Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Twilight of The Goths

Hochgeladen von

Erika GeronimoOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Twilight of The Goths

Hochgeladen von

Erika GeronimoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

EBSCO Publishing Citation Format: AMA (American Medical Assoc.): NOTE: Review the instructions at http://support.ebsco.com/help/?

int=ehost&lang=&feature_id=AMA and make any necessary corrections before using. Pay special attention to personal names, capitalization, and dates. Always consult your library resources for the exact formatting and punctuation guidelines. Reference List Porter B. Twilight of the Goths. History Today [serial online]. July 2011;61(7):10-16. Available from: Academic Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 22, 2011. <!--Additional Information: Persistent link to this record (Permalink): http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s8h&AN=63018991&site=ehost-live End of citation-->

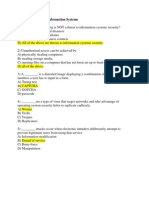

Twilight of the Goths Foreign Office A mid-Victorian competition to design new Government Offices in Whitehall fell victim to a battle between the competing styles of Gothic and Classical. The result proved unworthy of a nation then at its imperial zenith, as Bernard Porter explains The present-day Foreign and Commonwealth Office in Whitehall is one of the least distinguished and most unattractive of all London's great public buildings, certainly from the outside. There is a reason for this. It was designed by a leading architect of the mid-19th century, but in a style he had little liking for. Indeed he more or less disowned it from the moment he finished drawing up the plans. No one else at the time liked it very much either: not the prime minister, who was the one who had forced him to change his original design; nor the foreign secretary, who had to work there. In architectural circles it has had a bad press ever since. Nor has it been much of a magnet for visitors and tourists, most of whom scarcely notice it as they pass by on their way up from Westminster to Trafalgar Square, having admired the Abbey and the Houses of Parliament. In the 1960s there was even a plan for demolishing it and replacing it with something more modern. But it survived and in the 1990s the building's interior was gloriously restored (unfortunately not many people get to see the inside). But that still doesn't make it a great piece of architecture. Historians, however, are not only interested in success. Failure can sometimes tell us more. Why did the new Government Offices -- of which the Foreign Office formed just a part -- turn out to be so disappointing? It was supposed to be one of the 19th century's great national building projects, second in importance only to the recently (almost) completed Palace of Westminster. In some circles it was dubbed a 'Palace of Administration', though that term did not catch on. As such, it was hoped it would be worthy of the nation; a monument to its greatness, however that

might be defined. The basic problem was that no matter how Britain's greatness was defined, it was not thought to include the arts. Architecture in particular was widely considered to be at a low ebb in early Victorian times, despite the construction of the Palace of Westminster from 1840, which even before its completion had fallen out of favour among the cognoscenti. More typical were supposed to be the dull Classical boxes and pseudo-temples of the period, like William Wilkins' National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, which was universally derided. (Prince Charles' famous campaign in 1984 to save it from being disfigured by a modernist 'carbuncle', as if it were a masterpiece, would have raised a wry smile from contemporaries. Many of them might have welcomed a carbuncle or two.) The lack of confidence in architectural circles is highlighted by the fact that even its style could not be agreed upon. It was to the huge disadvantage of the Government Offices project, in fact, that it came bang in the middle of a full-scale 'battle', as it was called, between two historical styles for the architectural soul of the nation. The first was the familiar old Classical; the other was neo-Gothic, the fresh young Turk of a style that was supposed to sweep away the Classical dead wood and revive the architectural face of Britain. There were also squabbles within each of these camps: between 'Roman' and 'Greek' Classical, for example, and 'Decorated' and 'Perpendicular' Gothic (hence the Perpendicular Palace of Westminster's fall from grace). It was these battles that dominated the debate over the new building and explain its unfortunate outcome. The decision, taken in 1855, to build a new Foreign Office was a practical one. The old Foreign Office, originally a private house in Downing Street, was quite literally falling about its staff's ears. One story, repeated many times, told how in 1852 the Foreign Secretary, Lord Malmesbury, had narrowly escaped injury, even death, when a ceiling collapsed on the desk he had just been sitting at. It was also felt to be an embarrassment whenever foreign diplomats visited it from their own magnificent diplomatic palaces in Paris or Vienna. So a competition -- the Victorians, of course, swore by competitions -- was held to find a design, open to everyone, including foreigners. The entries, more than 200 of them, were exhibited to the public in Westminster Hall in May and June 1857. These came in a number of styles, but with a preponderance of Classical (usually French Classical), followed by Gothic. When the exhibition came to an end a committee was set up to adjudicate between the different designs and select three separate winners: tor the Foreign Office, a War Office (though that was later scrapped to make way for an India Office) and the ground plan. That was a silly idea for a start, for it was highly unlikely that any of the winning designs would fit any of the ground plans unless they were submitted by the same architect, and the rules of the competition precluded one man (all the competitors were men, incidentally) from winning in more than one category. Be that as it may, the winner for the block plan was a Frenchman, a Monsieur Crepinet; in the Foreign Office category it was an Italian-Classical design by Messrs Coe and Hofland; and in the War Office class a French-Classical design by Henry Garling. Even informed architectural historians are unlikely to recognise any of these names and with good reason: they were all very minor architects. Coe and Hofland's only previous project had been for 'an insane asylum in Ramsgate', which did not seem a very apt precedent for a Foreign Office -- or perhaps it did? Two factors came in here. The first was that the entrants were supposed to be anonymous so the judges had no idea of their reputations beforehand. The second is that the judges were all rank amateurs

apart from one, William Burn, a professional architect, though just as obscure as Coe, Hofland and Garling. Apart from David Roberts, the water-colourist, and Isambard Kingdom Brunei, the great engineer, the rest were all aristocrats, chosen for 'character' rather than expertise. Halfway through their deliberations, troubled perhaps by their ignorance, they co-opted two professional architects to advise them, though they were not given voting rights. Again, these men were not very well known (the Saturday Review called their selection 'a practical joke') and in any case they disagreed with every one of the committee's verdicts. There is no getting away from it: this must have been one of the worst-run competitions in architectural history. Whatever we feel about the Foreign Office building as it stands today we should probably be thankful that the winning design in that class was never built. This was because the competition had a 'get-out' rule, which stipulated that although the eventual architect should be chosen from among those who had won 'premiums' (there were several in each class), he did not have to be the outright winner. Among the other prize-winners there were some more competent architects: Edward Barry (1830-80), for example, son of the co-architect of the Palace of Westminster, who came second in the Foreign Office class with a Classical design; the Gothicists George Gilbert Scott (1811-78), the partnership of Deane and Woodward, and George Edmund Street (1824-81), who came third, fourth and seventh respectively in that category; and the great Yorkshire builder Cuthbert Brodrick (1821-1905), who came fifth in the War Office class with another Classical design. Of these, Scott was the most famous, partly because of the ubiquity of his work, stretching even across the Channel -- he had just won a competition to build a new Nikolaikirche in Hamburg -- and possibly because of its quality. That of course is largely a question of taste. A very pushy Victorian, he was also a crusader for Gothic. He sought to spread the style from churches and colleges -- the designs of which it had come to monopolise -- to urban secular projects. For him the new Government Offices represented the crucial battlefield in this campaign, the key fortress to conquer before marching on. It was he who emerged triumphant from the competition, outflanking the first two winners in the Foreign Office category and everyone in the War Office, to become the officially appointed architect of the whole complex. The reasons for his triumph are complicated. The most important factor was that a new government had recently come to power (Lord Derby's second administration, from February 1858 to June 1859), whose Commissioner of Works, Lord John Manners, was a dedicated Goth (he even lived in a neo-Gothic house, Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire). He swung it so that Scott got the commission, justifying it on the grounds that because Scott had come second in the Foreign Office category (if you discounted Coe and Hofland) and would have come second in the War Office category if the rules had permitted him to win two prizes, this -- his double seconds -- put him above either of the single firsts. It was a specious argument, of course (what would you say if the winner of a horse race were decided on this principle, asked Lord Palmerston). But the Goths weren't bothered. Their great cause had won. Not for long. Very soon all this unravelled. Again party politics intervened. Before Scott even had time to lay the foundations of his glorious new Gothic Government Offices, Palmerston returned as prime minister (in June 1859) and almost immediately scuppered them. Palmerston (whose own house was 'Palladian') loathed Gothic. He thought it was dark and gloomy; he associated it with medieval superstition, if not with the sack of his beloved Rome ('Goths and Vandals'; Classically educated people were often misled by the name) and he took Scott and his

fellow crusaders at their word when they claimed they were out to conquer the world for their style. He was not having any of that. His problem, however, was that Scott had already been given the commission. On the other hand he had not been promised that he could carry it out in his chosen style. That was still up to his patron, in this case Palmerston, who was answerable to Parliament. So he demanded that Scott dump his Gothic scheme and produce a new, Classical one. Scott objected, but to no avail. Then he tried to compromise with what he called a Byzantine design. Palmerston wasn't having that either: 'a regular mongrel affair', he called it; 'neither one thing nort 'other'. Most of Scott's supporters expected him to resign at this stage out of principle, which was probably what Palmerston wanted too. (He had a Classical architect, fames Pennethorne, lined up to take over.) But Scott did not resign, to the shock of his fellow Goths and to the detriment of his reputation thereafter. The present 'Italianate' building is the result. Palmerston still didn't much like it, but felt it would 'do'. In the deciding debate on July 8th, 1861, the House of Commons supported Palmerston. That was the moment of Palmerston's great victory against the Goths and it happened 150 years ago this summer -- if anyone wishes to celebrate it. We know why Scott caved. He didn't want to lose his fat fee. "The work had been mine', he later wrote in his memoirs,' and to give up what represented in the end about five and twenty thousand pounds which was placed by providence in my hands as a trustee for my family, seemed to me to be an immoral act.' Well that was one face to put on it. Others might not regard it in such moral terms and Scott himself felt twinges of guilt over it for the rest of his life. Why the House of Commons backed Palmerston against him is a little more complicated, but may be equally unprincipled. There is no evidence that MPs or the constituents they represented favoured Classical over Gothic or vice-versa. Most of them, judging from poor attendances at the debates and thin coverage in the press, had no particular preferences and very little interest in architecture at all. What they may not have liked was the seriousness, even fanaticism of the Goths, from which Palmerston's lighthearted, even buffoonish approach to the whole argument -he made the Commons laugh a lot -- was a relief. A significant number of MPs did not want a great new building at all, mainly for reasons of economy. But there was a class element involved, too: why should the taxpayer provide 'great rooms' where aristocrats could 'gossip and flirt'. Did they not have houses of their own they could use for that? And there was a further factor. The Houses of Parliament had only recently been opened to the Commons. One flaw in its design was the stuffiness of the Commons chamber, which meant that its windows had to be opened in the summer to allow air in. Unfortunately those windows overlooked the Thames, which at this period gave out an 'abominable stench' on hot days from the ordure carried there by Mr Thomas Crapper's brand-new invention, the flush toilet (contemporary architectural journals are full of advertisements for this wonder) and from the 'dead cats, dead dogs, and occasionally dead human beings' dumped in it. Many MPs, illogically, associated this with the style of that building, which of course was Gothic. As it happens, July 8th, 1861 was sweltering -- the hottest day of that month. That cannot have helped the Gothic cause. The story goes that after this disappointment, and not wanting to waste a good Gothic design, Scott tweaked it a little before plumping it down in St Pancras and calling it the Midland Railway Hotel. That building (recently renovated in spectacular style at great expense) was long the butt of jokes. In fact if we look at the two designs we can see that they were not the same. Yet Scott did intend St Pancras to be a riposte to those who, in the battle over the Foreign Office,

had claimed that the Gothic style was intrinsically unsuited to public secular buildings. A better idea of how his Gothic Foreign Office might have looked if he had been allowed to go ahead with it is furnished by a painting of the design, much revised, which he submitted to the Royal Academy in 1864, three years after the battle, as a 'silent protest against what was going on'. Some of us might think that would have been preferable to the building we have. Of course this, too, is a matter of taste; as are the virtues of one or two other alternatives mooted at the time, such as an 1844 plan by Thomas Wyatt to complete Inigo Jones' Palace of Whitehall, of which only the famous Banqueting Hall had been built originally; a dignified scheme of 1855 by James Pennethorne, the official government architect, designed on the misunderstanding that he would be the automatic choice; and a drawing of a huge, splendid and domed 'Government Palace' by Sir Charles Barry, presented to Parliament in 1857 but for some reason not entered in the competition. That British architects could design fine public buildings is also proved by much of the provincial architecture of this period such as the great city halls, law courts, corn exchanges and libraries erected in Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds, in both Classical and Gothic styles. What seems a shame is that the capital lost out on this quality and variety of buildings. One reason may be that local identities were stronger at that time than the national one: people were prouder of being Mancunians, for example, than Britons; or at least keener on celebrating this pride in stone. This applied especially when the stones were being used for a national building that was designed to rule, control, administer, tax and recruit them in order to fight foreigners, or, in the specific case of the Foreign Office, to conspire with other rulers. Unless you were one of those rulers this was hardly something to celebrate. This is what marked the 'Palace of Administration' off from the Palace of Westminster, whose rebuilding in the 1840s people had taken an interest in, representing as it did, in style and in purpose, the 'ancient liberties of the British people', usually defined at that time against their rulers. 'Administration', even when it was administering an empire, carried no such warm patriotic glow. For contemporary British architecture this must be regarded as a lost opportunity, not only because of the mediocre building that resulted, but also in the light of the discussions that had preceded it, the quality of which deserved a more serious resolution. There have been other great architectural controversies in British history, of which the latest was that between Prince Charles and Richard Rogers over the redevelopment of Chelsea barracks in 2009 (with the prince playing the Palmerston role). None, however, begins to compare with this particular 'Battle of the Styles' in range, passion and sophistication. Not that all the arguments on either side of the debate were sophisticated. One prize example, though it comes from rather later, is Sir Edwin Lutyens' objection to the pointed arch -- a prime characteristic of Gothic, though he thought he was criticising Islamic architecture -- on the grounds that 'God had not made a pointed rainbow'. In general, however, the mid-19th-century debate was better than that. The great question at issue was this: what style of architecture should be adopted by an architectural profession that was almost universally thought to have lost its way in the early 19th century, one which would reflect and be worthy of Britain as she was then? The debate was carried on in a myriad of books, pamphlets, speeches and magazine articles delving quite deeply into aesthetic questions, as we would expect, but also into the question of the relation of architecture to contemporary British society more generally. It drew on a range of contemporary discourses about, for example,

national and religious identities; race and gender; society and politics; science and technology; ethics, history and modernity. One of the most interesting aspects of the debate is how each side tried to harness the idea of 'progress' to its cause. For today's historians this provides an almost unique insight into the state of British culture at this moment, seen through the lens of this issue; not a complete one, because many of the great concerns of the day could not be refracted through this debate, but one that highlights the rich, confusing and even contradictory variety of the social and cultural milieu of the time. It was an impressive debate; but it was all wasted so far as its immediate object -- the design of the new Government Offices -- was concerned. The style that was eventually chosen owed almost nothing to it: indeed, almost none of the participants in the pamphlet and press debate recommended Italian Renaissance style for the new building. All the battle did was to sour the atmosphere in which the more specific debate about the Government Offices took place and to contribute to the fiasco that determined its upshot: a Classical building by a Gothic architect. It was exactly this sort of outcome that the original competition for designs had been supposed to prevent. Competition, in mid- 19th century liberal ideology, guaranteed excellence, yet in this case it did not. The fault for that lay partly with the botched arrangements made for this particular competition: the three categories, ignorant judges, and so on, as well as its subversion by politicians, especially Palmerston, whose insistence on his favourite style marked a return to the supposedly discredited 'patronage' system. Even Palmerston's support, however, was limited in this case to forcing an already appointed architect to re-design against his grain to the liking of neither of them. Without such constraint Palmerston would almost certainly have been able to commission a better building (Pennethorne's), just as Scott might have seen his best Gothic design (the 1864 version) made reality. What we have instead is a building that was largely an accident and from which we can therefore 'read' very little about contemporary British society: except that in the light of the early Victorians' stylistic insecurity, their general lack of interest in architecture and the absence of enthusiasm when it came to building for the capital's bureaucrats, it was probably all they deserved. For further articles on this subject, visit: www.historytoday.com/architecture Further reading Ian Toplis, The Foreign Office: An Architectural History (Continuum, 1987); David Brownlee, 'That "Regular Mongrel Affair": GG Scott's Design for the Government Offices', Architectural History, vol. 28 (1985), pp. 159-97; A. Seldon, The Foreign Office: an Illustrated History of the Place and its People (HarperCollins, 2000); Scott, George Gilbert, Personal and Professional Recollections (Sampson Lowe, 1879; 1995 reprint, Paul Watkins; edited and with an introduction by Gavin Stamp); G. Bremner, 'Nation and Empire in the Government Architecture of mid-Victorian London: the Foreign and India Office reconsidered', Historical Journal, vol. 48 no. 3 (2005), 703-42; M.H. Port, Imperial London: Civil Government Building in London, 1851 -1915 (Yale University Press, 1995); Geoffrey Tyack, Sir James Pennethorne and the Making of Victorian London (Cambridge, 1992); Tristram Hunt, Building Jerusalem: The Rise and Fall of the Victorian City (Weidenfeld, 2004). The Grand Locarno Reception of the Foreign Office, recently restored. Following Palmerston's death in 1865 George Gilbert Scott added Gothic pointed vaults to his Classical design.

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston (1784-1865), c. 1855. Portrait by Francis Cruickshank (fl. 1848-81). Below: an impression of the Government Offices proposed by Sir James Pennethome (1801-71), seen from St James's Park. Bottom: the design by Charles Barry (1795-1860) for the Government Offices. Scott's original 'Gothic' design for the Foreign Office which came third in the 1857 competition. The Foreign Office, designed by George Gilbert Scott and built between 1861 and 1868, photographed from St James's Park, c. 1880. George Gilbert Scott, from the Illustrated London News, 1872. The exhibition of entries for the Government Offices competition in Westminster Hall, May 1857. From the Illustrated London News. ~~~~~~~~ By Bernard Porter Bernard Porter is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Newcastle and the author of The Battle of the Styles: Society, Culture and the Design of a New Foreign Office, 1855-61 (Continuum, 2011).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Nilangsu MitraDokument5 SeitenNilangsu MitraNilangsu MitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oundsource Heat Pump SystemsDokument442 SeitenOundsource Heat Pump SystemsЕвгений Врублевский90% (10)

- Chapter 7 Securing Information Systems AnswersDokument13 SeitenChapter 7 Securing Information Systems AnswersTanpopo Ikuta100% (1)

- LWIP port enables UDP data queries on CC2650Dokument10 SeitenLWIP port enables UDP data queries on CC2650Karthik KichuNoch keine Bewertungen

- At Mega 8535Dokument275 SeitenAt Mega 8535itmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Пръстени и коланиDokument80 SeitenПръстени и коланиУпражнения УП и АД Бакалавър 1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Essential Guide To Carrier Ethernet NetworksDokument64 SeitenEssential Guide To Carrier Ethernet NetworksGuillermo CarrascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Computer Network and Internet Lect 1 Part 1Dokument20 SeitenComputer Network and Internet Lect 1 Part 1Shakir HussainNoch keine Bewertungen

- 03-AHU Schedule 16-02-11Dokument23 Seiten03-AHU Schedule 16-02-11karunvandnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Published Paper 2019Dokument5 SeitenPublished Paper 2019Rizwan KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lenovo Z50-70 NM-A273 ACLUA - MB - 20131231 PDFDokument59 SeitenLenovo Z50-70 NM-A273 ACLUA - MB - 20131231 PDFSiriusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land DevelopmentDokument130 SeitenLand Developmentnirmal9583% (6)

- Windsor-Castle Case-StudyDokument25 SeitenWindsor-Castle Case-Studyapi-404658617Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adams 2017.1 Doc Product InformationDokument7 SeitenAdams 2017.1 Doc Product InformationGamze GülermanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case StudyDokument23 SeitenCase Studysatyam gupta100% (1)

- Estimating, Costing AND Valuation: by RangawalaDokument6 SeitenEstimating, Costing AND Valuation: by RangawalaDhrubajyoti Datta0% (2)

- Assessor - County Clerk - RecorderDokument2 SeitenAssessor - County Clerk - RecorderGeraldyneNoch keine Bewertungen

- IT 205 Chapter 1: Introduction to Integrative Programming and TechnologiesDokument42 SeitenIT 205 Chapter 1: Introduction to Integrative Programming and TechnologiesAaron Jude Pael100% (2)

- Standard Growth RoomsDokument8 SeitenStandard Growth Roomsapi-177042586Noch keine Bewertungen

- SPECIMEN EXAM TCC 102 AnswerDokument17 SeitenSPECIMEN EXAM TCC 102 Answerapi-26781128Noch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering Basis of NZS 3604 - Updated7 PDFDokument112 SeitenEngineering Basis of NZS 3604 - Updated7 PDFJeanette MillerNoch keine Bewertungen

- RCSE 2012 exam questionsDokument13 SeitenRCSE 2012 exam questionsAli Ahmad ButtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Limit State MethodDokument15 SeitenLimit State Methodvishal tomarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10-0 Software AG Infrastructure Administrators GuideDokument109 Seiten10-0 Software AG Infrastructure Administrators GuideishankuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2000 - The Role of Acoustics in SanctuariesDokument18 Seiten2000 - The Role of Acoustics in SanctuariesBoris RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Suikoden II Perfect Game Guide v2.1 - Neoseeker WalkthroughsDokument27 SeitenSuikoden II Perfect Game Guide v2.1 - Neoseeker WalkthroughsSMTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pos 140 03 Ig PDFDokument282 SeitenPos 140 03 Ig PDFanand.g7720Noch keine Bewertungen

- EdaDokument4 SeitenEdaJyotirmoy GuhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atmel 11209 32 Bit Cortex M4 Microcontroller SAM G51 DatasheetDokument866 SeitenAtmel 11209 32 Bit Cortex M4 Microcontroller SAM G51 Datasheetmsmith6477Noch keine Bewertungen