the Extension Officer, a person employed by the union. He visits the cooperative societies in his area of responsibility on a regular basis. Informing the secretaries of the cooperative societies about insurance and collecting subscription lists and premiums is an additional task for him.

The distribution channel of work has proven to be extremely effective in reaching a huge membership quickly. This is especially true because of the targets set by the Department of Cooperation. If secretaries react to these targets by enrolling members with pressure or make enrolment compulsory, the long-term effectiveness is jeopardised, as there may be dissatisfaction among clients. Following the subscription phase, an ID card for each client has to be issued.

PREMIUM COLLECTION All households enrolled in the scheme are in a business relationship with a cooperative society. By selling goods to the cooperative society, they generate a significant proportion of their income. This income is used to pay for the premium. The process of premium collection is integrated in the members business relationship with their cooperative society. During the subscription period, the secretary of the cooperative collects the premium from the member and issues a receipt. In case members cannot pay the amount in cash, it will be deducted from the income they gain from selling goods to the cooperative society. At the end of the collection process the secretary of the cooperative (physically) hands over the premium collected to the Extension Officer, an employee of the union to which the cooperative society belongs. The premium of members who did not pay in cash is debited on the cooperative societies account at the union and deducted from payments to the society. The premium of all unions and cooperatives in a district are collected at a bank account of the office of the Deputy Registrar of Cooperative Societies who then places the money in Yeshasvinis bank account.

CLAIM MANAGEMENT In case of illness, an insured client needs to prove membership in a cooperative society before approaching a network hospital. For this purpose, the client contacts the secretary of the cooperative society for a referral letter. This referral letter is usually counter-checked and signed by the deputy manager of the responsible union and the assistant registrar of cooperative societies, both located in the capital of the district. This documentation is especially important if the member falls ill when new ID-cards are being produced. Some request a letter from the Department for Cooperation to get faster admission. With this letter, the photo ID-card and the receipt of having paid the last premium, the client chooses a network hospital for treatment where he or she registers at a special counter or with a designated person. The patient receives free OPD consultation and if necessary investigations under reduced rates. These investigations are free if the patient is admitted for surgery. If the patient needs to be admitted without surgery, he or she must pay for the hospitalization. In case surgery is needed, pre-authorization is requested from the TPA. A photocopy of the members ID card, the receipt and the referral letter are sent along with the pre-authorization form filled by the treating doctor. Receiving authorization from the TPA takes at least four to five days, and sometimes longer. Sometimes the documents submitted by the hospital are incomplete, which delays authorization further. Pre-authorizations for surgeries in emergencies ought to be given within a day orally by the medical officer of FHPL; the documents should then be sent by courier. If in emergency cases the request for authorization is pending, some hospitals charge the patients and reimburse them after receiving authorization. With the authorization obtained, the surgery is conducted free of costs for the patient. The rate for the surgery is fixed. After discharge the hospital submits the claim documents to FHPL, including further photocopies of the Yeshasvini ID card and the receipt, the original referral letter from the cooperative society, the pre-authorization form issued by FHPL, the operating notes, the discharge summary, the final bill and investigation reports as well as prescriptions. FHPL then scrutinizes the documents and settles the claim. If documents are missing, the hospital is requested to provide them before claim processing can be finalized. Processed claims are forwarded to the monthly meeting of the Board of the Trust for final approval. After approval, the claim is paid to the hospital. Reimbursing claims can take about three months. It can take more than a month from submission of the claim to FHPL, scrutinizing it, to finally presenting it at the monthly board meeting. Transfer of the money can take about a month as well. While this is no problem for large, financially solvent hospitals, it troubles some smaller, charitable ones.

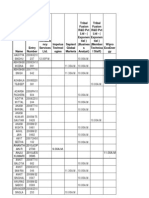

Claim Settlement Process

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- SPB Pg78-79 Prod PR CropshgfytfDokument2 SeitenSPB Pg78-79 Prod PR CropshgfytfAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comunicaciones Industriales by Luis MARTINEZ Vicente GUERRERO Ramon YUSTE and Alfaomega Grupo EditorDokument1 SeiteComunicaciones Industriales by Luis MARTINEZ Vicente GUERRERO Ramon YUSTE and Alfaomega Grupo EditorSalvador Yana RocaNoch keine Bewertungen

- India and Latin AmericaDokument4 SeitenIndia and Latin AmericaAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GS UpscDokument3 SeitenGS UpscAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vajiram 2011 Polity 1Dokument71 SeitenVajiram 2011 Polity 1Akash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comunicaciones Industriales by Luis MARTINEZ Vicente GUERRERO Ramon YUSTE and Alfaomega Grupo EditorDokument1 SeiteComunicaciones Industriales by Luis MARTINEZ Vicente GUERRERO Ramon YUSTE and Alfaomega Grupo EditorSalvador Yana RocaNoch keine Bewertungen

- JHVHGHGVDokument1 SeiteJHVHGHGVAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDokument2 SeitenNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich EngelsDokument26 SeitenThe Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich EngelsjanagarrajaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PADokument4 SeitenPAMohan MurariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poverty Ratio 2009-10Dokument1 SeitePoverty Ratio 2009-10Akash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- II Semester Courses 2011-12Dokument60 SeitenII Semester Courses 2011-12Akash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constituion of India ArticlesDokument4 SeitenConstituion of India ArticlesRaghu RamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2011 12 21 - 1Dokument8 Seiten2011 12 21 - 1Akash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Countries and CapitalsDokument4 SeitenCountries and CapitalsAkash MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rise of Indian National CongressDokument18 SeitenRise of Indian National CongressNishant Kumar100% (1)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Variable TypesDokument2 SeitenVariable Typesmarmar418Noch keine Bewertungen

- PNF PatternsDokument19 SeitenPNF PatternsDany VirgilNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 5953781827192751296Dokument119 Seiten4 5953781827192751296Ridha Afzal100% (1)

- Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics: Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics PediatricsDokument2 SeitenPediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics: Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics Pediatrics PediatricsBobet Reña100% (2)

- Assam Tea Gardens Cachar, Burtoll T.E. Commissionerate of Labour, Government of Assam Plantation Association name: TAIBVBDokument4 SeitenAssam Tea Gardens Cachar, Burtoll T.E. Commissionerate of Labour, Government of Assam Plantation Association name: TAIBVBAvijitSinharoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ISOFLURANE anaesthesia data sheetDokument5 SeitenISOFLURANE anaesthesia data sheetChristian James CamaongayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Counseling Theories Applied to JakeDokument2 SeitenCounseling Theories Applied to JakeArielle RamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glyphosate Poisoning: Presenter: Prabu Medical Officer: Dr. NG KL Specialist: DR KauthmanDokument39 SeitenGlyphosate Poisoning: Presenter: Prabu Medical Officer: Dr. NG KL Specialist: DR KauthmanPrabu PonuduraiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aiswarya Krishna: Professional SummaryDokument4 SeitenAiswarya Krishna: Professional SummaryRejoy RadhakrishnanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Janie Jacobs Resume March 2019Dokument2 SeitenJanie Jacobs Resume March 2019api-404179099Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Mitre Issue 01 Vol 01Dokument12 SeitenThe Mitre Issue 01 Vol 01Marfino Geofani WungkanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TW Case StudyDokument27 SeitenTW Case Studyapi-346311171Noch keine Bewertungen

- Biomedics Toric: Symbol DescriptionDokument2 SeitenBiomedics Toric: Symbol DescriptionHemantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers Mock Exam 1Dokument8 SeitenAnswers Mock Exam 1Amin AzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newborn Care PresentationDokument35 SeitenNewborn Care PresentationChristian PallaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aseptic Non Touch Technique - A Guide For Healthcare WorkersDokument2 SeitenAseptic Non Touch Technique - A Guide For Healthcare Workersananda apryliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review For Specimen Labeling and Blood BankDokument3 SeitenLiterature Review For Specimen Labeling and Blood Bankapi-236445988Noch keine Bewertungen

- MED 2 Electrical Safety Test of Medical Equipment After RepairDokument17 SeitenMED 2 Electrical Safety Test of Medical Equipment After RepairAfiz86Noch keine Bewertungen

- THE HR Chronicle - November'19Dokument8 SeitenTHE HR Chronicle - November'19DrSwati Jayant PawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Apply To CPA's Clinical Specialty ProgramDokument20 SeitenHow To Apply To CPA's Clinical Specialty ProgramDr Hafiz Sheraz ArshadNoch keine Bewertungen

- LeprosyDokument9 SeitenLeprosyJohn Ribu Parampil100% (1)

- Readers Digest EssayDokument15 SeitenReaders Digest EssayHaslina ZakariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parotid Tumors and Other Salivary Gland TumorsDokument41 SeitenParotid Tumors and Other Salivary Gland Tumorsdrhiwaomer100% (9)

- LCD PresentationDokument38 SeitenLCD PresentationAnaz HamzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar On BUDGETDokument14 SeitenSeminar On BUDGETprashanth60% (5)

- Code of Conduct EnglishDokument8 SeitenCode of Conduct EnglishNithya NambiarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Job Analysis Guide for Eye Care CenterDokument131 SeitenJob Analysis Guide for Eye Care CenterAnitha RajNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Shouldice Repair: Robert Bendavid, MDDokument14 SeitenThe Shouldice Repair: Robert Bendavid, MDmarquete72Noch keine Bewertungen

- Posterior Capsular OpacityDokument3 SeitenPosterior Capsular OpacityRandy FerdianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bumrungrad HospitalDokument3 SeitenBumrungrad HospitalAhmadnur kholilNoch keine Bewertungen