Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

43428696

Hochgeladen von

Mike HouriganOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

43428696

Hochgeladen von

Mike HouriganCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 37:221229, 2009 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN:

1085-2352 print=1540-7330 online DOI: 10.1080/10852350902976106

Risky Behavior: Cell Phone Use While Driving

LORI L. ORLOWSKE and PAUL D. LUYBEN

Department of Psychology, State University of New York College at Cortland, Cortland, New York, USA

In the present experiment we investigated the percentage of drivers who use cell phones while driving in a small city in central New York. We expected that the rates of cell phone use would be comparable to national levels, and that the percentage of cell phone use would be higher as the distance from the police station increased. We took observations of vehicles and drivers at three locations and on two different days of the week. One of the locations was adjacent to the police station whereas the others were located 1 and 1 miles from the police station. While the overall results were consistent with other estimates of national rates of cell phone use while driving, the differences we found between the rates at the police station and at remote locations were negligible. KEYWORDS adults, cell phone use, distraction, driving, police, risky behavior

Vehicle crashes accounted for 118 deaths per day on American highways in 2002 (Clayton, Helms, & Simpson, 2006). Contributing factors include talking, eating, attending to children, putting on make-up, retrieving lost food, reading mail or newspapers, cell phone use, and so on (Insurance Information Institute, 2007). The Insurance Information Institutes report also cited the Nationwide Mutual Insurance Companys report that 73% of drivers surveyed reported that they had talked on cell phones while driving. Among causes of crashes, The Cellular Telecommunications & Internet Association (cited in

This project was completed in partial fulfillment of the requirements of an undergraduate Psychology course taught by the second author. We recognize Joseph Tutko, who participated as the reliability observer. Address correspondence to Paul D. Luyben, PhD, BCBA, Department of Psychology, SUNY Cortland, Cortland, NY 13045, USA. E-mail: luybenp@cortland.edu 221

222

L. L. Orlowske and P. D. Luyben

Insurance Information Institute report, 2007) reported that cell phone use has dramatically increased by a factor of about five from 1990 to 2007 (to 236 million users). At any given moment in the day in 2002 it has been estimated that 3% of drivers of passenger vehicles, or 500,000 drivers, are using cell phones (Information Brief, 2002). Given the dramatic increases in cell phone use, it is likely that a greater percentage of drivers are using cell phones at the present time. Some researchers have suggested that up to 6% of drivers reported using either hand-held cell phones or hands-free devices (Parker, 2006). Research on visual inattention during driving demonstrated, at least during simulations, that the use of cell phones impaired drivers reactions to situational factors, such as lighted brake lights (Strayer, Drews, & Johnson, 2003). Other data show that cell phone use interferes with driving performance (Lissy, Cohen, Park, & Graham, 2000). The Insurance Information Institute (2007) cited a report indicating that cell phone users were four times more likely to be involved in injury-related crashes than non-cell phone users. Others have taken a balanced approach, suggesting that analyses of cell phone use need to consider both costs and benefits (Lissy et al., 2006). The purpose of this study was to compare rates of cell phone use while driving in a small city in central New York with national rates and also to determine if the percentage of use increased as the distance from the police station increased. We hypothesized that local cell phone use rates would approximate national averages and also that cell phone use rates would decline at locations nearer to the police station.

METHOD Drivers Observed and Target Behavior

The target behavior was using a cell phone while driving, operationally defined as looking at, pushing buttons, or holding a cell phone to ones ear. Because it was not possible to separate speaking or singing from talking with a hands-free device, observations were limited to those in which the drivers hands were visibly in contact with a cell phone. Vehicles selected for observation included passenger vehicles that were not clearly associated with commercial purposes and police vehicles. Excluded from the data were taxis, public bus services, vehicles advertising businesses, and vehicles with tinted windows. The rationale for observing passenger vehicles and not commercial vehicles is that commercial vehicle drivers are often required to use cell phones to contact their home bases whereas use of a cell phone is optional among private passenger vehicles. Commercial vehicles were defined as vehicles that displayed any form of advertising. We also excluded vehicles

Risky Behavior

223

with tinted windows because we could not see inside the vehicle to determine if the driver was using a cell phone.

Data Collection

Data were obtained during 15 sessions at 3 locations; the local police station and two other locations distributed on major arteries radiating from the station. The two locations were a half-mile west of the police station (Burger King), and one mile east of the police station (Honda Shop). The observers sat in cars at Burger King and Honda Shop locations and on benches outside of the local police station. We used event recording to determine the total number of cars that passed by in both directions during a 30-minute session and the number of vehicles in which the driver was observed using a cell phone. Sessions were at 9 a.m. on Mondays and 3 p.m. on Fridays to sample two different days and times of day to attempt to obtain a reasonable sample of overall rate of cell phone use. Frequency data were recorded in 2-minute blocks to facilitate reliability measures. That is, observers recorded the number of vehicles, and the number of drivers using cell phones, that passed by their locations driving in one direction in 2-minute blocks.

Reliability

Reliability was established by having a second observer simultaneously and independently record the number of vehicles in which cells phones were in use and the total number of vehicles that passed each location during each 2-minute block. An agreement was scored if the data obtained by the reliability observer was within plus or minus two occurrences in any given block. Intervals in which a discrepancy of more than two vehicles occurred were counted at disagreements. The number of agreements on intervals divided the number of agreements plus the number of disagreements on intervals 100 yielded a percentage agreement. Our reliability data ranged from 87 to 100%.

RESULTS

Figure 1 presents the overall percentage of drivers observed using cell phones across days of the study. The data show a cyclical pattern of cell phone use over time corresponding to days of the week. The first data point is a Monday, with Friday and Monday data alternating on subsequent days. That is, the relatively low data points represent Mondays and the high data points Fridays. The data show a clear and consistent pattern with lower values on Mondays than on the corresponding Fridays, although there is variability over time for both days. The data range from 1.3% to 5.1%, with a mean of 3.2% of drivers using cell phones. Further, the volume of traffic varied from day to day with the average number of vehicles observed on Mondays and Fridays at 293 and 470 vehicles, respectively.

224

L. L. Orlowske and P. D. Luyben

FIGURE 1 Overall percentage of drivers using cell phones while driving across days.

FIGURE 2 Percentage of drivers using cell phones at the Burger King (triangles), Police Station (squares), and Honda Shop (circles).

Risky Behavior

225

FIGURE 3 Average percentage of drivers using cell phones at the three locations.

Figure 2 presents the data from the three locations on one graph, showing variations between settings and across days. With one exception (day 13 at the Honda shop) these data show the same alternating pattern seen in Figure 1 with no consistent differences between sites.

FIGURE 4 Percentage of drivers using cell phones on Mondays at the Burger King (triangles), Police Station (squares), and Honda Shop (circles).

226

L. L. Orlowske and P. D. Luyben

FIGURE 5 Percentage of drivers using cell phones on Fridays at the Burger King (triangles), Police Station (squares), and Honda Shop (circles).

To compare data between sites in a simpler way, Figure 3 shows the overall means for the three sites separately and overall. The data show that there was no relationship between proximity to the police station and cell phone use. Roughly speaking, cell phone use at the police station was midway between the rates observed at the Burger King and Honda Shop. Figure 4 presents the percentage of drivers using cell phones at the three locations on Mondays. Inspection of the graph shows considerable variability across locations and days but no consistent pattern. The data across locations and days range from 1.1 to 5.3% cell phone users, with a mean across locations of 2.3%. Comparable data from Fridays are presented in Figure 5. These data show a roughly parallel and cyclical pattern at the police station and Honda Shop, a pattern that is not matched consistently at the Burger King. These data range from 2.85.8% of drivers using cell phones, with an overall mean of 4.3%.

DISCUSSION

At a little over 3% of drivers (Figure 3), the overall rate of cell phone use that we observed was consistent with national levels as of 2002 (Information Brief, 2002). Despite increases in the number of people using cells phones today compared to 2002 the rates we obtained were comparable to the earlier result. However, because of the exclusions we made (e.g., commercial vehicles,

Risky Behavior

227

vehicles with tinted windows, and hand-held devices) it is virtually certain that the actual rate of cell phone use is higher than we recorded, perhaps as high as 6% (Parker, 2006), if our assumption that commercial drivers are more likely to use cell phones than drivers in ordinary passenger vehicles is correct. Because it is illegal to operate a vehicle while using a cell phone without a hands-free device in New York State, we expected that the percentage of drivers using cell phones while driving would be inversely proportional to the distance from the police station. We supposed that the proportion of ` police vehicles vis a vis the general traffic would be higher in the vicinity of the police department, and we hypothesized that drivers would be more cautious about using cell phones when close to the police station. The data did not support this hypothesis. The location data representing the 15 days of the study (Figure 2) are consistent with the overall data, showing the same oscillation in rates on Mondays and Fridays. Data from the two remote locations were both higher and lower than the rate at the police station and the differences were small (Figure 5). These data are counterintuitive because one might assume that the threat of arrest would be higher near police stations and that compliance with the law would be greater. Other data on the effects of patrol density and patterns have shown that the effects of different approaches to police patrol have produced inconclusive effects. For example, some research shows that higher rates of patrols are associated with lower rates of crime, whereas other data indicate that whether or not reductions occur is related to the density of homes in residential neighborhoods and the time of day of the patrol (Kirchner et al., 1980; Schnelle, Kirchner, Casey, Uselton, & McNees, 1977; Schnelle et al., 1979; Schnelle et al., 1978). Our data do not bear on the relationship between the density of patrols and the rate of cell phone use, however, because even though we included police vehicles in the tally, only two observations of police vehicles were made, with one police officer using a cell phone while the other did not. The low rates of observations of police vehicles call into question the assumption that the density of police vehicles would be higher closer to the police station and precludes any inferences about the possible effects of the density of police patrols on cell phone use. It is unclear whether or not these data are representative of the day as a whole, however. It is important to note that the fact that only two observations of police patrols were made means that the primary data almost entirely reflect the behavior of drivers of passenger and commercial vehicles and therefore are not skewed by the presence of police vehicles even though the police are likely to use cell phones while on patrol. Separating the Monday data from the Friday data (Figures 4 and 5) shows differences. Although there is variability in both sets of data, there is

228

L. L. Orlowske and P. D. Luyben

a distinct oscillating pattern in the Friday data that is largely missing in the Monday data. At present we have no explanation for this discrepancy that would account for the oscillating pattern seen on Fridays. The original purpose of the study was to obtain a sampling of cell phone use across two days and two times to see if local data were representative of national data. The study was not designed to tease out reasons for differences in rates. Nevertheless, the Monday=Friday contrast shown in Figure 1 is striking. Adjusted for the number of drivers, there were fewer instances of cell phone use on Monday morning than there were on Friday afternoons, a day when there was more traffic. Observed differences could be due to the time of day, the day of the week, or to a combination of these factors. One can only speculate on the reasons for these differences. Possibly some of the Friday drivers were returning home after leaving work and were coordinating evening and weekend activities, students traveling out of town for the weekend, or other groups; whereas Monday drivers were workers on their way to work, or drivers fulfilling appointments, completing errands, or other activities. There is no way to tell from these data. These data do differ, however, from data collected by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (Parker, 2006). They observed cell phone use between the hours of 8 a.m. and 6 p.m., finding that the drivers of 6% of almost a million vehicles were using their cell phone at any moment during daylight hours (Parker, 2006). There is clearly a need to sample times more systematically in the local area to generate better estimates of cell phone use at different times of the day. Perhaps a more systematic analysis of days and times would reveal a consistent pattern that could be associated with the purpose of driving or perhaps the demographics of drivers. Knowledge of these factors is potentially important as it might lead to strategically targeted intervention strategies. Two anecdotes that occurred during and immediately after the study are relevant here. Of particularly poignant interest is the fact that during the project an unfortunate accident occurred involving an off-duty police officer and two female pedestrians. The police officer, in addition to driving under the influence of alcohol, was texting on his cell phone as he made a turn when he struck both pedestrians (Sylor, 2006). One of the women died because of her injuries while the second female underwent intensive treatment for her injuries and later died. This accident highlighted the seriousness of cell phone use while driving (as well as inebriation) and the need to develop effective interventions to decrease cell phone use while driving. It seems likely that texting may be a more serious issue than talking on a cell phone, a question that could be investigated in future studies. The second anecdote arose from students responses to the first authors presentation of these data to a college class. After describing the study and the story of the two pedestrians, the first author highlighted the importance of police enforcement of rules prohibiting cell phone use while driving. Both authors were surprised and dismayed to hear chuckles and chortles from the

Risky Behavior

229

class. It turned out that five or more students in the class had received tickets for driving while using their cell phones but reported, with laughter, that the tickets had not deterred them from using their cell phones while driving. This despite just having heard the story of the two women who had been killed and injured. (The second woman had not yet died at the time of the class.) Clearly, if society wishes to see a reduction in cell phone use while driving it will be important to evaluate the effects of the programs and to change attitudes of the public toward cell phone use and texting while driving. These anecdotes suggest that current levels of intervention may be insufficient to deter or decrease cell phone use.

REFERENCES

Clayton, M., Helms, B., & Simpson, C. (2006). Active prompting to decrease cell phone use and increase seat belt use while driving. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 39, 341349. Information Brief. (2002). Cell phones and driving. Retrieved October 19, 2007, from www.house.leg.state.mn.us/hrd/hrd.htm Insurance Information Institute. (2007). Cell phones and driving. Retrieved October 19, 2007, from www.iii.org Kirchner, R. F., Schnelle, J. F., Domash, M., Larson, L., Carr, A., & McNees, M. P. (1980). The applicability of a helicopter patrol procedure to diverse areas: A cost-benefit evaluation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 143148. Lissy, K., Cohen, J., Park, M., & Graham, J. D. (2000). Cellular phones and driving: Weighing the risks and benefits. Harvard Center for Risk Analysis, 8(6), 16. Retrieved January 10, 2008, from http://www.hcra.harvard.edu/rip/risk_in_ persp_July2000.pdf Parker, J. G. (2006). An accident waiting to happen? Cell phone use continues to increase. Family Safety & Health, 65(2), 2425. Schnelle, J. F., Kirchner, R. E., Jr., Casey, J. D., Uselton, P. H., Jr., & McNees, M. P. (1977). Patrol evaluation research: A multiple-baseline analysis of saturation police patrolling during day and night hours. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 3340. Schnelle, J. F., Kirchner, R. E., Galbaugh, F., Domash, M., Carr, A., & Larson, L. (1979). Program evaluation research: An experimental cost-effectiveness analysis of an armed robbery intervention program. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 12, 615623. Schnelle, J. F., Kirchner, R. E., Macrae, J. W., McNees, M. P., Eck, R. H., Snodgrass, S., Casey, J. D., & Uselton, P. H., Jr., (1978). Police evaluation research: An experimental and cost-benefit analysis of a helicopter patrol in a high crime area. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11, 1121. Strayer, D. L., Drews, F. A., & Johnson, W. A. (2003). Cell phone-induced failures of visual attention during simulated driving. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 9, 2332. Sylor, A. (2006). Police officer was texting before crash. Cortland Standard, 274, 12.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Intoduction To WeldingDokument334 SeitenIntoduction To WeldingAsad Bin Ala QatariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Havehas Affirm Neg Interrogwith Aliens - 19229Dokument3 SeitenHavehas Affirm Neg Interrogwith Aliens - 19229Ana Victoria Cuevas BeltránNoch keine Bewertungen

- SA 8000 Audit Check List VeeraDokument6 SeitenSA 8000 Audit Check List Veeranallasivam v92% (12)

- Energy Optimization of A Large Central Plant Chilled Water SystemDokument24 SeitenEnergy Optimization of A Large Central Plant Chilled Water Systemmuoi2002Noch keine Bewertungen

- Of Periodontal & Peri-Implant Diseases: ClassificationDokument24 SeitenOf Periodontal & Peri-Implant Diseases: ClassificationruchaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waste Heat Recovery UnitDokument15 SeitenWaste Heat Recovery UnitEDUARDONoch keine Bewertungen

- AMTA Report 2011Dokument26 SeitenAMTA Report 2011Mike HouriganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment SchoolDokument21 SeitenAssessment SchoolMike HouriganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Movement TherapyDokument5 SeitenMovement TherapyMike HouriganNoch keine Bewertungen

- Music Therapy Perspectives 2009 27, 2 Proquest Direct CompleteDokument9 SeitenMusic Therapy Perspectives 2009 27, 2 Proquest Direct CompleteMike HouriganNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Review On Bioactive Compounds of Beet Beta Vulgaris L Subsp Vulgaris With Special Emphasis On Their Beneficial Effects On Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal HealthDokument13 SeitenA Review On Bioactive Compounds of Beet Beta Vulgaris L Subsp Vulgaris With Special Emphasis On Their Beneficial Effects On Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal HealthWinda KhosasiNoch keine Bewertungen

- FSSC 22000 V6 Guidance Document Environmental MonitoringDokument10 SeitenFSSC 22000 V6 Guidance Document Environmental Monitoringjessica.ramirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beckhoff Service Tool - USB StickDokument7 SeitenBeckhoff Service Tool - USB StickGustavo VélizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Improving The Livelihoods of Smallholder Fruit Farmers in Soroti District, Teso Sub Region, Eastern Uganda RegionDokument2 SeitenImproving The Livelihoods of Smallholder Fruit Farmers in Soroti District, Teso Sub Region, Eastern Uganda RegionPatricia AngatoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal SOL MeningiomaDokument6 SeitenJurnal SOL MeningiomaConnie SianiparNoch keine Bewertungen

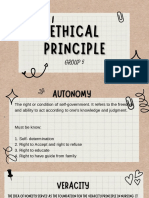

- Group 5 - Ethical PrinciplesDokument11 SeitenGroup 5 - Ethical Principlesvirgo paigeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact Behaviour of Composite MaterialsDokument6 SeitenThe Impact Behaviour of Composite MaterialsVíctor Fer100% (1)

- Unit Weight of Soil in Quezon CityDokument2 SeitenUnit Weight of Soil in Quezon CityClarence Noel CorpuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Butt Weld Cap Dimension - Penn MachineDokument1 SeiteButt Weld Cap Dimension - Penn MachineEHT pipeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Stress TheoryDokument10 SeitenFamily Stress TheoryKarina Megasari WinahyuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan PPEDokument3 SeitenLesson Plan PPEErika Jean Moyo ManzanillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Massage Therapist NtewDokument2 SeitenResume Massage Therapist NtewPartheebanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frequency Inverter: User's ManualDokument117 SeitenFrequency Inverter: User's ManualCristiano SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PV2R Series Single PumpDokument14 SeitenPV2R Series Single PumpBagus setiawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probni Test 1. Godina - Ina KlipaDokument4 SeitenProbni Test 1. Godina - Ina KlipaMickoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Buss 37 ZemaljaDokument50 SeitenBuss 37 ZemaljaOlga KovacevicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liebherr 2956 Manual de UsuarioDokument27 SeitenLiebherr 2956 Manual de UsuarioCarona FeisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Six Account Group General Fixed Assets Account Group (Gfaag)Dokument5 SeitenChapter Six Account Group General Fixed Assets Account Group (Gfaag)meseleNoch keine Bewertungen

- ClistDokument14 SeitenClistGuerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Industries Visited in Pune & LonavalaDokument13 SeitenIndustries Visited in Pune & LonavalaRohan R Tamhane100% (1)

- Menu Siklus RSDokument3 SeitenMenu Siklus RSChika VionitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Careerride Com Electrical Engineering Interview Questions AsDokument21 SeitenCareerride Com Electrical Engineering Interview Questions AsAbhayRajSinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 8 - ThermodynamicsDokument65 SeitenLecture 8 - ThermodynamicsHasmaye PintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Portraiture & Modern Spain: Dr. Rebecca M. Bender (Dokument6 SeitenLiterary Portraiture & Modern Spain: Dr. Rebecca M. Bender (Pedro PorbénNoch keine Bewertungen